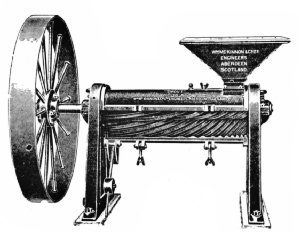

The last step in the preparation process is called hulling or peeling, both words accurately describing the purpose of the operation. Some husking machines for hulling or peeling parchment coffee are polishers as well. This work may be done on the plantation or at the port of shipment just before the coffee is shipped abroad. Sometimes the coffee is exported in parchment, and is cleaned in the country of consumption; but practically all coffee entering the United States arrives without its parchment.

Peeling machines, more accurately named hullers, work on the principle of rubbing the beans between a revolving inner cylinder and an outer covering of woven wire. Machines of this type vary in construction. Some have screw-like inner cylinders, or turbines, others having plain cone-shaped cores on which are knobs and ribs that rub the beans against one another and the outer shell. Practically all types have sieve or exhaust-fan attachments, which draw the loosened parchment and silver skin into one compartment, while the cleaned beans pass into another.

Krull Hulling Machine (German)

Krull Hulling Machine (German)

|

Anderson Hulling Machine (German)

Anderson Hulling Machine (German)

|

Eureka Separator and Grader (American)

Eureka Separator and Grader (American)

|

Caracolillo (Peaberry) Separator (American)

Caracolillo (Peaberry) Separator (American)

|

Engelberg Huller and Separator (American)

Engelberg Huller and Separator (American)

|

The American Coffee Huller and Polisher

The American Coffee Huller and Polisher

|

| WELL KNOWN AMERICAN AND GERMAN HULLING AND SEPARATING MACHINES | |

Polishers of various makes are sometimes used just to remove the silver skin and to give the beans a special polish. Some countries demand a highly polished coffee; and to supply this demand, the beans are sent through another huller having a phosphor-bronze cylinder and cone. Much Guadeloupe coffee is prepared in this way, and is known as café bonifieur from the fact that the polishing machine is called in Guadeloupe the bonifieur (improver). It is also called café de luxe. Coffee that has not received the extra polish is described as habitant; while coffee in the parchment is known as café en parché. Extra polished coffee is much in demand in the London, Hamburg, and other European markets. A favorite machine for producing this kind of coffee is the Smout combined peeler and polisher, the invention of Jules Smout, a Swiss. Don Roberto O'Krassa also has produced a highly satisfactory combined peeler and polisher.

For hulling dry cherry coffee there are several excellent makes of machines. In one style, the hulling takes place between a rotating disk and the casing of the machine. In another, it takes place between a rotary drum covered with a steel plate punched with vertical bulbs, and a chilled iron hulling-plate with pyramidal teeth cast on the plate. Both are adjustable to different varieties of coffee. In still another type of machine, the hulling takes place between steel ribs on an internal cylinder, and an adjustable knife, or hulling blade, in front of the machine.

Sizing or Grading

The coffee bean is now clean, the processes described in the foregoing having removed the outer skin, the saccharine pulp, the parchment, and the silver skin. This is the end of the cleaning operations; but there are two more steps to be taken before the coffee is ready for the trade of the world—sizing and hand-sorting. These two operations are of great importance; since on them depends, to a large extent, the price the coffee will bring in the market.

Old rope-drive transmission on Finca Ona.

Old rope-drive transmission on Finca Ona.

|

Hydro-electric power plant on Finca Ona.

Hydro-electric power plant on Finca Ona.

|

| Hydro-Electric Installation on a Guatemala Finca | |

Sizing, or grading by sizes, is done in modern commercial practise by machines that automatically separate and distribute the different beans according to size and form. In principle, the beans are carried across a series of sieves, each with perforations varying in size from the others; the beans passing through the holes of corresponding sizes. The majority of the machines are constructed to separate the beans into five or more grades, the principal grades being triage, third flats, second flats, first flats, and first and second peaberries. Some are designed to handle "elephant" and "mother" sizes. The grades have local nomenclature in the various countries.

After grading, the coffee is picked over by hand to remove the faulty and discolored beans that it is almost impossible to remove thoroughly by machine. The higher grades of coffee are often double-picked; that is, picked over twice. When this is done on a large scale, the beans are generally placed on a belt, or platform, that moves at a regulated speed before a line of women and children, who pick out the undesirable beans as they pass on the moving belt. There are small machines of this type built for one person, who operates the belt mechanism by means of a treadle.

