CHAPTER II. EARTHWORKS—ENCLOSURES.

The Enclosures, or, as they are familiarly called throughout the West, “Forts,” constitute a very important and interesting class of remains. Their dimensions, and the popular opinion as to their purposes, attract to them more particularly the attention of observers. As a consequence, most that has been written upon our antiquities relates to them. A considerable number have been surveyed and described by different individuals, at different times; but no systematic examination of a sufficient number to justify any general conclusion as to their origin and purposes has heretofore been attempted. We have therefore had presented as many different hypotheses as there have been individual explorers; one maintaining that all the enclosures were intended for defence, while another persists that none could possibly have been designed for any such purpose. Investigation has shown, however, that while certain works possess features demonstrating incontestibly a military origin, others were connected with the superstitions of the builders, or designed for other purposes not readily apparent in our present state of knowledge concerning them.

It has already been remarked that the square and the circle, separate or in combination, were favorite figures with the mound-builders; and a large proportion of their works in the Scioto valley, and in Ohio generally, are of these forms. Most of the circular works are small, varying from two hundred and fifty to three hundred feet in diameter, while others are a mile or more in circuit. Some stand isolated, but most in connection with one or more mounds, of greater or less dimensions, or in connection with other more complicated works. Wherever the circles occur, if there be a fosse, or ditch, it is almost invariably interior to the parapet. Instances are frequent where no ditch is discernible, and where it is evident that the earth composing the embankment was brought from a distance, or taken up evenly from the surface. In the square and in the irregular works, if there be a fosse at all, it is exterior to the embankment; except in the case of fortified hills, where the earth, for the best of reasons, is usually thrown from the interior. These facts are not without their importance in determining the character and purpose of these remains. Another fact, bearing directly upon the degree of knowledge possessed by the builders, is, that many, if not most, of the circular works are perfect circles, and that many of the rectangular works are accurate squares. This fact has been demonstrated, in numerous instances, by careful admeasurements; and has been remarked in cases where the works embrace an area of many acres, and where the embankments, or circumvallations, are a mile and upwards in extent. p009

To facilitate description, and to bring something like system out of the disordered materials before us, the enclosures are, to as great a degree as practicable, divided into classes; that is to say, such as are esteemed to be works of defence are placed together, while those which are regarded as sacred, or of a doubtful character, come under another division.

WORKS OF DEFENCE.

Those works which are incontestibly defensive usually occupy strong natural positions; and to understand fully their character, their capability for defence, and the nature of their entrenchments, it is necessary to notice briefly the predominant features of the country in which they occur. The valley of the Mississippi river, from the Alleghanies to the ranges of the Rocky Mountains, is a vast sedimentary basin, and owes its general aspect to the powerful agency of water. Its rivers have worn their valleys deep into a vast original plain; leaving, in their gradual subsidence, broad terraces, which mark the eras of their history. The edges of the table-lands, bordering on the valleys, are cut by a thousand ravines, presenting bluff headlands and high hills with level summits, sometimes connected by narrow isthmuses with the original table, but occasionally entirely detached. The sides of these elevations are generally steep, and difficult of access; in some cases precipitous and absolutely inaccessible. The natural strength of such positions, and their susceptibility of defence, would certainly suggest them as the citadels of a people having hostile neighbors, or pressed by invaders. Accordingly we are not surprised at finding these heights occupied by strong and complicated works, the design of which is no less indicated by their position than by their construction. But in such cases, it is always to be observed, that they have been chosen with great care, and that they possess peculiar strength, and have a special adaptation for the purposes to which they were applied. They occupy the highest points of land, and are never commanded from neighboring positions. While rugged and steep on most sides, they have one or more points of comparatively easy approach, in the protection of which the utmost skill of the builders seems to have been exhausted. They are guarded by double, overlapping walls, or a series of them, having sometimes an accompanying mound, designed perhaps for a look-out, and corresponding to the barbican in the system of defence of the Britons of the middle era. The usual defence is a simple embankment, thrown up along and a little below the brow of the hill, varying in height and solidity, as the declivity is more or less steep and difficult of access.

Other defensive works occupy the peninsulas created by the rivers and large p010 streams, or cut off the headlands formed by their junction with each other. In such cases a fosse and wall are thrown across the isthmus, or diagonally from the bank of one stream to the bank of the other. In some, the wall is double, and extends along the bank of the stream some distance inwardly, as if designed to prevent an enemy from turning the flanks of the defence.

To understand clearly the nature of the works last mentioned, it should be remembered that the banks of the western rivers are always steep, and where these works are located, invariably high. The banks of the various terraces are also steep, and vary from ten to thirty and more feet in height. The rivers are constantly shifting their channels; and they frequently cut their way through all the intermediate up to the earliest-formed, or highest terrace, presenting bold banks, inaccessibly steep, and from sixty to one hundred feet high. At such points, from which the river has, in some instances, receded to the distance of half a mile or more, works of this description are oftenest found.

And it is a fact of much importance, and worthy of special note, that within the scope of a pretty extended observation, no work of any kind has been found occupying the first, or latest-formed terrace. This terrace alone, except at periods of extraordinary freshets, is subject to overflow.8 The formation of each terrace constitutes a sort of semi-geological era in the history of the valley; and the fact that none of the ancient works occur upon the lowest or latest-formed of these, while they are found indiscriminately upon all the others, bears directly upon the question of their antiquity.

