Chapter XVI.

Religious Despotism.

Pharaoh and Herod—Zoroaster’s mother—Ahriman’s emissaries—Kansa and Krishna—Emissaries of Kansa—Astyages and Cyrus—Zohák—Bel and the Christian.

The Jews had already, when Christ appeared, formed the theory that the hardening of Pharaoh’s heart, and his resistance to the departure of Israel from Egypt, were due to diabolical sorcery. The belief afterwards matured; that Edom (Esau or Samaël) was the instigator of Roman aggression was steadily forming. The mental conditions were therefore favourable to the growth of a belief in the Jewish followers of Christ that the hostility to the religious movement of their time was another effort on the part of Samaël to crush the kingdom of God. Herod was not, indeed, called Satan or Samaël, nor was Pharaoh; but the splendour and grandeur of this Idumean (the realm of Esau), notwithstanding his oppressions and crimes, had made him a fair representative to the people of the supernatural power they dreaded. Under these circumstances it was a powerful appeal to the sympathies of the Jewish people to invent in connection with Herod a myth exactly similar to that associated with Pharaoh,—namely, a conspiracy with sorcerers, and consequent massacre of all new-born children.

The myths which tell of divine babes supernaturally saved from royal hostility are veritable myths, even where they occur so late in time that historic names and places are given; for, of course, it is impossible that by any natural means either Pharaoh or Herod should be aware of the peculiar nature of any particular infant born in their dominions. Such traditions, when thus presented in historical guise, can only be explained by reference to corresponding fables written out in simpler mythic form; while it is especially necessary to remember that such corresponding narratives may be of independent ethnical origin, and that the later in time may be more primitive spiritually.

In the Legend of Zoroaster1 his mother Dogdo, previous to his birth, has a dream in which she sees a black cloud, which, like the wing of some vast bird, hides the sun, and brings on frightful darkness. This cloud rains down on her house terrible beasts with sharp teeth,—tigers, lions, wolves, rhinoceroses, serpents. One monster especially attacks her with great fury, and her unborn babe speaks in reassuring terms. A great light rises and the beasts fall. A beautiful youth appears, hurls a book at the Devas (Devils), and they fly, with exception of three,—a wolf, a lion, and a tiger. These, however, the youth drives away with a luminous horn. He then replaces the holy infant in the womb, and says to the mother: ‘Fear nothing! The King of Heaven protects this infant. The earth waits for him. He is the prophet whom Ormuzd sends to his people: his law will fill the world with joy: he will make the lion and the lamb drink in the same place. Fear not these ferocious beasts; why should he whom Ormuzd preserves fear the enmity of the whole world?’ With these words the youth vanished, and Dogdo awoke. Repairing to an interpreter, she was told that the Horn meant the grandeur of Ormuzd; the Book was the Avesta; the three Beasts betokened three powerful enemies.

Zoroaster was born laughing. This prodigy being noised abroad, the Magicians became alarmed, and sought to slay the child. One of them raised a sword to strike him, but his arm fell to the ground. The Magicians bore the child to the desert, kindled a fire and threw him into it, but his mother afterwards found him sleeping tranquilly and unharmed in the flames. Next he was thrown in front of a drove of cows and bulls, but the fiercest of the bulls stood carefully over the child and protected him. The Magicians killed all the young of a pack of wolves, and then cast the infant Zoroaster to them that they might vent their rage upon him, but the mouths of the wolves were shut. They abandoned the child on a lonely mountain, but two ewes came and suckled him.

Zoroaster’s father respected the ministers of the Devas (Magi), but his child rebuked him. Zoroaster walked on the water (crossing a great river where was no bridge) on his way to Mount Iran where he was to receive the Law. It was then he had the vision of the battle between the two serpent armies,—the white and black adders, the former, from the South, conquering the latter, which had come from the North to destroy him.

The Legend of the Infant Krishna is as follows:—The tyrant Kansa, having given his sister Devaki in marriage to Vasudéva, as he was returning from the wedding heard a voice declare, ‘The eighth son of Devaki is destined to be thy destroyer.’ Alarmed at this, Kansa cast his sister and her husband into a prison with seven iron doors, and whenever a son was born he caused it to be instantly destroyed. When Devaki became pregnant the eighth time, Brahma and Siva, with attending Devas, appeared and sang: ‘O favoured among women! in thy delivery all nature shall have cause to exult! How ardently we long to behold that face for the sake of which we have coursed round three worlds!’ When Krishna was born a chorus of celestial spirits saluted him; the room was illumined with supernatural light. While Devaki was weeping at the fatal decree of Kansa that her son should be destroyed, a voice was heard by Vasudéva saying: ‘Son of Yadu, carry this child to Gokul, on the other side of the river Jumna, to Nauda, whose wife has just given birth to a daughter. Leave him and bring the girl hither.’ At this the seven doors swung open, deep sleep fell on the guards, and Vasudéva went forth with the holy infant in his arms. The river Jumna was swollen, but the waters, having kissed the feet of Krishna, retired on either side, opening a pathway. The great serpent of Vishnu held its hood over this new incarnation of its Lord. Beside sleeping Nauda and his wife the daughter was replaced by the son, who was named Krishna, the Dark.

When all this had happened a voice came to Kansa saying: ‘The boy destined to destroy thee is born, and is now living.’ Whereupon Kansa ordered all the male children in his kingdom to be destroyed. This being ineffectual, the whereabouts of Krishna were discovered; but the messenger who was sent to destroy the child beheld its image in the water and adored it. The Rakshasas worked in the interest of Kansa. One approached the divine child in shape of a monstrous bull whose head he wrung off; and he so burned in the stomach of a crocodile which had swallowed him that the monster cast him from his mouth unharmed.

Finally, as a youth, Krishna, after living some time as a herdsman, attacked the tyrant Kansa, tore the crown from his head, and dragged him by his hair a long way; with the curious result that Kansa became liberated from the three worlds, such virtue had long thinking about the incarnate one, even in enmity!

