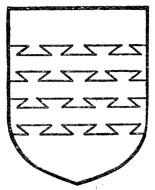

Fig. 60.—Arms of Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke: "Baruly argent and azure, an orle of martlets gules." (From his seal.)

With the exception of the chief, the quarter, the canton, the flaunch, and the bordure, an ordinary or sub-ordinary is always of greater importance, and therefore should be mentioned before any other charge, but in the cases alluded to the remainder of the shield is first blazoned, before attention is paid to these figures. Thus we should get: "Argent, a chevron between three mullets gules, on a chief of the last three crescents of the second;" or "Sable, a lion rampant between three fleurs-de-lis or, on a canton argent a mascle of the field;" or "Gules, two chevronels between three mullets pierced or, within a bordure engrailed argent charged with eight roses of the field." The arms in Fig. 61 are an interesting example of this point. They are those of John de Bretagne, Earl of Richmond (d. 1334), and would properly be blazoned: "Chequy or and azure, a bordure gules, charged with lions passant guardant or ('a bordure of England'), over all a canton (sometimes a quarter) ermine."

If two ordinaries or sub-ordinaries appear in the same field, certain discretion needs to be exercised, but the arms of Fitzwalter, for example, are as follows: "Or, a fess between two chevrons gules."

When charges are placed in a series following the direction of any ordinary they are said to be "in bend," "in chevron," or "in pale," as the case may be, and not only must their position on the shield as regards each other be specified, but their individual direction must also be noted.

A coat of arms in which three spears were placed side by side, but each erect, would be blazoned: "Gules, three tilting-spears palewise in fess;" but if the spears were placed horizontally, one above the other, they would be blazoned: "Three tilting-spears fesswise in pale," because in the latter case each spear is placed fesswise, but the three occupy in relation to each other the position of a pale. Three tilting-spears fesswise which were not in pale would be depicted 2 and 1.

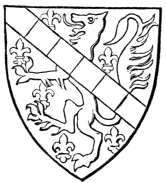

When one charge surmounts another, the undermost one is mentioned first, as in the arms of Beaumont (see Fig. 62). Here the lion rampant is the principal charge, and the bend which debruises it is consequently mentioned afterwards.

In the cases of a cross and of a saltire, the charges when all are alike would simply be described as between four objects, though the term "cantonned by" four objects is sometimes met with. If the objects are not the same, they must be specified as being in the 1st, 2nd, or 3rd quarters, if the ordinary be a cross. If it be a saltire, it will be found that in Scotland the charges are mentioned as being in chief and base, and in the "flanks." In England they would be described as being in pale and in fess if the alternative charges are the same; if not, they would be described as in chief, on the dexter side, on the sinister side, and in base.

Fig. 62.—Arms of John de Beaumont, Lord Beaumont (d. 1369): Azure, semé-de-lis and a lion rampant or, over all a bend gobony argent and gules. (From his seal.)

When a specified number of charges is immediately followed by the same number of charges elsewhere disposed, the number is not repeated, the words "as many" being substituted instead. Thus: "Argent, on a chevron between three roses gules, as many crescents of the field." When any charge, ordinary, or mark of cadency surmounts a single object, that object is termed "debruised" by that ordinary. If it surmounts everything, as, for instance, "a bendlet sinister," this would be termed "over all." When a coat of arms is "party" coloured in its field and the charges are alternately of the same colours transposed, the term counterchanged is used. For example, "Party per pale argent and sable, three chevronels between as many mullets pierced all counterchanged." In that case the coat is divided down the middle, the dexter field being argent, and the sinister sable; the charges on the sable being argent, whilst the charges on the argent are sable. A mark of cadency is mentioned last, and is termed "for difference"; a mark of bastardy, or a mark denoting lack of blood descent, is termed "for distinction."

Certain practical hints, which, however, can hardly be termed rules, were suggested by the late Mr. J. Gough Nicholls in 1863, when writing in the Herald and Genealogist, and subsequent practice has since conformed therewith, though it may be pointed out with advantage that these suggestions are practically, and to all intents and purposes, the same rules which have been observed officially over a long period. Amongst these suggestions he advises that the blazoning of every coat or quarter should begin with a capital letter, and that, save on the occurrence of proper names, no other capitals should be employed. He also suggests that punctuation marks should be avoided as much as possible, his own practice being to limit the use of the comma to its occurrence after each tincture. He suggests also that figures should be omitted in all cases except in the numbering of quarterings.

