Dear Mrs. Worldly,

A young cousin of mine, David Blakely from Chicago, is staying with us.

May Pauline take him to your dance on Friday? If it will be inconvenient for you to include him, please do not hesitate to say so frankly.

Very sincerely yours,

Caroline Robinson Town.

Answer:

Dear Mrs. Town,

I shall be delighted to have Pauline bring Mr. Blakely on the tenth.

Sincerely yours,

Edith Worldly.

Or

A man might write for an invitation for a friend. But a very young girl should not ask for an invitation for a man—or anyone—since it is more fitting that her mother ask for her. An older girl might say to Mrs. Worldly, "My cousin is staying with us, may I bring him to your dance?" Or if she knows Mrs. Worldly very well she might send a message by telephone: "Miss Town would like to know whether she may bring her cousin, Mr. Michigan, to Mrs. Worldly's dance."

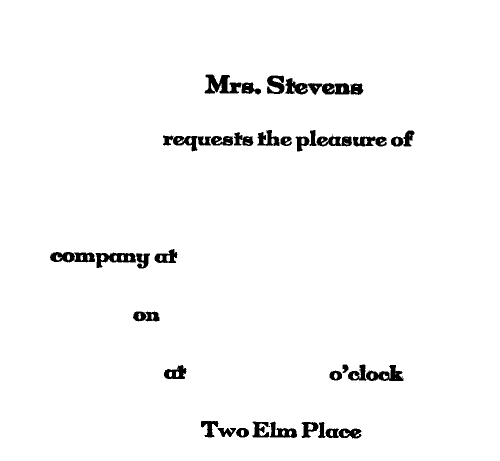

Invitations to important entertainments are nearly always especially engraved, so that nothing is written except the name of the person invited; but, for the hostess who entertains constantly, a card which is engraved in blank, so that it may serve for dinner, luncheon, dance, garden party, musical, or whatever she may care to give, is indispensable.

The spacing of the model shown below, the proportion of the words, and the size of the card, are especially good.

The blank which may be used only for dinner:

Mr. and Mrs. Huntington Jones

request the pleasure of

company at dinner

on

at eight o'clock

at Two Thousand Fifth Avenue

(For type and spacing follow model on p. 118.)

Invitations To Receptions And Teas

Invitations to receptions and teas differ from invitations to balls in that the cards on which they are engraved are usually somewhat smaller, the words "At Home" with capital letters are changed to "will be at home" with small letters, and the time is not set at the hour. Also, except on very unusual occasions, a man's name does not appear. The name of the débutante for whom the tea is given is put under that of her mother, and sometimes under that of her sister or the bride of her brother.

Mrs. James Town

Mrs. James Town, junior

Miss Pauline Town

will be at home

On Tuesday the eighth of December

from four until six o'clock

Two Thousand Fifth Avenue.

Mr. Town's name would probably appear with that of his wife if he were an artist, and the reception was given in his studio to view his pictures, or if a reception were given to meet a distinguished guest such as a bishop or a governor, in which case "In honour of the Right Reverend William Powell," or "To meet His Excellency the Governor," is at the top of the invitation.

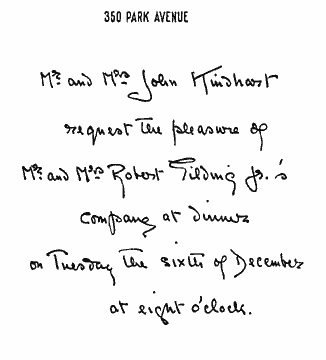

The Formal Invitation Which Is Written

When the formal invitation to dinner or lunch is written instead of engraved, note paper stamped with house or personal device is used. The wording and spacing must follow the engraved models exactly.

