Chapter XXI.

Antichrist.

The Kali Age—Satan sifting Simon—Satan as Angel of Light—Epithets of Antichrist—The Cæsars—Nero—Sacraments imitated by Pagans—Satanic signs and wonders—Jerome on Antichrist—Armillus—Al Dajjail—Luther on Mohammed—‘Mawmet’—Satan ‘God’s ape’—Mediæval notions—Witches Sabbath—An Infernal Trinity—Serpent of Sins—Antichrist Popes—Luther as Antichrist—Modern notions of Antichrist.

In the ‘Padma Purana’ it is recorded that when King Vena embraced heretical doctrine and abjured the temples and sacrifices, the people following him, seven powerful Rishis, high priests, visited him and entreated him to return to their faith. They said, ‘These acts, O king, which thou art performing, are not of our holy traditions, nor fit for our religion, but are such as shall be performed by mankind at the entrance of Kali, the last and sinful age, when thy new faith shall be received by all, and the service of the gods be utterly relinquished.’ King Vena, being thus in advance of his time, was burned on the sacred grass, while a mantra was performed for him.

This theory of Kali is curious as indicating a final triumph of the enemies of the gods. In the Scandinavian theory of ‘Ragnarok,’ the Twilight of the gods, there also seems to have been included no hope of the future victory of the existing gods. In the Parsí faith we first meet with the belief in a general catastrophe followed by the supremacy and universal sway of good. This faith characterised the later Hebrew prophecies, and is the spirit of Paul’s brave saying, ‘When all things shall be subjected unto him, then also shall the Son himself be subject unto him that put all things under him, that God may be all in all.’

When, however, theology and metaphysics advanced and modelled this fiery lava of prophetic and apostolic ages into dogmatic shapes, evil was accorded an equal duration with good. The conflict between Christ and his foes was not to end with the conversion or destruction of his foes, but his final coming as monarch of the world was to witness the chaining up of the Archfiend in the Pit.

Christ’s own idea of Satan, assuming certain reported expressions to have been really uttered by him, must have been that which regarded him as a Tempter to evil, whose object was to test the reality of faith. ‘Simon, Simon, behold, Satan asked you for himself, that he might sift you as the wheat; but I made supplication for thee, that thy faith fail not; and when once thou hast returned, confirm thy brethren. And he said unto him, Lord, I am ready to go with thee, both into prison and into death. And he said, I tell thee, Peter, a cock will not crow this day till thou wilt thrice deny that thou knowest me.’1 Such a sentiment could not convey to Jewish ears a degraded notion of Satan, except as being a nocturnal spirit who must cease his work at cock-crow. It is an adaptation of what Jehovah himself was said to do, in the prophecy of Amos. ‘I will not utterly destroy the house of Jacob, saith the Lord.... I will sift the house of Israel among all nations, like as corn is sifted in a sieve, yet shall not the least grain fall upon the earth.’2

Paul, too, appears to have had some such conception of Satan, since he speaks of an evil-doer as delivered up to Satan ‘for the destruction of the flesh that the spirit may be saved.’3 There is, however, in another passage an indication of the distinctness with which Paul and his friends had conceived a fresh adaptation of Satan as obstacle of their work. ‘For such,’ he says, ‘are false apostles, deceitful workers, transforming themselves into apostles of Christ. And no marvel: for Satan transforms himself into an angel of light. It is no great thing therefore if his ministers also transform themselves as ministers of righteousness; whose end will be according to their works.’4 It may be noted here that Paul does not think of Satan himself as transforming himself to a minister of righteousness, but of Satan’s ministers as doing so. It is one of a number of phrases in the New Testament which reveal the working of a new movement towards an expression of its own. Real and far-reaching religious revolutions in history are distinguished from mere sectarian modifications, which they sum up in nothing more than in their new phraseology. When Jehovah, Messias, and Satan are gradually supplanted by Father, Christ, and Antichrist (or Man of Sin, False Christ, Withholder (κατέχον), False Prophet, Son of Perdition, Mystery of Iniquity, Lawless One), it is plain that new elements are present, and new emergencies. These varied phrases just quoted could not, indeed, crystallise for a long time into any single name for the new Obstacle to the new life, for during the same time the new life itself was too living, too various, to harden in any definite shape or be marked with any special name. The only New Testament writer who uses the word Antichrist is the so-called Apostle John; and it is interesting to remark that it is by him connected with a dogmatic statement of the nature of Christ and definition of heresy. ‘Every spirit that confesses Jesus Christ is come in the flesh is of God; and every spirit that confesses not Jesus is not of God: and this is the spirit of Antichrist, whereof ye have heard that it comes; and now it is in the world already.’5 This language, characteristic of the middle and close of the second century,6 is in strong contrast with Paul’s utterance in the first century, describing the Man of Sin (or of lawlessness, the son of perdition), as one ‘who opposeth and exalteth himself above all that is called God, or that is worshipped; so that he sat in the temple of God, showing himself that he is God.’7 Christ has not yet begun to supplant God; to Paul he is the Son of God confronting the Son of Destruction, the divine man opposed by the man of sin. When the nature of Christ becomes the basis of a dogma, the man of sin is at once defined as the opponent of that dogma.

As this dogma struggled on to its consummation and victory, it necessarily took the form of a triumph over the Cæsars, who were proclaiming themselves gods, and demanding worship as such. The writer of the second Epistle bearing Peter’s name saw those christians who yielded to such authority typified in Balaam, the erring prophet who was opposed by the angel;8 the writer of the Gospel of John saw the traitor Judas as the ‘son of perdition,’9 representing Jesus as praying that the rest of his disciples might be kept ‘out of the evil one;’ and many similar expressions disclose the fact that, towards the close of the second century, and throughout the third, the chief obstacle of those who were just beginning to be called ‘Christians’ was the temptation offered by Rome to the christians themselves to betray their sect. It was still a danger to name the very imperial gods who successively set themselves up to be worshipped at Rome, but the pointing of the phrases is unmistakable long before the last of the pagan emperors held the stirrup for the first christian Pontiff to mount his horse.

Nero had answered to the portrait of ‘the son of perdition sitting in the temple of God’ perfectly. He aspired to the title ‘King of the Jews.’ He solemnly assumed the name of Jupiter. He had his temples and his priests, and shared divine honours with his mistress Poppæa. Yet, when Nero and his glory had perished under those phials of wrath described in the Apocalypse, a more exact image of the insidious ‘False Christ’ appeared in Vespasian. His alleged miracles (‘lying wonders’), and the reported prediction of his greatness by a prophet on Mount Carmel, his oppression of the Jews, who had to contribute the annual double drachma to support the temples and gods which Vespasian had restored, altogether made this decorous and popular emperor a more formidable enemy than the ‘Beast’ Nero whom he succeeded. The virtues and philosophy of Marcus Aurelius still increased the danger. Political conditions favoured all those who were inclined to compromise, and to mingle the popular pagan and the Jewish festivals, symbols, and ceremonies. In apocalyptic metaphor, Vespasian and Aurelius are the two horns of the Lamb who spake like the Dragon, i.e., Nero (Rev. xiii. 11).

