Chapter XXV

FACTORY PREPARATION OF ROASTED COFFEE

Coffee roasting as a business—Wholesale coffee-roasting machinery—Separating, milling, and mixing or blending green coffee, and roasting by coal, coke, gas, and electricity—Facts about coffee roasting—Cost of roasting—Green-coffee shrinkage table—"Dry" and "wet" roasts—On roasting coffee efficiently—A typical coal roaster—Cooling and stoning—Finishing or glazing—Blending roasted coffees—Blends for restaurants—Grinding and packaging—Coffee additions and fillers—Treated coffees, and dry extracts

The coffee bean is not ready for beverage purposes until it has been properly "manufactured", that is, roasted, or "cooked". Only in this way can all the stimulating, flavoring, and aromatic principles concealed in the minute cells of the bean be extracted at one time. An infusion from green coffee has a decidedly unpleasant taste and hardly any color. Likewise, an underdone roast has a disagreeable "grassy" flavor; while an overdone roast gives a charred taste that is unpalatable to the average citizen of the United States.

Coffee Roasting as a Business

In spite of the generally admitted fact that freshly roasted coffee makes the best infusion, most of the coffee used today is not roasted at or near the place where it is brewed, but in factories that are provided with special equipment for the roasting of coffee in a wholesale way. The reasons for this are various, partly relating to the mere economy of buying and manufacturing on a large scale, and partly relating to the trained skill that is needed both for selecting suitable green coffees to make a satisfactory blend, and for the roasting work itself. The proportion of consumers (including restaurants and hotels) who roast their own coffee is so small as to be negligible, at least in the United States. The average person who buys coffee today, for brewing use, never sees green coffee at all, unless as an "educational exhibit" in some dealer's display window.

The reasons just mentioned, which have made coffee roasting a real business, all tend, of course, to make the roasting establishments of large size; but this tendency is offset by the problem of distributing the roasting coffee so that it will reach the ultimate consumer in good condition. Roasting enterprises on a comparatively small scale (not by consumers, but by sufficiently expert dealers) would probably be much more numerous on account of the "fresh-roast" argument, except for the fact that coffee-roasting machines can not be installed so easily as the grinding mills, meat-choppers, and slicing machines, that find extended use in small stores. The steam, smoke, and chaff given off by the coffee as it is roasted must be disposed of by an outdoor connection, without annoying the neighbors or creating a fire hazard.

From these general remarks, it can easily be seen that the size of individual roasting establishments will vary greatly, according to the skill of the proprietor in meeting the disadvantages of working on either the smallest or the largest scale. A wholesale plant may be considered to be one in which coffee is roasted in batches of one bag or more at a time; and with this definition, nearly all the roasting in the United States is done in a wholesale way.

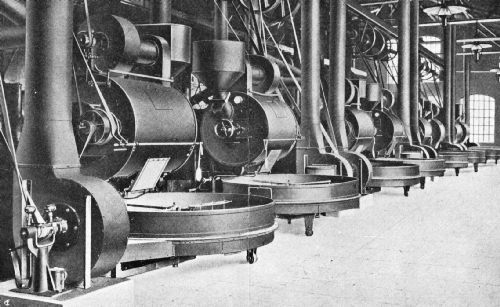

A MODERN GAS COFFEE-ROASTING PLANT WITH A CAPACITY OF 1,000 BAGS A DAY

A MODERN GAS COFFEE-ROASTING PLANT WITH A CAPACITY OF 1,000 BAGS A DAY

General view of the roasting room of the Jewel Tea Co., Hoboken, N.J. The equipment consists of twelve Jubilee gas machines in four groups; each group having a smoke-suction fan, and a drag conveyor over the three feed hoppers. To the left is a line of flexible-arm cooler cars.

For many years the regular factory machines have been of a size suitable for roasting two bags of coffee at a time; but roasters of larger size have recently come into considerable use.

Plants treating from fifty to a hundred and fifty bags per day are the most common; but the daily capacity runs up to a thousand bags or more. The minimum cost of equipping a plant is somewhere between five thousand dollars and ten thousand dollars. The individual machines are of standard construction; but the arrangement in a particular building, especially for the larger plants, is worked out with great care and with numerous special features, so that the goods can be handled from start to finish with minimum expense for floor space, labor, power, etc.

The practical coffee roaster locates his roasting room in the top floor of his factory building, where light and ventilation are generally best. He usually has a large skylight in the roof, directly over the roasting equipment. In addition to the advantage as regards good light and the convenient discharge of smoke, steam, and odors, through the roof, the top-story location makes it possible to send the roasted coffee by gravity through the various bins which may be needed in connection with subsequent operations, such as grinding, and for temporary storage before the final packaging and shipping.

