Chapter XIII.

Barbaric Aristocracy.

Jacob, the ‘Impostor’—The Barterer—Esau, the ‘Warrior’—Barbarian Dukes—Trade and War—Reconciliation of Jacob and Esau—Their Ghosts—Legend of Iblis—Pagan Warriors of Europe—Russian Hierarchy of Hell.

In the preceding chapter it was noted that there were two myths wrapped up in the story of Jacob and Esau,—the one theological, the other human. The former was there treated, the latter may be considered here. Rabbinical theology has made the Jewish race adopt as their founder that tricky patriarch whom Shylock adopted as his model; but any censure on them for that comes with little grace from christians who believe that they are still enjoying a covenant which Jacob’s extortions and treacheries were the divinely-adopted means of confirming. It is high time that the Jewish people should repudiate Jacob’s proceedings, and if they do not give him his first name (‘Impostor’) back again, at least withdraw from him the name Israel. But it is still more important for mankind to study the phases of their civilisation, and not attribute to any particular race the spirit of a legend which represents an epoch of social development throughout the world.

When Rebekah asked Jehovah why her unborn babes struggled in her womb, he answered, ‘Two nations are in thy womb. One people shall be stronger than the other people; the elder shall be subject to the younger.’ What peoples these were is described in the blessings of Jacob on the two representatives when they had grown up to be, the one red and hairy, a huntsman; the other a quiet man, dwelling in tents and builder of cattle-booths.

Jacob—cunning, extortionate, fraudulent in spirit even when technically fair—is not a pleasing figure in the eyes of the nineteenth century. But he does not belong to the nineteenth century. His contest was with Esau. The very names of them belong to mythology; they are not individual men; they are conflicting tendencies and interests of a primitive period. They must be thought of as Israel and Edom historically; morally, as the Barter principle and the Bandit principle.

High things begin low. Astronomy began as Astrology; and when Trade began there must have been even more trickery about it than there is now. Conceive of a world made up of nomadic tribes engaged in perpetual warfare. It is a commerce of killing. If a tribe desires the richer soil or larger possessions of another, the method is to exterminate that other. But at last there rises a tribe either too weak or too peaceful to exterminate, and it proposes to barter. It challenges its neighbours to a contest of wits. They try to get the advantage of each other in bargains; they haggle and cheat; and it is not heroic at all, but it is the beginning of commerce and peace.

But the Dukes of Edom as they are called will not enter into this compact. They have not been used to it; they are always outwitted at a bargain; just like those other red men in the West of America, whose lands are bought with beads, and their territorial birthright taken for a mess of pottage. They prefer to live by the hunt and by the sword. Then between these two peoples is an eternal feud, with an occasional truce, or, in biblical phrase, ‘reconciliation.’

Surrounded by a commercial civilisation, with its prosaic virtues and its petty vices, we cannot help admiring much about the Duke of Edom, non-producer though he be. Brave, impulsive, quick to forgive as to resent; generous, as people can afford to be when they may give what they never earned; his gallant qualities cast a certain meanness over his grasping brother, the Israelite. It is a healthy sign in youth to admire such qualities. The boy who delights in Robin Hood; the youth who feels a stir of enthusiasm when he reads Schiller’s Robbers; the ennuyés of the clubs and the roughs, with unfulfilled capacities for adventure in them, who admire ‘the gallant Turk,’ are all lingering in the nomadic age. They do not think of things but of persons. They are impressed by the barbaric dash. The splendour of warriors hides trampled and decimated peasantries; their courage can gild atrocities. Beside such captivating qualities and thrilling scenes how poor and commonplace appear thrifty rusticity, and the cautious, selfish, money-making tradesmen!

But fine and heroic as the Duke of Edom may appear in the distance, it is best to keep him at a distance. When Robin Hood reappeared on Blackheath lately, his warmest admirers were satisfied to hear he was securely lodged in gaol. The Jews had just the same sensations about the Dukes of Edom. They saw that tribe near to, and lived in daily dread of them. They were hirsute barbarians, dwelling amid mountain fastnesses, and lording it over a vast territory. The weak tribe of the plains had no sooner got together some herds and a little money, than those dashing Edomites fell upon them and carried away their savings and substance in a day. This made the bartering tribe all the more dependent on their cunning. They had to match their wits against, the world; and they have had to do the same to this day, when it is a chief element of their survival that their thrift is of importance to the business and finance of Europe. But in the myth it is shown that Trade, timorous as it is in presence of the sword, may have a magnanimity of its own. The Supplanter of Edom is haunted by the wrong he has done his elder brother, and driven him to greater animosity. He resolves to seek him, offer him gifts, and crave reconciliation. It is easy to put an unfavourable construction upon his action, but it is not necessary. The Supplanter, with droves of cattle, a large portion of his possessions, passes out towards perilous Edom, unarmed, undefended, except by his amicable intentions towards the powerful chieftain he had wronged. At the border of the hostile kingdom he learns that the chieftain is coming to meet him with four hundred men. He is now seized, with a mighty spirit of Fear. He sends on the herdsmen with the herds, and remains alone. During the watches of the night there closes upon him this phantom of Fear, with its presage of Death. The tricky tradesman has met his Conscience, and it is girt about with Terror. But he feels that his nobler self is with it, and that he will win. Finely has Charles Wesley told the story in his hymn:—

Come, O thou traveller unknown,

Whom still I hold but cannot see!

My company before is gone

And I am left alone with thee:

With thee all night I mean to stay

And wrestle till the break of day.

‘Confident in self-despair,’ the Supplanter conquers his Fear; with the dawn he travels onward alone to meet the man he had outraged and his armed men, and to him says, ‘I have appeared before thee as though I had appeared before God, that thou mightest be favourable to me.’ The proud Duke is disarmed. The brothers embrace and weep together. The chieftain declines the presents, and is only induced to accept them as proof of his forgiveness. The Tradesman learns for all time that his mere cleverness may bring a demon to his side in the night, and that he never made so good a bargain as when he has restored ill-gotten gains. The aristocrat and warrior returns to his mountain, aware now that magnanimity and courage are not impossible to quiet men living by merchandise. The hunting-ground must make way now for the cattle-breeder. The sword must yield before the balances.