In addition to the several descriptions of defensive works above enumerated, there are others presenting peculiar features, which will be sufficiently noticed in the plans and explanations that follow. These plans are all drawn from actual and minute, and in most instances personal survey, and are presented, unless otherwise specially noted, on a uniform scale of five hundred feet to the inch. When there are interesting features too minute to be satisfactorily indicated on so small a scale, enlarged plans have been adopted. This is the case with the very first plan presented. Sections and supplementary plans are given, whenever it is supposed they may illustrate the description, or assist the comprehension of the reader. To shorten the text, the admeasurements are often placed upon the plans, and the “Field Books” of survey wholly omitted. The greatest care has, in all cases, been taken to secure perfect fidelity in all essential particulars. In the sectional maps, in order to show something of the character as well as the positions of the works, it has been found necessary to exaggerate them beyond their proportionate size. Some of the minor features of a few works are also slightly exaggerated, but in no case where it would be apt to lead to misapprehension or wrong conceptions of their character. p011

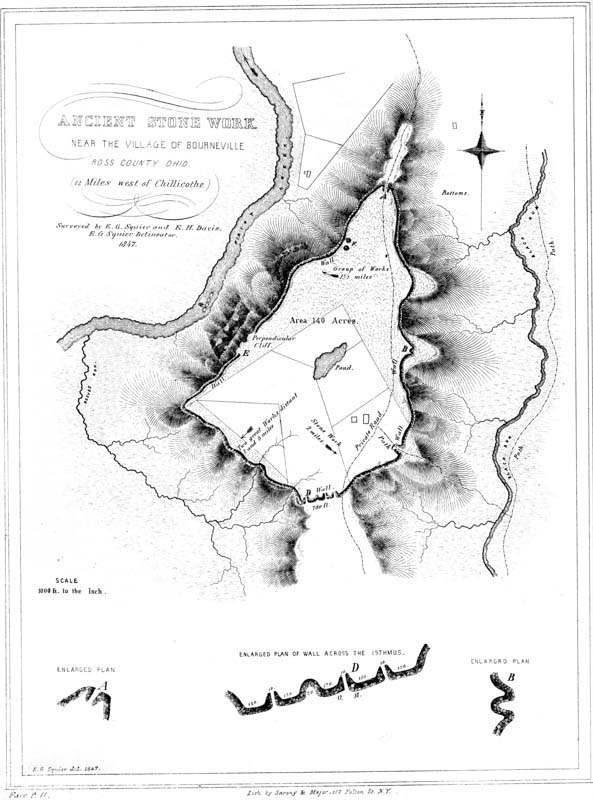

♠ IV. Ancient Stone Work near the village of Bourneville, Ross Co. Ohio, 12 miles west of Chillicothe.

PLATE IV.9 STONE WORK, NEAR BOURNEVILLE, ROSS COUNTY, OHIO.

This work occupies the summit of a lofty, detached hill, twelve miles westward from the city of Chillicothe, near the village of Bourneville. The hill is not far from four hundred feet in perpendicular height; and is remarkable, even among the steep hills of the West, for the general abruptness of its sides, which at some points are absolutely inaccessible. It is the advance point of a range of hills, situated between the narrow valleys of two small creeks; and projects midway into the broad valley of Paint creek, so as to constitute its most prominent natural feature. It is a conspicuous object from every point of view. Its summit is a wide and fertile plain, with occasional considerable depressions, some of which contain water during the entire year.

The defences consist of a wall of stone which is carried around the hill, a little below the brow; but at some places it rises, so as to cut off the narrow spurs, and extends across the neck that connects the hill with the range beyond. It should not be understood by the term wall, that, at this time, anything like a wall of stones regularly laid up exists; on the contrary, where the line is best preserved, there is little evidence that the stones were laid one upon the other so as to present vertical faces, much less that they were cemented in place. At a few points, however, more particularly at the isthmus D, there are some indications of arrangement in the stones, tending to the belief that the wall here may have been regularly faced on the exterior. The appearance of the line, for the most part, is just what might be expected from the falling outwards of a wall of stones placed, as this was, upon the declivity of a hill. Upon the western, or steepest face of the hill, the range of stones covers a space varying from thirty to fifty feet in width, closely resembling the “protection walls” carried along the embankments of rail-roads and canals, where exposed to the action of rivers or large streams. But for the amount of stones, it might be taken for a natural feature,—the debris of the out-cropping sand strata. Such, certainly, is the first impression which it produces upon the visitor; an impression, however, which is speedily corrected upon reaching the points where the supposed line of debris, rising upon the spurs, forms curved gateways, and then resumes its course as before.

Upon the eastern face of the hill, where the declivity is least abrupt, the wall is heavier and more distinct than upon the west, resembling a long stone-heap of fifteen or twenty feet base, and from three to four feet in height. Where it crosses the isthmus it is heaviest; and although stones enough have been removed from it, p012 at that point, to build a stout division wall between the lands of two proprietors, their removal is not discoverable. This isthmus is seven hundred feet wide, and the wall is carried in a right line across it, at its narrowest point. Here are three gateways opening upon the continuous terrace beyond. These are formed by the curving inward of the ends of the wall for forty or fifty feet, leaving narrow pass-ways between, not exceeding eight feet in width. At the other points, A and C of the plan, where there are jutting ridges, are similar gateways. It is at these points that the hill is most easy of access. At A is a modern roadway; at C is a pathway leading down into the valley of “Black Run.” At B appears to have been a similar gateway, which for some reason was closed up; a like feature may be observed in the line D. At the gateways, the amount of stones is more than quadruple the quantity at other points, constituting broad, mound-shaped heaps. They also exhibit the marks of intense heat, which has in some instances vitrified their surfaces, and fused them together. Light, porous scoriæ are abundant in the centres of some of these piles. Indeed, strong traces of fire are visible at many places on the line of the wall, particularly at F, the point commanding the broadest extent of country. Here are two or three small mounds of stone, which seem burned throughout. Nothing is more certain than that powerful fires have been maintained, for considerable periods, at numerous prominent points on the hill; for what purposes, unless as alarm signals, it is impossible to conjecture.10

It will be observed that the wall is interrupted for some distance at E, where the hill is precipitous and inaccessible. There are, as has already been remarked, several depressions upon the hill which contain constant supplies of water. One of them covers about two acres, and furnishes a supply estimated by the proprietor as adequate to the wants of a thousand head of cattle. Water is obtained in abundance at the depth of twenty feet.

