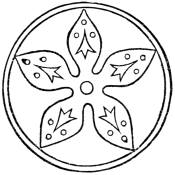

The cinquefoil in its ordinary heraldic form also occurs in the arms of Umfraville, Bardolph, Hamilton, and D'Arcy, and sprigs of cinquefoil will be found in the arms of Hill, and in the crest of Kersey. The cinquefoil is sometimes found pierced. The five-foiled flower being the blossom of so many plants, what are to all intents and purposes cinquefoils occur in the arms of Fraser, where they are termed "fraises," of Primrose, where they are blazoned "primroses," and of Lambert, where they are called "narcissus flowers."

The double Quatrefoil is cited as the English difference mark for the ninth son, but as these difference marks are but seldom used, and as ninth sons are somewhat of a rarity, it is seldom indeed that this particular mark is seen in use. Personally I have never seen it.

The Turnip makes an early appearance in armory, and occurs in the coat of Dammant ["Sable, a turnip leaved proper, a chief or, gutté-de-poix"].

The curious crest of Lingen, which is "Seven leeks root upwards issuing from a ducal coronet all proper," is worthy of especial mention.

In considering flowers as a charge, a start must naturally be made with the rose, which figures so prominently in the heraldry of England.

The heraldic Rose until a much later date than its first appearance in armory—it occurs, however, at the earliest period—was always represented in what we now term the "conventional" form, with five displayed petals (Fig. 491). Accustomed as we are to the more ornate form of the cultivated rose of the garden, those who speak of the "conventional" heraldic rose rather seem to overlook that it is an exact reproduction of the wild rose of the hedgerow, which, morever, has a tendency to show itself "displayed" and not in the more profile attitude we are perhaps accustomed to. It should also be observed that the earliest representations of the heraldic rose depict the intervening spaces between the petals which are noticeable in the wild rose. Under the Tudor sovereigns, the heraldic rose often shows a double row of petals, a fact which is doubtless accounted for by the then increasing familiarity with the cultivated variety, and also by the attempt to conjoin the rival emblems of the warring factions of York and Lancaster.

Though the heraldic rose is seldom, if ever, otherwise depicted, it should be described as "barbed vert" and "seeded or" (or "barbed and seeded proper") when the centre seeds and the small intervening green leaves (the calyx) between the petals are represented in their natural colours. In the reign of the later Tudor sovereigns the conventionality of earlier heraldic art was slowly beginning to give way to the pure naturalism towards which heraldic art thereafter steadily degenerated, and we find that the rose then begins (both as a Royal badge and elsewhere) to be met with "slipped and leaved" (Fig. 492). The Royal fleurs-de-lis are turned into natural lilies in the grant of arms to Eton College, and in the grant to William Cope, Cofferer to Henry VII., the roses are slipped ["Argent, on a chevron azure, between three roses gules, slipped and leaved vert, as many fleurs-de-lis or. Crest: out of a fleur-de-lis or, a dragon's head gules"]. A rose when "slipped" theoretically has only a stalk added, but in practice it will always have at least one leaf added to the slip, and a rose "slipped and leaved" would have a leaf on either side. A rose "stalked and leaved" is not so limited, and will usually be found with a slightly longer stalk and several leaves; but these technical refinements of blazon, which are really unnecessary, are not greatly observed or taken into account. The arms of the Burgh of Montrose afford an example of a single rose as the only charge, although other instances will be met with in the arms of Boscawen, Viscount Falmouth ["Ermine, a rose gules, barbed and seeded proper"], and of Nightingale, Bart. ["Per pale ermine and gules, a rose counterchanged"].

Amongst the scores of English arms in which the rose figures, it will be found in the original heraldic form in the case of the arms of Southampton (Plate VII.); and either stalked or slipped in the arms of Brodribb and White-Thomson. A curious instance of the use of the rose will be found in the crest of Bewley, and the "cultivated" rose was depicted in the emblazonment of the crest of Inverarity, which is a rose-bush proper.

Heraldry, with its roses, has accomplished what horticulture has not. There is an old legend that when Henry VII. succeeded to the English throne some enterprising individual produced a natural parti-coloured rose which answered to the conjoined heraldic rose of gules and argent. Our roses "or" may really find their natural counterpart in the primrose, but the arms of Rochefort ["Quarterly or and azure, four roses counterchanged"] give us the blue rose, the arms of Berendon ["Argent, three roses sable"] give us the black rose, and the coat of Smallshaw ["Argent, a rose vert, between three shakeforks sable"] is the long-desired green rose.

