The sculpture of these articles, which is sometimes attempted in imitation of the human figure and of various animals, is often tasteful. But they never display the nice observation, and true, artistic appreciation and skill exhibited by those of the mounds, notwithstanding their makers have all the advantages resulting from steel implements for carving, and from the suggestions afforded by European art. The only fair test of the relative degrees of skill possessed by the two races would be in a comparison of the remains of the mounds with the productions of the Indians before the commencement of European intercourse. A comparison with the works of the latter however, at any period, would not fail to exhibit in a striking light the greatly superior skill of the ancient people.

-

FOOTNOTES TO CHAPTER XIII.

-

133 The Spaniards entertained a strong dread of these weapons. Their historians tell some wonderful stories of their

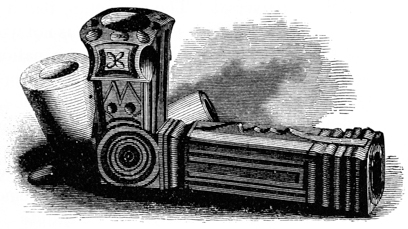

Fig. 101.

Fig. 102.

Fig. 101.

Fig. 102.

efficiency, and affirm that one stroke was sufficient to cut a man

through the middle or decapitate a horse. The form of this sword,

which was called mahquahuitl

by the Mexicans, is represented in the

accompanying engraving (Fig. 101).

efficiency, and affirm that one stroke was sufficient to cut a man

through the middle or decapitate a horse. The form of this sword,

which was called mahquahuitl

by the Mexicans, is represented in the

accompanying engraving (Fig. 101).The Pacific islanders possess similar weapons, formed by inserting rows of shark’s teeth on the opposite sides of a staff or sword shaped piece of tough wood, and fastening the same with cords of native grass. One of this kind from the Aleutian Islands is here engraved (Fig. 102).

-

134 Lawson, in his account of the Carolina Indians, published in 1709, mentions having seen at an Indian town “very long arrows, headed with pieces of glass, which they had broken from bottles. They were shaped neatly, like the head of a dart, but the way they did it I can’t tell” (p. 58). It is probable that these arrows were pointed with obsidian or quartz, which would be very liable to be mistaken for glass. Fremont (Second Expedition, p. 267) observed some Indians, of unusually fearless character, on the Rio de los Angelos of Upper California, who possessed arrows “barbed with a very clear, translucent stone, a species of opal, nearly as hard as a diamond.”

-

135 Wilkinson’s Egypt, vol. iii. p. 261.

-

136 Clarke’s Travels, vol. iii p. 22.

-

137 LOSKIEL says of the axes of the Delaware Indians: “Their hatchets are wedges, made of hard stones, six or seven inches long, sharpened at the edge, and attached to a wooden handle. They are not used to fell trees, but only to peel them, and kill their enemies” (p. 54). ADAIR, speaking of the Southern tribes, observes: “They twisted two or three hickory slips, about two feet long, around the notched head of the axe, and by means of this simple and obvious invention they deadened the trees, by cutting through the bark, and burned them when they became thoroughly dry” (p. 405).

-

138 Presented by JOHN HALL, Esq., New York. Nos. 1 and 2 are in the cabinet of JAMES MCBRIDE, Esq.

-

139 In the cabinets of B. L. C. WAILES, Esq., Washington, Miss.; and of Rev R. MORRIS, Mount Sylvan, in the same State.

-

140 In the cabinet of JAMES MCBRIDE, Hamilton, Ohio.

-

141 In the cabinet of ERASMUS GEST, Esq., and drawn by H. C. GROSVENOR of Cincinnati.

-

142 “The needles and thread they used formerly (and now at times) were fish bones, or the horns or bones of deer rubbed sharp, and deer’s sinews, and a sort of hemp that grows, among them spontaneously.”—Adair’s American Indians, p. 6.

Mr. Stevens found a similar implement with the skeleton, in one of the ancient tombs near Ticul in Yucatan. “It was made of deer’s horn, about two inches long, sharp at the point, with an eye at the other end. The Indians of the vicinity still use needles of the same material.”—Travels in Yucatan, vol. i. p. 279.

-

143 Rev. J. B. Finley (distinguished for his zealous efforts in christianizing the Indian tribes of Ohio) states that, among the tribes with which he was acquainted, stones identical with those above described were much used in a popular game resembling the modern game of “ten pins.” The form of the stones suggests the manner in which they were held and thrown, or rather rolled. The concave sides received the thumb and second finger, the forefinger clasping the periphery. Adair, in his notice of the Southern Indians, gives a minute and graphic account of a game somewhat analogous to that described by Mr. Finley, in which stones of this description were used. Du Pratz notices the same game, and fully explains the purpose of the oblique-edged stones, Nos. 4 and 6 of the text. These, when rolled, would describe a convolute figure. The lines on the stones, resembling bird-tracks, were probably in some way connected with “counting” the game.