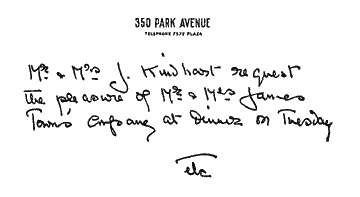

The foregoing example has four faults:

(1) Letters in the third person must follow the prescribed form. This does not. (2) The writing is crowded against the margin. (3) The telephone number should be used only for business and informal notes and letters. (4) The full name John should be used instead of the initial "J." "Mr. and Mrs." is better form than "Mr. & Mrs."

Recalling An Invitation

If for illness or other reason invitations have to be recalled the following forms are correct. They are always printed instead of engraved, there being no time for engraving.

Owing to sudden illness

Mr. and Mrs. John Huntington Smith

are obliged to recall their invitations

for Tuesday the tenth of June.

The form used when the invitation is postponed:

Mr. and Mrs. John Huntington Smith

regret exceedingly

that owing to the illness of Mrs. Smith

their dance is temporarily postponed.

When a wedding is broken off after the invitations have been issued:

Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Nottingham

announce

that the marriage of their daughter

Mary Katharine

and

Mr. Jerrold Atherton

will not take place

Formal Acceptance Or Regret

Acceptances or regrets are always written. An engraved form to be filled in is vulgar—nothing could be in worse taste than to flaunt your popularity by announcing that it is impossible to answer your numerous invitations without the time-saving device of a printed blank. If you have a dozen or more invitations a day, if you have a hundred, hire a staff of secretaries if need be, but answer "by hand."

The formal acceptance to an invitation, whether it is to a dance, wedding breakfast or a ball, is identical:

Mr. and Mrs. Donald Lovejoy

accept with pleasure

Mr. and Mrs. Smith's

kind invitation for dinner

on Monday the tenth of December

at eight o'clock

The formula for regret:

Mr. Clubwin Doe

regrets extremely that a previous engagement

prevents his accepting

Mr. and Mrs. Smith's

kind invitation for dinner

on Monday the tenth of December

or

Mr. and Mrs. Timothy Kerry

regret that they are unable to accept

Mr. and Mrs. Smith's

kind invitation for dinner

on Monday the tenth of December

In accepting an invitation the day and hour must be repeated, so that in case of mistake it may be rectified and prevent one from arriving on a day when one is not expected. But in declining an invitation it is not necessary to repeat the hour.

With the exception of invitations to house-parties, dinners and luncheons, the writing of notes is past. For an informal dance, musical, picnic, for a tea to meet a guest, or for bridge, a lady uses her ordinary visiting card:

To meet

Miss Millicent Gilding

Mrs. John Kindhart

Tues. Jan. 7.

Dancing at 10. o'ck.

350 Park Avenue

or

Wed. Jan. 8.

Bridge at 4. o'ck.

Mrs. John Kindhart

R.s.v.p.

350 Park Avenue

Answers to invitations written on visiting cards are always formally worded in the third person, precisely as though the invitation had been engraved.

Invitations In The Second Person

The informal dinner and luncheon invitation is not spaced according to set words on each line, but is written merely in two paragraphs. Example:

Dear Mrs. Smith:

Will you and Mr. Smith dine with us on Thursday, the seventh of January, at eight o'clock?

Hoping so much for the pleasure of seeing you,

Very sincerely,

Caroline Robinson Town.

The Informal Note Of Acceptance Or Regret

Dear Mrs. Town:

It will give us much pleasure to dine with you on Thursday the seventh, at eight o'clock.

Thanking you for your kind thought of us,

Sincerely yours,

Margaret Smith.

Wednesday.

or

Dear Mrs. Town:

My husband and I will dine with you on Thursday the seventh, at eight o'clock, with greatest pleasure.

Thanking you so much for thinking of us,

Always sincerely,

Margaret Smith.

Dear Mrs. Town:

We are so sorry that we shall be unable to dine with you on the seventh, as we have a previous engagement.

With many thanks for your kindness in thinking of us,

Very sincerely,

Ethel Norman.