The beginnings of that mongrel of superstitions which at last gained the name of Christianity were in the liberation, by decay of parts and particles, of all those systems which Julius Cæsar had caged together for mutual destruction. ‘With new thrones rise new altars,’ says Byron’s Sardanapalus; but it is still more true that, with new thrones all altars crumble a little. At an early period the differences between the believers in Christ and those they called idolaters were mainly in name; and, with the increase of Gentile converts, the adoption of the symbolism and practices of the old religions was so universal that the quarrel was about originality. ‘The Devil,’ says Tertullian, ‘whose business it is to pervert the truth, mimics the exact circumstances of the Divine Sacraments in the mysteries of idols. He himself baptizes some, that is to say, his believers and followers: he promises forgiveness of sins from the sacred fount, and thus initiates them into the religion of Mithras; he thus marks on the forehead his own soldiers: he then celebrates the oblation of bread; he brings in the symbol of resurrection, and wins the crown with the sword.’10

What masses of fantastic nonsense it was possible to cram into one brain was shown in the time of Nero, the brain being that of Simon the Magician. Simon was, after all, a representative man; he reappears in christian Gnosticism, and Peter, who denounced him, reappears also in the phrenzy of Montanism. Take the followers of this Sorcerer worshipping his image in the likeness of Jupiter, the Moon, and Minerva; and Montanus with his wild women Priscilla and Maximilla going about claiming to be inspired by the Holy Ghost to re-establish Syrian orthodoxy and asceticism; and we have fair specimens of the parties that glared at each other, and apostrophised each other as children of Belial. They competed with each other by pretended miracles. They both claimed the name of Christ, and all the approved symbols and sacraments. The triumph of one party turned the other into Antichrist.

Thus in process of time, as one hydra-head fell only to be followed by another, there was defined a Spirit common to and working through them all—a new devil, whose special office was hostility to Christ, and whose operations were through those who claimed to be christians as well as through open enemies.

As usual, when the phrases, born of real struggles, had lost their meaning, they were handed up to the theologians to be made into perpetual dogmas. Out of an immeasurable mass of theories and speculations, we may regard the following passage from Jerome as showing what had become the prevailing belief at the beginning of the fifth century. ‘Let us say that which all ecclesiastical writers have handed down, viz., that at the end of the world, when the Roman Empire is to be destroyed, there will be ten kings, who will divide the Roman world among them; and there will arise an eleventh little king who will subdue three of the ten kings, that is, the king of Egypt, of Africa, and of Ethiopia; and on these having been slain, the seven other kings will submit.’ ‘And behold,’ he says, ‘in the ram were the eyes of a man’—this is that we may not suppose him to be a devil or a dæmon, as some have thought, but a man in whom Satan will dwell utterly and bodily—‘and a mouth speaking great things;’ for he is the ‘man of sin, the son of perdition, who sitteth in the temple of God making himself as God.’11

The ‘Little Horn’ of Daniel has proved a cornucopia of Antichrists. Not only the christians but the Jews and the mussulmans have definite beliefs on the subject. The rabbinical name for Antichrist is Armillus, a word found in the Targum (Isa. xi. 4): ‘By the word of his mouth the wicked Armillus shall die.’ There will be twelve signs of the Messiah’s coming—appearance of three apostate kings, terrible heat of the sun, dew of blood, healing dew, the sun darkened for thirty days, universal power of Rome with affliction for Jews, and the appearance of the first Messias (Joseph’s tribe), Nehemiah. The next and seventh sign will be the appearance of Armillus, born of a marble statue in a church at Rome. The Romans will accept him as their god, and the whole world be subject to him. Nehemiah alone will refuse to worship him, and for this will be slain, and the Jews suffer terrible things. The eighth sign will be the appearance of the angel Michael with three blasts of his trumpet—which shall call forth Elias, the forerunner, and the true Messias (Ben David), and bring on the war with Armillus who shall perish, and all christians with him. The ten tribes shall be gathered into Paradise. Messias shall wed the fairest daughter of their race, and when he dies his sons shall succeed him, and reign in unbroken line over a beatified Israel.

The mussulman modification of the notion of Antichrist is very remarkable. They call him Al Dajjail, that is, the impostor. They say that Mohammed told his follower Tamisri Al-Dari, that at the end of the world Antichrist would enter Jerusalem seated on an ass; but that Jesus will then make his second coming to encounter him. The Beast of the Apocalypse will aid Antichrist, but Jesus will be joined by Imam Mahadi, who has never died; together they will subdue Antichrist, and thereafter the mussulmans and christians will for ever be united in one religion. The Jews, however, will regard Antichrist as their expected Messias. Antichrist will be blind of one eye, and deaf of one ear. ‘Unbeliever’ will be written on his forehead. In that day the sun will rise in the west.12

The christians poorly requited this amicable theory of the mussulmans by very extensively identifying Mohammed as Antichrist, at one period. From that period came the English word mawmet (idol), and mummery (idolatry), both of which, probably, are derived from the name of the Arabian Prophet. Daniel’s ‘Little Horn’ betokens, according to Martin Luther, Mohammed. ‘But what are the Little Horn’s Eyes? The Little Horn’s Eyes,’ says he, ‘mean Mohammed’s Alkoran, or Law, wherewith he ruleth. In the which Law there is nought but sheer human reason (eitel menschliche Vernunft).’ ... ‘For his Law,’ he reiterates, ‘teaches nothing but that which human understanding and reason may well like.’ ... Wherefore ‘Christ will come upon him with fire and brimstone.’ When he wrote this—in his ‘army sermon’ against the Turks—in 1529, he had never seen a Koran. ‘Brother Richard’s’ (Predigerordens) Confutatio Alcoran, dated 1300, formed the exclusive basis of his argument. But in Lent of 1540, he relates, a Latin translation, though a very unsatisfactory one, fell into his hands, and once more he returned to Brother Richard, and did his Refutation into German, supplementing his version with brief but racy notes. This Brother Richard had, according to his own account, gone in quest of knowledge to ‘Babylon, that beautiful city of the Saracens,’ and at Babylon he had learnt Arabic and been inured in the evil ways of the Saracens. When he had safely returned to his native land he set about combating the same. And this is his exordium:—‘At the time of the Emperor Heraclius there arose a man, yea, a Devil, and a first-born child of Satan, ... who wallowed in ... and he was dealing in the Black Art, and his name it was Machumet.’ ... This work Luther made known to his countrymen by translating and commenting, prefacing, and rounding it off by an epilogue. True, his notes amount to little more but an occasional ‘Oh fie, for shame, you horrid Devil, you damned Mahomet,’ or ‘O Satan, Satan, you shall pay for that,’ or, ‘That’s it, Devils, Saracens, Turks, it’s all the same,’ or, ‘Here the Devil smells a rat,’ or briefly, ‘O Pfui Dich, Teufel!’ except when he modestly, with a query, suggests whether those Assassins, who, according to his text, are regularly educated to go out into the world in order to kill and slay all Worldly Powers, may not, perchance, be the Gypsies or the ‘Tattern’ (Tartars); or when he breaks down with a ‘Hic nescio quid dicat translator.’ His epilogue, however, is devoted to a special disquisition as to whether Mohammed or the Pope be worse. And in the twenty-second chapter of this disquisition he has arrived at the final conclusion that, after all, the Pope is worse, and that he, and not Mohammed, is the real ‘Endechrist.’ ‘Wohlen,’ he winds up, ‘God grant us his grace, and punish both the Pope and Mohammed, together with their devils. I have done my part as a true prophet and teacher. Those who won’t listen may leave it alone.’ In similar strains speaks the learned and gentle Melancthon. In an introductory epistle to a reprint of that same Latin Koran which displeased Luther so much, he finds fault with Mohammed, or rather, to use his own words, he thinks that ‘Mohammed is inspired by Satan,’ because he ‘does not explain what sin is,’ and further, since he ‘showeth not the reason of human misery.’ He agrees with Luther about the Little Horn: though in another treatise he is rather inclined to see in Mohammed both Gog and Magog. And ‘Mohammed’s sect,’ he says, ‘is altogether made up (conflata) of blasphemy, robbery, and shameful lusts.’ Nor does it matter in the least what the Koran is all about. ‘Even if there were anything less scurrilous in the book, it need not concern us any more than the portents of the Egyptians, who invoked snakes and cats.... Were it not that partly this Mohammedan pest, and partly the Pope’s idolatry, have long been leading us straight to wreck and ruin—may God have mercy upon some of us!’13