“The warriors have another favorite game, called Chungke; which, with propriety of language, may be called ‘running hard labor.’ They have near their state house a square piece of ground well cleaned; and fine sand is strewed over it, when requisite, to promote a swifter motion to what they throw along its surface. Only one or two on a side play at this ancient game. They have a stone about two fingers broad at the edge and two spans round; each party has a pole about eight feet long, smooth and tapering at each end, the points flat. They set off abreast of each other, at six yards from the edge of the playground; then one of them hurls the stone on its edge, in as direct a line as he can, a considerable distance towards the middle of the other end of the square; when they have run a few yards, each darts his pole, anointed with bear’s grease, with a proper force, as near as he can guess, in proportion to the motion of the stone, that the end may lie close to the same;—when this is the case the person counts two of the game, and in proportion to the nearness of the poles to the mark, one is counted, unless by measurement both are found to be an equal distance from the stone. In this manner the players will keep moving most of the day at half speed, under the violent heat of the sun, staking their silver ornaments; their nose, finger, and ear rings; their breast, arm, and wrist plates; and all their wearing apparel, except that which barely covers their middle. All the American Indians are much addicted to this game, which appears to be a task of stupid drudgery; it seems, however, to be of early origin, when their forefathers used diversions as simple as their manners. (The hurling stones they use at present were, from time immemorial, rubbed smooth on the rocks, and with prodigious labor; they are kept with the strictest religious care from one generation to another, and are exempt from being buried with the dead.) They belong to the town where they are used, and are carefully preserved.”—Adair’s History of American Indians, p. 402.

“The warriors practise a diversion which they call the game of the pole, at which only two play at a time. Each pole is about eight feet long, resembling a Roman f, and the game consists in rolling a flat round stone, about three inches in diameter and one inch thick, with the edges somewhat sloping, and throwing the pole in such a manner that when the stone rests, the pole may be at or near it. Both antagonists throw their pole at the same time, and he whose pole is nearest the stone counts one, and has the right of rolling the stone.”—Du Pratz, History of Louisiana, 1720, p. 366.

Mr. Breckenridge (Views of Louisiana, p. 256) mentions a game popular among the Arikara, (Riccarees,) played with a ring of stone. Lewis and Clarke also mention a game common among the Mandans, similar to the one above described, and which was also played with rings of stone. Mr. Catlin, (vol. i. p. 132) both describes and illustrates the game, which, among the Mandans as well as among the Creeks, was denominated “Tchung-kee.”

Discoidal stones analogous, if not identical, with these, have been found in abundance in Chili. “In the plains and upon the mountains,” says Molina, “are to be seen a great number of flat circular stones, of five or six inches in diameter, with a hole through the middle. These stones, which are either granite or porphyry, have doubtless received this form by artificial means, and I am induced to believe that they were the clubs or maces of the ancient Chilians, and that the holes were perforated to receive the handles.”—Molina, vol i. p. 56.

-

144 In the possession of J. VAN CLEVE, Esq., of Dayton, Ohio.

-

145 In the cabinet of Dr. S. P. HILDRETH, Marietta, Ohio.

-

146 Several tubes, of very much the same character with those here referred to, have been found in the vicinity of the Grave creek mound. Mr. SCHOOLCRAFT describes them as made out of a compact, blue and white mottled steatite, measuring from eight to twelve inches in length, by one inch and four tenths in diameter, and having a bore of four fifths of an inch, diminishing at one end to one fifth of an inch. Our author observes:

“By placing the eye at the diminished point, the extraneous light is shut from the pupil, and distant objects more clearly discerned. The effect is telescopic, and is the same which is known to be produced by directing the sight towards the heavens from the bottom of a well,—an object which we now understand to have been secured by the Aztec and Maya races in their astronomical observations, by constructing tubular chambers. The quality of the stone, like most of the magnesian species, is soft enough to be cut with a knife. It is evident that the circular lines observed in the calibre were produced by boring. The circular striæ of this process are plainly apparent. I learned by inquiry, that a quarry or locality of this species of rock exists on the banks of Grave creek, some four or five miles above the mound. This establishes the fact, that they were made here and not brought from a distance. The degree of skill evinced by these curious instruments is superior to that observed in the pipe-carvings and other evidences of North American Indian sculpture.”—Observations on the Grave creek Mound, Transactions of American Ethnological Society, vol. i. p. 406.

-

147 According to Vanegas, the “medicine men” of the Californian tribes of Indians, in their operations for the cure of diseases, sometimes used tubes of stone. The operation in which they were used, was a kind of cautery.

“One mode was very remarkable, and the good effect it sometimes produced heightened the reputation of the physician. They applied to the suffering part of the patient’s body the chacuaco, a tube formed out of a very hard black stone; and through this they sometimes sucked and at other times blew, but both as hard as they were able, supposing that the disease was either exhaled or dispersed. Sometimes the tube was filled with cimarron or wild tobacco lighted, and here they either sucked in or blew down the smoke, according to the physician’s directions, and this powerful caustic sometimes, without any other remedy, has been known entirely to remove the disorder.”—Vanegas’ California, vol. i. p. 97.

-