When one or more quarterings occur, each is treated separately on its own merits and blazoned entirely without reference to any other quartering.

Fig. 63.—A to B, the chief; C to D, the base; A to C, dexter side; B to D, sinister side. A, dexter chief; B, sinister chief; C, dexter base; D, sinister base. 1, 2, 3, chief; 7, 8, 9, base; 2, 5, 8, pale; 4, 5, 6, fess; 5, fess point.

In blazoning a coat in which some quarterings (grand quarterings) are composed of several coats placed sub-quarterly, sufficient distinction is afforded for English purposes of writing or printing if Roman numerals are employed to indicate the grand quarters, and Arabic figures the sub-quarters. But in speaking such a method would need to be somewhat modified in accordance with the Scottish practice, which describes grand quarterings as such, and so alludes to them.

The extensive use of bordures, charged and uncharged, in Scotland, which figure sometimes round the sub-quarters, sometimes round the grand quarters, and sometimes round the entire escutcheon, causes so much confusion that for the purposes of blazoning it is essential that the difference between quarters and grand quarters should be clearly defined.

In order to simplify the blazoning of a shield, and so express the position of the charges, the field has been divided into points, of which those placed near the top, and to the dexter, are always considered the more important. In heraldry, dexter and sinister are determined, not from the point of view of the onlooker, but from that of the bearer of the shield. The diagram (Fig. 63) will serve to explain the plan of a shield's surface.

If a second shield be placed upon the fess point, this is called an inescutcheon (in German, the "heart-shield"). The enriching of the shield with an inescutcheon came into lively use in Germany in the course of the latter half of the fifteenth century. Later on, further points of honour were added, as the honour point (a, Fig. 64), and the nombril point (b, Fig. 64). These extra shields laid upon the others should correspond as much as possible in shape to the chief shield. If between the inescutcheon and the chief shield still another be inserted, it is called the "middle shield," from its position, but except in Anglicised versions of Continental arms, these distinctions are quite foreign to British armory.

In conclusion, it may be stated that although the foregoing are the rules which are usually observed, and that every effort should be made to avoid unnecessary tautology, and to make the blazon as brief as possible, it is by no manner of means considered officially, or unofficially, that any one of these rules is so unchangeable that in actual practice it cannot be modified if it should seem advisable so to do. For the essential necessity of accuracy is of far greater importance than any desire to be brief, or to avoid tautology. This should be borne in mind, and also the fact that in official practice no such hide-bound character is given to these rules, as one is led to believe is the case when perusing some of the ordinary text-books of armory. They certainly are not laws, they are hardly "rules," perhaps being better described as accepted methods of blazoning.

CHAPTER IX

THE SO-CALLED ORDINARIES AND SUB-ORDINARIES

Arms, and the charges upon arms, have been divided into many fantastical divisions. There is a type of the precise mind much evident in the scientific writing of the last and the preceding centuries which is for ever unhappy unless it can be dividing the object of its consideration into classes and divisions, into sub-classes and sub-divisions. Heraldry has suffered in this way; for, oblivious of the fact that the rules enunciated are impossible as rigid guides for general observance, and that they never have been complied with, and that they never will be, a "tabular" system has been evolved for heraldry as for most other sciences. The "precise" mind has applied a system obviously derived from natural history classification to the principles of armory. It has selected a certain number of charges, and has been pleased to term them ordinaries. It has selected others which it has been pleased to term sub-ordinaries. The selection has been purely arbitrary, at the pleasure of the writer, and few writers have agreed in their classifications. One of the foremost rules which former heraldic writers have laid down is that an ordinary must contain the third part of the field. Now it is doubtful whether an ordinary has ever been drawn containing the third part of the field by rigid measurement, except in the solitary instance of the pale, when it is drawn "per fess counterchanged," for the obvious purpose of dividing the shield into six equal portions, a practice which has been lately pursued very extensively owing to the ease with which, by its adoption, a new coat of arms can be designed bearing a distinct resemblance to one formerly in use without infringing the rights of the latter. Certainly, if the ordinary is the solitary charge upon the shield, it will be drawn about that specified proportion. But when an attempt is made to draw the Walpole coat (which cannot be said to be a modern one) so that it shall exhibit three ordinaries, to wit, one fess and two chevrons (which being interpreted as three-thirds of the shield, would fill it entirely), and yet leave a goodly proportion of the field still visible, the absurdity is apparent. And a very large proportion of the classification and rules which occupy such a large proportion of the space in the majority of heraldic text-books are equally unnecessary, confusing, and incorrect, and what is very much more important, such rules have never been recognised by the powers that have had the control of armory from the beginning of that control down to the present day. I shall not be surprised to find that many of my critics, bearing in mind how strenuously I have pleaded elsewhere for a right and proper observance of the laws of armory, may think that the foregoing has largely the nature of a recantation. It is nothing of the kind, and I advocate as strenuously as I have ever done, the compliance with and the observance of every rule which can be shown to exist. But this is no argument whatever for the idle invention of rules which never have existed; or for the recognition of rules which have no other origin than the imagination of heraldic writers. Nor is it an argument for the deduction of unnecessary regulations from cases which can be shown to have been exceptions. Too little recognition is paid to the fact that in armory there are almost as many rules of exception as original rules. There are vastly more plain exceptions to the rules which should govern them.