Preparation in the Leading Countries

The foregoing description tells in general terms the story of the most approved methods of harvesting, shelling, and cleaning the coffee beans. The following paragraphs will describe those features of the processes that are peculiar to the more important large producing countries and that differ in details or in essentials from the methods just outlined.

In the Western Hemisphere

Brazil. The operation of some of the large plantations in Brazil, a number of which have more than a million trees, requires a large number and a great variety of preparation machines and equipment. Generally considered, the State of São Paulo is better equipped with approved machinery than any other commercial district in the world.

In Brazil, coffee plantations are known as fazendas, and the proprietors as fazendeiros, terms that are the equivalent of "landed estates" and "landed proprietors." Practically every fazenda in Brazil of any considerable commercial importance is equipped with the most modern of coffee-cleaning equipment. Some of the larger ones in the state of São Paulo, like the Dumont and the Schmidt estates, are provided with private railways connecting the fazendas with the main railroad line some miles away, and also have miniature railway systems running through the fazendas to move the coffee from one harvesting and cleaning operation to another. The coffee is carried in small cars that are either pushed by a laborer or are drawn by horse or mule.

Manager's Residence on One of the Big São Paulo Fazendas

Manager's Residence on One of the Big São Paulo Fazendas

Drying Grounds on a Modern Estate in Ribeirao Preto

Drying Grounds on a Modern Estate in Ribeirao PretoPhotographs by Courtesy of J. Aron & Co.

MAKING BRAZIL COFFEE READY TO MARKET

Some of the larger fazendas cover thousands of acres, and have several millions of trees, giving the impression of an unending forest stretching far away into the horizon. Here and there are openings in which buildings appear, the largest group of structures usually consisting of those making up the cafezale, or cleaning plant. Nearby, stand the handsome "palaces" of the fazendeiros; but not so close that the coffee princes and their households will be disturbed by the almost constant rumble of machinery and the voices of the workers.

Brazilian fazendeiros follow the methods described in the foregoing in preparing their coffee for market, using the most modern of the equipment detailed under the story of the wet method of preparation. On most of the fazendas the machinery is operated by steam or electricity, the latter coming more and more into use each year in all parts of the coffee-growing region.

In some districts, however, far in the interior, there are still to be found small plantations where primitive methods of cleaning are even now practised. Producing but a small quantity of coffee, possibly for only local use, the cherries may be freed of their parchment by macerating the husks by hand labor in a large mortar. On still another plantation, the old-time bucket-and-beam crusher perhaps may be in use.

This consists of a beam pivoted on an upright upon which it moves freely up and down. On one end of the beam is an open bucket; and on the other, a heavy stone. Water runs into the bucket until its weight causes the stone end of the beam to rise. When the bucket reaches the ground, the water is emptied, and the stone crashes down on the coffee cherries lying in a large mortar.

The workers on some of the largest Brazilian fazendas would constitute the population of a small city—more than a thousand families often finding continuous employment in cultivating, harvesting, cleaning, and transporting the coffee to market. For the most part, the workers are of Italian extraction, who have almost altogether superseded the Indian and Negro laborers of the early days. The workers live on the fazendas in quarters provided by the fazendeiros, and are paid a weekly or monthly wage for their services; or they may enter upon a year's contract to cultivate the trees, receiving extra pay for picking and other work. Brazil in the past has experimented with the slave system, with government colonization, with co-operative planting, with the harvesting system, and with the share system. And some features of all these plans—except slavery, which was abolished in 1888—are still employed in various parts of the country, although the wage system predominates.

Brazil has six gradings for its São Paulo coffees, which are also classified as Bourbon Santos, Flat Bean Santos, and Mocha-seed Santos. Rio coffees are graded by the number of imperfections for New York, and as washed and unwashed for Havre. (See chapter XXIV.)

Colombia. Practically all the countries of the western hemisphere producing coffee in large quantities for export trade use the cleaning-and-grading machines specified in the first part of this chapter; and the installation of the equipment is increasing as its advantages become better known.

In Colombia, now (1922), next to Brazil the world's largest producer, the wet method of preparing the coffee for market is most generally followed, the drying processes often being a combination of sun and drying machines. Many plantations have their own hulling equipment; but much of the crop goes in the cherry to local commercial centers where there are establishments that make a specialty of cleaning and grading the coffee.

The Colombia coffee crop is gathered twice a year, the principal one in March and April and the smaller one in November and December, although some picking is done throughout the year. For this labor native Indian and negro women are preferred, as they are more rapid, skilful, and careful in handling the trees. Contrary to the method in Brazil, where the tree at one handling is stripped of its entire bearings, ripe and unripe fruit, here only the fully ripened fruit is picked. That necessitates going over the ground several times, as the berries progressively ripen. More time is consumed in this laborious operation, but it is believed that thereby a better crop of more uniform grade is obtained and in the aggregate with less waste of time and effort.

