Ulster King of Arms has a staff of office which, however, really belongs to his office as Knight Attendant on the Most Illustrious Order of St. Patrick.

The Scottish Heralds each have a rod of ebony tipped with ivory, which has been sometimes stated to be a rod of office. This, however, is not the case, and the explanation of their possession of it is very simple. They are constantly called upon by virtue of their office to make from the Market Cross in Edinburgh the Royal Proclamations. Now these Proclamations are read from printed copies which in size of type and paper are always of the nature of a poster. The Herald would naturally find some difficulty in holding up a large piece of paper of this size on a windy day, in such a manner that it was easy to read from; consequently he winds it round his ebony staff, slowly unwinding it all the time as he reads.

Garter King of Arms, Lyon King of Arms, and Ulster King of Arms all possess badges of their offices which they wear about their necks.

The badge of Garter is of gold, having on both sides the arms of St. George, impaled with those of the Sovereign, within the Garter and motto, enamelled in their proper colours, and ensigned with the Royal crown.

The badge of Lyon King of Arms is oval, and is worn suspended by a broad green ribbon. The badge proper consists on the obverse of the effigy of St. Andrew bearing his cross before him, with a thistle beneath, all enamelled in the proper colours on an azure ground. The reverse contains the arms of Scotland, having in the lower parts of the badge a thistle, as on the other side; the whole surmounted with the Imperial crown.

The badge of "Ulster" is of gold, containing on one side the cross of St. Patrick, or, as it is described in the statutes, "The cross gules of the Order upon a field argent, impaled with the arms of the Realm of Ireland," and both encircled with the motto, "Quis Separabit," and the date of the institution of the Order, MDCCLXXXIII. The reverse exhibits the arms of the office of Ulster, viz.: "Or, a cross gules, on a chief of the last a lion of England between a harp and portcullis, all of the first," placed on a ground of green enamel, surrounded by a gold border with shamrocks, surmounted by an Imperial crown, and suspended by a sky-blue riband from the neck.

The arms of the Corporation of the College of Arms are: Argent, a cross gules between four doves, the dexter wing of each expanded and inverted azure. Crest: on a ducal coronet or, a dove rising azure. Supporters: two lions rampant guardant argent, ducally gorged or.

The official arms of the English Kings of Arms are:—

Garter King of Arms.—Argent, a cross gules, on a chief azure, a ducal coronet encircled with a garter, between a lion passant guardant on the dexter and a fleur-de-lis on the sinister all or.

Clarenceux King of Arms.—Argent, a cross gules, on a chief of the second a lion passant guardant or, crowned of the last.

Norroy King of Arms.—Argent, a cross gules, on a chief of the second a lion passant guardant crowned of the first, between a fleur-de-lis on the dexter and a key on the sinister of the last.

Badges have never been officially assigned to the various Heralds by any specific instruments of grant or record; but from a remote period certain of the Royal badges relating to their titles have been used by various Heralds, viz.:—

Lancaster.—The red rose of Lancaster ensigned by the Royal crown.

York.—The white rose of York en soleil ensigned by the Royal crown.

Richmond.—The red rose of Lancaster impaled with the white rose en soleil of York, the whole ensigned with the Royal crown.

Windsor.—Rays of the sun issuing from clouds.

The four Pursuivants make use of the badges from which they derive their titles.

The official arms of Lyon King of Arms and of Lyon Office are the same, namely: Argent, a lion sejant full-faced gules, holding in the dexter paw a thistle slipped vert and in the sinister a shield of the second; on a chief azure, a St. Andrew's cross of the field.

There are no official arms for Ulster's Office, that office, unlike the College of Arms, not being a corporate body, but the official arms of Ulster King of Arms are: Or, a cross gules, on a chief of the last a lion passant guardant between a harp and a portcullis all of the field.

CHAPTER IV

HERALDIC BRASSES

By Rev. WALTER J. KAYE, Junr., B.A., F.S.A., F.S.A. Scot.

Member of the Monumental Brass Society, London; Honorary Member of the Spalding Gentlemen's Society; Author of "A Brief History of Gosberton, in the County of Lincoln."

Monumental brasses do not merely afford a guide to the capricious changes of fashion in armour, in ecclesiastical vestments (which have altered but little), and in legal, civilian, and feminine costume, but they provide us also with a vast number of admirable specimens of heraldic art. The vandal and the fanatic have robbed us of many of these beautiful memorials, but of those which survive to our own day the earliest on the continent of Europe marks the last resting-place of Abbot Ysowilpe, 1231, at Verden, in Hanover. In England there was once a brass, which unfortunately disappeared long ago, to an Earl of Bedford, in St. Paul's Church, Bedford, of the year 1208, leaving 1277 as the date of the earliest one.