Whatever may have been the tribes which in primitive times had these encounters, and taught each other this lesson, they were long since reconciled. But the ghosts of Israel and Edom, of Barter and Plunder, fought on through long tribal histories. Israel represented by the archangel Michael, and Edom by dragon Samaël, waged their war. One characteristic of the opposing power has been already considered. Samaël embodied Edom as the genius of Strife. He was the especial Accuser of Israel, their Antichrist, so to say, as Michael was their Advocate. But the name ‘Edom’ itself was retained as a kind of personification of the barbaric military and lordly Devil. The highwayman in epaulettes, the heroic spoiler, with his hairy hand which Israel itself had imitated many a time in its gloves, were summed up as ‘Edom.’

This personification is the more important since it has characterised the more serious idea of Satan which prevails in the world. He is mainly a moral conception, and means the pride and pomp of the world, its natural wildness and ferocities, and the glory of them. The Mussulman fable relates that when Allah created man, and placed him in a garden, he called all the angels to worship this crowning work of his hands. Iblis alone refused to worship Adam. The very idea of a garden is hateful to the spirit of Nomadism.1 Man the gardener receives no reverence from the proud leader of the Seraphim. God said unto him (Iblis), What hindered thee from worshipping Adam, since I commanded thee? He answered, I am more excellent than he: thou hast created me of (ethereal) fire, and hast created him of clay (black mud). God said, Get thee down therefore from paradise, for it is not fit that thou behave thyself proudly therein.2

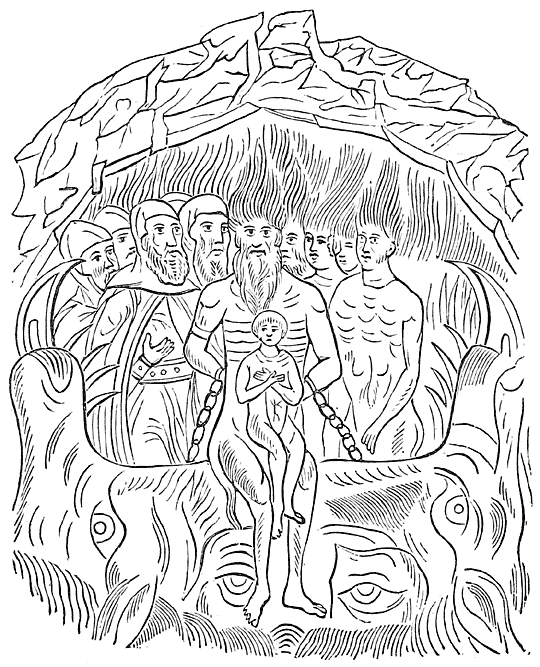

Fig. 4.—Hierarchy of Hell (Russian, Sixteenth Century).

The earnestness and self-devotion of the northern pagans in their resistance to Christianity impressed the finest minds in the Church profoundly. Some of the Fathers even quoted the enthusiasm of those whom they regarded as devotees of the Devil, to shame the apathy of christians. The Church could show no martyr braver than Rand, down whose throat St. Olaf made a viper creep, which gnawed through his side; and Rand was an example of thousands. This gave many of the early christians of the north a very serious view of the realm of Satan, and of Satan himself as a great potentate. It was increased by their discovery that the pagan kings—Satan’s subjects—had moral codes and law-courts, and energetically maintained justice. In this way there grew up a more dignified idea of Hell. The grotesque imps receded before the array of majestic devils, like Satan and Beelzebub; and these were invested with a certain grandeur and barbaric pride. They were regarded as rival monarchs who had refused to submit themselves to Jehovah, but they were deemed worthy of heroic treatment. The traces of this sentiment found in the ancient frescoes of Russia are of especial importance. Nothing can exceed the grandeur of the Hierarchy of Hell as they appear in some of these superb pictures. Satan is generally depicted with similar dignity to the king of heaven, from whom he is divided by a wall’s depth, sometimes even resembling him in all but complexion and hair (which is fire on Satan). There are frequent instances, as in the accompanying figure (4), where, in careful correspondence with the attitude of Christ on the Father’s knees, Satan supports the betrayer of Christ. Beside the king of Hell, seated in its Mouth, are personages of distinction, some probably representing those poets and sages of Greece and Rome, the prospect of whose damnation filled some of the first christian Fathers with such delight.

In Spain, when a Bishop is about to baptize one of the European Dukes of the Devil, he asks at the font what has become of his ancestors, naming them—all heathen. ‘They are all in hell!’ replies the Bishop. ‘Then there will I follow them,’ returns the Chief, and thereafter by no persuasion can he be induced to fare otherwise than to Hell. Gradually the Church made up its mind to ally itself with this obstinate barbaric pride and ambition. It was willing to give up anything whatever for a kingdom of this world, and to worship any number of Princes of Darkness, if they would give unto the Bishops such kingdoms, and the glory of them. They induced Esau to be baptized by promise of their aid in his oppressions, and free indulgences to all his passions; and then, by his help, they were able to lay before weaker Esaus the christian alternatives—Be baptized or burnt!

Not to have known how to conquer in bloodless victories the barbaric Esaus of the world by a virtue more pure, a heroism more patient, than theirs, and with that ‘sweet reasonableness of Christ,’ which is the latest epitaph on his tomb among the rich; not to have recognised the true nobility of the Dukes, and purified their pride to self-reverence, their passion to moral courage, their daring and freedom to a self-reliance at once gentle and manly; this was no doubt the necessary failure of a dogmatic and irrational system. But it is this which has made the christian Israel more of an impostor than its prototype, in every country to which it came steadily developing to a hypocritical imitator of the Esau whose birthright it stole by baptism. It speedily lost his magnanimity, but never his sword, which however it contrived to make at once meaner and more cruel by twisting it into thumbscrews and the like. For many centuries its voice has been, in a thin phonographic way, the voice of Jesus, but the hands are the hands of Esau with Samaël’s claw added.

1 The contest between the agriculturist and the (nomadic) shepherd is expressed in the legend that Cain and Abel divided the world between them, the one taking possession of the movable and the other of the immovable property. Cain said to his brother, ‘The earth on which thou standest is mine, then betake thyself to the air;’ but Abel replied, ‘The garments which thou wearest are mine, take them off.’—Midrash.

2 Sale’s Koran, vii. Al Araf. Iblis, the Mussulman name for the Devil, is probably a corruption of the word diabolus.

Chapter XIV.

Job and the Divider.