Wholesale Coffee-Roasting Machinery

The indispensable coffee operations are roasting and cooling; and in practically all United States plants the cooling is followed by "stoning". This is an air-suction operation that effects, aided by gravity, the removal of any stones or other hard material that would damage the grinding mill. The best commercial cleaning and grading of the green coffee has usually left in every bag a few small stones. These can be got rid of better after the coffee is roasted; because it is then not only lighter, but more bulky.

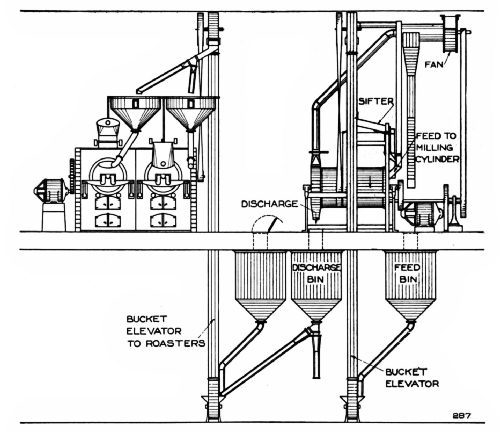

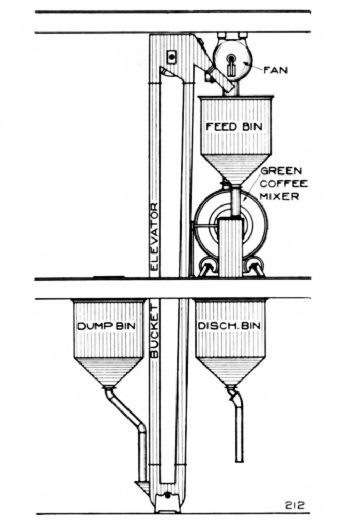

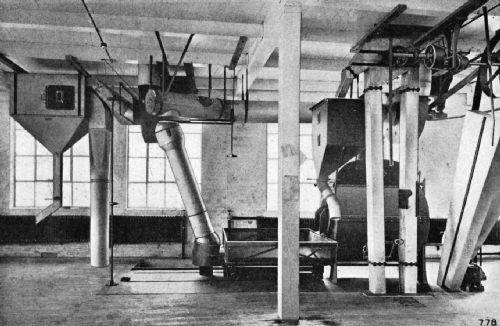

Milling-Machine Connections for a Two-Roaster Plant

Milling-Machine Connections for a Two-Roaster PlantBesides these three operations of roasting, cooling, and stoning, the plant may have machinery for treating the coffee both before it is roasted and after it leaves the stoner.

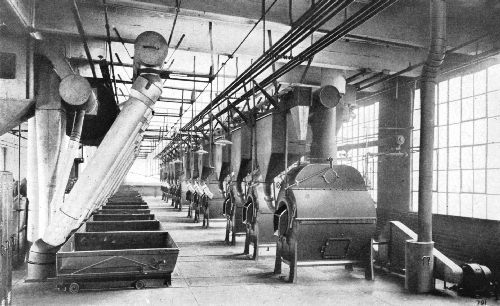

A SIXTEEN-CYLINDER COAL ROASTING PLANT IN A NEW YORK FACTORY

This is a view of the roasting room of B. Fischer & Co. and shows a battery of Burns coal roasters

Treatment of the green coffee in roasting establishments is of less importance now than in years gone by; first, because most coffees now come to market more perfectly graded and cleaned than formerly; and second, because the whole-bean appearance of the coffee has become of less account, as wholesale grinding operations have increased. Nevertheless, many plants consider it highly important to have a separator for grading the coffee closely as regards the size of the beans—and particularly for the separation of round beans, or "peaberry"—as well as milling machinery for making the coffee as clean as possible before it is roasted. One green coffee operation that has lost none of its old-time importance, but on the contrary is more needed as the plants increase in size, is the mixing of different varieties of coffee—in proportions that have been decided on by sample tests—so as to get a uniform blend.

The mixer does not blend the various coffees any more surely than a good roaster cylinder will do it, but treats batches of much larger size. This means saving a great amount of labor that would be necessary for putting the desired quantity of component coffees into each individual roaster.

A proper installation of green coffee machinery requires various bins of ample capacity, and bucket elevators by which the coffee can be sent without manual labor from one operation to another. In modern plants, all the bins and elevators are constructed of metal. The separator, with its bins and elevator, may be installed independently of the rest of the plant, the graded coffee being all bagged up again and treated as new raw stock—some of it to be held for later use, or perhaps sold again unroasted. The milling machine and the mixer, however, are usually so placed and connected that the coffee can be sent from one to the other, and to the roaster feed hoppers, without any manual labor.