Latten (Fr. laiton), the material of which brasses were made, was at an early date manufactured in large quantities at Cologne, whence plates of this metal came to be known as cullen (Köln) plates; these were largely exported to other countries, and the Flemish workmen soon attained the greatest proficiency in their engraving. Flemish brasses are usually large and rectangular, having the space between the figure and the marginal inscription filled either by diaper work or by small figures in niches. Brasses vary considerably in size: the matrix of Bishop Beaumont's brass in Durham Cathedral measures about 16 feet by 8 feet, and the memorial to Griel van Ruwescuere, in the chapel of the Lady Superior of the Béguinage at Bruges, is only about 1 foot square. Brazen effigies are more numerous in England in the eastern and southern counties, than in parts more remote from the continent of Europe.

Armorial bearings are displayed in a great variety of ways on monumental brasses, some of which are exhibited in the rubbings selected for illustration. In most cases separate shields are placed above and below the figures. They occur also in the spandrils of canopies and in the shafts and finials of the same, as well as in the centre and at the angles of border-fillets. They naturally predominate in the memorials of warriors, where we find them emblazoned not only on shield and pennon but on the scabbard and ailettes, and on the jupon, tabard, and cuirass also, while crests frequently occur on the tilting-helm. In one case (the brass of Sir Peter Legh, 1527, at Winwick, co. Lancaster) they figure upon the priestly chasuble. Walter Pescod, the merchant of Boston, Lincolnshire, 1398, wears a gown adorned with peascods—a play upon his name; and many a merchant's brass bears his coat of arms and merchant's mark beside, pointing a moral to not a few at the present day. The fifteenth and sixteenth centuries witnessed the greatest profusion in heraldic decoration in brasses, when the tabard and the heraldic mantle were evolved. A good example of the former remains in the parish church of Ormskirk, Lancashire, in the brass commemorating a member of the Scarisbrick family, c. 1500 (Fig. 21). Ladies were accustomed at this time to wear their husband's arms upon the mantle or outer garment and their own upon the kirtle, but the fashion which obtained at a subsequent period was to emblazon the husband's arms on the dexter and their own on the sinister side of the mantle (Fig. 22).

The majority of such monuments, as we behold them now, are destitute of any indications of metals or tinctures, largely owing to the action of the varying degrees of temperature in causing contraction and expansion. Here and there, however, we may still detect traces of their pristine glory. But these matters received due attention from the engraver. To represent or, he left the surface of the brass untouched, except for gilding or perhaps polishing; this universal method has solved many heraldic problems. Lead or some other white metal was inlaid to indicate argent, and the various tinctures were supplied by the excision of a portion of the plate, thereby forming a depression, which was filled up by pouring in some resinous substance of the requisite colour. The various kinds of fur used in armory may be readily distinguished, with the sole exception of vair (argent and azure), which presents the appearance of a row of small upright shields alternating with a similar row reversed.

