Heraldically, no difference is made in depicting the raven, the rook, and the crow; and examples of the Crow will be found in the arms of Crawhall, and of the Rook in the crest of Abraham. The arms of the Yorkshire family of Creyke are always blazoned as rooks, but I am inclined to think they may possibly have been originally creykes, or corn-crakes.

The Cornish Chough is very much more frequently met with than either the crow, rook, or raven, and it occurs in the arms of Bewley, the town of Canterbury, and (as a crest) of Cornwall.

It can only be distinguished from the raven in heraldic representations by the fact that the Cornish chough is always depicted and frequently blazoned as "beaked and legged gules," as it is found in its natural state.

The Owl (Fig. 475), too, is a very favourite bird. It is always depicted with the face affronté, though the body is not usually so placed. It occurs in the arms of Leeds—which, by the way, are an example of colour upon colour—Oldham, and Dewsbury. In the crest of Brimacombe the wings are open, a most unusual position.

The Lark will be found in many cases of arms or crests for families of the name of Clarke.

The Parrot, or, as it is more frequently termed heraldically, the Popinjay (Fig. 476), will be found in the arms of Lumley and other families. It also occurs in the arms of Curzon: "Argent, on a bend sable three popinjays or, collared gules."

There is nothing about the bird, or its representations, which needs special remark, and its usual heraldic form follows nature pretty closely.

The Moorcock or Heathcock is curious, inasmuch as there are two distinct forms in which it is depicted. Neither of them are correct from the natural point of view, and they seem to be pretty well interchangeable from the heraldic point of view. The bird is always represented with the head and body of an ordinary cock, but sometimes it is given the wide flat tail of black game, and sometimes a curious tail of two or more erect feathers at right angles to its body (Fig. 477).

Though usually represented close, it occurs sometimes with open wings, as in the crest of a certain family of Moore.

Many other birds are to be met with in heraldry, but they have nothing at all especial in their bearing, and no special rules govern them.

The Lapwing, under its alternative names of Peewhit, Plover, and Tyrwhitt, will be found in the arms of Downes, Tyrwhitt, and Tweedy.

The Pheasant will be found in the crest of Scott-Gatty, and the Kingfisher in many cases of arms of the name of Fisher.

The Magpie occurs in the arms of Dusgate, and in those of Finch.

Woodward mentions an instance in which the Bird of Paradise occurs (p. 267); "Argent, on a terrace vert, a cannon mounted or, supporting a Bird of Paradise proper" [Rjevski and Yeropkin]; and the arms of Thornton show upon a canton the Swedish bird tjader: "Ermine, a chevron sable between three hawthorn trees eradicated proper, a canton or, thereon the Swedish bird tjader, or cock of the wood, also proper." Two similar birds were granted to the first Sir Edward Thornton, G.C.B., as supporters, he being a Knight Grand Cross.

Fig. 478.—The "Shield for Peace" of Edward the Black Prince (d. 1376): Sable, three ostrich feathers with scrolls argent. (From his tomb in Canterbury Cathedral.)

Single feathers as charges upon a shield are sometimes met with, as in the "shield for peace" of Edward the Black Prince (Fig. 478) and in the arms of Clarendon. These two examples are, however, derivatives from the historic ostrich-feather badges of the English Royal Family, and will be more conveniently dealt with later when considering the subject of badges. The single feather enfiled by the circlet of crosses patée and fleurs-de-lis, which is borne upon a canton of augmentation upon the arms of Gull, Bart., is likewise a derivative, but feathers as a charge occur in the arms of Jervis: "Argent, six ostrich feathers, three, two, and one sable." A modern coat founded upon this, in which the ostrich feathers are placed upon a pile, between two bombshells fracted in base, belongs to a family of a very similar name, and the crest granted therewith is a single ostrich feather between two bombs fired. Cock's feathers occur as charges in the arms of Galpin.

In relation to the crest, feathers are constantly to be found, which is not to be wondered at, inasmuch as fighting and tournament helmets, when actually in use, frequently did not carry the actual crests of the owners, but were simply adorned with the plume of ostrich feathers. A curious instance of this will be found in the case of the family of Dymoke of Scrivelsby, the Honourable the King's Champions. The crest is really: "Upon a wreath of the colours, the two ears of an ass sable," though other crests ["1. a sword erect proper; 2. a lion as in the arms"] are sometimes made use of. When the Champion performs his service at a Coronation the shield which is carried by his esquire is not that of his sovereign, but is emblazoned with his personal arms of Dymoke: "Sable, two lions passant in pale argent, ducally crowned or." The helmet of the Champion is decorated with a triple plume of ostrich feathers and not with the Dymoke crest. In old representations of tournaments and warfare the helmet will far oftener be found simply adorned with a plume of ostrich feathers than with a heritable crest, and consequently such a plume has remained in use as the crest of a very large number of families. This point is, however, more fully dealt with in the chapter upon crests.