When the roaster sells his product in package form ready for the consumer, he will have a packaging department in which are grinding, weighing, labeling, and packing machines and equipment. In some of the more progressive plants, particularly in the United States, all the packing units are incorporated in one machine, so that the different steps in the work are carried on automatically and in one continuous operation.

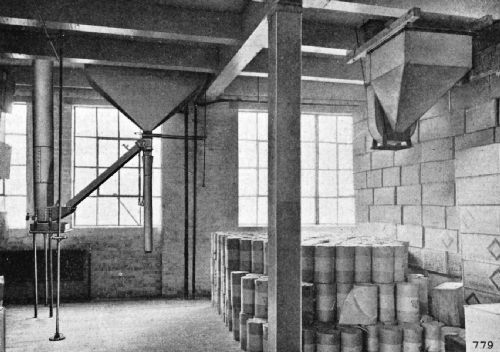

Green-Coffee-Mixer Connections

To operate at full capacity, without using the story above as well as below the mixer, requires a bucket elevator and three bins, each holding a full mixing batch. The above diagram explains this setting. The mixed coffee in the discharge bin is either drawn out into bags or sent by an elevator to a milling machine or direct to the coffee roasters. A batch ready for mixing can always be accumulated in the feed bin while the previous batch is being mixed or discharged.

The fan is usually hung to the ceiling over the mixer as indicated, and connected to the suction box by a 1-in. round pipe. The fan outlet can be carried directly out-of-doors; but the dusty discharge is objectionable in most installations, and this pipe is usually carried to a dust collector from the top of which the roof outlet is connected.

The efficient roaster-executive equips his entire plant with approved labor-saving devices. In the better establishments, the coffee is carried along by mechanical conveyors through all the operations from the first cleaning machine to the final packaging.

Separating

As already mentioned, a machine frequently found in wholesale plants is the separator, or grader. This apparatus, which is the same in principle in all countries, but varies in size and form according to local requirements, consists of a series of perforated screens. The perforations differ in size; and as the coffee is shaken on them, the small beans drop through the holes, the larger ones passing across the screen and dropping into a receptacle or chute ready for the next operation. The screens are made to grade the beans into large and small peaberry; large, medium, and small flat beans; brokens; and other commercial sizes. The average separator will grade fifteen to twenty bags of coffee in an hour.

Green-coffee-milling machine having a capacity of forty bags of green coffee per hour; with sifter, feed-pipe suction, and a final separate suction at the discharge hopper |

Green-coffee separator without fan; with feed elevator, discharge chutes, and motor drive. View of right-hand side and feed end |

| GREEN-COFFEE SEPARATING AND MILLING MACHINES | |

Milling

Milling machines, for cleaning the green coffee, operate on practically the same principle the world over, varying in capacity and details of construction. A popular type used in the United States has two metal cylinders, one set within the other, and revolving in opposite directions. The inner cylinder is ribbed with flanges, and the outer one is lined with wire cloth. As these cylinders revolve, the beans pass between them rubbing against themselves and the rough sides of the cylinders. This action serves to remove dirt and other foreign matter that may be clinging to the beans, and also gives them an attractive polish. An exhaust fan sucks away the dirt milled off in the process. This type of machine will mill about forty bags of green coffee in an hour.

Mixing or Blending Green Coffee

Most roasters blend the different types of coffee while green. Some blend them after they have been roasted separately. When blended before roasting, the coffees are mixed by a machine built especially for that purpose. The mixing machine in general use in all countries consists of a large metal cylinder which, in wholesale operations, is revolved by the factory's general power plant or by a separate motor. The cylinder is equipped on the inside with sets of reverse-screw mixing flanges that tumble the beans around until they are thoroughly blended; and there is usually a fan attachment to remove dust. This operation serves also to smooth down and to polish the surfaces of the beans, which adds to the style of the coffee when roasted. The average blending machine will mix from ten to twenty bags of coffee at a time. The actual mixing requires less than five minutes, but a longer period is needed for feeding and discharging. This is the last of the so-called "green-coffee operations". The next step is roasting.

Roasting by Coal, Coke, Gas, and Electricity

Coffee is roasted commercially in cylinder or ball receptacles revolving in heated chambers, the degree of heat reaching about 420° Fahr. The cylinder type of roaster is invariably used in the United States; while both the cylinder and the ball types are popular in England, France, Germany, Holland, and other foreign countries.