Colombian planters classify their coffees as café trillado (natural or sun-dried), café lavado (washed), café en pergamino (washed and dried in the parchment). They grade them as excelso (excellent), fantasia (excelso and extra), extra (extra), primera, (first), segundo (second), caracol (peaberry), monstruo (large and deformed), consumo (defective), and casilla (siftings).

Venezuela. Venezuela employs both the dry and the wet methods of preparation, producing both "washed" and "commons" and also, like Colombia, has a large part of the coffee cleaned in the trading centers of the various coffee districts. Dry, or unwashed, coffees are known as trillado (milled), and compose the bulk of the country's output. Venezuela's plantation-working forces are largely natives of Indian descent and negroes, some of them coming during harvesting season from adjoining Colombia and returning there after the picking is done. The resident workers labor under a sort of peonage system which is tacitly recognized by both employee and employer, although no laws of peonage or slavery have ever existed in Venezuela. Under this system, the laborers live in little colonies scattered over the haciendas, as the coffee plantations are called in Venezuela. Company stores keep them supplied with all their wants. Modern plantation machinery is very scarce; the ancient method of hulling coffee in a circular trough where the dried berries are crushed by heavy wooden wheels drawn by oxen, is still a common sight in Venezuela. In preparing washed coffees, some planters ferment the pulped coffee under water (wet fermentation process); while others ferment without water (dry fermentation).

The principal ports of shipments for Venezuela coffees are La Guaira, Puerto Cabello, and Maracaibo. Caracas, the capital, is five miles in an air line from the port of La Guaira; but in ascending the three thousand feet of altitude to the city the railroad twists and turns among the mountains for a distance of twenty-four miles. By rail or motor the trip is one of much charm and great beauty.

Salvador. The planters in Salvador favor the dry method of coffee preparation; and the bulk of the crop is natural, or unwashed.

Guatemala. Most Guatemalas are prepared for market by the wet method. The gathering of the crops furnishes employment for half the population. German and American settlers have introduced the latest improvements in modern plantation machinery into Guatemala.

Mexico. In Mexico coffee is harvested from November to January, and large quantities are prepared by both the dry and the wet methods, the latter being practised on the larger estates that have the necessary water supply and can afford the machinery. Here, too, one will find coffee being cleaned by the primitive hand-mortar and wind-winnowing method. Laborers are mostly half-breeds and Indians. Chinese coolies have been tried and found satisfactory, and some Japanese are utilized, though not largely.

Haiti. In Haiti the picking season is from November to March. In recent years better attention has been paid to cultural and preparation methods; and the product is more favorably regarded commercially. Large quantities are shipped to France and Belgium; and much of that sent to the United States is reshipped to France, Belgium, and Germany, where it is sorted by hand. Both dry and wet methods are employed in Haiti.

Porto Rico. Here planters favor the wet method of coffee preparation. The crop is gathered from August to December. The coffees are graded as caracollilo (peaberry), primero (hand-picked), segundo (second grade), trillo (low grade).

Nicaragua. The wet method of coffee preparation is mostly favored in Nicaragua. Many of the large plantations are worked by colonies of Americans and Germans who are competent to apply the abundant natural water power of the country to the operation of modern coffee cleaning machinery.

Costa Rica. Costa Rica was one of the first countries of the western world to use coffee cleaning machinery. Marcus Mason, an American mechanical engineer then managing an iron foundry in Costa Rica, invented three machines that would respectively peel off the husk, remove the parchment and pulp, and winnow the light refuse from the beans.

The inventor gave his original demonstration to the planters of San José in 1860, and duplicates were installed on all the large plantations. In the course of the next thirty years, Mason brought out other machines until he had developed a complete line that was largely used on coffee plantations in all parts of the world.

In the Eastern Hemisphere

Modern cleaning machinery and methods of preparation are employed to some extent in the large coffee-producing countries of the eastern hemisphere, and do not differ materially from those of the western.

Arabia. In Arabia the fruit ripens in August or September, and picking continues from then until the last fruits ripen late in the March following. The cherries, as they are picked, are left to dry in the sun on the house-top terrace or on a floor of beaten earth. When they have become partly dry, they are hulled between two small stones, one of which is stationary, while the other is worked by the hand power of two men who rotate it quickly. Further drying of the hulled berry follows. It is then put into bags of closely woven aloe fiber, lined with matting made of palm leaves. It is next sent to the local market at the foot of the mountain. There, on regular market days, the Turkish or Arabian merchants, or their representatives, buy and dispatch their purchases by camel train to Hodeida or Aden. The principal primary market in recent years has been the city of Beit-el-Fakih.

