Greyhounds (Figs. 372 and 373) are, of course, very frequently met with, and amongst the instances which can be mentioned are the arms of Clayhills, Hughes-Hunter of Plas Coch, and Hunter of Hunterston. A curious coat of arms will be found under the name of Udney of that Ilk, registered in the Lyon Office, namely: "Gules, two greyhounds counter-salient argent, collared of the field, in the inner point a stag's head couped and attired with ten tynes, all between the three fleurs-de-lis, two in chief and one in base, or." Another very curious coat of arms is registered as the design of the reverse of the seal of the Royal Burgh of Linlithgow, and is: "Or, a greyhound bitch sable, chained to an oak-tree within a loch proper." This curious coat of arms, however, being the reverse of the seal, is seldom if ever made use of.

Two bloodhounds are the supporters to the arms of Campbell of Aberuchill.

The dog may be salient, that is, springing, its hind-feet on the ground; passant, when it is sometimes known as trippant, otherwise walking; and courant when it is at full speed. It will be found occasionally couchant or lying down, but if depicted chasing another animal (as in the arms of Echlin) it is described as "in full chase," or "in full course."

A mastiff will be found in the crest of Crawshay, and there is a well-known crest of a family named Phillips which is "a dog sejant regardant surmounted by a bezant charged with a representation of a dog saving a man from drowning." Whether this crest has any official authority or not I do not know, but I should imagine it is highly doubtful.

Foxhounds appear as the supporters of Lord Hindlip; and when depicted with its nose to the ground a dog is termed "a hound on scent."

A winged greyhound is stated to be the crest of a family of Benwell. A greyhound "courant" will be found in the crests of Daly and Watney; and a curious crest is that of Biscoe, which is a greyhound seizing a hare. The crest of Anderson, until recently borne by the Earl of Yarborough, is a water spaniel.

The sea-dog (Fig. 374) is a most curious animal. It is represented much as the talbot, but with scales, webbed feet, and a broad scaly tail like a beaver. In my mind there is very little doubt that the sea-dog is really the early heraldic attempt to represent a beaver, and I am confirmed in that opinion by the arms of the city of Oxford. There has been considerable uncertainty as to what the sinister supporter was intended to represent. A reference to the original record shows that a beaver is the real supporter, but the representation of the animal, which in form has varied little, is very similar to that of a sea-dog. The only instances I am aware of in British heraldry in which it occurs under the name of a sea-dog are the supporters of the Barony of Stourton and the crest of Dodge[17] (Plate VI.).

BULLS

The bull (Figs. 375 and 376), and also the calf, and very occasionally the cow and the buffalo, have their allotted place in heraldry. They are amongst the few animals which can never be represented proper, inasmuch as in its natural state the bull is of very various colours. And yet there is an exception to even this apparently obvious fact, for the bulls connected with or used either as crests, badges, or supporters by the various branches of the Nevill family are all pied bulls ["Arms of the Marquis of Abergavenny: Gules, on a saltire argent, a rose of the field, barbed and seeded proper. Crest: a bull statant argent, pied sable, collared and chain reflexed over the back or. Supporters; two bulls argent, pied sable, armed, unguled, collared and chained, and at the end of the chain two staples or. Badges: on the dexter a rose gules, seeded or, barbed vert; on the sinister a portcullis or. Motto: 'Ne vile velis.'"] The bull in the arms of the town of Abergavenny, which are obviously based upon the arms and crest of the Marquess of Abergavenny, is the same.