Hebrew Polytheism—Problem of Evil—Job’s disbelief in a future life—The Divider’s realm—Salted Sacrifices—Theory of Orthodoxy—Job’s reasoning—His humour—Impartiality of Fortune between the evil and good—Agnosticism of Job—Elihu’s eclecticism—Jehovah of the Whirlwind—Heresies of Job—Rabbinical legend of Job—Universality of the legend.

Israel is a flourishing vine,

Which bringeth forth fruit to itself;

According to the increase of his fruit

He hath multiplied his altars;

According to the goodness of his land

He hath made goodly images.

Their heart is divided: now shall they be found guilty;

He will break down their altars, he will spoil their images.

These words of the prophet Hosea (x. 1, 2) foreshadow the devil which the devout Jahvist saw growing steadily to enormous strength through all the history of Israel. The germ of this enemy may be found in our chapter on Fate; one of its earliest developments is indicated in the account already given of the partition between Jacob and Esau, and the superstition to which that led of a ghostly Antagonist, to whom a share had been irreversibly pledged. From the principle thus adopted, there grew a host of demons whom it was believed necessary to propitiate by offering them their share. A divided universe had for its counterpart a divided loyalty in the heart of the people. The growth of a belief in the supremacy of one God was far from being a real monotheism; as a matter of fact no primitive race has been monotheistic. In 2 Kings xvii. it is stated as a belief of the Jews that some Assyrians who had been imported into their territory (Samaria) were slain by lions because they knew not ‘the manner of the God of the land.’ Spinoza noticed the indications given in this and other narratives that the Jews believed that gods whose worship was intolerable within their own boundaries were yet adapted to other regions (Tractatus, ii.). With this state of mind it is not wonderful that when the Jews found themselves in those alien regions they apprehended that the gods of those countries might also employ lions on such as knew not their manner, but adhered to the worship of Jehovah too exclusively.

Among the Jews grew up a more spiritual class of minds, whose feeling towards the mongrel worship around them was that of abhorrence; but these had a very difficult cause to maintain. The popular superstitions were firmly rooted in the fact that terrible evils afflicted mankind, and in the further fact that these did not spare the most pious. Nay, it had for a long time been a growing belief that the bounties and afflictions of nature, instead of following the direction promised by the patriarchs,—rewarding the pious, punishing the wicked,—were distributed in a reverse way. Dives and Lazarus seemed to have their respective lots before any future paradise was devised for their equalisation—as indeed is natural, since Dives attends to his business, while Lazarus is investing his powers in Abraham’s bosom. Out of this experience there came at last the demand for a life beyond the grave, without whose redress the pious began to deem themselves of all men the most miserable. But before this heavenly future became a matter of common belief, there were theories which prepared, the way for it. It was held by the devout that the evils which afflicted the righteous were Jehovah’s tests of their loyalty to him, and that in the end such trials would be repaid. And when observation, following the theory, showed that they were not so repaid, it was said the righteousness had been unreal, the devotee was punished for hidden wickedness. When continued observation had proved that this theory too was false, and that piety was not paid in external bounties, either to the good man or his family, the solution of a future settlement was arrived at.

This simple process may be traced in various races, and in its several phases.

The most impressive presentation of the experiences under which the primitive secular theory of rewards and punishments perished, and that of an adjustment beyond the grave arose, is found in the Book of Job. The solution here reached—a future reward in this life—is an impossible one for anything more than an exceptional case. But the Book of Job displays how beautiful such an instance would be, showing afflictions to be temporary and destined to be followed by compensations largely outweighing them. It was a tremendous statement of the question—If a man die, shall he live again? Jehovah answered, ‘Yes’ out of the whirlwind, and raised Job out of the dust. But for the millions who never rose from the dust that voice was heard announcing their resurrection from a trial that pressed them even into the grave. It is remarkable that Job’s expression of faith that his Vindicator would appear on earth, should have become the one text of the Old Testament which has been adapted by christians to express faith in immortality. Job strongly disowns that faith.

There is hope for a tree,

If it be cut down, that it will sprout again,

And that its tender branches will not fail;

Though its root may have grown old in the earth,

And though its trunk be dead upon the ground,

At the scent of water it will bud,

And put forth boughs, like a young plant.

But man dieth and is gone for ever!

Yet I know that my Vindicator liveth,

And will stand up at length on the earth;

And though with my skin this body be wasted away,

Yet in my flesh shall I see God.

Yea, I shall see him my friend;

My eyes shall behold him no longer an adversary;

For this my soul panteth within me.1

The scenery and details of this drama are such as must have made an impression upon the mind of the ancient Jews beyond what is now possible for any existing people. In the first place, the locality was the land of Uz, which Jeremiah (Lam. iv. 21) points out as part of Edom, the territory traditionally ruled over by the great invisible Accuser of Israel, who had succeeded to the portion of Esau, adversary of their founder, Jacob. Job was within the perilous bounds. And yet here, where scape-goats were offered to deprecate Samaël, and where in ordinary sacrifices some item entered for the devil’s share, Job refused to pay any honour to the Power of the Place. He offered burnt-offerings alone for himself and his sons, these being exclusively given to Jehovah.2 Even after his children and his possessions were destroyed by this great adversary, Job offered his sacrifice without even omitting the salt, which was the Oriental seal of an inviolable compact between two, and which so especially recalled and consecrated the covenant with Jehovah.3 Among his twenty thousand animals, Azazel’s animal, the goat, is not even named. Job’s distinction was an absolute and unprecedented singleness of loyalty to Jehovah.

This loyalty of a disciple even in the enemy’s country is made the subject of a sort of boast by Jehovah when the Accuser enters. Postponing for the moment consideration of the character and office of this Satan, we may observe here that the trial which he challenges is merely a test of the sincerity of Job’s allegiance to Jehovah. The Accuser claims that it is all given for value received. These possessions are taken away.

This is but the framework around the philosophical poem in which all theories of the world are personified in grand council.

First of all Job (the Troubled) asks—Why? Orthodoxy answers. (Eliphaz was the son of Esau (Samaël), and his name here means that he was the Accuser in disguise. He, ‘God’s strength,’ stands for the Law. It affirms that God’s ways are just, and consequently afflictions imply previous sin.) Eliphaz repeats the question put by the Accuser in heaven—‘Was not thy fear of God thy hope?’ And he brings Job to the test of prayer, in which he has so long trusted. Eliphaz rests on revelation; he has had a vision; and if his revelation be not true, he challenges Job to disprove it by calling on God to answer him, or else securing the advocacy of some one of the heavenly host. Eliphaz says trouble does not spring out of the dust.

