Bannerman of Elsick bears a Banner for arms: "Gules, a banner displayed argent and thereon on a canton azure a saltire argent as the badge of Scotland."

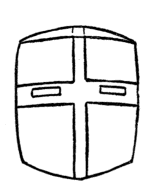

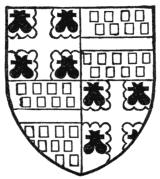

Fig. 552.—Arms of Henry Bourchier, Earl of Essex, K.G.: Quarterly, 1 and 4, argent, a cross engrailed gules, between four water-bougets sable (for Bourchier); 2 and 3, gules, billetté or, a fess argent (for Louvain). (From his seal.)

Books are frequently made use of. The arms of Rylands, the family to whose generosity Manchester owes the Rylands Library, afford a case in point, and such charges occur in the arms of the Universities of both Oxford and Cambridge, and in many other university and collegiate achievements.

Buckets and Water-bougets (Fig. 551) can claim a wide use. In English armory Pemberton has three buckets, and water-bougets appear in the well-known arms of Bourchier (Fig. 552). Water-bougets, which are really the old form of water-bucket, were leather bags or bottles, two of which were carried on a stick over the shoulder. The heraldic water-bouget represents the pair.

For an instance of the heraldic usage of the Comb the case of the arms of Ponsonby, Earls of Bessborough, may be cited. Combs also figure in the delightfully punning Scottish coat for Rocheid.

Generally, however, when they do occur in heraldry they represent combs for carding wool, as in the shield of Tunstall: "Sable, three wool-combs argent," while the Russian Counts Anrep-Elmpt use: "Or, a comb in bend azure, the teeth downwards."

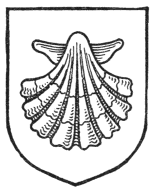

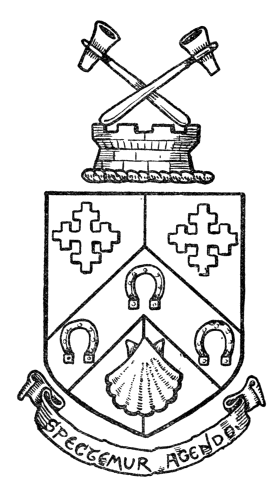

Escallops (Fig. 553) rank as one of the most widely used heraldic charges in all countries. They figured in early days outside the limits of heraldry as the badge of pilgrims going to the Holy Land, and may be seen on the shields of many families at the period of the Crusades. Many other families have adopted them, in the hope of a similar interpretation being applied to the appearance of them in their own arms. Indeed, so numerous are the cases in which they occur that a few representative ones must suffice.

They will be found in the arms of the Lords Dacre, who bore: "Gules, three escallops argent;" and an escallop argent was used by the same family as a badge. The Scottish family of Pringle, of Greenknowe, supplies an instance in: "Azure, three escallops or within a bordure engrailed of the last;" while the Irish Earls of Bandon bore: "Argent, on a bend azure three escallops of the field."

Hammers figure in the crests of Hammersmith (Fig. 554) and of Swindon (Plate VI.), and a hammer is held in the claw of the demi-dragon which is the crest of Fox-Davies of Coalbrookdale, co. Salop (Plate VI.).

A Lantern is a charge on the shield of Cowper, and the arms of the town of Hove afford an absolutely unique instance of the use of Leg-Irons.

Three towns—Eccles, Bootle, and Ramsgate—supply cases in their arms in which a Lighthouse is depicted, and this charge would appear, so far as can be ascertained, not only to be restricted to English armory, but to the three towns now named.

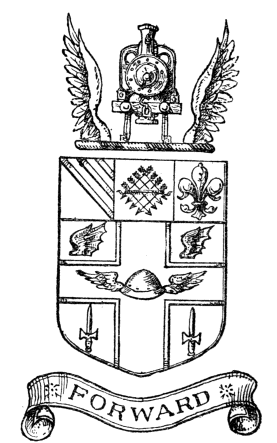

Locomotives appear in the arms of Swindon (Plate VI.) and the Great Central Railway (Fig. 555).