Examples of the bull will be found in the arms of Verelst, Blyth, and Ffinden. A bull salient occurs in the arms of De Hasting ["Per pale vert and or, a bull salient counterchanged"]. The arms of the Earl of Shaftesbury show three bulls, which happen to be the quartering for Ashley. This coat of arms affords an instance, and a striking one, of the manner in which arms have been improperly assumed in England. The surname of the Earl of Shaftesbury is Ashley-Cooper. It may be mentioned here in passing, through the subject is properly dealt with elsewhere in the volume, that in an English sub-quarterly coat for a double name the arms for the last and most important name are the first and fourth quarterings. But Lord Shaftesbury himself is the only person who bears the name of Cooper, all other members of the family except his lordship being known by the name of Ashley only. Possibly this may be the reason which accounts for the fact that by a rare exception Lord Shaftesbury bears the arms of Ashley in the first and fourth quarters, and Cooper in the second and third. But by a very general mistake these arms of Ashley ["Argent, three bulls passant sable, armed and unguled or"] were until recently almost invariably described as the arms of Cooper. The result has been that during the last century they were "jumped" right and left by people of the name of Cooper, entirely in ignorance of the fact that the arms of Cooper (if it were, as one can only presume, the popular desire to indicate a false relationship to his lordship) are: "Gules, a bend engrailed between six lions rampant or." The ludicrous result has been that to those who know, the arms have stood self-condemned, and in the course of time, as it has become necessary for these Messrs. Cooper to legalise these usurped insignia, the new grants, differentiated versions of arms previously in use, have nearly all been founded upon this Ashley coat. At any rate there must be a score or more Cooper grants with bulls as the principal charges, and innumerable people of the name of Cooper are still using without authority the old Ashley coat pure and simple.

The bull as a crest is not uncommon, belonging amongst other families to Ridley, Sykes, and De Hoghton; and the demi-bull, and more frequently the bull's head, are often met with. A bull's leg is the crest of De la Vache, and as such appears upon two of the early Garter plates. Winged bulls are the supporters of the Butchers' Livery Company. A bull's scalp occurs upon a canton over the arms of Cheney, a coat quartered by Johnston and Cure.

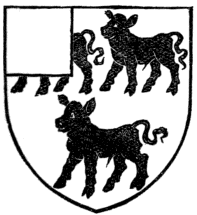

Fig. 378.—Armorial bearings of John Henry Metcalfe, Esq.: Argent, three calves passant sable, a canton gules.

The ox seldom occurs, except that, in order sometimes to preserve a pun, a bovine animal is sometimes so blazoned, as in the case of the arms of the City of Oxford. Cows also are equally rare, but occur in the arms of Cowell ["Ermine, a cow statant gules, within a bordure sable, bezantée"] and in the modern grants to the towns of Rawtenstall and Cowbridge. Cows' heads appear on the arms of Veitch ["Argent, three cows' heads erased sable"], and these were transferred to the cadency bordure of the Haig arms when these were rematriculated for Mr. H. Veitch Haig.

Calves are of much more frequent occurrence than cows, appearing in many coats of arms in which they are a pun upon the name. They will be found in the arms of Vaile and Metcalfe (Fig. 378). Special attention may well be drawn to the last-mentioned illustration, inasmuch as it is by Mr. J. H. Metcalfe, whose heraldic work has obtained a well-deserved reputation. A bull or cow is termed "armed" if the horns are of a different tincture from the head. The term "unguled" applies to the hoofs, and "ringed" is used when, as is sometimes the case, a ring passes through the nostrils. A bull's head is sometimes found caboshed (Fig. 377), as in the crest of Macleod, or as in the arms of Walrond. The position of the tail is one of those matters which are left to the artist, and unless the blazon contains any statement to the contrary, it may be placed in any convenient position.

STAGS

The stag, using the term in its generic sense, under the various names of stag, deer, buck, roebuck, hart, doe, hind, reindeer, springbok, and other varieties, is constantly met with in British armory, as well as in that of other countries.

In the specialised varieties, such as the springbok and the reindeer, naturally an attempt is made to follow the natural animal in its salient peculiarities, but as to the remainder, heraldry knows little if any distinction after the following has been properly observed. The stag, which is really the male red deer, has horns which are branched with pointed branches from the bottom to the top; but a buck, which is the fallow deer, has broad and flat palmated horns. Anything in the nature of a stag must be subject to the following terms. If lying down it is termed "lodged" (Fig. 379), if walking it is termed "trippant" (Fig. 380), if running it is termed "courant" (Fig. 381), or "at speed" or "in full chase." It is termed "salient" when springing (Fig. 382), though the term "springing" is sometimes employed, and it is said to be "at gaze" when statant with the head turned to face the spectator (Fig. 383); but it should be noted that a stag may also be "statant" (Fig. 384); and it is not "at gaze" unless the head is turned round. When it is necessary owing to a difference of tincture or for other reasons to refer to the horns, a stag or buck is described as "attired" of such and such a colour, whereas bulls, rams, and goats are said to be "armed."

