- ♠

XXXVI.

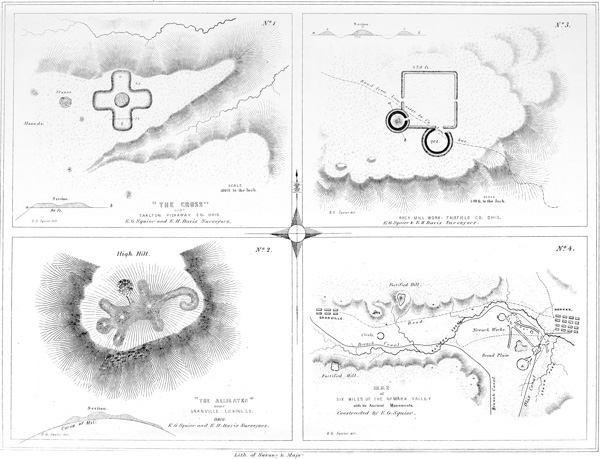

No. 1. “The Cross”, Near Tarlton, Pickaway Co. Ohio.

No. 2. “The Alligator”, Near Granville, Licking Co. Ohio.

No. 3. Rock Mill Work, Fairfield Co. Ohio.

No. 4. Map of Section of Newark Valley.

The headland upon which this effigy occurs is so regular as almost to induce the belief that it has been artificially rounded. Its symmetry has lately been somewhat broken by the opening of a quarry in its face, the further working of which will inevitably result in the entire destruction of this interesting monument.72 It commands a view of the entire valley for eight or ten miles, and is by far the most conspicuous point within that limit. Its prominence is, of necessity, somewhat exaggerated in the small map “exhibiting a section of six miles of the Newark valley,” (No. 4 of the Plate,) in which it is indicated by the letter A. The extensive work E, in the vicinity of Newark, would be distinctly visible from this point, in the absence of the intervening forests. In the valley immediately opposite, and less than half a mile distant, is a large and beautiful circular work, C. To the right, three fourths of a mile distant, is a fortified hill B, (see Plate IX,) and upon the opposing side of the valley is another entrenched hill, D; all of which, together with numerous mounds upon the hill-tops and in the valley, are commanded from this position.

It seems more than probable that this singular effigy, like that last described, had its origin in the superstitions of its makers. It was perhaps the high place where sacrifices were made, on stated or extraordinary occasions, and where the p100 ancient people gathered to celebrate the rites of their unknown worship. Its position, and all the circumstances attending it, certainly favor such a conclusion. The valley which it overlooks abounds in traces of the remote people, and seems to have been one of the centres of ancient population.

PLATE XXXVI. No. 3. ROCK MILL WORKS, FAIRFIELD COUNTY, OHIO.73

This work is remarkable as being the only one, entirely regular in its plan, which has yet been discovered occupying the summit of a hill. It is situated on the road from Lancaster, Fairfield county, Ohio, to Columbus, the capital of the State, seven miles distant from the former place, near a point known as the “Hocking river Upper Falls,” or “Rock Mill.” It consists of a small square measuring four hundred and twenty feet on each side, in combination with two small circles, one hundred and twenty-five and two hundred and ten feet in diameter respectively. The hill is nearly two hundred feet in height, with a slightly undulating plain of small extent at its summit. The works are so arranged that the small circle, enclosing the mound, overlooks every part and commands a wide prospect on every hand. Towards the brow of the hill, at prominent points, are two elliptical terraces or elevations of small size. The sides of the square enclosure correspond to the cardinal points. The walls, excepting those of the circular structures, are very slight, and unaccompanied by a ditch. The work is clearly not of a defensive origin, and must be classed with those of similar outline occupying the river terraces. At a short distance above this point, the champaign country commences, and no other remains are found. The erections of the mound-builders are almost exclusively confined to the borders of the water-courses.

There are very few enclosures, so far as known, in the Hocking river valley; there are, however, numerous mounds upon the narrow terraces and on the hills bordering them. In the vicinity of Athens are a number of the largest size, and also several enclosures. (See Plate XXIII.) Mounds are found upon the high bluffs in the neighborhood of Lancaster, at points commanding the widest range. An examination of the valley with a view of bringing to light its ancient monuments would, without doubt, be attended with very interesting results. p101

PLATE XXXVI. No. 4.