The plume of ostrich feathers is, moreover, attributed as a crest to a far greater number of families than it really belongs to, because if a family possessed no crest the helmet was generally ornamented with a plume of ostrich feathers, which later generations have accepted and adopted as their heritable crest, when it never possessed such a character. A notable instance of this will be found in the crest of Astley, as given in the Peerage Books.

The number of feathers in a plume requires to be stated; it will usually be found to be three, five, or seven, though sometimes a larger number are met with. When it is termed a double plume they are arranged in two rows, the one issuing above the other, and a triple plume is arranged in three rows; and though it is correct to speak of any number of feathers as a plume, it will usually be found that the word is reserved for five or more, whilst a plume of three feathers would more frequently be termed three ostrich feathers. Whilst they are usually white, they are also found of varied colours, and there is even an instance to be met with of ostrich feathers of ermine. When the feathers are of different colours they need to be carefully blazoned; if alternately, it is enough to use the word "alternately," the feather at the extreme dexter side being depicted of the colour first mentioned. In a plume which is of three colours, care must be used in noting the arrangement of the colours, the colours first mentioned being that of the dexter feather; the others then follow from dexter to sinister, the fourth feather commencing the series of colours again. If any other arrangement of the colours occurs it must be specifically detailed. The rainbow-hued plume from which the crest of Sir Reginald Barnewall[19] issues is the most variegated instance I have met with.

Two peacock's feathers in saltire will be found in the crest of a family of Gatehouse, and also occur in the crest of Crisp-Molineux-Montgomerie. The pen in heraldry is always of course of the quill variety, and consequently should not be mistaken for a single feather. The term "penned" is used when the quill of a feather is of a different colour from the remainder of it. Ostrich and other feathers are very frequently found on either side of a crest, both in British and Continental armory; but though often met with in this position, there is nothing peculiar about this use in such character. German heraldry has evolved one use of the peacock's feather, or rather for the eye from the peacock's feather, which happily has not yet reached this country. It will be found adorning the outer edges of every kind of object, and it even occurs on occasion as a kind of dorsal fin down the back of animals. Bunches of cock's feathers are also frequently made use of for the same purpose. There has been considerable diversity in the method of depicting the ostrich feather. In its earliest form it was stiff and erect as if cut from a piece of board (Fig. 478), but gradually, as the realistic type of heraldic art came into vogue, it was represented more naturally and with flowing and drooping curves. Of later years, however, we have followed the example of His Majesty when Prince of Wales and reverted to the earlier form, and it is now very general to give to the ostrich feather the stiff and straight appearance which it originally possessed when heraldically depicted. Occasionally a plume of ostrich feathers is found enclosed in a "case," that is, wrapped about the lower part as if it were a bouquet, and this form is the more usual in Germany. In German heraldry these plumes are constantly met with in the colours of the arms, or charged with the whole or a part of the device upon the shield. It is not a common practice in this country, but an instance of it will be found in the arms of Lord Waldegrave: "Per pale argent and gules. Crest: out of a ducal coronet or a plume of five ostrich feathers, the first two argent, the third per pale argent and gules, and the last two gules."

CHAPTER XV

FISH

Heraldry has a system of "natural" history all its very own, and included in the comprehensive heraldic term of fish are dolphins, whales, and other creatures. There are certain terms which apply to heraldic fish which should be noted. A fish in a horizontal position is termed "naiant," whether it is in or upon water or merely depicted as a charge upon a shield. A fish is termed "hauriant" if it is in a perpendicular position, but though it will usually be represented with the head upwards in default of any specific direction to the contrary, it by no means follows that this is always the case, and it is more correct to state whether the head is upwards or downwards, a practice which it is usually found will be conformed to. When the charges upon a shield are simply blazoned as "fish," no particular care need be taken to represent any particular variety, but on the other hand it is not in such cases usual to add any distinctive signs by which a charge which is merely a fish might become identified as any particular kind of fish.

The heraldic representations of the Dolphin are strangely dissimilar from the real creature, and also show amongst themselves a wide variety and latitude. It is early found in heraldry, and no doubt its great importance in that science is derived from its usage by the Dauphins of France. Concerning its use by these Princes there are all sorts of curious legends told, the most usual being that recited by Berry.

Woodward refers to this legend, but states that "in 1343 King Philip of France purchased the domains of Humbert III., Dauphin de Viennois," and further remarks that the legend in question "seems to be without solid foundation." But neither Woodward nor any other writer seems to have previously suggested what is doubtless the true explanation, that the title of Dauphin and the province of Viennois were a separate dignity of a sovereign character, to which were attached certain territorial and sovereign arms ["Or, a dolphin embowed azure, finned and langued gules"]. The assumption of these sovereign arms with the sovereignty and territory to which they belonged, was as much a matter of course as the use of separate arms for the Duchy of Lancaster by his present Majesty King Edward VII., or the use of separate arms for his Duchy of Cornwall by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales.

