Fig. 512.—Arms of William Shakespeare the poet (d. 1616): Or, on a bend sable, a tilting-spear of the field.

Scaling-Ladders (Fig. 509) (viz. ordinary-shaped ladders with grapnels affixed to the tops) are to be seen in the English coats of D'Urban and Lloyd, while the Veronese Princes della Scala bore the ordinary ladder: "Gules, a ladder of four steps in pale argent." A further instance of this form of the charge occurs in the Swiss shield of Laiterberg: "Argent, two ladders in saltire gules."

Spears and Spear-Heads are to be found in the arms of many families both in England, Wales, and abroad; for example, in the arms of Amherst and Edwards. Distinction must be drawn between the lance or javelin (Fig. 510) and the heraldic tilting-spear (Fig. 511), particularly as the latter is always depicted with the sharp point for warfare instead of the blunted point which was actually used in the tournament. The Shakespeare arms (Fig. 512) are: "Or, on a bend sable a tilting-spear of the field," while "Azure, a lance or enfiled at its point by an annulet argent" represents the French family of Danby.

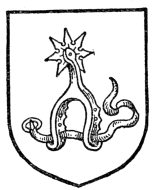

Spurs (Fig. 513) occur in coat armour as such in the arms of Knight and Harben, and also occasionally "winged" (Fig. 514), as in the crest of Johnston.

Spur-Rowels, or Spur-Revels, are to be met with under that name, but they are, and are more often termed, "mullets of five points pierced."

Examples of Stirrups are but infrequent, and the best-known one (as regards English armory) is that of Scudamore, while the Polish Counts Brzostowski bore: "Gules, a stirrup argent, within a bordure or."

Stones are even more rare, though a solitary example may be quoted in the arms of Staniland: Per pale or and vert, a pale counterchanged, three eagles displayed two and one, and as many flint-stones one and two all proper. The "vigilance" of the crane has been already alluded to on page 247. The mention of stones brings one to the kindred subject of Catapults. These engines of war, needless to say on a very much larger scale than the object which is nowadays associated with the term, were also known by the name balistæ, and also by that of swepe. Their occurrence is very infrequent, but for that very reason one may, perhaps, draw attention to the arms of the (English) family of Magnall: "Argent, a swepe azure, charged with a stone or."

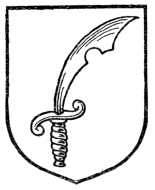

Swords, differing in number, position, and kind are, perhaps, of this class of charge the most numerous. A single sword as a charge may be seen in the shield of Dick of Wicklow, and Macfie, and a sword entwined by a serpent in that of Mackesy. A flaming sword occurs in the arms of Maddocks and Lewis. Swords frequently figure, too, in the hands or paws of supporters, accordingly as the latter are human figures or animals, whilst they figure as the "supporters" themselves in the unique case of the French family of Bastard, whose shield is cottised by "two swords, point in base." The heraldic sword is represented as Fig. 515, the blade of the dagger being shorter and more pointed. The scymitar follows the form depicted in Fig. 516.

A Seax is the term employed to denote a curved scimitar, or falchion, having a notch at the back of the blade (Fig. 517). In heraldry the use of this last is fairly frequent, though generally, it must be added, in shields of arms of doubtful authority. As such they are to be seen, amongst others, in the reputed arms of Middlesex, and owing to this origin they were included in the grant of arms to the town of Ealing. The sabre and the cutlass when so blazoned follow their utilitarian patterns.

Torches or Firebrands are depicted in the arms and crest of Gillman and Tyson.

Barnacles (or Breys)—horse curbs—occur in some of the earlier coats, as in the arms of Wyatt ["Gules, a barnacle argent"], while another family of the same name (or, possibly, Wyot) bore: "Per fess gules and azure (one or) three barnacles argent".

Bells are well instanced in the shield of Porter, and the poet Wordsworth bore: "Argent, three bells azure." It may be noted in passing that in Continental armory the clapper is frequently of a different tincture to that of the bell, as, for instance, "D'Azure, à la cloche d'argent, butaillé [viz. with the clapper] de sable"—the arms of the Comtes de Bellegarse. A bell is assumed to be a church-bell (Fig. 518) unless blazoned as a hawk's bell (Fig. 519).