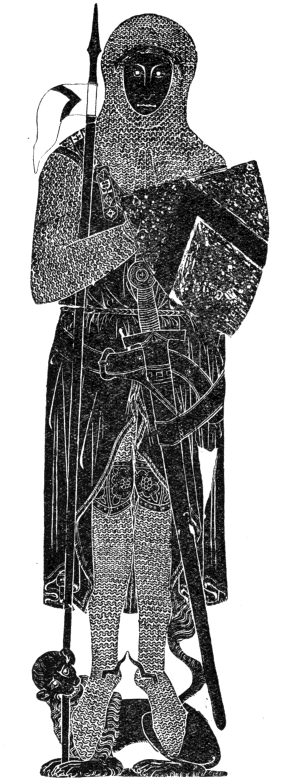

The earliest brass extant in England is that to Sir John D'Aubernoun, the elder (Fig. 23), at Stoke D'Abernon, in Surrey, which carries us back to the year 1277. The simple marginal inscription in Norman-French, surrounding the figure, and each Lombardic capital of which is set in its own matrix, reads: "Sire: John: Daubernoun: Chivaler: Gist: Icy: Deu: De: Sa: Alme: Eyt: Mercy:"[3] In the space between the inscription and the upper portion of the figure were two small shields, of which the dexter one alone remains, charged with the arms of the knight: "Azure, a chevron, or." Sir John D'Aubernoun is represented in a complete panoply of chain mail—his head being protected by a coif de mailles, which is joined to the hauberk or mail shirt, which extends to the hands, having apparently no divisions for the fingers, and being tightened by straps at the wrists. The legs, which are not crossed, are covered by long chausses, or stockings of mail, protected at the knees by poleyns or genouillères of cuir bouilli richly ornamented by elaborate designs. A surcoat, probably of linen, depends from the shoulders to a little below the knees, and is cut away to a point above the knee. This garment is tightly confined (as the creases in the surcoat show) at the waist by a girdle, and over it is passed a guige whereto the long sword is attached. "Pryck" spurs are fixed to the instep, and the feet rest upon a lion, whose mouth grasps the lower portion of a lance. The lance bears a pennon charged with a chevron, as also is the small heater-shaped shield borne on the knight's left arm. The whole composition measures about eight feet by three.

Heraldry figures more prominently in our second illustration, the brass to Sir Roger de Trumpington, 1289 (Fig. 24). This fine effigy lies under the canopy of an altar-tomb, so called, in the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Trumpington, Cambridgeshire. It portrays the knight in armour closely resembling that already described, with these exceptions: the head rests upon a huge heaume, or tilting-helm, attached by a chain to the girdle, and the neck is here protected from side-thrusts by ailettes or oblong plates fastened behind the shoulders, and bearing the arms of Sir Roger. A dog here replaces the lion at the feet, the lance and pennon are absent, and the shield is rounded to the body. On this brass the arms not only occur upon the shield, but also upon the ailettes, and are four times repeated on the scabbard. They afford a good example of "canting" arms: "Azure, crusilly and two trumpets palewise or, with a label of five points in chief, for difference." It is interesting also to notice that the engraver had not completed his task, for the short horizontal lines across the dexter side of the shield indicate his intention of cutting away the surface of the field.

Sir Robert de Setvans (formerly Septvans), whose beautiful brass may be seen at Chartham, Kent, is habited in a surcoat whereon, together with the shield and ailettes, are seven winnowing fans—another instance of canting arms (Fig. 25). This one belongs to a somewhat later date, 1307.

Our next example is a mural effigy to Sir William de Aldeburgh, c. 1360, from the north aisle of Aldborough Church, near Boroughbridge, Yorkshire (Fig. 26). He is attired like the "veray parfite gentil knight" of Chaucer, in a bascinet or steel cap, to which is laced the camail or tippet of chain mail, and a hauberk almost concealed by a jupon, whereon are emblazoned his arms: "Azure, a fess indented argent, between three crosslets botony, or." The first crosslet is charged with an annulet, probably as a mark of cadency. The engraver has omitted the indenture upon the fess, which, however, appears upon the shield. The knight's arms are protected by epaulières, brassarts, coutes, and vambraces; his hands, holding a heart, by gauntlets of steel. An elaborate baldric passes round his waist, from which are suspended, on the left, a cross-hilted sword, in a slightly ornamented scabbard; on the right, a misericorde, or dagger of mercy. The thighs are covered by cuisses—steel plates, here deftly concealed probably by satin or velvet secured by metal studs—the knees by genouillères, the lower leg by jambes, which reveal chausses of mail at the interstices. Sollerets, or long, pointed shoes, whereto are attached rowel spurs, complete his outfit. The figure stands upon a bracket bearing the name "Will's de Aldeburgh."

The parish church of Eastington, Gloucestershire, contains a brass to Elizabeth Knevet, which is illustrated and described by Mr. Cecil T. Davis at p. 117 of his excellent work on the "Monumental Brasses of Gloucestershire."[4] The block (Fig. 27), which presents a good example of the heraldic mantle, has been very kindly placed at my disposal by Mr. Davis. To confine our description to the heraldic portion of the brass, we find the following arms upon the mantle:—

"Quarterly, 1. argent, a bend sable, within a bordure engrailed azure (Knevet); 2. argent, a bend azure, and chief, gules (Cromwell); 3. chequy or and gules, a chief ermine (Tatshall); 4. chequy or and gules, a bend ermine (De Cailly or Clifton); 5. paly of six within a bordure bezanté.... 6. bendy of six, a canton...."[5]

A coat of arms occurs also at each corner of the slab: "Nos. 1 and 4 are on ordinary shields, and 2 and 3 on lozenges. Nos. 1 and 3 are charged with the same bearings as are on her mantle. No. 2, on a lozenge, quarterly, 1. Knevet; 2. Cromwell; 3. Tatshall; 4. Cailli; 5. De Woodstock; 6. paly of six within a bordure; 7. bendy of six, a canton; 8. or, a chevron gules (Stafford); 9. azure, a bend cottised between six lioncels rampant, or (de Bohun). No. 4 similar to No. 1, with the omission of 2 and 3."