When the stag is said to be attired of ten or any other number of tynes, it means that there are so many points to its horns. Like other cloven-footed animals, the stag can be unguled of a different colour.

The stag's head is very frequently met with, but it will be almost more frequently found as a stag's head caboshed (Fig. 385). In these cases the head is represented affronté and removed close behind the ears, so that no part of the neck is visible. The stag's head caboshed occurs in the arms of Cavendish and Stanley, and also in the arms of Legge, Earl of Dartmouth. Figs. 386 and 387 are examples of other heads.

The attires of a stag are to be found either singly (as in the arms of Boyle) or in the form of a pair attached to the scalp. The crest of Jeune affords an instance of a scalp. The hind or doe (Fig. 388) is sometimes met with, as in the crest of Hatton, whilst a hind's head is the crest of Conran.

The reindeer (Fig. 389) is less usual, but reindeer heads will be found in the arms of Fellows. It, however, appears as a supporter for several English peers. Winged stags (Fig. 390) were the supporters of De Carteret, Earls of Granville, and "a demi-winged stag gules, collared argent," is the crest of Fox of Coalbrookdale, co. Salop.

Much akin to the stag is the antelope, which, unless specified to be an heraldic antelope, or found in a very old coat, is usually represented in the natural form of the animal, and subject to the foregoing rules.

Heraldic Antelope.—This animal (Figs. 391, 392, and 393) is found in English heraldry more frequently as a supporter than as a charge. As an instance, however, of the latter form may be mentioned the family of Dighton (Lincolnshire): "Per pale argent and gules, an heraldic antelope passant counterchanged." It bears little if any relation to the real animal, though there can be but small doubt that the earliest forms originated in an attempt to represent an antelope or an ibex. Since, however, heraldry has found a use for the real antelope, it has been necessary to distinguish it from the creations of the early armorists, which are now known as heraldic antelopes. Examples will be found in the supporters of Lord Carew, in the crest of Moresby, and of Bagnall.

The difference chiefly consists in the curious head and horns and in the tail, the heraldic antelope being an heraldic tiger, with the feet and legs similar to those of a deer, and with two straight serrated horns.

Ibex.—This is another form of the natural antelope, but with two saw-edged horns projecting from the forehead.

A curious animal, namely, the sea-stag, is often met with in German heraldry. This is the head, antlers, fore-legs, and the upper part of the body of a stag conjoined to the fish-tail end of a mermaid. The only instance I am aware of in which it occurs in British armory is the case of the arms of Marindin, which were recently matriculated in Lyon Register (Fig. 394). This coat, however, it should be observed, is really of German or perhaps of Swiss origin.

THE RAM AND GOAT

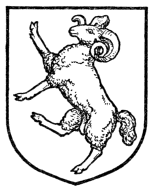

The ram (Figs. 395 and 396), the consideration of which must of necessity include the sheep (Fig. 397), the Paschal lamb (Fig. 398), and the fleece (Fig. 399), plays no unimportant part in armory. The chief heraldic difference between the ram and the sheep, to some extent, in opposition to the agricultural distinctions, lies in the fact that the ram is always represented with horns and the sheep without. The lamb and the ram are always represented with the natural tail, but the sheep is deprived of it. A ram can of course be "armed" (i.e. with the horns of a different colour) and "unguled," but the latter will seldom be found to be the case. The ram, the sheep, and the lamb will nearly always be found either passant or statant, but a demi-ram is naturally represented in a rampant posture, though in such a case the word "rampant" is not necessary in the blazon.