The divine beings represented in these legends find their complement in the fabulous history of Cyrus; and the hostile powers which sought their destruction are represented in demonology by the Persian tyrant-devil Zohák. The name of Astyages, the grandfather of Cyrus, has been satisfactorily traced to Ashdahák, and Ajis Daháka, the ‘biting snake.’ The word thus connects him with Vedic Ahi and with Iranian Zohák, the tyrant out of whose shoulders a magician evoked two serpents which adhered to him and became at once his familiars and the arms of his cruelty. As Astyages, the last king of Media, he had a dream that the offspring of his daughter Mandane would reign over Asia. He gave her in marriage to Cambyses, and when she bore a child (Cyrus), committed it to his minister Harpagus to be slain. Harpagus, however, moved with pity, gave it to a herdsman of Astyages, who substituted for it a still-born child, and having so satisfied the tyrant of its death, reared Cyrus as his own son.

The luminous Horn of the Zoroastrian legend and the diabolism of Zohák are both recalled in the Book of Daniel (viii.) in the terrific struggle of the ram and the he-goat. The he-goat, ancient symbol of hairy Esau, long idealised into the Invisible Foe of Israel, had become associated also with Babylon and with Nimrod its founder, the Semitic Zohák. But Bel, conqueror of the Dragon, was the founder of Babylon, and to Jewish eyes the Dragon was his familiar; to the Jews he represented the tyranny and idolatry of Nimrod, the two serpents of Zohák. When Cyrus supplanted Astyages, this was the idol he found the Babylonians worshipping until Daniel destroyed it. And so, it would appear, came about the fact that to the Jews the power of Christendom came to be represented as the Reign of Bel. One can hardly wonder at that. If ever there were cruelty and oppression passing beyond the limit of mere human capacities, it has been recorded in the tragical history of Jewish sufferings. The disbeliever in præternatural powers of evil can no less than others recognise in this ‘Bel and the Christian,’ which the Jews substituted for ‘Bel and the Dragon,’ the real archfiend—Superstition, turning human hearts to stone when to stony gods they sacrifice their own humanity and the welfare of mankind.

1 M. Anquetil Du Perron’s ‘Zendavesta et Vie de Zoroastre.’

Chapter XVII.

The Prince of this World.

Temptations—Birth of Buddha—Mara—Temptation of power—Asceticism and Luxury—Mara’s menaces—Appearance of the Buddha’s Vindicator—Ahriman tempts Zoroaster—Satan and Christ—Criticism of Strauss—Jewish traditions—Hunger—Variants.

The Devil, having shown Jesus all the kingdoms of this world, said, ‘All this power will I give thee, and the glory of them: for that is delivered unto me, and to whomsoever I will I give it,’ The theory thus announced is as a vast formation underlying many religions. As every religion begins as an ideal, it must find itself in antagonism to the world at large; and since the social and political world are themselves, so long as they last, the outcome of nature, it is inevitable that in primitive times the earth should be regarded as a Satanic realm, and the divine world pictured elsewhere. A legitimate result of this conclusion is asceticism, and belief in the wickedness of earthly enjoyments. To men of great intellectual powers, generally accompanied as they are with keen susceptibilities of enjoyment and strong sympathies, the renunciation of this world must be as a living burial. To men who, amid the corruptions of the world, feel within them the power to strike in with effect, or who, seeing ‘with how little wisdom the world is governed,’ are stirred by the sense of power, the struggle against the temptation to lead in the kingdoms of this world is necessarily severe. Thus simple is the sense of those temptations which make the almost invariable ordeal of the traditional founders of religions. As in earlier times the god won his spurs, so to say, by conquering some monstrous beast, the saint or saviour must have overcome some potent many-headed world, with gems for scales and double-tongue, coiling round the earth, and thence, like Lilith’s golden hair, round the heart of all surrendered to its seductions.

It is remarkable to note the contrast between the visible and invisible worlds which surrounded the spiritual pilgrimage of Sakya Muni to Buddhahood or enlightenment. At his birth there is no trace of political hostility: the cruel Kansa, Herod, Magicians seeking to destroy, are replaced by the affectionate force of a king trying to retain his son. The universal traditions reach their happy height in the ecstatic gospels of the Siamese.1 The universe was illumined; all jewels shown with unwonted lustre; the air was full of music; all pain ceased; the blind saw, the deaf heard; the birds paused in their flight; all trees and plants burst into bloom, and lotus flowers appeared in every place. Not under the dominion of Mara2 was this beautiful world. But by turning from all its youth, health, and life, to think only of its decrepitude, illness, and death, the Prince Sakya Muni surrounded himself with another world in which Mara had his share of power. I condense here the accounts of his encounters with the Prince, who was on his way to be a hermit.

When the Prince passed out at the palace gates, the king Mara, knowing that the youth was passing beyond his evil power, determined to prevent him. Descending from his abode and floating in the air, Mara cried, ‘Lord, thou art capable of such vast endurance, go not forth to adopt a religious life, but return to thy kingdom, and in seven days thou shalt become an emperor of the world, ruling over the four great continents.’ ‘Take heed, O Mara!’ replied the Prince; ‘I also know that in seven days I might gain universal empire, but I have no desire for such possessions. I know that the pursuit of religion is better than the empire of the world. See how the world is moved, and quakes with praise of this my entry on a religious life! I shall attain the glorious omniscience, and shall teach the wheel of the law, that all teachable beings may free themselves from transmigratory existence. You, thinking only of the lusts of the flesh, would force me to leave all beings to wander without guide into your power. Avaunt! get thee away far from me!’

Mara withdrew, but only to watch for another opportunity. It came when the Prince had reduced himself to emaciation and agony by the severest austerities. Then Mara presented himself, and pretending compassion, said, ‘Beware, O grand Being! Your state is pitiable to look on; you are attenuated beyond measure, and your skin, that was of the colour of gold, is dark and discoloured. You are practising this mortification in vain. I can see that you will not live through it. You, who are a Grand Being, had better give up this course, for be assured you will derive much more advantage from sacrifices of fire and flowers.’ Him the Grand Being indignantly answered, ‘Hearken, thou vile and wicked Mara! Thy words suit not the time. Think not to deceive me, for I heed thee not. Thou mayest mislead those who have no understanding, but I, who have virtue, endurance, and intelligence, who know what is good and what is evil, cannot be so misled. Thou, O Mara! hast eight generals. Thy first is delight in the five lusts of the flesh, which are the pleasures of appearance, sound, scent, flavour, and touch. Thy second general is wrath, who takes the form of vexation, indignation, and desire to injure. Thy third is concupiscence. Thy fourth is desire. Thy fifth is impudence. Thy sixth is arrogance. Thy seventh is doubt. And thine eighth is ingratitude. These are thy generals, who cannot be escaped by those whose hearts are set on honour and wealth. But I know that he who can contend with these thy generals shall escape beyond all sorrow, and enjoy the most glorious happiness. Therefore I have not ceased to practise mortification, knowing that even were I to die whilst thus engaged, it would be a most excellent thing.’