In later times thinner plates of metal were employed, a fact which largely contributed to preclude much of the boldness in execution hitherto displayed. A prodigality in shading, either by means of parallel lines or by cross-hatching, also tended to mar the beauty of later work of this kind. Nevertheless there are some good brasses of the Stuart period. These sometimes consist of a single quadrangular plate, with the upper portion occupied by armorial bearings and emblematical figures, the centre by an inscription, and the lower portion by a representation of the deceased, as at Forcett, in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Frequently, however, as at Rotherham and Rawmarsh, in the West Riding of the same county, the inscription is surmounted by a view of the whole family, the father kneeling on a cushion at a fald-stool, with his sons in a similar attitude behind him, and the mother likewise engaged with her daughters on the opposite side, while the armorial insignia find a place on separate shields above.

CHAPTER V

THE COMPONENT PARTS OF AN ACHIEVEMENT

We now come to the science of armory and the rules governing the display of these marks of honour. The term "coat of arms," as we have seen, is derived from the textile garment or "surcoat" which was worn over the armour, and which bore in embroidery a duplication of the design upon the shield. There can be very little doubt that arms themselves are older than the fact of the surcoat or the term "coat of arms." The entire heraldic or armorial decoration which any one is entitled to bear may consist of many things. It must as a minimum consist of a shield of arms, for whilst there are many coats of arms in existence, and many still rightly in use at the present day, to which no crest belongs, a crest in this country cannot lawfully exist without its complementary coat of arms. For the last two certainly, and probably nearly three centuries, no original grant of personal arms has ever been issued without it containing the grant of a crest except in the case of a grant to a woman, who of course cannot bear or transmit a crest; or else in the case of arms borne in right of women or descent from women, through whom naturally no right to a crest could have been transmitted. The grants which I refer to as exceptions are those of quarterings and impalements to be borne with other arms, or else exemplifications following upon the assumption of name and arms which in fact and theory are regrants of previously existing arms, in which cases the regrant is of the original coat with or without a crest, as the case may be, and as the arms theretofor existed. Grants of impersonal arms also need not include a crest. As it has been impossible for the last two centuries to obtain a grant of arms without its necessarily accompanying grant of crest, a decided distinction attaches to the lawful possession of arms which have no crest belonging to them, for of necessity the arms must be at least two hundred years old. Bearing this in mind, one cannot but wonder at the actions of some ancient families like those of Astley and Pole, who, lawfully possessing arms concerning which there is and can be no doubt or question, yet nevertheless invent and use crests which have no authority.

One instance and one only do I know where a crest has had a legitimate existence without any coat of arms. This case is that of the family of Buckworth, who at the time of the Visitations exhibited arms and crest. The arms infringed upon those of another family, and no sufficient proof could be produced to compel their admission as borne of right. The arms were respited for further proof, while the crest was allowed, presumably tentatively, and whilst awaiting the further proof for the arms; no proof, however, was made. The arms and crest remained in this position until the year 1806, when Sir Buckworth Buckworth-Herne, whose father had assumed the additional name of Herne, obtained a Royal Licence to bear the name of Soame in addition to and after those of Buckworth-Herne, with the arms of Soame quarterly with the arms of Buckworth. It then became necessary to prove the right to these arms of Buckworth, and they were accordingly regranted with the trifling addition of an ermine spot upon the chevron; consequently this solitary instance has now been rectified, and I cannot learn of any other instance where these exceptional circumstances have similarly occurred; and there never has been a grant of a crest alone unless arms have been in existence previously.