Occasionally, as in the crest of Marwood, the ram will be found couchant. As a charge upon a shield the ram will be found in the arms of Sydenham ["Argent, three rams passant sable"], and a ram couchant occurs in the arms of Pujolas (granted 1762) ["Per fess wavy azure and argent, in base on a mount vert, a ram couchant sable, armed and unguled or, in chief three doves proper"]. The arms of Ramsey ["Azure, a chevron between three rams passant or"] and the arms of Harman ["Sable, a chevron between six rams counter-passant two and two argent, armed and unguled or"] are other instances in which rams occur. A sheep occurs in the arms of Sheepshanks ["Azure, a chevron erminois between in chief three roses and in base a sheep passant argent. Crest: on a mount vert, a sheep passant argent"].

The lamb, which is by no means an unusual charge in Welsh coats of arms, is most usually found in the form of a "paschal lamb" (Fig. 398), or some variation evidently founded thereupon.

The fleece—of course originally of great repute as the badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece—has in recent years been frequently employed in the grants of arms to towns or individuals connected with the woollen industry.

The demi-ram and the demi-lamb are to be found as crests, but far more usual are rams' heads, which figure, for example, in the arms of Ramsden, and in the arms of the towns of Huddersfield, and Barrow-in-Furness. The ram's head will sometimes be found caboshed, as in the arms of Ritchie and Roberts.

Perhaps here reference may fittingly be made to the arms granted by Lyon Office in 1812 to Thomas Bonar, co. Kent ["Argent, a saltire and chief azure, the last charged with a dexter hand proper, vested with a shirt-sleeve argent, issuing from the dexter chief point, holding a shoulder of mutton proper to a lion passant or, all within a bordure gules"].

The Goat (Figs. 401-403) is very frequently met with in armory. Its positions are passant, statant, rampant, and salient. When the horns are of a different colour it is said to be "armed."

OTHER ANIMALS

The Elephant is by no means unusual in heraldry, appearing as a crest, as a charge, and also as a supporter. Nor, strange to say, is its appearance exclusively modern. The elephant's head, however, is much more frequently met with than the entire animal. Heraldry generally finds some way of stereotyping one of its creations as peculiarly its own, and in regard to the elephant, the curious "elephant and castle" (Fig. 404) is an example, this latter object being, of course, simply a derivative of the howdah of Indian life. Few early examples of the elephant omit the castle. The elephant and castle is seen in the arms of Dumbarton and in the crest of Corbet.

A curious practice, the result of pure ignorance, has manifested itself in British armory. As will be explained in the chapter upon crests, a large proportion of German crests are derivatives of the stock basis of two bull's horns, which formed a recognised ornament for a helmet in Viking and other pre-heraldic days. As heraldry found its footing it did not in Germany displace those horns, which in many cases continued alone as the crest or remained as a part of it in the form of additions to other objects. The craze for decoration at an early period seized upon the horns, which carried repetitions of the arms or their tinctures. As time went on the decoration was carried further, and the horns were made with bell-shaped open ends to receive other objects, usually bunches of feathers or flowers. So universal did this custom become that even when nothing was inserted the horns came to be always depicted with these open mouths at their points. But German heraldry now, as has always been the case, simply terms the figures "horns." In course of time German immigrants made application for grants of arms in this country, which, doubtless, were based upon other German arms previously in use, but which, evidence of right not being forthcoming, could not be recorded as borne of right, and needed to be granted with alteration as a new coat. The curious result has been that these horns have been incorporated in some number of English grants, but they have universally been described as elephants' proboscides, and are now always so represented in this country. A case in point is the crest of Verelst, and another is the crest of Allhusen.

Elephants' tusks have also been introduced into grants, as in the arms of Liebreich (borne in pretence by Cock) and Randles ["Or, a chevron wavy azure between three pairs of elephants' tusks in saltire proper"].

The Hare (Fig. 405) is but rarely met with in British armory. It appears in the arms of Cleland, and also in the crest of Shakerley, Bart. ["A hare proper resting her forefeet on a grab or"]. A very curious coat ["Argent, three hares playing bagpipes gules"] belongs to an ancient Derbyshire family FitzErcald, now represented (through the Sacheverell family) by Coke of Trussley, who quarter the FitzErcald shield.