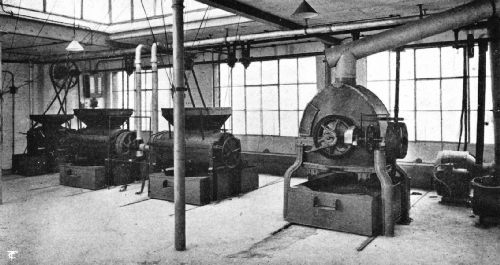

An English Four-Machine Gas Coffee-Roasting Plant

The equipment includes three Morewood indirect-flame, and one quick direct-flame machines

Each roasterman has his own opinion about the fuel that gives the best result, and throughout the world the choice lies between anthracite coal, coke, and gas; though hard wood is frequently used in countries where other fuels are not available or not economical. Electric heat has been tried for commercial roasting in Germany (1906), in England (1909), and in the United States (1918); but the experimenters have always found the cost of electric fuel to be prohibitive in competition with coal and gas. An electric roaster was demonstrated at the Food Conservation Show in New York, in 1918, at a time when the federal government was urging the necessity of conserving coal as a war economy measure. The inventor claimed that his machine would reduce roasting cost, improve the flavor and the aroma, and maintain a constant and easily controlled heat. He declared also that when roasted in his devices, less coffee was required for brewing.

An expert coffee-roasting-machinery man who has been working on the development of a practical electric roaster says that if it were possible to bake the coffee in an oven, just as the baker does his bread, the fuel cost would then compare favorably with that of gas or coal. It is because the heat chamber must have an exhaust to release the chaff and smoke that the use of electricity to replace the heat loss proves prohibitive when compared with coal or gas.

In all types of coal and coke burning roasters, the cylinders are heated by a fire underneath; while in gas roasters, the flame may be underneath or within the cylinder itself. Roasters in which the heat is within the cylinder are known as direct-flame or inner-heated machines. All three systems are used in the United States and Europe.

Facts About Coffee Roasting

The modern commercial roasting outfit is as near fool-proof as human genius has been able to devise. The more advanced types are almost automatic in operation, and are designed to insure uniformity of roasts. In such machines the green coffee is conveyed to the roasting cylinder by means of bucket elevators, which pour the beans into a feed hopper. From the feed hopper, the coffee is dumped through the opening in the front head-piece into the cylinder. The cylinder is perforated, and has inside flanges which keep tossing the coffee about while the cylinder revolves, so that the coffee will not burn during the roasting process.

To roast coffee by coal or coke usually requires from twenty-five to thirty minutes, depending on the moisture-content of the beans; whether they are spongy or flinty; whether a light, medium, or dark roast is desired; and on the skill of the operator. Gas roasting requires from fifteen to twenty minutes. The quicker the roast, the better the coffee, is the opinion of many trade leaders, one of whom[325] says:

It is a growing belief that in roasts of short duration the largest percentage of the aromatic properties is retained. A slow roast has the effect of baking and does not give full development; also, slow roasts seldom produce bright roasts, and they usually make the coffee hard instead of brittle, even when the color standard has been attained.

While coffees of widely varying degrees of moisture require somewhat different treatment, the consensus of opinion is that the best results are obtained from a slow fire at the beginning, until some of the moisture has been driven off, when the stronger application of heat may be given for development. An intense heat in the beginning often results in "tipping", or charring, the little germ at the end, the most sensitive part of the bean.

Scorched beans have been caught at some point in the cylinder, often in a bent flange. Burning on one face, sometimes called "kissing the cheeks", is caused by the too rapid revolution of the cylinder, so that some of the coffee "carries over". In the best practise, crowding of cylinders is avoided; many roasters making it a rule not to exceed ninety percent of the rated capacity of the cylinder.

Those operating gas roasters may effect a fuel economy by running a low grade coffee in the cylinder after the last roast has been drawn and the gas extinguished; five minutes' revolution absorbs the heat and drives off a proportion of moisture. The coffee, which may then be left in the cylinder, requires less time and fuel in the morning, and the roast is finished while the cylinder is warming up. Double roasting brightens a roast, but is a detriment to the cup quality. A dull roasting coffee may be improved by revolving the green coffee in a cylinder without heat for twenty minutes, which has the effect of milling.

The use of a small amount of water upon roasts gives better control by checking the roast at the proper point—the crucial time of its greatest heat; also, it swells and brightens the coffee, and tends to close the outer pores. While the addition of water is open to abuse, few roasters have soaked their coffees enough to offset the natural shrinkage as much as three or four percent. Such practise would result greatly to the detriment of the cup quality.