This little map exhibits a section of six miles of the Newark valley, showing the relative positions of the “Newark group” (Plate XXV); the “Fortified Hill” near Granville (Plate IX); and the “Alligator,” just described. But a small proportion of the mounds occurring within this range are shown on the map.

These comprise the only works in the form of animals which have fallen under notice. The singular mound occurring within the great circle near Newark may perhaps deserve to occupy a place with them: that, however, has the internal characteristics of the sacrificial mounds, while the others, so far as our knowledge extends, cover no remains. The mound found within the work in Scioto county, Ohio, (Plate XXIX,) and described on a preceding page, may also rank with them. From the information which we possess concerning the animal effigies of Wisconsin, it does not appear probable that they were constructed for a common purpose with those of Ohio. They occur usually in considerable numbers, in ranges, upon the level prairies; while the few which are found in Ohio occupy elevated and commanding positions,—“high places,” as if designed to be set apart for sacred purposes. An “altar,” if we may so term it, is distinctly to be observed in the oval enclosure connected with the “Great Serpent;” one is equally distinct near the Granville work, and another in connection with the lesser but equally interesting work near Tarlton. If we were to deduce a conclusion from these premises, it would certainly be, that these several effigies possessed a symbolical meaning, and were the objects of superstitious regard.

Whether any other works of this description occur in the State or valley is not known; it is extremely likely, however, that a systematic examination of the whole field would result in the discovery of others equally remarkable, and perhaps disclose a connection between them and the animal effigies of the North-west, already alluded to. The facts that none of these singular remains have been noticed, and that up to this time not a single intimation of their existence has been made public, show how little attention has been bestowed upon our antiquities, and how much remains to be accomplished before we can fully comprehend them.

Such is the character of a large proportion of the ancient monuments of the Mississippi valley. How far a faithful attention to their details has tended to p102 sustain the position assigned them at the commencement of this chapter, the intelligent reader must determine.

The great size of most of the foregoing structures precludes the idea that they were temples in the general acceptation of the term. As has already been intimated, they were probably, like the great circles of England, and the squares of India, Peru, and Mexico, the sacred enclosures, within which were erected the shrines of the gods of the ancient worship and the altars of the ancient religion. They may have embraced consecrated groves, and also, as they did in Mexico, the residences of the ancient priesthood. Like the sacred structures of the country last named, some of them may have been secondarily designed for protection in times of danger; “for,” says Gomara, “the force and strength of every Mexican city is its temple.” However that may be, we know that it has been a practice, common to almost every people in every time, to enclose their temples and altars with walls of various materials, so as to guard the sacred area around them from the desecration of animals or the intrusion of the profane. Spots consecrated by tradition, or rendered remarkable as the scene of some extraordinary event, or by whatever means connected with the superstitions, or invested with the reverence of men, have always been designated in this or some similar manner. The South Sea Islander, as did the ancient Sclavonian, encircles his tabooed or consecrated tree with a fence of woven branches; the pagoda of the Hindoo is enclosed by high and massive walls, within which the scoffer at his religion finds no admittance; the sacred square of the Caaba can only be entered in a posture of humiliation and with unshod feet; and the assurance that “this is holy ground” is impressed upon every one who, at this day, approaches the temples of the true God. The block idol of the poor Laplander has its sacred limit within which the devotee only ventures on bended knees and with face to the earth; the oak-crowned Druid taught the mysteries of his stern religion in temples of unhewn stones, open to the sun, in rude but gigantic structures, which in their form symbolized the God of his adoration; conquerors humbled themselves as they approached the precincts which the voice of the Pythoness had consecrated; no worshipper trod the avenues guarded by the silent, emblematic Sphynx, except with awe and reverence; and Christ indignantly thrust from the sacred area of the temple on Mount Zion the money-changers who had defiled it with their presence. “Thou shalt set bounds to the people round about,—set bounds to the mount and sanctify it,” was the injunction of Jehovah from the holy mountain. Among the savage tribes of North America, none but the pure dared enter the place dedicated to the rude but significant rites of their religion. In Peru none except of the blood of the royal Incas, whose father was the sun, were permitted to pass the walls surrounding the gorgeous temples of their primitive worship; and the imperial Montezuma humbly sought the pardon of his insulted gods for venturing to introduce his unbelieving conqueror within the area consecrated by their shrines.