Whilst arms may exist alone, and the decoration of a shield form the only armorial ensign of a person, such need not be the case; and it will usually be found that the armorial bearings of an ordinary commoner consist of shield, crest, and motto. To these must naturally be added the helmet and mantling, which become an essential to other than an abbreviated achievement when a crest has to be displayed. It should be remembered, however, that the helmet is not specifically granted, and apparently is a matter of inherent right, so that a person would not be in the wrong in placing a helmet and mantling above a shield even when no crest exists to surmount the helmet. The motto is usually to be found but is not a necessity, and there are many more coats of arms which have never been used with a motto than shields which exist without a crest. Sometimes a cri-de-guerre will be found instead of or in addition to a motto. The escutcheon may have supporters, or it may be displayed upon an eagle or a lymphad, &c., for which particular additions no other generic term has yet been coined save the very inclusive one of "exterior ornaments." A coronet of rank may form a part of the achievement, and the shield may be encircled by the "ribbons" or the "circles" or by the Garter, of the various Orders of Knighthood, and by their collars. Below it may depend the badge of a Baronet of Nova Scotia, or of an Order of Knighthood, and added to it may possibly be what is termed a compartment, though this is a feature almost entirely peculiar to Scottish armory. There is also the crowning distinction of a badge; and of all armorial insignia this is the most cherished, for the existing badges are but few in number. The escutcheon may be placed in front of the crosiers of a bishop, the batons of the Earl Marshal, or similar ornaments. It may be displayed upon a mantle of estate, or it may be borne beneath a pavilion. With two more additions the list is complete, and these are the banner and the standard. For these several features of armory reference must be made to the various chapters in which they are treated.

Suffice it here to remark that whilst the term "coat of arms" has through the slipshod habits of English philology come to be used to signify a representation of any heraldic bearing, the correct term for the whole emblazonment is an "achievement," a term most frequently employed to signify the whole, but which can correctly be used to signify anything which a man is entitled to represent of an armorial character. Had not the recent revival of interest in armory taken place, we should have found a firmly rooted and even yet more slipshod declension, for a few years ago the habit of the uneducated in styling anything stamped upon a sheet of note-paper "a crest," was fast becoming stereotyped into current acceptance.

CHAPTER VI

THE SHIELD

The shield is the most important part of the achievement, for on it are depicted the signs and emblems of the house to which it appertains; the difference marks expressive of the cadency of the members within that house; the augmentations of honour which the Sovereign has conferred; the quarterings inherited from families which are represented, and the impalements of marriage; and it is with the shield principally that the laws of armory are concerned, for everything else is dependent upon the shield, and falls into comparative insignificance alongside of it.

Let us first consider the shield itself, without reference to the charges it carries. A shield may be depicted in any fashion and after any shape that the imagination can suggest, which shape and fashion have been accepted at any time as the shape and fashion of a shield. There is no law upon the subject. The various shapes adopted in emblazonments in past ages, and used at the present time in imitation of past usage—for luckily the present period has evolved no special shield of its own—are purely the result of artistic design, and have been determined at the periods they have been used in heraldic art by no other consideration than the particular theory of design that has happened to dominate the decoration, and the means and ends of such decoration of that period. The lozenge certainly is reserved for and indicative of the achievements of the female sex, but, save for this one exception, the matter may be carried further, and arms be depicted upon a banner, a parallelogram, a square, a circle, or an oval; and even then one would be correct, for the purposes of armory, in describing such figures as shields on all occasions on which they are made the vehicles for the emblazonment of a design which properly and originally should be borne upon a shield. Let no one think that a design ceases to be a coat of arms if it is not displayed upon a shield. Many people have thought to evade the authority of the Crown as the arbiter of coat-armour, and the penalties of taxation imposed by the Revenue by using designs without depicting them upon a shield. This little deception has always been borne in mind, for we find in the Royal Warrants of Queen Elizabeth commanding the Visitations that the King of Arms to whom the warrant was addressed was to "correcte, cumptrolle and refourme all mann' of armes, crests, cognizaunces and devices unlawfull or unlawfully usurped, borne or taken by any p'son or p'sons within the same p'vince contary to the due order of the laws of armes, and the same to rev'se, put downe or otherwise deface at his discrecon as well in coote armors, helmes, standerd, pennons and hatchmets of tents and pavilions, as also in plate jewells, pap', parchement, wyndowes, gravestones and monuments, or elsewhere wheresoev' they be sett or placed, whether they be in shelde, schoocheon, lozenge, square, rundell or otherwise howsoev' contarie to the autentiq' and auncient lawes, customes, rules, privileges and orders of armes."

The Act 32 & 33 Victoria, section 19, defines (for the purpose of the taxation it enforced) armorial bearings to mean and include "any armorial bearing, crest, or ensign, by whatever name the same shall be called, and whether such armorial bearing, crest, or ensign shall be registered in the College of Arms or not."