The area enclosed within this singular work is something over one hundred and forty acres, and the line of the wall measures upwards of two and a quarter miles in length. Most of the wall, and a large portion of the area, are still covered with a heavy primitive forest. Trees of the largest size grow on the line, twisting their roots among the stones, some of which are firmly imbedded in their trunks.

That this work was designed for defence, will hardly admit of doubt; the fact is sufficiently established, not less by the natural strength of the position, than by the character of the defences. Of the original construction of the wall, now so completely in ruins, we can of course form no very clear conception. It is possible that it was once regularly laid up; but it seems that, if such were ever the case, some satisfactory evidence of the fact would still be discoverable. We must consider, however, that it is situated upon a yielding and disintegrating declivity; and that successive forests, in their growth and prostration, aided by the action of the elements, in the long period which must certainly have elapsed since its p013 construction, would have been adequate to the total demolition of structures more solid and enduring than we are justified in supposing any of the stone works of the ancient people to have been. The stones are of all sizes, and sufficiently abundant to have originally formed walls eight feet high, by perhaps an equal base. At some points, substantial fence-lines have been built from them, without sensibly diminishing their numbers. It can readily be perceived that, upon a steep declivity, such as this hill presents, so large an amount of stones, even though simply heaped together, must have proved an almost insurmountable impediment in the way of an assailant, especially if they were crowned by palisades.

In the magnitude of the area enclosed, this work exceeds any hill-work now known in the country; although the wall is considerably less in length than that of “Fort Ancient,” on the Little Miami river. It evinces great labor, and bears the impress of a numerous people. The valley in which it is situated was a favorite one with the race of the mounds; and the hill overlooks a number of extensive groups of ancient works, the bearings of which are indicated by arrows on the plan.

Paint creek washes the base of the hill upon the left, and has for some distance worn away the argillaceous slate rock, so as to leave a mural front of from fifty to seventy-five feet in height. It has also uncovered a range of septaria, occurring near the base of the slate stratum; a number of which, of large size, are to be seen in the bed of the creek, at a. These, most unaccountably, have been mistaken for works of art,—“stone covers” for deep wells sunk in the rock. This notion has been gravely advanced in print; and the humble septaria, promoted to a high standing amongst the antiquities of America, now figure prominently in every work of speculations on the subject. The reason for sinking wells in the bed of a creek, was probably never very obvious to any mind. The supposed “wells” are simple casts of huge septaria, which have been dislodged from their beds; the cyclopean “covers” are septaria which have resisted the disintegrating action of the water, and still retain their places. Parallel ranges of these singular natural productions run through the slate strata of this region: they are of an oblate-spheroidal figure, some of them measuring from nine to twelve feet in circumference. They frequently have apertures or hollows in their middle, with radiating fissures, filled with crystalline spar or sulphate of baryta. These fissures sometimes extend beyond them, in the slate rock, constituting the “good joints” mentioned by some writers. The slate layers are not interrupted by these productions, but are bent or wrapped around them. The following cut illustrates their character. A is a vertical section: a exhibiting the water, b the rock. At c the septarium has disintegrated, or has been removed, and its cavity or bed is filled with pebbles. At d the nodule still remains. B exhibits the appearance presented by d from above.

A stone work, somewhat similar in character to that here described, exists near the town of Somerset, Perry county, Ohio. It is described by Mr. Atwater in the Archæologia Americana, vol. i. p. 131. p014

Still another, of small size and irregular outline, is situated on Beaver creek, a branch of the Great Kenhawa, in Fayette county, Virginia, of which an account was published by Mr. I. Craig of Pittsburgh, in the “American Pioneer,” vol. i. p. 199.

