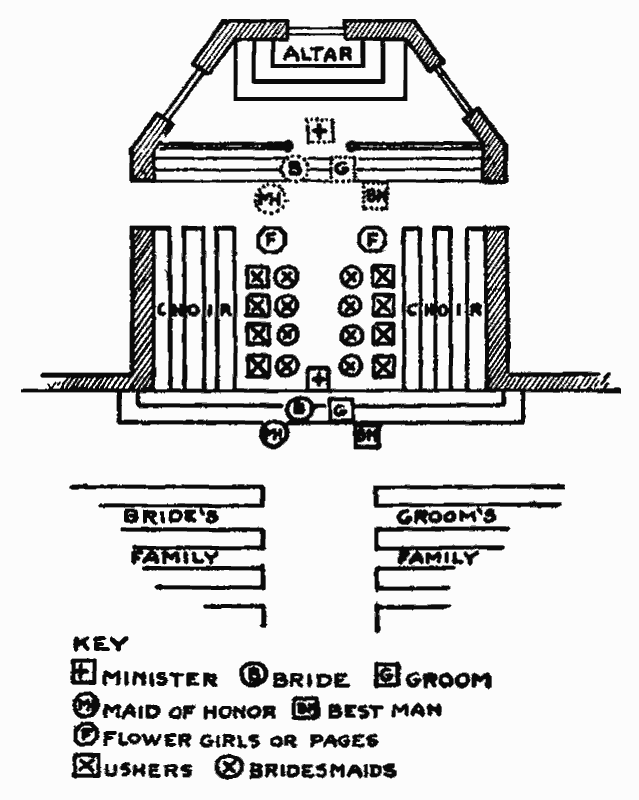

Or in a big church they go up farther, some of them lining the steps, or all of them in front of the choir stalls. The bridesmaids also divide, half on either side, and always stand in front of the ushers. The maid of honor's place is on the left at the foot of the steps, exactly opposite the best man. Flower girls and pages are put above or below the bridesmaids wherever it is thought "the picture" is best.

The grouping of the ushers and bridesmaids in the chancel or lining the steps also depends upon their number and the size of the church. In any event, the bridesmaids stand in front of the ushers; half of them on the right and half on the left. They never stand all on the bride's side, and the ushers on the groom's.

The clergyman who is to perform the marriage comes into the chancel from the vestry. At a few paces behind him follows the groom, who in turn is followed by the best man. The groom stops at the foot of the chancel steps and takes his place at the right, as indicated in the accompanying diagram. His best man stands directly behind him. The ushers and bridesmaids always pass in front of him and take their places as noted above. When the bride approaches, the groom takes only a step to meet her.

A more effective greeting of the bride is possible if the door of the vestry opens into the chancel so that on following the clergyman, the groom finds himself at the top instead of the foot of the chancel steps. He goes forward to the right-hand side (his left), his best man behind him, and waits where he is until his bride approaches, when he goes down the steps to meet her—which is perhaps more gallant than to stand at the head of the aisle, and wait for her to join him.

The real bride watches carefully how the pseudo bride takes her left hand from her father's arm, shifts her fan, or whatever represents her bouquet, from her right hand to her left, and gives her right hand to the groom. In the proper maneuver the groom takes her right hand in his own right hand and draws it through his left arm, at the same time turning toward the chancel. If the service is undivided, and all of it is to be at the altar, this is necessary as the bride always goes up to the altar leaning on the arm of the groom.

If, however, the betrothal is to be read at the foot of the chancel (which is done at most weddings now) he may merely take her hand in his left one and stand as they are.

The Organist's Cue

The organist stops at the moment the bride and groom have assumed their places. That is the cue to the organist as to the number of bars necessary for the procession. After the procession has practised "marching" two or three times, everything ought to be perfect. The organist, having counted up the necessary bars of music, can readily give the leading ushers their "music cue"—so that they can start on the measure that will allow the procession and the organ to end together. The organist can, and usually does, stop off short, but there is a better finish if the bride's giving her hand to the groom and taking the last step that brings her in front of the chancel is timed so as to fall precisely on the last bars of the processional.

No words of the service are ever rehearsed, although all the "positions" to be taken are practised.

The pseudo bride takes the groom's left arm and goes slowly up the steps to the altar.