It is added that Mara ‘fled in confusion,’ but the next incident seems to show that his suggestion was not unheeded; for ‘after he had departed,’ the Grand Being had his vision of the three-stringed guitar—one string drawn too tightly, the second too loosely, the third moderately—which last, somewhat in defiance of orchestral ideas, alone gave sweet music, and taught him that moderation was better than excess or laxity. By eating enough he gained that pristine strength and beauty which offended the five Brahmans so that they left him. The third and final effort of Mara immediately preceded the Prince’s attainment of the order of Buddha under the Bo-tree. He now sent his three daughters, Raka (Love), Aradi (Anger), Tanha (Desire). Beautifully bedecked they approached him, and Raka said, ‘Lord, fearest thou not death?’ But he drove her away. The two others also he drove away as they had no charm of sufficient power to entice him. Then Mara assembled his generals, and said, ‘Listen, ye Maras, that know not sorrow! Now shall I make war on the Prince, that man without equal. I dare not attack him in face, but I will circumvent him by approaching on the north side. Assume then all manner of shapes, and use your mightiest powers, that he may flee in terror.’

Having taken on fearful shapes, raising awful sounds, headed by Mara himself, who had assumed immense size, and mounted his elephant Girimaga, a thousand miles in height, they advanced; but they dare not enter beneath the shade of the holy Bo-tree. They frightened away, however, the Lord’s guardian angels, and he was left alone. Then seeing the army approaching from the north, he reflected, ‘Long have I devoted myself to a life of mortification, and now I am alone, without a friend to aid me in this contest. Yet may I escape the Maras, for the virtue of my transcendent merits will be my army.’ ‘Help me,’ he cried, ‘ye thirty Barami! ye powers of accumulated merit, ye powers of Almsgiving, Morality, Relinquishment, Wisdom, Fortitude, Patience, Truth, Determination, Charity, and Equanimity, help me in my fight with Mara!’ The Lord was seated on his jewelled throne (the same that had been formed of the grass on which he sat), and Mara with his army exhausted every resource of terror—monstrous beasts, rain of missiles and burning ashes, gales that blew down mountain peaks—to inspire him with fear; but all in vain! Nay, the burning ashes were changed to flowers as they fell.

‘Come down from thy throne,’ shouted the evil-formed one; ‘come down, or I will cut thine heart into atoms!’ The Lord replied, ‘This jewelled throne was created by the power of my merits, for I am he who will teach all men the remedy for death, who will redeem all beings, and set them free from the sorrows of circling existence.’

Mara then claimed that the throne belonged to himself, and had been created by his own merits; and on this armed himself with the Chakkra, the irresistible weapon of Indra, and Wheel of the Law. Yet Buddha answered, ‘By the thirty virtues of transcendent merits, and the five alms, I have obtained the throne. Thou, in saying that this throne was created by thy merits, tellest an untruth, for indeed there is no throne for a sinful, horrible being such as thou art.’

Then furious Mara hurled the Chakkra, which clove mountains in its course, but could not pass a canopy of flowers which rose over the Lord’s head.

And now the great Being asked Mara for the witnesses of his acts of merit by virtue of which he claimed the throne. In response, Mara’s generals all bore him witness. Then Mara challenged him, ‘Tell me now, where is the man that can bear witness for thee?’ The Lord reflected, ‘Truly here is no man to bear me witness, but I will call on the earth itself, though it has neither spirit nor understanding, and it shall be my witness.’ Stretching forth his hand, he thus invoked the earth: ‘O holy Earth! I who have attained the thirty powers of virtue, and performed the five great alms, each time that I have performed a great act have not failed to pour water on thee. Now that I have no other witness, I call upon thee to give thy testimony!’

The angel of the earth appeared in shape of a lovely woman, and answered, ‘O Being more excellent than angels or men! it is true that, when you performed your great works, you ever poured water on my hair.’ And with these words she wrung her long hair, and from it issued a stream, a torrent, a flood, in which Mara and his hosts were overturned, their insignia destroyed, and King Mara put to flight, amid the loud rejoicings of angels.

Then the evil one and his generals were conquered not only in power but in heart; and Mara, raising his thousand arms, paid reverence, saying, ‘Homage to the Lord, who has subdued his body even as a charioteer breaks his horses to his use! The Lord will become the omniscient Buddha, the Teacher of angels, and Brahmas, and Yakkhas (demons), and men. He will confound all Maras, and rescue men from the whirl of transmigration!’

The menacing powers depicted as assailing Sakya Muni appear only around the infancy of Zoroaster. The interview of the latter with Ahriman hardly amounts to a severe trial, but still the accent of the chief temptation both of Buddha and Christ is in it, namely, the promise of worldly empire. It was on one of those midnight journeys through Heaven and Hell that Zoroaster saw Ahriman, and delivered from his power ‘one who had done both good and evil.’3 When Ahriman met Zoroaster’s gaze, he cried, ‘Quit thou the pure law; cast it to the ground; thou wilt then be in the world all that thou canst desire. Be not anxious about thy end. At least, do not destroy my subjects, O pure Zoroaster, son of Poroscharp, who art born of her thou hast borne!’ Zoroaster answered, ‘Wicked Majesty! it is for thee and thy worshippers that Hell is prepared, but by the mercy of God I shall bury your work with shame and ignominy.’

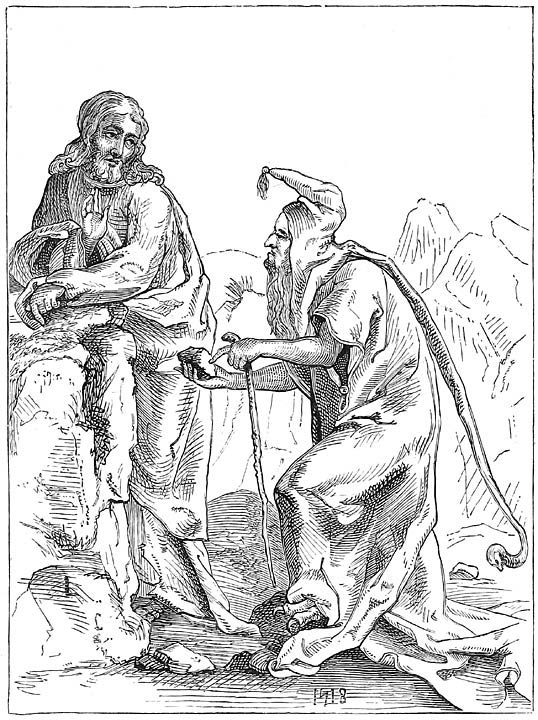

Fig. 6.—Temptation of Christ (Lucas van Leyden).