Berry is wrong in asserting that no other family were permitted to display the dolphin in France, because a very similar coat (but with the dolphin lifeless) to that of the Dauphin was quartered by the family of La Tour du Pin, who claimed descent from the Dauphins d'Auvergne, another ancient House which originally bore the sovereign title of Dauphin. A dolphin was the charge upon the arms of the Grauff von Dälffin (Fig. 481).

The dolphin upon this shield, as also that in the coat of the Dauphin of France, is neither naiant nor hauriant, but is "embowed," that is, with the tail curved towards the head. But the term "embowed" really signifies nothing further than "bent" in some way, and as a dolphin is never heraldically depicted straight, it is always understood to be and usually is termed "embowed," though it will generally be "naiant embowed" (Fig. 479), or "hauriant embowed" (Fig. 480). The dolphin occurs in the arms of many British families, e.g. in the arms of Ellis, Monypenny, Loder-Symonds, Symonds-Taylor, Fletcher, and Stuart-French.

Woodward states that the dolphin is used as a supporter by the Trevelyans, Burnabys, &c. In this statement he is clearly incorrect, for neither of those families are entitled to or use supporters. But his statement probably originates in the practice which in accordance with the debased ideas of artistic decoration at one period added all sorts of fantastic objects to the edges of a shield for purely decorative (!) purposes. The only instance within my knowledge in which a dolphin figures as a heraldic supporter will be found in the case of the arms of Waterford.

Fig. 481.—Arms of the Grauff von Dälffin lett och in Dalffinat (Count von Dälffin), which also lies in Dauphiné (from Grünenberg's "Book of Arms"): Argent, a dolphin azure within a bordure compony of the first and second.

The Whale is seldom met with in British armory, one of its few appearances being in the arms of Whalley, viz.: "Argent, three whales' heads erased sable."

The crest of an Irish family named Yeates is said to be: "A shark issuant regardant swallowing a man all proper," and the same device is also attributed to some number of other families.

Another curious piscine coat of arms is that borne, but still unmatriculated, by the burgh of Inveraray, namely: "The field is the sea proper, a net argent suspended to the base from the dexter chief and the sinister fess points, and in chief two and in base three herrings entangled in the net."

Salmon are not infrequently met with, but they need no specific description. They occur in the arms of Peebles,[20] a coat of arms which in an alternative blazon introduces to one's notice the term "contra-naiant." The explanation of the quaint and happy conceit of these arms and motto is that for every fish which goes up the river to spawn two return to the sea. A salmon on its back figures in the arms of the city of Glasgow, and also in the arms of Lumsden and Finlay, whilst other instances of salmon occur in the arms of Blackett-Ord, Sprot, and Winlaw.

The Herring occurs in the arms of Maconochie, the Roach in the arms of Roche ["Gules, three roaches naiant within a bordure engrailed argent. Crest: a rock, thereon a stork close, charged on the breast with a torteau, and holding in his dexter claw a roach proper"], and Trout in the arms of Troutbeck ["Azure, three trout fretted tête à la queue argent"]. The same arrangement of three fish occurs upon the seal of Anstruther Wester, but this design unfortunately has never been matriculated as a coat of arms.

The arms of Iceland present a curious charge, which is included upon the Royal shield of Denmark. The coat in question is: "Gules, a stockfish argent, crowned with an open crown or." The stockfish is a dried and cured cod, split open and with the head removed.

A Pike or Jack is more often termed a "lucy" in English heraldry and a "ged" in Scottish. Under its various names it occurs in the arms of Lucy, Lucas, Geddes, and Pyke.

The Eel is sometimes met with, as in the arms of Ellis, and though, as Woodward states, it is always given a wavy form, the term "ondoyant," which he uses to express this, has, I believe, no place in an English armorist's dictionary.

The Lobster and Crab are not unknown to English armory, being respectively the crests of the families of Dykes and Bridger. The arms of Bridger are: "Argent, a chevron engrailed sable, between three crabs gules." Lobster claws are a charge upon the arms of Platt-Higgins.

The arms of Birt are given in Papworth as: "Azure, a birthfish proper," and of Bersich as: "Argent, a perch azure." The arms of Cobbe (Bart., extinct) are: "Per chevron gules and sable, in chief two swans respecting and in base a herring cob naiant proper." The arms of Bishop Robinson of Carlisle were: "Azure, a flying fish in bend argent, on a chief of the second, a rose gules between two torteaux," and the crest of Sir Philip Oakley Fysh is: "On a wreath of the colours, issuant from a wreath of red coral, a cubit arm vested azure, cuffed argent, holding in the hand a flying fish proper." The coat of arms of Colston of Essex is: "Azure, two barbels hauriant respecting each other argent," and a barbel occurs in the crest of Binney. "Vert, three sea-breams or hakes hauriant argent" is the coat of arms attributed to a family of Dox or Doxey, and "Or, three chabots gules" is that of a French family of the name of Chabot. "Barry wavy of six argent and gules, three crevices (crayfish) two and one or" is the coat of Atwater. Codfish occur in the arms of Beck, dogfish in the arms of Dodds (which may, however, be merely the sea-dog of the Dodge achievement), flounders or flukes in the arms of Arbutt, garvinfishes in the arms of Garvey, and gudgeon in the arms of Gobion. Papworth also includes instances of mackerel, prawns, shrimps, soles, sparlings, sturgeon, sea-urchins, turbots, whales, and whelks. The whelk shell (Fig. 482) appears in the arms of Storey and Wilkinson.