The Thistle (Fig. 493) ranks next to the rose in British heraldic importance. Like the rose, the reason of its assumption as a national badge remains largely a matter of mystery, though it is of nothing like so ancient an origin. Of course one knows the time-honoured and wholly impossible legend that its adoption as a national symbol dates from the battle of Largs, when one of the Danish invaders gave away an attempted surprise by his cry of agony caused by stepping barefooted upon a thistle.

The fact, however, remains that its earliest appearance is on the silver coinage of 1474, in the reign of James III., but during that reign there can be no doubt that it was accepted either as a national badge or else as the personal badge of the sovereign. The period in question was that in which badges were so largely used, and it is not unlikely that, desiring to vie with his brother of England, and fired by the example of the broom badge and the rose badge, the Scottish king, remembering the ancient legend, chose the thistle as his own badge. In 1540, when the thistle had become recognised as one of the national emblems of the kingdom, the foundation of the Order of the Thistle stereotyped the fact for all future time. The conventional heraldic representation of the thistle is as it appears upon the star of that Order, that is, the flowered head upon a short stalk with a leaf on either side. Though sometimes represented of gold, it is nearly always proper. It has frequently been granted as an augmentation, though in such a meaning it will usually be found crowned. The coat of augmentation carried in the first quarter of his arms by Lord Torphichen is: "Argent, a thistle vert, flowered gules (really a thistle proper), on a chief azure an imperial crown or." "Sable, a thistle (possibly really a teasel) or, between three pheons argent" is the coat of Teesdale, and "Gules, three thistles or" is attributed in Papworth to Hawkey. A curious use of the thistle occurs in the arms of the National Bank of Scotland (granted 1826), which are: "Or, the image of St. Andrew with vesture vert, and surcoat purpure, bearing before him the cross of his martyrdom argent, all resting on a base of the second, in the dexter flank a garb gules, in the sinister a ship in full sail sable, the shield surrounded with two thistles proper disposed in orle."

The Lily in its natural form sometimes occurs, though of course it generally figures as the fleur-de-lis, which will presently be considered. The natural lily will be found in the arms of Aberdeen University, of Dundee, and in the crests of various families of the name of Chadwick. It also occurs in the arms of the College of St. Mary the Virgin, at Eton ["Sable, three lilies argent, on a chief per pale azure and gules a fleur-de-lis on the dexter side, and a lion passant guardant or on the sinister"]. Here they doubtless typify the Virgin, to whom they have reference; as also in the case of Marylebone (Fig. 252).

The arms of Lilly, of Stoke Prior, are: "Gules, three lilies slipped argent;" and the arms of J. E. Lilley, Esq., of Harrow, are: "Azure, on a pile between two fleurs-de-lis argent, a lily of the valley eradicated proper. Crest: on a wreath of the colours, a cubit arm erect proper, charged with a fleur-de-lis argent and holding in the hand two lilies of the valley, leaved and slipped in saltire, also proper."

Columbine Flowers occur in the arms of Cadman, and Gillyflowers in the arms of Livingstone. Fraises—really the flowers of the strawberry-plant—occur, as has been already mentioned, in the arms of Fraser, and Narcissus Flowers in the arms of Lambeth. "Gules, three poppy bolles on their stalks in fess or" are the arms of Boller.

The Lotus-Flower, which is now very generally becoming the recognised emblem of India, is constantly met with in the arms granted to those who have won fortune or reputation in that country. Instances in which it occurs are the arms of Sir Roper Lethbridge, K.C.I.E., Sir Thomas Seccombe, G.C.I.E., and the University of Madras.

The Sylphium-Plant occurs in the arms of General Sir Henry Augustus Smyth, K.C.M.G., which are: Vert, a chevron erminois, charged with a chevron gules, between three Saracens' heads habited in profile couped at the neck proper, and for augmentation a chief argent, thereon a mount vert inscribed with the Greek letters K Y P A gold and issuant therefrom a representation of the plant Silphium proper. Crests: 1. (of augmentation) on a wreath of the colours, a mount vert inscribed with the aforesaid Greek letters and issuant therefrom the Silphium as in the arms; 2. on a wreath of the colours, an anchor fesswise sable, thereon an ostrich erminois holding in the beak a horse-shoe or. Motto: "Vincere est vivere."

The arms granted to Sir Richard Quain were: "Argent, a chevron engrailed azure, in chief two fers-de-moline gules, and issuant from the base a rock covered with daisies proper."