The best man follows behind and to the right of the groom, and the maid of honor (or "first" bridesmaid) leaves her companions and advances behind and to the left of the bride. The pseudo bride (in pantomime) gives her bouquet to the maid of honor; the best man (also in pantomime) hands the ring to the groom, this merely to see that they are at a convenient distance for the services they are to perform. The recessional is played, and the procession goes out in reversed order. Bride and groom first, then bridesmaids, then ushers, again all taking pains to fall into step with the leaders.

On no account must the bridesmaids walk either up or down the aisle with the ushers! Once in a while the maid of honor takes the arm of the best man and together they follow the bride and groom out of the church. But it gives the impression of a double wedding and spoils the picture.

Obligations Of The Bridegroom

In order that the first days of their life together may be as perfect as possible, the groom must make preparations for the wedding trip long ahead of time, so that best accommodations can be reserved. If they are to stop first at a hotel in their own city, or one near by, he should go days or even weeks in advance and personally select the rooms. It is much better frankly to tell the proprietor, or room clerk, at the same time asking him to "keep the secret." Everyone takes a friendly interest in a bridal couple, and the chances are that the proprietor will try to reserve the prettiest rooms in the house, and give the best service.

If their first stop is to be at a distance, then he must engage train seats or boat stateroom, and write to the hotel of their destination far enough in advance to receive a written reply, so that he may be sure of the accommodations they will find.

Expense Of The Wedding Trip

Just as it is contrary to all laws of etiquette for the bride to accept any part of her trousseau or wedding reception from the groom, so it is unthinkable for the bride to defray the least fraction of the cost of the wedding journey, no matter though she have millions in her own right, and he be earning ten dollars a week. He must save up his ten dollars as long as necessary, and the trip can be as short as they like, but convention has no rule more rigid than that the wedding trip shall be a responsibility of the groom.

There are two modifications of this rule: a house may be put at their disposal by a member of her family, or, if she is a widow, they may go to one of her own, provided it is not one occupied by her with her late husband. It is also quite all right for them to go away in a motor belonging to her, but driven by him, and all garage expenses belong to him; or if her father or other member of the family offers the use of a yacht or private railway car, the groom may accept but he should remember that the incidental and unavoidable expense of such a "gift" is sometimes greater than the cost of railway tickets.

Buying The Wedding Ring

It is quite usual for the bride to go with the groom when he buys the wedding ring, the reason being that as it stays for life on her finger, she should be allowed to choose the width and weight she likes and the size she finds comfortable.

The Groom's Present To The Bride

He is a very exceptional and enviable man who is financially able to take his fiancée to the jeweler's and let her choose what she fancies. Usually the groom buys the handsomest ornament he can afford—a string of pearls if he has great wealth, or a diamond pendant, brooch or bracelet, or perhaps only the simplest bangle or charm—but whether it is of great or little worth, it must be something for her personal adornment.

Further Obligations Of The Groom

Gifts must be provided for his best man and ushers, as well as their ties, gloves and boutonnières, a bouquet for his bride, and the fee for the clergyman, which may be a ten dollar gold piece or one or two new one hundred dollar bills, according to his wealth and the importance of the wedding. Whatever the amount, it is enclosed in an envelope and taken in charge by the best man who hands it to the clergyman in his vestry-room immediately after the ceremony.

CHAPTER XXII

THE DAY OF THE WEDDING

No one is busier than the best man on the day of the wedding. His official position is a cross between trained nurse, valet, general manager and keeper.

Bright and early in the morning he hurries to the house of the groom, generally before the latter is up. Very likely they breakfast together; in any event, he takes the groom in charge precisely as might a guardian. He takes note of his patient's general condition; if he is normal and "fit," so much the better. If he is "up in the air" or "nervous" the best man must bring him to earth and jolly him along as best he can.