CHAPTER XVI

REPTILES

If armorial zoology is "shaky" in its classification of and dealings with fish, it is most wonderful when its laws and selections are considered under the heading of reptiles. But with the exception of serpents (of various kinds), the remainder must have no more than a passing mention.

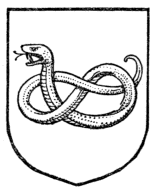

The usual heraldic Serpent is most frequently found "nowed," that is, interlaced in a knot (Fig. 483). There is a certain well-understood form for the interlacing which is always officially adhered to, but of late there has manifested itself amongst heraldic artists a desire to break loose to a certain extent from the stereotyped form. A serpent will sometimes be found "erect" and occasionally gliding or "glissant," and sometimes it will be met with in a circle with its tail in its mouth—the ancient symbol of eternity. Its constant appearance in British armory is due to the fact that it is symbolically accepted as the sign of medicine, and many grants of arms made to doctors and physicians introduce in some way either the serpent or the rod of Æsculapius, or a serpent entwined round a staff. A serpent embowed biting its tail occurs in the arms of Falconer, and a serpent on its back in the crest of Backhouse. Save for the matter of position, the serpent of British armory is always drawn in a very naturalistic manner. It is otherwise, however, in Continental armory, where the serpent takes up a position closely allied to that of our dragon. It is even sometimes found winged, and the arms of the family of Visconti, which subsequently came into use as the arms of the Duchy of Milan (Fig. 484), have familiarised us as far as Continental armory is concerned with a form of serpent which is very different from the real animal or from our own heraldic variety. Another instance of a serpent will be found in the arms of the Irish family of Cotter, which are: "Argent, a chevron gules between three serpents proper," and the family of Lanigan O'Keefe bear in one quarter of their shield: "Vert, three lizards in pale or." The family of Cole bear: "Argent, a chevron gules between three scorpions reversed sable," a coat of arms which is sometimes quoted with the chevron and the scorpions both gules or both sable. The family of Preed of Shropshire bear: "Azure, three horse-leeches;" and the family of Whitby bear: "Gules, three snakes coiled or; on a chief of the second, as many pheons sable." A family of Sutton bears: "Or, a newt vert, in chief a lion rampant gules all within a bordure of the last," and Papworth mentions a coat of arms for the name of Ory: "Azure, a chameleon on a shady ground proper, in chief a sun or." Another coat mentioned by Papworth is the arms of Bume: "Gules, a stellion serpent proper," though what the creature may be it is impossible to imagine. Unfortunately, when one comes to examine so many of these curious coats of arms, one finds no evidence that such families existed, or that there is no official authority or record of the arms to which reference can be made. There can be no doubt that they largely consist of misreadings or misinterpretations of both names and charges, and I am sorely afraid this remark is the true explanation of what otherwise would be most strange and interesting curiosities of arms. Sir Walter Scott's little story in "Quentin Durward" of Toison d'Or, who depicted the "cat looking through the dairy window" as the arms of Childebert, and blazoned it "sable a musion passant or, oppressed with a trellis gules, cloué of the second," gives in very truth the real origin of many quaint coats of arms and heraldic terms. Ancient heraldic writers seem to have amused themselves by inventing "appropriate" arms for mythological or historical personages, and I verily believe that when so doing they never intended these arms to stand for more than examples of their own wit. Their credulous successors incorporated these little witticisms in the rolls of arms they collected, and one can only hope that in the distant future the charming drawings of Mr. E. T. Reed which in recent years have appeared in Punch may not be used in like manner.

There are but few instances in English armory in which the Toad or Frog is met with. In fact, the only instance which one can recollect is the coat of arms attributed to a family of Botreaux, who are said to have borne: "Argent, three toads erect sable." I am confident, however, that this coat of arms, if it ever existed, and if it could be traced to its earliest sources, would be found to be really three buckets of water, a canting allusion to the name. Toads of course are the charges on the mythical arms of Pharamond.

Fig. 484.—Arms of the Visconti, Dukes of Milan: Argent, a serpent azure, devouring a child gules. (A wood-carving from the castle of Passau at the turn of the fifteenth century.)