The shape of the shield throughout the rest of Europe has also varied between wide extremes, and at no time has any one particular shape been assigned to or peculiar to any country, rank, or condition, save possibly with one exception, namely, that the use of the cartouche or oval seems to have been very nearly universal with ecclesiastics in France, Spain, and Italy, though never reserved exclusively for their use. Probably this was an attempt on the part of the Church to get away from the military character of the shield. It is in keeping with the rule by which, even at the present day, a bishop or a cardinal bears neither helmet nor crest, using in place thereof his ecclesiastical mitre or tasselled hat, and by which the clergy, both abroad and in this country, seldom made use of a crest in depicting their arms. A clergyman in this country, however, has never been denied the right of using a crest (if he possesses one and chooses to display it) until he reaches episcopal rank. A grant of arms to a clergyman at the present day depicts his achievement with helmet, mantling, and crest in identical form with those adopted for any one else. But the laws of armory, official and amateur, have always denied the right to make use of a crest to bishop, archbishop, and cardinal.

At the present day, if a grant of arms is made to a bishop of the Established Church, the emblazonment at the head of his patent consists of shield and mitre only. The laws of the Church of England, however, require no vow of celibacy from its ecclesiastics, and consequently the descendants of a bishop would be placed in the position of having no crest to display if the bishop and his requirements were alone considered. So that in the case of a grant to a bishop the crest is granted for his descendants in a separate clause, being depicted by itself in the body of the patent apart from the emblazonment "in the margin hereof," which in an ordinary patent is an emblazonment of the whole achievement. A similar method is usually adopted in cases in which the actual patentee is a woman, and where, by the limitations attached to the patent being extended beyond herself, males are brought in who will bear the arms granted to the patentee as their pronominal arms. In these cases the arms of the patentee are depicted upon a lozenge at the head of the patent, the crest being depicted separately elsewhere.

Whilst shields were actually used in warfare the utilitarian article largely governed the shape of the artistic representation, but after the fifteenth century the latter gradually left the beaten track of utility and passed wholly into the cognisance of art and design. The earliest shape of all is the long, narrow shape, which is now but seldom seen. This was curved to protect the body, which it nearly covered, and an interesting example of this is to be found in the monumental slab of champlevé enamel, part of the tomb of Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou (Fig. 28), the ancestor of our own Royal dynasty of Plantagenet, who died in the year 1150. This tomb was formerly in the cathedral of Le Mans, and is now in the museum there. I shall have occasion again to refer to it. The shield is blue; the lions are gold.

Other forms of the same period are found with curved tops, in the shape of an inverted pear, but the form known as the heater-shaped shield is to all intents and purposes the earliest shape which was used for armorial purposes.

The church of St. Elizabeth at Marburg, in Hesse, affords examples of shields which are exceedingly interesting, inasmuch as they are original and contemporary even if only pageant shields. Those which now remain are the shields of the Landgrave Konrad (d. 1241) of Thuringia and of Henry of Thuringia (d. 1298). The shield of the former (see Fig. 29) is 90 centimetres high and 74 wide. Konrad was Landgrave of Thuringia and Grand Master of the Teutonic Order of Knighthood. His arms show the lion of Thuringia barry of gules and argent on a field of azure, and between the hind feet a small shield, with the arms of the Teutonic Order of Knights. The only remains of the lion's mane are traces of the nails. The body of the lion is made of pressed leather, and the yellow claws have been supplied with a paint-brush. A precious stone probably represented the eye.

The making and decorating of the shields lay mostly in the hands of the herald painters, known in Germany as Schilter, who, in addition to attending to the shield and crest, also had charge of all the riding paraphernalia, because most of the articles comprised therein were heraldically decorated. Many of these shield-workers' fraternities won widespread fame for themselves, and enjoyed great consideration at that time.

Thus the "History of a Celebrated Painters' Guild on the Lower Rhine" tells us of costly shields which the shield-workers of Paris had supplied, 1260, &c. Vienna, too, was the home of a not unimportant shield-workers' guild, and the town archives of Vienna contain writings of the fifteenth century treating of this subject. For instance, we learn that in an order of St. Luke's parish, June 28, 1446, with regard to the masterpiece of a member of the guild—

"Item, a shield-worker shall make four new pieces of work with his own hand, a jousting saddle, a leather apron, a horse's head-piece, and a jousting shield, that shall he do in eight weeks, and must be able to paint it with his own hand, as Knight and man-at-arms shall direct."