Best Man As Expressman

His first actual duty is that of packer and expressman; he must see that everything necessary for the journey is packed, and that the groom does not absent-mindedly put the furnishings of his room in his valise and leave his belongings hanging in the closet. He must see that the clothes the groom is to "wear away" are put into a special bag to be taken to the house of the bride (where he, as well as she, must change from wedding into traveling clothes). The best man becomes expressman if the first stage of the wedding journey is to be to a hotel in town. He puts all the groom's luggage into his own car or a taxi, drives to the bride's house, carries the bag with the groom's traveling suit in it to the room set aside for his use—usually the dressing-room of the bride's father or the bedroom of her brother. He then collects, according to pre-arrangement, the luggage of the bride and drives with the entire equipment of both bride and groom to the hotel where rooms have already been engaged, sees it all into the rooms, and makes sure that everything is as it should be. If he is very thoughtful, he may himself put flowers about the rooms. He also registers for the newly-weds, takes the room key, returns to the house of the groom, gives him the key and assures him that everything at the hotel is in readiness. This maneuver allows the young couple when they arrive to go quietly to their rooms without attracting the notice of any one, as would be the case if they arrived with baggage and were conspicuously shown the way by a bell-boy whose manner unmistakably proclaims "Bride and Groom!"

Or, if they are going at once by boat or train, the best man takes the baggage to the station, checks the large pieces, and fees a porter to see that the hand luggage is put in the proper stateroom or parlor car chairs. If they are going by automobile, he takes the luggage out to the garage and personally sees that it is bestowed in the car.

Best Man As Valet

His next duty is that of valet. He must see that the groom is dressed and ready early, and plaster him up if he cuts himself shaving. If he is wise in his day he even provides a small bottle of adrenaline for just such an accident, so that plaster is unnecessary and that the groom may be whole. He may need to find his collar button or even to point out the "missing" clothes that are lying in full view. He must also be sure to ask for the wedding ring and the clergyman's fee, and put them in his own waistcoat pocket. A very careful best man carries a duplicate ring, in case of one being lost during the ceremony.

Best Man As Companion-in-ordinary

With the bride's and groom's luggage properly bestowed, the ring and fee in his pocket, the groom's traveling clothes at the bride's house, the groom in complete wedding attire, and himself also ready, the best man has nothing further to do but be gentleman-in-waiting to the groom until it is time to escort him to the church, where he becomes chief of staff.

Meanwhile, if the wedding is to be at noon, dawn will not have much more than broken before the house—at least below stairs—becomes bustling.

Even if the wedding is to be at four o'clock, it will still be early in the morning when the business of the day begins. But let us suppose it is to be at noon; if the family is one that is used to assembling at an early breakfast table, it is probable that the bride herself will come down for this last meal alone with her family. They will, however, not be allowed to linger long at the table. The caterer will already be clamoring for possession of the dining-room—the florist will by that time already have dumped heaps of wire and greens into the middle of the drawing-room, if not beside the table where the family are still communing with their eggs. The door-bell has long ago begun to ring. At first there are telegrams and special delivery letters, then as soon as the shops open, come the last-moment wedding presents, notes, messages and the insistent clamor of the telephone.

Next, excited voices in the hall announce members of the family who come from a distance. They all want to kiss the bride, they all want rooms to dress in, they all want to talk. Also comes the hairdresser, to do the bride's or her mother's or aunt's or grandmother's hair, or all of them; the manicure, the masseuse—any one else that may have been thought necessary to give final beautifying touches to any or all of the female members of the household. The dozen and one articles from the caterer are meantime being carried in at the basement door; made dishes, and dishes in the making, raw materials of which others are to be made; folding chairs, small tables, chinaware, glassware, napery, knives, forks and spoons—it is a struggle to get in or out of the kitchen or area door.

The bride's mother consults the florist for the third and last time as to whether the bridal couple had not better receive in the library because of the bay window which lends itself easily to the decoration of a background, and because the room, is, if anything, larger than the drawing-room. And for the third time, the florist agrees about the advantage of the window but points out that the library has only one narrow door and that the drawing-room is much better, because it has two wide ones and guests going into the room will not be blocked in the doorway by others coming out.

The best man turns up and wants the bride's luggage.

The head usher comes to ask whether the Joneses to be seated in the fourth pew are the tall dark ones or the blond ones, and whether he had not better put some of the Titheringtons who belong in the eighth pew also in the seventh, as there are nine Titheringtons and the Eminents in the seventh pew are only four.

A bridesmaid-elect hurries up the steps, runs into the best man carrying out the luggage; much conversation and giggling and guessing as to where the luggage is going. Best man very important, also very noble and silent. Bridesmaid shrugs her shoulders, dashes up to the bride's room and dashes down again.

