Mourning Wear For Men

The necessity of business and affairs which has made withdrawal into seclusion impossible, has also made it customary for the majority of men to go into mourning by the simple expedient of putting a black band on their hat or on the left sleeve of their usual clothes and wearing only white instead of colored linen.

A man never under any circumstances wears crepe. The band on his hat is of very fine cloth and varies in width according to the degree of mourning from two and a half inches to within half an inch of the top of a high hat. On other hats the width is fixed at about two and a half or three inches. The sleeve band, from three and a half to four and a half inches in width, is of dull broadcloth on overcoats or winter clothing, and of serge on summer clothes. The sleeve band of mourning is sensible for many reasons, the first being that of economy. Men's clothes do not come successfully from the encounter with dye vats, nor lend themselves to "alterations," and an entire new wardrobe is an unwarranted burden to most.

Except for the one black suit bought for the funeral and kept for Sunday church, or other special occasion, only wealthy men or widowers go to the very considerable expense of getting a new wardrobe. Widowers—especially if they are elderly—always go into black (which includes very dark gray mixtures) with a deep black band on the hat, and of course, black ties and socks and shoes and gloves.

Conventions Of Mourning For Men

Although the etiquette is less exacting, the standards of social observance are much the same for a man as for a woman. A widower should not be seen at any general entertainment, such as a dance, or in a box at the opera, for a year; a son for six months; a brother for three—at least! The length of time a father stays in mourning for a child is more a matter of his own inclination.

Mourning Livery

Coachmen and chauffeurs wear black liveries in town. In the country they wear gray or even their ordinary whipcord with a black band on the left sleeve.

The house footman is always put into a black livery with dull buttons and a black and white striped waistcoat. Maids are not put into mourning with the exception of a lady's maid or nurse who, through many years of service, has "become one of the family," and who personally desires to wear mourning as though for a relative of her own.

Acknowledgment Of Sympathy

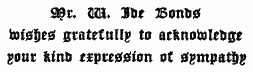

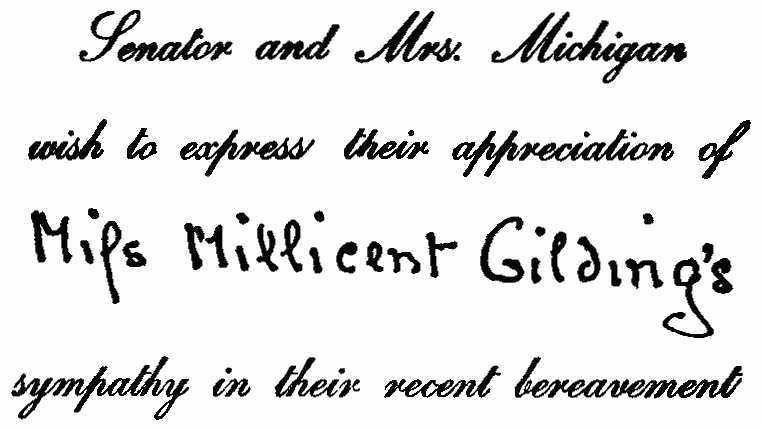

In the case of a very prominent person where messages of condolence, many of them impersonal, mount into the thousands, the sending of engraved cards to strangers is proper, such as:

or

Under no circumstances should such cards be sent to intimate friends, or to those who have sent flowers or written personal letters.

When some one with real sympathy in his heart has taken the trouble to select and send flowers, or has gone to the house and offered what service he might, or has in a spirit of genuine regard, written a personal letter, the receipt of words composed by a stationer and dispatched by a professional secretary is exactly as though his outstretched hand had been pushed aside.

A family in mourning is in retirement from all social activities. There is no excuse on the score of their "having no time." Also no one expects a long letter, nor does any one look for an early reply. A personal word on a visiting card is all any one asks for. The envelope may be addressed by some one else.

It takes but a moment to write "Thank you," or "Thank you for all sympathy," or "Thank you for your kind offers and sympathy." Or, on a sheet of letter paper:

"Thank you, dear Mrs. Smith, for your beautiful flowers and your kind sympathy."

Or:

"Your flowers were so beautiful! Thank you for them and for your loving message."

Or:

"Thank you for your sweet letter. I know you meant it and I appreciate it."