Invitation To Country House

To an intimate friend:

Dear Sally:

Will you and Jack (and the baby and nurse, of course) come out the 28th (Friday), and stay for ten days? Morning and evening trains take only forty minutes, and it won't hurt Jack to commute for the weekdays between the two Sundays! I am sure the country will do you and the baby good, or at least it will do me good to have you here.

With much love, affectionately,

Ethel Norman.

To a friend of one's daughter:

Dear Mary:

Will you and Jim come on Friday the first for the Worldly dance, and stay over Sunday? Muriel asks me to tell you that Helen and Dick, and also Jimmy Smith are to be here and she particularly hopes that you will come, too.

The three-twenty from New York is the best train—much. Though there is a four-twenty and a five-sixteen, in case Jim is not able to take the earlier one.

Very sincerely,

Alice Jones.

Confirming a verbal invitation:

Dear Helen:

This note is merely to remind you that you and Dick are coming here for the Worldly dance on the sixth. Mother is expecting you on the three-twenty train, and will meet you here at the station.

Affectionately,

Muriel.

Invitation to a house party at a camp:

Dear Miss Strange:

Will you come up here on the sixth of September and stay until the sixteenth? It would give us all the greatest pleasure. There is a train leaving Broadway Station at 8.03 A.M. which will get you to Dustville Junction at 5 P.M. and here in time for supper.

It is only fair to warn you that the camp is very primitive; we have no luxuries, but we can make you fairly comfortable if you like an outdoor life and are not too exacting. Please do not bring a maid or any clothes that the woods or weather can ruin. You will need nothing but outdoor things: walking boots (if you care to walk), a bathing suit (if you care to swim in the lake), and something comfortable rather than smart for evening (if you care to dress for supper). But on no account bring evening, or any good clothes!

Hoping so much that camping appeals to you and that we shall see you on the evening of the sixth,

Very sincerely yours,

Martha Kindhart.

Custom which has altered many ways and manners has taken away all opprobrium from the message by telephone, and with the exception of those of a very small minority of letter-loving hostesses, all informal invitations are sent and answered by telephone. Such messages, however, follow a prescribed form:

"Is this Lenox 0000? Will you please ask Mr. and Mrs. Smith if they will dine with Mrs. Grantham Jones next Tuesday the tenth at eight o'clock? Mrs. Jones' telephone number is Plaza, one two ring two."

The answer:

"Mr. and Mrs. Huntington Smith regret that they will be unable to dine with Mrs. Jones on Tuesday the tenth, as they are engaged for that evening.

Or

"Will you please tell Mrs. Jones that Mr. and Mrs. Huntington Smith are very sorry that they will be unable to dine with her next Tuesday, and thank her for asking them."

Or

"Please tell Mrs. Jones that Mr. and Mrs. Huntington Smith will dine with her on Tuesday the tenth, with pleasure."

The formula is the same, whether the invitation is to dine or lunch, or play bridge or tennis, or golf, or motor, or go on a picnic.

"Will Mrs. Smith play bridge with Mrs. Grantham Jones this afternoon at the Country Club, at four o'clock?"

"Hold the wire please * * * Mrs. Jones will play bridge, with pleasure at four o'clock."

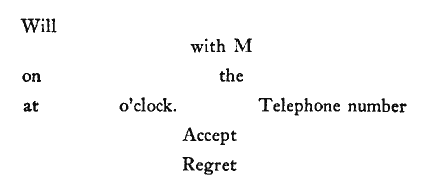

In many houses, especially where there are several grown sons or daughters, a blank form is kept in the pantry:

These slips are taken to whichever member of the family has been invited, who crosses off "regret" or "accept" and hands the slip back for transmission by the butler, the parlor-maid or whoever is on duty in the pantry.

If Mr. Smith and Mrs. Jones are themselves telephoning there is no long conversation, but merely:

Mrs. Jones:

"Is that you Mrs. Smith (or Sarah)? This is Mrs. Jones (or Alice). Will you and your husband (or John) dine with us to-morrow at eight o'clock?"

Mrs. Smith:

"I'm so sorry we can't. We are dining with Mabel."