‘Mawmet’ was used by Wicliffe for idol in his translation of the New Testament, Acts vii. 41, ‘And they made a calf in those days and offered a sacrifice to the Mawmet’ (idol). The word, though otherwise derived by some, is probably a corruption of Mohammed. In the ‘Mappa Mundi’ of the thirteenth century we find the representation of the golden calf in the promontory of Sinai, with the superscription ‘Mahum’ for Mohammed, whose name under various corruptions, such as Mahound, Mawmet, &c., became a general byword in the mediæval languages for an idol. In a missionary hymn of Wesley’s Mohammed is apostrophised as—

That Arab thief, as Satan bold,

Who quite destroyed Thy Asian fold;

and the Almighty is adjured to—

The Unitarian fiend expel,

And chase his doctrine back to Hell.

In these days, when the very mention of the Devil raises a smile, we can hardly realise the solemnity with which his work was once viewed. When Goethe represents Mephistopheles as undertaking to teach Faust’s class in theology and dwells on his orthodoxy, it is the refrain of the faith of many generations. The Devil was not ‘God’s Ape,’ as Tertullian called him, in any comical way; not only was his ceremonial believed to be modelled on that of God, but his inspiration of his followers was believed to be quite as potent and earnest. Tertullian was constrained to write in this strain—‘Blush, my Roman fellow-soldiers, even if ye are not to be judged by Christ, but by any soldier of Mithras, who when he is undergoing initiation in the cave, the very camp of the Powers of Darkness, when the wreath is offered him (a sword being placed between as if in semblance of martyrdom), and then about to be set on his head, he is warned to put forth his hand and push the wreath away, transferring it to, perchance, his shoulder, saying at the same time, My only crown is Mithras. And thenceforth he never wears a wreath; and this is a mark he has for a test, whenever tried as to his initiation, for he is immediately proved to be a soldier of Mithras if he throws down the wreath offered him, saying his crown is in his god. Let us therefore acknowledge the craft of the Devil, who mimics certain things of those that be divine, in order that he may confound and judge us by the faith of his own followers.’

This was written before the exaltation of Christianity under Constantine. When the age of the martyrdom of the so-called pagans came on, these formulæ became real, and the christians were still more confounded by finding that the worshippers of the Devil, as they thought them, could yield up their lives in many parts of Europe as bravely for their faith as any christian had ever done. The ‘Prince of this world’ became thus an unmeaning phrase except for the heretics. Christ had become the Prince of this world; and he was opposed by religious devotees as earnest as any who had suffered under Nero. The relation of the Opposition to the Devil was yet more closely defined when it claimed the christian name for its schism or heresy, and when it carried its loyalty to the Adversary of the Church to the extent of suffering martyrdom. ‘Tell me, holy father,’ said Evervinus to St. Bernard, concerning the Albigenses, ‘how is this? They entered to the stake and bore the torment of the fire not only with patience, but with joy and gladness. I wish your explanation, how these members of the Devil could persist in their heresy with a courage and constancy scarcely to be found in the most religious of the faith of Christ?’

Under these circumstances the personification of Antichrist had a natural but still wonderful development. He was to be born of a virgin, in Babylon, to be educated at Bethsaida and Chorazin, and to make a triumphal entry into Jerusalem, proclaiming himself the Son of God. In the interview at Messina (1202) between Richard I. and the Abbot Joachim of Floris, the king said, ‘I thought that Antichrist would be born at Antioch or in Babylon, and of the tribe of Dan, and would reign in the temple of the Lord in Jerusalem, and would walk in that land in which Christ walked, and would reign in it for three years and a half, and would dispute against Elijah and Enoch, and would kill them, and would afterwards die; and that after his death God would give sixty days of repentance, in which those might repent which should have erred from the way of truth, and have been seduced by the preaching of Antichrist and his false prophets.’

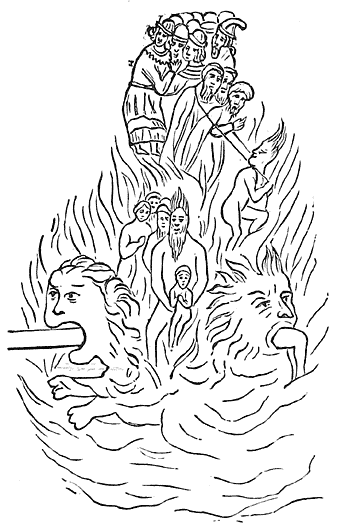

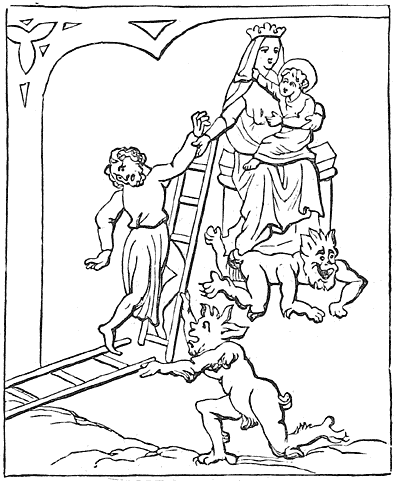

Fig 9.—Procession of the Serpent of Sins.