Many, many such notes can be written in a day. If the list is overlong, or the one who received the flowers and messages is in reality so prostrated that she (or he) is unable to perform the task of writing, then some member of her immediate family can write for her:

"Mother (or father) is too ill to write and asks me to thank you for your beautiful flowers and kind message."

Most people find a sad comfort as well as pain, in the reading and replying to letters and cards, but they should not sit at it too long; it is apt to increase rather than assuage their grief. Therefore, no one expects more than a word—but that word should be seemingly personal.

Obligations Of Presence At Funerals

Upon reading the death notice of a mere acquaintance you may leave your card at the house, if you feel so inclined, or you may merely send your card.

Upon the death of an intimate acquaintance or friend you should go at once to the house, write, "With sympathy" on your card and leave it at the door. Or you should write a letter to the family; in either case, you send flowers addressed to the nearest relative. On the card accompanying the flowers, you write, "With sympathy," "With deepest sympathy," or "With heartfelt sympathy," or "With love and sympathy." If there is a notice in the papers "requesting no flowers be sent," you send them only if you are a very intimate friend.

Or if you prefer, send a few flowers with a note, immediately after the funeral, to the member of the family who is particularly your friend.

If the notice says "funeral private" you do not go unless you have received a message from the family that you are expected, or unless you are such an intimate friend that you know you are expected without being asked. Where a general notice is published in the paper, it is proper and fitting that you should show sympathy by going to the funeral, even though you had little more than a visiting acquaintance with the family. You should not leave cards nor go to a funeral of a person with whom you have not in any way been associated or to whose house you have never been asked.

But it is heartless and delinquent if you do not go to the funeral of one with whom you were associated in business or other interests, or to whose house you were often invited, or where you are a friend of the immediate members of the family.

You should wear black clothes if you have them, or if not, the darkest, the least conspicuous you possess. Enter the church as quietly as possible, and as there are no ushers at a funeral, seat yourself where you approximately belong. Only a very intimate friend should take a position far up on the center aisle. If you are merely an acquaintance you should sit inconspicuously in the rear somewhere, unless the funeral is very small and the church big, in which case you may sit on the end seat of the center aisle toward the back.

CHAPTER XXV

THE COUNTRY HOUSE AND ITS HOSPITALITY

The difference between the great house with twenty to fifty guest rooms, all numbered like the rooms in a hotel, and the house of ordinary good size with from four to six guest rooms, or the farmhouse or small cottage which has but one "best" spare chamber, with perhaps a "man's room" on the ground floor, is much the same as the difference between the elaborate wedding and the simplest—one merely of degree and not of kind.

To be sure, in the great house, week-end guests often include those who are little more than acquaintances of the host and hostess, whereas the visitor occupying the only "spare" room is practically always an intimate friend. Excepting, therefore, that people who have few visitors never ask any one on their general list, and that those who fill an enormous house time and time again necessarily do, the etiquette, manners, guest room appointments and the people who occupy them, are precisely the same. Popular opinion to the contrary, a man's social position is by no means proportionate to the size of his house, and even though he lives in a bungalow, he may have every bit as high a position in the world of fashion as his rich neighbor in his palace—often much better!

We all of us know a Mr. Newgold who would give many of the treasures in his marble palace for a single invitation to Mrs. Oldname's comparatively little house, and half of all he possesses for the latter's knowledge, appearance, manner, instincts and position—none of which he himself is likely ever to acquire, though his children may! But in our description of great or medium or small houses, we are considering those only whose owners belong equally to best society and where, though luxuries vary from the greatest to the least, house appointments are in essentials alike.

This is a rather noteworthy fact: all people of good position talk alike, behave alike and live alike. Ill-mannered servants, incorrect liveries or service, sloppily dished food, carelessness in any of the details that to well-bred people constitute the decencies of living, are no more tolerated in the smallest cottage than in the palace. But since the biggest houses are those which naturally attract most attention, suppose we begin our detailed description with them.

House Party Of Many Guests

Perhaps there are ten or perhaps there are forty guests, but if there were only two or three, and the house a little instead of a big one, the details would be precisely the same.

A week-end means from Friday afternoon or from Saturday lunch to Monday morning. The usual time chosen for a house party is over a holiday, particularly where the holiday falls on a Friday or Monday, so that the men can take a Saturday off, and stay from Friday to Tuesday, or Thursday to Monday.

