"Lozengy" is made by use of lines in bend crossed by lines in bend sinister (Fig. 126), and "fusilly" the same, only drawn at a more acute angle.

THE CHEVRON

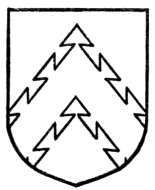

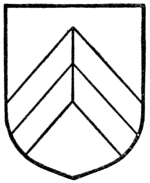

Probably the ordinary of most frequent occurrence in British, as also in French armory, is the chevron (Fig. 127). It is comparatively rare in German heraldry. The term is derived from the French word chevron, meaning a rafter, and the heraldic chevron is the same shape as a gable rafter. In early examples of heraldic art the chevron will be found depicted reaching very nearly to the top of the shield, the angle contained within the chevron being necessarily more acute. The chevron then attained very much more nearly to its full area of one-third of the field than is now given to it. As the chevron became accompanied by charges, it was naturally drawn so that it would allow of these charges being more easily represented, and its height became less whilst the angle it enclosed was increased. But now, as then, it is perfectly at the pleasure of the artist to design his chevron at the height and angle which will best allow the proper representation of the charges which accompany it.

The chevron, of course, is subject to the usual lines of partition (Figs. 128-136), and can be cottised and doubly cottised (Fig. 137).

It is usually found between three charges, but the necessity of modern differentiation has recently introduced the disposition of four charges, three in chief and one in base, which is by no means a happy invention. An even worse disposition occurs in the arms of a certain family of Mitchell, where the four escallops which are the principal charges are arranged two in chief and two in base.

Ermine spots upon a chevron do not follow the direction of it, but in the cases of chevrons vair, and chevrons chequy, authoritative examples can be found in which the chequers and rows of vair both do, and do not, conform to the direction of the chevron. My own preference is to make the rows horizontal.

A chevron quarterly is divided by a line chevronwise, apparently dividing the chevron into two chevronels, and then by a vertical line in the centre (Fig. 138).

A chevron in point embowed will be found in the arms of Trapaud quartered by Adlercron (Fig. 139).

A field per chevron (Fig. 52) is often met with, and the division line in this case (like the enclosing lines of a real chevron) is subject to the usual partition lines, but how one is to determine the differentiation between per chevron engrailed and per chevron invecked I am uncertain, but think the points should be upwards for engrailed.

The field when entirely composed of an even number of chevrons is termed "chevronny" (Fig. 59).

The diminutive of the chevron is the chevronel (Fig. 140).

Chevronels "interlaced" or "braced" (Fig. 141), will be found in the arms of Sirr. The chevronel is very seldom met with singly, but a case of this will be found in the arms of Spry.

A chevron "rompu" or broken is depicted as in Fig. 142.

Fig. 139.—Armorial bearings of Rodolph Ladeveze Adlercron, Esq.: Quarterly, 1 and 4, argent, an eagle displayed, wings inverted sable, langued gules, membered and ducally crowned or (for Adlercron): 2 and 3, argent, a chevron in point embowed between in chief two mullets and in base a lion rampant all gules (for Trapaud). Mantling sable and argent. Crest: on a wreath of the colours, a demi-eagle displayed sable, langued gules, ducally crowned or, the dexter wing per fess argent and azure, the sinister per fess of the last and or. Motto: "Quo fata vocant."

THE PILE

The pile (Fig. 143) is a triangular wedge usually (and unless otherwise specified) issuing from the chief. The pile is subject to the usual lines of partition (Figs. 144-151).

The early representation of the pile (when coats of arms had no secondary charges and were nice and simple) made the point nearly reach to the base of the escutcheon, and as a consequence it naturally was not so wide. It is now usually drawn so that its upper edge occupies very nearly the whole of the top line of the escutcheon; but the angles and proportions of the pile are very much at the discretion of the artist, and governed by the charges which need to be introduced in the field of the escutcheon or upon the pile.

A single pile may issue from any point of the escutcheon except the base; the arms of Darbishire showing a pile issuing from the dexter chief point.

A single pile cannot issue in base if it be unaccompanied by other piles, as the field would then be blazoned per chevron.

Two piles issuing in chief will be found in the arms of Holles, Earl of Clare.

When three piles, instead of pointing directly at right angles to the line of the chief, all point to the same point, touching or nearly touching at the tips, as in the arms of the Earl of Huntingdon and Chester or in the arms of Isham,[9] they are described as three piles in point. This term and its differentiation probably are modern refinements, as with the early long-pointed shield any other position was impossible. The arms of Henderson show three piles issuing from the sinister side of the escutcheon.