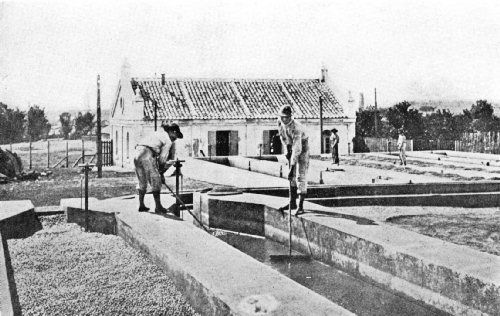

Coffee Drying Patios, Hacienda Longa-Espana, Venezuela

SUN-DRYING COFFEE AMID SCENES OF RARE TROPICAL BEAUTY

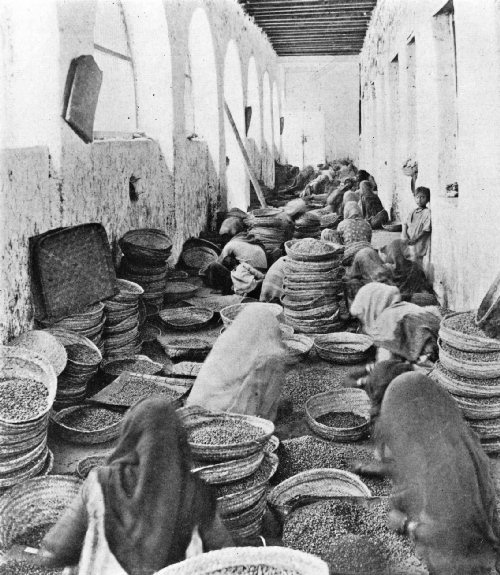

In Aden and Hodeida the bean is submitted to further cleaning by the principal foreign export houses to whom it has come from the mountains in rather dirty condition. Indian women are the sole laborers employed in these cleaning houses. First, the coffee beans are separated from the dry empty husks by tossing the whole into the air from bamboo trays, the workers deftly permitting the husks to fly off while the beans are caught again in the tray. The beans are then surface-cleaned by passing them gently between two very primitive grindstones worked by men. A third process is the complete clearing of the bean from the silver skin, and it is then ready for the final hand picking. Women are called into service again, and they pick out the refuse husks, quaker or black, beans, green or immature beans, white beans, and broken beans, leaving the good beans to be weighed and packed for shipment. The cleaned beans are known as bun safi; the husks become kisher. Some of the poorer beans also are sold, principally to France and to Egypt. Hand-power machinery is used to a slight extent; but mostly the old-fashioned methods hold sway.

The Yemen, or Arabian, bale, or package, is unique. It is made up of two fiber wrappers, one inside the other. The inside one is called attal or darouf. It is made from cut and plaited leaves of nakhel douin or narghil, a species of palm. The outer covering, called garair, is a sack made of woven aloe fiber. The Bedouins weave these covers and bring them to the export merchants at Aden and Hodeida. A Mocha bundle contains one, two, or four fiber packages, or bales. When the bundle contains one bale it is known as a half; when it contains two it is known as quarters; and when it contains four it is known as eighths. Arabian coffee for Boston used to be packed in quarters only; for San Francisco and New York, in quarters and eighths. The longberry Abyssinian coffees were formerly packed in quarters only. Since the World War, however, there has been a scarcity of packing materials, and packing in quarters and eighths has stopped. Now, all Mocha, as well as Harar, coffee comes in halfs. A half weighs eighty kilos, or 176 pounds, net—although a few exporters ship "halfs" of 160 pounds.

INDIAN WOMEN CLEANING MOCHA COFFEE IN AN ADEN WAREHOUSE

There are four processes in cleaning Mocha coffee. In order to separate the dried beans from the broken hulls these women (brought over from India) toss the beans in the air, very deftly permitting the empty hulls to fly off, and catch the coffee beans on the bamboo trays. Then the coffee is passed between two primitive grindstones, turned by men. After this grinding process the beans are separated from the crushed outside hulls and the loose silver skins. In the fourth process the Indian women pick out by hand the remaining husks, the quakers, the immature beans, the white beans and the broken beans. Being Mohammedans, their religion does not permit such little vanities as picture posing, which explains why their faces are covered and turned away from the camera.