Of a similar industrial character is the curious coat of arms granted at his express wish to the late Mr. Samson Fox of Leeds and Harrogate, which contains a representation of the Corrugated Boiler-Flue which formed the basis of his fortune.

An instance of the use of a Sand-Glass occurs in the arms of the Scottish family of Joass of Collinwort, which are thus blazoned: "Vert, a sand-glass running argent, and in chief the Holy Bible expanded proper."

A Scottish corporation, too, supplies a somewhat unusual charge, that of Scissors: "Azure, a pair of scissors or" (Incorporation of Tailors of Aberdeen); though a Swabian family (by name Jungingen) has for its arms: "Azure, a pair of scissors open, blades upwards argent."

Barrels and Casks, which in heraldry are always known as tuns, naturally figure in many shields where the name lends itself to a pun, as in the arms of Bolton.

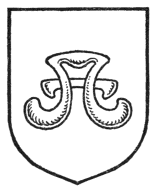

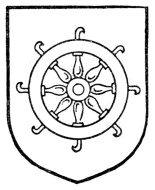

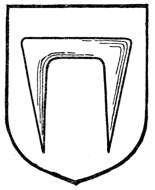

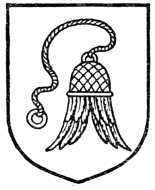

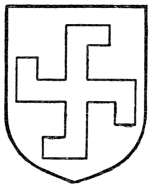

Wheels occur in the shields of Turner ["Argent, gutté-de-sang, a wheel of eight spokes sable, on a chief wavy azure, a dolphin naiant of the first"] and Carter, and also in the arms of Gooch. The Catherine Wheel (Fig. 556), however, is the most usual heraldic form. The Staple (Fig. 557) and the Hawk's Lure (Fig. 558) deserve mention, and I will wind up the list of examples with the Fylfot (Fig. 559), which no one knows the meaning or origin of.

The list of heraldic charges is very far, indeed, from being exhausted. The foregoing must, however, suffice; but those who are curious to pursue this branch of the subject further should examine the arms, both ancient and modern, of towns and trade corporations.

CHAPTER XX

THE HERALDIC HELMET

Since one's earliest lessons in the rules of heraldry, we have been taught, as one of the fundamental laws of the achievement, that the helmet by its shape and position is indicative of rank; and we early learnt by rote that the esquire's helmet was of steel, and was placed in profile, with the visor closed: the helmet of the knight and baronet was to be open and affronté; that the helmet of the peer must be of silver, guarded by grilles and placed in profile; and that the royal helmet was of gold, with grilles, and affronté. Until recent years certain stereotyped forms of the helmet for these varying circumstances were in use, hideous alike both in the regularity of their usage and the atrocious shapes into which they had been evolved. These regulations, like some other adjuncts of heraldic art, are comparatively speaking of modern origin. Heraldry in its earlier and better days knew them not, and they came into vogue about the Stuart times, when heraldic art was distinctly on the wane. It is puzzling to conceive a desire to stereotype these particular forms, and we take it that the fact, which is undoubted, arose from the lack of heraldic knowledge on the part of the artists, who, having one form before them, which they were assured was correct, under the circumstances simply reproduced this particular form in facsimile time after time, not knowing how far they might deviate and still remain correct. The knowledge of heraldry by the heraldic artist was the real point underlying the excellence of mediæval heraldic art, and underlying the excellence of much of the heraldic art in the revival of the last few years. As it has been often pointed out, in olden times they "played" with heraldry, and therein lay the excellence of that period. The old men knew the lines within which they could "play," and knew the laws which they could not transgress. Their successors, ignorant of the laws of arms, and afraid of the hidden meanings of armory, had none but the stereotyped lines to follow. The result was bad. Let us first consider the development of the actual helmet, and then its application to heraldic purposes will be more readily followed.