On the subject of ordinaries, I cannot see wherein lies the difference between a bend and a lion rampant, save their difference in form, yet the one is said to be an ordinary, the other is merely a charge. Each has its special rules to be observed, and whilst a bend can be engrailed or invected, a lion can be guardant or regardant; and whilst the one can be placed between two objects, which objects will occupy a specified position, so can the other. Each can be charged, and each furnishes an excellent example of the futility of some of the ancient rules which have been coined concerning them. The ancient rules allow of but one lion and one bend upon a shield, requiring that two bends shall become bendlets, and two lions lioncels, whereas the instance we have already quoted—the coat of Walpole—has never been drawn in such form that either of the chevrons could have been considered chevronels, and it is rather late in the day to degrade the lions of England into unblooded whelps. To my mind the ordinaries and sub-ordinaries are no more than first charges, and though the bend, the fess, the pale, the pile, the chevron, the cross, and the saltire will always be found described as honourable ordinaries, whilst the chief seems also to be pretty universally considered as one of the honourable ordinaries, such hopeless confusion remains as to the others (scarcely any two writers giving similar classifications), that the utter absurdity of the necessity for any classification at all is amply demonstrated. Classification is only necessary or desirable when a certain set of rules can be applied identically to all the set of figures in that particular class. Even this will not hold with the ordinaries which have been quoted.

A pale embattled is embattled upon both its edges; a fess embattled is embattled only upon the upper edge; a chief is embattled necessarily only upon the lower; and the grave difficulty of distinguishing "per pale engrailed" from "per pale invected" shows that no rigid rules can be laid down. When we come to sub-ordinaries, the confusion is still more apparent, for as far as I can see the only reason for the classification is the tabulating of rules concerning the lines of partition. The bordure and the orle can be, and often are, engrailed or embattled; the fret, the lozenge, the fusil, the mascle, the rustre, the flanche, the roundel, the billet, the label, the pairle, it would be practically impossible to meddle with; and all these figures have at some time or another, and by some writer or other, been included amongst either the ordinaries or the sub-ordinaries. In fact there is no one quality which these charges possess in common which is not equally possessed by scores of other well-known charges, and there is no particular reason why a certain set should be selected and dignified by the name of ordinaries; nor are there any rules relating to ordinaries which require the selection of a certain number of figures, or of any figures to be controlled by those rules, with one exception. The exception is to be found not in the rules governing the ordinaries, but in the rules of blazon. After the field has been specified, the principal charge must be mentioned first, and no charge can take precedence of a bend, fess, pale, pile, chevron, cross, or saltire, except one of themselves. If there be any reason for a subdivision those charges must stand by themselves, and might be termed the honourable ordinaries, but I can see no reason for treating the chief, the quarter, the canton, gyron, flanche, label, orle, tressure, fret, inescutcheon, chaplet, bordure, lozenge, fusil, mascle, rustre, roundel, billet, label, shakefork, and pairle, as other than ordinary charges. They certainly are purely heraldic, and each has its own special rules, but so in heraldry have the lion, griffin, and deer. Here is the complete list of the so-called ordinaries and sub-ordinaries: The bend; fess; bar; chief; pale; chevron; cross; saltire; pile; pairle, shakefork or pall; quarter; canton; gyron; bordure; orle; tressure; flanche; label, fret; inescutcheon; chaplet; lozenge; fusil; mascle; rustre; roundel; billet, together with the diminutives of such of these as are in use.