"We have people coming here."

Invitations to a house party are often as not telephoned:

"Hello, Ethel? This is Alice. Will you and Arthur come on the sixteenth for over Sunday?"

"The sixteenth? That's Friday. We'd love to!"

"Will you take the 3:20 train? etc."

"A gem of a house may be no size at all, but its lines are honest, and its painting and window curtains in good taste ... and its bell is answered promptly by a trim maid with a low voice and quiet, courteous manner." [Page 131.]

CHAPTER XII

THE WELL-APPOINTED HOUSE

Every house has an outward appearance to be made as presentable as possible, an interior continually to be set in order, and incessantly to be cleaned. And for those that dwell within it there are meals to be prepared and served; linen to be laundered and mended; personal garments to be brushed and pressed; and perhaps children to be cared for. There is also a door-bell to be answered in which manners as well as appearance come into play.

Beyond these fundamental necessities, luxuries can be added indefinitely, such as splendor of architecture, of gardening, and of furnishing, with every refinement of service that executive ability can produce. With all this genuine splendor possible only to the greatest establishments, a little house can no more compete than a diamond weighing but half a carat can compete with a stone weighing fifty times as much. And this is a good simile, because the perfect little house may be represented by a corner cut from precisely the same stone and differing therefore merely in size (and value naturally), whereas the house in bad taste and improperly run may be represented by a diamond that is off color and full of flaws; or in some instances, merely a piece of glass that to none but those as ignorant as its owner, for a moment suggests a gem of value.

A gem of a house may be no size at all, but its lines are honest, and its painting and window curtains in good taste. As for its upkeep, its path or sidewalk is beautifully neat, steps scrubbed, brasses polished, and its bell answered promptly by a trim maid with a low voice and quiet courteous manner; all of which contributes to the impression of "quality" evens though it in nothing suggests the luxury of a palace whose opened bronze door reveals a row of powdered footmen.

But the "mansion" of bastard architecture and crude paint, with its brass indifferently clean, with coarse lace behind the plate glass of its golden-oak door, and the bell answered at eleven in the morning by a butler in an ill fitting dress suit and wearing a mustache, might as well be placarded: "Here lives a vulgarian who has never had an opportunity to acquire cultivation." As a matter of fact, the knowledge of how to make a house distinguished both in appearance and in service, is a much higher test than presenting a distinguished appearance in oneself and acquiring presentable manners. There are any number of people who dress well, and in every way appear well, but a lack of breeding is apparent as soon as you go into their houses. Their servants have not good manners, they are not properly turned out, the service is not well done, and the decorations and furnishings show lack of taste and inviting arrangement.

The personality of a house is indefinable, but there never lived a lady of great cultivation and charm whose home, whether a palace, a farm-cottage or a tiny apartment, did not reflect the charm of its owner. Every visitor feels impelled to linger, and is loath to go. Houses without personality are a series of rooms with furniture in them. Sometimes their lack of charm is baffling; every article is "correct" and beautiful, but one has the feeling that the decorator made chalk-marks indicating the exact spot on which each piece of furniture is to stand. Other houses are filled with things of little intrinsic value, often with much that is shabby, or they are perhaps empty to the point of bareness, and yet they have that "inviting" atmosphere, and air of unmistakable quality which is an unfailing indication of high-bred people.

"Becoming" Furniture

Suitability is the test of good taste always. The manner to the moment, the dress to the occasion, the article to the place, the furniture to the background. And yet to combine many periods in one and commit no anachronism, to put something French, something Spanish, something Italian, and something English into an American house and have the result the perfection of American taste—is a feat of legerdemain that has been accomplished time and again.

"The personality of a house is indefinable, but there never lived a lady of great cultivation and charm whose home, whether a palace, a farm-cottage or a tiny apartment, did not reflect the charm of its owner." [Page 132.]

A woman of great taste follows fashion in house furnishing, just as she follows fashion in dress, in general principles only. She wears what is becoming to her own type, and she puts in her house only such articles as are becoming to it.