To the modern mind, which grumbles at the weight of present-day head coverings, it is often a matter of great wonder how the knights of ancient days managed to put up with the heavy weight of the great iron helmet, with its wooden or leather crest. A careful study of ancient descriptions of tournaments and warfare will supply the clue to the explanation, which is simply that the helmet was very seldom worn. For ceremonial purposes and occasions it was carried by a page, and in actual use it was carried slung at the saddle-bow, until the last moment, when it was donned for action as blows and close contact became imminent. Then, by the nature of its construction, the weight was carried by the shoulders, the head and neck moving freely within necessary limits inside. All this will be more readily apparent, when the helmet itself is considered. Our present-day ideas of helmets—their shape, their size, and their proportions—are largely taken from the specimens manufactured (not necessarily in modern times) for ceremonial purposes; e.g. for exhibition as insignia of knighthood. By far the larger proportion of the genuine helmets now to be seen were purposely made (certainly at remote dates) not for actual use in battle or tournament, but for ceremonial use, chiefly at funerals. Few, indeed, are the examples still existing of helmets which have been actually used in battle or tournament. Why there are so few remaining to us, when every person of position must necessarily have possessed one throughout the Plantagenet period, and probably at any rate to the end of the reign of Henry VII., is a mystery which has puzzled many people—for helmets are not, like glass and china, subject to the vicissitudes of breakage. The reason is doubtless to be found in the fact that at that period they were so general, and so little out of the common, that they possessed no greater value than any other article of clothing; and whilst the real helmet, lacking a ceremonial value, was not preserved, the sham ceremonial helmet of a later period, possessing none but a ceremonial value, was preserved from ceremonial to ceremonial, and has been passed on to the present day. But a glance at so many of these helmets which exist will plainly show that it was quite impossible for any man's head to have gone inside them, and the sculptured helmets of what may seem to us uncouth shape and exaggerated size, which are occasionally to be found as part of a monumental effigy, are the size and shape of the helmets that were worn in battle. This accounts for the much larger-sized helmets in proportion to the size of shield which will be found in heraldic emblazonments of the Plantagenet and Tudor periods. The artists of those periods were accustomed to the sight of real helmets, and knew and drew the real proportion which existed between the fighting helmet and the fighting shield. Artists of Stuart and Georgian days knew only the ceremonial helmet, and consequently adopted and stereotyped its impossible shape, and equally impossible size. Victorian heraldic artists, ignorant alike of the actual and the ceremonial, reduced the size even further, and until the recent revulsion in heraldic art, with its reversion to older types, and its copying of older examples, the helmets of heraldry had reached the uttermost limits of absurdity.

The recent revival of heraldry is due to men with accurate and extensive knowledge, and many recent examples of heraldic art well compare with ancient types. One happy result of this revival is a return to older and better types of the helmet. But it is little use discarding the "heraldic" helmet of the stationer's shop unless a better and more accurate result can be shown, so that it will be well to trace in detail the progress of the real helmet from earliest times.