On whichever day the party begins, everyone arrives in the neighborhood of five o'clock, or a day later at lunch time. Many come in their own cars, the others are met at the station—sometimes by the host or a son, or, if it is to be a young party, by a daughter. The hostess herself rarely, if ever, goes to the station, not because of indifference or discourtesy but because other guests coming by motor might find the house empty.

It is very rude for a hostess to be out when her guests arrive. Even some one who comes so often as to be entirely at home, is apt to feel dispirited upon being shown into an empty house. Sometimes a guest's arrival unwelcomed can not be avoided; if, for instance, a man invited for tennis week or a football or baseball game, arrives before the game is over but too late to join the others at the sport.

When younger people come to visit the daughters, it is not necessary that their mother stay at home, since the daughters take their mother's place. Nor is it necessary that she receive the men friends of her son, unless the latter for some unavoidable reason, is absent.

No hostess must ever fail to send a car to the station or boat landing for every one who is expected. If she has not conveyances enough of her own, she must order public ones and have the fares charged to herself.

Greeting Of The Host

The host always goes out into the front hall and shakes hands with every one who arrives. He asks the guests if they want to be shown to their rooms, and, if not, sees that the gentlemen who come without valets give their keys to the butler or footman, and that the ladies without maids of their own give theirs to the maid who is on duty for the purpose.

Should any of them feel dusty or otherwise "untidy" they naturally ask if they may be shown to their rooms so that they can make themselves presentable. They should not, however, linger longer than necessary, as their hostess may become uneasy at their delay. Ladies do not—in fashionable houses—make their first appearance without a hat. Gentlemen, needless to say, leave theirs in the hall when they come in.

Travel in the present day, however, whether in parlor car or closed limousines, or even in open cars on macadam roads, obviates the necessity for an immediate removing of "travel stains," so that instead of seeking their rooms, the newcomers usually go directly into the library or out on the veranda or wherever the hostess is to be found behind the inevitable tea tray.

Greeting Of The Hostess

As soon as her guests appear in the doorway, the hostess at once rises, goes forward smiling, shakes hands and tells them how glad she is that they have safely come, or how glad she is to see them, and leads the way to the tea-table. This is one of the occasions when everyone is always introduced. Good manners also demand that the places nearest the hostess be vacated by those occupying them, and that the newly arrived receive attention from the hostess, who sees that they are supplied with tea, sandwiches, cakes and whatever the tea-table affords.

After tea, people either sit around and talk, or, more likely nowadays, they play bridge. About an hour before dinner the hostess asks how long every one needs to dress, and tells them the time. If any need a shorter time than she must allow for herself, she makes sure that they know the location of their rooms, and goes to dress.

A Room For Every Guest

It is almost unnecessary to say that in no well-appointed house is a guest, except under three circumstances, put in a room with any one else. The three exceptions are:

1. A man and wife, if the hostess is sure beyond a doubt that they occupy similar quarters when at home.

2. Two young girls who are friends and have volunteered, because the house is crowded, to room together in a room with two beds.

3. On an occasion such as a wedding, a ball, or an intercollegiate athletic event, young people don't mind for one night (that is spent for the greater part "up") how many are doubled; and house room is limited merely to cot space, sofas, and even the billiard table.

But she would be a very clumsy hostess, who, for a week-end, filled her house like a sardine box to the discomfort and resentment of every one.

In the well-appointed house, every guest room has a bath adjoining for itself alone, or shared with a connecting room and used only by a man and wife, two women or two men. A bathroom should never (if avoidable) be shared by a woman and a man. A suitable accommodation for a man and wife is a double room with bath and a single room next.

The perfect guest room is not necessarily a vast chamber decorated in an historically correct period. Its perfection is the result of nothing more difficult to attain than painstaking attention to detail, and its possession is within the reach of every woman who has the means to invite people to her house in the first place. The ideal guest room is never found except in the house of the ideal hostess, and it is by no means "idle talk" to suggest that every hostess be obliged to spend twenty-four hours every now and then in each room that is set apart for visitors. If she does not do this actually, she should do so in imagination. She should occasionally go into the guest bathroom and draw the water in every fixture, to see there is no stoppage and that the hot water faucets are not seemingly jokes of the plumber. If a man is to occupy the bathroom, she must see that the hook for a razor strop is not missing, and that there is a mirror by which he can see to shave both at night and by daylight. Even though she can see to powder her nose, it would be safer to make her husband bathe and shave both a morning and an evening in each bathroom and then listen carefully to what he says about it!