That a quaint old-fashioned house should be filled with quaint old-fashioned pieces of furniture, in size proportionate to the size of the rooms, and that rush-bottomed chairs and rag-carpets have no place in a marble hall, need not be pointed out. But to an amazing number of persons, proportion seems to mean nothing at all. They will put a huge piece of furniture in a tiny room so that the effect is one of painful indigestion; or they will crowd things all into one corner—so that it seems about to capsize; or they will spoil a really good room by the addition of senseless and inappropriately cluttering objects, in the belief that because they are valuable they must be beautiful, regardless of suitability. Sometimes a room is marred by "treasures" clung to for reasons of sentiment.

The Blindness Of Sentiment

It is almost impossible for any of us to judge accurately of things which we have throughout a lifetime been accustomed to. A chair that was grandmother's, a painting father bought, the silver that has always been on the dining table—are all so part of ourselves that we are sentiment-blind to their defects.

For instance, the portrait of a Colonial officer, among others, has always hung in Mrs. Oldname's dining-room. One day an art critic, whose knowledge was better than his manners, blurted out, "Will you please tell me why you have that dreadful thing in this otherwise perfect room?" Mrs. Oldname, somewhat taken back, answered rather wonderingly: "Is it dreadful?—Really? I have a feeling of affection for him and his dog!"

The critic was merciless. "If you call a cotton-flannel effigy, a dog! And as for the figure, it is equally false and lifeless! It is amazing how any one with your taste can bear looking at it!" In spite of his rudeness, Mrs. Oldname saw that what he said was quite true, but not until the fact had been pointed out to her. Gradually she grew to dislike the poor officer so much that he was finally relegated to the attic. In the same way most of us have belongings that have "always been there" or perhaps "treasures" that we love for some association, which are probably as bad as can be, to which habit has blinded us, though we would not have to be told of their hideousness were they seen by us in the house of another.

It is not to be expected that all people can throw away every esthetically unpleasing possession, with which nearly every house twenty-five years ago was filled, but those whose pocket-book and sentiment will permit, would add greatly to the beauty of their houses by sweeping the bad into the ash can! Far better have stone-ware plates that are good in design than expensive porcelain that is horrible in decoration.

The only way to determine what is good and what is horrible is to study what is good in books, in museums, or in art classes in the universities, or even by studying the magazines devoted to decorative art.

Be very careful though. Do not mistake modern eccentricities for "art." There are frightful things in vogue to-day—flamboyant colors, grotesque, triangular and oblique designs that can not possibly be other than bad, because aside from striking novelty, there is nothing good about them. By no standard can a room be in good taste that looks like a perfume manufacturer's phantasy or a design reflected in one of the distorting mirrors that are mirth-provokers at county fairs.

To Determine An Object's Worth

In buying an article for a house one might formulate for oneself a few test questions:

First, is it useful? Anything that is really useful has a reason for existence.

Second, has it really beauty of form and line and color?

(Texture is not so important.) Or is it merely striking, or amusing?

Third, is it entirely suitable for the position it occupies?

Fourth, if it were eliminated would it be missed? Would something else look as well or better, in its place? Or would its place look as well empty? A truthful answer to these questions would at least help in determining its value, since an article that failed in any of them could not be "perfect."

Fashion affects taste—it is bound to. We abominate Louis the Fourteenth and Empire styles at the moment, because curves and super-ornamentation are out of fashion; whether they are really bad or not, time alone can tell. At present we are admiring plain silver and are perhaps exacting that it be too plain? The only safe measure of what is good, is to choose that which has best endured. The "King" and the "Fiddle" pattern for flat silver, have both been in use in houses of highest fashion ever since they were designed, so that they, among others, must have merit to have so long endured.

In the same way examples of old potteries and china and glass, at present being reproduced, are very likely good, because after having been for a century or more in disuse, they are again being chosen. Perhaps one might say that the "second choice" is "proof of excellence."