Analogy would therefore seem to indicate that the structures under consideration, or at least a large portion of them, were nothing more than sacred enclosures. If so, it may be inquired, what has become of the temples and shrines which they p103 enclosed? It is very obvious that, unless composed of stone or other imperishable material, they must long since have completely disappeared, without leaving a trace of their existence. We find nevertheless, within these enclosures, the altars upon which the ancient people performed their sacrifices. We find also pyramidal structures, (as at Portsmouth, Marietta, and other places,) which correspond entirely with those of Mexico and Central America, except that, instead of being composed of stone, they are constructed of earth, and instead of broad flights of steps, have graded avenues and spiral pathways leading to their summits. If these pyramidal structures sustained edifices corresponding to those which crowned the Mexican and Central American Teocalli, they were doubtless, in keeping with the comparative rudeness of their builders, composed of wood; in which case, it would be in vain, at this day, to look for any positive traces of their existence.

-

FOOTNOTES TO CHAPTER III.

-

36 “I have reason to agree with Stukely, that the circumstance of the ditch being within the vallum is a distinguishing mark between religious and military works.”—Sir R. C. Hoare on the Monuments of England.

-

38 This work is marked D in the Map, Plate II. Since this Plate was engraved, it has been ascertained that a plan of this work was published in the “Portfolio,” in 1809. The two plans are substantially alike, except that the one in the “Portfolio” represents the parallels as terminating in a small circle, and as connected with the large circle,—both of which features are erroneous. The walls of the parallels are much obliterated, where they approach the bank of the terrace.

-

40 These works are marked E and F respectively, in Map, Plate II.

-

42 To put, at once, all skepticism at rest, which might otherwise arise as to the regularity of these works, it should be stated that they were all carefully surveyed by the authors in person. Of course, no difficulty existed in determining the perfect regularity of the squares. The method of procedure, in respect to the circles, was as follows. Flags were raised at regular and convenient intervals, upon the embankments, representing stations. The compass was then placed alternately at these stations, and the bearing of the flag next beyond ascertained. If the angles thus determined proved to be coincident, the regularity of the work was placed beyond doubt. The supplementary plan A indicates the method of survey, the “Field Book” of which, the circle being thirty-six hundred feet in circumference, and the stations three hundred feet apart, is as follows:—

STATION.BEARING.DISTANCE.1N. 75° E.300 feet.2N. 45° E.300 feet.3N. 15° E.300 feet.4N. 15° W.300 feet.5N. 45° W.300 feet.6N. 75° W.300 feet.7S. 75° W.300 feet.8S. 45° W.300 feet.9S. 15° W.300 feet.10S. 15° E.300 feet.11S. 45° E.300 feet.12S. 75° E.300 feet. -

43 Indicated by the letter B, in Map 1, Plate III. This and the succeeding work are represented by Mr. Atwater in the Archæologia Americana, vol. i. p. 146; with what fidelity, an inspection of the respective plans will show.

-

45 Mr. Atwater (Archæologia Americana, vol. i. p. 143) describes the small mound at e, as composed “entirely of red ochre, which answers very well as a paint!” Its present composition is a clayey loam. It has been examined and found to contain an altar.

-

46 This work is designated by the letter H on the Map, already several times referred to, Plate II.

-

48 The site of the town of Frankfort was formerly that of a famous Shawnee town. The burial place of the Indian town is shown in the plan; from it numerous relics are obtained,—gun-barrels, copper kettles, silver crosses and brooches, and many other implements and ornaments which, in accordance with aboriginal custom, were buried with the dead. Some of them, from being found in close proximity to the work above described, have erroneously been supposed to appertain to the race of the mound-builders.

-

49 Archæologia Americana, vol. i. p. 142.

-

52 The proportions of the circles, etc., are necessarily somewhat exaggerated in the plan: their relative positions are, however, very accurately preserved.

-

53 There are some singular structures in Sweden, which coincide very nearly with this remarkable little work. They are circles composed of upright stones, having short avenues of approach upon each side, opposite each other, in the manner here represented. See Sjöborg’s Samlingar för Nordens Fornälskare, 1822.