Bridle-Bits are of very infrequent use, though they may be seen in the achievement of the family of Milner.

The Torse (or wreath surmounting the helm) occasionally figures as a charge, for example, in the arms of Jocelyn and Joslin.

The Buckle is a charge which is of much more general use than some of the foregoing. It appears very frequently both in English and foreign heraldry—sometimes oval-shaped (Fig. 520), circular (Fig. 521), or square (Fig. 522), but more generally lozenge-shaped (Fig. 523), especially in the case of Continental arms. A somewhat curious variation occurs in the arms of the Prussian Counts Wallenrodt, which are: "Gules, a lozenge-shaped buckle argent, the tongue broken in the middle." It is, of course, purely an artistic detail in all these buckles whether the tongue is attached to a crossbar, as in Figs. 520 and 521, or not, as in Figs. 522 and 523. As a badge the buckle is used by the Pelhams, Earls of Chichester and Earls of Yarborough, and a lozenge-shaped arming buckle is the badge of Jerningham.

Cups (covered) appear in the Butler arms, and derived therefrom in the arms of the town of Warrington. Laurie, of Maxwelltown, bear: "Sable, a cup argent, issuing therefrom a garland between two laurel-branches all proper," and similar arms are registered in Ireland for Lowry. The Veronese family of Bicchieri bear: "Argent, a fess gules between three drinking-glasses half-filled with red wine proper." An uncovered cup occurs in the arms of Fox, derived by them from the crest of Croker, and another instance occurs in the arms of a family of Smith. In this connection we may note in passing the rare use of the device of a Vase, which forms a charge in the coat of the town of Burslem, whilst it is also to be met with in the crest of the family of Doulton: "On a wreath of the colours, a demi-lion sable, holding in the dexter paw a cross crosslet or, and resting the sinister upon an escutcheon charged with a vase proper." The motto is perhaps well worth recording; "Le beau est la splendeur de vrai."

The arms of both the city of Dundee and the University of Aberdeen afford instances of a Pot of Lilies, and Bowls occur in the arms of Bolding.

PLATE V.

Though blazoned as a Cauldron, the device occurring in the crest of De la Rue may be perhaps as fittingly described as an open bowl, and as such may find a place in this classification: "Between two olive-branches vert a cauldron gules, fired and issuant therefrom a snake nowed proper." The use of a Pitcher occurs in the arms of Bertrand de Monbocher, who bore at the siege of Carlaverock: "Argent, three pitchers sable (sometimes found gules) within a bordure sable bezanté;" and the arms of Standish are: "Sable, three standing dishes argent."

The somewhat singular charge of a Chart appears in the arms of Christopher, and also as the crest of a Scottish family of Cook.

Chess-Rooks (Fig. 524) are somewhat favourite heraldic devices, and are to be met with in a shield of Smith and the arms of Rocke of Clungunford.

The Crescent (Fig. 525) figures largely in all armories, both as a charge and (in English heraldry) as a difference.

Variations, too, of the form of the crescent occur, such as when the horns are turned to the dexter (Fig. 526), when it is termed "a crescent increscent," or simply "an increscent," or when they are turned to the sinister—when it is styled "decrescent" (Fig. 527). An instance of the crescent "reversed" may be seen in the shield of the Austrian family of Puckberg, whose blazon was: "Azure, three crescents, those in chief addorsed, that in base reversed." In English "difference marks" the crescent is used to denote the second son, but under this character it will be discussed later.

Independently of its use in conjunction with ecclesiastical armory, the Crosier (Fig. 528) is not widely used in ordinary achievements. It does occur, however, as a principal charge, as in the arms of the Irish family of Crozier and in the arms of Benoit (in Dauphiny) ["Gules, a pastoral staff argent"], while it forms part of the crest of Alford. The term "crosier" is synonymous with the pastoral or episcopal staff, and is independent of the cross which is borne before (and not by) Archbishops and Metropolitans. The use of pastoral staves as charges is also to be seen in the shield of Were, while MacLaurin of Dreghorn bears: "Argent, a shepherd's crook sable." The Palmer's Staff (Fig. 529) has been introduced into many coats of arms for families having the surname of Palmer, as has also the palmer's wallet.