In the account of Matthew, Satan begins his temptation of Jesus in the same way and amid similar circumstances to those we find in the Siamese legends of Buddha. It occurs in a wilderness, and the appeal is to hunger. The temptation of Buddha, in which Mara promises the empire of the world, is also repeated in the case of Satan and Jesus (Fig. 6). The menaces, however, in this case, are relegated to the infancy, and the lustful temptation is absent altogether. Mark has an allusion to his being in the wilderness forty days ‘with the beasts,’ which may mean that Satan ‘drove’ him into a region of danger to inspire fear. In Luke we have the remarkable claim of Satan that the authority over the world has been delivered to himself, and he gives it to whom he will; which Jesus does not deny, as Buddha did the similar claim of Mara. As in the case of Buddha, the temptation of Jesus ends his fasting; angels bring him food (διηκόνουν ἀυτῶ probably means that), and thenceforth he eats and drinks, to the scandal of the ascetics.

The essential addition in the case of Jesus is the notable temptation to try and perform a crucial act. Satan quotes an accredited messianic prophecy, and invites Jesus to test his claim to be the predicted deliverer by casting himself from the pinnacle of the Temple, and testing the promise that angels should protect the true Son of God. Strauss,4 as it appears to me, has not considered the importance of this in connection with the general situation. ‘Assent,’ he says, ‘cannot be withheld from the canon that, to be credible, the narrative must ascribe nothing to the devil inconsistent with his established cunning. Now, the first temptation, appealing to hunger, we grant, is not ill-conceived; if this were ineffectual, the devil, as an artful tactician, should have had a yet more alluring temptation at hand; but instead of this, we find him, in Matthew, proposing to Jesus the neck-breaking feat of casting himself down from the pinnacle of the Temple—a far less inviting miracle than the metamorphosis of the stones. This proposition finding no acceptance, there follows, as a crowning effort, a suggestion which, whatever might be the bribe, every true Israelite would instantly reject with abhorrence—to fall down and worship the devil.’

Not so! The scapegoat was a perpetual act of worship to the Devil. In this story of the temptation of Christ there enter some characteristic elements of the temptation of Job.5 Uz in the one case and the wilderness in the other mean morally the same, the region ruled over by Azazel. In both cases the trial is under divine direction. And the trial is in both cases to secure a division of worship between the good and evil powers, which was so universal in the East that it was the test of exceptional piety if one did not swerve from an unmixed sacrifice. Jesus is apparently abandoned by the God in whom he trusted; he is ‘driven’ into a wilderness, and there kept with the beasts and without food. The Devil alone comes to him; exhibits his own miraculous power by bearing him through the air to his own Mount Seir, and showing him the whole world in a moment of time; and now says to him, as it were, ‘Try your God! See if he will even turn stones into bread to save his own son, to whom I offer the kingdoms of the world!’ Then bearing him into the ‘holy hill’ of his own God—the pinnacle of the Temple—says, ‘Try now a leap, and see if he saves from being dashed to pieces, even in his own precincts, his so trustful devotee, whom I have borne aloft so safely! Which, then, has the greater power to protect, enrich, advance you,—he who has left you out here to starve, so that you dare not trust yourself to him, or I? Fall down then and worship me as your God, and all the world is yours! It is the world you are to reign over: rule it in my name!

When St. Anthony is tempted by the Devil in the form of a lean monk, it was easy to see that the hermit was troubled with a vision of his own emaciation. When the Devil appears to Luther under guise of a holy monk, it is an obvious explanation that he was impressed by a memory of the holy brothers who still remained in the Church, and who, while they implored his return, pointed out the strength and influence he had lost by secession. Equally simple are the moral elements in the story of Christ’s temptation. While a member of John’s ascetic community, for which ‘though he was rich he became poor,’ hunger, and such anxiety about a living as victimises many a young thinker now, must have assailed him. Later on his Devil meets him on the Temple, quotes scripture, and warns him that his visionary God will not raise him so high in the Church as the Prince of this World can.6 And finally, when dreams of a larger union, including Jews and Gentiles, visited him, the power that might be gained by connivance with universal idolatry would be reflected in the offer of the kingdoms of the world in payment for the purity of his aims and singleness of his worship.

That these trials of self-truthfulness and fidelity, occurring at various phases of life, would be recognised, is certain. A youth of high position, as Christ probably was,7 or even one with that great power over the people which all concede, was, in a worldly sense, ‘throwing away his prospects;’ and this voice, real in its time, would naturally be conventionalised. It would put on the stock costume of devils and angels; and among Jewish christians it would naturally be associated with the forty-days’ fast of Moses (Exod. xxxiv. 28; Deut. ix. 9), and that of Elias (1 Kings xix. 8), and the forty-years’ trial of Israel in the wilderness. Among Greek christians some traces of the legend of Herakles in his seclusion as herdsman, or at the cross-roads between Vice and Virtue, might enter; and it is not impossible that some touches might be added from the Oriental myth which invested Buddha.

However this may be, we may with certainty repair to the common source of all such myths in the higher nature of man, and recognise the power of a pure genius to overcome those temptations to a success unworthy of itself. We may interpret all such legends with a clearness proportioned to the sacrifices we have made for truth and ideal right; and the endless perplexities of commentators and theologians about the impossible outward details of the New Testament story are simple confessions that the great spirit so tried is now made to label with his name his own Tempter—namely, a Church grown powerful and wealthy, which, as the Prince of this World, bribes the conscience and tempts away the talent necessary to the progress of mankind.

1 As given in Mr. Alabaster’s ‘The Wheel of the Law’ (Trübner & Co., 1871). In the Apocryphal Gospels, some of the signs of nature’s joy attending the birth of Buddha are reported at the birth of Mary and that of Christ, as the pausing of birds in their flight, &c. Anna is said to have conceived Mary under a tree, as Maia under a tree brought forth Buddha.