Primroses occur (as was only to be expected) in the arms of the Earl of Rosebery ["Vert, three primroses within a double tressure flory counterflory or"].

The Sunflower or Marigold occurs in the crest of Buchan ["A sunflower in full bloom towards the sun in the dexter chief"], and also in the arms granted in 1614 to Florio. Here, however, the flower is termed a heliotrope. The arms in question are: "Azure, a heliotrope or, issuing from a stalk sprouting from two leaves vert, in chief the sun in splendour proper."

Tulips occur in the arms of Raphael, and the Cornflower or Bluebottle in the arms of Chorley of Chorley, Lancs. ["Argent, a chevron gules between three bluebottles slipped proper"], and also in the more modern arms of that town.

Saffron-Flowers are a charge upon the arms of Player of Nottingham. The arms granted to Sir Edgar Boehm, Bart., were: "Azure, in the sinister canton a sun issuant therefrom eleven rays, over all a clover-plant eradicated proper."

The Fleur-de-Lis.—Few figures have puzzled the antiquary so much as the fleur-de-lis. Countless origins have been suggested for it; we have even lately had the height of absurdity urged in a suggested phallic origin, which only rivals in ridiculousness the long since exploded legend that the fleurs-de-lis in the arms of France were a corrupted form of an earlier coat, "Azure, three toads or," the reputed coat of arms of Pharamond!

To France and the arms of France one must turn for the origin of the heraldic use of the fleur-de-lis. To begin with, the form of the fleur-de-lis as a mere presumably meaningless form of decoration is found long before the days of armory, in fact from the earliest period of decoration. It is such an essentially natural development of decoration that it may be accepted as such without any attempt to give it a meaning or any symbolism. Its earliest heraldic appearances as the finial of a sceptre or the decoration of a coronet need not have had any symbolical character.

We then find the "lily" accepted as having some symbolical reference to France, and it should be remembered that the iris was known by the name of a lily until comparatively modern times.

It is curious—though possibly in this case it may be only a coincidence—that, on a coin of the Emperor Hadrian, Gaul is typified by a female figure holding in the hand a lily, the legend being, "Restutori Galliæ." The fleur-de-lis as the finial of a sceptre and as an ornament of a crown can be taken back to the fifth century. Fleurs-de-lis upon crowns and coronets in France are at least as old as the reign of King Robert (son of Hugh Capet) whose seal represents him crowned in this manner.

We have, moreover, the ancient legendary tradition that at the baptism of Clovis, King of the Franks, the Virgin (whose emblem the lily has always been) sent a lily by an angel as a mark of her special favour. It is difficult to determine the exact date at which this tradition was invented, but its accepted character may be judged from the fact that it was solemnly advanced by the French bishops at the Council of Trent in a dispute as to the precedence of their sovereign. The old legend as to Clovis would naturally identify the flower with him, and it should be noted that the names Clovis, Lois, Loys, and Louis are identical. "Loys" was the signature of the kings of France until the time of Louis XIII. It is worth the passing conjecture that what are sometimes termed "Cleves lilies" may be a corrupted form of Clovis lilies. There can be little doubt that the term "fleur-de-lis" is quite as likely to be a corruption of "fleur-de-lois" as flower of the lily. The chief point is that the desire was to represent a flower in allusion to the old legend, without perhaps any very definite certainty of the flower intended to be represented. Philip I. on his seal (A.D. 1060) holds a short staff terminating in a fleur-de-lis. The same object occurs in the great seal of Louis VII. In the seal of his wife, Queen Constance, we find her represented as holding in either hand a similar object, though in these last cases it is by no means certain that the objects are not attempts to represent the natural flower. A signet of Louis VII. bears a single fleur-de-lis "florencée" (or flowered), and in his reign the heraldic fleur-de-lis undoubtedly became stereotyped as a symbolical device, for we find that when in the lifetime of Louis VII. his son Philip was crowned, the king prescribed that the prince should wear "ses chausses appelées sandales ou bottines de soye, couleur bleu azuré sémée en moult endroits de fleurs-de-lys or, puis aussi sa dalmatique de même couleur et œuvre." On the oval counter-seal of Philip II. (d. 1223) appears a heraldic fleur-de-lis. His great seal, as also that of Louis VIII., shows a seated figure crowned with an open crown of "fleurons," and holding in his right hand a flower, and in his left a sceptre surmounted by a heraldic fleur-de-lis enclosed within a lozenge-shaped frame. On the seal of Louis VIII. the conjunction of the essentially heraldic fleur-de-lis (within the lozenge-shaped head of the sceptre), and the more natural flower held in the hand, should leave little if any doubt of the intention to represent flowers in the French fleurs-de-lis. The figure held in the hand represents a flower of five petals. The upper pair turned inwards to touch the centre one, and the lower pair curved downwards, leave the figure with a marked resemblance both to the iris and to the conventional fleur-de-lis. The counter-seal of Louis VIII. shows a Norman-shaped shield semé of fleurs-de-lis of the conventional heraldic pattern. By then, of course, "Azure, semé-de-lis or" had become the fixed and determined arms of France. By an edict dated 1376, Charles V. reduced the number of fleurs-de-lis in his shield to three: "Pour symboliser la Sainte-Trinite."

