Eighteenth lace stitch (fig. 737).—This is the first of a series of lace stitches, often met with in old Venetian lace, and which can therefore with perfect right be called, Venetian stitches.

Owing to the manner and order in which the rows of stitches are connected and placed above one another, they form less transparent grounds than those we have hitherto described.

In these grounds you begin by making the row of loops, then you throw a thread across on the same level and in coming back, pass the needle through the row of loops under the thread stretched across, and under the stitch of the previous row.

Nineteenth lace stitch (fig. 738).—The close stitch here represented is more common in Venetian lace than the loose stitch given in fig. 737.

Twentieth lace stitch (fig. 739).—By missing some loops of the close ground in one row and replacing them by the same number in the next, small gaps are formed, and by a regular and systematic missing and taking up of stitches, in this way, extremely pretty grounds can be produced.

Twenty-first lace stitch (fig. 740).—These close lace stitches, can be varied in all sorts of other ways by embroidering the needle-made grounds.

In fig. 740, you have little tufts in darning stitch, and in a less twisted material than the close stitches of the ground, worked upon the ground.

If you use Fil à dentelle D.M.C (lace thread) for the ground, you should take either Coton à repriser D.M.C (darning cotton), or better still, Coton surfin D.M.C[A] for the tufts. The ground can also be ornamented with little rings of button-holing, stars or flowerets in bullion or some other fancy stitch.

Twenty-second lace stitch (fig. 741).—For the above three stitches and the three that follow, the work has to be held, so that the finished rows are turned to the worker and the needle points to the outside of the hand. In the first row, from left to right, take hold of the thread near the end that is in the braid, lay it from left to right under the point of the needle, and bring it back again to the right, over the same. Whilst twisting the thread in this way round the needle with the right hand, you must hold the eye of the needle under the left thumb.

When you have laid the thread round draw the needle through the loops; the bars must stand straight and be of uniform length. Were they to slant or be at all uneven, we should consider the work badly done.

In the row that is worked from left to right, the thread must be twisted round the needle, likewise from left to right.

Twenty-third lace stitch (fig. 742).—This is begun with the same stitches as fig. 741, worked from right to left. You then take up every loop that comes between the vertical bars with an overcasting stitch, drawing the thread quite out, and tightening it as much as is necessary after each stitch. You cannot take several stitches on the needle at the same time and draw out the thread for them all at once, as this pulls the bars out of their place.

Twenty-fourth lace stitch (fig. 743).—This is often called the Sorrento stitch.

Every group of three bars of stitches is separated from the next by a long loop, round which the thread is twisted in its backward course. In each of the succeeding rows you place the first bar between the first and second of the preceding row, and the third one in the long loop, so that the pattern advances, as it were in steps.

Twenty-fifth and twenty-sixth lace stitches (figs. 744 and 745).—These two figures show how the relative position of the groups of bars may be varied.

Both consist of the same stitches as those described in fig. 741. The thread that connects the groups should be tightly stretched, so that the rows may form straight horizontal lines.

Twenty-seventh lace stitch (fig. 746).—Begin by making two rows of net stitches, fig. 720, then two of close ones, fig. 738, and one row like those of fig. 741.

If you want to lengthen the bars, twist the thread once or twice more round the needle. You can also make one row of bars surmounted by wheels, as shown in fig. 765, then one more row of bars and continue with close stitches.

Twenty-eighth lace stitch (fig. 747).—Between every group of three bars, set close together, leave a space of a corresponding width; then bring the thread back over the bars, as in figs. 737, 738 and 739, without going through the loops. In the second row, you make three bars in the empty space, two over the three bars of the first row and again three in the next empty space. The third row is like the first.

Twenty-ninth lace stitch (fig. 748).—This stitch, known as Greek net stitch, can be used instead of button-hole bars for filling in large surfaces.

Make bars from left to right, a little distance apart as in fig. 741, leaving the loops between rather slack, so that when they have been twice overcast by the returning thread, they may still be slightly rounded. In the next row, you make the bar in the middle of the loop and lift it up sufficiently with the needle, for the threads to form a hexagon like a net mesh.