Amongst the few instances I have come across of a snail in British armory are the crest of Slack of Derwent Hill ("in front of a crescent or, a snail proper") and the coat attributed by Papworth to the family of Bartan or Bertane, who are mentioned as bearing, "Gules, three snails argent in their shells or." This coat, however, is not matriculated in Scotland, so that one cannot be certain that it was ever borne. The snail occurs, however, as the crest of a family named Billers, and is also attributed to several other families as a crest.

Lizards appear occasionally in heraldry, though more frequently in Irish than English or Scottish coats of arms. A lizard forms part of the crest of Sillifant, and a hand grasping a lizard is the crest of M‘Carthy, and "Azure, three lizards or" the first quarter of the arms of an Irish family of the name of Cotter, who, however, blazon these charges upon their shield as evetts. The family of Enys, who bear: "Argent, three wyverns volant in pale vert," probably derive their arms from some such source.

CHAPTER XVII

INSECTS

The insect which is most usually met with in heraldry is undoubtedly the Bee. Being considered, as it is, the symbol of industry, small wonder that it has been so frequently adopted. It is usually represented as if displayed upon the shield, and it is then termed volant, though of course the real term which will sometimes be found used is "volant en arrière" (Fig. 485). It occurs in the arms of Dore, Beatson, Abercromby, Samuel, and Sewell, either as a charge or as a crest. Its use, however, as a crest is slightly more varied, inasmuch as it is found walking in profile, and with its wings elevated, and also perched upon a thistle as in the arms of Ferguson. A bee-hive "with bees diversely volant" occurs in the arms of Rowe, and the popularity of the bee in British armory is doubtless due to the frequent desire to perpetuate the fact that the foundation of a house has been laid by business industry. The fact that the bee was adopted as a badge by the Emperor Napoleon gave it considerable importance in French armory, inasmuch as he assumed it for his own badge, and the mantle and pavilion around the armorial bearings of the Empire were semé of these insects. They also appeared upon his own coronation mantle. He adopted them under the impression, which may or may not be correct, that they had at one time been the badge of Childeric, father of Clovis. The whole story connected with their assumption by Napoleon has been a matter of much controversy, and little purpose would be served by going into the matter here, but it may be added that Napoleon changed the fleur-de-lis upon the chief in the arms of Paris to golden bees upon a chief of gules, and a chief azure, semé of bees or, was added as indicative of their rank to the arms of "Princes-Grand-Dignitaries of the Empire." A bee-hive occurs as the crest of a family named Gwatkin, and also upon the arms of the family of Kettle of Wolverhampton.

The Grasshopper is most familiar as the crest of the family of Gresham, and this is the origin of the golden grasshoppers which are so constantly met with in the city of London. "Argent, a chevron sable between three grasshoppers vert" is the coat of arms of Woodward of Kent. Two of them figure in the arms of Treacher, which arms are now quartered by Bowles.

Ants are but seldom met with. "Argent, six ants, three, two, and one sable," is a coat given by Papworth to a family of the name of Tregent; "Vert, an ant argent," to Kendiffe; and "Argent, a chevron vert between three beetles proper" are the arms attributed by the same authority to a family named Muschamp. There can be little doubt, however, that these "beetles" should be described as flies.

Butterflies figure in the arms of Papillon ["Azure, a chevron between three butterflies volant argent"] and in the arms of Penhellicke ["Sable, three butterflies volant argent"].

Gadflies are to be found in a coat of arms for the name of Adams ["Per pale argent and gules, a chevron between three gadflies counterchanged"], and also in the arms of Somerscales, quartered by Skeet of Bishop Stortford. "Sable, a hornet argent" is one blazon for the arms of Bollord or Bolloure, but elsewhere the same coat is blazoned: "Sable, a harvest-fly in pale volant en arrière argent." Harvest flies were the charges on the arms of the late Sir Edward Watkin, Bart.

Crickets appear in the arms ["azure, a fire chest argent, flames proper, between three crickets or"] recently granted to Sir George Anderson Critchett, Bart.

The arms of Bassano (really of foreign origin and not an English coat) are: "Per chevron vert and argent, in chief three silkworm flies palewise en arrière, and in base a mulberry branch all counterchanged." "Per pale gules and azure, three stag-beetles, wings extended or," is assigned by Papworth to the Cornish family of Dore, but elsewhere these charges (under the same family name) are quoted as bees, gadflies, and flies. "Or, three spiders azure" is quoted as a coat for Chettle. A spider also figures as a charge on the arms of Macara. The crest of Thorndyke of Great Carleton, Lincolnshire, is: "On a wreath of the colours a damask rose proper, leaves and thorns vert, at the bottom of the shield a beetle or scarabæus proper."

Woodward, in concluding his chapter upon insects, quotes the arms of the family of Pullici of Verona, viz.: "Or, semé of fleas sable, two bends gules, surmounted by two bends sinister of the same."

CHAPTER XVIII

TREES, LEAVES, FRUITS, AND FLOWERS

The vegetable kingdom plays an important part in heraldry. Trees will be found of all varieties and in all numbers, and though little difference is made in the appearance of many varieties when they are heraldically depicted, for canting purposes the various names are carefully preserved. When, however, no name is specified, they are generally drawn after the fashion of oak-trees.