The claim of Edward III. to the throne of France was made on the death of Charles IV. of France in 1328, but the decision being against him, he apparently acquiesced, and did homage to Philip of Valois (Philip VI.) for Guienne. Philip, however, lent assistance to David II. of Scotland against King Edward, who immediately renewed his claim to France, assumed the arms and the title of king of that country, and prepared for war. He commenced hostilities in 1339, and upon his new Great Seal (made in the early part of 1340) we find his arms represented upon shield, surcoat, and housings as: "Quarterly, 1 and 4, azure, semé-de-lis or (for France); 2 and 3, gules, three lions passant guardant in pale or (for England)." The Royal Arms thus remained until 1411, when upon the second Great Seal of Henry IV. the fleurs-de-lis in England (as in France) were reduced to three in number, and so remained as part of the Royal Arms of this country until the latter part of the reign of George III.

Fleurs-de-lis (probably intended as badges only) had figured upon all the Great Seals of Edward III. On the first seal (which with slight alterations had also served for both Edward I. and II.), a small fleur-de-lis appears over each of the castles which had previously figured on either side of the throne. In the second Great Seal, fleurs-de-lis took the places of the castles.

The similarity of the Montgomery arms to the Royal Arms of France has led to all kinds of wild genealogical conjectures, but at a time when the arms of France were hardly determinate, the seal of John de Mundegumbri is met with, bearing a single fleur-de-lis, the original from which the arms of Montgomery were developed. Letters of nobility and the name of Du Lis were granted by Charles VII. in December 1429 to the brothers of Joan of Arc, and the following arms were then assigned to them: "Azure, a sword in pale proper, hilted and supporting on its point an open crown or, between two fleurs-de-lis of the last."

The fleur-de-lis "florencée," or the "fleur-de-lis flowered," as it is termed in England, is officially considered a distinct charge from the simple fleur-de-lis. Eve employs the term "seeded," and remarks of it: "This being one of the numerous instances of pedantic, because unnecessary distinction, which showed marks of decadence; for both forms occur at the same period, and adorn the same object, evidently with the same intention." The difference between these forms really is that the fleur-de-lis is "seeded" when a stalk having seeds at the end issues in the upper interstices. In a fleur-de-lis "florencée," the natural flower of a lily issues instead of the seeded stalk. This figure formed the arms of the city of Florence.

Fleurs-de-lis, like all other Royal emblems, are frequently to be met with in the arms of towns, e.g. in the arms of Lancaster, Maryborough, Wakefield, and Great Torrington. The arms of Wareham afford an instance of fleurs-de-lis reversed, and the Corporate Seals of Liskeard and Tamworth merit reproduction, did space permit, from the designs of the fleurs-de-lis which there appear. One cannot leave the fleur-de-lis without referring to one curious development of it, viz. the leopard's face jessant-de-lis (Fig. 332), a curious charge which undoubtedly originated in the arms of the family of Cantelupe. This charge is not uncommon, though by no means so usual as the leopard's face. Planché considers that it was originally derived from the fleur-de-lis, the circular boss which in early representations so often figures as the centre of the fleur-de-lis, being merely decorated with the leopard's face. One can follow Planché a bit further by imagining that this face need not necessarily be that of a leopard, for at a certain period all decorative art was crowded with grotesque masks whenever opportunity offered. The leopard's face jessant-de-lis is now represented as a leopard's face with the lower part of a fleur-de-lis issuing from the mouth, and the upper part rising from behind the head. Instances of this charge occur as early as the thirteenth century as the arms of the Cantelupe family, and Thomas de Cantelupe having been Bishop of Hereford 1275 to 1282, the arms of that See have since been three leopards' faces jessant-de-lis, the distinction being that in the arms of the See of Hereford the leopards' faces are reversed.

