As much as fifteen hundred-weight of beans per acre have been gathered from trees in North Queensland; and for years the average was ten hundred-weight per acre. After thirty years of cultivation, no signs of disease have appeared. At late as 1920, the government was proposing to make advances of fourteen cents a pound upon coffee in the parchment to encourage the development of the industry to a point where it would be possible for local coffee growers to capture at least the bulk of the commonwealth's import coffee trade of 2,605,240 pounds.

Coffee grows well in most all the islands of the Pacific Ocean, and in some of them, as in the Philippines and Hawaii, the industry in past years, reached considerable importance.

Hawaii. Coffee has been grown in Hawaii since 1825, from plants brought from Brazil. It has also been said that seed was brought by Vancouver, the British navigator, on his Pacific exploration voyage, 1791–94. Not, however, until 1845 was an official record made of the crop, which was then 248 pounds. The first plantations, started on the low levels, near the sea, did not do well; and it was not until the trees were planted at elevations of from 1,000 to 3,000 feet above sea-level that better returns were obtained.

Coffee is grown on all the islands of the group, but nowhere to any great extent except on Hawaii, which produces ninety-five percent of the entire crop. Next in importance, though far behind, is the island of Oahu. On Hawaii there are four principal coffee districts, Kona, Hamakua, Puna, and Olaa. About four-fifths of the total output of the islands is produced in Kona. At one time there were considerable coffee areas in Maui and Kauai, but sugar cane eventually there took the place of coffee.

The Kona coffee district extends for many miles along the western slope of the island of Hawaii and around famous Kealakekua Bay. The soil is volcanic, and even rocky; but coffee trees flourish surprisingly well among the rocks, and are said to bear a bean of superior quality.

Coffee trees in Kona are planted principally in the open, though sometimes they are shaded by the native kukui trees. They are grown from seed in nurseries; and the seedlings, when one year old, are transplanted in regular lines nine feet apart. In two years a small crop is gathered, yielding from five to twelve bags of cleaned coffee per acre. At three years of age the trees produce from eight to twenty bags of cleaned coffee per acre, and from that time they are fully matured. The ripening season is between September and January, and there are two principal pickings. Many of the trees are classed as wild; that is, they are not topped, and are cultivated in an irregular manner and are poorly cared for; but they yield 700 or 800 pounds per acre. The fruit ripens very uniformly, and is picked easily and at slight expense.

It is calculated that in the Hawaiian group more than 250,000 acres of good coffee land are available and about 200,000 acres more of fair quality. Comparatively little of this possible acreage has been put to use. According to the census of 1889, there were then 6,451 acres devoted to coffee, having, young and old, 3,225,743 bearing trees. The yield, in that census year, was 2,297,000 pounds, of which 2,112,650 pounds were credited to Hawaii, the small remainder coming from Maui, Oahu, Kauai, and Molokai.

A blight in 1855–56 set back the industry, many plantations being ruined and then given over to sugar cane. After the blight had disappeared, the plantations were re-established, and prosperity continued for years. Following the American occupation of the islands in 1898, came another period of depression. With the loss of the protective tariff that had existed, prices fell to an unremunerativte figure; and the more profitable sugar cane was taken up again. After 1912, the increased demand for coffee, with higher prices, led again to hopes for the future of the industry. Planting was encouraged; and it has been demonstrated that from lands well selected and intelligently cultivated it is possible to have a yield of from 1,200 to 2,100 pounds per acre. Improvements have also been made in pulping and milling facilities. Many of the plantations are cultivated by Japanese labor.

Exports of coffee from Hawaii to the principal countries of the world in 1920 were 2,573,300 pounds.