This belief was reflected in Western Europe in the belief that the congregation of Witches assembled on their Sabbath (an institution then included among paganisms) to celebrate grand mass to the Devil, and that all the primitive temples were raised in honour of Satan. In the Russian Church the correspondence between the good and evil powers, following their primitive faith in the conflict between Byelbog and Tchernibog (white god and black god), went to the curious extent of picturing in hell a sort of infernal Trinity. The Father throned in Heaven with the Son between his knees and the Dove beside or beneath him, was replied to by a majestic Satan in hell, holding his Son (Judas) on his knees, and the Serpent acting as counteragent of the Dove. This singular arrangement may still be seen in many of the pictures which cover the walls of the oldest Russian churches (Fig. 9). The infernal god is not without a solemn majesty answering to that of his great antagonist above. The Serpent of Sins proceeds from the diabolical Father and Son, passing from beneath their throne through one of the two mouths of Hell, and then winds upward, hungrily opening its jaws near the terrible Balances where souls are weighed (Fig. 10). Along its hideous length are seated at regular intervals nine winged devils, representing probably antagonists of the nine Sephiroth or Æons of the Gnostic theology. Each is armed with a hook whereby the souls weighed and found wanting may be dragged. The sins which these devils represent are labelled, generally on rings around the serpent, and increase in heinousness towards the head. It is a curious fact that the Sin nearest the head is marked ‘Unmercifulness.’ Strange and unconscious sarcasm on an Omnipotent Deity under whose sway exists this elaboration of a scheme of sins and tortures precisely corresponding to the scheme of virtues and joys!

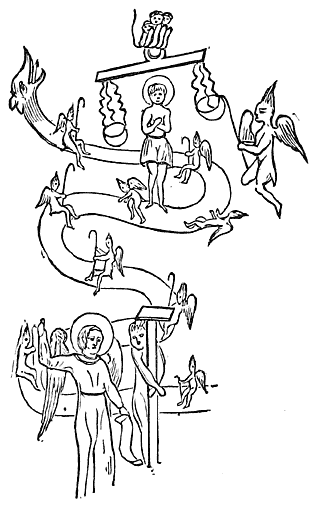

Fig. 10.—Ancient Russian Wall-Painting.

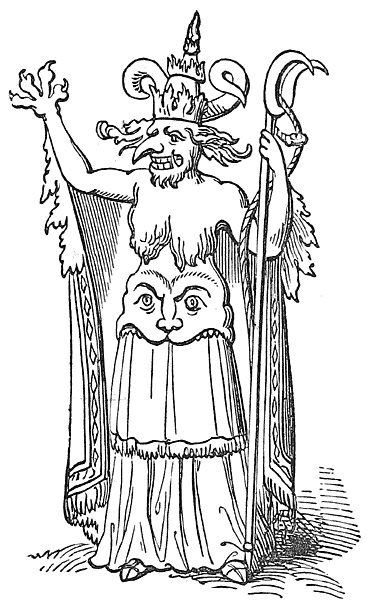

Fig. 11.—Alexander VI. as Antichrist.

Truly said the Epistle of John, there be many Antichrists. If this was true before the word Christianity had been formed, or the system it names, what was the case afterwards? For centuries we find vast systems denouncing each other as Antichrist. And ultimately, as a subtle hardly-conscious heresy spread abroad, the great excommunicator of antichrists itself, Rome, acquired that title, which it has never shaken off since. The See of Rome did not first receive that appellation from Protestants, but from its own chiefs. Gregory himself (A.C. 590) started the idea by declaring that any man who held even the shadow of such power as the Popes arrogated to themselves after his time would be the forerunner of Antichrist. Arnulphus, Bishop of Orleans, in an invective against John XV. at Rheims (A.C. 991), intimated that a Pope destitute of charity was Antichrist. But the stigma was at length fixed (twelfth century) by Amalrich of Bena (‘Quia Papa esset Antichristus et Roma Babylon et ipse sedit in Monte Oliveti, i.e., in pinguedine potestatis’); and also by the Abbot Joachim (A.C. 1202). The theory of Richard I., as stated to Joachim concerning Antichrist, has already been quoted. It was in the presence of the Archbishops of Rouen and Auxerre, and the Bishop of Bayonne, and represented their opinion and the common belief of the time. But Joachim said the Second Apocalyptic Beast represented some great prelate who will be like Simon Magus, and, as it were, universal Pontiff, and that very Antichrist of whom St. Paul speaks. Hildebrand was the first Pope to whom this ugly label was affixed, but the career of Alexander VI. (Roderic Borgia) made it for ever irremovable for the Protestant mind. There is in the British Museum a volume of caricatures, dated 1545, in which occurs an ingenious representation of Alexander VI. The Pope is first seen in his ceremonial robes; but a leaf being raised, another figure is joined to the lower part of the former, and there appears the papal devil, the cross in his hand being changed to a pitchfork (Fig. 11). Attached to it is an explanation in German giving the legend of the Pope’s death. He was poisoned (1503) by the cup he had prepared for another man. It was afterwards said that he had secured the papacy by aid of the Devil. Having asked how long he would reign, the Devil returned an equivocal answer; and though Alexander understood that it was to be fifteen years, it proved to be only eleven. When in 1520 Pope Leo X. issued his formal bull against Luther, the reformer termed it ‘the execrable bull of Antichrist.’ An Italian poem of the time having represented Luther as the offspring of Megæra, the Germans returned the invective in a form more likely to impress the popular mind; namely, in a caricature (Fig. 12), representing the said Fury as nursing the Pope. This caricature is also of date 1545, and with it were others showing Alecto and Tisiphone acting in other capacities for the papal babe.

Fig. 12.—The Pope Nursed by Megæra.

The Lutherans had made the discovery that the number of the Apocalyptic Beast, 666, put into Hebrew numeral letters, contained the words Aberin Kadescha Papa (our holy father the Pope). The downfall of this Antichrist was a favourite theme of pulpit eloquence, and also with artists. A very spirited pamphlet was printed (1521), and illustrated with designs by Luther’s friend Lucas Cranach. It was entitled Passional Christi und Antichristi. The fall of the papal Antichrist (Fig. 13), has for its companion one of Christ washing the feet of his disciples.

But the Catholics could also make discoveries; and among many other things they found that the word ‘Luther’ in Hebrew numerals also made the number of the Beast. It was remembered that one of the earliest predictions concerning Antichrist was that he would travesty the birth of Christ from a virgin by being born of a nun by a Bishop. Luther’s marriage with the nun Catharine von Bora came sufficiently near the prediction to be welcomed by his enemies. The source of his inspiration as understood by Catholics is cleverly indicated in a caricature of the period (Fig. 14).

Fig. 13.—Antichrist’s Descent (L. Cranach).