Even though she has a perfect housemaid, it is not unwise occasionally to make sure herself that every detail has been attended to; that in every bathroom there are plenty of bath towels, face towels, a freshly laundered wash rag, bath mat, a new cake of unscented bath soap in the bathtub soap rack, and a new cake of scented soap on the washstand.

It is not expected, but it is often very nice to find violet water, bath salts, listerine, talcum powder, almond or other hand or sunburn lotion, in decorated bottles on the washstand shelf; but to cover the dressing-table in the bedroom with brushes and an array of toilet articles is more of a nuisance than a comfort. A good clothes brush and whiskbroom are usually very acceptable, as strangely enough, guests almost invariably forget them.

A comforting adjunct to a bathroom that is given to a woman is a hot water bottle with a woolen cover, hanging on the back of the door. Even if the water does not run sufficiently hot, a guest seldom hesitates to ring for that, whereas no one ever likes to ask for a hot water bag—no matter how much she might long for it. A small bottle of Pyro is also convenient for one who brings a curling lamp.

"The ideal guest room is never found except in the house of the ideal hostess; and it is by no means idle talk to suggest that every hostess be obliged to spend twenty-four hours every now and then in each room set apart for visitors." [Page 414.]

In the bedroom the hostess should make sure (by sleeping in it at least once) that the bed is comfortable, that the sheets are long enough to tuck in, that there are enough pillows for one who sleeps with head high. There must also be plenty of covers. Besides the blankets there should be a wool-filled or an eiderdown quilt, in coloring to go with the room.

There should be a night light at the head of the bed. Not just a decorative glow-worm effect, but a light that is really good to lie in bed and read by. And always there should be books; chosen more to divert than to engross. The sort of selection appropriate for a guest room might best comprise two or three books of the moment, a light novel, a book of essays, another of short stories, and a few of the latest magazines. Spare-room books ought to be especially chosen for the expected guest. Even though one can not choose accurately for the taste of another, one can at least guess whether the visitor is likely to prefer transcendental philosophy or detective stories, and supply either accordingly.

There should be a candle and a box of matches—even though there is electric light it has been known to go out! And some people like to burn a candle all night. There must also be matches and ash receivers on the desk and a scrap-basket beside it.

In hot weather, every guest should have a palm leaf fan, and in August, even though there are screens, a fly killer.

In big houses with a swimming pool, bath-robes are supplied and often bathing suits. Otherwise dressing-gowns are not part of any guest room equipment.

A comfortable sofa is very important (if the room is big enough) with a sofa pillow or two, and with a lightweight quilt or afghan across the end of it.

The hostess should do her own hair in each room to see if the dressing-table is placed where there is a good light over it, both by electric and by daylight. A very simple expedient in a room where massive furniture and low windows make the daylight dressing-table difficult, is the European custom of putting an ordinary small table directly in the window and standing a good sized mirror on it. Nothing makes a more perfect arrangement for a woman.

And the pincushion! It is more than necessary to see that the pins are usable and not rust to the head. There should be black ones and white ones, long and short; also safety pins in several sizes. Three or four threaded needles of white thread, black, gray and tan silk are an addition that has proved many times welcome. She must also examine the writing desk to be sure that the ink is not a cracked patch of black dust at the bottom of the well, and the pens solid rust and the writing paper textures and sizes at odds with the envelopes. There should be a fresh blotter and a few stamps. Also thoughtful hostesses put a card in some convenient place, giving the post office schedule and saying where the mail bag can be found. And a calendar, and a clock that goes! is there anything more typical of the average spare room than the clock that is at a standstill?

There must be plenty of clothes hangers in the closets. For women a few hat stands, and for men trouser hangers and the coat hangers that have a bar across the shoulder piece.

It is unnecessary to add that every bureau drawer should be looked into to see that nothing belonging to the family is filling the space which should belong to the guest, and that the white paper lining the bottom is new. Curtains and sofa pillows must, of course, be freshly laundered; the furniture, floor, walls and ceiling unmarred and in perfect order.