2 ‘Mara, or Man (Sanscrit Màra, death, god of love; by some authors translated ‘illusion,’ as if it came from the Sanscrit Màya), the angels of evil, desire, of love, death, &c. Though King Mara plays the part of our Satan the tempter, he and his host were formerly great givers of alms, which led to their being born in the highest of the Deva heavens, called Paranimit Wasawatti, there to live more than nine thousand million years, surrounded by all the luxuries of sensuality. From this heaven the filthy one, as the Siamese describe him, descends to the earth to tempt and excite to evil.’—Alabaster.

3 Some say Djemschid, others Guenschesp, a warrior sent to hell for beating the fire.

4 Leben Jesu, ii. 54. The close resemblance between the trial of Israel in the wilderness and this of Jesus is drawn in his own masterly way.

5 A passage of the Pesikta (iii. 35) represents a conversation between Jehovah and Satan with reference to Messias which bears a resemblance to the prologue of Job. Satan said: Lord, permit me to tempt Messias and his generation. ‘To him the Lord said: You could have no power over him. Satan again said: Permit me because I have the power. God answered: If you persist longer in this, rather would I destroy thee from the world, than that one soul of the generation of Messias should be lost.’ Though the rabbin might report the trial declined, the Christian would claim it to have been endured.

6 In his fresco of the Temptation at the Vatican, Michael Angelo has painted the Devil in the dress of a priest, standing with Jesus on the Temple.

7 ‘Idols and Ideals.’ London: Trübner & Co. New York: Henry Holt & Co. In the Essay on Christianity I have given my reasons for this belief.

Chapter XVIII.

Trial of the Great.

A ‘Morality’ at Tours—The ‘St. Anthony’ of Spagnoletto—Bunyan’s Pilgrim—Milton on Christ’s Temptation—An Edinburgh saint and Unitarian fiend—A haunted Jewess—Conversion by fever—Limit of courage—Woman and sorcery—Luther and the Devil—The ink-spot at Wartburg—Carlyle’s interpretation—The cowled devil—Carlyle’s trial—In Rue St. Thomas d’Enfer—The Everlasting No—Devil of Vauvert—The latter-day conflict—New conditions—The Victory of Man—The Scholar and the World.

A representation of the Temptation of St. Anthony (marionettes), which I witnessed at Tours (1878), had several points of significance. It was the mediæval ‘Morality’ as diminished by centuries, and conventionalised among those whom the centuries mould in ways and for ends they know not. Amid a scenery of grotesque devils, rudely copied from Callot, St. Anthony appeared, and was tempted in a way that recalled the old pictures. There was the same fair Temptress, in this case the wife of Satan, who warns her lord that his ugly devils will be of no avail against Anthony, and that the whole affair should be confided to her. She being repelled, the rest of the performance consisted in the devils continually ringing the bell of the hermitage, and finally setting fire to it. This conflagration was the supreme torment of Anthony—and, sooth to say, it was a fairly comfortable abode—who utters piteous prayers and is presently comforted by an angel bringing him wreaths of evergreen.

The prayers of the saint and the response of the angel were meant to be seriously taken; but their pathos was generally met with pardonable laughter by the crowd in the booth. Yet there was a pathos about it all, if only this, that the only temptations thought of for a saint were a sound and quiet house and a mistress. The bell-noise alone remained from the great picture of Spagnoletto at Siena, where the unsheltered old man raises his deprecating hand against the disturber, but not his eyes from the book he reads. In Spagnoletto’s picture there are five large books, pen, ink, and hour-glass; but there is neither hermitage to be burnt nor female charms to be resisted.

But Spagnoletto, even in his time, was beholding the vision of exceptional men in the past, whose hunger and thirst was for knowledge, truth, and culture, and who sought these in solitude. Such men have so long left the Church familiar to the French peasantry that any representation of their temptations and trials would be out of place among the marionettes. The bells which now disturb them are those that sound from steeples.

Another picture loomed up before my eyes over the puppet performance at Tours, that which for Bunyan frescoed the walls of Bedford Gaol. There, too, the old demons, giants, and devils took on grave and vast forms, and reflected the trials of the Great Hearts who withstood the Popes and Pagans, the armed political Apollyons and the Giant Despairs, who could make prisons the hermitages of men born to be saviours of the people.

Such were the temptations that Milton knew; from his own heart came the pigments with which he painted the trial of Christ in the wilderness. ‘Set women in his eye,’ said Belial:—

Women, when nothing else, beguiled the heart

Of wisest Solomon, and made him build,

And made him bow to the gods of his wives.

To whom quick answer Satan thus returned.

Belial, in much uneven scale thou weigh’st

All others by thyself....

But he whom we attempt is wiser far

Than Solomon, of more exalted mind,

Made and set wholly on the accomplishment

Of greatest things....

Therefore with manlier objects we must try

His constancy, with such as have more show

Of worth, of honour, glory, and popular praise;

Rocks whereon greatest men have oftest wrecked.1

The progressive ideas which Milton attributed to Satan have not failed. That Celestial City which Bunyan found it so hard to reach has now become a metropolis of wealth and fashion, and the trials which once beset pilgrims toiling towards it are now transferred to those who would pass beyond it to another city, seen from afar, with temples of Reason and palaces of Justice.

The old phantasms have shrunk to puppets. The trials by personal devils are relegated to the regions of insanity and disease. It is everywhere a dance of puppets though on a cerebral stage. A lady well known in Edinburgh related to me a terrible experience she had with the devil. She had invited some of her relations to visit her for some days; but these relatives were Unitarians, and, after they had gone, having entered the room which they had occupied, she was seized by the devil, thrown on the floor, and her back so strained that she had to keep her bed for some time. This was to her ‘the Unitarian fiend’ of which the Wesleyan Hymn-Book sang so long; but even the Wesleyans have now discarded the famous couplet, and there must be few who would not recognise that the old lady at Edinburgh merely had a tottering body representing a failing mind.

I have just read a book in which a lady in America relates her trial by the devil. This lady, in her girlhood, was of a christian family, but she married a rabbi and was baptized into Judaism. After some years of happy life a terrible compunction seized her; she imagined herself lost for ever; she became ill. A christian (Baptist) minister and his wife were the evil stars in her case, and with what terrors they surrounded the poor Jewess may be gathered from the following extract.