Job’s reply is to man and God—Point out the error! Grant my troubles are divine arrows, what have I done to thee, O watcher of men! Am I a sea-monster—and we imagine Job looking at his wasted limbs—that the Almighty must take precautions and send spies against me?

Then follows Bildad the Shuhite,—that is the ‘contentious,’ one of the descendants of Keturah (Abraham’s concubine), traditionally supposed to be inimical to the legitimate Abrahamic line, and at a later period identified as the Turks. Bildad, with invective rather than argument, charges that Job’s children had been slain for their sins, and otherwise makes a personal application of Eliphaz’s theology.

Job declares that since God is so perfect, no man by such standard could be proved just; that if he could prove himself just, the argument would be settled by the stronger party in his own favour; and therefore, liberated from all temptation to justify himself, he affirms that the innocent and the guilty are dealt with much in the same way. If it is a trial of strength between God and himself, he yields. If it is a matter of reasoning, let the terrors be withdrawn, and he will then be able to answer calmly. For the present, even if he were righteous, he dare not lift up his head to so assert, while the rod is upon him.

Zophar ‘the impudent’ speaks. Here too, probably, is a disguise: he is (says the LXX.) King of the Minæans, that is the Nomades, and his designation ‘the Naamathite,’ of unknown significance, bears a suspicious resemblance to Naamah, a mythologic wife of Samaël and mother of several devils. Zophar is cynical. He laughs at Job for even suggesting the notion of an argument between himself and God, whose wisdom and ways are unsearchable. He (God) sees man’s iniquity even when it looks as if he did not. He is deeper than hell. What can a man do but pray and acknowledge his sinfulness?

But Job, even in his extremity, is healthy-hearted enough to laugh too. He tells his three ‘comforters’ that no doubt Wisdom will die with them. Nevertheless, he has heard similar remarks before, and he is not prepared to renounce his conscience and common-sense on such grounds. And now, indeed, Job rises to a higher strain. He has made up his mind that after what has come upon him, he cares not if more be added, and challenges the universe to name his offence. So long as his transgression is ‘sealed up in a bag,’ he has a right to consider it an invention.4

Temanite Orthodoxy is shocked at all this. Eliphaz declares that Job’s assertion that innocent and guilty suffer alike makes the fear of God a vain thing, and discourages prayer. ‘With us are the aged and hoary-headed.’ (Job is a neologist.) Eliphaz paints human nature in Calvinistic colours.

Behold, (God) putteth no trust in his ministering spirits,

And the heavens are not pure in his sight;

Much less abominable and polluted man,

Who drinketh iniquity as water!

The wise have related, and they got it from the fathers to whom the land was given, and among whom no stranger was allowed to bring his strange doctrines, that affliction is the sign and punishment of wickedness.

Job merely says he has heard enough of this, and finds no wise man among them. He acknowledges that such reproaches add to his sorrows. He would rather contend with God than with them, if he could. But he sees a slight indication of divine favour in the remarkable unwisdom of his revilers, and their failure to prove their point.

Bildad draws a picture of what he considers would be the proper environment of a wicked man, and it closely resembles the situation of Job.

But Job reminds him that he, Bildad, is not God. It is God that has brought him so low, but God has been satisfied with his flesh. He has not yet uttered any complaint as to his conduct; and so he, Job, believes that his vindicator will yet appear to confront his accusers—the men who are so glib when his afflictor is silent.5

Zophar harps on the old string. Pretty much as some preachers go on endlessly with their pictures of the terrors which haunted the deathbeds of Voltaire and Paine, all the more because none are present to relate the facts. Zophar recounts how men who seemed good, but were not, were overtaken by asps and vipers and fires from heaven.

But Job, on the other hand, has a curious catalogue of examples in which the notoriously wicked have lived in wealth and gaiety. And if it be said God pays such off in their children, Job denies the justice of that. It is the offender, and not his child, who ought to feel it. The prosperous and the bitter in soul alike lie down in the dust at last, the good and the evil; and Job is quite content to admit that he does not understand it. One thing he does understand: ‘Your explanations are false.’

But Eliphaz insists on Job having a dogma. If the orthodox dogma is not true, put something in its place! Why are you afflicted? What is, your theory? Is it because God was afraid of your greatness? It must be as we say, and you have been defrauding and injuring people in secret.

Job, having repeated his ardent desire to meet God face to face as to his innocence, says he can only conclude that what befalls him and others is what is ‘appointed’ for them. His terror indeed arises from that: the good and the evil seem to be distributed without reference to human conduct. How darkness conspires with the assassin! If God were only a man, things might be different; but as it is, ‘what he desireth that he doeth,’ and ‘who can turn him?’

Bildad falls back on his dogma of depravity. Man is a ‘worm,’ a ‘reptile.’ Job finds that for a worm Bildad is very familiar with the divine secrets. If man is morally so weak he should be lowly in mind also. God by his spirit hath garnished the heavens; his hand formed the ‘crooked serpent’—

Lo! these are but the borders of his works;

How faint the whisper we have heard of him!

But the thunder of his power who can understand?

Job takes up the position of the agnostic, and the three ‘Comforters’ are silenced. The argument has ended where it had to end. Job then proceeds with sublime eloquence. A man may lose all outward things, but no man or god can make him utter a lie, or take from him his integrity, or his consciousness of it. Friends may reproach him, but he can see that his own heart does not. That one superiority to the wicked he can preserve. In reviewing his arguments Job is careful to say that he does not maintain that good and evil men are on an equality. For one thing, when the wicked man is in trouble he cannot find resource in his innocence. ‘Can he delight himself in the Almighty?’ When such die, their widows do not bewail them. Men do not befriend oppressors when they come to want. Men hiss them. And with guilt in their heart they feel their sorrows to be the arrows of God, sent in anger. In all the realms of nature, therefore, amid its powers, splendours, and precious things, man cannot find the wisdom which raises him above misfortune, but only in his inward loyalty to the highest, and freedom from moral evil.