When bells are being installed in new houses they should be on cords and hung at the side of the bed. Light switches should be placed at the side of the door going into the room and bathroom. It is scarcely practical to change the wiring in old houses; but it can at least be seen that the bells work.

People who like strong perfumes often mistakenly think they are giving pleasure in filling all the bedroom drawers with pads heavily scented. Instead of feeling pleasure, some people are made almost sick! But all people (hay-fever patients excepted) love flowers, and vases of them beautify rooms as nothing else can. Even a shabby little room, if dustlessly clean and filled with flowers, loses all effect of shabbiness and is "inviting" instead.

In a hunting country, there should be a bootjack and boothooks in the closet.

Guest rooms should have shutters and dark shades for those who like to keep the morning sun out. The rooms should also, if possible, be away from the kitchen end of the house and the nursery.

A shortcoming in many houses is the lack of a newspaper, and the thoughtful hostess who has the morning paper sent up with each breakfast tray, or has one put at each place on the breakfast table, deserves a halo.

At night a glass and a thermos pitcher of water should be placed by the bed. In a few very specially appointed houses, a small glass-covered tray of food is also put on the bed table, fruit or milk and sandwiches, or whatever is marked on the guest card.

The Guest Card

A clever device was invented by Mrs. Gilding whose palatially appointed house is run with the most painstaking attention to every one's comfort. On the dressing-table in each spare room at Golden Hall is a card pad with a pencil attached to it. But if the guest card is used, a specimen is given below.

Needless to say the cards are used only in huge houses that, because of their size, are necessarily run more like a clubhouse than as a "home."

In every house, the questions below are asked by the hostess, though the guests may not readily perceive the fact. At bedtime she always asks: "Would you like to come down to breakfast, or will you have it in your room?" If the guest says, in her room, she is then asked what she would like to eat. She is also asked whether she cares for milk or fruit or other light refreshment at bedtime, and if there is a special book she would like to take up to her room.

The guest card mentioned above is as follows:

Please Fill This Out Before Going Down To Dinner:

What time do you want to be awakened? .......................Or, will you ring? ..........................................

Will you breakfast up-stairs? ................................

Or down? ....................................................

Underscore Your Order:

Coffee, tea, chocolate, milk,Oatmeal, hominy, shredded wheat,

Eggs, how cooked?

Rolls, muffins, toast,

Orange, pear, grapes, melon.

At Bedtime Will You Take

Hot or cold milk, cocoa, orangeade,Sandwiches, meat, lettuce, jam,

Cake, crackers,

Oranges, apples, pears, grapes.

Besides this list, there is a catalogue of the library with a card, clipped to the cover, saying:

"Following books for room No. X." Then four or six blank lines and a place for the guest's signature.

At The Dinner Hour

Every one goes down to dinner as promptly as possible and the procedure is exactly that of all dinners. If it is a big party, the gentlemen offer their arms to the ladies the host or hostess has designated. At the end of the evening, it is the custom that the hostess suggest going up-stairs, rather than the guests who ordinarily depart after dinner. But etiquette is not very strictly followed in this, and a reasonable time after dinner, if any one is especially tired he or she quite frankly says: "I wonder if you would mind very much if I went to bed?" The hostess always answers: "Why, no, certainly not! I hope you will find everything in your room! If not, will you ring?"

It is not customary for the hostess to go up-stairs with a guest, so long as others remain in her drawing-room. If there is only one lady, or a young girl, the hostess accompanies her to her room, and asks if everything has been thought of for her comfort.

How Guests Are Asked And Received

Many older ladies adhere to former practise and always write personal notes of invitation. All others write or telegraph to people at a distance, and send telephone messages to those nearby.

When a house is to be filled with friends of daughters or sons of the house, the young people in the habit of coming to the house, or young men, whether making a first visit or not, do not need any invitation further than one given them verbally by a daughter, or even a son. But a married couple, or a young girl invited for the first time, should have the verbal invitation of daughter or son seconded by a note or at least a telephone message sent by the mother herself.

Every one is always asked for a specified time. Even a near relative comes definitely for a week, or a month, or whatever period is selected. This is because other plans have to be made by the owners of the house, such as inviting another group of guests, or preparing to go away themselves.