The origin may perhaps make itself apparent when we remember that the earliest form of the name was Cantelowe. Is it not probable that "lions'" faces (i.e. head de leo) may have been suggested by the name? Possibly, however, wolf-heads may have been meant, suggested by lupus, or by the same analogy which gives us wolf-heads or wolves upon the arms of Low and Lowe.

Fruit—the remaining division of those charges which can be classed as belonging to the vegetable kingdom—must of necessity be but briefly dealt with.

Grapes perhaps cannot be easily distinguished from vines (to which refer, page 264), but the arms of Bradway of Potscliff, co. Gloucester ["Argent, a chevron gules between three bunches of grapes proper"] and of Viscountess Beaconsfield, the daughter of Captain John Viney Evans ["Argent, a bunch of grapes stalked and leaved proper, between two flaunches sable, each charged with a boar's head argent"] are instances in point.

Apples occur in the arms of Robert Applegarth (Edward III. Roll) ["Argent, three apples slipped gules"] and "Or, a chevron between three apples gules" is the coat of a family named Southbey.

Pears occur in the arms of Allcroft, of Stokesay Castle, Perrins, Perry, Perryman, and Pirie.

Oranges are but seldom met with in British heraldry, but an instance occurs in the arms of Lord Polwarth, who bears over the Hepburn quarterings an inescutcheon azure, an orange slipped and surmounted by an imperial crown all proper. This was an augmentation conferred by King William III., and a very similar augmentation (in the 1st and 4th quarters, azure, three oranges slipped proper within an orle of thistles or) was granted to Livingstone, Viscount Teviot.

The Pomegranate (Fig. 495), which dimidiated with a rose was one of the badges of Queen Mary, is not infrequently met with.

The Pineapple in heraldry is nearly always the fir-cone. In the arms of Perring, Bart. ["Argent, on a chevron engrailed sable between three pineapples (fir-cones) pendent vert, as many leopards' faces of the first. Crest: on a mount a pineapple (fir-cone) vert"], and in the crest of Parkyns, Bart. ["Out of a ducal coronet or, a pineapple proper"], and also in the arms of Pyne ["Gules, a chevron ermine between three pineapples or"] and Parkin-Moore, the fruit is the fir or pine cone. Latterly the likelihood of confusion has led to the general use of the term "pine-cone" in such cases, but the ancient description was certainly "pineapple." The arms of John Apperley, as given in the Edward III. Roll, are: "Argent, a chevron gules between three pineapples (fir-cones) vert, slipped or."

The real pineapple of the present day does, however, occur, e.g. in the arms of Benson, of Lutwyche, Shropshire ["Argent, on waves of the sea, an old English galley all proper, on a chief wavy azure a hand couped at the wrist, supporting on a dagger the scales of Justice between two pineapples erect or, leaved vert. Mantling azure and argent. Crest: upon a wreath of the colours, a horse caparisoned, passant, proper, on the breast a shield argent, charged with a pineapple proper. Motto: 'Leges arma tenent sanctas'"].

Bean-Pods occur in the arms of Rise of Trewardreva, co. Cornwall ["Argent, a chevron gules between three bean-pods vert"], and Papworth mentions in the arms of Messarney an instance of cherries ["Or, a chevron per pale gules and vert between three cherries of the second slipped of the third"]. Elsewhere, however, the charges on the shield of this family are termed apples. Strawberries occur in the arms and crest of Hollist, and the arms of Duffield are: "Sable, a chevron between three cloves or." The arms of the Grocers' Livery Company, granted in 1531-1532, are: "Argent, a chevron gules between nine cloves, three, three and three." The arms of Garwynton are stated to be: "Sable, a chevron between three heads of garlick pendent argent," but another version gives the charges as pomegranates. "Azure, a chevron between three gourds pendent, slipped or" is a coat attributed to Stukele, but here again there is uncertainty, as the charges are sometimes quoted as pears. The arms of Bonefeld are: "Azure, a chevron between three quinces or." The arms of Alderberry are naturally: "Argent, three branches of alder-berries proper." The arms of Haseley of Suffolk are: "Argent, a fess gules, between three hazel-nuts or, stalks and leaves vert." Papworth also mentions the arms of Tarsell, viz.: "Or, a chevron sable, between three hazel-nuts erect, slipped gules." It would, however, seem more probable that these charges are really teazles.

The fruit of the oak—the Acorn (Fig. 496)—has already been incidentally referred to, but other instances occur in the arms of Baldwin, Stable, and Huth.