With reference to the origin of these ordinaries, by the use of which term is meant for the moment the rectilinear figures peculiar to armory, it may be worth the passing mention that the said origin is a matter of some mystery. Guillim and the old writers almost universally take them to be derived from the actual military scarf or a representation of it placed across the shield in various forms. Other writers, taking the surcoat and its decoration as the real origin of coats of arms, derive the ordinaries from the belt, scarf, and other articles of raiment. Planché, on the other hand, scouted such a derivation, putting forward upon very good and plausible grounds the simple argument that the origin of the ordinaries is to be found in the cross-pieces of wood placed across a shield for strengthening purposes. He instances cases in which shields, apparently charged with ordinaries but really strengthened with cross-pieces, can be taken back to a period long anterior to the existence of regularised armory. But then, on the other hand, shields can be found decorated with animals at an equally early or even an earlier period, and I am inclined myself to push Planché's own argument even farther than he himself took it, and assert unequivocally that the ordinaries had in themselves no particular symbolism and no definable origin whatever beyond that easy method of making some pattern upon a shield which was to be gained by using straight lines. That they ever had any military meaning, I cannot see the slightest foundation to believe; their suggested and asserted symbolism I totally deny. But when we can find, as Planché did, that shields were strengthened with cross-pieces in various directions, it is quite natural to suppose that these cross-pieces afforded a ready means of decoration in colour, and this would lead a good deal of other decoration to follow similar forms, even in the absence of cross-pieces upon the definite shield itself. The one curious point which rather seems to tell against Planché's theory is that in the earliest "rolls" of arms but a comparatively small proportion of the arms are found to consist of these rectilinear figures, and if the ordinaries really originated in strengthening cross-pieces one would have expected a larger number of such coats of arms to be found; but at the same time such arms would, in many cases, in themselves be so palpably mere meaningless decoration of cross-pieces upon plain shields, that the resulting design would not carry with it such a compulsory remembrance as would a design, for example, derived from lines which had plainly had no connection with the construction of the shield. Nor could it have any such basis of continuity. Whilst a son would naturally paint a lion upon his shield if his father had done the same, there certainly would not be a similar inducement for a son to follow his father's example where the design upon a shield were no more than different-coloured strengthening pieces, because if these were gilt, for example, the son would naturally be no more inclined to perpetuate a particular form of strengthening for his shield, which might not need it, than any particular artistic division with which it was involved, so that the absence of arms composed of ordinaries from the early rolls of arms may not amount to so very much. Still further, it may well be concluded that the compilers of early rolls of arms, or the collectors of the details from which early rolls were made at a later date, may have been tempted to ignore, and may have been justified in discarding from their lists of arms, those patterns and designs which palpably were then no more than a meaningless colouring of the strengthening pieces, but which patterns and designs by subsequent continuous usage and perpetuation became accepted later by certain families as the "arms" their ancestors had worn. It is easy to see that such meaningless patterns would have less chance of survival by continuity of usage, and at the same time would require a longer continuity of usage, before attaining to fixity as a definite design.

The undoubted symbolism of the cross in so many early coats of arms has been urged strongly by those who argue either for a symbolism for all these rectilinear figures or for an origin in articles of dress. But the figure of the cross preceded Christianity and organised armory, and it had an obvious decorative value which existed before, and which exists now outside any attribute it may have of a symbolical nature. That it is an utterly fallacious argument must be admitted when it is remembered that two lines at right angles make a cross—probably the earliest of all forms of decoration—and that the cross existed before its symbolism. Herein it differs from other forms of decoration (e.g. the Masonic emblems) which cannot be traced beyond their symbolical existence. The cross, like the other heraldic rectilinear figures, came into existence, meaningless as a decoration for a shield, before armory as such existed, and probably before Christianity began. Then being in existence the Crusading instinct doubtless caused its frequent selection with an added symbolical meaning. But the argument can truthfully be pushed no farther.

THE BEND

The bend is a broad band going from the dexter chief corner to the sinister base (Fig. 65). According to the old theorists this should contain the third part of the field. As a matter of fact it hardly ever does, and seldom did even in the oldest examples. Great latitude is allowed to the artist on this point, in accordance with whether the bend be plain or charged, and more particularly according to the charges which accompany it in the shield and their disposition thereupon.