When a tree issues from the ground it will usually be blazoned "issuant from a mount vert," but when the roots are shown it is termed "eradicated."

A Hurst of Trees figures both on the shield and in the crest of France-Hayhurst, and in the arms of Lord Lismore ["Argent, in base a mount vert, on the dexter side a hurst of oak-trees, therefrom issuing a wolf passant towards the sinister, all proper"]. A hurst of elm-trees very properly is the crest of the family of Elmhurst. Under the description of a forest, a number of trees figure in the arms of Forrest.

The arms of Walkinshaw of that Ilk are: "Argent, a grove of fir-trees proper," and Walkinshaw of Barrowfield and Walkinshaw of London have matriculated more or less similar arms.

The Oak-Tree (Fig. 486) is of course the tree most frequently met with. Perhaps the most famous coat in which it occurs will be found in the arms granted to Colonel Carlos, to commemorate his risky sojourn with King Charles in the oak-tree at Boscobel, after the King's flight subsequent to the ill-fated battle of Worcester. The coat was: "Or, on a mount in base vert, an oak-tree proper, fructed or, surmounted by a fess gules, charged with three imperial crowns of the third" (Plate II.).

Fir-Trees will be found in the arms of Greg, Melles, De la Ferté, and Farquharson.

A Cedar-Tree occurs in the arms of Montefiore ["Argent, a cedar-tree, between two mounts of flowers proper, on a chief azure, a dagger erect proper, pommel and hilt or, between two mullets of six points gold"], and a hawthorn-tree in the arms of MacMurrogh-Murphy, Thornton, and in the crest of Kynnersley.

A Maple-Tree figures in the arms of Lord Mount-Stephen ["Or, on a mount vert, a maple-tree proper, in chief two fleurs-de-lis azure"], and in the crest of Lord Strathcona ["On a mount vert, a maple-tree, at the base thereof a beaver gnawing the trunk all proper"].

A Cocoanut-Tree is the principal charge in the arms of Glasgow (now Robertson-Glasgow) of Montgrennan, matriculated in 1807 ["Argent, a cocoanut-tree fructed proper, growing out of a mount in base vert, on a chief azure, a shakefork between a martlet on the dexter and a salmon on the sinister argent, the last holding in the mouth a ring or"].

The arms of Clifford afford an instance of a Coffee-Tree, and the coat of Chambers has a negro cutting down a Sugar-Cane.

A Palm-Tree occurs in the arms of Besant and in the armorials of many other families. The crest of Grimké-Drayton affords an instance of the use of palmetto-trees. An Olive-Tree is the crest of Tancred, and a Laurel-Tree occurs in the crest of Somers.

Cypress-Trees are quoted by Papworth in the arms of Birkin, probably an error for birch-trees, but the cypress does occur in the arms of Tardy, Comte de Montravel ["Argent, three cypress-trees eradicated vert, on a chief gules, as many bezants"], and "Or, a willow (salix) proper" is the coat of the Counts de Salis (now Fane-de-Salis).

The arms of Sweetland, granted in 1808, are: "Argent, on a mount vert, an orange-tree fructed proper, on a chief embattled gules, three roses of the field, barbed and seeded also proper."

A Mountain-Ash figures in the shield and crest of Wigan, and a Walnut-Tree is the crest of Waller, of Groombridge ["On a mount vert, a walnut-tree proper, on the sinister side an escutcheon pendent, charged with the arms of France, and thereupon a label of three points argent."]

The arms of Arkwright afford an example of a Cotton-Tree.

The curious crest of Sir John Leman, Lord Mayor of London, affords an instance of a Lemon-Tree ["In a lemon-tree proper, a pelican in her piety proper"].

The arms of a family whose name appears to have been variously spelled Estwere, Estwrey, Estewer, Estower, and Esture, have: "Upon an argent field a tree proper," variously described as an apple-tree, an ash-tree, and a cherry-tree. The probabilities largely point to its being an ash-tree. "Or, on a mount in base vert, a pear-tree fructed proper" is the coat of arms of Pyrton or Peryton, and the arms granted in 1591 to Dr. Lopus, a physician to Queen Elizabeth, were: "Or, a pomegranate-tree eradicated vert, fructed gold, supported by a hart rampant proper, crowned and attired of the first."

A Poplar Tree occurs in the arms of Gandolfi, but probably the prime curiosity must be the coat of Abank, which Papworth gives as: "Argent, a China-cokar tree vert." Its botanical identity remains a mystery.

Trunks of Trees for some curious reason play a prominent part in heraldry. The arms of Borough, of Chetwynd Park, granted in 1702, are: "Argent, on a mount in base, in base the trunk of an oak-tree sprouting out two branches proper, with the shield of Pallas hanging thereon or, fastened by a belt gules," and the arms of Houldsworth (1868) of Gonaldston, co. Notts, are: "Ermine, the trunk of a tree in bend raguly eradicated at the base proper, between three foxes' heads, two in chief and one in base erased gules."