Wheat and other grain is constantly met with in British armory. The arms of Bigland ["Azure, two ears of big wheat erect in fess and bladed or"] and of Cheape are examples, and others occur in the arms of Layland-Barratt, Cross, and Rye ["Gules, on a bend argent, between two ears of rye, stalked, leaved, and slipped or, three crosses cramponné sable"].

Garbs, as they are invariably termed heraldically, are sheaves, and are of very frequent occurrence. The earliest appearance of the garb (Fig. 497) in English heraldry is on the seal of Ranulph, Earl of Chester, who died in 1232. Garbs therefrom became identified with the Earldom of Chester, and subsequently "Azure, three garbs or" became and still remain the territorial or possibly the sovereign coat of that earldom. Garbs naturally figure, therefore, in the arms of many families who originally held land by feudal tenure under the Earls of Chester, e.g. the families of Cholmondeley ["Gules, in chief two helmets in profile argent, and in base a garb vert"] and Kevilioc ["Azure, six garbs, three, two, and one or"]. Grosvenor ["Azure, a garb or"] is usually quoted as another example, and possibly correctly, but a very interesting origin has been suggested by Mr. W. G. Taunton in his work "The Tauntons of Oxford, by One of Them":—

"I merely wish to make a few remarks of my own that seem to have escaped other writers on genealogical matters.

"In the first place, Sir Gilbert le Grosvenor, who is stated to have come over with William of Normandy at the Conquest, is described as nephew to Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester; but Hugh Lupus was himself nephew to King William. Now, William could not have been very old when he overthrew Harold at Hastings. It seems, therefore, rather improbable that Sir Gilbert le Grosvenor, who was his nephew's nephew, could actually have fought with him at Hastings, especially when William lived to reign for twenty-one years after, and was not very old when he died.

"The name Grosvenor does not occur in any of the versions of the Roll of Battle Abbey. Not that any of these versions of this celebrated Roll are considered authentic by modern critics, who say that many names were subsequently added by the monks to please ambitious parvenus. The name Venour is on the Roll, however, and it is just possible that this Venour was the Grosvenor of our quest. The addition of 'Gros' would then be subsequent to his fattening on the spoils of the Saxon and cultivating a corporation. 'Venour' means hunter, and 'Gros' means fat. Gilbert's uncle, Hugh Lupus, was, we know, a fat man; in fact, he was nicknamed 'Hugh the Fat.' The Grosvenors of that period probably inherited obesity from their relative, Hugh Lupus, therefore, and the fable that they were called Grosvenor on account of their office of 'Great Huntsman' to the Dukes of Normandy is not to be relied on.

"We are further on told by the old family historians that when Sir Robert Grosvenor lost the day in that ever-memorable controversy with Sir Richard le Scrope, Baron of Bolton, concerning the coat of arms—'Azure, a bend or'—borne by both families, Sir Robert Grosvenor took for his arms one of the garbs of his kinsman, the Earl of Chester.

"It did not seem to occur to these worthies that the Earl of Chester, who was their ancestor's uncle, never bore the garbs in his arms, but a wolf's head.

"It is true that one or two subsequent Earls of Chester bore garbs, but these Earls were far too distantly connected with the Grosvenors to render it likely that the latter would borrow their new arms from this source.

"It is curious that there should have been in this same county of Chester a family of almost identical name also bearing a garb in their arms, though their garb was surrounded by three bezants.

"The name of this family was Grasvenor, or Gravenor, and, moreover, the tinctures of their arms were identical with those of Grosvenor. It is far more likely, therefore, that the coat assumed by Sir Robert after the adverse decision of the Court of Chivalry was taken from that of Grasvenor, or Gravenor, and that the two families were known at that time to be of common origin, although their connection with each other has subsequently been lost.

"In French both gros and gras mean fat, and we have both forms in Grosvenor and Grasvenor.

"A chief huntsman to Royalty would have been Grandvenor, not Grosvenor or Grasvenor.

"All these criticisms of mine, however, only affect the origin of the arms, and not the ancient and almost Royal descent of this illustrious race. Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester, was a son of the Duke of Brittany, as is plainly stated in his epitaph.

"This connection of uncle and nephew, then, between 'Hugh the Fat' and Gilbert Grosvenor implies a maternal descent from the Dukes of Brittany for the first ancestor of the Grosvenor family.

"In virtue of their descent from an heiress of the house of Grosvenor, it is only necessary to add the Tauntons of Oxford are Grosvenors, heraldically speaking, and that quartering so many ancient coats through the Tanners and the Grosvenors with our brand-new grant is like putting old wine into new bottles.