The theory that the Papacy represents Antichrist has so long been the solemn belief of rebels against its authority, that it has become a vulgarised article of Protestant faith. On the other hand, Catholics appear to take a political and prospective view of Antichrist. Cardinal Manning, in his pastoral following the election of Leo XIII., said: ‘A tide of revolution has swept over all countries. Every people in Europe is inwardly divided against itself, and the old society of Christendom, with its laws, its sanctities, and its stability, is giving way before the popular will, which has no law, or rather which claims to be a law to itself. This is at least the forerunning sign of the Lawless One, who in his own time shall be revealed.’

Fig. 14.—Luther’s Devil as seen by Catholics.

Throughout the endless exchange of epithets, it has been made clear that Antichrist is the reductio ad absurdum of the notion of a personal Devil. From the day when the word was first coined, it has assumed every variety of shape, has fitted with equal precision the most contrarious things and persons; and the need of such a novel form at one point or another in the progress of controversy is a satire on the inadequacy of Satan and his ancient ministers. Bygone Devils cannot represent new animosities. The ascent of every ecclesiastical or theological system is traceable in massacres and martyrdoms; each of these, whether on one side or the other, helps to develop a new devil. The story of Antichrist shows devils in the making. Meantime, to eyes that see how every system so built up must sacrifice a virtue at every stage of its ascent, it will be sufficiently clear that every powerful Church is Adversary of the religion it claims to represent. Buddhism is Antibuddha; Islam is Antimohammed; Christianity is Antichrist.

1 Luke xxii. 31.

2 Amos ix. 8, 9.

3 1 Cor. v. 5.

4 2 Cor. xi. 13.

5 1 John iv. 2, 3.

6 Polycarp, Ep. to Philippians, vii.

7 2 Thess. ii.

8 2 Peter ii. 15.

9 John xvii. 12.

10 ‘But,’ says Professor King (Gnostics, p. 52), ‘a dispassionate examiner will discover that these two zealous Fathers somewhat beg the question in assuming that the Mithraic rites were invented as counterfeits of the Christian Sacraments; the former having really been in existence long before the promulgation of Christianity.’ Whatever may have been the incidents in the life of Christ connected with such things, it is certainly true, as Professor King says, that these ‘were afterwards invested with the mystic and supernatural virtues, in a later age insisted upon as articles of faith, by succeeding and unscrupulous missionaries, eager to outbid the attractions of more ancient ceremonies of a cognate character.’ In the porch of the Church Bocca della Verita at Rome, there is, or was, a fresco of Ceres shelling corn and Bacchus pressing grapes, from them falling the elements of the Eucharist to a table below. This was described to me by a friend, but when I went to see it in 1872, it had just been whitewashed over! I called the attention of Signor Rosa to this shameful proceeding, and he had then some hope that this very interesting relic might be recovered.

11 Op. iv. 511. Col. Agrip. 1616.

12 For full details of all these superstitions see Eisenmenger (Entd. Jud. li. Armillus); D’Herbelot (Bib. Orient. Daggiel); Buxtorf (Lexicon, Armillus); Calmet, Antichrist; and on the same word, Smith; also a valuable article in M’Clintock and Strong’s Cyc. Bib. Lit. (American).

13 Deutsch, ‘Lit. Remains.’ Islam.

Chapter XXII.

The Pride of Life.

The curse of Iblis—Samaël as Democrat—His vindication by Christ and Paul—Asmodäus—History of the name—Aschmedai of the Jews—Book of Tobit—Doré’s ‘Triumph of Christianity’—Aucassin and Nicolette—Asmodeus in the convent—The Asmodeus of Le Sage—Mephistopheles—Blake’s ‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell’—The Devil and the artists—Sádi’s Vision of Satan—Arts of the Devil—Suspicion of beauty—Earthly and heavenly mansions—Deacon versus Devil.

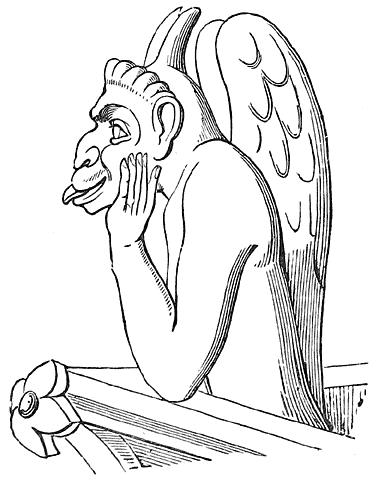

On the parapet of the external gallery of Nôtre Dame in Paris is the carved form, of human size, represented in our figure (15). There is in the face a remarkable expression of pride and satisfaction as he looks forth on the gay city and contemplates all the wickedness in it, but this satisfaction is curiously blended with a look of envy and lust. His elegant head-dress gives him the pomp becoming the Asmodeus presiding over the most brilliant capital in the world.

Fig. 15.—The Pride of Life.

His seat on the fine parapet is in contrast with the place assigned him in Eastern traditions—ruins and desert places,—but otherwise he fairly fulfilled, no doubt, early ideas in selecting his headquarters at Paris. A mussulman legend says that when, after the Fall of Man, Allah was mitigating the sentences he had pronounced, Iblis (who, as the Koran relates, pleaded and obtained the deferment of his consignment to Hell until the resurrection, and unlimited power over sinners who do not accept the word of Allah) asked—

‘Where shall I dwell in the meantime?

‘In ruins, tombs, and all other unclean places shunned by man.

‘What shall be my food?

‘All things slain in the name of idols.

‘How shall I quench my thirst?

‘With wine and intoxicating liquors.

‘What shall occupy my leisure hours?

‘Music, song, love-poetry, and dancing.

‘What is my watchword?

‘The curse of Allah until the day of judgment.

‘But how shall I contend with man, to whom thou hast granted two guardian angels, and who has received thy revelation?

‘Thy progeny shall be more numerous than his,—for for every man that is born, there shall come into the world seven evil spirits—but they shall be powerless against the faithful.’

Iblis with wine, song, and dance—the ‘pride of life’—is also said to have been aided in entering Paradise by the peacock, which he flattered.1

This fable, though later than the era of Mohammed in form, is as ancient as the myth of Eden in substance. The germ of it is already in the belief that Jehovah separated from the rest of the earth a garden, and from the human world a family of his own, and from the week a day of his own. The reply of the elect to the proud Gentile aristocracy was an ascetic caste established by covenant with the King of kings. This attitude of the pious caste turned the barbaric aristocrats, in a sense, to democrats. Indeed Samaël, in whom the execrated Dukes of Edom were ideally represented, might be almost described as the Democratic Devil. According to an early Jewish legend, Jehovah, having resolved to separate ‘men’ (i.e., Jews) from ‘swine’ (i.e., idolaters, Gentiles), made circumcision the seal on them as children of Abraham. There having been, however, Jews who were necessarily never circumcised, their souls, it was arranged, should pass at death into the forms of certain sacred birds where they would be purified, and finally united to the elect in Paradise. Now, Samaël, or Adam Belial as he was sometimes called, is said to have appealed to the Creator that this arrangement should include all races of beings. ‘Lord of the world!’ he said, ‘we also are of your creation. Thou art our father. As thou savest the souls of Israel by transforming them that they may be brought back again and made immortal, so also do unto us! Why shouldst thou regard the seed of Abraham before us?’ Jehovah answered, ‘Have you done the same that Abraham did, who recognised me from his childhood and went into Chaldean fire for love of me? You have seen that I rescued him from your hands, and from the fiery oven which had no power over him, and yet you have not loved and worshipped me. Henceforth speak no more of good or evil.’2

The old rabbinical books which record this conversation do not report Samaël’s answer; nor is it necessary: that answer was given by Jesus and Paul breaking down the partitions between Jew and Gentile. It was quite another thing, however, to include the world morally. Jesus, it would seem, aimed at this also; he came ‘eating and drinking,’ and the orthodox said Samaël was in him. Personally, he declined to substitute even the cosmopolitan rite of baptism for the discredited national rite of circumcision. But Paul was of another mind. His pharisaism was spiritualised and intensified in his new faith, to which the great world was all an Adversary.