But it is as a crest that this figure of the withered trunk sprouting again is most often met with, it being assigned to no less than forty-three families.

In England again, by one of those curious fads by which certain objects were repeated over and over again in the wretched designs granted by the late Sir Albert Woods, Garter, in spite of their unsuitability, tree-trunks fesswise eradicated and sprouting are constantly met with either as the basis of the crest or placed "in front of it" to help in providing the differences and distinctions which he insisted upon in a new grant. An example of such use of it will be found in the arms of the town of Abergavenny.

Stocks of Trees "couped and eradicated" are by no means uncommon. They figure in the arms of the Borough of Woodstock: "Gules, the stump of a tree couped and eradicated argent, and in chief three stags' heads caboshed of the same, all within a bordure of the last charged with eight oak-leaves vert." They also occur in the arms of Grove, of Shenston Park, co. Stafford, and in the arms of Stubbs.

The arms matriculated in Lyon Register by Capt. Peter Winchester (c. 1672-7) are: "Argent, a vine growing out of the base, leaved and fructed, between two papingoes endorsed feeding upon the clusters all proper." The vine also appears in the arms of Ruspoli, and the family of Archer-Houblon bear for the latter name: "Argent, on a mount in base, three hop-poles erect with hop-vines all proper."

The town of St. Ives (Cornwall) has no authorised arms, but those usually attributed to the town are: "Argent, an ivy branch overspreading the whole field vert."

"Gules, a flaming bush on the top of a mount proper, between three lions rampant argent, in the flanks two roses of the last" is the coat of Brander (now Dunbar-Brander) of Pitgavenny. Holly-bushes are also met with, as in the crests of Daubeney and Crackanthorpe, and a rose-bush as in the crest of Inverarity.

The arms of Owen, co. Pembroke, are: "Gules, a boar argent, armed, bristled, collared, and chained or to a holly-bush on a mount in base both proper."

A Fern-Brake is another stock object used in designing modern crests, and will be found in the cases of Harter, Scott-Gatty, and Lloyd.

Branches are constantly occurring, but they are usually oak, laurel, palm, or holly. They need to be distinguished from "slips," which are much smaller and with fewer leaves. Definite rules of distinction between e.g. an acorn "slipped," a slip of oak, and an oak-branch have been laid down by purists, but no such minute detail is officially observed, and it seems better to leave the point to general artistic discretion; the colloquial difference between a slip and a branch being quite a sufficient guide upon the point.

An example of an Oak-Branch occurs in the arms of Aikman, and another, which is rather curious, is the crest of Accrington.[21]

Oak-Slips, on the other hand, occur in the arms of Baldwin.

A Palm-Branch occurs in the crests of Innes, Chafy, and Corfield.

Laurel-Branches occur in the arms of Cooper, and sprigs of laurel in the arms of Meeking.

Holly-Branches are chiefly found in the arms of families named Irvine or Irwin, but they are invariably blazoned as "sheaves" of holly or as holly-branches of three leaves. To a certain extent this is a misnomer, because the so-called "branch" is merely three holly-leaves tied together.

"Argent, an almond-slip proper" is the coat of arms attributed to a family of Almond, and Papworth assigns "Argent, a barberry-branch fructed proper" to Berry.

"Argent, three sprigs of balm flowered proper" is stated to be the coat of a family named Balme, and "Argent, three teasels slipped proper" the coat of Bowden, whilst Boden of the Friary bears, "Argent, a chevron sable between three teasels proper, a bordure of the second." A teasle on a canton figures in the arms of Chichester-Constable.

The Company of Tobacco-Pipe Makers in London, incorporated in the year 1663, bore: "Argent, on a mount in base vert, three plants of tobacco growing and flowering all proper." The crest recently granted to Sir Thomas Lipton, Bart. ["On a wreath of the colours, two arms in saltire, the dexter surmounted by the sinister holding a sprig of the tea-plant erect, and the other a like sprig of the coffee-plant both slipped and leaved proper, vested above the elbow argent"], affords an example of both the coffee-plant and the tea-plant, which have both assisted him so materially in piling up his immense fortune. "Or, three birch-twigs sable" is the coat of Birches, and "Or, a bunch of nettles vert" is the coat of Mallerby of Devonshire. The pun in the last case is apparent.

The Cotton-Plant figures in the arms of the towns of Darwen, Rochdale, and Nelson, and two culms of the papyrus plant occur in the arms of the town of Bury.

The Coffee-Plant also figures in the arms of Yockney: "Azure, a chevron or, between a ship under sail in chief proper, and a sprig of the coffee-plant slipped in base of the second."

A branch, slip, bush, or tree is termed "fructed" when the fruit is shown, though the term is usually disregarded unless "fructed" of a different colour. When represented as "fructed," the fruit is usually drawn out of all proportion to its relative size.