Then enters a fifth character, Elihu, whose plan is to mediate between the old dogma and the new agnostic philosophy. He is Orthodoxy rationalised. Elihu’s name is suggestive of his ambiguity; it seems to mean one whose ‘God is He’ and he comes from the tribe of Buz, whose Hebrew meaning might almost be represented in that English word which, with an added z, would best convey the windiness of his remarks. Buz was the son of Milkah, the Moon, and his descendant so came fairly by his theologic ‘moonshine’ of the kind which Carlyle has so well described in his account of Coleridgean casuistry. Elihu means to be fair to both sides! Elihu sees some truth in both sides! Eclectic Elihu! Job is perfectly right in thinking he had not done anything to merit his sufferings, but he did not know what snares were around him, and how he might have done something wicked but for his affliction. Moreover, God ruins people now and then just to show how he can lift them up again. Job ought to have taken this for granted, and then to have expressed it in the old abject phraseology, saying, ‘I have received chastisement; I will offend no more! What I see not, teach thou me!’ (A truly Elihuic or ‘contemptible’ answer to Job’s sensible words, ‘Why is light given to a man whose way is hid?’ Why administer the rod which enlightens as to the anger but not its cause, or as to the way of amend?) In fact the casuistic Elihu casts no light whatever on the situation. He simply overwhelms him with metaphors and generalities about the divine justice and mercy, meant to hide this new and dangerous solution which Job had discovered—namely, that the old dogmatic theories of evil were proved false by experience, and that a good man amid sorrow should admit his ignorance, but never allow terror to wring from him the voice of guilt, nor the attempt to propitiate divine wrath.

When Jehovah appears on the scene, answering Job out of the whirlwind, the tone is one of wrath, but the whole utterance is merely an amplification of what Job had said—what we see and suffer are but fringes of a Whole we cannot understand. The magnificence and wonder of the universe celebrated in that voice of the whirlwind had to be given the lame and impotent conclusion of Job ‘abhorring himself,’ and ‘repenting in dust and ashes.’ The conventional Cerberus must have his sop. But none the less does the great heart of this poem reveal the soul that was not shaken or divided in prosperity or adversity. The burnt-offering of his prosperous days, symbol of a worship which refused to include the supposed powers of mischief, was enjoined on Job’s Comforters. They must bend to him as nearer God than they. And in his high philosophy Job found what is symbolised in the three daughters born to him: Jemima (the Dove, the voice of the returning Spring); Kezia (Cassia, the sweet incense); Kerenhappuch (the horn of beautiful colour, or decoration).

From the Jewish point of view this triumph of Job represented a tremendous heresy. The idea that afflictions could befall a man without any reference to his conduct, and consequently not to be influenced by the normal rites and sacrifices, is one fatal to a priesthood. If evil may be referred in one case to what is going on far away among gods in obscurities of the universe, and to some purpose beyond the ken of all sages, it may so be referred in all cases, and though burnt-offerings may be resorted to formally, they must cease when their powerlessness is proved. Hence the Rabbins have taken the side of Job’s Comforters. They invented a legend that Job had been a great magician in Egypt, and was one of those whose sorceries so long prevented the escape of Israel. He was converted afterwards, but it is hinted that his early wickedness required the retribution he suffered. His name was to them the troubler troubled.

Heretical also was the theory that man could get along without any Angelolatry or Demon-worship. Job in his singleness of service, fearing God alone, defying the Seraphim and Cherubim from Samaël down to do their worst, was a perilous figure. The priests got no part of any burnt-offering. The sin-offering was of almost sumptuary importance. Hence the rabbinical theory, already noticed, that it was through neglect of these expiations to the God of Sin that the morally spotless Job came under the power of his plagues.

But for precisely the same reasons the story of Job became representative to the more spiritual class of minds of a genuine as contrasted with a nominal monotheism, and the piety of the pure, the undivided heart. Its meaning is so human that it is not necessary to discuss the question of its connection with the story of Hariśchandra, or whether its accent was caught from or by the legends of Zoroaster and of Buddha, who passed unscathed through the ordeals of Ahriman and Mara. It was repeated in the encounters of the infant Christ with Herod, and of the adult Christ with Satan. It was repeated in the unswerving loyalty of the patient Griselda to her husband. It is indeed the heroic theme of many races and ages, and it everywhere points to a period when the virtues of endurance and patience rose up to match the agonies which fear and weakness had tried to propitiate,—when man first learned to suffer and be strong.

1 Noyes’ Translation.

2 Eisenmenger, Entd. Jud. i. 836.

3 Job. i. 22, the literal rendering of which is, ‘In all this Job sinned not, nor gave God unsalted.’ This translation I first heard from Dr. A. P. Peabody, sometime President of Harvard University, from whom I have a note in which he says:—‘The word which I have rendered gave is appropriate to a sacrifice. The word I have rendered unsalted means so literally; and is in Job vi. 6 rendered unsavory. It may, and sometimes does, denote folly, by a not unnatural metaphor; but in that sense the word gave—an offertory word—is out of place.’ Waltonus (Bib. Polyg.) translates ‘nec dedit insulsum Deo;’ had he rendered תִּפְלָה by insalsum it would have been exact. The horror with which demons and devils are supposed to regard salt is noticed, i. 288.

4 Gesenius so understands verse 17 of chap. xiv.

5 The much misunderstood and mistranslated passage, xix. 25–27 (already quoted), is certainly referable to the wide-spread belief that as against each man there was an Accusing Spirit, so for each there was a Vindicating Spirit. These two stood respectively on the right and left of the balances in which the good and evil actions of each soul were weighed against each other, each trying to make his side as heavy as possible. But as the accusations against him are made by living men, and on earth, Job is not prepared to consider a celestial acquittal beyond the grave as adequate.

Chapter XV.

Satan.

Public Prosecutors—Satan as Accuser—English Devil-worshipper—Conversion by Terror—Satan in the Old Testament—The trial of Joshua—Sender of Plagues—Satan and Serpent—Portrait of Satan—Scapegoat of Christendom—Catholic ‘Sight of Hell’—The ally of Priesthoods.

There is nothing about the Satan of the Book of Job to indicate him as a diabolical character. He appears as a respectable and powerful personage among the sons of God who present themselves before Jehovah, and his office is that of a public prosecutor. He goes to and fro in the earth attending to his duties. He has received certificates of character from A. Schultens, Herder, Eichorn, Dathe, Ilgen, who proposed a new word for Satan in the prologue of Job, which would make him a faithful but too suspicious servant of God.