It was a tremendous concession, this giving up of the gay and beautiful world, with its mirth and amusements, its fine arts and romance—to the Devil. Unswerving Nemesis has followed that wild theorem in many forms, of which the most significant is Asmodeus.

Asmodäus, or Aêshma-daêva of the Zend texts, the modern Persian Khasm, is etymologically what Carlyle might call ‘the god Wish;’ aêsha meaning ‘wish,’ from the Sanskrit root ish, ‘to desire.’ An almost standing epithet of Aêshma is Khrvîdra, meaning apparently ‘having a hurtful weapon or lance.’ He is occasionally mentioned immediately after Anrô-mainyus (Ahriman); sometimes is expressly named as one of his most prominent supporters. In the remarkable combat between Ahuro-mazda (Ormuzd) and Anrô-mainyus, described in Zam. Y. 46, the good deity summons to his aid Vohumano, Ashavahista, and Fire; while the Evil One is aided by Akômano, Aêshma, and Aji-Daháka.3 Here, therefore, Aêshma appears as opposed to Ashavahista, ‘supreme purity’ of the Lord of Fire. Aêshma is the spirit of the lower or impure Fire, Lust and Wrath. A Sanskrit text styles him Kossa-deva, ‘the god of Wrath.’ In Yaçna 27, 35, Śraosha, Aêshma’s opponent, is invoked to shield the faithful ‘in both worlds from Death the Violent, from Aêshma the Violent, from the hosts of Violence that raise aloft the terrible banner—from the assaults of Aêshma that he makes along with Vídátu (‘Divider, Destroyer’), the demon-created.’ He is thus the leading representative of dissolution, the fatal power of Ahriman. Ormuzd is said to have created Śraosha to be the destroyer of ‘Aêshma of the fatal lance.’ Śraosha (‘the Hearer’) is the moral vanquisher of Aêshma, in distinction from Haoma, who is his chief opponent in the physical domain.

Such, following Windischmann,4 is the origin of the devil whom the apocryphal book of Tobit has made familiar in Europe as Asmodeus. Aschmedai, as the Jews called him, appears in this story as precisely that spirit described in the Avesta—the devil of Violence and Lust, whose passion for Sara leads him to slay her seven husbands on their wedding-night. The devils of Lust are considered elsewhere, and Asmodeus among them; there is another aspect of him which here concerns us. He is a fastidious devil. He will not have the object of his passion liable to the embrace of any other. He cannot endure bad smells, and that raised by the smoke of the fish-entrails burnt by Tobit drives him ‘into the utmost parts of Egypt, where the angel bound him.’ It is, however, of more importance to read the story by the light of the general reputation of Aschmedai among the Jews and Arabians. It was notably that of the devil represented in the Moslem tradition at the beginning of this chapter. He is the Eastern Don Giovanni and Lothario; he plies Noah and Solomon with wine, and seduces their wives, and always aims high with his dashing intrigues. He would have cried Amen to Luther’s lines—

Who loves not wine, woman, and song,

He lives a fool his whole life long.

Besides being an aristocrat, he is a scholar, the most learned Master of Arts, educated in the great College of Hell, founded by Asa and Asael, as elsewhere related. He was fond of gaming; and so fashionable that Calmet believed his very name signifies fine dress.

Now, the moral reflections in the Book of Tobit, and its casual intimations concerning the position of the persons concerned, show that they were Jewish captives of the humblest working class, whose religion is of a type now found chiefly among the more ignorant sectarians. Tobit’s moral instructions to his son, ‘In pride is destruction and much trouble, and in lewdness is decay and much want,’ ‘Drink not wine to make thee drunken,’ and his careful instructions about finding wealth in the fear of God, are precisely such as would shape a devil in the image of Asmodeus. Tobit’s moral truisms are made falsities by his puritanism: ‘Prayer is good with fasting and alms and righteousness;’ ‘but give nothing to the wicked;’ ‘If thou serve God he will repay thee.’

‘Cakes and ale’ do not cease to exist because Tobits are virtuous; but unfortunately they may be raised from their subordinate to an insubordinate place by the transfer of religious restraints to the hands of Ignorance and Cant. Asmodeus, defined against Persian and Jewish asceticism and hypocrisy, had his attractions for men of the world. Through him the devil became perilously associated with wit, gallantry, and the one creed of youth which is not at all consumptive—

Grey is all Theory,

Green Life’s golden-fruited tree!

Especially did Asmodeus represent the subordination of so-called ‘religious’ and tribal distinctions to secular considerations. As Samaël had petitioned for an extension of the Abrahamic Covenant to all the world and failed to secure it from Jehovah, Asmodeus proposed to disregard the distinction. There is much in the Book of Tobit which looks as if it were written especially with the intention of persuading Jewish youth, tempted by Babylonians to marriage, that their lovers might prove to be succubi or incubi. Tobit implores his son to marry in his own tribe, and not take a ‘strange woman.’ Asmodeus was as cosmopolitan as the god of Love himself, and many of his uglier early characteristics were hidden out of sight by such later developments.

Gustave Doré has painted in his vivid way the ‘Triumph of Christianity.’ In it we see the angelic hosts with drawn swords overthrowing the forms adored of paganism—hurling them headlong into an abyss. So far as the battle and victory go, this is just the conception which an early christian would have had of what took place through the advent of Christ. It filled their souls with joy to behold by Faith’s vision those draped angels casting down undraped goddesses; they would delight to imagine how the fall might break the bones of those beautiful limbs. For they never thought of these gods and goddesses as statues, but as real seductive devils; and when these christians had brought over the arts, they often pictured the black souls coming out of these fair idols as they fell.

Doré may have tried to make the angels as beautiful as the goddesses, but he has not succeeded. In this he has interpreted the heart behind every deformity which was ever added to a pagan deity. The horror of the monks was transparent homage. Why did they starve and scourge their bodies, and roll them in thorns? Because not even by defacing the beautiful images were they able to expel from their inward worship the lovely ideals they represented.