Cushions, somewhat strangely, form the charges in a number of British shields, occurring, for example, in the arms of Brisbane, and on the shield of the Johnstone family. In Scottish heraldry, indeed, cushions appear to have been of very ancient (and general) use, and are frequently to be met with. The Earls of Moray bore: "Argent, three cushions lozengewise within a double tressure flory-counterflory gules," but an English example occurs in the arms of Hutton.

The Distaff, which is supposed to be the origin of the lozenge upon which a lady bears her arms, is seldom seen in heraldry, but the family of Body, for instance, bear one in chief, and three occur in the arms of a family of Lees.

The Shuttle (Fig. 530) occurs in the arms of Shuttleworth, and in those of the town of Leigh, while the shield of the borough of Pudsey affords an illustration of shuttles in conjunction with a woolpack (Fig. 531).

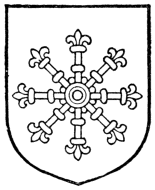

The Escarbuncle (Fig. 532) is an instance of a charge having so developed by the evolution of an integral part of the shield itself. In ancient warfare shields were sometimes strengthened by being bound with iron bands radiating from the centre, and these bands, from the shape they assumed, became in course of time a charge in themselves under the term escarbuncle.

The crest of the Fanmakers' Company is: "A hand couped proper holding a fan displayed," while the chief charge in the arms is "... a fan displayed ... the sticks gules." This, however, is the only case I can cite of this object.

The Fasces (Fig. 533), emblematic of the Roman magisterial office, is very frequently introduced in grants of arms to Mayors and Lord Mayors, which no doubt accounts for its appearance in the arms of Durning-Lawrence, Knill, Evans, and Spokes.

An instance of Fetterlocks (Fig. 534) occurs in the arms of Kirkwood, and also in the coat of Lockhart and the crest of Wyndham. A chain is often substituted for the bow of the lock. The modern padlock has been introduced into the grant of arms to the town of Wolverhampton.

Keys, the emblem of St. Peter, and, as such, part of the insignia of His Holiness the Pope, occur in many ecclesiastical coats, the arms of the Fishmongers' Livery Company, and many families.

Flames of Fire are not frequently met with, but they are to be found in the arms of Baikie, and as crests they figure in the achievements of Graham-Wigan, and also in conjunction with keys in that of Flavel. In connection with certain other objects flames are common enough. The phœnix always issues from flames, and a salamander is always in the midst of flames (Fig. 437). The flaming sword, a device, by the way, included in the recent grant to Sir George Lewis, Bart., has been already alluded to, as has also the flaming brand. A notable example of the torch occurs in the crest of Sir William Gull, Bart., no doubt an allusion (as is his augmentation) to the skill by which he kept the torch of life burning in the then Prince of Wales during his serious illness in 1871. A flaming mountain occurs as the crest of several families of the name of Grant.

A curious instrument now known nearly exclusively in connection with its use by farriers, and termed a Fleam (Fig. 535), occurs on the chief of the shield of Moore. A fleam, however, is the ancient form and name of a surgeon's lancet, and some connection with surgery may be presumed when it occurs. It is one of the charges in the arms recently granted to Sir Frederick Treves, Bart.

Furison.—This singular charge occurs in the shield of Black, and also in that of Steel. Furisons were apparently the instruments by which fire was struck from flint stones.

Charges in connection with music and musical instruments do not occur very frequently, though the heraldic use of the Clarion (Fig. 536) and the Harp may perhaps be mentioned. The bugle-horn (Fig. 537) also occurs "stringed" (Fig. 538), and when the bands round it are of a different colour it is termed "veruled" or "virolled" of that colour.

The Human Heart, which should perhaps have been more correctly referred to in an earlier chapter, is a charge which is well known in heraldry, both English and foreign. Perhaps the best known examples of the heart ensigned with a crown is seen in the shields of Douglas and Johnstone. The legend which accounts for the appearance of this charge in the arms of Douglas is too well known to need repetition.

Ingots of silver occur in the shield of the borough of St. Helens, whilst the family of Woollan go one better by bearing ingots of gold.