Service

The subject of furnishings is however the least part of this chapter—appointments meaning decoration being of less importance (since this is not a book on architecture or decoration!), than appointments meaning service.

But before going into the various details of service, it might be a good moment to speak of the unreasoning indignity cast upon the honorable vocation of a servant.

There is an inexplicable tendency, in this country only, for working people in general to look upon domestic service as an unworthy, if not altogether degrading vocation. The cause may perhaps be found in the fact that this same scorning public having for the most part little opportunity to know high-class servants, who are to be found only in high-class families, take it for granted that ignorant "servant girls" and "hired men" are representative of their kind. Therefore they put upper class servants in the same category—regardless of whether they are uncouth and illiterate, or persons of refined appearance and manner who often have considerable cultivation, acquired not so much at school as through the constant contact with ultra refinement of surroundings, and not infrequently through the opportunity for world-wide travel.

And yet so insistently has this obloquy of the word "servant" spread that every one sensitive to the feelings of others avoids using it exactly as one avoids using the word "cripple" when speaking to one who is slightly lame. Yet are not the best of us "servants" in the Church? And the highest of us "servants" of the people and the State?

To be a slattern in a vulgar household is scarcely an elevated employment, but neither is working in a sweat-shop, or belonging to a calling that is really degraded; which is otherwise about all that equal lack of ability would procure. On the other hand, consider the vocation of a lady's maid or "courier" valet and compare the advantages these enjoy (to say nothing of their never having to worry about overhead expenses), with the opportunities of those who have never been out of the "factory" or the "store" or further away than the adjoining town in their lives. As for a nurse, is there any vocation more honorable? No character in E.F. Benson's "Our Family Affairs" is more beautiful or more tenderly drawn than that of "Beth," who was not only nurse to the children of the Archbishop of Canterbury but one of the most dearly beloved of the family's members—her place was absolutely next to their mother's in the very heart of the household always.

Two years ago, Anna, who had for a lifetime been Mrs. Gilding's personal maid, died. Every engagement of that seemingly frivolous family was cancelled, even the invitations for their ball. Not one of the family but mourned for what she truly was, their humble but nearest friend. Would it have been so much better, so much more dignified, for these two women, who lived long useful years in closest association with every cultivating influence of life, to have lived on in their native villages and worked in a factory, or to have had a little store of their own? Does this false idea of dignity—since it is false—go so far as that?

How Many Servants For Correct Service?

It stands to reason that one may expect more perfect service from a "specialist" than from one whose functions are multiple. But small houses that have a double equipment—meaning an alternate who can go in the kitchen, and two for the dining-room—can be every bit as well run, so far as essentials go, as the palaces of the Gildings and the Worldlys, though of course not with the same impressiveness. But good service is badly handicapped if, when the waitress goes out, there is no one to open the door, or when the cook goes out, there is no one to prepare a meal.

For what one might call "complete" service, (meaning service that is adequate for constant entertaining and can stand comparison with the most luxurious establishments,) three are the minimum—a cook, a butler (or waitress) and a housemaid. The reason why luncheons and dinners can not be "perfectly" given with a waitress alone is because two persons are necessary for the exactions of modern standards of service. Yet one alone can, on occasion, manage very well, if attention is paid to ordering an especial menu for single-handed service—described on page 233. Aside from the convenience of a second person in the dining-room, a house can not be run very comfortably and smoothly without alternating shifts in staying in and going out. The waitress being on "duty" to answer bell and telephone and serve tea one afternoon, and the housemaid taking her place the next. They also alternate in going out every other evening after dinner.

It should be realized that above the number necessary for essentials, each additional chambermaid, parlor-maid, footman, scullery maid or useful man, is made necessary by the size of the house and by the amount of entertaining usual, rather than (as is often supposed) for the mere reason of show. The seemingly superfluous number of footmen at Golden Hall and Great Estates are, aside from standing on parade at formal parties, needed actually to do the immense amount of work that houses of such size entail; whereas a small apartment can be fairly well looked after by one alone.