The Rabbit (Fig. 406), or, as it is more frequently termed heraldically, the Coney, appears more frequently in heraldry than the hare, being the canting charge on the arms of Coningsby, Cunliffe ["Sable, three conies courant argent"], and figuring also as the supporters of Montgomery Cunningham ["Two conies proper"].

The Squirrel (Fig. 407) occurs in many English coats of arms. It is always sejant, and very frequently cracking a nut.

The Ape is not often met with, except in the cases of the different families of the great Fitz Gerald clan. It is usually the crest, though the Duke of Leinster also has apes as supporters. One family of Fitzgerald, however, bear it as a charge upon the shield ["Gules, a saltire invected per pale argent and or, between four monkeys statant of the second, environed with a plain collar and chained of the second. Mantling gules and argent. Crest: on a wreath of the colours, a monkey as in the arms, charged on the body with two roses, and resting the dexter fore-leg on a saltire gules. Motto: 'Crom-a-boo'"], and the family of Yorke bear an ape's head for a crest.

The ape is usually met with "collared and chained" (Fig. 408), though, unlike any other animal, the collar of an ape environs its loins and not its neck. A winged ape is included in Elvin's "Dictionary of Heraldry" as a heraldic animal, but I am not aware to whom it is assigned.

The Brock or Badger (Fig. 409) figures in some number of English arms. It is most frequently met with as the crest of Brooke, but will be also found in the arms or crests of Brocklebank and Motion.

The Otter (Fig. 410) is not often met with except in Scottish coats, but an English example is that of Sir George Newnes, and a demi-otter issuant from a fess wavy will be found quartered by Seton of Mounie.

An otter's head, sometimes called a seal's head, for it is impossible to distinguish the heraldic representations of the one or the other, appears in many coats of arms of different families of the name of Balfour, and two otters are the supporters belonging to the head of the Scottish house of Balfour.

The Ermine, the Stoat, and the Weasel, &c., are not very often met with, but the ermine appears as the crest of Crawford and the marten as the crest of a family of that name.

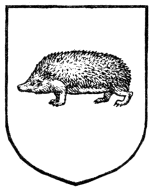

The Hedgehog, or, as it is usually heraldically termed, the Urcheon (Fig. 411), occurs in some number of coats. For example, in the arms of Maxwell ["Argent, an eagle with two heads displayed sable, beaked and membered gules, on the breast an escutcheon of the first, charged with a saltire of the second, surcharged in the centre with a hurcheon (hedgehog) or, all within a bordure gules"], Harris, and as the crest of Money-Kyrle.

The Beaver has been introduced into many coats of late years for those connected in any way with Canada. It figures in the arms of Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, and in the arms of Christopher.

The beaver is one of the supporters of the city of Oxford, and is the sole charge in the arms of the town of Biberach (Fig. 412). Originally the arms were: "Argent, a beaver azure, crowned and armed gules," but the arms authorised by the Emperor Frederick IV., 18th July 1848, were: "Azure, a beaver or."

Fig. 412.—Arms of the town of Biberach. (From Ulrich Reichenthal's Concilium von Constanz, Augsburg, 1483.)

It is quite impossible, or at any rate very unnecessary, to turn a work on armory into an Illustrated Guide to Natural History, which would be the result if under the description of heraldic charges the attempt were made to deal with all the various animals which have by now been brought to the armorial fold, owing to the inclusion of each for special and sufficient reasons in one or two isolated grants.

Far be it from me, however, to make any remark which should seem to indicate the raising of any objection to such use. In my opinion it is highly admirable, providing there is some definite reason in each case for the introduction of these strange animals other than mere caprice. They add to the interest of heraldry, and they give to modern arms and armory a definite status and meaning, which is a relief from the endless monotony of meaningless lions, bends, chevrons, mullets, and martlets.

But at the same time the isolated use in a modern grant of such an animal as the kangaroo does not make it one of the peculiarly heraldic menagerie, and consequently such instances must be dismissed herein with brief mention, particularly as many of these creatures heraldically exist only as supporters, in which chapter some are more fully discussed. Save as a supporter, the only instances I know of the Kangaroo are in the coat of Moore and in the arms of Arthur, Bart.