‘She then left me—that dear friend left me alone to my God, and to him I carried a lacerated and bleeding heart, and laid it at the foot of the cross, as an atonement for the multiplied sins I had committed, whether of ignorance or wilfulness; and how shall I proceed to portray the heart-felt agonies of that night preceding my deliverance from the shafts of Satan? Oh! this weight, this load of sin, this burden so intolerable that it crushed me to the earth; for this was a dark hour with me—the darkest; and I lay calm, to all appearance, but with cold perspiration drenching me, nor could I close my eyes; and these words again smote my ear, No redemption, no redemption; and the tempter came, inviting me, with all his blandishment and power, to follow him to his court of pleasure. My eyes were open; I certainly saw him, dressed in the most phantastic shape. This was no illusion; for he soon assumed the appearance of one of the gay throng I had mingled with in former days, and beckoned me to follow. I was awake, and seemed to lie on the brink of a chasm, and spirits were dancing around me, and I made some slight outcry, and those dear girls watching with me came to me, and looked at me. They said I looked at them but could not speak, and they moistened my lips, and said I was nearly gone; then I whispered, and they came and looked at me again, but would not disturb me. It was well they did not; for the power of God was over me, and angels were around me, and whispering spirits near, and I whispered in sweet communion with them, as they surrounded me, and, pointing to the throne of grace, said, ‘Behold!’ and I felt that the glory of God was about to manifest itself; for a shout, as if a choir of angels had tuned their golden harps, burst forth in, ‘Glory to God on high,’ and died away in softest strains of melody. I lifted up my eyes to heaven, and there, so near as to be almost within my reach, the brightest vision of our Lord and Saviour stood before me, enveloped with a light, ethereal mist, so bright and yet transparent that his divine figure could be seen distinctly, and my eyes were riveted upon him; for this bright vision seemed to touch my bed, standing at the foot, so near, and he stretched forth his left hand toward me, whilst with the right one he pointed to the throne of grace, and a voice came, saying, ‘Blessed are they who can see God; arise, take up thy cross and follow me; for though thy sins be as scarlet they shall be white as wool.’ And with my eyes fixed on that bright vision, I saw from the hand stretched toward me great drops of blood, as if from each finger; for his blessed hand was spread open, as if in prayer, and those drops fell distinctly, as if upon the earth; and a misty light encircled me, and a voice again said, ‘Take up thy cross and follow me; for though thy sins be as scarlet they shall be white as wool.’ And angels were all around me, and I saw the throne of heaven. And, oh! the sweet calm that stole over my senses. It must have been a foretaste of heavenly bliss. How long I lay after this beautiful vision I know not; but when I opened my eyes it was early dawn, and I felt so happy and well. My young friends pressed around my bedside, to know how I felt, and I said, ‘I am well and so happy.’ They then said I was whispering with some one in my dreams all night. I told them angels were with me; that I was not asleep, and I had sweet communion with them, and would soon be well.’2

That is what the temptation of Jesus in the wilderness comes to when dislocated from its time and place, and, with its gathered ages of fable, is imported at last to be an engine of torture sprung on the nerves of a devout woman. This Jewess was divorced from her husband by her Christianity; her child died a victim to precocious piety; but what were home and affection in ruins compared with salvation from that frightful devil seen in her holy delirium?

History shows that it has always required unusual courage for a human being to confront an enemy believed to be præternatural. This Jewess would probably have been able to face a tiger for the sake of her husband, but not that fantastic devil. Not long ago an English actor was criticised because, in playing Hamlet, he cowered with fear on seeing the ghost, all his sinews and joints seeming to give way; but to me he appeared then the perfect type of what mankind have always been when believing themselves in the presence of præternatural powers. The limit of courage in human nature was passed when the foe was one which no earthly power or weapon could reach.

In old times, nearly all the sorcerers and witches were women; and it may have been, in some part, because woman had more real courage than man unarmed. Sorcery and witchcraft were but the so-called pagan rites in their last degradation, and women were the last to abandon the declining religion, just as they are the last to leave the superstition which has followed it. Their sentiment and affection were intertwined with it, and the threats of eternal torture by devils which frightened men from the old faith to the new were less powerful to shake the faith of women. When pagan priests became christians, priestesses remained, to become sorceresses. The new faith had gradually to win the love of the sex too used to martyrdom on earth to fear it much in hell. And now, again, when knowledge clears away the old terrors, and many men are growing indifferent to all religion, because no longer frightened by it, we may expect the churches to be increasingly kept up by women alone, simply because they went into them more by attraction of saintly ideals than fear of diabolical menaces.

Thomas Carlyle has selected Luther’s boldness in the presence of what he believed the Devil to illustrate his valour. ‘His defiance of the ‘Devils’ in Worms,’ says Carlyle, ‘was not a mere boast, as the like might be if spoken now. It was a faith of Luther’s that there were Devils, spiritual denizens of the Pit, continually besetting men. Many times, in his writings, this turns up; and a most small sneer has been grounded on it by some. In the room of the Wartburg, where he sat translating the Bible, they still show you a black spot on the wall; the strange memorial of one of these conflicts. Luther sat translating one of the Psalms; he was worn down with long labour, with sickness, abstinence from food; there rose before him some hideous indefinable Image, which he took for the Evil One, to forbid his work; Luther started up with fiend-defiance; flung his inkstand at the spectre, and it disappeared! The spot still remains there; a curious monument of several things. Any apothecary’s apprentice can now tell us what we are to think of this apparition, in a scientific sense; but the man’s heart that dare rise defiant, face to face, against Hell itself, can give no higher proof of fearlessness. The thing he will quail before exists not on this earth nor under it—fearless enough! ‘The Devil is aware,’ writes he on one occasion, ‘that this does not proceed out of fear in me. I have seen and defied innumerable Devils. Duke George,’—of Leipzig, a great enemy of his,—‘Duke George is not equal to one Devil,’ far short of a Devil! ‘If I had business at Leipzig, I would ride into Leipzig, though it rained Duke Georges for nine days running.’ What a reservoir of Dukes to ride into!’3

Although Luther’s courage certainly appears in this, it is plain that his Devil was much humanised as compared with the fearful phantoms of an earlier time. Nobody would ever have tried an inkstand on the Gorgons, Furies, Lucifers of ancient belief. In Luther’s Bible the Devil is pictured as a monk—a lean monk, such as he himself was only too likely to become if he continued his rebellion against the Church (Fig. 17). It was against a Devil liable to resistance by physical force that he hurled his inkstand, and against whom he also hurled the contents of his inkstand in those words which Richter said were half-battles.