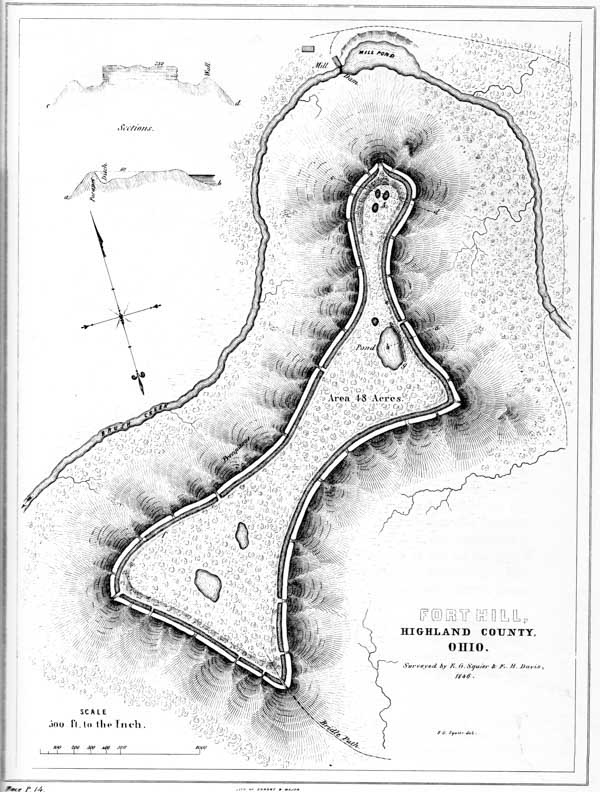

PLATE V. “FORT HILL,” HIGHLAND COUNTY, OHIO.11

This work occurs in the southern part of Highland county, Ohio; and is distant about thirty miles from Chillicothe, and twelve from Hillsborough. It is universally known as “Fort Hill,” though no better entitled to the name than many others of similar character. The defences occupy the summit of a hill, which is elevated five hundred feet above the bed of Brush creek at its base, and eight hundred feet above the Ohio river at Cincinnati. Unlike the hills around it, this one stands detached and isolated, and forms a conspicuous object from every approach. Its sides are steep and precipitous; and, except at one or two points, if not absolutely inaccessible, extremely difficult of ascent. The points most easy of access are at the southern and northern angles, and may be reached on horseback. The top of the hill is level, and has an area of not far from fifty acres, which is covered with a heavy primitive forest of gigantic trees. One of these, a chestnut, standing on the embankment near the point indicated by the letter e, measures twenty-one feet in circumference; another, an oak, which also stood on the wall, at the point f, though now fallen and much decayed, still measures twenty-three feet in circumference. All around are scattered the trunks of immense trees, in every stage of decay; the entire forest presenting an appearance of the highest antiquity.

♠ V. Fort Hill, Highland Co. Ohio.

Thus much for its natural features. Running along the edge of the hill is an embankment of mingled earth and stone, interrupted at intervals by gateways. Interior to this is a ditch, from which the material composing the wall was taken. The length of the wall is eight thousand two hundred and twenty-four feet, or something over a mile and a half. In height, measuring from the bottom of the ditch, it varies from six to ten feet, though at some places it rises to the height of fifteen feet. Its average base is thirty-five or forty feet. It is thrown up somewhat below the brow of the hill, the level of the terrace being generally about even with the top of the wall; but in some places it rises considerably above, as shown in the sections. The outer slope of the wall is more abrupt than that of the hill; the earth and stones from the ditch, sliding down fifty or a hundred feet, have formed a p015 declivity for that distance, so steep as to be difficult of ascent, even with the aid which the trees and bushes afford. The ditch has an average width of not far from fifty feet; and, in many places, is dug through the sandstone layer upon which the soil of the terrace rests.12 At the point A, the rock is quarried out, leaving a mural front about twenty feet high. The inner declivity of the ditch appears to have been terraced. It descends abruptly from the level for a few feet, then declines gently for some distance, and again dips suddenly, as it approaches the wall. The vertical section a b exhibits this feature.

There are thirty-three gateways or openings in the wall, most of them very narrow, not exceeding fifteen or twenty feet in width at the top: only eleven of these have corresponding causeways across the ditch. They occur at irregular intervals; and some of them appear to have been rather designed to let off the water which might otherwise accumulate in the ditch, than to serve as places of egress or ingress. Indeed, most of them cannot be supposed to have been used for the last named purposes, inasmuch as they occur upon the very steepest points of the hill, and where approach is almost impossible. At the northern and southern spurs or angles of the hill, the gateways are widest, and the parapet curves slightly outwards. The ditch is interrupted at these points.

There are three depressions or ponds within the enclosure; the largest of these, g, has a well-defined artificial embankment on its lower side, which has recently been cut through, and the water principally drawn off. When full, the water must have covered very nearly an acre. Bog-clumps are growing around its edges, and it is free from trees. It does not seem to have any perennial sources of supply. There are several other small circular depressions, a number of which occur together at the bluff A; there are also traces of other excavations, not clearly defined, at various points on the hill.

An inspection of the plan of the work, shows that it is naturally divided into three parts; that at A being, in many respects, the most remarkable. It is connected with the main body of the work by a narrow ridge but one hundred feet wide, and terminates at a bold, bluff ledge, the top of which is thirty feet above the bottom of the trench, and twenty feet above the wall. This bluff is two hundred feet wide. It is altogether the most prominent point of the hill, and commands a wide extent of country. Here are strong traces of the action of fire on the rocks and stones; though whether remote or recent, it is not easy to determine. The connection between the two principal divisions of the work is also narrow, being barely two hundred and fifty feet in width.

Such are the more striking features of this interesting work. Considered in a military point of view, as a work of defence, it is well chosen, well guarded, and, with an adequate force, impregnable to any mode of attack practised by a rude, or semi-civilized people. As a natural stronghold, it has few equals; and the p016 degree of skill displayed and the amount of labor expended in constructing its artificial defences, challenge our admiration, and excite our surprise. With all the facilities and numerous mechanical appliances of the present day, the construction of a work of this magnitude would be no insignificant undertaking. And when we reflect how comparatively rude, at the best, must have been the means at the command of the people who raised this monument, we are prepared to estimate the value which they placed upon the objects sought in its erection, and also to form some conclusion respecting the number and character of the people themselves.

It is quite unnecessary to recapitulate the features which give to this the character of a military work; for they are too obvious to escape attention. The angles of the hill form natural bastions, enfilading the wall. The position of the wall, the structure of the ditch, the peculiarities of the gateways where ascent is practicable, the greater height of the wall where the declivity of the hill is least abrupt, the reservoirs of water, the look-out or citadel, all go to sustain the conclusion.

