BATIK IN HOLLAND

Batik in America is still a comparatively recent importation; brought here some ten years ago, it was met with absolute incomprehension and lack of interest, but its real merit as a means of decorating fabrics has earned it a place in the industrial art of the nation and year by year it is gaining wider recognition.

For two hundred and seventy odd years it has been known in Holland, to which country it was brought by the Dutch traders from Java in the middle of the seventeenth century. It was not, however, received very enthusiastically and the commercial failure that followed the importation of some 2000 pieces (which were finally sold at auction, as no market could be found for them through regular channels) did not encourage traders in their efforts to popularize batiks. From that time, that is, about 1750 until 1817, interest in the work decidedly flagged and the honour of reviving it must be given primarily to Raffles who gave a description of it in his well known “History of Java” published at the latter date. He, however, seems to have had very little personal feeling for the art and merely wrote it up as a matter of history, and it remained for the modern artists to give it is first real impetus.

The present keen interest in the craft is mainly due to Chris Lebeau, Dijesselhof and Lion Cachet, who have, by their wonderful work, revived and stimulated a nation-wide appreciation of the art.

American batik has recently gone through a phase of development similar to that experienced in Holland some twelve years ago. It has been in danger of getting into the class of transient “cults” and becoming a fashionable pastime with a rise and fall similar to the craze for doing peasant wood-carving, burnt-wood work or sweater knitting. But here, too, its real merit has saved it from becoming just a modish amusement. In Holland it was even introduced into girls’ schools as a regular course, so that graduates might enter the social world fully equipped! Luckily for its ultimate survival, however, it required so much technical knowledge that it was soon left to serious students, but the desire for the beautiful results obtained by the process was not relinquished so willingly and the result was that people tried to produce the effect without the work. This imitation was called a “secret process” and enjoyed considerable vogue.

The general public believed that this substitute was real batik, because the material had been dipped and some wax had been used, but any one who knew anything about the genuine process, was not fooled and recognized that stencils and various other fake methods had been utilized. The unlimited patience of the native worker was unknown, and unsung was the thoroughness of the painstaking craftsman. At this period the watch-word was “speed” and the results showed it.

The importance placed on the “crackle effect” is another parallel in the phases of development in Holland and America. Crackle certainly has its place in the beauty of batik, but the indiscriminate use of it as a complete motive of decoration in itself, is to be regretted. It would be used less, probably, if examples of the best native and European work were studied, in which real design and colour are the arresting features.

Even whilst admitting that the medium does limit the designer to a certain extent, study of the work of the before-mentioned Dutchmen, Dijesselhof and Lebeau, will show the variety of design, feeling and temperament that can be expressed through the batik process.