Philippine Islands. Spanish missionaries from Mexico are said to have carried the coffee plant to the Philippine Islands in the latter part of the eighteenth century. At first it was cultivated in the province of La Laguna; but afterward other provinces, notably Batangas and Cavite, took it up; and in a short time the industry was one of the most important in the islands. The coffee was of the arabica variety. In the middle of the eighteenth century, and after, the industry had a position of importance; several provinces produced profitable crops that contributed much to the wealth of the communities where the berry was cultivated. In those days the city of Yipa was an important trading center. In the period of its prime Philippine coffee enjoyed fine repute, especially in Spain, Great Britain, and China (at Hong Kong), those three countries being the largest consumers. At one time—in 1883 and 1884—the annual export was 16,000,000 pounds, which demonstrates the importance of the industry at the peak of its prosperity. The leaf blight appeared on the island about 1889, causing destruction from which there has not yet been complete recovery. The export of 3,086 pounds in 1917 shows the depths into which the industry had fallen.

The Bureau of Agriculture at Manila announced in 1915 that an effort was to be made to re-habilitate the coffee industry of the islands. Nothing came of the effort, which died a-borning. Since then, several attempts to introduce disease-resisting varieties of coffee from Java have failed because of lack of interest on the part of the natives.

Despite the misfortunes that have overwhelmed it in the past and are now retarding its growth, it is still believed that the industry in these islands may be re-habilitated. Conditions of soil and climate are favorable; land and labor are cheap, abundant, and dependable: railroads run into the best coffee regions, and good cart roads are in process of construction. Some plantations of consequence are still in existence, and serious consideration is being given to their development and to increasing their number.

Guam. Coffee is one of the commonest wild plants on the little island of Guam. It grows around the houses like shade trees or flowering shrubs, and nearly every family cultivates a small patch. Climate and soil are favorable to it; and it flourishes, with abundant crops, from the sea-level to the tops of the highest hills. The plants are set in straight rows, from three and a half to seven feet apart, and are shaded by banana trees or by cocoanut leaves stuck in the ground. There is no production for export, scarcely enough for home consumption.

Other Pacific Islands. Other islands of the Pacific do not loom large in coffee growing, though New Caledonia gives promise as a producer, exporting 1,248,024 pounds in 1916, most of which was robusta. Tahiti produces a fair coffee, but in no commercial quantity. In the Samoan group there are plantations, small in number, in size, and in amount of production. Several islands of the Fiji group are said to be well adapted to coffee, but little is grown there and none for export.

Owner's Residence Adjoining Drying Grounds on One of the Large Estates

Owner's Residence Adjoining Drying Grounds on One of the Large Estates

Chapter XXI

PREPARING GREEN COFFEE FOR MARKET

Early Arabian methods of preparation—How primitive devices were replaced by modern methods—A chronological story of the development of scientific plantation machinery, and the part played by British and American inventors—The marvelous coffee package, one of the most ingenious in all nature—How coffee is harvested—Picking—Preparation by the dry and the wet methods—Pulping—Fermentation and washing—Drying—Hulling; or peeling, and polishing—Sizing, or grading—Preparation methods of different countries

La Roque[316], in his description of the ancient coffee culture, and the preparation methods as followed in Yemen, says that the berries were permitted to dry on the trees. When the outer covering began to shrivel, the trees were shaken, causing the fully matured fruits to drop upon cloths spread to receive them. They were next exposed to the sun on drying-mats, after which they were husked by means of wooden or stone rollers. The beans were given a further drying in the sun, and then were submitted to a winnowing process, for which large fans were used.

Development of Plantation Machinery

The primitive methods of the original Arab planters were generally followed by the Dutch pioneers, and later by the French, with slight modifications. As the cultivation spread, necessity for more effective methods of handling the ripened fruit mothered inventions that soon began to transform the whole aspect of the business. Probably the first notable advance was in curing, when the West Indian process, or wet method, of cleaning the berries was evolved.

About the time that Brazil began the active cultivation of coffee, William Panter was granted the first English patent on a "mill for husking coffee." This was in 1775. James Henckel followed with an English patent, granted in 1806, on a coffee drier, "an invention communicated to him by a certain foreigner." The first American to enter the lists was Nathan Reed of Belfast, Me., who in 1822 was granted a United States patent on a coffee huller. Roswell Abbey obtained a United States patent on a huller in 1825; and Zenos Bronson, of Jasper County, Ga., obtained one on another huller in 1829. In the next few years many others followed.