"Hugh Lupus left no son to succeed him, and the subsequent descent of the Earldom of Chester was somewhat erratic. So I think there is some point in my arguments regarding the coat assumed by Sir Robert Grosvenor of Hulme."

Though a garb, unless quoted otherwise, is presumed to be a sheaf of wheat, the term is not so confined. The garbs in the arms of Comyn, which figure as a quartering in so many Scottish coats, are really of cummin, as presumably are the garbs in the arms of Cummins. When a garb is "banded" of a different colour this should be stated, and Elvin states that it may be "eared" of a different colour, though I confess I am aware of no such instance.

"Argent, two bundles of reeds in fess vert," is the coat of Janssen of Wimbledon, Surrey (Bart., extinct), and a bundle of rods occurs in the arms of Evans, and the crest of Harris, though in this latter case it is termed a faggot.

Reeds also occur in the crest of Reade, and the crest of Middlemore ["On a wreath of colours, a moorcock amidst grass and reeds proper"] furnishes another example.

Bulrushes occur in the crest of Billiat, and in the arms of Scott ["Argent, on a mount of bulrushes in base proper, a bull passant sable, a chief pean, billetté or"].

Grass is naturally presumed on the mounts vert which are so constantly met with, but more definite instances can be found in the arms of Sykes, Hulley, and Hill.

CHAPTER XIX

INANIMATE OBJECTS

In dealing with those charges which may be classed under the above description one can safely say that there is scarcely an object under the sun which has not at some time or other been introduced into a coat of arms or crest. One cannot usefully make a book on armory assume the character of a general encyclopædia of useful knowledge, and reference will only be made in this chapter to a limited number, including those which from frequent usage have obtained a recognised heraldic character. Mention may, at the outset, be made of certain letters of the alphabet. Instances of these are scarcely common, but the family of Kekitmore may be adduced as bearing "Gules, three S's or," while Bridlington Priory had for arms: "Per pale, sable and argent, three B's counterchanged." The arms of Rashleigh are: "Sable, a cross or, between in the first quarter a Cornish chough argent, beaked and legged gules; in the second a text T; in the third and fourth a crescent all argent." Corporate arms (in England) afford an instance of alphabetical letters in the case of the B's on the shield of Bermondsey.

The Anchor (Fig. 498).—This charge figures very largely in English armory, as may, perhaps, be looked for when it is remembered that maritime devices occur more frequently in sea-board lands than in continents. The arms of the town of Musselburgh are: "Azure, three anchors in pale, one in the chief and two in the flanks or, accompanied with as many mussels, one in the dexter and one in the sinister chief points, and the third in base proper." The Comtes de St. Cricq, with "Argent, two anchors in saltire sable, on a chief three mullets or," will be an instance in point as to France.

Anvils.—These are occasionally met with, as in the case of the arms of a family of the name of Walker, who bear: "Argent, on a chevron gules, between two anvils in chief and an anchor in base sable, a bee between two crescents or. Mantling gules and argent. Crest: upon a wreath of the colours, on a mount within a wreathed serpent a dove all statant proper."

Arches, castles, towers, and turrets may be exemplified, amongst others, by the following.

Instances of Castles and Towers will be found in the arms of Carlyon and Kelly, and of the former fractured castles will be found in the shield of Willoughby quartered by Bertie; while an example of a quadrangular castle may be seen in the arms of Rawson. The difference between a Castle (Fig. 499) and a Tower (Fig. 500) should be carefully noticed, and though it is a distinction but little observed in ancient days it is now always adhered to. When either castle or tower is surmounted by smaller towers (as Fig. 501) it is termed "triple-towered."

An instance of a Fortification as a charge occurs in the shield of Sconce: "Azure, a fortification (sconce) argent, masoned sable, in the dexter chief point a mullet of six points of the second."

Gabions were hampers filled with earth, and were used in the construction of fortifications and earthworks. They are of occasional occurrence in English armory at any rate, and may be seen in the shields of Christie and of Goodfellow.

The arms of Banks supply an instance of Arches. Mention may here perhaps be made of William Arches, who bore at the siege of Rouen: "Gules, three double arches argent." The family of Lethbridge bear a bridge, and this charge figures in a number of other coats.

An Abbey occurs in the arms of Maitland of Dundrennan ["Argent, the ruins of an old abbey on a piece of ground all proper"], and a monastery in that of McLarty ["Azure, the front of an ancient monastery argent"]. A somewhat isolated instance of a Temple occurs in the shield of Templer.