There is no universal standard for the degree to which coffee should be roasted. In the United States, there are demands for all degrees; from the light roast, in favor in England, to the extremely dark roast in vogue in France, Italy, Brazil, Turkey, and in the producing countries. The North American trade recognizes these different roasts: light, cinnamon, medium, high, city, full city, French, and Italian. The city roast is a dark bean, while full city is a few degrees darker. In the French roast, the bean is cooked until the natural oil appears on the surface; and in the Italian, it is roasted to the point of actual carbonization, so that it can be easily powdered. Germany likes a roast similar to the French type; while Scandinavia prefers the high Italian roast.

In the United States, the lighter roast is favored on the Pacific coast; the darkest, in the South; and a medium-colored roast, in the Eastern states. The cinnamon roast is most favored by the trade in Boston.

While coffee roasting in the United States usually takes from fifteen to thirty minutes, depending on the fuel and the machine employed, manufacturers of gas machines on the German market claim to roast it in superior fashion in from three and a half to ten minutes.[326] This subject is discussed more in detail in chapter XXXIV.

Coffee loses weight during the roasting process, the loss varying according to the degree of roasting and the nature of the bean. Coffee roasters figure, however, that the average loss is sixteen percent of the weight of the green bean. It has been estimated that one hundred pounds of coffee in the cherry produces twenty-five pounds in the parchment; that one hundred pounds in parchment produces eighty-four pounds of cleaned coffee; and that one hundred pounds of cleaned coffee produces eighty-four pounds roasted.

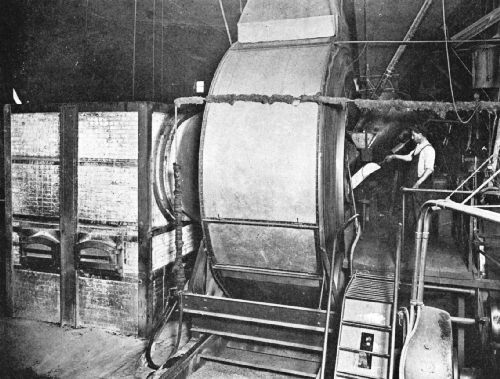

Jumbo Coffee Roaster, in the Arbuckle Coffee-Roasting Plant, New York

Jumbo Coffee Roaster, in the Arbuckle Coffee-Roasting Plant, New YorkThere are four of these machines. The cylinders are twelve feet in diameter, six feet deep, and can roast 5,000 pounds of coffee every half-hour. The hard-coal brick furnace is seen at the left, from which a blower forces the heated air through a pipe into the revolving cylinder of coffee. The coffee is fed from above and is emptied into the cooling pans beneath

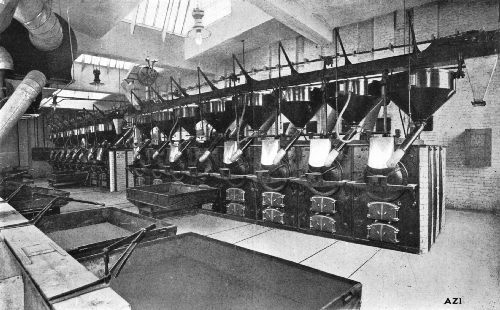

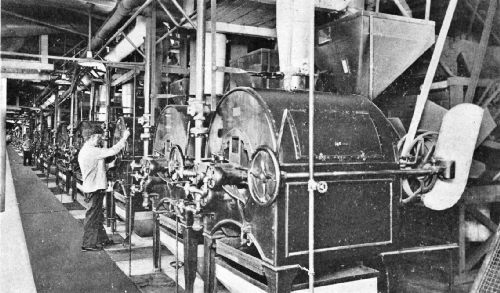

An Eight-Cylinder Gas Coffee-Roasting Plant

An Eight-Cylinder Gas Coffee-Roasting PlantA view of Reid, Murdoch & Co.'s roasting room, Chicago, equipped with Monitor machines

During the roasting process the coffee undergoes a great chemical change. After it has been in the cylinder a short time, the color of the bean becomes a yellowish brown, which gradually deepens as it cooks. Likewise, as the beans become heated, they shrivel up until about half done, or at the "developing" point. At this stage, they begin to swell, and then "pop open", increasing fifty percent in bulk.[327] This is when the experienced roasterman turns on all the heat he can command to finish the roasting as quickly as possible.

"Dry" and "Wet" Roasts

At frequent intervals, he thrusts his "trier"—an instrument shaped somewhat like an elongated spoon—into the cylinder, and takes out a sample of coffee to compare with his type sample. When the coffee is done, he shuts off the heat and checks the cooking by reducing the temperature of the coffee and of the cylinder as quickly as can be done. In the wet roast method he will spray the coffee, while the cylinder is still revolving, with three to four quarts of water to every 130 pounds of coffee. In the dry method he depends altogether upon his cooling apparatus.