Who Are Asked On House Parties

Excepting when strangers bring influential letters of introduction, or when a relative or very intimate friend recently married is invited with her new husband or his bride, only very large and general house parties include any one who is not an intimate friend.

At least seventy per cent of American house parties are young people, either single or not long married, and, in any event, all those asked to any one party—unless the hostess is a failure (or a genius)—belong to the same social group. Perhaps a more broad-minded attitude prevails among young people in other parts of the country, but wilfully narrow-minded Miss Young New York is very chary of accepting an invitation until she finds out who among her particular friends are also invited. If Mrs. Stranger asks her for a week-end, no matter how much she may like Mrs. Stranger personally, she at once telephones two or three of her own group. If some of them are going, she "accepts with pleasure," but if not, the chances are she "regrets." If, on the other hand, she is asked by the Gildings, she accepts at once. Not merely because Golden Hall is the ultimate in luxury, but because Mrs. Gilding has a gift for entertaining, including her selection of people, amounting to genius. On the other hand, Miss Young New York would accept with equal alacrity the invitation of the Jack Littlehouses, where there is no luxury at all. Here in fact, a guest is quite as likely as not to be pressed into service as auxiliary nurse, gardener or chauffeur. But the personality of the host and hostess is such that there is scarcely a day in the week when the motors of the most popular of the younger set are not parked at the Littlehouse door.

People We Love To Stay With

We enjoy staying with certain people usually for one of two reasons. First, because they have wonderful, luxurious houses, filled with amusing people; and visiting them is a period crammed with continuous and delightful experience, even though such a visit has little that suggests any personal intercourse or friendship with one's hostess. The other reason we love to visit a certain house is, on the contrary, entirely personal to the host or hostess. We love the house because we love its owner. Nowhere do we feel so much at home, and though it may have none of the imposing magnificence of the great house, it is often far more charming.

Five flunkeys can not do more towards a guest's comfort than to take his hat and stick and to show him the way to the drawing-room. A very smart young New Yorker who is also something of a wag, says that when going to a very magnificent house, he always tries to wear sufficient articles so that he shall have one to bestow upon each footman. Some one saw him, upon entering a palace that is a counterpart of the Worldlys,' quite solemnly hand his hat to the first footman, his stick to the second, his coat to the third, his muffler to the fourth, his gloves to the fifth, and his name to the sixth, as he entered the drawing-room. Needless to say he did this as a matter of pure amusement to himself. Of course six men servants, or more, do add to the impressiveness of a house that is a palace and are a fitting part of the picture. And yet a neat maid servant at the door can divest a guest of his hat and coat, and lead the way to the sitting-room, with equal facility.

Having several times mentioned Golden Hall, the palatial country house of the Gildings, suppose we join the guests and see what the last word in luxury and lavish hospitality is.

Golden Hall is not an imaginary place, except in name. It exists within a hundred miles of New York. The house is a palace, the grounds are a park. There is not only a long wing of magnificent guest rooms in the house, occupied by young girls or important older people, but there is also a guest annex, a separate building designed and run like the most luxurious country club. The second floor has nothing but bedrooms, with bath for each. The third floor has bachelor rooms, and rooms for visiting valets. Visiting maids are put in a separate third floor wing. On the ground floor there is a small breakfast room; a large living-room filled with books, magazines, a billiard and pool table; beyond the living-room is a fully equipped gymnasium; and beyond that a huge, white marble, glass-walled natatorium. The swimming pool is fifty feet by one hundred; on three sides is just a narrow shelf-like walkway, but the fourth is wide and is furnished as a room with lounging chairs upholstered in white oilcloth. Opening out of this are perfectly equipped Turkish and Russian baths in charge of the best Swedish masseur and masseuse procurable.

In the same building are two squash courts, a racquet court, a court tennis court, and a bowling alley. But the feature of the guest building is a glass-roofed and enclosed riding ring—not big enough for games of polo, but big enough for practise in winter,—built along one entire side of it.

The stables are full of polo ponies and hunters, the garage full of cars, the boathouse has every sort of boat—sailboats, naphtha launches, a motor boat and even a shell. Every amusement is open-heartedly offered, in fact, especially devised for the guests.