"Azure, a bend or," is the well-known coat concerning which the historic controversy was waged between Scrope and Grosvenor. As every one knows, it was finally adjudged to belong to the former, and a right to it has also been proved by the Cornish family of Carminow.

A bend is, of course, subject to the usual variations of the lines of partition (Figs. 66-75).

A bend compony (Fig. 76), will be found in the arms of Beaumont, and the difference between this (in which the panes run with the bend) and a bend barry (in which the panes are horizontal, Fig. 77), as in the arms of King,[7] should be noticed.

A bend wavy is not very usual, but will be found in the arms of Wallop, De Burton, and Conder. A bend raguly appears in the arms of Strangman.

When a bend and a bordure appear upon the same arms, the bend is not continued over the bordure, and similarly it does not surmount a tressure (Fig. 78), but stops within it.

A bend upon a bend is by no means unusual. An example of this will be found in a coat of Waller. Cases where this happens need to be carefully scrutinised to avoid error in blazoning.

A bend lozengy, or of lozenges (Fig. 79), will be found in the arms of Bolding.

A bend flory and counterflory will be found in the arms of Fellows, a quartering of Tweedy.

A bend chequy will be found in the arms of Menteith, and it should be noticed that the checks run the way of the bend.

Ermine spots upon a bend are represented the way of the bend.

Occasionally two bends will be found, as in the arms of Lever: Argent, two bends sable, the upper one engrailed (vide Lyon Register—escutcheon of pretence on the arms of Goldie-Scot of Craigmore, 1868); or as in the arms of James Ford, of Montrose, 1804: Gules, two bends vairé argent and sable, on a chief or, a greyhound courant sable between two towers gules. A different form appears in the arms of Zorke or Yorke (see Papworth), which are blazoned: Azure, a bend argent, impaling argent, a bend azure. A solitary instance of three bends (which, however, effectually proves that a bend cannot occupy the third part of the field) occurs in the arms of Penrose, matriculated in Lyon Register in 1795 as a quartering of Cumming-Gordon of Altyre. These arms of Penrose are: Argent, three bends sable, each charged with as many roses of the field.

A charge half the width of a bend is a bendlet (Fig. 80), and one half the width of a bendlet is a cottise (Fig. 81), but a cottise cannot exist alone, inasmuch as it has of itself neither direction nor position, but is only found accompanying one of the ordinaries. The arms of Harley are an example of a bend cottised.

Bendlets will very seldom be found either in addition to a bend, or charged, but the arms of Vaile show both these peculiarities.

A bend will usually be found between two charges. Occasionally it will be found between four, but more frequently between six. In none of these cases is it necessary to specify the position of the subsidiary charges. It is presumed that the bend separates them into even numbers, but their exact position (beyond this) upon the shield is left to the judgment of the artist, and their disposition is governed by the space left available by the shape of the shield. A further presumption is permitted in the case of a bend between three objects, which are presumed to be two in chief and one in base. But even in the case of three the position will be usually found to be specifically stated, as would be the case with any other uneven number.

Charges on a bend are placed in the direction of the bend. In such cases it is not necessary to specify that the charges are bendwise. When a charge or charges occupy the position which a bend would, they are said to be placed "in bend." This is not the same thing as a charge placed "bendwise" (or bendways). In this case the charge itself is slanted into the angle at which the bend crosses the shield, but the position of the charge upon the shield is not governed thereby.

When a bend and chief occur together in the same arms, the chief will usually surmount the bend, the latter issuing from the angle between the base of the chief and the side of the shield. An instance to the contrary, however, will be found in the arms of Fitz-Herbert of Swynnerton, in which the bend is continued over the chief. This instance, however (as doubtless all others of the kind), is due to the use of the bend in early times as a mark of difference. The coat of arms, therefore, had an earlier and separate existence without the bend, which has been superimposed as a difference upon a previously existing coat. The use of the bend as a difference will be again referred to when considering more fully the marks and methods of indicating cadency.