-

54 A number of plans of these works, as well as of those at Marietta, have been published; but they are all very defective, and fail to convey an accurate conception of the group. The map here given is from an original and very careful and minute survey made in 1836, by CHAS. WHITTLESEY, Esq., Topographical Engineer of the State of Ohio, corrected and verified by careful re-surveys and admeasurements by the authors. It may be relied upon as strictly correct. A large portion of the more complicated division of the group has, within the past few years, been almost completely demolished, so that the lines can no longer be satisfactorily traced. It is to be hoped that care may be taken to preserve the remainder from a like fate. The principal structures will always resist the reducing action of the plough: but, from present indications, the connecting lines and smaller works will soon be levelled to the surface, and leave but a scanty and doubtful trace of their former symmetry.

A sectional map of the Newark valley is given in a subsequent plate, on which the relative positions of this and other works of the vicinity are indicated with approximate accuracy.

-

55 “Great as some of these works are, and laborious as was their construction, particularly those of Circleville and Newark, I am persuaded they were never intended for military defences.”—General Harrison’s Discourse.

-

56 The following passages, embodying some interesting facts respecting these works, were communicated by I. DILLE, Esq., now and for many years a resident of Newark:

“You are aware that the principal part of these remains are situated in the valley between the Raccoon creek and the South fork of Licking creek. The valley is here nearly two miles wide, from stream to stream. To the east of the lines of embankment and on the second bottom of the creek are numerous mounds. Some of these are very low,—so low, indeed, that a careless observer would hardly distinguish them from the common surface. Some of them are surrounded by a low circular wall of earth which, with a little attention, can be distinctly traced. In the year 1828, when constructing the canal, a lock was located on the site of one of these low mounds. In excavating the lock pit, fourteen human skeletons were found about four feet beneath the surface. These were very much decayed, and supposed by some to have been burnt. It was probably the natural appearance of decomposition which led to this opinion. On coming to the air they all mouldered into dust. Over these skeletons, and carefully and regularly disposed, was laid a large quantity of mica in sheets or plates. Some of these were eight and ten inches long by four and five wide, and all from half an inch to an inch thick. It was estimated that fifteen or twenty bushels of this material were thrown out to form the walls or supports of the lock. From a mound some four feet high, a few rods to the south of this, a large volvaria (sea-shell) was taken.

“On the opposite side of the creek I found, in one place, twenty-four flint axes, or imperfect arrow-heads. These were found on the third bottom, on a promontory projecting towards the works in question. A very great quantity of broken flints were found here—enough to load a cart. They were of the same variety of flint, chert, or hornstone, which abounds on ‘Flint Ridge.’ On that ridge there is the appearance of a great deal of digging. Deep holes cover the ground for the extent of a mile. Many have supposed that these were mines of the precious metals, and no small amount of money and time has been expended in the search. I am of the opinion this place is the source of all the arrow-heads, flint axes, and other implements of that material, which have been used over a wide extent of territory.

“Separate from these valley works, and two miles to the west of them, is an irregular enclosure on a hill. The walls are of earth about three feet high, and enclose an area of some thirty or forty acres, extending from the top to the very foot of a high, long, and sloping hill. Again, two miles distant in a north-west direction, the summit of a high hill is surrounded by a similar embankment.”

-

57 The map here presented is drawn from a careful survey of these works, made in 1837, by CHARLES WHITTLESEY, Esq., Topographical Engineer of the State, under the law authorizing a Geological and Topographical Survey of Ohio. It has never before been published; and its fidelity, in every respect, may be relied on. It will be seen that the supplementary or “small covert way” represented on the plan in the Archæologia Americana, does not appear. What was taken for a graded way is simply a gully, worn by the rains. The topography of the map, and the accompanying sections, are features which every intelligent inquirer will know how to appreciate.

-

58 The description of the two principal truncated pyramids embodies the substance of an account of the same, published by Dr. S. P. HILDRETH of Marietta, in the “American Pioneer” for June, 1843,—the entire fidelity of which has been attested by actual survey.

-

59 Such is the result of careful admeasurements made by Dr. JOHN LOCKE, whose accuracy in matters of this kind, as in all others, is worthy of emulation.