A Maunch (Fig. 539), which is a well-known heraldic term for the sleeve, is, as it is drawn, scarcely recognisable as such. Nevertheless its evolution can be clearly traced. The maunch—which, of course, as a heraldic charge, originated in the knightly "favour" of a lady's sleeve—was borne from the earliest periods in different tinctures by the three historic families of Conyers, Hastings, and Wharton. Other garments have been used as heraldic charges; gloves in the arms of Fletcher and Barttelot; stockings in the arms of Hose; a boot in the crest of Hussy, and a hat in the arms of Huth. Armour is frequently met with, a cuirass appearing in the crest of Somers, helmets in the arms of Salvesen, Trayner, Roberton, and many other families, gauntlets (Fig. 540), which need to be specified as dexter or sinister, in the arms of Vane and the crest of Burton, and a morion (Fig. 541) in the crest of Pixley. The Garter is, of course, due to that Order of knighthood; and the Blue Mantle of the same Order, besides giving his title to one of the Pursuivants of Arms, who uses it as his badge, has also been used as a charge.

The Mill-rind or Fer-de-moline is, of course, as its name implies, the iron from the centre of a grindstone. It is depicted in varying forms, more or less recognisable as the real thing (Fig. 542).

Mirrors occur almost exclusively in crests and in connection with mermaids, who, as a general rule, are represented as holding one in the dexter hand with a comb in the sinister. Very occasionally, however, mirrors appear as charges, an example being that of the Counts Spiegel zum Desenberg, who bore: "Gules, three round mirrors argent in square frames or."

Symbols connected with the Sacred Passion—other than the cross itself—are not of very general use in armory, though there are instances of the Passion-Nails being used, as, for example, in the shield of Procter viz.: "Or, three passion-nails sable."

Pelts, or Hides, occur in the shield of Pilter, and the Fleece has been mentioned under the division of Rams and Sheep.

Plummets (or Sinkers used by masons) form the charges in the arms of Jennings.

An instance of a Pyramid is met with in the crest of Malcolm, Bart., and an Obelisk in that of the town of Todmorden.

The shield of Crookes affords an example of two devices of very rare occurrence, viz. a Prism and a Radiometer.

Water, lakes, ships, &c., are constantly met with in armory, but a few instances must suffice. The various methods of heraldically depicting water have been already referred to (pages 88 and 151).

Three Wells figure in the arms of Hodsoll, and a masoned well in that of Camberwell. The shields of Stourton and Mansergh supply instances of heraldic Fountains, whilst the arms of Brunner and of Franco contain Fountains of the ordinary kind. A Tarn, or Loch, occurs in the shield of the family of Tarn, while Lord Loch bears: "Or, a saltire engrailed sable, between in fess two swans in water proper, all within a bordure vert."

The use of Ships may be instanced by the arms of many families, while a Galley or Lymphad (Fig. 543) occurs in the arms of Campbell, Macdonald, Galbraith, Macfie, and numerous other families, and also in the arms of the town of Oban. Another instance of a coat of arms in which a galley appears will be found in the arms recently granted to the burgh of Alloa, while the towns of Wandsworth and Lerwick each afford instances of a Dragon Ship. The Prow of a Galley appears in the arms of Pitcher.

A modern form of ship in the shape of a Yacht may be seen in the arms of Ryde; while two Scottish families afford instances of the use of the Ark. "Argent, an ark on the waters proper, surmounted of a dove azure, bearing in her beak an olive-branch vert," are the arms borne by Gellie of Blackford; and "Argent, an ark in the sea proper, in chief a dove azure, in her beak a branch of olive of the second, within a bordure of the third" are quoted as the arms of Primrose Gailliez of Chorleywood. Lastly, we may note the appropriate use of a Steamer in the arms of Barrow-in-Furness. The curious figure of the lion dimidiated with the hulk of a ship which is met with in the arms of several of the towns of the Cinque Ports has been referred to on page 182.

Clouds form part of the arms of Leeson, which are: "Gules, a chief nebuly argent, the rays of the sun issuing therefrom or."

The Rainbow (Fig. 544), though not in itself a distinctly modern charge, for it occurs in the crest of Hope, has been of late very frequently granted as part of a crest. Instances occur in the crest of the family of Pontifex, and again in that of Thurston, and of Wigan. Its use as a part of a crest is to be deprecated, but in these days of complicated armory it might very advantageously be introduced as a charge upon a shield.