John Chester Lyman, in 1834, was granted an English patent on a coffee huller employing circular wooden disks, fitted with wire teeth. Isaac Adams and Thomas Ditson of Boston brought out improved hullers in 1835; and James Meacock of Kingston, Jamaica, patented in England, in 1845, a self-contained machine for pulping, dressing, and sorting coffee.

William McKinnon began, in 1840, the manufacture of coffee plantation machinery at the Spring Garden Iron Works, founded by him in 1798 in Aberdeen, Scotland. He died in 1873; but the business continues as Wm. McKinnon & Co., Ltd.

About 1850 John Walker, one of the pioneer English inventors of coffee-plantation machinery, brought out in Ceylon his cylinder pulper for Arabian coffee. The pulping surface was made of copper, and was pierced with a half-moon punch that raised the cut edges into half circles.

The next twenty years witnessed some of the most notable advances in the development of machinery for plantation treatment, and served to introduce the inventions of several men whose names will ever be associated with the industry.

John Gordon & Co. began the manufacture in London of the line of plantation machinery still known around the world as "Gordon make" in 1850; and John Gordon was granted an English patent on his improved coffee pulper in 1859.

Robert Bowman Tennent obtained English (1852) and United States (1853) patents on a two-cylinder pulper.

George L. Squier began the manufacture of plantation machinery in Buffalo, N.Y., in 1857. He was active in the business until 1893, and died in 1910. The Geo. L. Squier Manufacturing Co. still continues as one of the leading American manufacturers of coffee-plantation machinery.

Marcus Mason, an American mechanical engineer in San José, Costa Rica, invented (1860) a coffee pulper and cleaner which became the foundation stone of the extensive plantation-machinery business of Marcus Mason & Co., established in 1873 at Worcester, Mass.

John Walker was granted (1860) an English patent on a disk pulper in which the copper pulping surface was punched, or knobbed, by a blind punch that raised rows of oval knobs but did not pierce the sheet, and so left no sharp edges. During Ceylon's fifty years of coffee production, the Walker machines played an important part in the industry. They are still manufactured by Walker, Sons & Co., Ltd., of Colombo, and are sold to other producing countries.

Alexius Van Gulpen began the manufacture of a green-coffee-grading machine at Emmerich, Germany, in 1860.

Following Newell's United States patents of 1857–59, sixteen other patents were issued on various types of coffee-cleaning machines, some designed for plantation use, and some for treating the beans on arrival in the consuming countries.

James Henry Thompson, of Hoboken, and John Lidgerwood were granted, in 1864, an English patent on a coffee-hulling machine. William Van Vleek Lidgerwood, American chargé d'affaires at Rio de Janeiro, was granted an English patent on a coffee hulling and cleaning machine in 1866. The name Lidgerwood has long been familiar to coffee planters. The Lidgerwood Manufacturing Co., Ltd., has its headquarters in London, with factory in Glasgow. Branch offices are maintained at Rio de Janeiro, Campinas, and in other cities in coffee-growing countries.

Probably the name most familiar to coffee men in connection with plantation methods is Guardiola. It first appears in the chronological record in 1872, when J. Guardiola, of Chocola, Guatemala, was granted several United States patents on machines for pulping and drying coffee. Since then, "Guardiola" has come to mean a definite type of rotary drying machine that—after the original patent expired—was manufactured by practically all the leading makers of plantation machinery. José Guardiola obtained additional United States patents on coffee hullers in 1886.

William Van Vleek Lidgerwood, Morristown, N.J., was granted an English patent on an improved coffee pulper in 1875.

Several important cleaning and grading machinery patents were granted by the United States (1876–1878) to Henry B. Stevens, who assigned them to the Geo. L. Squier Manufacturing Co., Buffalo, N.Y. One of them was on a separator, in which the coffee beans were discharged from the hopper in a thin stream upon an endless carrier, or apron, arranged at such an inclination that the round beans would roll by force of gravity down the apron, while the flat beans would be carried to the top.

C.F. Hargreaves, of Rio de Janeiro, was granted an English patent on machinery for hulling, polishing, and separating coffee, in 1879.

The first German patent on a coffee drying apparatus was granted to Henry Scolfield, of Guatemala, in 1880.