Such indeed he was deemed originally; but it is easy to see how the degradation of such a figure must have begun. There is often a clamour in England for the creation of Public Prosecutors; yet no doubt there is good ground for the hesitation which its judicial heads feel in advising such a step. The experience of countries in which Prosecuting Attorneys exist is not such as to prove the institution one of unmixed advantage. It is not in human nature for an official person not to make the most of the duty intrusted to him, and the tendency is to raise the interest he specially represents above that of justice itself. A defeated prosecutor feels a certain stigma upon his reputation as much as a defeated advocate, and it is doubtful whether it be safe that the fame of any man should be in the least identified with personal success where justice is trying to strike a true balance. The recent performances of certain attorneys in England and America retained by Societies for the Suppression of Vice strikingly illustrate the dangers here alluded to. The necessity that such salaried social detectives should perpetually parade before the community as purifiers of society induces them to get up unreal cases where real ones cannot be easily discovered. Thus they become Accusers, and from this it is an easy step to become Slanderers; nor is it a very difficult one which may make them instigators of the vices they profess to suppress.

The first representations of Satan show him holding in his hand the scales; but the latter show him trying slyly with hand or foot to press down that side of the balance in which the evil deeds of a soul are being weighed against the good. We need not try to track archæologically this declension of a Prosecutor, by increasing ardour in his office, through the stages of Accuser, Adversary, Executioner, and at last Rival of the legitimate Rule, and tempter of its subjects. The process is simple and familiar. I have before me a little twopenny book,1 which is said to have a vast circulation, where one may trace the whole mental evolution of Satan. The ancient Devil-worshipper who has reappeared with such power in England tells us that he was the reputed son of a farmer, who had to support a wife and eleven children on from 7s. to 9s. per week, and who sent him for a short time to school. ‘My schoolmistress reproved me for something wrong, telling me that God Almighty took notice of children’s sins. This stuck to my conscience a great while; and who this God Almighty could be I could not conjecture; and how he could know my sins without asking my mother I could not conceive. At that time there was a person named Godfrey, an exciseman, in the town, a man of a stern and hard-favoured countenance, whom I took notice of for having a stick covered with figures, and an ink-bottle hanging at the button-hole of his coat. I imagined that man to be employed by God Almighty to take notice and keep an account of children’s sins; and once I got into the market-house and watched him very narrowly, and found that he was always in a hurry, by his walking so fast; and I thought he had need to hurry, as he must have a deal to do to find out all the sins of children!’ This terror caused the little Huntington to say his prayers. ‘Punishment for sin I found was to be inflicted after death, therefore I hated the churchyard, and would travel any distance round rather than drag my guilty conscience over that enchanted spot.’

The child is father to the man. When Huntington, S.S., grew up, it was to record for the thousands who listened to him as a prophet his many encounters with the devil. The Satan he believes in is an exact counterpart of the stern, hard-favoured exciseman whom he had regarded as God’s employé. On one occasion he writes, ‘Satan began to tempt me violently that there was no God, but I reasoned against the belief of that from my own experience of his dreadful wrath, saying, How can I credit this suggestion, when (God’s) wrath is already revealed in my heart, and every curse in his book levelled at my head.’ (That seems his only evidence of God’s existence—his wrath!) ‘The Devil answered that the Bible was false, and only wrote by cunning men to puzzle and deceive people. ‘There is no God,’ said the adversary, ‘nor is the Bible true.’ ... I asked, ‘Who, then, made the world?’ He replied, ‘I did, and I made men too.’ Satan, perceiving my rationality almost gone, followed me up with another temptation; that as there was no God I must come back to his work again, else when he had brought me to hell he would punish me more than all the rest. I cried out, ‘Oh, what will become of me! what will become of me!’ He answered that there was no escape but by praying to him; and that he would show me some lenity when he took me to hell. I went and sat in my tool-house halting between two opinions; whether I should petition Satan, or whether I should keep praying to God, until I could ascertain the consequences. While I was thinking of bending my knees to such a cursed being as Satan, an uncommon fear of God sprung up in my heart to keep me from it.’

In other words, Mr. Huntington wavered between the petitions ‘Good Lord! Good Devil!’ The question whether it were more moral, more holy, to worship the one than the other did not occur to him. He only considers which is the strongest—which could do him the most mischief—which, therefore, to fear the most; and when Satan has almost convinced him in his own favour, he changes round to God. Why? Not because of any superior goodness on God’s part. He says, ‘An uncommon fear of God sprung up in my heart.’ The greater terror won the day; that is to say, of two demons he yielded to the stronger. Such an experience, though that of one living in our own time, represents a phase in the development of the relation between God and Satan which would have appeared primitive to an Assyrian two thousand years ago. The ethical antagonism of the two was then much more clearly felt. But this bit of contemporary superstition may bring before us the period when Satan, from having been a Nemesis or Retributive Agent of the divine law, had become a mere personal rival of his superior.

Satan, among the Jews, was at first a generic term for an adversary lying in wait. It is probably the furtive suggestion at the root of this Hebrew word which aided in its selection as the name for the invisible adverse powers when they were especially distinguished. But originally no special personage, much less any antagonist of Jehovah, was signified by the word. Thus we read: ‘And God’s anger was kindled because he (Balaam) went; and the angel of the Lord stood in the way for a Satan against him.... And the ass saw the angel of the Lord standing in the way and his sword drawn in his hand.’2 The eyes of Balaam are presently opened, and the angel says, ‘I went out to be a Satan to thee because the way is perverse before me.’ The Philistines fear to take David with them to battle lest he should prove a Satan to them, that is, an underhand enemy or traitor.3 David called those who wished to put Shimei to death Satans;4 but in this case the epithet would have been more applicable to himself for affecting to protect the honest man for whose murder he treacherously provided.5