The evidence of antiquity afforded by the aspect of the forest, is worthy of more than a passing notice. Actual examination showed the existence of not far from two hundred annual rings or layers to the foot, in the large chestnut-tree already mentioned, now standing upon the entrenchments. This would give nearly six hundred years as the age of the tree. If to this we add the probable period intervening from the time of the building of the work to its abandonment, and the subsequent period up to its invasion by the forest, we are led irresistibly to the conclusion, that it has an antiquity of at least one thousand years.13 But when we notice, all around us, the crumbling trunks of trees half hidden in the accumulating soil, we are induced to fix upon an antiquity still more remote.

It is worthy of note, that this work is in a broken country, with no other remains, except perhaps a few small, scattered mounds, in its vicinity. The nearest monuments of magnitude are in the Paint creek valley, sixteen miles distant, from which it is separated by elevated ridges. Lower down, on Brush creek, towards its junction with the Ohio, are some works; but none of importance occur within twelve miles in that direction.

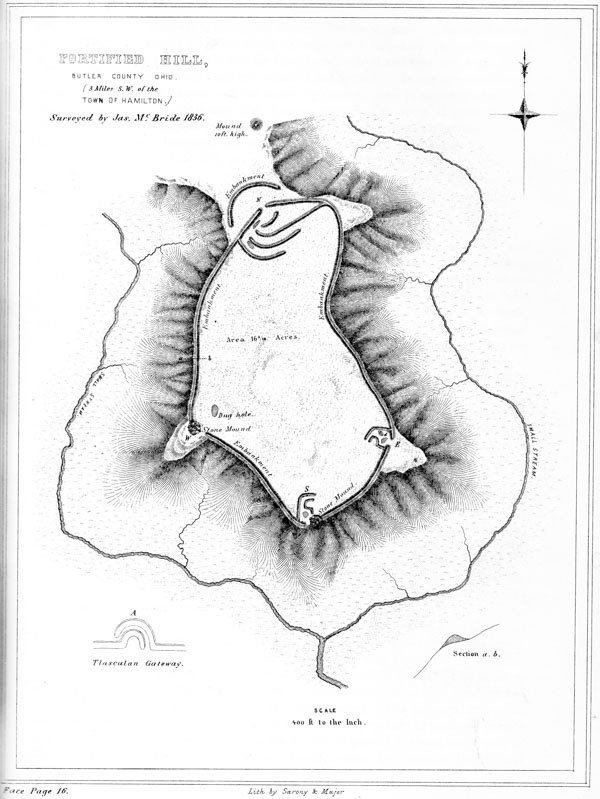

♠ VI. Fortified Hill, Butler Co. Ohio, 3 Mile S. W. of the town of Hamilton.

PLATE VI. FORTIFIED HILL, BUTLER COUNTY, OHIO.

This fine work is situated in Butler county, Ohio, on the west side of the Great Miami river, three miles below the town of Hamilton. The plan is from a p017 survey by JAMES MCBRIDE, Esq., and the description is made up from his notes. The hill, the summit of which it occupies, is about a half mile distant from the present bed of the river, and is not far from two hundred and fifty feet high, being considerably more elevated than any other in the vicinity. It is surrounded at all points, except a narrow space at the north, by deep ravines, presenting steep and almost inaccessible declivities. The descent towards the north is gradual; and from that direction, the hill is easy of access. It is covered with a primitive forest of oak, hickory, and locust, of the same character with the surrounding forests.

Skirting the brow of the hill, and generally conforming to its outline, is a wall of mingled earth and stone, having an average height of five feet by thirty-five feet base. It has no accompanying ditch; the earth composing it, which is a stiff clay, having been for the most part taken up from the surface, without leaving any marked excavation. There are a number of “dug holes,” however, at various points, from which it is evident a portion of the material was obtained. The wall is interrupted by four gateways or passages, each twenty feet wide; one opening to the north, on the approach above mentioned, and the others occurring where the spurs of the hill are cut off by the parapet, and where the declivity is least abrupt. They are all, with one exception, protected by inner lines of embankment, of a most singular and intricate description. These are accurately delineated in the plan, which will best explain their character. It will be observed that the northern gateway, in addition to its inner maze of walls, has an exterior work of a crescent shape, the ends of which approach to within a few feet of the brow of the hill.

The excavations are uniformly near the gateways, or within the lines covering them. None of them are more than sixty feet over, nor have they any considerable depth. Nevertheless, they all, with the exception of the one nearest to gateway S, contain water for the greater portion, if not the whole of the year. A pole may be thrust eight or ten feet into the soft mud, at the bottom of those at E.

At S and W, terminating the parapet, are two mounds, each eight feet high, composed of stones thrown loosely together. Thirty rods distant from gateway N, and exterior to the work, is a mound ten feet high, on which trees of the largest size are growing. It was partially excavated a number of years ago, and a quantity of stones taken out, all of which seemed to have undergone the action of fire.

The ground in the interior of this work gradually rises, as indicated in the section, to the height of twenty-six feet above the base of the wall, and overlooks the entire adjacent country.

In the vicinity of this work, are a number of others occupying the valley; no less than six of large size occur within a distance of six miles down the river. [See Plate III. No. 2. This work is marked A on the map.]

The character of this structure is too obvious to admit of doubt. The position which it occupies is naturally strong, and no mean degree of skill is employed in its artificial defences. Every avenue is strongly guarded. The principal approach, the only point easy of access, or capable of successful assault, is rendered doubly secure. A mound, used perhaps as an alarm post, is placed at about one-fourth of the distance down the ascent; a crescent wall crosses the isthmus, leaving but p018 narrow passages between its ends and the steeps on either hand. Next comes the principal wall of the enclosure. In event of an attack, even though both these defences were carried, there still remains a series of walls so complicated as inevitably to distract and bewilder the assailants, thus giving a marked advantage to the defenders. This advantage may have been much greater than we, in our ignorance of the military system of this ancient people, can understand. But, from the manifest judgment with which their defensive positions were chosen, as well as from the character of their entrenchments, so far as we comprehend them, it is safe to conclude that all parts of this work were the best calculated to secure the objects proposed by the builders, under the modes of attack and defence then practised.