In 1885 Evaristo Conrado Engelberg of Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil, invented an improved coffee huller which, three years later, was patented in the United States. The Engelberg Huller Co. of Syracuse, N.Y., was organized the same year (1888) to make and to sell Engelberg machines.

Walker Sons & Co., Ltd., began, in 1886, experimenting in Ceylon with a Liberian disk pulper that was not fully perfected until twelve years later.

Another name, that has since become almost as well known as Guardiola, appears in the record in 1891. It is that of O'Krassa. In that year R.F.E. O'Krassa of Antigua, Guatemala, was granted an English patent on a coffee pulper. Additional patents on washing, hulling, drying, and separating machines were issued to Mr. O'Krassa in England and in the United States in 1900, 1908, 1911, 1912, and 1913.

The Fried. Krupp A.G. Grusonwerk, Magdeburg-Buckau, Germany, began the manufacture of coffee plantation machines about 1892. Among others it builds coffee pulpers and hulling and polishing machines of the Anderson (Mexican) and Krull (Brazilian) types.

Additional United States patents were granted in 1895 to Marcus Mason, assignor to Marcus Mason & Co., New York, on machines for pulping and polishing coffee. Douglas Gordon assigned patents on a coffee pulper and a coffee drier to Marcus Mason & Co. in 1904–05.

The names of Jules Smout, a Swiss, and Don Roberto O'Krassa, of Guatemala, are well known to coffee planters the world over because of their combined peeling and polishing machines.

The Huntley Manufacturing Co., Silver Creek, N.Y., began in 1896 the manufacture of the Monitor line of coffee-grading-and-cleaning machines.

The Marvelous Coffee Package

It is doubtful if in all nature there is a more cunningly devised food package than the fruit of the coffee tree. It seems as if Good Mother Nature had said: "This gift of Heaven is too precious to put up in any ordinary parcel. I shall design for it a casket worthy of its divine origin. And the casket shall have an inner seal that shall safeguard it from enemies, and that shall preserve its goodness for man until the day when, transported over the deserts and across the seas, it shall be broken open to be transmuted by the fires of friendship, and made to yield up its aromatic nectar in the Great Drink of Democracy."

To this end she caused to grow from the heart of the jasmine-like flower, that first herald of its coming, a marvelous berry which, as it ripens, turns first from green to yellow, then to reddish, to deep crimson, and at last to a royal purple.

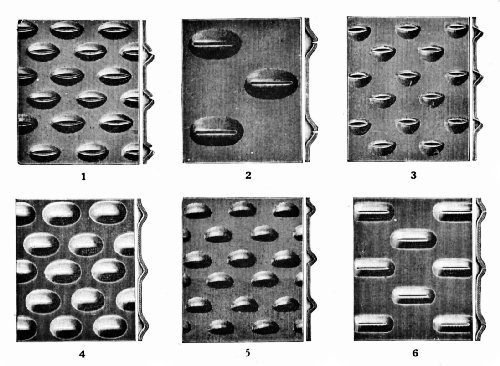

Specimens of Copper Covers for Pulper Cylinders

Specimens of Copper Covers for Pulper Cylinders1—For Arabian coffee (Coffea arabica). 2—For Liberian coffee (Coffea liberica). 3—Also for Arabian. 4—For Coffea canephora. 5—For Coffea robusta. 6—For larger Arabian, and for Coffea Maragogipe.

The coffee fruit is very like a cherry, though somewhat elongated and having in its upper end a small umbilicus. But mark with what ingenuity the package has been constructed! The outer wrapping is a thin, gossamer-like skin which encloses a soft pulp, sweetish to the taste, but of a mucilaginous consistency. This pulp in turn is wrapped about the inner-seal—called the parchment, because of its tough texture. The parchment encloses the magic bean in its last wrapping, a delicate silver-colored skin, not unlike fine spun silk or the sheerest of tissue papers. And this last wrapping is so tenacious, so true to its guardianship function, that no amount of rough treatment can dislodge it altogether; for portions of it cling to the bean even into the roasting and grinding processes.