At the main house there is a ballroom with a stage at one end. An orchestra plays every night. New moving pictures are shown and vaudeville talent is imported from New York. This is the extreme of luxury in entertaining. As Mrs. Toplofty said at the end of a bewilderingly lavish party: "How are any of us ever going to amuse any one after this? I feel like doing my guest rooms up in moth balls."

No one, however, has discovered that invitations to Mrs. Toplofty's are any less welcome. Besides, excitement-loving youth and exercise-devotees were never favored guests at the Hudson Manor anyway.

The Small House Of Perfection

It matters not in the slightest whether the guest room's carpet is Aubusson or rag, whether the furniture is antique, or modern, so long as it is pleasing of its kind. On the other hand, because a house is little is no reason that it can not be as perfect in every detail—perhaps more so—as the palace of the multiest millionaire!

The attributes of the perfect house can not be better represented than by Brook Meadows Farm, the all-the-year home of the Oldnames. Nor can anything better illustrate its perfection than an incident that actually took place there.

A great friend of the Oldnames, but not a man who went at all into society, or considered whether people had position or not, was invited with his new wife—a woman from another State and of much wealth and discernment—to stay over a week-end at Brook Meadows. Never having met the Oldnames, she asked something about their house and life in order to decide what type of clothes to pack.

"Oh, it's just a little farmhouse. Oldname wears a dinner coat, of course; his wife wears—I don't know what—but I have never seen her dressed up a bit!"

"Evidently plain people," thought his wife. And aloud: "I wonder what evening dress I have that is high enough. I can put in the black lace day dress; perhaps I had better put in my cerise satin——"

"The cerise?" asked her husband, "Is that the red you had on the other night? It is much too handsome, much! I tell you, Mrs. Oldname never wears a dress that you could notice. She always looks like a lady, but she isn't a dressy sort of person at all."

So the bride packed her plainest (that is her cheapest) clothes, but at the last, she put in the "cerise."

When she and her husband arrived at the railroad station, that at least was primitive enough, and Mr. Oldname in much worn tweeds might have come from a castle or a cabin; country clothes are no evidence. But her practised eye noticed the perfect cut of the chauffeur's coat and that the car, though of an inexpensive make, was one of the prettiest on the market, and beautifully appointed.

"At least they have good taste in motors and accessories," thought she, and was glad she had brought her best evening dress.

They drove up to a low white shingled house, at the end of an old-fashioned brick walk bordered with flowers. The visitor noticed that the flowers were all of one color, all in perfect bloom. She knew no inexperienced gardener produced that apparently simple approach to a door that has been chosen as frontispiece in more than one book on Colonial architecture. The door was opened by a maid in a silver gray taffeta dress, with organdie collar, cuffs and apron, white stockings and silver buckles on black slippers, and the guest saw a quaint hall and vista of rooms that at first sight might easily be thought "simple" by an inexpert appraiser; but Mrs. Oldname, who came forward to greet her guests, was the antithesis of everything the bride's husband had led her to believe.

To describe Mrs. Oldname as simple is about as apt as to call a pearl "simple" because it doesn't dazzle; nor was there an article in the apparently simple living-room that would be refused were it offered to a museum.

The tea-table was Chinese Chippendale and set with old Spode on a lacquered tray over a mosaic-embroidered linen tea-cloth. The soda biscuits and cakes were light as froth, the tea an especial blend imported by a prominent connoisseur and given every Christmas to his friends. There were three other guests besides the bride and groom: a United States Senator, and a diplomat and his wife who were on their way from a post in Europe to one in South America. Instead of "bridge" there was conversation on international topics until it was time to dress for dinner.

When the bride went to her room (which adjoined that of her husband) she found her bath drawn, her clothes laid out, and the dressing-table lights lighted.

That night the bride wore her cerise dress to one of the smartest dinners she ever went down to, and when they went up-stairs and she at last saw her husband alone, she took him to task. "Why in the name of goodness didn't you tell me the truth about these people?"

"Oh," said he abashed, "I told you it was a little house—it was you who insisted on bringing that red dress. I told you it was too handsome!"

"Handsome!" she cried in tears, "I don't own anything half good enough to compare with the least article in this house. That `simple' little woman as you call her would, I think, almost make a queen seem provincial! And as for her clothes, they are priceless—just as everything is in this little gem of a house. Why, the window curtains are as fine as the best clothes in my trousseau."