The coincidences between the guarded entrances of this and similar works throughout the West, and those of the Mexican defences, is singularly striking. The wall on the eastern side of the Tlascalan territories, mentioned by Cortez and Bernal Diaz, was six miles long, having a single entrance thirty feet wide, which was formed in the manner represented in the supplementary plan A. The ends of the wall overlapped each other, in the form of semicircles, having a common centre.14

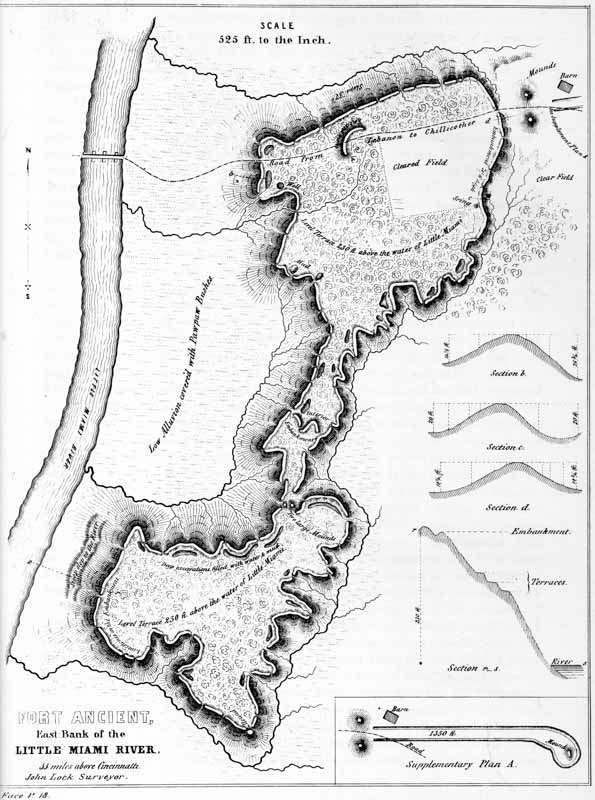

PLATE VII. “FORT ANCIENT,” WARREN COUNTY, OHIO.15

♠ VII. Fort Ancient, East Bank of the Little Miami River, 33 miles above Cincinnati.

One of the most extensive, if not the most extensive, work of this class, in the entire West, occurs on the banks of the Little Miami river, about thirty-five miles north-east from Cincinnati, in Warren county, Ohio. It has not far from four miles of embankment, for the most part very heavy, rising, at the more accessible points, to the height of eighteen and twenty feet. The accompanying map is from a faithful survey, made by Prof. LOCKE, of Cincinnati, and published by him amongst the papers of the American Association of Geologists and Naturalists, in p019 1843. One or two slight additions have been made to his map, to indicate features which may be of some importance in a consideration of the work and its character. The description of Prof. Locke, accompanying the map, though brief, and written with a view to certain geological questions, may not be omitted in this connection.

“This work occupies a terrace on the left bank of the river, and two hundred and thirty feet above its waters. The place is naturally a strong one, being a peninsula, defended by two ravines, which, originating on the east side near to each other, diverging and sweeping around, enter the Miami, the one above, the other below the work. The Miami itself, with its precipitous bank of two hundred feet, defends the western side. The ravines are occupied by small streams. Quite around this peninsula, on the very verge of the ravines, has been raised an embankment of unusual height and perfection. Meandering around the spurs, and re-entering to pass the heads of the gullies, it is so winding in its course that it required one hundred and ninety-six stations to complete its survey. The whole circuit of the work is between four and five miles. The number of cubic yards of excavation may be approximately estimated at six hundred and twenty-eight thousand eight hundred. The embankment stands in many places twenty feet in perpendicular height; and although composed of a tough, diluvial clay, without stone, except in a few places, its outward slope is from thirty-five to forty-three degrees. This work presents no continuous ditch; but the earth for its construction has been dug from convenient pits, which are still quite deep, or filled with mud and water. Although I brought over a party of a dozen active young engineers, and we had encamped upon the ground to expedite our labors, we were still two days in completing our survey, which, with good instruments, was conducted with all possible accuracy. The work approaches nowhere within many feet of the river; but its embankment is, in several places, carried down into ravines from fifty to one hundred feet deep, and at an angle of thirty degrees, crossing a streamlet at the bottom, which, by showers, must often swell to a powerful torrent. But in all instances the embankment may be traced to within three to eight feet of the stream. Hence it appears, that although these little streams have cut their channels through fifty to one hundred feet of thin, horizontal layers of blue limestone, interstratified with indurated clay marl, not more than three feet of that excavation has been done since the construction of the earthworks. If the first portion of the denudation was not more rapid than the last, a period of at least thirty to fifty thousand years would be required for the present point of its progress. But the quantity of material removed from such a ravine is as the square of its depth, which would render the last part of its denudation much slower, in vertical descent, than the first part. That our streams have not yet reached their ultimate level, a point beyond which they cease to act upon their beds, is evident from the vast quantity of solid material transported annually by our rivers, to be added to the great delta of the Mississippi. Finally, I am astonished to see a work, simply of earth, after braving the storms of thousands of years, still so entire and well marked. Several circumstances have contributed to this. The clay of which it is built is not easily penetrated by water. The bank has been, and is still, mostly covered by a forest p020 of beech trees, which have woven a strong web of their roots over its steep sides; and a fine bed of moss (Polytrichum) serves still further to afford protection.”