The Zebra will be found as the crest of Kemsley.

The Camel, which will be dealt with later as a supporter, in which form it appears in the arms of Viscount Kitchener, the town of Inverness (Fig. 251), and some of the Livery Companies, also figures in the reputed but unrecorded arms of Camelford, and in the arms of Cammell of Sheffield and various other families of a similar name.

The fretful Porcupine was borne ["Gules, a porcupine erect argent, tusked, collared, and chained or"] by Simon Eyre, Lord Mayor of London in 1445: and the creature also figures as one of the supporters and the crest of Sidney, Lord De Lisle and Dudley.

The Bat (Fig. 413) will be found in the arms of Heyworth and as the crest of a Dublin family named Wakefield.

The Tortoise occurs in the arms of a Norfolk family named Gandy, and is also stated by Papworth to occur in the arms of a Scottish family named Goldie. This coat, however, is not matriculated. It also occurs in the crests of Deane and Hayne.

The Springbok, which is one of the supporters of Cape Colony, and two of which are the supporters of Viscount Milner, is also the crest of Randles ["On a wreath of the colours, a springbok or South African antelope statant in front of an assegai erect all proper"].

The Rhinoceros occurs as one of the supporters of Viscount Colville of Culross, and also of the crest of Wade, and the Hippopotamus is one of the supporters of Speke.

The Crocodile, which is the crest and one of the supporters of Speke, is also the crest of Westcar ["A crocodile proper, collared and chained or"].

The Alpaca, and also two Angora Goats' heads figure in the arms of Benn.

The Rat occurs in the arms of Ratton,[18] which is a peculiarly good example of a canting coat.

The Mole, sometimes termed a moldiwarp, occurs in the arms of Mitford ["Argent, a fess sable between three moles displayed sable"].

CHAPTER XIII

MONSTERS

The heraldic catalogue of beasts runs riot when we reach those mythical or legendary creatures which can only be summarised under the generic term of monsters. Most mythical animals, however, can be traced back to some comparable counterpart in natural history.

The fauna of the New World was of course unknown to those early heraldic artists in whose knowledge and imagination, no less than in their skill (or lack of it) in draughtsmanship, lay the nativity of so much of our heraldry. They certainly thought they were representing animals in existence in most if not in all cases, though one gathers that they considered many of the animals they used to be misbegotten hybrids. Doubtless, working on the assumption of the mule as the hybrid of the horse and the ass, they jumped to the conclusion that animals which contained salient characteristics of two other animals which they knew were likewise hybrids. A striking example of their theories is to be found in the heraldic Camelopard, which was anciently devoutly believed to be begotten by the leopard upon the camel. A leopard they would be familiar with, also the camel, for both belong to that corner of the world where the north-east of the African Continent, the south-east of Europe, and the west of Asia join, where were fought out the wars of the Cross, and where heraldry took on itself a definite being. There the known civilisations of the world met, taking one from the other knowledge, more or less distorted, ideas and wild imaginings. A stray giraffe was probably seen by some journeyer up the Nile, who, unable to otherwise account for it, considered and stated the animal to be the hybrid offspring of the leopard and camel. Another point needs to be borne in mind. Earlier artists were in no way fettered by any supposed necessity for making their pictures realistic representations. Realism is a modernity. Their pictures were decoration, and they thought far more of making their subject fit the space to be decorated than of making it a "speaking likeness."

Nevertheless, their work was not all imagination. In the Crocodile we get the basis of the dragon, if indeed the heraldic dragon be not a perpetuation of ancient legends, or even perhaps of then existing representations of those winged antediluvian animals, the fossilised remains of which are now available. Wings, however, need never be considered a difficulty. It has ever been the custom (from the angels of Christianity to the personalities of Mercury and Pegasus) to add wings to any figure held in veneration. Why, it would be difficult to say, but nevertheless the fact remains.