A disposition of three piles which will very frequently be found in modern British heraldry is two issuing in chief and one in base (Fig. 152).

Piles terminating in fleurs-de-lis or crosses patée are to be met with, and reference may be made to the arms of Poynter and Dickson-Poynder. Each of these coats has the field pily counter-pily, the points ending in crosses formée.

An unusual instance of a pile in which it issues from a chevron will be found in the arms of Wright, which are: "Sable, on a chevron argent, three spear-heads gules, in chief two unicorns' heads erased argent, armed and maned or, in base on a pile of the last, issuant from the chevron, a unicorn's head erased of the field."

THE SHAKEFORK

The pall, pairle, or shakefork (Fig. 153), is almost unknown in English heraldry, but in Scotland its constant occurrence in the arms of the Cunninghame and allied families has given it a recognised position among the ordinaries.

As usually borne by the Cunninghame family the ends are couped and pointed, but in some cases it is borne throughout.

The pall in its proper ecclesiastical form appears in the arms of the Archiepiscopal Sees of Canterbury, Armagh, and Dublin. Though in these cases the pall or pallium (Fig. 154), is now considered to have no other heraldic status than that of an appropriately ecclesiastical charge upon an official coat of arms, there can be very little doubt that originally the pall of itself was the heraldic symbol in this country of an archbishop, and borne for that reason by all archbishops, including the Archbishop of York, although his official archiepiscopal coat is now changed to: "Gules, two keys in saltire argent, in chief a royal crown or."

The necessity of displaying this device of rank—the pallium—upon a field of some tincture has led to its corruption into a usual and stereotyped "charge."

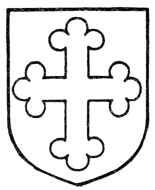

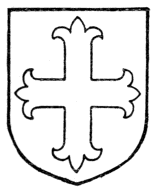

THE CROSS

The heraldic cross (Fig. 155), the huge preponderance of which in armory we of course owe to the Crusades, like all other armorial charges, has strangely developed. There are nearly four hundred varieties known to armory, or rather to heraldic text-books, and doubtless authenticated examples could be found of most if not of them all. But some dozen or twenty forms are about as many as will be found regularly or constantly occurring. Some but not all of the varieties of the cross are subject to the lines of partition (Figs. 156-161).

When the heraldic cross was first assumed with any reason beyond geometrical convenience, there can be no doubt that it was intended to represent the Sacred Cross itself. The symbolism of the cross is older than our present system of armory, but the cross itself is more ancient than its symbolism. A cross depicted upon the long, pointed shields of those who fought for the Cross would be of that shape, with the elongated arm in base.

But the contemporary shortening of the shield, together with the introduction of charges in its angles, led naturally to the arms of the cross being so disposed that the parts of the field left visible were as nearly as possible equal. The Sacred Cross, therefore, in heraldry is now known as a "Passion Cross" (Fig. 162) (or sometimes as a "long cross"), or, if upon steps or "grieces," the number of which needs to be specified, as a "Cross Calvary" (Fig. 163). The crucifix (Fig. 164), under that description is sometimes met with as a charge.

The ordinary heraldic cross (Fig. 155) is always continued throughout the shield unless stated to be couped (Fig. 165).

Of the crosses more regularly in use may be mentioned the cross botonny (Fig. 166), the cross flory (Fig. 167), which must be distinguished from the cross fleuretté (Fig. 168); the cross moline, (Fig. 169), the cross potent (Fig. 170), the cross patée or formée (Fig. 171), the cross patonce (Fig. 172), and the cross crosslet (Fig. 173).

PLATE III.

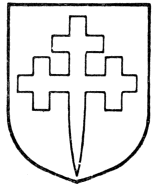

Of other but much more uncommon varieties examples will be found of the cross parted and fretty (Fig. 174), of the cross patée quadrate (Fig. 175), of a cross pointed and voided in the arms of Dukinfield (quartered by Darbishire), and of a cross cleché voided and pometté as in the arms of Cawston. A cross quarter-pierced (Fig. 176) has the field visible at the centre. A cross tau or St. Anthony's Cross is shown in Fig. 177, the real Maltese Cross in Fig. 178, and the Patriarchal Cross in Fig. 179.

Whenever a cross or cross crosslet has the bottom arm elongated and pointed it is said to be "fitched" (Figs. 180 and 181), but when a point is added at the foot e.g. of a cross patée, it is then termed "fitchée at the foot" (Fig. 182).