Roasters generally are not in favor of the excessive watering of coffee in and after the roasting process for the purpose of reducing shrinkage. "Heading" the coffee, or checking the roast before turning it out of the roasting cylinder, is quite another matter and is considered legitimate. Where coffees are watered in the cylinder at the close of the roast to reduce the shrinkage, it is possible to get back only about four percent of the shrinkage by such treatment and the practise is frowned upon by the best roasters.

Generally speaking, water is turned into the roasting cylinder to quench the roast. The amount varies with the style of machine, whether gas or coal. Usually the water turns to steam, and the result is not an absorption of the water but a momentary checking of the roast with a tendency to swell and to brighten the coffee. This is, comparatively speaking, a "dry roast", but not an absolutely dry roast. It is doubtful if more than one percent of American coffee roasters employ an absolutely "dry" roast—it does not give satisfactory results. The word has been abused for advertising purposes. Of course, a dry roasted coffee is a better article for making a satisfactory beverage than one that has been soaked with water; but the word "dry" must be given a definite meaning, which the trade generally will agree to uphold, if it is to have any real meaning or value to the consumer. Until some standard for roasted coffee shall be established, it is to be feared the term "dry roast" will continue to be used for coffee roasted by almost any other process.

Upper-Story View of a Jubilee Plant, Showing Roaster, Cooler, and Stoner Equipment

The parts under roasting-room floor are shown in the illustration below

Lower-Story View of the Same Plant from About the Same Angle

Lower-Story View of the Same Plant from About the Same AngleShowing connection from floor hopper to stoner on the left, and suspended bucket-elevator boot with four-bag dump hopper on the right

COMPLETE GAS COFFEE-PLANT INSTALLATION

The Bureau of Chemistry held a hearing in 1914 at Washington, at which the question of a ruling on watering coffees was discussed. The trade was well represented, but no agreement was reached. It was deemed inadvisable to make a definite rule on the watering of coffee; because the water content can not be controlled, as the bean starts to absorb moisture as soon as it leaves the roaster.

On Roasting Coffee Efficiently

A.L. Burns, New York, is well qualified to speak on this subject. He says:

Roasting coffee is not so difficult a matter as is often claimed by operators and "experts" who seek thus to magnify their importance; but it is nevertheless a process about which a great deal may be learned in the school of practical experience. With one of our modern machines anybody with ordinary intelligence and nerve can take off a roast after one trial which would pass muster in many establishments, but that same person applying himself to the roasting job for a week will either be turning out vastly better roasts or will have demonstrated that he never can excel as a roasterman.

Modern coffee roasting machines provide for easy control of the heat (from coal, coke, or gas fuel), for constantly mixing the coffee in such a manner that the heat is transmitted uniformly to the entire batch, for carrying away all steam and smoke rapidly, for easy testing of the progress of the roast, and for immediate discharge when desired. The operator's problem therefore is the regulation of the heat and deciding just when the desired roasting has been accomplished.

If all coffees were alike, roasting would soon be almost automatic. In some plants most of the work is on one uniform grade or blend. But coffees which vary greatly in moisture-content, in flinty or spongy nature, and in various other characteristics, will puzzle the operator until he establishes a personal acquaintance with them in various combinations in repeated roasting operations. The roasterman therefore must be able to observe closely, to draw sensible conclusions, and to remember what he learns. Roasting coffee is work of a sort which anybody can do, which a few people can do really well, and no one so well but that further improvement is possible.

There is no absolute standard of what the best roasting results are. Some dealers want the coffee beans swelled up to the bursting point, while others would object to so showy a development. Some care nothing at all about appearance as compared with cup value, while others insist on a bright style even at some sacrifice of quality. Business judgment must decide what goods can be sold most profitably.

The loss of coffee in weight in the roasting operation, or shrinkage as it is called, is a matter which offers opportunities for false claims of advantage in roasting processes. Anybody can see that if just as good roasted coffee could be produced with a lessened shrinkage there would be a chance for a decided increase in profits. It is a sort of finding-money proposition which always turns out to be too good to be true. The purpose of roasting coffee is to produce an article entirely different from green coffee, which is accomplished mainly by driving out moisture. If coffee is roasted thoroughly, inside as well as outside, so as to give the greatest roasted coffee value, it must sustain a proper loss in weight which there is no legitimate way to avoid. The amount of shrinkage varies a great deal with the kind of coffee and its age, also with the kind of roasting desired.