The two houses contrasted above are two extremes, but each a luxury. The Oldnames' expenditure, though in no way comparable with the Worldlys' or the Gildings,' is far beyond any purse that can be called moderate.

The really moderate purse inevitably precludes a woman from playing an important rôle as hostess, for not even the greatest magnetism and charm can make up to spoiled guests for lack of essential comfort. The only exceptions are a bungalow at the seashore or a camp in the woods, where a confirmed luxury-lover is desperately uncomfortable for the first twenty-four hours, but invariably gets used to the lack of comfort almost as soon as he gets dependent upon it; and plunging into a lake for bath, or washing in a little tin basin, sleeping on pine boughs without any sheets at all, eating tinned foods and flapjacks on tin plates with tin utensils, he seems to lack nothing when the air is like champagne and the company first choice.

Guest Room Service

If a visitor brings no maid of her own, the personal maid of the hostess (if she has one—otherwise the housemaid) always unpacks the bags or trunks, lays toilet articles out on the dressing-table and in the bathroom, puts folded things in the drawers and hangs dresses on hangers in the closet. If when she unpacks she sees that something of importance has been forgotten, she tells her mistress, or, in the case of a servant who has been long employed, she knows what selection to make herself, and supplies the guest without asking with such articles as comb and brush or clothes brush, or bathing suit and bath-robe.

The valet of the host performs the same service for men. In small establishments where there is no lady's maid or valet, the housemaid is always taught to unpack guests' belongings and to press and hook up ladies' dresses, and gentlemen's clothes are sent to a tailor to be pressed after each wearing.

In big houses, breakfast trays for women guests are usually carried to the bedroom floor by the butler (some butlers delegate this service to a footman) and are handed to the lady's maid who takes the tray into the room. In small houses they are carried up by the waitress.

Trays for men visitors are rare, but when ordered are carried up and into the room by the valet, or butler. If there are no men servants the waitress has to carry up the tray.

When a guest rings for breakfast, the housemaid or the valet goes into the room, opens the blinds, and in cold weather lights the fire, if there is an open one in the room. Asking whether a hot, cool or cold bath is preferred, he goes into the bathroom, spreads a bath mat on the floor, a big bath towel over a chair, with the help of a thermometer draws the bath, and sometimes lays out the visitor's clothes. As few people care for more than one bath a day and many people prefer their bath before dinner instead of before breakfast, this office is often performed at dinner dressing time instead of in the morning.

Tips

The "tip-roll" in a big house seems to us rather appalling, but compared with the amounts given in a big English house, ours are mere pittances. Pleasant to think that something is less expensive in our country than in Europe!

Fortunately in this country, when you dine in a friend's house you do not "tip" the butler, nor do you tip a footman or parlor-maid who takes your card to the mistress of the house, nor when you leave a country house do you have to give more than five dollars to any one whatsoever. A lady for a week-end stay gives two or three dollars to the lady's maid, if she went without her own, and one or two dollars to every one who waited on her. Intimate friends in a small house send tips to all the servants—perhaps only a dollar apiece, but no one is forgotten. In a very big house this is never done and only those are tipped who have served you. If you had your maid with you, you always give her a tip (about two dollars) to give the cook (often the second one) who prepared her meals and one dollar for the kitchen maid who set her table.

A gentleman scarcely ever "remembers" any of the women servants (to their chagrin) except a waitress, and tips only the butler and the valet, and sometimes the chauffeur. The least he can offer any of the men-servants is two dollars and the most ever is five. No woman gets as much as that, for such short service.

In a few houses the tipping system is abolished, and in every guest room, in a conspicuous place on the dressing-table or over the bath tub where you are sure to read it, is a sign, saying:

"Please do not offer tips to my servants. Their contract is with this special understanding, and proper arrangements have been made to meet it; you will not only create 'a situation,' but cause the immediate dismissal of any one who may be persuaded by you to break this rule of the house."

The notice is signed by the host. The "arrangement" referred to is one whereby every guest means a bonus added to their wages of so much per person per day for all employees. This system is much preferred by servants for two reasons. First, self-respecting ones dislike the demeaning effect of a tip (an occasional few won't take them). Secondly, they can absolutely count that so many visitors will bring them precisely such an amount.