More presents arrive. The furniture movers have come and are carting lumps of heaviness up the stairs to the attic and down the stairs to the cellar. It is all very like an ant-hill. Some are steadily going forward with the business in hand, but others who have become quite bewildered, seem to be scurrying aimlessly this way and that, picking something up only to put it down again.

The Drawing-Room

Here, where the bride and groom are to receive, one can not tell yet what the decoration is to be. Perhaps it is a hedged-in garden scene, a palm grove, a flowering recess, a screen and canopy of wedding bells—but a bower of foliage of some sort is gradually taking shape.

The Dining-Room

The dining-room, too, blossoms with plants and flowers. Perhaps its space and that of a tent adjoining is filled with little tables, or perhaps a single row of camp chairs stands flat against the walls, and in the center of the room, the dining table pulled out to its farthest extent, is being decked with trimmings and utensils which will be needed later when the spaces left at intervals for various dishes shall be occupied. Preparation of these dishes is meanwhile going on in the kitchen.

The Kitchen

The caterer's chefs in white cook's caps and aprons are in possession of the situation, and their assistants run here and there, bringing ingredients as they are told; or perhaps the caterer brings everything already prepared, in which case the waiters are busy unpacking the big tin boxes and placing the bain-marie (a sort of fireless cooker receptacle in a tank of hot water) from which the hot food is to be served. Huge tubs of cracked ice in which the ice cream containers are buried are already standing in the shade of the areaway or in the back yard.

Last Preparations

Back again in the drawing-room, the florist and his assistants are still tying and tacking and arranging and adjusting branches and garlands and sheaves and bunches, and the floor is a litter of twigs and strings and broken branches. The photographer is asking that the central decoration be finished so he can group his pictures, the florist assures him that he is as busy as possible.

The house is as cold as open windows can make it, to keep the flowers fresh, and to avoid stuffiness. The door-bell continues its ringing, and the parlor maid finds herself a contestant in a marathon, until some one decides that card envelopes and telegrams had better be left in the front hall.

A first bridesmaid arrives. She at least is on time. All decoration activity stops while she is looked at and admired. Panic seizes some one! The time is too short, nothing will be ready! Some one else says the bridesmaid is far too early, there is no end of time.

Upstairs everyone is still dressing. The father of the bride (one would suppose him to be the bridegroom at least) is trying on most of his shirts, the floor strewn with discarded collars! The mother of the bride is hurrying into her wedding array so as to be ready for any emergency, as well as to superintend the finishing touches to her daughter's dress and veil.

The Wedding Dress

Everyone knows what a wedding dress is like. It may be of any white material, satin, brocade, velvet, chiffon or entirely of lace. It may be embroidered in pearls, crystals or silver; or it may be as plain as a slip-cover—anything in fact that the bride fancies, and made in whatever fashion or period she may choose.

As for her veil in its combination of lace or tulle and orange blossoms, perhaps it is copied from a head-dress of Egypt or China, or from the severe drapery of Rebecca herself, or proclaim the knowing touch of the Rue de la Paix. It may have a cap, like that of a lady in a French print, or fall in clouds of tulle from under a little wreath, such as might be worn by a child Queen of the May.

The origin of the bridal veil is an unsettled question.

Roman brides wore "yellow veils," and veils were used in the ancient Hebrew marriage ceremony. The veil as we use it may be a substitute for the flowing tresses which in old times fell like a mantle modestly concealing the bride's face and form; or it may be an amplification of the veil which medieval fashion added to every head-dress.

In olden days the garland rather than the veil seems to have been of greatest importance. The garland was the "coronet of the good girl," and her right to wear it was her inalienable attribute of virtue.

Very old books speak of three ornaments that every virtuous bride must wear, "a ring on her finger, a brooch on her breast and a garland on her head."

A bride who had no dowry of gold was said nevertheless to bring her husband great treasure, if she brought him a garland—in other words, a virtuous wife.

At present the veil is usually mounted by a milliner on a made foundation, so that it need merely be put on—but every young girl has an idea of how she personally wants her wedding veil and may choose rather to put it together herself or have it done by some particular friend, whose taste and skill she especially admires.