Luther’s Devil, in fact, represents one of the last phases in the reduction of the Evil Power from a personified phantom with which no man could cope, to that impersonal but all the more real moral obstruction with which every man can cope—if only with an inkstand. The horned monster with cowl, beads, and cross, is a mere transparency, through which every brave heart may recognise the practical power of wrong around him, the established error, disguised as religion, which is able to tempt and threaten him.

The temptations with menace described—those which, coming upon the weak nerves of women, vanquished their reason and heart; that which, in a healthy man, raised valour and power—may be taken as side-lights for a corresponding experience in the life of a great man now living—Carlyle himself. It was at a period of youth when, amid the lonely hills of Scotland, he wandered out of harmony with the world in which he lived. Consecrated by pious parents to the ministry, he had inwardly renounced every dogma of the Church. With genius and culture for high work, the world demanded of him low work. Friendless, alone, poor, he sat eating his heart, probably with little else to eat. Every Scotch parson he met unconsciously propounded to that youth the question whether he could convert his heretical stone into bread, or precipitate himself from the pinnacle of the Scotch Kirk without bruises? Then it was he roamed in his mystical wilderness, until he found himself in the gayest capital of the world, which, however, on him had little to bestow but a further sense of loneliness.

‘Now, when I look back, it was a strange isolation I then lived in. The men and women around me, even speaking with me, were but Figures; I had practically forgotten that they were alive, that they were not merely automatic. In the midst of their crowded streets and assemblages, I walked solitary; and (except as it was my own heart, not another’s, that I kept devouring) savage also, as is the tiger in his jungle. Some comfort it would have been, could I, like a Faust, have fancied myself tempted and tormented of a Devil; for a Hell, as I imagine, without Life, though only diabolic Life, were more frightful: but in our age of Downpulling and Disbelief, the very Devil has been pulled down—you cannot so much as believe in a Devil. To me the Universe was all void of Life, of Purpose, of Volition, even of Hostility: it was one huge, dead, immeasurable, Steam-engine, rolling on, in its dead indifference, to grind me limb from limb. Oh, the vast gloomy, solitary Golgotha, and Mill of Death! Why was the Living banished thither, companionless, conscious? Why, if there is no Devil; nay, unless the Devil is your God?’ ...

‘From suicide a certain aftershine of Christianity withheld me.’ ...

‘So had it lasted, as in bitter, protracted Death-agony, through long years. The heart within me, unvisited by any heavenly dewdrop, was smouldering in sulphurous, slow-consuming fire. Almost since earliest memory I had shed no tear; or once only when I, murmuring half-audibly, recited Faust’s Deathsong, that wild Selig der den er im Siegesglanze findet (Happy whom he finds in Battle’s splendour), and thought that of this last Friend even I was not forsaken, that Destiny itself could not doom me not to die. Having no hope, neither had I any definite fear, were it of Man or of Devil; nay, I often felt as if it might be solacing could the Arch-Devil himself, though in Tartarean terrors, rise to me that I might tell him a little of my mind. And yet, strangely enough, I lived in a continual, indefinite, pining fear; tremulous, pusillanimous, apprehensive of I knew not what; it seemed as if all things in the Heavens above and the Earth beneath would hurt me; as if the Heavens and the Earth were but boundless jaws of a devouring monster, wherein I, palpitating, waited to be devoured.

‘Full of such humour, and perhaps the miserablest man in the whole French Capital or Suburbs, was I, one sultry Dogday, after much perambulation, toiling along the dirty little Rue Sainte Thomas de l’Enfer, among civic rubbish enough, in a close atmosphere, and over pavements hot as Nebuchadnezzar’s Furnace; whereby doubtless my spirits were little cheered; when all at once there rose a Thought in me, and I asked myself, ‘What art thou afraid of? Wherefore, like a coward, dost thou for ever pip and whimper, and go cowering and trembling? Despicable biped! what is the sum-total of the worst that lies before thee? Death? Well, Death; and say the pangs of Tophet too, and all that the Devil or Man may, will, or can do against thee! Hast thou not a heart; canst thou not suffer whatsoever it be; and, as a Child of Freedom, though outcast, trample Tophet itself under thy feet, while it consumes thee! Let it come, then; I will meet it and defy it!’ And as I so thought, there rushed like a stream of fire over my whole soul; and I shook base Fear away from me for ever. I was strong, of unknown strength; a spirit, almost a god. Ever from that time the temper of my misery was changed: not Fear or whining Sorrow was it, but Indignation and grim fire-eyed Defiance.

‘Thus had the Everlasting No pealed authoritatively through all the recesses of my Being, of my Me; and then was it that my whole Me stood up, in native God-created majesty and with emphasis recorded its Protest. Such a Protest, the most important transaction in Life, may that same Indignation and Defiance, in a psychological point of view, be fitly called. The Everlasting No had said, ‘Behold thou art fatherless, outcast, and the Universe is mine (the Devil’s);’ to which my whole Me now made answer, ‘I am not thine, but Free, and for ever hate thee!’

‘It is from this hour that I incline to date my spiritual New Birth, or Baphometic fire-baptism; perhaps I directly thereupon began to be a Man.’4

Perhaps he who so uttered his Apage Satana did not recognise amid what haunted Edom he wrestled with his Phantom. Saint Louis, having invited the Carthusian monks to Paris, assigned them a habitation in the Faubourg Saint-Jacques, near the ancient chateau of Vauvert, a manor built by Robert (le Diable), but for a long time then uninhabited, because infested by demons, which had, perhaps, been false coiners. Fearful howls had been heard there, and spectres seen, dragging chains; and, in particular, it was frequented by a fearful green monster, serpent and man in one, with a long white beard, wielding a huge club, with which he threatened all who passed that way. This demon, in common belief, passed along the road to and from the chateau in a fiery chariot, and twisted the neck of every human being met on his way. He was called the Devil of Vauvert. The Carthusians were not frightened by these stories, but asked Louis to give them the Manor, which he did, with all its dependencies. After that nothing more was heard of the Diable Vauvert or his imps. It was but fair to the Demons who had assisted the friars in obtaining a valuable property so cheaply that the street should thenceforth bear the name of Rue d’Enfer, as it does. But the formidable genii of the place haunted it still, and, in the course of time, the Carthusians proved that they could use with effect all the terrors which the Devils had left behind them. They represented a great money-coining Christendom with which free-thinking Michaels had to contend, even to the day when, as we have just read, one of the bravest of these there encountered his Vauvert devil and laid him low for ever.