That it was popularly used for adversary as distinct from evil appears in Solomon’s words, ‘There is neither Satan nor evil occurrent.’6 Yet it is in connection with Solomon that we may note the entrance of some of the materials for the mythology which afterwards invested the name of Satan. It is said that, in anger at his idolatries, ‘the Lord stirred up a Satan unto Solomon, Hadad the Edomite: he was of the king’s seed in Edom.’7 Hadad, ‘the Sharp,’ bore a name next to that of Esau himself for the redness of his wrath, and, as we have seen in a former chapter, Edom was to the Jews the land of ‘bogeys.’ ‘Another Satan,’ whom the Lord ‘stirred up,’ was the Devastator, Prince Rezon, founder of the kingdom of Damascus, of whom it is said, ‘he was a Satan to Israel all the days of Solomon.’8 The human characteristics of supposed ‘Scourges of God’ easily pass away. The name that becomes traditionally associated with calamities whose agents were ‘stirred up’ by the Almighty is not allowed the glory of its desolations. The word ‘Satan,’ twice used in this chapter concerning Solomon’s fall, probably gained here a long step towards distinct personification as an eminent national enemy, though there is no intimation of a power daring to oppose the will of Jehovah. Nor, indeed, is there any such intimation anywhere in the ‘canonical’ books of the Old Testament. The writer of Psalm cix., imprecating for his adversaries, says: ‘Set thou a wicked man over him; and let Satan stand at his right hand. When he shall be judged, let him be condemned; and let his prayer become sin.’ In this there is an indication of a special Satan, but he is supposed to be an agent of Jehovah. In the catalogue of the curses invoked of the Lord, we find the evils which were afterwards supposed to proceed only from Satan. The only instance in the Old Testament in which there is even a faint suggestion of hostility towards Satan on the part of Jehovah is in Zechariah. Here we find the following remarkable words: ‘And he showed me Joshua the high priest standing before the angel of Jehovah, and the Satan standing at his right hand to oppose him. And Jehovah said unto Satan, Jehovah rebuke thee, O Satan; even Jehovah, that hath chosen Jerusalem, rebuke thee: is not this a brand plucked out of the fire? Now Joshua was clothed with filthy garments, and stood before the angel. And he answered and spake to those that stood before him, saying, Take away the filthy garments from him. And to him he said, Lo, I have caused thine iniquity to pass from thee, and I will clothe thee with goodly raiment.’9

Here we have a very fair study and sketch of that judicial trial of the soul for which mainly the dogma of a resurrection after death was invented. The doctrine of future rewards and punishments is not one which a priesthood would invent or care for, so long as they possessed unrestricted power to administer such in this life. It is when an alien power steps in to supersede the priesthood—the Gallio too indifferent whether ceremonial laws are carried out to permit the full application of terrestrial cruelties—that the priest requires a tribunal beyond the grave to execute his sentence. In this picture of Zechariah we have this invisible Celestial Court. The Angel of Judgment is in his seat. The Angel of Accusation is present to prosecute. A poor filthy wretch appears for trial. What advocate can he command? Where is Michael, the special advocate of Israel? He does not recognise one of his clients in this poor Joshua in his rags. But lo! suddenly Jehovah himself appears; reproves his own commissioned Accuser; declares Joshua a brand plucked from the burning (Tophet); orders a change of raiment, and, condoning his offences, takes him into his own service. But in all this there is nothing to show general antagonism between Jehovah and Satan, but the reverse.

When we look into the Book of Job we find a Satan sufficiently different from any and all of those mentioned under that name in other parts of the Old Testament to justify the belief that he has been mainly adapted from the traditions of other regions. The plagues and afflictions which in Psalm cix. are invoked from Jehovah, even while Satan is mentioned as near, are in the Book of Job ascribed to Satan himself. Jehovah only permits Satan to inflict them with a proviso against total destruction. Satan is here named as a personality in a way not known elsewhere in the Old Testament, unless it be in 1 Chron. xxi. 1, where Satan (the article being in this single case absent) is said to have ‘stood up against Israel, and provoked David to number Israel.’ But in this case the uniformity of the passage with the others (excepting those in Job) is preserved by the same incident being recorded in 2 Sam. xxiv. 1, ‘The anger of Jehovah was kindled against Israel, and he (Jehovah) moved David against them to say, Go number Israel and Judah.’

It is clear that, in the Old Testament, it is in the Book of Job alone that we find Satan as the powerful prince of an empire which is distinct from that of Jehovah,—an empire of tempest, plague, and fire,—though he presents himself before Jehovah, and awaits permission to exert his power on a loyal subject of Jehovah. The formality of a trial, so dear to the Semitic heart, is omitted in this case. And these circumstances confirm the many other facts which prove this drama to be largely of non-Semitic origin. It is tolerably clear that the drama of Hariśchandra in India and that of Job were both developed from the Sanskrit legends mentioned in our chapter on Viswámitra; and it is certain that Aryan and Semitic elements are both represented in the figure of Satan as he has passed into the theology of Christendom.

Nor indeed has Satan since his importation into Jewish literature in this new aspect, much as the Rabbins have made of him, ever been assigned the same character among that people that has been assigned him in Christendom. He has never replaced Samaël as their Archfiend. Rabbins have, indeed, in later times associated him with the Serpent which seduced Eve in Eden; but the absence of any important reference to that story in the New Testament is significant of the slight place it had in the Jewish mind long after the belief in Satan had become popular. In fact, that essentially Aryan myth little accorded with the ideas of strife and immorality which the Jews had gradually associated with Samaël. In the narrative, as it stands in Genesis, it is by no means the Serpent that makes the worst appearance. It is Jehovah, whose word—that death shall follow on the day the apple is eaten—is falsified by the result; and while the Serpent is seen telling the truth, and guiding man to knowledge, Jehovah is represented as animated by jealousy or even fear of man’s attainments. All of which is natural enough in an extremely primitive myth of a combat between rival gods, but by no means possesses the moral accent of the time and conditions amid which Jahvism certainly originated. It is in the same unmoral plane as the contest of the Devas and Asuras for the Amrita, in Hindu mythology, a contest of physical force and wits.