Adding a little water to the coffee at the end of the operation has the advantage of checking the roast at the desired point and helping to swell and brighten the coffee, but it is a practice which is sometimes abused by soaking the coffee with water so as to reduce the shrinkage. This is done either dishonestly, to steal coffee which belongs to somebody else, or foolishly; for the heavier coffee has a lessened cup value which more than counterbalances the apparent gain.

A Typical Coal Roaster

A typical United States coal roaster is shown in the accompanying cut. It is the latest form of that type of Burns machine which requires a brickwork setting. The picture shows the roaster ready to operate, except for smoke pipe and power connections.

The front of the machine shown has a cast-iron plate having brackets which support the cylinder front bearing, and double fire doors below for the furnace and the ash pit. The movable part of the roaster is hidden by the front head, a heavy casting which stands still except when moved by hand through a half-turn for feeding and discharging.

The cylinder is driven by gears at the back, revolving constantly at uniform speed. The inside of the cylinder is arranged with reverse-spiral flanges which mix the coffee perfectly and make uneven roasting impossible; and they discharge promptly every grain of coffee when the front-head opening is turned to the lower position. The roaster is generally operated with coal fuel, but can be used with gas by installing a suitable burner under the cylinder.

| Cost Card for Roasters Showing the value added to the cost of green coffee by roasting By A.C. Aborn Basis: 16 percent Shrinkage. 3⁄4 cent a pound for Roasting. |