Of the hundreds of other varieties it may confidently be said that a large proportion originated in misunderstandings of the crude drawings of early armorists, added to the varying and alternating descriptions applied at a more pliable and fluent period of heraldic blazon. A striking illustration of this will be found in the cross botonny, which is now, and has been for a long time past, regularised with us as a distinct variety of constant occurrence. From early illustrations there is now no doubt that this was the original form, or one of the earliest forms, of the cross crosslet. It is foolish to ignore these varieties, reducing all crosses to a few original forms, for they are now mostly stereotyped and accepted; but at the same time it is useless to attempt to learn them, for in a lifetime they will mostly be met with but once each or thereabouts. A field semé of cross crosslets (Fig. 183) is termed crusilly.

THE SALTIRE

The saltire or saltier (Fig. 184) is more frequently to be met with in Scottish than in English heraldry. This is not surprising, inasmuch as the saltire is known as the Cross of St. Andrew, the Patron Saint of Scotland. Its form is too well known to need description. It is of course subject to the usual partition lines (Figs. 185-192).

When a saltire is charged the charges are usually placed conformably therewith.

The field of a coat of arms is often per saltire.

When one saltire couped is the principal charge it will usually be found that it is couped conformably to the outline of the shield; but if the couped saltire be one of a number or a subsidiary charge it will be found couped by horizontal lines, or by lines at right angles. The saltire has not developed into so many varieties of form as the cross, and (e.g.) a saltire botonny is assumed to be a cross botonny placed saltireways, but a saltire parted and fretty is to be met with (Fig. 193).

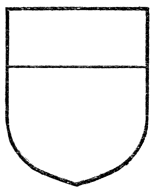

THE CHIEF

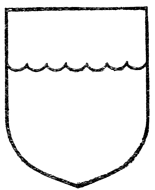

The chief (Fig. 194), which is a broad band across the top of the shield containing (theoretically, but not in fact) the uppermost third of the area of the field, is a very favourite ordinary. It is of course subject to the variations of the usual partition lines (Figs. 195-203). It is usually drawn to contain about one-fifth of the area of the field, though in cases where it is used for a landscape augmentation it will usually be found of a rather greater area.

The chief especially lent itself to the purposes of honourable augmentation, and is constantly found so employed. As such it will be referred to in the chapter upon augmentations, but a chief of this character may perhaps be here referred to with advantage, as this will indicate the greater area often given to it under these conditions, as in the arms of Ross-of-Bladensburg (Plate II.).

Knights of the old Order of St. John of Jerusalem and also of the modern Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem in England display above their personal arms a chief of the order, but this will be dealt with more fully in the chapter relating to the insignia of knighthood.

Save in exceptional circumstances, the chief is never debruised or surmounted by any ordinary.

The chief is ordinarily superimposed over the tressure and over the bordure, partly defacing them by the elimination of the upper part thereof. This happens with the bordure when it is a part of the original coat of arms. If, however, the chief were in existence at an earlier period and the bordure is added later as a mark of difference, the bordure surrounds the chief. On the other hand, if a bordure exists, even as a mark of difference, and a chief of augmentation is subsequently added, or a canton for distinction, the chief or the canton in these cases would surmount the bordure.

Similarly a bend when added later as a mark of difference surmounts the chief. Such a case is very unusual, as the use of the bend for differencing has long been obsolete.

A chief is never couped or cottised, and it has no diminutive in British armory.

THE QUARTER

The quarter is not often met with in English armory, the best-known instance being the well-known coat of Shirley, Earl Ferrers, viz: Paly of six or and azure, a quarter ermine. The arms of the Earls of Richmond (Fig. 204) supply another instance. Of course as a division of the field under the blazon of "quarterly" (e.g. or and azure) it is constantly to be met with, but a single quarter is rare.

Originally a single quarter was drawn to contain the full fourth part of the shield, but with the more modern tendency to reduce the size of all charges, its area has been somewhat diminished. Whilst a quarter will only be found within a plain partition line, a field divided quarterly (occasionally, but I think hardly so correctly, termed "per cross") is not so limited. Examples of quarterly fields will be found in the historic shield of De Vere (Fig. 205) and De Mandeville. An irregular partition line is often introduced in a new grant to conjoin quarterings borne without authority into one single coat. The diminutive of the quarter is the canton (Fig. 206), and the diminutive of that the chequer of a chequy field (Fig. 207).