If she chooses to wear a veil over her face up the aisle and during the ceremony, the front veil is always a short separate piece about a yard square, gathered on an invisible band, and pinned with a hair pin at either side, after the long veil is arranged. It is taken off by the maid of honor when she gives back the bride's bouquet at the conclusion of the ceremony.

The face veil is a rather old-fashioned custom, and is appropriate only for a very young bride of a demure type; the tradition being that a maiden is too shy to face a congregation unveiled, and shows her face only when she is a married woman.

Some brides prefer to remove their left glove by merely pulling it inside out at the altar. Usually the under seam of the wedding finger of her glove is ripped for about two inches and she need only pull the tip off to have the ring put on. Or, if the wedding is a small one, she wears no gloves at all.

Brides have been known to choose colors other than white. Cloth of silver is quite conventional and so is very deep cream, but cloth of gold suggests the habiliment of a widow rather than that of a virgin maid—of which the white and orange blossoms, or myrtle leaf, are the emblems.

If a bride chooses to be married in traveling dress, she has no bridesmaids, though she often has a maid of honor. A "traveling" dress is either a "tailor made" if she is going directly on a boat or train, or a morning or afternoon dress—whatever she would "wear away" after a big wedding.

But to return to our particular bride; everyone seemingly is in her room, her mother, her grandmother, three aunts, two cousins, three bridesmaids, four small children, two friends, her maid, the dressmaker and an assistant. Every little while, the parlor-maid brings a message or a package. Her father comes in and goes out at regular intervals, in sheer nervousness. The rest of the bridesmaids gradually appear and distract the attention of the audience so that the bride has moments of being allowed to dress undisturbed. At last even her veil is adjusted and all present gasp their approval: "How sweet!" "Dearest, you are too lovely!" and "Darling, how wonderful you look!"

Her father reappears: "If you are going to have the pictures taken, you had better all hurry!"

"Oh, Mary," shouts some one, "what have you on that is

Something old, something new,

Something borrowed, something blue,

And a lucky sixpence in your shoe!"

"Let me see," says the bride, "'old,' I have old lace; 'new,' I have lots of new! 'Borrowed,' and 'blue'?" A chorus of voices: "Wear my ring," "Wear my pin," "Wear mine! It's blue!" and some one's pin which has a blue stone in it, is fastened on under the trimming of her dress and serves both needs. If the lucky sixpence (a dime will do) is produced, she must at least pay discomfort for her "luck."

Again some one suggests the photographer is waiting and time is short. Having pictures taken before the ceremony is a dull custom, because it is tiring to sit for one's photograph at best, and to attempt anything so delaying as posing at the moment when the procession ought to be starting, is as trying to the nerves as it is exhausting, and more than one wedding procession has consisted of very "dragged out" young women in consequence.

At a country wedding it is very easy to take the pictures out on the lawn at the end of the reception and just before the bride goes to dress. Sometimes in a town house, they are taken in an up-stairs room at that same hour; but usually the bride is dressed and her bridesmaids arrive at her house fully half an hour before the time necessary to leave for the church, and pictures of the group are taken as well as several of the bride alone—with special lights—against the background where she will stand and receive.

Whether the pictures are taken before the wedding or after, the bridesmaids always meet at the house of the bride, where they also receive their bouquets. When it is time to go to the church, there are several carriages or motors drawn up at the house. The bride's mother drives away in the first, usually alone, or she may, if she chooses, take one or two bridesmaids in her car, but she must reserve room for her husband who will return from church with her. The maid of honor, bridesmaids and flower girls go in the next vehicles, which may be their own or else are supplied by the bride's family; and last of all, comes the bride's carriage, which always has a wedding appearance. If it is a brougham, the horses' headpieces are decorated with white flowers and the coachman wears a white boutonnière; if it is a motor, the chauffeur wears a small bunch of white flowers on his coat, and white gloves, and has all the tires painted white to give the car a wedding appearance. The bride drives to the church with her father only. Her carriage arrives last of the procession, and stands without moving, in front of the awning, until she and her husband (in place of her father) return from the ceremony and drive back to the house for the breakfast or reception.

If she has no father, this part is taken by an uncle, a brother, a cousin, her guardian, or other close male connection of her family.