Pulping House and Fermentation Tanks, Costa Rica

COFFEE PREPARATION IN CENTRAL AND SOUTH AMERICA

Coffee is said to be "in the husk," or "in the parchment," when the whole fruit is dried; and it is called "hulled coffee" when it has been deprived of its hull and peel. The matter forming the fruit, called the coffee berry, covers two thin, hard, oval seed vessels held together, one to the other, by their flat sides. These seed vessels, when broken open, contain the raw coffee beans of commerce. They are usually of a roundish oval shape, convex on the outside, flat inside, marked longitudinally in the center of the flat side with a deep incision, and wrapped in the thin pellicle known as the silver skin. When one of the two seeds aborts, the remaining one acquires a greater size, and fills the interior of the fruit, which in that case, of course, has but one cellule. This abortion is common in the arabica variety, and produces a bean formerly called gragé coffee, but now more commonly known as peaberry, or male berry.

The various coverings of the coffee beans are almost always removed on the plantations in the producing countries. Properly to prepare the raw beans, it is necessary to remove the four coverings—the outer skin, the sticky pulp, the parchment, or husk, and the closely adhering silver skin.

There are two distinct methods of treating the coffee fruits, or "cherries." One process, the one that until recent years was in general use throughout the world, and is still in many producing countries, is known as the dry method. The coffee prepared in this way is sometimes called "common," "ordinary," or "natural," to distinguish it from the product that has been cleaned by the wet or washed method. The wet method, or, as it is sometimes designated, the "West Indian process" (W.I.P.) is practised on all the large modern plantations that have a sufficient supply of water.

In the wet process, the first step is called pulping; the second is fermentation and washing; the third is drying; the fourth is hulling or peeling; and the last, sizing or grading. In the dry process, the first step is drying; the second hulling; and the last, sizing or grading.

Harvesting

The coffee cherry ripens about six to seven months after the tree has flowered, or blossomed; and becomes a deep purplish-crimson color. It is then ready for picking. The ripening season varies throughout the world, according to climate and altitude. In the state of São Paulo, Brazil, the harvesting season lasts from May to September; while in Java, where three crops are produced annually, harvesting is almost a continuous process throughout the year. In Colombia the harvesting seasons are March and April, and November and December. In Guatemala the crops are gathered from October through December; in Venezuela, from November through March. In Mexico the coffee is harvested from November to January; in Haiti the harvest extends from November to March; in Arabia, from September to March; in Abyssinia, from September through November. In Uganda, Africa, there are two main crops, one ripening in March and the other in September, and picking is carried on during practically every month except December and January. In India the fruit is ready for harvesting from October to January.

Tandem Coffee Pulper of English Make

Being a combination of a Bon-Accord-Valencia pulper with a Bon-Accord repassing machine

Picking

The general practise throughout the world has been to hand-pick the fruit; although in some countries the cherries are allowed to become fully ripe on the trees, and to fall to the ground. The introduction of the wet method of preparation, indeed, has made it largely unnecessary to hand-pick crops; and the tendency seems to be away from this practise on the larger plantations. If the berries are gathered promptly after dropping, the beans are not injured, and the cost of harvesting is reduced.

The picking season is a busy time on a large plantation. All hands join in the work—men, women and children; for it must be rushed. Over-ripe berries shrink and dry up. The pickers, with baskets slung over their shoulders, walk between the rows, stripping the berries from the trees, using ladders to reach the topmost branches, and sometimes even taking immature fruit in their haste to expedite the work. About thirty pounds is considered a fair day's work under good conditions. As the baskets are filled, they are emptied at a "station" in that particular unit of the plantation; or, in some cases, directly into wagons that keep pace with the pickers. The coffee is freed as much as possible of sticks, leaves, etc., and is then conveyed to the preparation grounds.

A space of several acres is needed for the various preparation processes on the larger plantations; the plant including concrete-surfaced drying grounds, large fermentation tanks, washing vats, mills, warehouses, stables, and even machine shops. In Mexico this place is known as the beneficio.