A curious instance of the use of the sun's rays in bend will be found in the arms of Warde-Aldam.[8]

The bend sinister (Fig. 82), is very frequently stated to be the mark of illegitimacy. It certainly has been so used upon some occasions, but these occasions are very few and far between, the charge more frequently made use of being the bendlet or its derivative the baton (Fig. 83). These will be treated more fully in the chapter on the marks of illegitimacy. The bend sinister, which is a band running from the sinister chief corner through the centre of the escutcheon to the dexter base, need not necessarily indicate bastardy. Naturally the popular idea which has originated and become stereotyped concerning it renders its appearance extremely rare, but in at least two cases it occurs without, as far as I am aware, carrying any such meaning. At any rate, in neither case are the coats "bastardised" versions of older arms. These cases are the arms of Shiffner: "Azure, a bend sinister, in chief two estoiles, in like bend or; in base the end and stock of an anchor gold, issuing from waves of the sea proper;" and Burne-Jones: "Azure, on a bend sinister argent, between seven mullets, four in chief and three in base or, three pairs of wings addorsed purpure."

No coat with the chief charge a single bendlet occurs in Papworth. A single case, however, is to be found in the Lyon Register in the duly matriculated arms of Porterfield of that Ilk: "Or, a bendlet between a stag's head erased in chief and a hunting-horn in base sable, garnished gules." Single bendlets, however, both dexter and sinister, occur as ancient difference marks, and are then sometimes known as ribands. So described, it occurs in blazon of the arms of Abernethy: "Or, a lion rampant gules, debruised of a ribbon sable," quartered by Lindsay, Earl of Crawford and Balcarres; but here again the bendlet is a mark of cadency. In the Gelre Armorial, in this particular coat the ribbon is made "engrailed," which is most unusual, and which does not appear to be the accepted form. In many of the Scottish matriculations of this Abernethy coat in which this riband occurs it is termed a "cost," doubtless another form of the word cottise.

When a bend or bendlets (or, in fact, any other charge) are raised above their natural position in the shield they are termed "enhanced" (Fig. 84). An instance of this occurs in the well-known coat of Byron, viz.: "Argent, three bendlets enhanced gules," and in the arms of Manchester, which were based upon this coat.

When the field is composed of an even number of equal pieces divided by lines following the angle of a bend the field is blazoned "bendy" of so many (Fig. 58). In most cases it will be composed of six or eight pieces, but as there is no diminutive of "bendy," the number must always be stated.

THE PALE

The pale is a broad perpendicular band passing from the top of the escutcheon to the bottom (Fig. 85). Like all the other ordinaries, it is stated to contain the third part of the area of the field, and it is the only one which is at all frequently drawn in that proportion. But even with the pale, the most frequent occasion upon which this proportion is definitely given, this exaggerated width will be presently explained. The artistic latitude, however, permits the pale to be drawn of this proportion if this be convenient to the charges upon it.

Like the other ordinaries, the pale will be found varied by the different lines of partition (Figs. 86-94).

The single circumstance in which the pale is regularly drawn to contain a full third of the field by measurement is when the coat is "per fess and a pale counterchanged." This, it will be noticed, divides the shield into six equal portions (Fig. 95). The ease with which, by the employment of these conditions, a new coat can be based upon an old one which shall leave three original charges in the same position, and upon a field of the original tincture, and yet shall produce an entirely different and distinct coat of arms, has led to this particular form being constantly repeated in modern grants.

The diminutive of the pale is the pallet (Fig. 96), and the pale cottised is sometimes termed "endorsed."

Except when it is used as a mark of difference or distinction (then usually wavy), the pallet is not found singly; but two pallets, or three, are not exceptional. Charged upon other ordinaries, particularly on the chief and the chevron, pallets are of constant occurrence.

When the field is striped vertically it is said to be "paly" of so many (Fig. 57).

The arms shown in Fig. 97 are interesting inasmuch as they are doubtless an early form of the coat per pale indented argent and gules, which is generally described as a banner borne for the honour of Hinckley, by the Simons de Montfort, Earls of Leicester, father and son. In a Roll temp. Henry III., to Simon the younger is ascribed "Le Banner party endentee dargent & de goules," although the arms of both father and son are known to have been as Fig. 98: "Gules, a lion rampant queue-fourchée argent." More probably the indented coat gives the original Montfort arms.

THE FESS

The fess is a broad horizontal band crossing the escutcheon in the centre (Fig. 99). It is seldom drawn to contain a full third of the area of the shield. It is subject to the lines of partition (Figs. 100-109).