Abyssinia. Little machinery is used in the preparation of coffee in Abyssinia; none, in preparing the coffee known as Abyssinian, which is the product of wild trees; and only in a few instances in cleaning the Harari coffee, the fruit of cultivated trees. Both classes are raised mostly by natives, who adhere to the old-time dry method of cleaning. In Harar, the coffee is sometimes hulled in a wooden mortar; but for the most part it is sent to the brokers in parchment, and cleaned by primitive hand methods after its arrival in the trading centers.

Angola. In Angola the coffee harvest begins in June, and it is often necessary for the government to lend native soldiers to the planters to aid in harvesting, as the labor supply is insufficient. After picking, the beans are dried in the sun from fourteen to forty days, depending upon the weather. After drying, they are brought to the hulling and winnowing machines. There are now about twenty-four of these machines in the Cazengo and Golungo districts, all manufactured in the United States and giving satisfactory results. They are operated by natives.

A condition adversely affecting the trade has been the low price that Angola coffee commands in European markets. The cost of production per arroba (thirty-three pounds) on the Cazengo plantations is $1.23, while Lisbon market quotations average $1.50, leaving only twenty-seven cents for railway transport to Loanda and ocean freight to Lisbon. It has been unprofitable to ship to other markets on account of the preferential export duties. A part of the product is now shipped to Hamburg, where it is known as the Cazengo brand. Next to Mocha, the Cazengo coffee is the smallest bean that is to be found in the European markets.

Java and Sumatra. The coffee industry in Java and Sumatra, as well as in the other coffee-producing regions of the Dutch East Indies, was begun and fostered under the paternal care of the Dutch government; and for that reason, machine-cleaning has always been a noteworthy factor in the marketing of these coffees. Since the government relinquished its control over the so-called government estates, European operators have maintained the standard of preparation, and have adopted new equipment as it was developed. The majority of estates producing considerable quantities of coffee use the same types of machinery as their competitors in Brazil and other western countries.

In Java, free labor is generally employed; while on the east coast of Sumatra the work is done by contract, the workers usually being bound for three years. In both islands the laborers are mostly Javanese coolies.

Under the contract system, the worker is subject to laws that compel him to work, and prevent him from leaving the estate until the contract period expires. Under the free-labor system, the laborer works as his whims dictate. This forces the estate manager to cater to his workers, and to build up an organization that will hold together.

As an example of the working of the latter system, this outline—by John A. Fowler, United States trade commissioner—of the organization of a leading estate in Java will indicate the general practise in vogue:

The manager of this estate has had full control for twenty years and knows the "adat" (tribal customs) of his people and the individual peculiarities of the leaders. This estate has been described as having one of the most perfect estate organizations in Java. It consists of two divisions of 3,449 bouws (about 6,048 acres in all), of which 2,500 bouws are in rubber and coffee and 550 in sisal; the remainder includes rice fields, timber, nurseries, bamboo, teak, pastures, villages, roads, canals, etc.

The foreign staff is under the supervision of a general manager, and consists of the following personnel: A chief garden assistant of section 1, who has under him four section assistants and a native staff; a chief garden assistant of section 2, who has under him three section assistants, an apprentice assistant, and a native staff; a chief factory assistant, who has under him an assistant machinist, an apprentice assistant, and a native staff; and, finally, a bookkeeper. The term "garden" means the area under cultivation.

The bookkeeper, a man of mixed blood, handles all the general accounting, accumulating the reports sent in by the various assistants. The two chief garden assistants are responsible to the manager for all work outside the factory except the construction of new buildings, which is in charge of the chief factory assistant. The two divisions of the estate are subdivided into seven agricultural sections, each section being in full charge of an assistant. A section may include coffee, rubber, sisal, teak, bamboo, a coagulation station and nurseries. The assistant's duties include the supervision of road building and repairs, building repairs, transportation, paying the labor, and the supervision of section accounts.

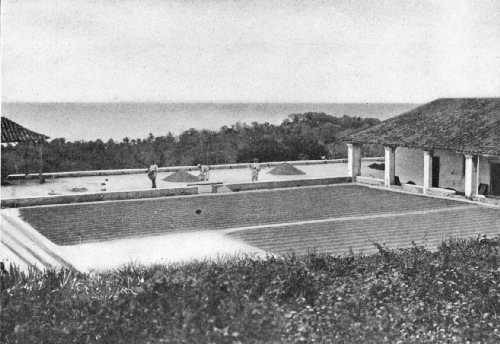

Open-air Drying Grounds on a West Java Estate

Open-air Drying Grounds on a West Java EstateThe beans are being turned by native Sudanese men and women