Washed and Unwashed Coffee

Where water is plenty, the ripe coffee cherries are fed by a stream of water into a pulping machine which breaks the outer skins, permitting the pulpy matter enveloping the beans to be loosened and carried away in further washings. It is this wet separation of the sticky pulp from the beans, instead of allowing it to dry on them, to be removed later with the parchment in the hulling operation, that makes the distinction between washed and unwashed coffees. Where water is scarce the coffees are unwashed.

Either method being well done, does washing improve the strength and flavor? Opinions differ. The soil, altitude, climatic influences, and cultivation methods of a country give its coffee certain distinctive drinking qualities. Washing immensely improves the appearance of the bean; it also reduces curing costs. Generally speaking, washed coffees will always command a premium over coffees dried in the pulp.

Whether coffee is washed or not, it has to be dried; and there is a kind of fermentation that goes on during washing and drying, about which coffee planters have differing ideas, just as tea planters differ over the curing of tea leaves. Careful scientific study is needed to determine how much, if any, effect this fermentation has on the ultimate cup value.

Preparation by the Dry Method

The dry method of preparing the berries is not only the older method, but is considered by some operators as providing a distinct advantage over the wet process, since berries of different degrees of ripeness can be handled at the same time. However, the success of this method is dependent largely on the continuance of clear warm weather over quite a length of time, which can not always be counted on.

In this process the berries are spread in a thin layer on open drying grounds, or barbecues, often having cement or brick surfaces. The berries are turned over several times a day in order to permit the sun and wind thoroughly to dry all portions. The sun-drying process lasts about three weeks; and after the first three days of this period, the berries must be protected from dews and rains by covering them with tarpaulins, or by raking them into heaps under cover. If the berries are not spread out, they heat, and the silver skin sticks to the coffee bean, and frequently discolors it. When thoroughly dry, the berries are stored, unless the husks (outer skin and inner parchment) are to be removed at once. Hot air, steam, and other artificial drying methods take the place of natural sun-drying on some plantations.

In the dry method, the husks are removed either by hand (threshing and pounding in a mortar, on the smaller plantations) or by specially constructed machinery, known as hulling machines.

The Wet Method—Pulping

The wet method of preparation is the more modern form, and is generally practised on the larger plantations that have a sufficient supply of water, and enough money to instal the quite extensive amount of machinery and equipment required. It is generally considered that washing results in a better grade of bean.

In this method the cherries are sometimes thrown into tanks full of water to soak about twenty-four hours, so as to soften the outer skins and underlying pulp to a condition that will make them easily removable by the pulping machine—the idea being to rub away the pulp by friction without crushing the beans.

On the larger plantations, however, the coffee cherries are dumped into large concrete receiving tanks, from which they are carried the same day by streams of running water directly into the hoppers of the pulping machines.

At least two score of different makes of pulping machines are in use in the various coffee-growing countries. Pulpers are made in various sizes, from the small hand-operated machine to the large type driven by power; and in two general styles—cylinder, and disk.

The cylinder pulper, the latest style—suggesting a huge nutmeg-grater—consists of a rotary cylinder surrounded with a copper or brass cover punched with bulbs. These bulbs differ in shape according to the species, or variety, of coffee to be treated—arabica, liberica, robusta, canephora, or what not. The cylinder rotates against a breast with pulping edges set at an angle. The pulping is effected by the rubbing action of the copper cover against the edges, or ribs, of the breast. The cherries are subjected to a rubbing and rolling motion, in the course of which the two parchment-covered beans contained in the majority of the cherries become loosened. The pulp itself is carried by the cover and is discharged through a pulp shoot, while the pulped coffee is delivered through holes on the breast. Cylinder machines vary in capacity from 400 pounds (hand power) to 4,800 pounds (motive power) per hour.

Some cylinder pulpers are double, being equipped with rotary screens or oscillating sieves, that segregate the imperfectly pulped cherries so that they may be put through again. Pulpers are also equipped with attachments that automatically move the imperfectly pulped material over into a repassing machine for another rubbing. Others have attachments partially to crush the cherries before pulping.