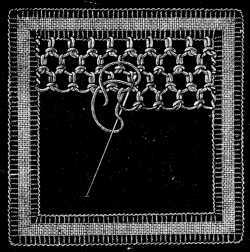

Thirtieth lace stitch (fig. 749). After a row of pairs of button-hole stitches set closely together, with long loops between, as long as the space between the pairs, throw the thread across in a line with the extremities of the loops, fasten it to the edge of the braid and make pairs of button-hole stitches, as in the first row above it.

The loops must be perfectly regular, to facilitate which, guide lines may be traced across the pattern, and pins stuck in as shown in the figure, round which to carry the thread.

Thirty-first lace stitch (fig. 750).—At first sight this stitch looks very much like the preceding one, but it differs entirely from it in the way in which the threads are knotted. You pass the needle under the loop and the laid thread, then stick in the pin at the right distance for making the long loop, bring the thread round behind the pin, make a loop round the point of the needle, as shows in the engraving, and pull up the knot.

Thirty-second lace stitch (fig. 751).—To introduce a greater variety into lace stitches, netting can also be imitated with the needle. You begin with a loop in the corner of a square and work in diagonal lines. The loops are secured by means of the same stitch shown in fig. 750, and the regularity of the loops ensured, as it is there, by making them round a pin, stuck in at the proper distance. The squares or meshes must be made with the greatest accuracy; that being the case, most of the stitches described in the preceding chapter can be worked upon them, and the smallest spaces can be filled with delicate embroidery.

Thirty-third lace stitch (fig. 752).—This stitch is frequently met with in the oldest Irish lace, especially in the kind where the braids are joined together by fillings not bars. At first sight, it looks merely like a close net stitch, the ground and filling all alike, so uniform is it in appearance, but on a closer observation it will be found to be quite a different stitch from any of those we have been describing.

The first stitch is made like a plain net stitch, the second consists of a knot that ties up the loop of the first stitch. Fillings of this kind must be worked as compactly as possible, so that hardly any spaces are visible between the individual rows.

Thirty-fourth lace stitch (fig. 753).—To fill in a surface with this stitch, known as the wheel or spider stitch, begin by laying double diagonal threads to and fro, at regular distances apart, so that they lie side by side and are not twisted. When the whole surface is covered with these double threads, throw a second similar series across them, the opposite way. The return thread, in making this second layer, must be conducted under the double threads of the first layer and over the single thread just laid, and wound two or three times round them, thereby forming little wheels or spiders, like those already described in the preceding chapter in figs. 653 and 654.

Thirty-fifth lace stitch (fig. 754).—Begin by making a very regular netted foundation, but without knots, where the two layers of threads intersect each other.

Then, make a third layer of diagonal threads across the two first layers, so that all meet at the same points of intersection, thus forming six rays divergent from one centre. With the fourth and last thread, which forms the seventh and eighth ray, you make the wheel over seven threads, then slip the needle under it and carry it on to the point for the next wheel.

Thirty-sixth lace stitch (fig. 755).—After covering all the surface to be embroidered, with threads stretched in horizontal lines, you cover them with loops going from one to the other and joining themselves in the subsequent row to the preceding loops.

The needle will thus have to pass underneath two threads. Then cover this needle-made canvas with cones worked in close darning stitches, as in figs. 648, 716 and 717.

Thirty-seventh lace stitch (fig. 756).—Here, by means of the first threads that you lay, you make an imitation of the Penelope canvas used for tapestry work, covering the surface with double threads, a very little distance apart, stretched both ways. The second layer of threads must pass alternately under and over the first, where they cross each other, and the small squares thus left between, must be encircled several times with thread and then button-holed; the thicker the foundation and the more raised and compact the button-holing upon it is, the better the effect will be. Each of these little button-holed rings should be begun and finished off independently of the others.

Thirty-eighth lace stitch (fig. 757).—Plain net stitch being quicker to do than any other, one is tempted to use it more frequently; but as it is a little monotonous some openwork ornament upon it is a great improvement; such for instance as small button-holed rings, worked all over the ground at regular intervals. Here again, as in the preceding figure the rings must be made independently of each other.