It is not difficult now to perceive that the old monks were consigning the pagan ideals to imaginary and themselves to actual hells, in full hope of thereby gaining permanent possession of the same beauty abjured on earth. The loveliness of the world was transient. They grew morbid about death; beneath the rosiest form they saw the skeleton. The heavenly angels they longed for were Venuses and Apollos, with no skeletons visible beneath their immortalised flesh. They never made sacrifices for a disembodied heaven. The force of self-crucifixion lay in the creed—‘I believe in the resurrection of the body, and the life everlasting.’

The world could not generally be turned into a black procession at its own funeral. In proportion to the conquests of Christianity must be its progressive surrender to the unconquerable—to human nature. Aphrodite and Eros, over whose deep graves nunneries and monasteries had been built, were the first to revive, and the story, as Mr. Pater has told it, is like some romantic version of Ishtar’s Descent into Hades and her resurrection.5 While as yet the earth seemed frostbound, long before the Renaissance, the song of the turtle was heard in the ballad of Aucassin and Nicolette. The christian knight will marry the beautiful Saracen, and to all priestly warnings that he will surely go to hell, replies, ‘What could I do in Paradise? I care only to go where I can be with Nicolette. Who go to Paradise? Old priests, holy cripples, dried-up monks, who pass their lives before altars. I much prefer Hell, where go the brave, the gay, and beautiful. There will be the players on harps, the classic poets and singers; and there I shall not be parted from Nicolette!’

Along with pretty Saracen maidens, or memories of them, were brought back into Europe legends of Asmodeus. Aphrodite and Eros might disguise themselves in his less known and less anathematised name, so that he could manage to sing of his love for Sara, of Parsi for Jewess, under the names of christian Aucassin and saracen Nicolette. In the Eastern Church he reappeared also. There are beautiful old pictures which show the smart cavalier, feather-in-cap, on the youth’s left, while on his right stands ‘grey Theory’ in the form of a long-bearded friar. Such pictures, no doubt, taught for many a different lesson from that intended—namely, that the beat of the heart is on the left.

Where St. Benedict rolled himself in thorns for dreaming of his (deserted) ‘Nicolette,’ St. Francis planted roses; and the Latin Church had to recognise this evolution of seven centuries. They hid the thorns in the courts of convents, and sold the roses to the outside world as indulgences. But as Asmodeus had not respected the line between Jew and Gentile in Nineveh, so he passed over that between priest, nun, and worldling in the West. In the days of Witchcraft the Church was scandalised by the rumour that the nuns of the Franciscan Convent of Louviers had largely taken to sorcery, and were attending the terrible ‘Witches’ Sabbaths.’ The nun most prominent in this affair was one Madeleine Bavent. The priests announced that she had confessed that she was borne away to the orgies by the demon Asmodeus, and that he had induced her to profane the sacred host. It turned out that the nuns had engaged in intrigues with the priests who had charge of them—especially with Fathers David, Picard, and Boulé—but Asmodeus was credited with the crime, and the nuns were punished for it. Madeleine was condemned to life-long penance, and Picard anticipated the fire by a suicide, in which he was said to have been assisted by the devil.

Following the rabbinical tradition which represented him as continually passing from the high infernal College of Asa and Asael to the earth to apply his arts of sorcery, Asmodeus gained a respectable position in European literature through the romance of Le Sage (‘Le Diable Boiteux’), and his fame so gained did much to bring about in France that friendly feeling for the Devil which has long been a characteristic of French literature. A very large number of books, periodicals, and journals in France have gained popularity through the Devil’s name. Asmodeus was, in fact, the Arch-bohemian. As such, he largely influenced the conception of Mephistopheles as rendered by Goethe—himself the Prince of Bohemians. The old horror of Asmodeus for bad smells is insulted in the name Mephistopheles, and this devil is many rolled into one; yet in many respects his kinship to Asmodeus is revealed. All the dried starveling Anthonys and Benedicts are, in a cultured way, present in the theologian and scholar Faust; all the sweet ladies that haunted their seclusion became realistic in Gretchen. She is the Nemesis of suppressed passions.

One province of nature after another has been recovered from Asceticism. In this case Ishtar has had to regain her apparel and ornaments at successive portals that are centuries, and they are not all recovered yet. But we have gone far enough, even in puritanised England, to produce a ‘madman’ far-seeing enough to behold The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. The case of Asmodeus is stated well, albeit radically, by William Blake, in that proverb which was told him by the devils, whom he alone of midnight travellers was shrewd enough to consult: ‘The pride of the peacock is the glory of God; the lust of the goat is the bounty of God; the wrath of the lion is the wisdom of God.’ When that statement is improved, as it well may be, it will be when those who represent religion shall have learned that human like other nature is commanded by obedience.

In this connection may be mentioned a class of legends indicating the Devil’s sensitiveness with regard to his personal appearance. The anxiety of the priests and hermits to have him represented as hideous was said to have been warmly resented by Satan, one of the most striking being the legend of many versions concerning a Sacristan, who was also an artist, who ornamented an abbey with a devil so ugly that none could behold it without terror. It was believed he had by inspiration secured an exact portrait of the archfiend. The Devil appeared to the Sacristan, reproached him with having made him so ugly, and threatened to punish him grievously if he did not make him better looking. Although this menace was thrice repeated, the Sacristan refused to comply. The Devil then tempted him into an intrigue with a lady of the neighbourhood, and they eloped after robbing the abbey of its treasure. But they were caught, and the Sacristan imprisoned. The Devil then appears and offers to get him out of his trouble if he will only destroy the ugly likeness, and make another and handsomer. The Sacristan consented, and suddenly found himself in bed as if nothing had happened, while the Devil in his image lay in chains. The Devil when discovered vanished; the Sacristan got off on the theory that crimes and all had been satanic juggles. But the Sacristan took care to substitute a handsome devil for the ugly one. In another version the Sacristan remained faithful to his original portraiture of the Devil despite all menaces of the latter, who resolved to take a dire revenge. While the artist was completing his ornamentation of the abbey with an image of the Virgin, made as beautiful as the fiend near it was ugly, the Devil broke the ladder on which he was working, and a fatal fall was only prevented by the hand of the Madonna he had just made, which was outstretched to sustain him. The accompanying picture of this scene (Fig. 16) is from ‘Queen Mary’s Psalter’ in the British Museum.

Vasari relates that when Spinello of Arezzo, in his famous fresco of the fall of the rebellious angels, had painted the hideous devil with seven faces about his body, the fiend appeared to him in the same form, and asked the artist where he had seen him in so frightful an aspect, and why he had treated him so ignominiously. When Spinello awoke in horror, he fell into a state of gloom, and soon after died.

Fig. 16.—The Artist’s Rescue.

The Persian poet Sádi has a remarkable passage conceived in the spirit of these legends, but more kindly.

I saw the demon in a dream,

But how unlike he seemed to be

To all of horrible we dream,

And all of fearful that we see.