The breasts in cylinder machines are usually made with removable steel ribs; but in Brazil, Nicaragua, and other countries, where, owing to the short season and scarcity of labor, the planters have to pick, simultaneously, green, ripe, and over-ripe (dry) cherries, rubber breasts are used.

The Squier-Guardiola Coffee Drier, With Direct-Fire Heater

BRITISH AND AMERICAN COFFEE DRIERS—GUARDIOLA SYSTEM

There are numerous makes of coffee driers based upon the original invention of José Guardiola of Chocola, Guatemala. In the two illustrated above both direct-fire heat and steam heat may be utilized

The disk pulper (the earliest type, having been in use more than seventy years) is the style most generally used in the Dutch East Indies and in some parts of Mexico. The results are the same as those obtained with the cylindrical pulper. The disk machine is made with one, two, three, or four vertical iron disks, according to the capacity desired. The disks are covered on both sides with a copper plate of the same shape, and punched with blind punches. The pulping operation takes place between the rubbing action of the blind punches, or bulbs, on the copper plates and the lateral pulping bars fitted to the side cheeks. As in the cylinder pulper, the distance between the surface of the bulbs and the pulping bar may be adjusted to allow of any clearance that may be required, according to the variety of coffee to be treated.

Disk pulpers vary in capacity from 1,200 pounds to 14,000 pounds of ripe cherry coffee per hour. They, too, are made in combinations employing cylindrical separators, shaking sieves, and repassing pulpers, for completing the pulping of all unpulped or partially pulped cherries.

Fermentation and Washing

The next step in the process consists in running the pulped cherries into cisterns, or fermentation tanks, filled with water, for the purpose of removing such pulp as was not removed in the pulping machine. The saccharine matter is loosened by fermentation in from twenty-four to thirty-two hours. The mass is kept stirred up for a short time; and, in general practise, the water is drawn off from above, the light pulp floating at the top being removed at the same time. The same tanks are often used for washing, but a better practise is to have separate tanks.

Some planters permit the pulped coffee to ferment in water. This is called the wet fermentation process. Others drain off the water from the tanks and conduct the fermenting operation in a semi-dry state, called the dry fermentation process.

The coffee bean, when introduced into the fermentation tanks, is enclosed in a parchment shell made slimy by its closely adhering saccharine coat. After fermentation, which not only loosens the remaining pulp but also softens the membranous covering, the beans are given a final washing, either in washing tanks or by being run through mechanical washers. The type of washing machine generally used consists of a cylindrical tub having a vertical spindle fitted with a number of stirrers, or arms, which, in rotating, stir and lift up the parchment coffee. In another type, the cylinder is horizontal; but the operation is similar.

Drying

The next step in preparation is drying. The coffee, which is still "in the parchment," but is now known as washed coffee, is spread out thinly on a drying ground, as in the dry method. However, if the weather is unsuitable or can not be depended upon to remain fair for the necessary length of time, there are machines which can be used to dry the coffee satisfactorily. On some plantations, the drying is started in the open and finished by machine. The machines dry the coffee in twenty-four hours, while ten days are required by the sun.

The object of the drying machine is to dry the parchment of the coffee so that it may be removed as readily as the skin on a peanut; and this object is achieved in the most approved machines by keeping a hot current of air stirring through the beans. One of the best-liked types, the Guardiola, resembles the cylinder of a coffee-roasting machine. It is made of perforated steel plates in cylinder form, and is carried on a hollow shaft through which the hot air is circulated by a pressure fan. The beans are rotated in the revolving cylinder; and as the hot air strikes the wet coffee, it creates a steam that passes out through the perforations of the cylinder. Within the cylinder are compartments equipped with winged plates, or ribs, that keep the coffee constantly stirred up to facilitate the drying process. Another favorite is the O'Krassa. It is constructed on the principle just described, but differs in detail of construction from the Guardiola, and is able to dry its contents a few hours quicker. Hot air, steam, and electric heat are all employed in the various makes of coffee driers. A temperature from 65° to 85° centigrade is maintained during the drying process.

When thoroughly dry, the parchment can be crumbled between the fingers, and the bean within is too hard to be dented by finger nail or teeth.

Hulling, Peeling, and Polishing