The shield was of wood, covered with linen or leather, the charges in relief and painted. Leather plastic was very much esteemed in the early Middle Ages. The leather was soaked in oil, and pressed or beaten into shape. Besides piecing and leather plastic, pressed linen (linen dipped in chalk and lime) was also used, and a kind of tempera painting on a chalk background. After the shield was decorated with the charges, it was frequently strengthened with metal clasps, or studs, particularly those parts which were more especially exposed to blows and pressure. These clasps and nails originally had no other object than to make the shield stronger and more durable, but later on their nature was misunderstood; they were treated and used as genuine heraldic charges, and stereotyped into hereditary designs. The long strips with which the edge was bound were called the "frame" (Schildgestell), the clasps introduced in the middle of the shield the "buckle" or "umbo" (see on Fig. 28), from which frequently circularly arranged metal snaps reached the edge of the shield. This latter method of strengthening the shield was called the "Buckelrîs," a figure which was afterwards frequently employed as a heraldic charge, and is known in Germany by the name of Lilienhaspel (Lily-staple) or Glevenrad, or, as we term it in England, the escarbuncle.

In the second half of the fourteenth century, when the tournament provided the chief occasion for the shield, the jousting-shield, called in Germany the Tartsche or Tartscher, came into use, and from this class of shield the most varied shapes were gradually developed. These Tartschen were decidedly smaller than the earlier Gothic shields, being only about one-fifth of a man's height. They were concave, and had on the side of the knight's right hand a circular indentation. This was the spear-rest, in which to place the tilting-spear. The later art of heraldic decoration symmetrically repeated the spear-rest on the sinister side of the shield, and, by so doing, transformed a useful fact into a matter of mere artistic design. Doubtless it was argued that if indentations were correct at one point in the outline they were correct at another, and when once the actual fact was departed from the imagination of designers knew no limits. But if the spear-rest as such is introduced into the outline of a shield it should be on the dexter side.

Reverting to the various shapes of shield, however, the degeneration is explained by a remark of Mr. G. W. Eve in the able book which he has recently published under the title of "Decorative Heraldry," in which, alluding to heraldic art in general, he says (p. 235):—

"With the Restoration heraldry naturally became again conspicuous, with the worst form of the Renaissance character in full sway, the last vestiges of the Gothic having disappeared. Indeed, the contempt with which the superseded style was regarded amounted to fanaticism, and explains, in a measure, how so much of good could be relinquished in favour of so weak a successor."

Later came the era of gilded embellishments, of flowing palms, of borders decorated with grinning heads, festoons of ribbon, and fruit and flowers in abundance. The accompanying examples are reproduced from a book, Knight and Rumley's "Heraldry." The book is not particularly well known to the public, inasmuch as its circulation was entirely confined to heraldic artists, coach-painters, engravers, and die-sinkers. Amongst these handicraftsmen its reputation was and is great. With the school of design it adopted, little or no sympathy now exists, but a short time ago (how short many of those who are now vigorous advocates of the Gothic and mediæval styles would be startled to realise were they to recognise actual facts) no other style was known or considered by the public. As examples of that style the plates of Knight and Rumley were admittedly far in advance of any other book, and as specimens of copperplate engraving they are superb. Figs. 30, 31, and 32 show typical examples of escutcheons from Knight and Rumley; and as the volume was in the hands of most of the heraldic handicraftsmen, it will be found that this type of design was constantly to be met with. The external decoration of the shield was carried to great lengths, and Fig. 31 found many admirers and users amongst the gallant "sea-dogs" of the kingdom. In fact, so far was the idea carried that a trophy of military weapons was actually granted by patent as part of the supporters of the Earl of Bantry. Fig. 30, from the same source, is the military equivalent. These plates are interesting as being some of the examples from which most of the heraldic handicraft of a recent period was adapted. The official shield eventually stereotyped itself into a shape akin to that shown in Fig. 32, though nowadays considerable latitude is permitted. For paintings which are not upon patents the design of the shield rests with the individual taste of the different officers of arms, and recently some of the work for which they have been responsible has reached a high standard judged even by the strictest canons of art. In Scotland, until very recently, the actual workmanship of the emblazonments which were issued from Lyon Office was so wretchedly poor that one is hardly justified in taking them into consideration as a type. With the advent into office of the present Lyon King of Arms (Sir James Balfour Paul), a complete change has been made, and both the workmanship and design of the paintings upon the patents of grant and matriculation, and also in the Lyon Register, have been examples of everything that could be desired.