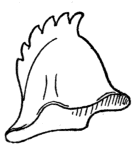

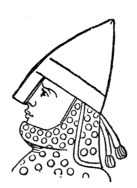

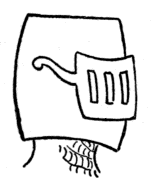

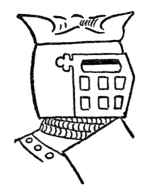

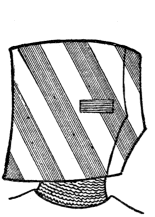

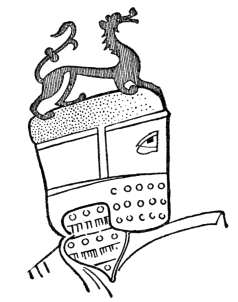

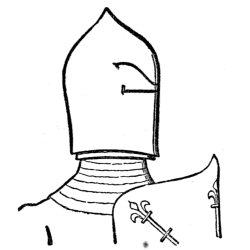

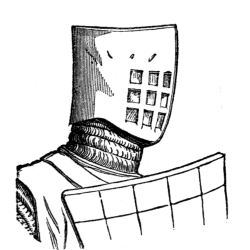

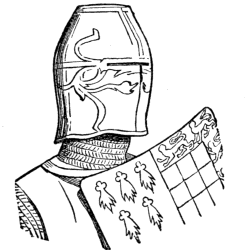

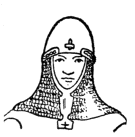

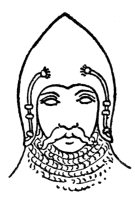

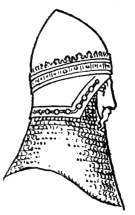

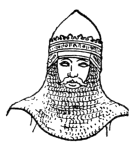

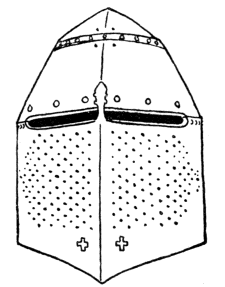

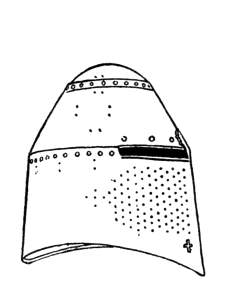

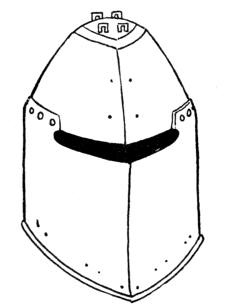

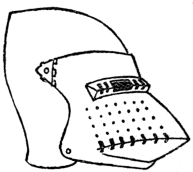

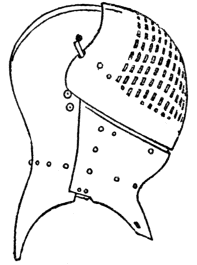

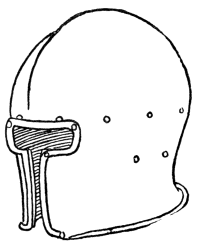

In the Anglo-Saxon period the common helmet was merely a cap of leather, often four-cornered, and with a serrated comb (Figs. 560 and 561), but men of rank had a conical one of metal (Fig. 562), which was frequently richly gilt. About the time of Edward the Confessor a small piece, of varying breadth, called a "nasal," was added (Fig. 563), which, with a quilted or gamboised hood, or one of mail, well protected the face, leaving little more than the eyes exposed; and in this form the helmet continued in general use until towards the end of the twelfth century, when we find it merged into or supplanted by the "chapelle-de-fer," which is first mentioned in documents at this period, and was shaped like a flat-topped, cylindrical cap. This, however, was soon enlarged so as to cover the whole head (Fig. 564), an opening being left for the features, which were sometimes protected by a movable "ventaille," or a visor, instead of the "nasal." This helmet (which was adopted by Richard I., who is also sometimes represented with a conical one) was the earliest form of the large war and tilting "heaume" (or helm), which was of great weight and strength, and often had only small openings or slits for the eyes (Figs. 565 and 566). These eyepieces were either one wide slit or two, one on either side. The former was, however, sometimes divided into two by an ornamental bar or buckle placed across. It was afterwards pointed at the top, and otherwise slightly varied in shape, but its general form appears to have been the same until the end of the fourteenth century (Figs. 567, 568). This type of helmet is usually known as the "pot-shaped." The helmets themselves were sometimes painted, and Fig. 569 represents an instance which is painted in green and white diagonal stripes. The illustration is from a parchment MS. of about 1241 now in the Town Library of Leipzic. Fig. 570 shows another German example of this type, being taken from the Eneit of Heinrich von Veldeke, a MS. now in the Royal Library in Berlin, belonging to the end of the twelfth century. The crest depicted in this case, a red lion, must be one of the earliest instances of a crest. These are the helmets which we find on early seals and effigies, as will be seen from Figs. 571-574.