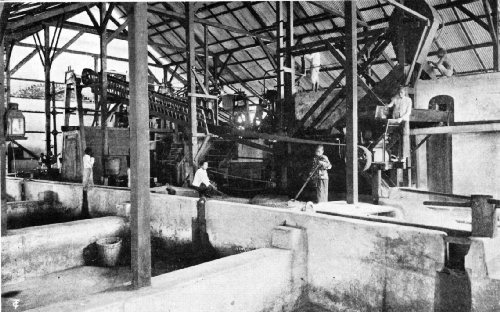

Interior of a Modern Coffee Factory in East Java

Interior of a Modern Coffee Factory in East JavaShowing pulping machinery and fermentation tanks

PREPARING JAVA COFFEE FOR THE MARKET

The factory includes a water-power plant delivering, through an American water wheel and by cable, 250 horse-power to the main shafting, an auxiliary steam plant of 150 horse-power as a reserve, a rubber mill, a coffee mill, three sisal-stripping machines, smoke-houses, drying fields and houses for sisal, drying floors and houses for coffee, sorting rooms, blacksmith shop, machine shop, brass-fitting foundry, packing houses, warehouses, and other equipment. The factory is in charge of a first assistant, who is a machinist, with a European staff consisting of a machinist and an apprentice assistant.

The chief garden assistant is paid 350 to 400 florins, and the garden assistants start at 200 florins per month, with graduated yearly increases up to 300 florins per month (florin=$0.40). The chief factory assistant receives 300 florins, and the machinist and bookkeeper 250 florins each.

The mandoer in charge of the air and kiln drying of coffee gets 25 florins per month, and the mandoer at the coffee mill 20 florins. A woman mandoer in charge of the coffee sorters receives 0.50 florin per day and 0.01 florin each for sewing the bags. This woman supervises all the sorters, fixes their status, and inspects their work. Unskilled labor (male) receives 0.40 florin per day in the coffee sheds, and the women sorters are paid 0.50 florin per picul of 136 pounds, measured before sorting. These women are graded into three classes—those who can sort 1 picul in a day, those who can sort three-fourths of a picul, and those who can sort but one-half of a picul in a day. Some of these women become very expert in sorting, and the quality of the output of a factory is largely dependent on an ample supply of expert sorters. Many years are required to develop an adequate personnel for this department.

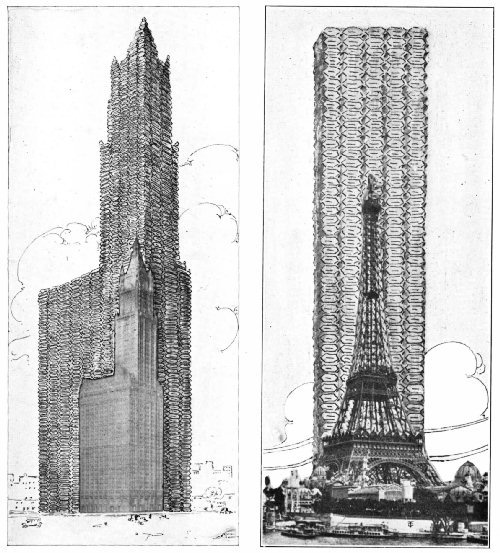

THE WORLD'S COFFEE TOWER COMPARED WITH THE EIFFEL AND WOOLWORTH TOWERS

THE WORLD'S COFFEE TOWER COMPARED WITH THE EIFFEL AND WOOLWORTH TOWERS

The Woolworth Building, the world's loftiest office structure is 792 feet high from street to top of tower; its main section of 151 by 196 feet stretches up 386 feet, and its volume equals a total of 13,110,942 cubic feet. But a tower made of the year's supply of bags of green coffee (132 pounds each) would equal 73,649,115 cubic feet, or nearly six times the bulk of the Woolworth Building. In the same proportions it would rise 1,386 feet, with the lower section 260 by 340 feet and 670 feet high. Its dimensions would be nearly double those of the Woolworth Building in every direction. And the Eiffel Tower, reaching up 1,000 feet toward the sky would be lost in a tower made of a year's bags of coffee. Such a tower would stand 1,425 feet high on a base area of 230 feet square, the size of the Eiffel's first floor.