CHAPTER VII

THE FIELD OF A SHIELD AND THE HERALDIC TINCTURES

The shield itself and its importance in armory is due to its being the vehicle whereon are elaborated the pictured emblems and designs which constitute coat-armour. It should be borne in mind that theoretically all shields are of equal value, saving that a shield of more ancient date is more estimable than one of recent origin, and the shield of the head of the house takes precedence of the same arms when differenced for a younger member of the family. A shield crowded with quarterings is interesting inasmuch as each quartering in the ordinary event means the representation through a female of some other family or branch thereof. But the real value of such a shield should be judged rather by the age of the single quartering which represents the strict male descent male upon male, and a simple coat of arms without quarterings may be a great deal more ancient and illustrious than a shield crowded with coat upon coat. A fictitious and far too great estimation is placed upon the right to display a long string of quarterings. In reality quarterings are no more than accidents, because they are only inherited when the wife happens to be an heiress in blood. It is quite conceivable that there may be families, in fact there are such families, who are able to begin their pedigrees at the time of the Conquest, and who have married a long succession of noble women, all of the highest birth, but yet none of whom have happened to be heiresses. Consequently the arms, though dating from the earliest period at which arms are known, would remain in their simple form without the addition of a solitary quartering. On the other hand, I have a case in mind of a marriage which took place some years ago. The husband is the son of an alien whose original position, if report speaks truly, was that of a pauper immigrant. His wealth and other attributes have placed him in a good social position; but he has no arms, and, as far as the world is aware, no ancestry whatever. Let us now consider his wife's family. Starting soon after the Conquest, its descendants obtained high position and married heiress after heiress, and before the commencement of this century had amassed a shield of quarterings which can readily be proved to be little short of a hundred in number. Probably the number is really much greater. A large family followed in one generation, and one of the younger sons is the ancestor of the aforesaid wife. But the father of this lady never had any sons, and though there are many males of the name to carry on the family in the senior line and also in several younger branches, the wife, by the absence of brothers, happens to be a coheir; and as such she transmits to her issue the right to all the quarterings she has inherited. If the husband ever obtains a grant of arms, the date of them will be subsequent to the present time; but supposing such a grant to be obtained, the children will inevitably inherit the scores of quarterings which belong to their mother. Now it would be ridiculous to suppose that such a shield is better or such a descent more enviable than the shield of a family such as I first described. Quarterings are all very well in their way, but their glorification has been carried too far.

A shield which displays an augmentation is of necessity more honourable than one without. At the same time no scale of precedence has ever been laid down below the rank of esquires; and if such precedence does really exist at all, it can only be according to the date of the grant. Here in England the possession of arms carries with it no style or title, and nothing in his designation can differentiate the position of Mr. Scrope of Danby, the male descendant of one of the oldest families in this country, whose arms were upheld in the Scrope and Grosvenor controversy in 1390, or Mr. Daubeney of Cote, from a Mr. Smith, whose known history may have commenced at the Foundling Hospital twenty years ago. In this respect English usage stands apart, for whilst a German is "Von" and a Frenchman was "De," if of noble birth, there is no such apparent distinction in England, and never has been. The result has been that the technical nobility attaching to the possession of arms is overlooked in this country. On the Continent it is usual for a patent creating a title to contain a grant of the arms, because it is recognised that the two are inseparable. This is not now the case in England, where the grant of arms is one thing and the grant of the title another, and where it is possible, as in the case of Lord St. Leonards, to possess a peerage without ever having obtained the first step in rank, which is nobility or gentility.

The foregoing is in explanation of the fact that except in the matter of date all shields are equal in value.

So much being understood, it is possible to put that consideration on one side, and speaking from the artistically technical point of view, the remark one often hears becomes correct, that the simpler a coat of arms the better. The remark has added truth from the fact that most ancient coats of arms were simple, and many modern coats are far from being worthy of such a description.

A coat of arms must consist of at least one thing, to wit, the "field." This is equivalent in ordinary words to the colour of the ground of the shield. A great many writers have asserted that every coat of arms must consist of at least the field, and a charge, though most have mentioned as a solitary exception the arms of Brittany, which were simply "ermine." A plain shield of ermine (Fig. 33) was borne by John of Brittany, Earl of Richmond (d. 1399), though some of his predecessors had relegated the arms of Brittany to a "quarter ermine" upon more elaborate escutcheons (Fig. 61). This idea as to arms of one tincture was, however, exploded in Woodward and Burnett's "Treatise on Heraldry," where no less than forty different examples are quoted. The above-mentioned writer continues: "There is another use of a plain red shield which must not be omitted. In the full quartered coat of some high sovereign princes of Germany—Saxony (duchies), Brandenburg (Prussia), Bavaria, Anhalt—appears a plain red quartering; this is known as the Blut Fahne or Regalien quarter, and is indicative of Royal prerogatives. It usually occupies the base of the shield, and is often diapered."