An unusual device, the Thunderbolt, is the crest of Carnegy. The arms of the German family of Donnersperg very appropriately are: "Sable, three thunderbolts or issuing from a chief nebuly argent, in base a mount of three coupeaux of the second." The arms of the town of Blackpool furnish an instance of a thunderbolt in dangerous conjunction with windmill sails.

Stars, a very common charge, may be instanced as borne under that name by the Scottish shield of Alston. There has, owing to their similarity, been much confusion between stars, estoiles, and mullets. The difficulty is increased by the fact that no very definite lines have ever been followed officially. In England stars under that name are practically unknown. When the rays are wavy the charge is termed an estoile, but when they are straight the term mullet is used. That being so, these rules follow: that the estoile is never pierced (and from the accepted method of depicting the estoile this would hardly seem very feasible), and that unless the number of points is specified there will be six (see Fig. 545). Other numbers are quite permissible, but the number of points (more usually in an estoile termed "rays") must be stated. The arm of Hobart, for example, are: "Sable, an estoile of eight rays or, between two flaunches ermine." An estoile of sixteen rays is used by the town of Ilchester, but the arms are not of any authority. Everything with straight points being in England a mullet, it naturally follows that the English practice permits a mullet to be plain (Fig. 546) or pierced (Fig. 547). Mullets are occasionally met with pierced of a colour other than the field they are charged upon. According to the English practice, therefore, the mullet is not represented as pierced unless it is expressly stated to be so. The mullet both in England and Scotland is of five points unless a greater number are specified. But mullets pierced and unpierced of six (Fig. 548) or eight points (Fig. 549) are frequent enough in English armory.

The Scottish practice differs, and it must be admitted that it is more correct than the English, though, strange to say, more complicated. In Scottish armory they have the estoile, the star, and the mullet or the spur-revel. As to the estoile, of course, their practice is similar to the English. But in Scotland a straight-pointed charge is a mullet if it be pierced, and a star if it be not. As a mullet is really the "molette" or rowel of a spur, it certainly could not exist as a fact unpierced. Nevertheless it is by no means stringently adhered to in that country, and they make confusion worse confounded by the frequent use of the additional name of "spur-rowel," or "spur-revel" for the pierced mullet. The mullet occurs in the arms of Vere, and was also the badge of that family. The part this badge once played in history is well known. Had the De Veres worn another badge on that fatal day the course of English history might have been changed.

The six-pointed mullet pierced occurs in the arms of De Clinton.

The Sun in Splendour—(Fig. 550) always so blazoned—is never represented without the surrounding rays, but the human face is not essential though usual to its heraldic use. The rays are alternately straight and wavy, indicative of the light and heat we derive therefrom, a typical piece of genuine symbolism. It is a charge in the arms of Hurst, Pearson, and many other families; and a demi-sun issuing in base occurs in the arms of Davies (Plate VI.) and of Westworth. The coat of Warde-Aldam affords an example of the Rays of the sun alone.

A Scottish coat, that of Baillie of Walstoun, has "Azure, the moon in her complement, between nine mullets argent, three, two, three and one." The term "in her complement" signifies that the moon is full, but with the moon no rays are shown, in this of course differing from the sun in splendour. The face is usually represented in the full moon, and sometimes in the crescent moon, but the crescent moon must not be confused with the ordinary heraldic crescent.

In concluding this class of charges, we may fitly do so by an allusion to the shield of Sir William Herschel, with its appropriate though clumsy device of a Telescope.

As may be naturally expected, the insignia of sovereignty are of very frequent occurrence in all armories, both English and foreign. Long before the days of heraldry, some form of decoration for the head to indicate rank and power had been in vogue amongst, it is hardly too much to say, all nations on the earth. As in most things, Western nations have borrowed both ideas, and added developments of those ideas, from the East, and in traversing the range of armory, where crowns and coronets appear in modern Western heraldry, we find a large proportion of these devices are studiously and of purpose delineated as being Eastern.

With crowns and coronets as symbols of rank I am not now, of course, concerned, but only with those cases which may be cited as supplying examples where the different kinds of crowns appear either as charges on shields, or as forming parts of crests.