CHAPTER XXII

THE PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION OF COFFEE

A statistical study of world production of coffee by countries—Per capita figures of the leading consuming countries—Coffee-consumption figures compared with tea-consumption figures in the United States and the United Kingdom—Three centuries of coffee trading—Coffee drinking in the United States, past and present—Reviewing the 1921 trade in the United States

The world's yearly production of coffee is on the average considerably more than one million tons. If this were all made up into the refreshing drink we get at our breakfast tables, there would be enough to supply every inhabitant of the earth with some sixty cups a year, representing a total of more than ninety billion cups. In terms of pounds the annual world output amounts to about two and a quarter billions—an amount so large that if it were done up in the familiar one-pound paper packages; and if these packages were laid end to end in a row; they would form a line long enough to reach to the moon. If this average yearly production were left in the sacks in which the coffee is shipped, the total of 17,500,000 would be enough to form a broad six-foot pavement reaching entirely across the United States, upon which a man could walk steadily for more than five months at the rate of twenty miles a day. This vast amount of coffee comes very largely from the western hemisphere; and about three-fourths of it, from a single country. The production, shipment, and preparation of this coffee, directly and indirectly support millions of workers; and many countries are entirely dependent on it for their prosperity and economic well-being.

During the crop year that ended June 30, 1921, this million-ton average was considerably exceeded, though it did not approach the record yield of all time in the crop year 1906–07, when the total amounted to almost 24,000,000 sacks; or, in round numbers, 3,000,000,000 pounds.

As indicated by the Statistical Record table, on page 274, Brazil produces more than all the rest of the world put together. Coffee growing, however, is general throughout tropical countries, and in most of them constitutes one of the leading industries. Yet in most cases, the actual production of these countries can only be estimated, as accurate figures, showing the exact output, are seldom kept. But the contribution which each country makes to the total world traffic in coffee can be determined by its export figures, which are obtainable in reasonably accurate and up-to-date form. The table on page 276 gives the coffee export figures, in pounds, for practically every country that produces coffee for sale outside its own borders. Figures are given for the latest available year, and also for the average of the last five years for which statistics are to be obtained. The figures are taken from official statistics, from the publications of the International Institute of Agriculture of Rome, and from other authoritative sources.

| Statistical Record for Thirty-eight Years | ||||||||

| Crops | Deliveries | |||||||

| Fiscal Year (July 1 to June 30) |

Rio and Santos (Bags)[I] |

Other Countries (Bags) |

Total (Bags) |

Europe (Bags) |

United States (Bags) |

Total (Bags) |

Visible Supply July 1. (Bags) |

Quotations, Rio No. 7 New York, July 1. |

| 1883–84 | 5,047,000 | 4,526,000 | 9,573,000 | 6,774,000 | 2,635,000 | 9,409,000 | ||

| 1884–85 | 6,206,000 | 4,004,000 | 10,210,000 | 7,388,000 | 3,169,000 | 10,557,000 | 5,398,000 | 81⁄4 |

| 1885–86 | 5,565,000 | 3,505,000 | 9,070,000 | 7,198,000 | 2,938,000 | 10,136,000 | 5,051,000 | 71⁄8 |

| 1886–87 | 6,078,000 | 4,106,000 | 10,184,000 | 7,363,000 | 2,672,000 | 10,035,000 | 3,985,000 | 81⁄4 |

| 1887–88 | 3,033,000 | 3,214,000 | 6,247,000 | 5,888,000 | 2,164,000 | 8,052,000 | 4,134,000 | 167⁄8 |

| 1888–89 | 6,827,000 | 3,672,000 | 10,499,000 | 6,589,000 | 2,659,000 | 9,249,000 | 2,329,000 | 131⁄2 |

| 1889–90 | 4,260,000 | 3,965,000 | 8,225,000 | 6,716,000 | 2,704,000 | 9,420,000 | 3,579,000 | 141⁄2 |

| 1890–91 | 5,358,000 | 2,886,000 | 8,244,000 | 6,046,000 | 2,673,000 | 8,719,000 | 2,384,000 | 171⁄2 |

| 1891–92 | 7,397,000 | 4,453,000 | 11,850,000 | 6,392,000 | 4,412,000 | 10,804,000 | 1,909,000 | 173⁄8 |

| 1892–93 | 6,203,000 | 4,887,000 | 11,090,000 | 6,457,000 | 4,389,000 | 10,945,000 | 2,955,000 | 177⁄8 |

| 1893–94 | 4,309,000 | 5,307,000 | 9,616,000 | 6,272,000 | 4,298,000 | 10,570,000 | 3,100,000 | 165⁄8 |

| 1894–95 | 6,695,000 | 5,069,000 | 11,764,000 | 6,816,000 | 4,396,000 | 11,212,000 | 2,146,000 | 161⁄2 |

| 1895–96 | 5,476,000 | 4,901,000 | 10,377,000 | 6,803,000 | 4,339,000 | 11,142,000 | 3,115,000 | 153⁄4 |