Thirty-ninth lace stitch (fig. 758).—Corded bars, branching out into other bars, worked in overcasting stitches, may also serve as a lace ground.

You lay five or six threads, according to the course the bars are to take; you overcast the branches up to the point of their junction with the principal line, thence you throw across the foundation threads for another branch, so that having reached a given point and coming back to finish the threads left uncovered in going, you will often have from six to eight short lengths of thread to overcast.

Overcasting stitches are always worked from right to left.

Fortieth lace stitch (fig. 759).—Of all the different kinds of stitches here given, this, which terminates the series, is perhaps the one requiring the most patience. It was copied from a piece of very old and valuable Brabant lace, of which it formed the entire ground. Our figure of course represents it on a very magnified scale, the original being worked in the finest imaginable material, over a single foundation thread.

In the first row, after the three usual foundation threads are laid, you make the button-hole stitches to the number of eight or ten, up to the point from which the next branch issues, from the edge of the braid, that is, upwards.

Then you bring the needle down again and button-hole the second part of the bar, working from right to left.

A picot, like the one described in fig. 701, marks the point where the bars join. More picots of the same kind may be added at discretion.

Wheel composed of button-hole bars (figs. 760, 761, 762, 763).—As we have already more than once given directions for making wheels, not only in the present chapter, but also in the one on netting, there is no need to enlarge on the kind of stitches to be used here, but we will explain the course of the thread in making wheels, composed of button-hole bars in a square opening.

Fig. 760. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

Making and taking up the loops.

Fig. 760. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

Making and taking up the loops.

Fig. 761. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

The button-holing begun.

Fig. 761. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

The button-holing begun.

Fig. 760 shows how the first eight loops which form the foundation of the bars are made.

In fig. 761 you will see that a thread has been passed through the loops, for the purpose of drawing them in and making a ring in addition to which, two threads added to the loop serve as padding for the button-hole stitches; the latter should always be begun on the braid side. Fig. 762 represents the bar begun in fig. 761 completed, and the passage of the thread to the next bar, and fig. 763 the ring button-holed after the completion of all the bars.

Fig. 762. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

Passing from one bar to the other.

Fig. 762. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

Passing from one bar to the other.

Fig. 763. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

Bars and ring finished.

Fig. 763. Wheel composed of button-hole bars.

Bars and ring finished.

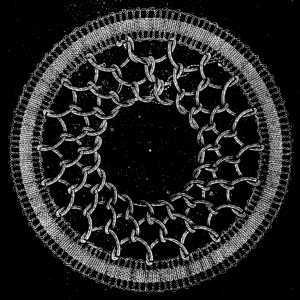

Filling in round spaces (figs. 764, 765, 766).—The stitches best adapted for filling in round spaces are those that can be drawn in and tightened to the required circumference, or those that admit of the number being reduced, regularly, in each round.

In tacking braids on to circular patterns, the inside edges, as we pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, have to be drawn in with overcasting stitches in very fine thread.

Fig. 764 shows how to fill in a round space with net stitches. It will be observed that the loop which begins the row, has the thread of the loop with which it terminates, wound round it, which thread then passes on to the second series of stitches. In the same manner you pass to the third row after which you pick up all the loops and fasten off the thread by working back to the braid edge over all the rows of loops, following the course indicated by the dotted line.

Fig. 765. Filling in round spaces.

First circle of wheels begun.

Fig. 765. Filling in round spaces.

First circle of wheels begun.

Fig. 766. Filling in round spaces.

The two circles of wheels finished.

Fig. 766. Filling in round spaces.

The two circles of wheels finished.

Fig. 765 shows how to finish a row of loops with wheels worked upon three threads only. In the first row, you make a wheel over each bar; in the second, you make a bar between every two wheels; in the third, the wheels are only made over every second bar; a fourth row of bars which you pick up with a thread completes the interior of the circle, then you work along the bars with overcasting stitches, fig. 766, to carry the thread back to the edge of the braid where you fasten it off.