A curious variety of the fess dancetté is borne by the Shropshire family Plowden of Plowden. They bear: Azure, a fess dancetté, the upper points terminating in fleurs-de-lis (Fig. 110). A fess couped (Fig. 111) is found in the arms of Lee.

The "fess embattled" is only crenellated upon the upper edge; but when both edges are embattled it is a fess embattled and counter-embattled. The term bretessé (which is said to indicate that the battlements on the upper edge are opposite the battlements on the lower edge, and the indentations likewise corresponding) is a term and a distinction neither of which are regarded in British armory.

A fess wreathed (Fig. 112) is a bearing which seems to be almost peculiar to the Carmichael family, but the arms of Waye of Devon are an additional example, being: Sable, two bars wreathed argent and gules. I know of no other ordinary borne in a wreathed form, but there seems no reason why this peculiarity should be confined to the fess.

It is a fixed rule of British armory that there can be only one fess upon a shield. If two figures of this character are found they are termed bars (Fig. 113). But it is hardly correct to speak of the bar as a diminutive of the fess, because if two bars only appear on the shield there would be little, if any, diminution made from the width of the fess when depicting the bars. As is the case with other ordinaries, there is much latitude allowed to the artist in deciding the dimensions, it being usually permitted for these to be governed by the charges upon the fess or bars, and the charges between which these are placed.

Bars, like the fess, are of course equally subject to all the varying lines of partition (Figs. 114-118).

The diminutive of the bar is the barrulet, which is half its width and double the width of the cottise. But the barrulet will almost invariably be found borne in pairs, when such a pair is usually known as a "bar gemel" and not as two barrulets. Thus a coat with four barrulets would have these placed at equal distances from each other; but a coat with two bars gemel would be depicted with two of its barrulets placed closely together in chief and two placed closely together in base, the disposition being governed by the fact that the two barrulets comprising the "bar gemel" are only one charge. Fig. 119 shows three bars gemel. There is theoretically no limit to the number of bars or bars gemel which can be placed upon the shield. In practical use, however, four will be found the maximum.

A field composed of four, six, eight, or ten horizontal pieces of equal width is "barry of such and such a number of pieces," the number being always specified (Figs. 55 and 56). A field composed of an equal number of horizontally shaped pieces, when these exceed ten in number, is termed "barruly" of such and such a number. The term barruly is also sometimes used for ten pieces. If the number is omitted "barry" will usually be of six pieces, though sometimes of eight. On the other hand a field composed of five, seven, or nine pieces is not barry, but (e.g.) two bars, three bars, and four bars respectively. This distinction in modern coats needs to be carefully noted, but in ancient coats it is not of equal importance. Anciently also a shield "barry" was drawn of a greater number of pieces (see Figs. 120, 121 and 122) than would nowadays be employed. In modern armory a field so depicted would more correctly be termed "barruly."

Whilst a field can be and often is barry of two colours or two metals, an uneven number of pieces must of necessity be of metal and colour or fur. Consequently in a shield e.g. divided into seven equal horizontal divisions, alternately gules and sable, there must be a mistake somewhere.

Although these distinctions require to be carefully noted as regards modern arms, it should be remembered that they are distinctions evolved by the intricacies and requirements of modern armory, and ancient arms were not so trammelled.

A field divided horizontally into three equal divisions of e.g. gules, sable, and argent is theoretically blazoned by British rules "party per fess gules and argent, a fess sable." This, however, gives an exaggerated width to the fess which it does not really possess with us, and the German rules, which would blazon it "tierced per fess gules, sable, and argent," would seem preferable.

A field which is barry may also be counterchanged, as in the arms of Ballingall, where it is counterchanged per pale; but it can also be counterchanged per chevron (Fig. 123), or per bend dexter or sinister. Such counterchanging should be carefully distinguished from fields which are "barry-bendy" (Fig. 124), or "paly-bendy" (Fig. 125). In these latter cases the field is divided first by lines horizontal (for barry) or perpendicular (for paly), and subsequently by lines bendy (dexter or sinister).

The result produced is very similar to "lozengy" (Fig. 126), and care should be taken to distinguish the two.

Barry-bendy is sometimes blazoned "fusilly in bend," whilst paly-bendy is sometimes blazoned "fusilly in bend sinister," but the other terms are the more accurate and acceptable.