A curious canting grant of arms may be seen in that to the town of Eccles, in which the charge is an Ecclesiastical Building, and similar though somewhat unusual charges figure also in the quartering for Chappel ["Per chevron or and azure, in chief a mullet of six points between two crosses patée of the last, and in base the front elevation of a chapel argent"], borne by Brown-Westhead.

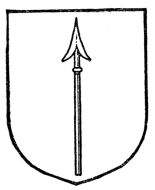

Arrows are very frequently found, and the arms of Hales supply one of the many examples of this charge, while a bow—without the arrows—may be instanced in the shield of Bowes: "Ermine, three bows bent and stringed palewise in fess proper."

Arrow-Heads and Pheons are of common usage, and occur in the arms of Foster and many other families. Pheons, it may be noticed in passing, are arrow-heads with an inner engrailed edge (Fig. 502), while when depicted without this peculiarity they are termed "broad arrows" (Fig. 503). This is not a distinction very stringently adhered to.

Charges associated with warfare and military defences are frequently to be found both in English and foreign heraldry.

Battle-Axes (Fig. 504), for example, may be seen in the shield of Firth and in that of Renty in Artois, which has: "Argent, three doloires, or broad-axes, gules, those in chief addorsed." In blazoning a battle-axe care should be taken to specify the fact if the head is of a different colour, as is frequently the case.

The somewhat infrequent device of a Battering-Ram is seen in the arms of Bertie, who bore: "Argent, three battering-rams fesswise in pale proper, armed and garnished azure."

An instrument of military defence consisting of an iron frame of four points, and called a Caltrap (Fig. 505) or Galtrap (and sometimes a Cheval trap, from its use of impeding the approach of cavalry), is found in the arms of Trappe ["Argent, three caltraps sable"], Gilstrap and other families; while French armory supplies us with another example in the case of the family of Guetteville de Guénonville, who bore for arms: "D'argent, semée de chausse-trapes de sable." Caltraps are also strewn upon the compartment upon which the supporters to the arms of the Earl of Perth are placed.

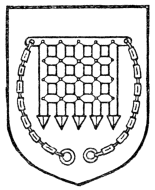

As the well-known badge of the Royal House of Tudor, the Portcullis (Fig. 506) is familiar to any one conversant with Henry VII.'s Chapel at Westminster Abbey, but it also appears as a charge in the arms of the family of Wingate ["Gules, a portcullis and a chief embattled or"], where it forms an obvious pun on the earliest form of the name, viz. Windygate, whilst it figures also as the crest of the Dukes of Beaufort ["A portcullis or, nailed azure, chained of the first"]. The disposition of the chains is a matter always left to the discretion of the artist.

Examples of Beacons (Fig. 507) are furnished by the achievements of the family of Compton and of the town of Wolverhampton. A fire chest occurs in the arms of Critchett (vide p. 261).

Chains are singularly scarce in armory, and indeed nearly wholly absent as charges, usually occurring where they do as part of the crest. The English shield of Anderton, it is true, bears: "Sable, three chains argent;" while another one (Duppa de Uphaugh) has: "Quarterly, 1 and 4, a lion's paw couped in fess between two chains or, a chief nebuly of the last, thereon two roses of the first, barbed and seeded proper (for Duppa); 2 and 3, party fess azure and sable, a trident fesswise or, between three turbots argent (for Turbutt)." In Continental heraldry, however, chains are more frequently met with. Principal amongst these cases maybe cited the arms of Navarre ("Gules, a cross saltire and double orle of chains, linked together or"), while many other instances are found in the armories of Southern France and of Spain.

Bombs or Grenades (Fig. 508), for Heraldry does not distinguish, figure in the shields of Vavasseur, Jervoise, Boycott, and many other families.

Among the more recent grants Cannon have figured, as in the case of the Pilter arms and in those of the burgh of Portobello; while an earlier counterpart, in the form of a culverin, forms the charge of the Leigh family: "Argent, a culverin in fess sable."

The Column appears as a crest in the achievement of Coles. Between two cross crosslets it occurs in the arms of Adam of Maryburgh ["Vert, a Corinthian column with capital and base in pale proper, between two cross crosslets fitchée in fess or"], while the arms of the See of Sodor and Man are blazoned: "Argent, upon a pedestal the Virgin Mary with her arms extended between two pillars, in the dexter hand a church proper, in base the arms of Man in an escutcheon." Major, of Suffolk, bears: "Azure, three Corinthian columns, each surmounted by a ball, two and one argent." It is necessary to specify the kind of column in the blazon.