Needle-made picots (figs. 767, 768, 769).—The edges and outlines of Irish lace are generally bordered with picots, which as we have already said can be bought ready-made (see fig. 692). They are not however very strong and we cannot recommend them for lace that any one has taken the pains to make by hand.

In fig. 767, the way to make picots all joined together is described. You begin, as in fig. 762, by a knot, over which the thread is twisted as indicated in the engraving.

It is needless to repeat that the loops should all be knotted in a line, all be of the same length and all the same distance apart.

Fig. 768 represents the kind of needle-made picots which most resemble the machine-made ones, and fig. 769 show us the use of little scallops surmounted by picots, made in bullion stitch.

One or two rows of lace stitch fig. 736, or the first rows of figs. 749, 750, can also be used in the place of picots.

Irish lace (fig. 770).—English braids or those braids which are indicated at the foot of the engraving must be tacked down on to the pattern and gathered on the inside edge, wherever the lines are curved, as explained in fig. 693; in cases however where only Lacet superfin D.M.C[A] is used, the needle should be slipped in underneath the outside threads, so that the thread with which you draw in the braid be hidden.

The braids are joined together where they meet with a few overcasting stitches, as shown in the illustration.

Here, we find one of the lace stitches used instead of picots; the first row of fig. 736 always makes a nice border for Irish lace.

Irish lace (fig. 771).—This pattern, which is more complicated and takes more time and stitches than the preceding one, can also be executed with one or other of the braids mentioned at the beginning of the chapter; but it looks best made with a close braid.

Fig. 771. Irish lace.

Fig. 771. Irish lace.Materials: Lacet surfin D.M.C No. 5, white or écru and Fil d’Alsace D.M.C Nos. 40 to 150, or Fil à dentelle D.M.C Nos. 50 to 150.

The bars, which in the illustration are simply button-holed may also be ornamented with picots of one kind or another; the interior spaces of the figure on the left can be filled, instead of with corded bars, with one of the lace stitches we have described, either fig. 720, 721, or 732, any one of which is suitable for filling in small spaces like these.

In the figure on the right, the ring of braid may be replaced by close button-hole stitches, made over several foundation threads or over one thick thread, such as Fil à pointer D.M.C No. 10 or 20[A] to make them full and round.

You begin the ring on the inside and increase the number of stitches as the circumference increases.

Any of the stitches, from fig. 720 to fig. 743, can be introduced here.

Irish lace (fig. 772).—Here we find one of the fillings above alluded to, fig. 751, used as a ground for the flowers and leaves. For the design itself some of the closer stitches described in this chapter, should be selected. When the actual lace, is finished you sew upon the braid a thin cord, made of écru Cordonnet 6 fils D.M.C, as described in the chapter on different kinds of fancy work. Cords of this kind can be had ready made, but the hand-made ones are much to be preferred, being far softer and more supple than the machine-made.

Fig. 772. Irish lace.

Fig. 772. Irish lace.Materials: English braid with open edge.—For the lattice work: Fil d’Alsace D.M.C in balls Nos. 50 to 100 or Fil à dentelle D.M.C Nos. 50 to 100, white. For the cord: Cordonnet 6 fils D.M.C No. 15, écru.[A]

Irish lace (fig. 773).—This lace, more troublesome than the preceding ones to make, is also much more valuable and effective. The ground is composed entirely of bars, like the ones described in fig. 761, the branches, true to the character of the work are worked in the close stitch represented in fig. 755, and the flowers in double net stitch, fig. 721.

Fig. 773. Irish lace.

Fig. 773. Irish lace.Materials—For the cord: Cordonnet 6 fils D.M.C Nos. 15 to 25. For the bars and lace stitches: Fil à dentelle D.M.C No. 200.[A]

In working the above fillings, the thread must not, as in lace made with braid, be carried on from one point to the other by overcasting stitches along the braid edges, but should be drawn out horizontally through the cord and back again the same way, giving the needle in so doing a slightly slanting direction.

FOOTNOTES:

Venetian lace of the xvi century.

Venetian lace of the xvi century.