Leaves are not infrequent in their appearance. Holly-leaves occur in the various coats for most people of the name of Irwin and Irvine, as already mentioned. Laurel-leaves occur in the arms of Leveson-Gower, Foulis, and Foulds.

Oak-Leaves occur in the arms of Trelawney ["Argent, a chevron sable, between three oak-leaves slipped proper"]; and hazel-leaves in the arms of Hesilrige or Hazlerigg ["Argent, a chevron sable, between three hazel-leaves vert].

"Argent, three edock (dock or burdock) leaves vert" is the coat of Hepburn. Papworth assigns "Argent, an aspen leaf proper" to Aspinal, and "Or, a betony-leaf proper" to Betty. "Argent, three aspen-leaves" is an unauthorised coat used by Espin, and the same coat with varying tinctures is assigned to Cogan. Killach is stated to bear: "Azure, three bay-leaves argent," and to Woodward, of Little Walsingham, Norfolk, was granted in 1806: "Vert, three mulberry-leaves or."

The Maple-Leaf has been generally adopted as a Canadian emblem, and consequently figures upon the arms of that Dominion, and in the arms of many families which have or have had Canadian associations.

"Vert, three vine-leaves or" is assigned by Papworth to Wortford, and the same authority mentions coats in which woodbine-leaves occur for Browne, Theme, and Gamboa. Rose-leaves occur in the arms of Utermarck, and walnut-leaves figure in the arms of Waller.

A curious leaf—usually called the "sea-leaf," which is properly the "nenuphar-leaf," is often met with in German heraldry, as are Linden leaves.

Although theoretically leaves, the trefoil, quatrefoil, and cinquefoil are a class by themselves, having a recognised heraldic status as exclusively heraldic charges, and the quatrefoil and cinquefoil, in spite of the derivation of their names, are as likely to have been originally flowers as leaves.

The heraldic Trefoil (Fig. 487), though frequently specifically described as "slipped," is nevertheless always so depicted, and it is not necessary to so describe it. Of late a tendency has been noticeable in paintings from Ulster's Office to represent the trefoil in a way more nearly approaching the Irish shamrock, from which it has undoubtedly been derived. Instances of the trefoil occur in the arms of Rodd, Dobrée, MacDermott, and Gilmour. The crowned trefoil is one of the national badges of Ireland.

A four-leaved "lucky" shamrock has been introduced into the arms of Sir Robert Hart, Bart.

The Quatrefoil (Fig. 488) is not often met with, but it occurs in the arms of Eyre, King, and Dreyer.

The Cinquefoil (Fig. 489) is of frequent appearance, but, save in exceedingly rare instances, neither the quatrefoil nor the cinquefoil will be met with "slipped." The constant occurrence of the cinquefoil in early rolls of arms is out of all proportion to its distinctiveness or artistic beauty, and the frequency with which it is met with in conjunction with the cross crosslet points clearly to the fact that there is some allusion behind, if this could only be fathomed. Many a man might adopt a lion through independent choice, but one would not expect independent choice to lead so many to pitch upon a combination of cross crosslets and cinquefoils. The cross crosslets, I am confident, are a later addition in many cases, for the original arms of D'Arcy, for example, were simply: "Argent, three cinquefoils gules." The arms of the town of Leicester are: "Gules, a cinquefoil ermine," and this is the coat attributed to the family of the De Beaumonts or De Bellomonts, Earls of Leicester. Simon de Montfort, the great Earl of Leicester, was the son or grandson of Amicia, a coheir of the former Earls, and as such entitled to quarter the arms of the De Bellomonts. As stated on page 117 (vide Figs. 97 and 98), there are two coats attributed to De Montfort. His only status in this country depended solely upon the De Bellomont inheritance, and, conformably with the custom of the period, we are far more likely to find him using arms of De Bellomont or De Beaumont than of Montfort. From the similarity of the charge to the better-known Beaumont arms, I am inclined to think the lion rampant to be the real De Bellomont coat. The origin of the cinquefoil has yet to be accounted for. The earliest De Bellomont for whom I can find proof of user thereof is Robert "Fitz-Pernell," otherwise De Bellomont, who died in 1206, and whose seal (Fig. 490) shows it. Be it noted it is not on a shield, and though of course this is not proof in any way, it is in accord with my suggestion that it is nothing more than a pimpernel flower adopted as a device or badge to typify his own name and his mother's name, she being Pernelle or Petronilla, the heiress of Grantmesnil. The cinquefoil was not the coat of Grantmesnil but a quaint little conceit, and is not therefore likely to have been used as a coat of arms by the De Bellomonts, though no doubt they used it as a badge and device, as no doubt did Simon de Montfort. Simon de Montfort split England into two parties. Men were for Montfort or the king, and those that were for De Montfort very probably took and used his badge of a cinquefoil as a party badge.