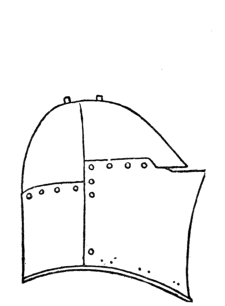

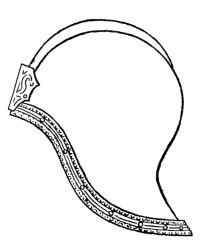

The cylindrical or "pot-shaped" helmet of the Plantagenets, however, disappears in the latter part of the thirteenth century, when we first find mention of the "bascinet" (from Old French for a basin), Figs. 575-579. This was at first merely a hemispherical steel cap, put over the coif of mail to protect the top of the head, when the knight wished to be relieved from the weight of his large helm (which he then slung at his back or carried on his saddlebow), but still did not consider the mail coif sufficient protection. It soon became pointed at the top, and gradually lower at the back, though not so much as to protect the neck. In the fourteenth century the mail, instead of being carried over the top of the head, was hung to the bottom rim of the helmet, and spread out over the shoulders, overlapping the cuirass. This was called the "camail," or "curtain of mail." It is shown in Figs. 576 and 577 fastened to the bascinet by a lace or thong passing through staples.

The large helm, which throughout the fourteenth century was still worn over the bascinet, did not fit down closely to the cuirass (though it may have been fastened to it with a leather strap), its bottom curve not being sufficiently arched for that purpose; nor did it wholly rest on the shoulders, but was probably wadded inside so as to fit closely to the bascinet.

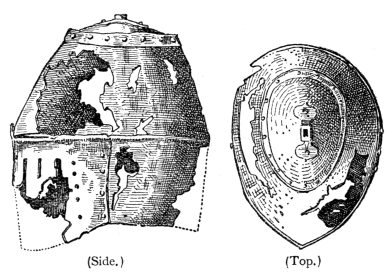

It is doubtful if any actual helm previous to the fourteenth century exists, and there are very few of that period remaining. In that of the Black Prince at Canterbury (Fig. 271) the lower, or cylindrical, portion is composed of a front and back piece, riveted together at the sides, and this was most likely the usual form of construction; but in the helm of Sir Richard Pembridge (Figs. 580 and 581) the three pieces (cylinder, conical piece, and top piece) of which it is formed are fixed with nails, and are so welded together that no trace of a join is visible. The edges of the metal, turned outwards round the ocularium, are very thick, and the bottom edge is rolled inwards over a thick wire, so as not to cut the surcoat. There are many twin holes in the helmet for the aiglets, by which the crest and lambrequin were attached, and in front, near the bottom, are two + shaped holes for the T bolt, which was fixed by a chain to the cuirass.

The helm of Sir Richard Hawberk (Figs. 582 and 583), who died in 1417, is made of five pieces, and is very thick and heavy. It is much more like the later form adapted for jousting, and was probably only for use in the tilt-yard; but, although more firmly fixed to the cuirass than the earlier helm, it did not fit closely down to it, as all later helms did.

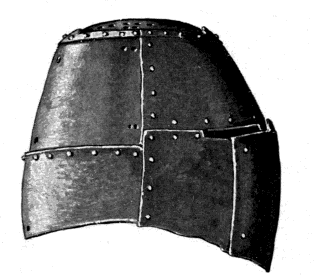

Singularly few examples of the pot-helmet actually exist. The "Linz" example (Figs. 584 and 585), which is now in the Francisco-Carolinum Museum at Linz, was dredged out of the Traun, and is unfortunately very much corroded by rust. The fastening-place for the crest, however, is well preserved. The example belongs to the first half of the fourteenth century.

The so-called "Pranker-Helm" (Fig. 586), from the chapter of Seckau, now in the collection of armour in the Historical Court Museum at Vienna, and belonging to the middle of the fourteenth century, could only have been used for tournaments. It is made of four strong hammered sheets of iron 1-2 millimetres thick, with other strengthening plates laid on. The helmet by itself weighs 5 kilogrammes 357 grammes.