All house employees and details of their several duties, manners, and appearances, are enumerated below. Beginning with the greatest and most complicated establishments possible, the employee of highest rank is:

The Secretary Who Is Also Companion

The position of companion, which is always one of social equality with her employer, exists only when the lady of the house is an invalid, or very elderly, or a widow, or a young girl. (In the latter case the "companion" is a "chaperon.")

Her secretarial duties consist in writing impersonal letters and notes and probably paying bills; she may have occasional invitations to send out, and to answer, though a lady needing a companion is not apt to be greatly interested in social activities. The companion never performs the services of a maid—but she occasionally does the housekeeping. Otherwise her duties can not very well be set down, because they vary with individual requirements. One lady likes continually to travel and merely wants a companion, (usually a poor relative or friend) to go with her. Another who is a semi-invalid never leaves her room, and the duties of her companion are almost those of a trained nurse. The average requirement is in being personally agreeable, tactful, intelligent, and—companionable!

A companion dresses as any other lady does; according to the occasion, her personal taste, her age, and her means.

Varied Social Standing Of The Private Secretary

The private secretary to a diplomat, since, he must first pass the diplomatic examination in order to qualify, is invariably a young man of education, if not of birth, and his social position is always that of a member of his "chief's" family.

The position of an ordinary private secretary is sometimes that of an upper servant, or, on the other hand, his own social position may be much higher than that of his employer. A secretary who either has position of his own or is given position by his employer, is in every way treated as a member of the family; he is present at all general entertainments; and quite as often as not at lunches and dinners. The duties of a private secretary are naturally to attend to all correspondence, take shorthand notes of speeches or conversations, file papers and documents and in every way serve as extra eyes and hands and supplementary brain for his employer.

The Social Secretary

The position of social secretary is an entirely clerical one, and never confers any "social privileges" unless the secretary is also "companion."

Her duties are to write all invitations, acceptances, and regrets; keep a record of every invitation received and every one sent out, and to enter in an engagement book every engagement made for her employer, whether to lunch, dinner, to be fitted, or go to the dentist. She also writes all impersonal notes, takes longer letters in shorthand, and writes others herself after being told their purport. She also audits all bills and draws the checks for them, the checks are filled in and then presented to her employer to be signed, after which they are put in their envelopes, sealed and sent. When the receipted bills are returned, the secretary files them according to her own method, where they can at any time be found by her if needed for reference. In many cases it is she (though it is most often the butler) who telephones invitations and other messages.

Occasionally a social secretary is also a social manager; devises entertainments and arranges all details such as the decorations of the house for a dance, or a programme of entertainment following a very large dinner. The social secretary very rarely lives in the house of her employer; more often than not she goes also to one or two other houses—since there is seldom work enough in one to require her whole time.

Miss Brisk, who is Mrs. Gilding's secretary, has little time for any one else. She goes every day for from two to sometimes eight or nine hours in town, and at Golden Hall lives in the house. Usually a secretary can finish all there is to do in an average establishment in about an hour, or at most two, a day, with the addition of five or six hours on two or three other days each month for the paying of bills.

Supposing she takes three positions; she goes to Mrs. A. from 8.30 to 10 every day, and for three extra hours on the 10th and 11th of every month. To Mrs. B. from 10.30 to 1 (her needs being greater) and for six extra hours on the 12th, 13th and 14th of every month. And to Mrs. C. every day at 3 o'clock for an indefinite time of several hours or only a few minutes.

Her dress is that of any business woman. Conspicuous clothes are out of keeping as they would be out of keeping in an office; which, however, is no reason why she should not be well dressed. Well-cut tailor-made suits are the most appropriate with a good-looking but simple hat; as good shoes as she can possibly afford, and good gloves and immaculately clean shirt waists, represent about the most dignified and practical clothes. But why describe clothes! Every woman with good sense enough to qualify as a secretary has undoubtedly sense enough to dress with dignity.