Upon the steep slope of the hill, at the point where it approaches nearest to the river, are distinctly traceable three parallel terraces, which were not represented in the original map, but which are indicated here. It is not impossible that they are natural, and were formed by successive slips or slides of earth, a feature not uncommon at the West. They nevertheless, from their great regularity, appear to be artificial, and are so regarded by most persons. A very fine view of the valley, in both directions, is commanded from them; though, perhaps, no better than may be obtained from the brow of the hill along which the embankment runs. It has been suggested that they were designed as stations, from which to annoy an enemy passing in boats or canoes along the river. This feature is illustrated in the section r s.

From a point near the two large mounds on the neck of the peninsula, start off two parallel walls, which continue for about thirteen hundred and fifty feet, when they diverge suddenly, but soon close around a small mound. As this outwork is in cultivated grounds, it has been so much obliterated as to escape ordinary observation, and is now traceable with difficulty. These parallels are shown in the Supplementary Plan A. They are almost identical, in all their dimensions, with similar parallels attached to ancient works in the Scioto valley.

It is a feature no less worthy of remark in this than in other works of the same class, and one which bears directly upon the question of their design, that at all the more accessible points, the defences are of the greatest solidity and strength. Across the isthmus connecting this singular peninsula with the table land, the wall is nearly double the height that it possesses at those points where the conformation of the ground assisted the builders in securing their position. The average height of the embankment is between nine and ten feet; but, at the place mentioned, it is no less than twenty. At the spur where the State road ascends the hill, and where the declivity is most gentle, the embankment is also increased in height and solidity, being at this time not less than fourteen feet high by sixty feet base.

There are over seventy gateways or interruptions in the embankment, at irregular intervals along its line. For reasons heretofore given, it is difficult to believe they were all designed as places of ingress or egress. We can only account for their number, upon the hypothesis that they are places once occupied by block-houses or bastions composed of timber, and which have long since decayed. These openings appear to have been originally about ten or fifteen feet in width.

- ♠

VIII. Ancient Works

Nos. 1–2. Butler Co. Ohio.

No. 3. Miami Co. Ohio.

No. 4. Montgomery Co. Ohio.

This work, it will be seen, consists of two grand divisions, the passage between which is long and narrow. Across this neck is carried a wall of the ordinary dimensions, as if to prevent the further progress of an enemy, in the event of either of the principal divisions being carried,—a feature which, while it goes to establish the military origin of the work, at the same time evinces the skill and foresight of the builders. This foresight is further shown, in so managing the excavations necessary for the erection of the walls, as to form numerous large reservoirs; sufficient, in p021 connection with the springs originating within the work, to supply with water any population which might here make a final stand before an invader. Even in the absence of these sources, surrounded as the work is on every hand by streams, it would be easy, in face of the most formidable investment, to procure an adequate supply.

At numerous points in the line of embankment, and where from position they would yield the most effective support, are found large quantities of stones. These are water-worn, and seem, for the most part, to have been taken from the river. If so, an incredible amount of labor has been expended in transporting them to the places which they now occupy,—especially will it appear incredible, when we reflect that all of them were doubtless transported by human hands.

A review of this magnificent monument cannot fail to impress us with admiration of the skill which selected, and the industry which secured this position. Under a military system, such as we feel warranted in ascribing to the people by whom this work was constructed, it must have been impregnable. In every point of view, it is certainly one of the most interesting remains of antiquity which the continent affords.

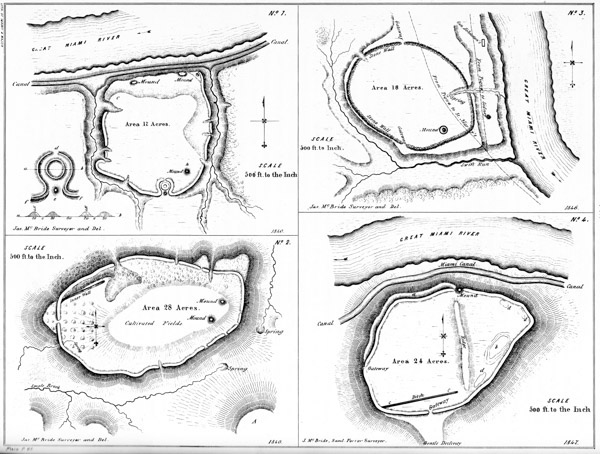

PLATE VIII. No. 1. [From the Surveys and Notes of JAMES MCBRIDE.]

This work occurs on the bank of the Great Miami river, four miles above the town of Hamilton, in Butler county, Ohio, and is one of the most interesting hill-works known. It corresponds in all essential particulars with those of the same class already described. It occupies the summit of a promontory cut from the table lands bordering the Miami river, which upon three sides presents high and steep natural banks, rendered more secure for purposes of defence by artificial embankments thrown up along their brows. The remaining side is defended by a wall and ditch, and it is from this side only that the work is easy of approach. The walls are low, measuring at this time but about four feet in height. The area enclosed is level, subsiding somewhat towards the north, so as to form a sort of natural terrace along the river. Previous to the construction of the Miami canal, this terrace was eight or ten rods wide, having a perpendicular bank next the river, some fifty or more feet high. Upon this terrace are situated several small mounds. The point indicated by c in the plan is the most elevated within the enclosure. The ground here was intermixed with large stones, most of which were removed in building the canal. Among them, it is said, were found several human skeletons, and also a variety of carved stone implements.