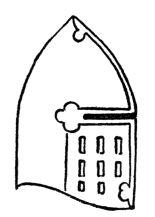

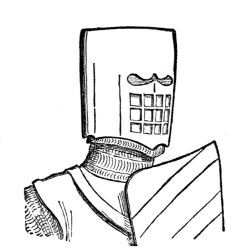

The custom of wearing the large helm over the bascinet being clumsy and troublesome, many kinds of visor were invented, so as to dispense with the large helm, except for jousting, two of which are represented in Figs. 575 and 579. In the first a plate shaped somewhat to the nose was attached to the part of the camail which covered the mouth. This plate, and the mail mouth-guard, when not in use, hung downwards towards the breast; but when in use it was drawn up and attached to a staple or locket on the front of the bascinet. This fashion, however, does not appear to have been adopted in England, but was peculiar to Germany, Austria, &c. None of these contrivances seem to have been very satisfactory, but towards the end of the fourteenth century the large and salient beaked visor was invented (Fig. 587). It was fixed to hinges at the sides of the bascinet with pins, and was removable at will. A high collar of steel was next added as a substitute for the camail. This form of helmet remained in use during the first half of the fifteenth century, and the large helm, which was only used for jousting, took a different form, or rather several different forms, which may be divided into three kinds. In this connection it should be remembered that the heavy jousting helmet to which the crest had relation was probably never used in actual warfare. The first was called a bascinet, and was used for combats on foot. It had an almost spherical crown-piece, and came right down to the cuirass, to which it was firmly fixed, and was, like all large helms of the fifteenth century, large enough for the wearer to move his head about freely inside. The helm of Sir Giles Capel (Fig. 588) is a good specimen of this class; it has a visor of great thickness, in which are a great number of holes, thus enabling the wearer to see in every direction. The "barbute," or ovoid bascinet, with a chin-piece riveted to it, was somewhat like this helm, and is often seen on the brasses of 1430-1450; the chin-piece retaining the name of "barbute," after the bascinet had gone out of fashion.

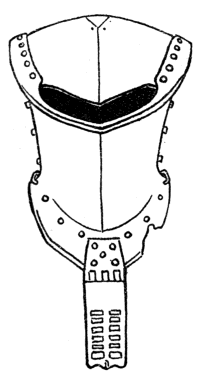

The second kind of large helm used in the fifteenth century was the "jousting-helm," which was of great strength, and firmly fixed to the cuirass. One from the Brocas Collection (Figs. 589 and 590, date about 1500) is perhaps the grandest helm in existence. It is formed of three pieces of different thicknesses (the front piece being the thickest), which are fixed together with strong iron rivets with salient heads and thin brass caps soldered to them. The arrangements for fixing it in front and behind are very complete and curious.

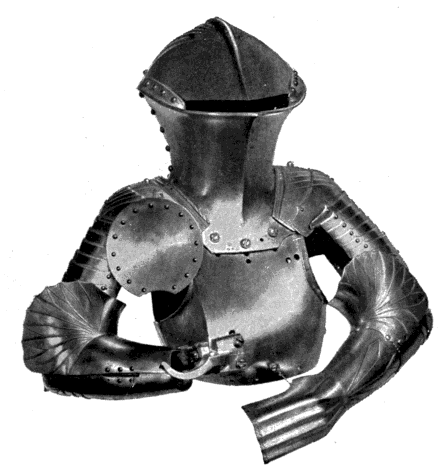

The manner in which the helmet was connected with the rest of the armour is shown in Fig. 591, which is a representation of a German suit of tilting armour of the period about 1480, now in the collection of armour at the Royal Museum in Vienna.

Of the same character, but of a somewhat different shape, is the helmet (Fig. 592) of Sir John Gostwick, who died in 1541, which is now in Willington Church, Bedfordshire. The illustration here given is taken from the Portfolio, No. 33. The visor opening on the right side of the helmet is evidently taken from an Italian model.