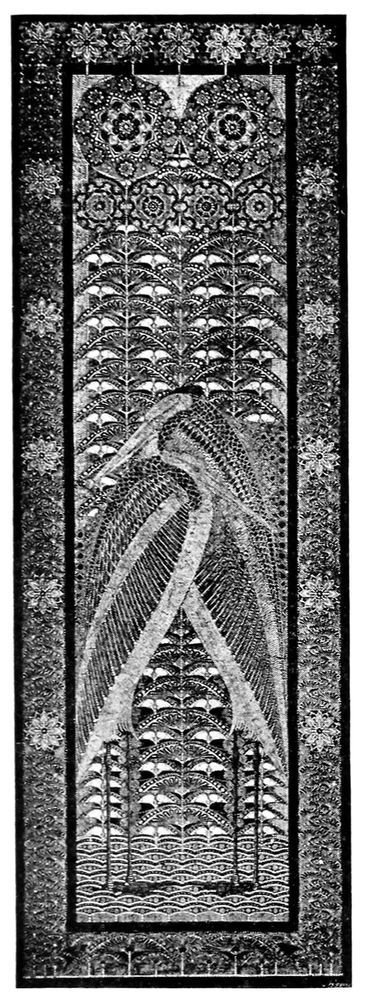

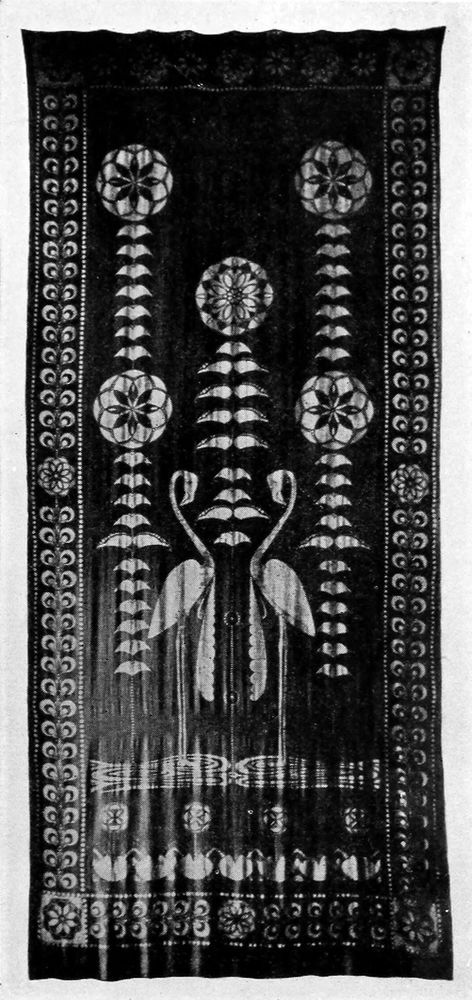

Dijesselhof considers batik a better way to express himself for his mural decorations than either oil or water colour painting. He uses the brush to a great extent and works with great freedom of execution, making the medium conform to his own particular type of work. Lebeau, on the other hand, after the manner of the Javanese, sees the tjanting as the only tool with which to produce his richly fantastic designs. Lebeau is technically the greater artist and possesses a supreme disregard of time when he is producing a magnificently ornamented textile; his attitude toward his work is reminiscent of that of the monks who in bygone ages, spent years on the intricate and beautiful ornamentation of their laboriously hand-lettered books of devotion. They, too, had perfection of design and craftsmanship as their only standard.

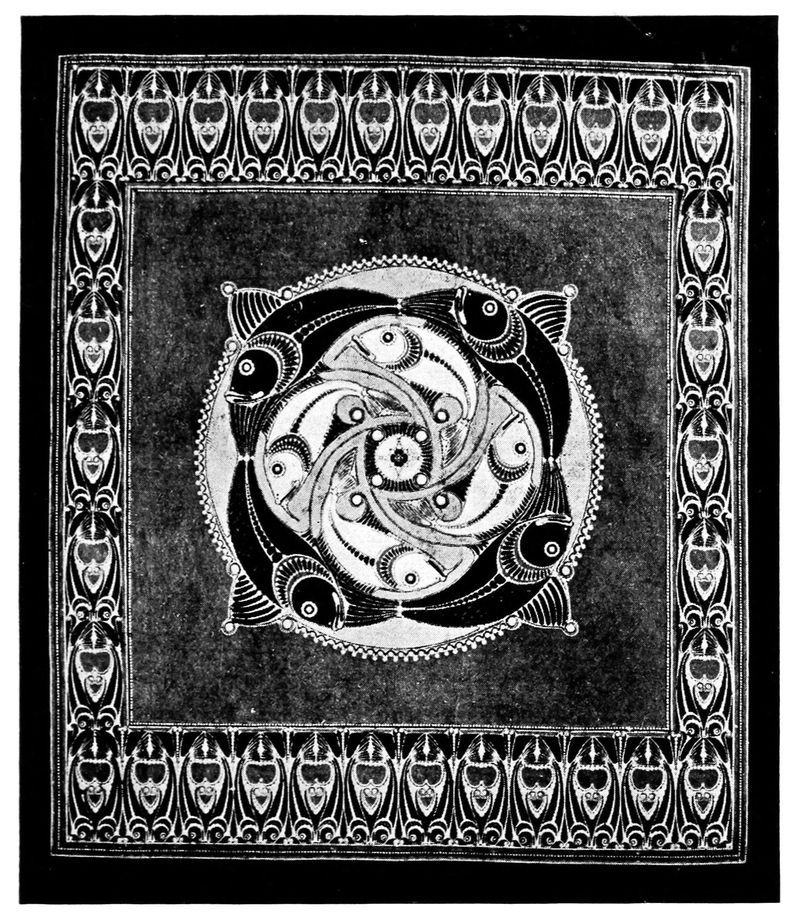

These men have been an inspiration to Dutch artists, and the illustration of a batik by Chris Lebeau facing page 26 will give the reader a good idea of the high standard of proficiency this Dutch artist and craftsman has achieved. It will be seen that no actual lines were used in these designs; if a line effect was wanted it was made by a series of little round dots, almost equal in size, with the result that a soft pleasing line is obtained instead of a hard one.