If it should happen that the bride has neither father nor very near male relative, or guardian, she walks up the aisle alone. At the point in the ceremony when the clergyman asks who gives the bride, if the betrothal is read at the chancel steps, her mother goes forward and performs the office in exactly the same way that her father would have done.

If the entire ceremony is at the altar, the mother merely stays where she is standing in her proper place at the end of the first pew on the left, and says very distinctly, "I do."

Meanwhile, about an hour before the time for the ceremony, the ushers arrive at the church and the sexton turns his guardianship over to them. They leave their hats in the vestry, or coat room. Their boutonnières, sent by the groom, should be waiting in the vestibule. They should be in charge of a boy from the florist's, who has nothing else on his mind but to see that they are there, that they are fresh and that the ushers get them. Each man puts one in his buttonhole, and also puts on his gloves. The head usher decides (or the groom has already told them) to which ushers are apportioned the center, and to which the side aisles. If it is a big church with side aisles and gallery, and there are only six ushers, four will be put in the center aisle, and two in the side. Guests who choose to sit up in the gallery find places for themselves.

Often, at a big wedding, the sexton or one of his assistants guards the entrance to the gallery and admission is reserved by cards for the employees of both families, but usually the gallery is open to those who care to go up. An usher whose "place" is in the side aisle may escort occasional personal friends of his own down the center aisle if he happens to be unoccupied at the moment of their entrance. Those of the ushers who are the most likely to recognize the various close friends and members of each family are invariably detailed to the center aisle. A brother of the bride, for instance, is always chosen for this aisle because he is best fitted to look out for his own relatives and to place them according to their near or distant kinship. A second usher should be either a brother of the groom or a near relative who would be able to recognize the family and close friends of the groom.

The first six to twenty pews on both sides of the center aisle are fenced off with white ribbons into a reserved enclosure. The parents of the bride always sit in the first pew on the left (facing the chancel); the parents of the groom always sit in the first pew on the right. The right hand side of the church is the groom's side always, the left is that of the bride.

A Church Wedding

"In the city or country the church is decorated with masses of flowers, greens and sprays of flowers at the ends of the six to twenty reserved pews." [Page 354.]

It is the duty of the ushers to show all guests to their places. An usher offers his arm to each lady as she arrives, whether he knows her personally or not. If the vestibule is very crowded and several ladies are together, he sometimes gives his arm to the older and asks the others to follow. But this is not done unless the crowd is great and the time short.

If the usher thinks a guest belongs in front of the ribbons though she fails to present her card, he always asks at once "Have you a pew number?" If she has, he then shows her to her place. If she has none, he asks whether she prefers to sit on the bride's side or the groom's and gives her the best seat vacant in the unreserved part of the church. He generally makes a few polite remarks as he takes her up the aisle. Such as:

"I am so sorry you came late, all the good seats are taken further up." Or "Isn't it lucky they have such a beautiful day?" or "Too bad it is raining." Or, perhaps the lady is first in making a similar remark or two to him.

Whatever conversation there is, is carried on in a low voice, not, however, whispered or solemn. The deportment of the ushers should be natural but at the same time dignified and quiet in consideration of the fact that they are in church. They must not trot up and down the aisles in a bustling manner; yet they must be fairly agile, as the vestibule is packed with guests who have all to be seated as expeditiously as possible.

The guests without reserved cards should arrive first in order to find good places; then come the reserved seat guests; and lastly, the immediate members of the families, who all have especial places in the front pews held for them.

It is not customary for one who is in deep mourning to go to a wedding, but there can be little criticism of an intimate friend who takes a place in the gallery of the church from which she can see the ceremony and yet be apart from the wedding guests. At a wedding that is necessarily small because of mourning, the women of the family usually lay aside black for that one occasion and wear white.

In Front of the Ribbons

There are two ways in which people "in front of the ribbons" are seated. The less efficient way is by means of a typewritten list of those for whom seats are reserved and of the pews in which they are to be seated, given to each usher, who has read it over for each guest who arrives at the church. From every point of view, the typewritten list is bad; first, it wastes time, and as everyone arrives at the same moment, and every lady is supposed to be taken personally up the aisle "on the arm" of an usher, the time consumed while each usher looks up each name on several gradually rumpling or tearing sheets of paper is easily imagined. Besides which, one who is at all intimate with either family can not help feeling in some degree slighted when, on giving one's name, the usher looks for it in vain.