I well remember that wretched street of St. Thomas leading into Hell Street, as if the Parisian authorities, remembering that Thomas was a doubter, meant to remind the wayfarer that whoso doubteth is damned. Near by is the convent of St. Michael, who makes no war on the neighbouring Rue Dragon. All names—mere idle names! Among the thousands that crowd along them, how many pause to note the quaintness of the names on the street-lamps, remaining there from fossil fears and phantom battles long turned to fairy lore. Yet amid them, on that sultry day, in one heart, was fought and won a battle which summed up all their sense and value. Every Hell was conquered then and there when Fear was conquered. There, when the lower Self was cast down beneath the poised spear of a Free Mind, St. Michael at last chained his dragon. There Luther’s inkstand was not only hurled, but hit its mark; there, ‘Get thee behind me,’ was said, and obeyed; there Buddha brought the archfiend Mara to kneel at his feet.

And it was by sole might of a Man. Therefore may this be emphasised as the temptation and triumph which have for us to-day the meaning of all others.

A young man of intellectual power, seeing beyond all the conventional errors around him, without means, feeling that ordinary work, however honourable, would for him mean failure of his life—because failure to contribute his larger truth to mankind—he finds the terrible cost of his aim to be hunger, want, a life passed amid suspicion and alienation, without sympathy, lonely, unloved—and, alas! with a probability that all these losses may involve loss of just what they are incurred for, the power to make good his truth. After giving up love and joy, he may, after all, be unable to give living service to his truth, but only a broken body and shed blood. Similar trials in outer form have been encountered again and again; not only in the great temptations and triumphs of sacred tradition, but perhaps even more genuinely in the unknown lives of many pious people all over the world, have hunger, want, suffering, been conquered by faith. But rarely amid doubts. Rarely in the way of Saint Thomas, in no fear of hell or devil, nor in any hope of reward in heaven, or on earth; rarely indeed without any feeling of a God taking notice, or belief in angels waiting near, have men or women triumphed utterly over self. All history proves what man can sacrifice on earth for an eternal weight of glory above. We know how cheerfully men and women can sing at the stake, when they feel the fire consuming them to be a chariot bearing them to heaven. We understand the valour of Luther marching against his devils with his hymn, ‘Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott.’ But it is important to know what man’s high heart is capable of without any of these encouragements or aids, what man’s moral force when he feels himself alone. For this must become an increasingly momentous consideration.

Already the educated youth of our time have followed the wanderer of threescore years ago into that St. Thomas d’Enfer Street, which may be morally translated as the point where man doubts every hell he does not feel, and every creed he cannot prove. The old fears and hopes are fading faster from the minds around us than from their professions. There must be very few sane people now who are restrained by fear of hell, or promises of future reward. What then controls human passion and selfishness? For many, custom; for others, hereditary good nature and good sense; for some, a sense of honour; for multitudes, the fear of law and penalties. It is very difficult indeed, amid these complex motives, to know how far simple human nature, acting at its best, is capable of heroic endurance for truth, and of pure passion for the right. This cannot be seen in those who intellectually reject the creed of the majority, but conform to its standards and pursue its worldly advantages. It must be seen, if at all, in those who are radically severed from the conventional aims of the world,—who seek not its wealth, nor its honours, decline its proudest titles, defy its authority, share not its prospects for time or eternity. It must be proved by those, the grandeur of whose aims can change the splendours of Paris to a wilderness. These may show what man, as man, is capable of, what may be his new birth, and the religion of his simple manhood. What they think, say, and do is not prescribed either by human or supernatural command; in them you do not see what society thinks, or sects believe, or what the populace applaud. You see the individual man building his moral edifice, as genuinely as birds their nests, by law of his own moral constitution. It is a great thing to know what those edifices are, for so at last every man will have to build if he build at all. And if noble lives cannot be so lived, we may be sure the career of the human race will be downhill henceforth. For any unbiassed mind may judge whether the tendency of thought and power lies toward or away from the old hopes and fears on which the regime of the past was founded.

A great and wise Teacher of our time, who shared with Carlyle his lonely pilgrimage, has admonished his generation of the temptations brought by talent,—selfish use of it for ambitious ends on the one hand, or withdrawal into fruitless solitude on the other; and I cannot forbear closing this chapter with his admonition to his young countrymen forty years ago.5

‘Public and private avarice makes the air we breathe thick and fat. The scholar is decent, indolent, complacent. See already the tragic consequence. The mind of this country, taught to aim at low objects, eats upon itself. There is no work for any but the decorous and the complacent. Young men of the fairest promise, who begin life upon our shores, inflated by the mountain winds, shined upon by all the stars of God, find the earth below not in unison with these,—but are hindered from action by the disgust which the principles on which business is managed inspire and turn drudges, or die of disgust,—some of them suicides. What is the remedy? They did not yet see, and thousands of young men as hopeful, now crowding to the barriers for the career, do not yet see, that if the single man plant himself indomitably on his instincts, and there abide, the huge world will come round to him. Patience—patience;—with the shades of all the good and great for company; and for solace, the perspective of your own infinite life; and for work, the study and the communication of principles, the making those instincts prevalent, the conversion of the world. Is it not the chief disgrace in the world—not to be an unit; not to be reckoned one character; not to yield that peculiar fruit which each man was created to bear,—but to be reckoned in the gross, in the hundred, in the thousand of the party, the section, to which we belong; and our opinion predicted geographically, as the north or the south? Not so, brothers and friends,—please God, ours shall not be so. We will walk on our own feet; we will work with our own hands; we will speak our own minds.’

1 ‘Paradise Regained,’ ii.

2 ‘Henry Luria; or, the Little Jewish Convert: being contained in the Memoir of Mrs. S. T. Cohen, relict of the Rev. Dr. A. H. Cohen, late Rabbi of the Synagogue in Richmond, Va.’ 1860.

3 ‘Heroes and Hero-worship,’ iv.

4 ‘Sartor Resartus.’ London: Chapman & Hall, 1869, p. 160.

5 ‘The American Scholar.’ An Oration delivered before the Phi Beta Kappa Society at Cambridge (Massachusetts), August 31, 1837. By Ralph Waldo Emerson.