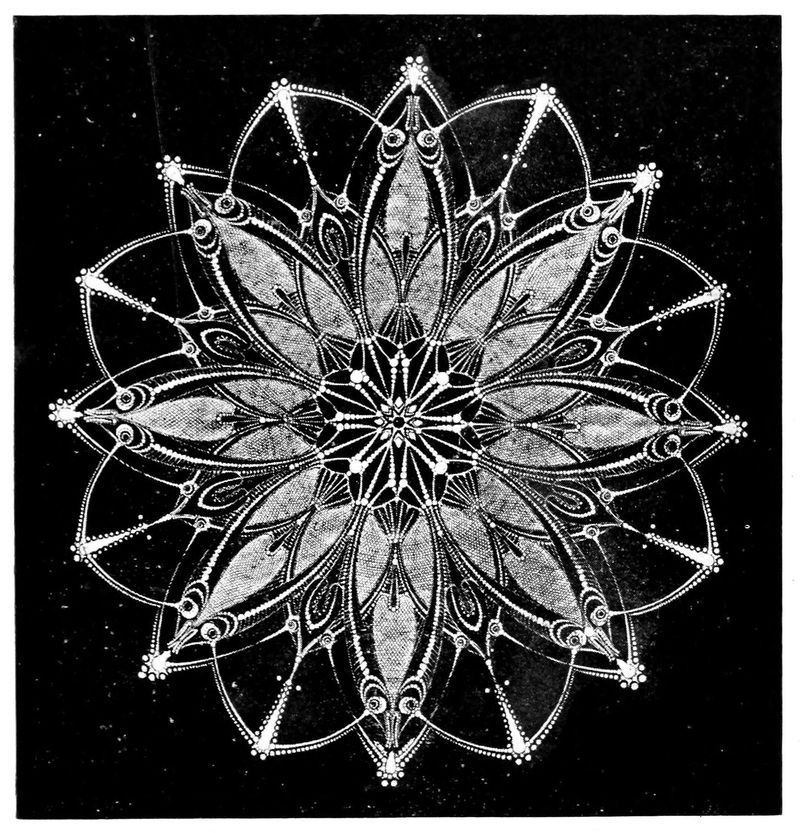

By graduating the size of the dots, from small to large, an effect is produced that never could be obtained with lines; not only are the lines treated in this way, but whole surfaces in which a light tone is desired, instead of being “covered off” with a brush, are laid in with countless dots very close together. As can be readily understood this hand-work requires the acme of craftsmanship, for if the dots are placed irregularly, that is to say, if their arrangement is not directly harmonious with the main lines of the design, the pattern formed by the spaces between them, would disturb the rest of the drawing.

In the second reproduction it can be seen that the little dots are actually laid in circles, but with such regularity that no circles are shown. The workmanship in the stork design is even more amazing than that of the two first decorations and it is hard to believe that a human being has had sufficient patience to execute such a design.

In Europe, batiks are chiefly used for interior decoration; table covers, screens and lamp-shades being more popular than costumes decorated by the process. It is also used to a certain extent in book-binding, on paper and on parchment. Practically the same methods are employed when batiking these materials as for woven goods, but experimenters are advised to take the greatest care when handling paper, which of course, when wet, tears very easily.

To batik parchment it is necessary to first soak it, in order to make it pliable, then whilst wet, it should be stretched on a piece of plate glass, slightly larger than the parchment, and glued at the edges with strips of paper binding. When thoroughly dry the design is pounced on or drawn in with pencil. Before starting to apply the wax the glass must be warmed from the back, in order to make certain of an easy flowing of the wax; if the parchment is cold it will be found that the wax congeals too quickly and will not be workable. The parts of the design to be left un-coloured are covered with wax as usual, and a little wall of clay is built around the edge of the glass; this forms a bath into which the dye is poured. The colour is allowed to soak in thoroughly and the dye is then poured off, the process being repeated if the tone from the first bath is not intense enough; other colours are applied in the same way. The wax is then removed by sponging carefully with gasoline.

Aniline dyes are used chiefly and occasionally acids which produce colour by their action on each other, are employed. Vegetable dyes are popular in Holland on account of their permanence, the Dutch being almost as particular about the durability of their work as the Javanese. This is natural when one remembers that, there, the batik art is considered in the same light as painting and sculpture, and frequent exhibitions are held for a public whose attitude toward the craft is very different to that of many Americans, who do not yet appreciate the art as an art.

Beside public interest, the government of Holland has done its best to stimulate the study of the craft. Experimenting stations are maintained, where free of all cost, the artist can have his batiked design dyed and he is given all the information and help that he wants. This, of course, means a great deal to the beginner who knows little or no chemistry, some knowledge of which is quite essential to one who would become a really expert dyer.