The second, and far better method, is to have a pew card sent, enclosed with the wedding invitation, or an inscribed visiting card sent by either family. A guest who has a card with "Pew No. 12" on it, knows, and the usher knows, exactly where she is to go. Or if she has a card saying "Reserved" or "Before the ribbons" or any special mark that means in the reserved section but no especial pew, the usher puts her in the "best position available" behind the first two or three numbered rows that are saved for the immediate family, and in front of the ribbons marking the reserved enclosure.

It is sometimes well for the head usher to ask the bride's mother if she is sure she has allowed enough pews in the reserved section to seat all those with cards. Arranging definite seat numbers has one disadvantage; one pew may have every seat occupied and another may be almost empty. In that case an usher can, just before the procession is to form, shift a certain few people out of the crowded pews into the others. But it would be a breach of etiquette for people to re-seat themselves, and no one should be seated after the entrance of the bride's mother.

Meanwhile, about fifteen minutes before the wedding hour, the groom and his best man—both in morning coats, top-hats, boutonnières and white buckskin (but remember not shiny) gloves, walk or drive to the church and enter the side door which leads to the vestry. There they sit, or in the clergyman's study, until the sexton or an usher comes to say that the bride has arrived.

The Perfectly Managed Wedding

At a perfectly managed wedding, the bride arrives exactly one minute (to give a last comer time to find place) after the hour. Two or three servants have been sent to wait in the vestibule to help the bride and bridesmaids off with their wraps and hold them until they are needed after the ceremony. The groom's mother and father also are waiting in the vestibule. As the carriage of the bride's mother drives up, an usher goes as quickly as he can to tell the groom, and any brothers or sisters of the bride or groom, who are not to take part in the wedding procession and have arrived in their mother's carriage, are now taken by ushers to their places in the front pews. The moment the entire wedding party is at the church, the doors between the vestibule and the church are closed. No one is seated after this, except the parents of the young couple. The proper procedure should be carried out with military exactness, and is as follows:

The groom's mother goes down the aisle on the arm of the head usher and takes her place in the first pew on the right; the groom's father follows alone, and takes his place beside her; the same usher returns to the vestibule and immediately escorts the bride's mother; he should then have time to return to the vestibule and take his place in the procession. The beginning of the wedding march should sound just as the usher returns to the head of the aisle. To repeat: No other person should be seated after the mother of the bride. Guests who arrive later must stand in the vestibule or go into the gallery.

The sound of the music is also the cue for the clergyman to enter the chancel, followed by the groom and his best man. The two latter wear gloves but have left their hats and sticks in the vestry-room.

The groom stands on the right hand side at the head of the aisle, but if the vestry opens into the chancel, he sometimes stands at the top of the first few steps. He removes his right glove and holds it in his left hand. The best man remains always directly back and to the right of the groom, and does not remove his glove.

Here Comes The Bride

The description of the procession is given in detail on a preceding page in the "Wedding Rehearsal" section.

Starting on the right measure and keeping perfect time, the ushers come, two by two, four paces apart; then the bridesmaids (if any) at the same distance exactly; then the maid of honor alone; then the flower girls (if any); then, at a double distance, the bride on her father's right arm. She is dressed always in white, with a veil of lace or tulle. Usually she carries a bridal bouquet of white flowers, either short, or with streamers (narrow ribbons with little bunches of blossoms on the end of each) or trailing vines, or maybe she holds a long sheaf of stiff flowers such as lilies on her arm. Or perhaps she carries a prayer book instead of a bouquet.

The Groom Comes Forward To Meet The Bride

As the bride approaches, the groom waits at the foot of the steps (unless he comes down the steps to meet her). The bride relinquishes her father's arm, changes her bouquet from her right to her left, and gives her right hand to the groom. The groom, taking her hand in his right puts it through his left arm—just her finger tips should rest near the bend of his elbow—and turns to face the chancel as he does so. It does not matter whether she takes his arm or whether they stand hand in hand at the foot of the chancel in front of the clergyman.