|||||||

| G = Cost Green, Cents per Lb. R = Cost Roasted, Cents per Lb. |

|||||||

| G | R | G | R | G | R | G | R |

| 5 | 6.85 | 12 | 15.18 | 19 | 23.51 | 26 | 31.85 |

| 51⁄8 | 6.99 | 121⁄8 | 15.33 | 191⁄8 | 23.66 | 261⁄8 | 31.99 |

| 51⁄4 | 7.14 | 121⁄4 | 15.48 | 191⁄4 | 23.81 | 261⁄4 | 32.14 |

| 53⁄8 | 7.29 | 123⁄8 | 15.63 | 193⁄8 | 23.96 | 263⁄8 | 32.29 |

| 51⁄2 | 7.44 | 121⁄2 | 15.77 | 191⁄2 | 24.11 | 261⁄2 | 32.44 |

| 55⁄8 | 7.59 | 125⁄8 | 15.92 | 195⁄8 | 24.26 | 265⁄8 | 32.59 |

| 53⁄4 | 7.74 | 123⁄4 | 16.07 | 193⁄4 | 24.40 | 263⁄4 | 32.74 |

| 57⁄8 | 7.89 | 127⁄8 | 16.22 | 197⁄8 | 24.55 | 267⁄8 | 32.89 |

| 6 | 8.04 | 13 | 16.37 | 20 | 24.70 | 27 | 33.04 |

| 61⁄8 | 8.19 | 131⁄8 | 16.52 | 201⁄8 | 24.85 | 271⁄8 | 33.18 |

| 61⁄4 | 8.33 | 131⁄4 | 16.67 | 201⁄4 | 25.00 | 271⁄4 | 33.33 |

| 63⁄8 | 8.48 | 133⁄8 | 16.82 | 203⁄8 | 25.15 | 273⁄8 | 33.48 |

| 61⁄2 | 8.63 | 131⁄2 | 16.97 | 201⁄2 | 25.30 | 271⁄2 | 33.63 |

| 65⁄8 | 8.78 | 135⁄8 | 17.11 | 205⁄8 | 25.45 | 275⁄8 | 33.78 |

| 63⁄4 | 8.93 | 133⁄4 | 17.26 | 203⁄4 | 25.60 | 273⁄4 | 33.93 |

| 67⁄8 | 9.08 | 137⁄8 | 17.41 | 207⁄8 | 25.75 | 277⁄8 | 34.08 |

| 7 | 9.23 | 14 | 17.56 | 21 | 25.89 | 28 | 34.23 |

| 71⁄8 | 9.37 | 141⁄8 | 17.71 | 211⁄8 | 26.04 | 281⁄8 | 34.38 |

| 71⁄4 | 9.52 | 141⁄4 | 17.86 | 211⁄4 | 26.19 | 281⁄4 | 34.52 |

| 73⁄8 | 9.67 | 143⁄8 | 18.01 | 213⁄8 | 26.34 | 283⁄8 | 34.67 |

| 71⁄2 | 9.82 | 141⁄2 | 18.15 | 211⁄2 | 26.49 | 281⁄2 | 34.82 |

| 75⁄8 | 9.97 | 145⁄8 | 18.30 | 215⁄8 | 26.64 | 285⁄8 | 34.97 |

| 73⁄4 | 10.12 | 143⁄4 | 18.45 | 213⁄4 | 26.79 | 283⁄4 | 35.12 |

| 77⁄8 | 10.27 | 147⁄8 | 18.60 | 217⁄8 | 26.93 | 287⁄8 | 35.27 |

| 8 | 10.42 | 15 | 18.75 | 22 | 27.08 | 29 | 35.42 |

| 81⁄8 | 10.57 | 151⁄8 | 18.90 | 221⁄8 | 27.23 | 291⁄8 | 35.57 |

| 81⁄4 | 10.71 | 151⁄4 | 19.05 | 221⁄4 | 27.38 | 291⁄4 | 35.71 |

| 83⁄8 | 10.86 | 153⁄8 | 19.20 | 223⁄8 | 27.53 | 293⁄8 | 35.86 |

| 81⁄2 | 11.01 | 151⁄2 | 19.35 | 221⁄2 | 27.68 | 291⁄2 | 36.01 |

| 85⁄8 | 11.16 | 155⁄8 | 19.49 | 225⁄8 | 27.83 | 295⁄8 | 36.16 |

| 83⁄4 | 11.31 | 153⁄4 | 19.64 | 223⁄4 | 27.98 | 293⁄4 | 36.31 |

| 87⁄8 | 11.46 | 157⁄8 | 19.79 | 227⁄8 | 28.13 | 297⁄8 | 36.46 |

| 9 | 11.61 | 16 | 19.94 | 23 | 28.27 | 30 | 36.61 |

| 91⁄8 | 11.76 | 161⁄8 | 20.09 | 231⁄8 | 28.42 | 301⁄8 | 36.76 |

| 91⁄4 | 11.90 | 161⁄4 | 20.24 | 231⁄4 | 28.57 | 301⁄4 | 36.90 |

| 93⁄8 | 12.05 | 163⁄8 | 20.39 | 233⁄8 | 28.72 | 303⁄8 | 37.05 |

| 91⁄2 | 12.20 | 161⁄2 | 20.54 | 231⁄2 | 28.87 | 301⁄2 | 37.20 |

| 95⁄8 | 12.35 | 165⁄8 | 20.68 | 235⁄8 | 29.02 | 305⁄8 | 37.35 |

| 93⁄4 | 12.50 | 163⁄4 | 20.83 | 233⁄4 | 29.17 | 303⁄4 | 37.50 |

| 97⁄8 | 12.65 | 167⁄8 | 20.98 | 237⁄8 | 29.32 | 307⁄8 | 37.65 |

| 10 | 12.80 | 17 | 21.13 | 24 | 29.46 | 31 | 37.80 |

| 101⁄8 | 12.95 | 171⁄8 | 21.28 | 241⁄8 | 29.61 | 311⁄8 | 37.95 |

| 101⁄4 | 13.10 | 171⁄4 | 21.43 | 241⁄4 | 29.76 | 311⁄4 | 38.10 |

| 103⁄8 | 13.24 | 173⁄8 | 21.58 | 243⁄8 | 29.91 | 313⁄8 | 38.24 |

| 101⁄2 | 13.39 | 171⁄2 | 21.73 | 241⁄2 | 30.06 | 311⁄2 | 38.39 |

| 105⁄8 | 13.54 | 175⁄8 | 21.87 | 245⁄8 | 30.21 | 315⁄8 | 38.54 |

| 103⁄4 | 13.69 | 173⁄4 | 22.02 | 243⁄4 | 30.36 | 313⁄4 | 38.69 |

| 107⁄8 | 13.84 | 177⁄8 | 22.17 | 247⁄8 | 30.51 | 317⁄8 | 38.84 |

| 11 | 13.99 | 18 | 22.32 | 25 | 30.65 | 32 | 38.90 |

| 111⁄8 | 14.14 | 181⁄8 | 22.47 | 251⁄8 | 30.80 | 321⁄8 | 39.14 |

| 111⁄4 | 14.29 | 181⁄4 | 22.62 | 251⁄4 | 30.95 | 321⁄4 | 39.29 |

| 113⁄8 | 14.43 | 183⁄8 | 22.77 | 253⁄8 | 31.10 | 323⁄8 | 39.43 |

| 111⁄2 | 14.58 | 181⁄2 | 22.92 | 251⁄2 | 31.25 | 321⁄2 | 39.58 |

| 115⁄8 | 14.73 | 185⁄8 | 23.07 | 255⁄8 | 31.40 | 325⁄8 | 39.73 |

| 113⁄4 | 14.88 | 183⁄4 | 23.21 | 253⁄4 | 31.55 | 323⁄4 | 39.88 |

| 117⁄8 | 15.03 | 187⁄8 | 23.36 | 257⁄8 | 31.70 | 327⁄8 | 40.03 |