The Unicorn, however, it is not easy to resolve into an original basis, because until the seventeenth century every one fondly believed in the existence of the animal. Mr. Beckles Wilson appears to have paid considerable attention to the subject, and was responsible for the article "The Rise of the Unicorn" which recently appeared in Cassel's Magazine. That writer traces the matter to a certain extent from non-heraldic sources, and the following remarks, which are taken from the above article, are of considerable interest:—

"The real genesis of the unicorn was probably this: at a time when armorial bearings were becoming an indispensable part of a noble's equipment, the attention of those knights who were fighting under the banner of the Cross was attracted to the wild antelopes of Syria and Palestine. These animals are armed with long, straight, spiral horns set close together, so that at a side view they appeared to be but a single horn. To confirm this, there are some old illuminations and drawings extant which endow the early unicorn with many of the attributes of the deer and goat kind. The sort of horn supposed to be carried by these Eastern antelopes had long been a curiosity, and was occasionally brought back as a trophy by travellers from the remote parts of the earth. There is a fine one to be seen to-day at the abbey of St. Denis, and others in various collections in Europe. We now know these so-called unicorn's horns, usually carved, to belong to that marine monster the narwhal, or sea-unicorn. But the fable of a breed of horned horses is at least as old as Pliny" [Had the "gnu" anything to do with this?], "and centuries later the Crusaders, or the monkish artists who accompanied them, attempted to delineate the marvel. From their first rude sketches other artists copied; and so each presentment was passed along, until at length the present form of the unicorn was attained. There was a time—not so long ago—when the existence of the unicorn was as implicitly believed in as the camel or any other animal not seen in these latitudes; and the translators of the Bible set their seal upon the legend by translating the Hebrew word reem (which probably meant a rhinoceros) as 'unicorn.' Thus the worthy Thomas Fuller came to consider the existence of the unicorn clearly proved by the mention of it in Scripture! Describing the horn of the animal, he writes, 'Some are plain, as that of St. Mark's in Venice; others wreathed about it, which probably is the effect of age, those wreaths being but the wrinkles of most vivacious unicorns. The same may be said of the colour: white when newly taken from the head; yellow, like that lately in the Tower, of some hundred years' seniority; but whether or no it will soon turn black, as that of Plinie's description, let others decide.'

"All the books on natural history so late as the seventeenth century describe at length the unicorn; several of them carefully depict him as though the artist had drawn straight from the life.

"If art had stopped here, the wonder of the unicorn would have remained but a paltry thing after all. His finer qualities would have been unrecorded, and all his virtues hidden. But, happily, instead of this, about the animal first conceived in the brain of a Greek (as Pegasus also was), and embodied through the fertile fancy of the Crusader, the monks and heraldists of the Middle Ages devised a host of spiritual legends. They told of his pride, his purity, his endurance, his matchless spirit.

"'The greatnesse of his mynde is such that he chooseth rather to dye than be taken alive.' Indeed, he was only conquerable by a beautiful maiden. One fifteenth-century writer gives a recipe for catching a unicorn. 'A maid is set where he hunteth and she openeth her lap, to whom the unicorn, as seeking rescue from the force of the hunter, yieldeth his head and leaveth all his fierceness, and resteth himself under her protection, sleepeth until he is taken and slain.' But although many were reported to be thus enticed to their destruction, only their horns, strange to say, ever reached Europe. There is one in King Edward's collection at Buckingham Palace.

"Naturally, the horn of such an animal was held a sovereign specific against poison, and 'ground unicorn's horn' often figures in mediæval books of medicine.

"There was in Shakespeare's time at Windsor Castle the 'horn of a unicorn of above eight spans and a half in length, valued at above £10,000.' This may have been the one now at Buckingham Palace. One writer, describing it, says:—

"'I doe also know that horn the King of England possesseth to be wreathed in spires, even as that is accounted in the Church of St. Dennis, than which they suppose none greater in the world, and I never saw anything in any creature more worthy praise than this horne. It is of soe great a length that the tallest man can scarcely touch the top thereof, for it doth fully equal seven great feet. It weigheth thirteen pounds, with their assize, being only weighed by the gesse of the hands it seemeth much heavier.'

"Spenser, in the 'Faerie Queen,' thus describes a contest between the unicorn and the lion:—