Her father has remained where she left him, on her left and a step or two behind her. The clergyman stands a step or two above them, and reads the betrothal. When he says "Who giveth this woman to be married?" the father goes forward, still on her left, and half way between her and the clergyman, but not in front of either, the bride turns slightly toward her father, and gives him her right hand, the father puts her hand into that of the clergyman and says at the same moment: "I do!" He then takes his place next to his wife at the end of the first pew on the left.

The Marriage Ceremony

A soloist or the choir then sings while the clergyman slowly ascends to the altar, before which the marriage is performed. The bride and groom follow slowly, the fingers of her right hand on his left arm.

The maid of honor, or else the first bridesmaid, moves out of line and follows on the left hand side until she stands immediately below the bride. The best man takes the same position exactly on the right behind the groom. At the termination of the anthem, the bride hands her bouquet to the maid of honor (or her prayer-book to the clergyman) and the bride and groom plight their troth.

When it is time for the ring, the best man produces it from his pocket. If in the handling from best man to groom, to clergyman, to groom again, and finally to the bride's finger, it should slip and fall, the best man must pick it up if he can without searching; if not, he quietly produces the duplicate which all careful best men carry in the other waistcoat pocket, and the ceremony proceeds. The lost ring—or the unused extra one—is returned to the jeweler's next day. Which ring, under the circumstances, the bride keeps, is a question as hard to answer as that of the Lady or the Tiger. Would she prefer the substitute ring that was actually the one she was married with? Or the one her husband bought and had marked for her? Or would she prefer not to have a substitute ring and have the whole wedding party on their knees searching? She alone can decide. Fortunately, even if the clergyman is very old and his hand shaky, a substitute is seldom necessary.

The wedding ring must not be put above the engagement ring. On her wedding day a bride either leaves her engagement ring at home when she goes to church or wears it on her right hand.

After The Ceremony

At the conclusion of the ceremony, the minister congratulates the new couple. The organ begins the recessional. The bride takes her bouquet from her maid of honor (who removes the veil if she wore one over her face). She then turns toward her husband—her bouquet in her right hand—and puts her left hand through his right arm, and they descend the steps.

The maid of honor, handing her own bouquet to a second bridesmaid, follows a short distance after the bride, at the same time stooping and straightening out the long train and veil. The bride and groom go on down the aisle. The best man disappears into the vestry room. At a perfectly conducted wedding he does not walk down the aisle with the maid of honor. The maid of honor recovers her bouquet and walks alone. If a bridesmaid performs the office of maid of honor, she takes her place among her companion bridesmaids who go next; and the ushers go last.

The best man has meanwhile collected the groom's belongings and dashed out of the side entrance and around to the front to give the groom his hat and stick. Sometimes the sexton takes charge of the groom's hat and stick and hands them to him at the church door as he goes out. But in either case the best man always hurries around to see the bride and groom into their carriage, which has been standing at the entrance to the awning since she and her father alighted from it.

All the other conveyances are drawn up in the reverse order from that in which they arrived. The bride's carriage leaves first, next come those of the bridesmaids, next the bride's mother and father, next the groom's mother and father, then the nearest members of both families, and finally all the other guests in the order of their being able to find their conveyances.

The best man goes back to the vestry, where he gives the fee to the clergyman, collects his own hat, and coat if he has one, and goes to the bride's house.

As soon as the recessional is over, the ushers hurry back and escort to the door all the ladies who were in the first pews, according to the order of precedence; the bride's mother first, then the groom's mother, then the other occupants of the first pew on either side, then the second and third pews, until all members of the immediate families have left the church. Meanwhile it is a breach of etiquette for other guests to leave their places. At some weddings, just before the bride's arrival, the ushers run ribbons down the whole length of the center aisle, fencing the congregation in. As soon as the occupants of the first pews have left, the ribbons are removed and all the other guests go out by themselves, the ushers having by that time hurried to the bride's house to make themselves useful at the reception.

At The House

An awning makes a covered way from the edge of the curb to the front door. At the lower end the chauffeur (or one of the caterer's men) stands to open the carriage door; and give return checks to the chauffeurs and their employers. Inside the house the florist has finished, an orchestra is playing in the hall or library, everything is in perfect order. The bride and groom have taken their places in front of the elaborate setting of flowering plants that has been arranged for them.

The bride stands on her husband's right and her bridesmaids are either grouped beyond her or else divided, half on her side and half on the side of the groom, forming a crescent with bride and groom in the center.