| 1896–97 | 8,680,000 | 5,238,000 | 13,918,000 | 7,155,000 | 5,080,000 | 12,244,000 | 2,588,000 | 13 |

| 1897–98 | 10,462,000 | 5,596,000 | 16,058,000 | 8,535,000 | 6,036,000 | 14,571,000 | 3,975,000 | 73⁄8 |

| 1898–99 | 8,771,000 | 4,985,000 | 13,756,000 | 7,798,000 | 5,682,000 | 13,480,000 | 5,435,000 | 61⁄4 |

| 1899–00 | 8,959,000 | 4,842,000 | 13,801,000 | 8,937,000 | 6,035,000 | 14,972,000 | 6,200,000 | 61⁄8 |

| 1900–01 | 10,927,000 | 4,173,000 | 15,100,000 | 8,486,000 | 5,843,000 | 14,329,000 | 5,840,000 | 815⁄16 |

| 1901–02 | 15,439,000 | 4,296,000 | 19,735,000 | 8,853,000 | 6,663,000 | 15,516,000 | 6,867,000 | 6 |

| 1902–03 | 12,324,000 | 4,340,000 | 16,664,000 | 9,118,000 | 6,847,000 | 15,966,000 | 11,261,000 | 51⁄4 |

| 1903–04 | 10,408,000 | 5,575,000 | 15,983,000 | 9,280,000 | 6,853,000 | 16,133,000 | 11,900,000 | 53⁄16 |

| 1904–05 | 9,968,000 | 4,480,000 | 14,448,000 | 9,475,000 | 6,687,000 | 16,163,000 | 12,361,000 | 71⁄8 |

| 1905–06 | 10,227,000 | 4,565,000 | 14,792,000 | 9,934,000 | 6,806,000 | 16,741,000 | 11,265,000 | 73⁄4 |

| 1906–07 | 19,654,000 | 4,160,000 | 23,814,000 | 10,502,000 | 7,042,000 | 17,544,000 | 9,636,000 | 715⁄16 |

| 1907–08 | 10,283,000 | 4,551,000 | 14,834,000 | 10,481,000 | 7,043,000 | 17,525,000 | 16,400,000 | 63⁄8 |

| 1908–09 | 12,419,000 | 4,499,000 | 16,918,000 | 11,129,000 | 7,519,000 | 18,649,000 | 14,126,000 | 61⁄4 |

| 1909–10 | 14,944,000 | 4,181,000 | 19,125,000 | 10,811,000 | 7,287,000 | 18,098,000 | 12,841,000 | 73⁄4 |

| 1910–11 | 10,548,000 | 3,976,000 | 14,524,000 | 10,492,000 | 7,015,000 | 17,507,000 | 13,719,000 | 83⁄8 |

| 1911–12 | 12,491,000 | 4,918,000 | 17,409,000 | 10,712,000 | 6,762,000 | 17,474,000 | 11,070,000 | 131⁄8 |

| 1912–13 | 11,458,000 | 4,915,000 | 16,373,000 | 10,144,000 | 6,675,000 | 16,820,000 | 11,048,000 | 143⁄4 |

| 1913–14 | 13,816,000 | 5,796,000 | 19,612,000 | 11,027,000 | 7,545,000 | 18,573,000 | 10,285,000 | 95⁄8 |

| 1914–15 | 12,867,000 | 5,019,000 | 17,886,000 | 13,368,000 | 8,010,000 | 21,378,000 | 11,302,000 | 83⁄4 |

| 1915–16 | 14,992,000 | 4,764,000 | 19,756,000 | 11,050,000 | 8,834,000 | 19,884,000 | 7,523,000 | 71⁄2 |

| 1916–17 | 12,112,000 | 4,579,000 | 16,691,000 | 5,171,000 | 9,046,000 | 14,217,000 | 7,328,000 | 91⁄8 |

| 1917–18 | 15,127,000 | 3,720,000 | 18,847,000 | 6,209,000 | 8,624,000 | 14,833,000 | 7,793,000 | 91⁄2 |

| 1918–19 | 9,140,000 | 4,500,000 | 13,640,000 | 6,073,000 | 8,994,000 | 15,067,000 | 8,783,000 | 81⁄2 |

| 1919–20 | 6,700,000 | 8,463,000 | 15,163,000 | 7,047,000 | 9,683,000 | 16,730,000 | 7,173,000 | 221⁄4 |

| 1920–21 | 13,816,000 | 6,467,000 | 20,283,000 | 6,397,000 | 9,701,000 | 16,099,000 | 6,909,000 | 131⁄4 |