The third and last kind of helm was the "tournament helm," and was similar to the first kind, and also called a "bascinet"; but the visor was generally barred, or, instead of a movable visor, the bars were riveted on the helm, and sometimes the face was only protected by a sort of wire-work, like a fencing-mask. It was only used for the tourney or mêlée, when the weapons were the sword and mace.

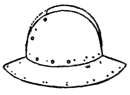

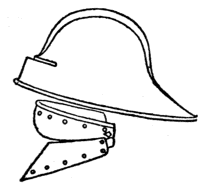

The "chapelle-de-fer," which was in use in the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth centuries, was a light iron head-piece, with a broad, flat brim, somewhat turned down. Fig. 593 represents one belonging to the end of the fifteenth century, which is one of the few remaining, and is delicately forged in one piece of thin, hard steel.

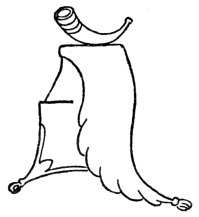

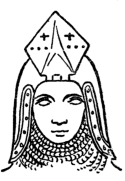

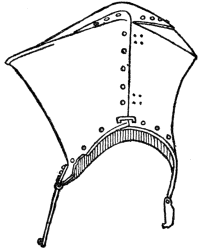

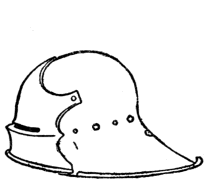

During the fourteenth century a new kind of helmet arose, called in England the "sallad," or "sallet." The word appears to have two derivations, each of which was applied to a different form of head-piece. First, the Italian "celata" (Fig. 594), which seems originally to have been a modification of the bascinet. Second, the German "schallern," the form of which was probably suggested by the chapelle-de-fer. Both of these were called by the French "salade," whence our English "sallad." The celata came lower down than the bascinet, protected the back and sides of the neck, and, closing round the cheeks, often left only the eyes, nose, and mouth exposed. A standard of mail protected the neck if required. In the fifteenth century the celata ceased to be pointed at the summit, and was curved outwards at the nape of the neck, as in Fig. 595.

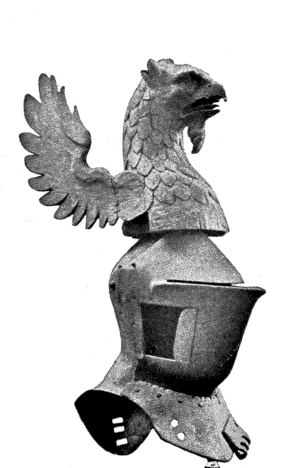

The "schallern" (from shale, a shell, or bowl), was really a helmet and visor in one piece; it had a slit for the eyes, a projecting brim, and a long tail, and was completed by a chin-piece, or "bavier" (Eng. "beaver"), which was strapped round the neck. Fig. 596 shows a German sallad and a Spanish beaver. The sallad was much used in the fifteenth century, during the latter half of which it often had a visor, as in one from Rhodes (Fig. 597), which has a spring catch on the right side to hold the visor in place when down. The rivets for its lining-cap have large, hollow, twisted heads, which are seldom found on existing sallads, though often seen in sculpture.

The schale, schallern (schêlern), or sallad, either with or without a visor, is very seldom seen in heraldic use. An instance, however, in which it has been made use of heraldically will be found in Fig. 598, which is from a pen and ink drawing in the Fest-Buch of Paulus Kel, a MS. now in the Royal Library at Munich. This shows the schallern with the slit for seeing through, and the fixed neck-guard. The "bart," "bavière," or beaver, for the protection of the under part of the face, is also visible. It is not joined to the helmet. The helmet bears the crest of Bavaria, the red-crowned golden lion of the Palatinate within the wings of the curiously disposed Bavarian tinctures. Fig. 599 (p. 316) is a very good representation of a schallern dating from the latter part of the fifteenth century, with a sliding neck-guard. It is reproduced from the Deutscher Herold, 1892, No. 2.