-

60 A very laudable disposition has been manifested, on the part of the citizens of Marietta, to preserve the interesting remains in their midst. The Directors of the Ohio Land Company, when they took possession of the country at the mouth of the Muskingum, in 1788, adopted immediate measures for the preservation of these monuments. To their credit be it said, one of their earliest official acts was the passage of a resolution, which is entered upon the journal of their proceedings, reserving the two truncated pyramids and the great mound, with a few acres attached to each, as public squares. They placed them under the care of the future corporation of Marietta, directing that they should be embellished with shade trees, when divested of the forest which then covered them, which trees, it was added, should be of native growth, and of the varieties named in the resolution. The great mound with its surrounding square was designated as a cemetery, and placed under the control of trustees. Ten years ago, these structures being yet unenclosed and much injured by the rains washing through the paths caused by the cattle that roamed over them, the citizens raised a sum of money adequate to the purpose, and fully restored them. The magnificent avenue named, not inappropriately, by the Directors, “Sacra Via,” or Sacred Way, but now generally known as the “Covered Way,” was also preserved by a special resolution of the Company, “never to be disturbed or defaced, as common ground, not to be enclosed.” One of the streets of Marietta, Warren street, passes through this avenue. It is, of course, impossible to resist encroachments upon the walls of the enclosures, which are rapidly disappearing.

Had a similar enlightened policy marked the proceedings of all the early companies and settlers of the West, we should not now have occasion to regret the entire obliteration of many interesting remains of antiquity. Or did a similar disposition exist generally, there would be less necessity for a careful, systematic, and immediate survey of our remaining monuments. The works at Chillicothe, Circleville, Cincinnati, and St. Louis, might have been preserved with all ease: and would have constituted striking ornaments to those cities, to say nothing of the interest which would attach to them in other points of view. It is proper to observe, that the facts embraced in this note were kindly communicated by Dr. S. P. HILDRETH, of Marietta.

-

61 The account of an English adventurer named Ashe, respecting some extraordinary remains which he professed to have discovered here, it is hardly necessary to say, is entitled to no credit whatever. The remark holds good of similar accounts, by the same hand, of some of the works at Newark, one hundred miles above, on the upper tributaries of the Muskingum.

-

62 From the Survey and Notes of JAMES MCBRIDE, Esq.

-

63 From the Survey and Notes of CHARLES WHITTLESEY, Esq.

-

64 From the Plan and Notes of CHARLES WHITTLESEY, Esq.

-

65 From the Survey and Notes of JAMES MCBRIDE Esq.

-

66 From the Survey and Notes of JAMES MCBRIDE Esq.

-

67 “It consists of a ditch dug down to the edge of the river, the earth from which has been thrown up principally upon the lower or down river side. The breadth between the parapets is much greater near the water than at any other point, so that it might have been used for the purpose of affording a safe passage to the river or as a sort of harbor in which canoes may have been drawn up or both. This water way resembles that found at Marietta though smaller.”—Long’s Second Expedition, vol. i. p. 60.

-

68 The reader is requested to compare the plan of this work given by Mr. ATWATER in the Archæologia Americana, with the one here presented.

-

69 Previous to the entire destruction of this mound, and at the time when about one half of it remained, it was examined by Mr. McBride, from whose original notes the following observations respecting it are taken:

“The mound was composed of rich surface mould, evidently scooped up from the surface; scattered through which were pebbles and some stones of considerable size, all of which had been burned. Upon excavation, we found a skeleton with its head to the east, resting upon the original surface of the ground, immediately under the apex of the mound. Some distance above this was a layer of ashes of considerable extent, and about four inches thick. The skeleton was of ordinary size; the skull was crushed, and all the bones in extreme decay. Near the surface were other skeletons. The inhabitants of the neighborhood tell of a copper band with strange devices, found around the brow of a skeleton in this mound; and also of a well carved representation of a tortoise of the same metal, twelve or fourteen inches in length, found with another skeleton.”

-

70 From the Rafinesque MSS.

-

71 From the Survey of JAMES MCBRIDE.

-

72 The proprietor of this structure, ASHEL AYLESWORTH, Esq., we are happy to say, has determined to permit no further encroachment upon it. It is to be hoped that the citizens of Granville will adopt means to permanently and effectually secure it from invasion.

-

73 This work should have been figured on a preceding plate. Its position, in connection with the effigies here described, was determined by accidental circumstances.

-