Crowns, in heraldry, may be differentiated under the Royal or the Imperial, the Eastern or antique, the Naval, and the Mural, which with the Crowns Celestial, Vallery and Palisado are all known as charges. Modern grants of crowns of Eastern character in connection with valuable service performed in the East by the recipient may be instanced; e.g. by the Eastern Crown in the grant to Sir Abraham Roberts, G.C.B., the father of Field-Marshal Earl Roberts, K.G.

In order of antiquity one may best perhaps at the outset allude to the arms borne by the seaport towns of Boston, and of Kingston-on-Hull (or Hull, as the town is usually called), inasmuch as a tradition has it that the three crowns which figure on the shield of each of these towns originate from a recognised device of merchantmen, who, travelling in and trading with the East and likening themselves to the Magi, in their Bethlehem visit, adopted these crowns as the device or badge of their business. The same remarks may apply to the arms of Cologne: "Argent, on a chief gules, three crowns or."

From this fact (if the tradition be one) to the adoption of the same device by the towns to which these merchants traded is not a far step.

One may notice in passing that, unlike what from the legend one would expect, these crowns are not of Eastern design, but of a class wholly connected with heraldry itself. The legend and device, however, are both much older than these modern minutiæ of detail.

The Archbishopric of York has the well-known coat: "Gules, two keys in saltire argent, in chief a regal crown proper."

The reputed arms of St. Etheldreda, who was both Queen, and also Abbess of Ely, find their perpetuation in the arms of that See, which are: "Gules, three ducal (an early form of the Royal) crowns or;" while the recently-created See of St. Alban's affords an example of a celestial crown: "Azure, a saltire or, a sword in pale proper; in chief a celestial crown of the second." The Celestial Crown is to be observed in the arms of the borough of Kensington and as a part of the crest of Dunbar. The See of Bristol bears: "Sable, three open crowns in pale or." The Royal or Imperial Crown occurs in the crest of Eye, while an Imperial Crown occurs in the crests of Robertson, Wolfe, and Lane.

The family of Douglas affords an instance of a crown ensigning a human heart. The arms of Toledo afford another case in point, being: "Azure, a Royal crown or" (the cap being gules).

Antique Crowns—as such—appear in the arms of Fraser and also in the arms of Grant.

The crest of the Marquess of Ripon supplies an unusual variation, inasmuch as it issues from a coronet composed of fleurs-de-lis.

The other chief emblem of sovereignty—the Sceptre—is occasionally met with, as in the Whitgreave crest of augmentation.

The Marquises of Mun bear the Imperial orb: "Azure, an orb argent, banded, and surmounted by the cross or." The reason for the selection of this particular charge in the grant of arms [Azure, on a fess or, a horse courant gules, between three orbs gold, banded of the third] to Sir H. E. Moss, of the Empire Theatre in Edinburgh and the London Hippodrome, will be readily guessed.

Under the classification of tools and implements the Pick may be noted, this being depicted in the arms of Mawdsley, Moseley, and Pigott, and a pick and shovel in the arms of Hales.

The arms of Crawshay supply an instance of a Plough—a charge which also occurs in the arms of Waterlow and the crest of Provand, but is otherwise of very infrequent occurrence.

In English armory the use of Scythes, or, as they are sometimes termed, Sneds, is but occasional, though, as was only to be expected, this device appears in the Sneyd coat, as follows: "Argent, a scythe, the blade in chief, the sned in bend sinister sable, in the fess point a fleur-de-lis of the second." In Poland the Counts Jezierski bore: "Gules, two scythe-blades in oval, the points crossing each other argent, and the ends in base tied together or, the whole surmounted in chief by a cross-patriarchal-patée, of which the lower arm on the sinister side is wanting."

Two sickles appear in the arms of Shearer, while the Hungerford crest in the case of the Holdich-Hungerford family is blazoned: "Out of a ducal coronet or, a pepper garb of the first between two sickles erect proper." The sickle was the badge of the Hungerfords.

A Balance forms one of the charges of the Scottish Corporation of the Dean and Faculty of Advocates: "Gules, a balance or, and a sword argent in saltire, surmounted of an escutcheon of the second, charged with a lion rampant within a double tressure flory counterflory of the first," but it is a charge of infrequent appearance. It also figures in the arms of the Institute of Chartered Accountants.