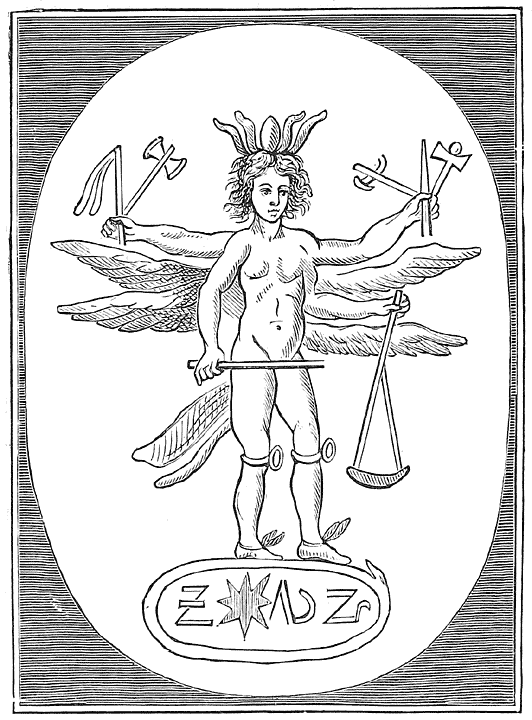

Fig. 5.—Gnostic Figure (Ste. Genevieve Collection).

The real development of Satan among the Jews was from an accusing to an opposing spirit, then to an agent of punishment—a hated executioner. The fact that the figure here given (Fig. 5) was identified by one so familiar with Semitic demonology as Calmet as a representation of him, is extremely interesting. It was found among representations of Cherubim, and on the back of one somewhat like it is a formula of invocation against demons. The countenance is of that severe beauty which the Greeks ascribed to Nemesis. Nemesis has at her feet the wheel and rudder, symbols of her power to overtake the evil-doer by land or sea; the feet of this figure are winged for pursuit. He has four hands. In one he bears the lamp which, like Lucifer, brings light on the deed of darkness. As to others, he answers Baruch’s description (Ep. 13, 14) of the Babylonian god, ‘He hath a sceptre in his hand like a man, like a judge of the kingdom—he hath in his hand a sword and an axe.’ He bears nicely-graduated implements of punishment, from the lash that scourges to the axe that slays; and his retributive powers are supplemented by the scorpion tail. At his knees are signets; whomsoever he seals are sealed. He has the terrible eyes which were believed able to read on every forehead a catalogue of sins invisible to mortals, a power that made women careful of their veils, and gave meaning to the formula ‘Get thee behind me!’10

Now this figure, which Calmet believed to be Satan, bears on its reverse, ‘The Everlasting Sun.’ He is a god made up of Egyptian and Magian forms, the head-plumes belonging to the one, the multiplied wings to the other. Matter (Hist. Crit. de Gnost.) reproduces it, and says that ‘it differs so much from all else of the kind as to prove it the work of an impostor.’ But Professor C. W. King has a (probably fifth century) gem in his collection evidently a rude copy of this (reproduced in his ‘Gnostics,’ Pl. xi. 3), on the back of which is ‘Light of Lights;’ and, in a note which I have from him, he says that it sufficiently proves Matter wrong, and that this form was primitive. In one gem of Professor King’s (Pl. v. 1) the lamp is also carried, and means the ‘Light of Lights.’ The inscription beneath, within a coiled serpent, is in corrupt cuneiform characters, long preserved by the Magi, though without understanding them. There is little doubt, therefore, that the instinct of Calmet was right, and that we have here an early form of the detective and retributive Magian deity ultimately degraded to an accusing spirit, or Satan.

Although the Jews did not identify Satan with their Scapegoat, yet he has been veritably the Scapegoat among devils for two thousand years. All the nightmares and phantasms that ever haunted the human imagination have been packed upon him unto this day, when it is almost as common to hear his name in India and China as in Europe and America. In thus passing round the world, he has caught the varying features of many fossilised demons: he has been horned, hoofed, reptilian, quadrupedal, anthropoid, anthropomorphic, beautiful, ugly, male, female; the whites painted him black, and the blacks, with more reason, painted him white. Thus has Satan been made a miracle of incongruities. Yet through all these protean shapes there has persisted the original characteristic mentioned. He is prosecutor and executioner under the divine government, though his office has been debased by that mental confusion which, in the East, abhors the burner of corpses, and, in the West, regards the public hangman with contempt; the abhorrence, in the case of Satan, being intensified by the supposition of an overfondness for his work, carried to the extent of instigating the offences which will bring him victims.

In a well-known English Roman Catholic book11 of recent times, there is this account of St. Francis’ visit to hell in company with the Angel Gabriel:—‘St. Francis saw that, on the other side of (a certain) soul, there was another devil to mock at and reproach it. He said, Remember where you are, and where you will be for ever; how short the sin was, how long the punishment. It is your own fault; when you committed that mortal sin you knew how you would be punished. What a good bargain you made to take the pains of eternity in exchange for the sin of a day, an hour, a moment. You cry now for your sin, but your crying comes too late. You liked bad company; you will find bad company enough here. Your father was a drunkard, look at him there drinking red-hot fire. You were too idle to go to mass on Sundays; be as idle as you like now, for there is no mass to go to. You disobeyed your father, but you dare not disobey him who is your father in hell.’

This devil speaks as one carrying out the divine decrees. He preaches. He utters from his chasuble of flame the sermons of Father Furniss. And, no doubt, wherever belief in Satan is theological, this is pretty much the form which he assumes before the mind (or what such believers would call their mind, albeit really the mind of some Syrian dead these two thousand years). But the Satan popularly personalised was man’s effort to imagine an enthusiasm of inhumanity. He is the necessary appendage to a personalised Omnipotence, whose thoughts are not as man’s thoughts, but claim to coerce these. His degradation reflects the heartlessness and the ingenuity of torture which must always represent personal government with its catalogue of fictitious crimes. Offences against mere Majesty, against iniquities framed in law, must be doubly punished, the thing to be secured being doubly weak. Under any theocratic government law and punishment would become the types of diabolism. Satan thus has a twofold significance. He reports what powerful priesthoods found to be the obstacles to their authority; and he reports the character of the priestly despotisms which aimed to obstruct human development.

1 ‘The Kingdom of Heaven Taken by Prayer.’ By William Huntington, S.S. This title is explained to be ‘Sinner Saved,’ otherwise one might understand the letters to signify a Surviving Syrian.

2 Num. xxii. 22.

3 1 Sam. xxix. 4.

4 2 Sam. xix. 22.

5 1 Kings ii. 9.

6 1 Kings v. 4.

7 1 Kings xi. 14.

8 1 Kings xi. 25.

9 Zech. iii.

10 Cf. Rev. vii. 3.

11 ‘The Sight of Hell,’ prepared, as one of a ‘Series of Books for Children and Young Persons,’ by the Rev. Father Furniss, C.S.S.R., by authority of his Superiors.