His shape was like a cypress bough,

His eyes like those that Houris wear,

His face as beautiful as though

The rays of Paradise were there.

I near him came, and spoke—‘Art thou,’

I said, ‘indeed the Evil One?

No angel has so bright a brow,

Such yet no eye has looked upon.

Why should mankind make thee a jest,

When thou canst show a face like this?

Fair as the moon in splendour drest,

An eye of joy, a smile of bliss!

The painter draws thee vile to sight,

Our baths thy frightful form display;

They told me thou wert black as night,

Behold, thou art as fair as day!’

The lovely vision’s ire awoke,

His voice was loud and proud his mien:

‘Believe not, friend!’ ’twas thus he spoke,

‘That thou my likeness yet hast seen:

The pencil that my portrait made

Was guided by an envious foe;

In Paradise I man betrayed,

And he, from hatred, paints me so.’

Boehme relates that when Satan was asked the cause of God’s enmity to him and his consequent downfall, he replied, ‘I wished to be an artist.’ There is in this quaint sentence a very true intimation of the allurements which, in ancient times, the arts of the Gentile possessed for the Jews and christian judaisers. Indeed, a similar feeling towards the sensuous attractions of the Catholic and Ritualistic Churches is not uncommon among the prosaic and puritanical sects whose younger members are often thus charmed away from them. Dr. Donne preached a sermon before Oliver Cromwell at Whitehall, in which he affirmed that the Muses were damned spirits of devils; and the discussion on the Drama which occurred at Sheffield Church Congress (1878), following Dr. Bickerstith’s opening discourse on ‘the Devil and his wiles,’ shows that the Low Church wing cherishes much the same opinion as that of Dr. Donne. The dread of the theatre among some sects amounts to terror. The writer remembers the horror that spread through a large Wesleyan circle, with which he was connected, when a distinguished minister of that body, just returned from Europe, casually remarked that ‘the theatre at Rome seemed to be poorly supported.’ The fearful confession spread through the denomination, and it was understood that the observant traveller had ‘made shipwreck of faith.’ The Methodist instinct told true: the preacher became an accomplished Gentile.

Music made its way but slowly in the Church, and the suspicion of it still lingers among many sects. The Quakers took up the burthen of Epiphanius who wrote against the flute-players, ‘After the pattern of the serpent’s form has the flute been invented for the deceiving of mankind. Observe the figure that the player makes in blowing his flute. Does he not bend himself up and down to the right hand and to the left, like unto the serpent? These forms hath the Devil used to manifest his blasphemy against things heavenly, to destroy things upon earth, to encompass the world, capturing right and left such as lend an ear to his seductions.’ The unregenerate birds that carol all day, be it Sabbath or Fast, have taught the composer that his best inspiration is from the Prince of the Air. Tartini wrote over a hundred sonatas and as many concertos, but he rightly valued above them all his ‘Sonata del Diavolo.’ Concerning this he wrote to the astronomer Lalande:—‘One night, in the year 1713, I dreamed that I had made a compact with his Satanic Majesty, by which he was received into my service. Everything succeeded to the utmost of my desires, and my every wish was anticipated by my new domestic. I thought that, in taking up my violin to practise, I jocosely asked him if he could play on this instrument. He answered that he believed he was able to pick out a tune; when, to my astonishment, he began a sonata, so strange, and yet so beautiful, and executed in so masterly a manner, that in the whole course of my life I had never heard anything so exquisite. So great was my amazement that I could scarcely breathe. Awakened by the violence of my feelings, I instantly seized my violin, in the hope of being able to catch some part of the ravishing melody which I had just heard, but all in vain. The piece which I composed according to my scattered recollections is, it is true, the best I ever produced. I have entitled it, ‘Sonata del Diavolo;’ but it is so far inferior to that which had made so forcible an impression on me, that I should have dashed my violin into a thousand pieces, and given up music for ever in despair, had it been possible to deprive myself of the enjoyments which I receive from it.’

The fire and originality of Tartini’s great work is a fine example of that power which Timoleon called Automatia, and Goethe the Dämonische,—‘that which cannot be explained by reason or understanding; it is not in my nature, but I am subject to it.’ ‘It seems to play at will with all the elements of our being.’

The Puritans brought upon England and America that relapse into the ancient asceticism which was shown in the burning of great pictures by Cromwell’s Parliament. It is shown still in the jealousy with which the puritanised mind in both countries views all that aims at the simple decoration of life, and whose ministry is to the sense of beauty. On that day of the week when England and New England hebraise, as Matthew Arnold says, it is observable that the sabbatarian fury is especially directed against everything which proposes to give simple pleasure or satisfy the popular craving for beauty. Sabbatarianism sees a great deal of hard work going on, but is not much troubled so long as it is ugly and dismal work. It utters no cry at the thousands of hands employed on Sunday railways, but is beside itself if one of the trains takes excursionists to the seaside, and is frantic at the thought of a comparatively few persons being employed on that day in Museums and Art Galleries. It is a survival of the old feeling that the Devil lurks about all beauty and pleasure.

A money-making age has measurably dispersed the superstitions which once connected the Devil with all great fortunes. For a long time, and in many regions of the world, the Jews suffered grievously by being supposed to get their wealth by the Devil’s help. Their wealth (largely the result of their not exchanging it for worldly enjoyments) so often proved their misfortune, that it was easy to illustrate by their case the monkish theory that devil’s gifts turn to ashes. Princes were indefatigable in relieving the Jews of such ashes, however. The Lords of Triar, who possessed the mines of Glucksbrunn, were believed to have been guided to them by a gold stag which often appeared to them—of course the Devil. It is related that when St. Wolfram went to convert the Frislanders, their king, Radbot, was prevented from submitting to baptism by a diabolical deception. The Devil appeared to him as an angel clothed in a garment woven of gold, on his head a jewelled diadem, and said, ‘Bravest of men! what has led thee to depart from the Prince of thy gods? Do it not; be steadfast to thy religion and thou shalt dwell in a house of gold which I will give into thy possession to all eternity. Go to Wolfram to-morrow, ask him about those bright dwellings he promises thee. If he cannot show them, let both parties choose an ambassador; I will be their leader and will show them the gold house I promise thee.’ St. Wolfram being unable to show Radbot the bright dwellings of Paradise, one of his deacons was sent along with a representative of the king, and the Devil (disguised as a traveller) took them to the house of gold, which was of incredible size and splendour. The Deacon exclaimed, ‘If this house be made by God it will stand for ever; if by the Devil, it must vanish speedily.’ Whereupon he crossed himself; the house vanished, and the Deacon found himself with the Frislander in a swamp. It took them three days to extricate themselves and return to King Radbot, whom they found dead.

The ascetic principle which branded the arts, interests, pursuits, and pleasures of the world as belonging to the domain of Satan, involved the fatal extreme of including among the outlawed realms all secular learning. The scholar and man of science were also declared to be inspired by the ‘pride of life.’ But this part of our subject requires a separate chapter.