The most interesting feature in connection with this work is the entrance on the south, of which the enlarged plan can alone afford a fair conception. The ends p022 of the wall curve inwardly as they approach each other, upon a radius of seventy-five feet, forming a true circle, interrupted only by the gateways. Within the space thus formed, is a small circle one hundred feet in diameter; outside of which and covering the gateway is a mound, e, forty feet in diameter and five feet high. The passage between the mound and the embankment, and between the walls of the circles, is now about six feet wide. The gateway or opening d is twenty feet wide. This singular entrance, it will be remarked, strongly resembles the gateways belonging to a work already described (Plate VI.), although much more regular in its construction.

The ditches, f f, which accompany the wall on the south, subside into the ravines upon either side. These ravines are not far from sixty feet deep, and have precipitous sides, rendering ascent almost impossible. The mound h is three feet high.

The area of the work is seventeen acres; the whole of which is yet covered with a dense primitive forest. The valley beyond the river is broad, and in it are many traces of a remote population, of which this work was probably the fortress or place of last resort, during turbulent periods.

PLATE VIII. No. 2.

This work is situated six miles south-west of the town of Hamilton, in Butler county, Ohio. It has no very remarkable features, although possessing the general characteristics of this class of works. It consists of a simple embankment of earth carried around the brow of a high, detached hill, overlooking a wide and beautiful section of the Miami valley. The side of the hill on the north, towards the river, is very abrupt, and rises to the height of one hundred and twenty feet above the valley. The remaining sides are steep, though comparatively easy of ascent. The walls are scarcely four feet high, and seem to have been much reduced by time. There are six gateways, two of which open upon natural bastions or look-outs, and the remaining four towards copious springs, as shown in the plan. The ground within the walls rises gradually to the centre, from which an extended view of the valley and surrounding country may be obtained. There are two mounds of earth placed near together on the highest point within the enclosure, measuring respectively ten feet in height.

South-east of the work, and nine hundred feet distant, is an eminence A, about fifty feet higher than the one occupied by the above mentioned work,—being much the highest point in the neighborhood. The area on the top is, however, inconsiderable. There are some traces of ancient occupation here, though they are far from being distinct or considerable. p023

PLATE VIII. No. 3.

The enclosure here represented is situated on the left bank of the Great Miami river, two and a half miles above the town of Piqua, Miami county, Ohio, upon the farm of Col. John Johnston, a prominent actor in the early history of Ohio. It occupies the third terrace, which here forms a bluff peninsula, bounded on three sides by streams. The banks of the terrace vary from fifty to seventy-five feet in height. The embankment is carried along the boundaries of the peninsula, enclosing an oval-shaped area of about eighteen acres. It is composed of earth intermixed with large quantities of stone, and is unaccompanied by a ditch. The stones that enter into the composition of the rampart are water-worn, and must have been brought from the bed of the river; which, according to Dr. Drake, for two miles opposite this work, does not at present afford a stone of ten pounds weight. A mound, five feet high and surrounded by a ditch, occurs within the work. There is also another, exterior to the walls, upon the second terrace, towards the river. This is classed as a defensive work, for very obvious reasons.16

Below this entrenchment, and on the present site of the town of Piqua, a group of works formerly existed, consisting of circles, ellipses, etc. These have been described at length, by Major Long.17 There are also various small works on the opposite bank of the Miami. Indeed, the whole valley is here covered with traces of a former dense population.

PLATE VIII. No. 4.18

This work resembles one already described, No. 2 of this Plate. It is situated on the bank of the Great Miami river, three miles below Dayton, Montgomery county, Ohio. The side of the hill towards the river is very steep, rising to the p024 height of one hundred and sixty feet. The remaining sides are less abrupt. Upon the south is the principal gateway, and here the declivity is gentle. This gateway is covered upon the interior by a ditch, c c, twenty feet wide, and seven hundred feet long. At d d d are dug holes, from which it is apparent a portion of the earth composing the embankments was taken. At b is a natural depression forty feet deep, and covering not far from one and a half acres. At the northern slope of the narrow ridge which intersects the work, and within the line of the embankment of which it forms a part, is a small mound. From its top a full view of the surrounding country, for a long distance up and down the river, may be obtained. A terrace, apparently artificial, skirts the north-west side of the hill, thirty feet below the embankment. As remarked in a former instance, this terrace may be natural; it has, however, all the regularity of a work of art.

PLATE IX. No. 1. FORTIFIED HILL, NEAR GRANVILLE, LICKING COUNTY, OHIO.

The work here represented is situated two miles below the town of Granville, Licking county, Ohio. It encloses the summit of a high hill, and embraces an area of not far from eighteen acres. The embankment is, for the most part, carried around the hill at a considerable distance below its brow, and is completely overlooked from every portion of the enclosed area. Unlike all other hill-works which have fallen under notice, the ditch occurs outside of the wall; the earth in the construction of the latter having been thrown upwards and inwards. This is observed equally at the points where the hill is steepest; and the result has been, in the lapse of time, that the ditch is almost obliterated, while the accumulating earth has filled the space above the wall, so that the appearance of the defence, at these points, is that of a high, steep terrace. The height of the wall varies at different places; where the declivity is gentle and the approach easy, it is highest,—perhaps eight or ten feet from the bottom of the ditch; elsewhere it is considerably less. The embankment conforms generally to the shape of the hill. It is interrupted by three gateways, two of which open towards springs of water, and the other, or principal one, upon a long narrow spur, which subsides gradually into the valley of Raccoon creek, affording a comparatively easy ascent.