CHAPTER XXXIV

THE CLOTHES OF A GENTLEMAN

It would seem that some of our great clothing establishments, with an eye to our polyglot ancestry, have attempted to incorporate some feature of every European national costume into a "harmonious" whole, and have thus given us that abiding horror, the freak American suit. You will see it everywhere, on Broadway of every city and Main Street of every town, on the boardwalks and beaches of coast resorts, and even in remote farming villages. It comes up to hit you in the face year after year in all its amazing variations: waist-line under the arm pits, "trick" little belts, what-nots in the cuffs; trousers so narrow you fear they will burst before your eyes, pockets placed in every position, buttons clustered together in a tight little row or reduced to one. And the worst of it is, few of our younger men know any better until they go abroad and find their wardrobe a subject for jest and derision.

If you would dress like a gentleman, you must do one of two things; either study the subject of a gentleman's wardrobe until you are competent to pick out good suits from freaks and direct your misguided tailor, or, at least until your perceptions are trained, go to an English one. This latter method is the easiest, and, by all odds, the safest. It is not Anglomania but plain common sense to admit that, just as the Rue de la Paix in Paris is the fountainhead of fashions for women, Bond Street in London is the home of irreproachable clothes for men.

And yet, curiously enough, just as a woman shopping in Paris can buy frightful clothes—or the most beautiful; a man can in America buy the worst clothes in the world—and the best.

The ordinary run of English clothes may not be especially good, but they are, on the other hand, never bad; whereas American freak clothes are distortions like the reflections seen in the convex and concave mirrors of the amusement parks. But not even the leading tailors of Bond Street can excel the supremely good American tailor—whose clothes however are identical in every particular with those of London, and their right to be called "best" is for greater perfection of workmanship and fit. This last is a dangerous phrase; "fit" means perfect set and line, not plaster tightness.

However, let us suppose that you are either young, or at least fairly young; that you have unquestioned social position, and that you are going to get yourself an entire wardrobe. Let us also suppose your money is not unlimited, so that it may also be seen where you may not, or may if necessary, economize.

Formal Evening Clothes

Your full dress is the last thing to economize on. It must be perfect in fit, cut and material, and this means a first-rate tailor. It must be made of a dull-faced worsted, either black or night blue, on no account of broadcloth. Aside from satin facing and collar, which can have lapels or be cut shawl-shaped, and wide braid on the trousers, it must have no trimming whatever. Avoid satin or velvet cuffs, moiré neck ribbons and fancy coat buttons as you would the plague.

Wear a plain white linen waistcoat, not one of cream colored silk, or figured or even black brocade. Have all your linen faultlessly clean—always—and your tie of plain white lawn, tied so it will not only stay in place but look as though nothing short of a backward somersault could disarrange it.

Your handkerchief must be white; gloves (at opera or ball) white; flower in buttonhole (if any) white. If you are a normal size, you can in America buy inexpensive shirts, and white waistcoats that are above reproach, but if you are abnormally tall or otherwise an "out size" so that everything has to be "made to order," you will have to pay anywhere from double to four times as much for each article you put on.

When you go out on the street, wear an English silk hat, not one of the taper crowned variety popular in the "movies." And wear it on your head, not on the back of your neck. Have your overcoat of plain black or dark blue material, for you must wear an overcoat with full dress even in summer. Use a plain white or black and white muffler. Colored ones are impossible. Wear white buckskin gloves if you can afford them; otherwise gray or khaki doeskin, and leave them in your overcoat pocket. Your stick should be of plain Malacca or other wood, with either a crooked or straight handle. The only ornamentation allowable is a plain silver or gold band, or top; but perfectly plain is best form.

And lastly, wear patent leather pumps, shoes or ties, and plain black silk socks, and leave your rubbers—if you must wear them, in the coat room.

The Tuxedo

The Tuxedo, which is the essential evening dress of a gentleman, is simply the English dinner coat. It was first introduced in this country at the Tuxedo Club to provide something less formal than the swallow-tail, and the name has clung ever since. To a man who can not afford to get two suits of evening clothes, the Tuxedo is of greater importance. It is worn every evening and nearly everywhere, whereas the tail coat is necessary only at balls, formal dinners, and in a box at the opera. Tuxedo clothes are made of the same materials and differ from full dress ones in only three particulars: the cut of the coat, the braid on the trousers, and the use of a black tie instead of a white one. The dinner coat has no tails and is cut like a sack suit except that it is held closed in front by one button at the waist line. (A full dress coat, naturally, hangs open.) The lapels are satin faced, and the collar left in cloth, or if it is shawl-shaped the whole collar is of satin.

The trousers are identical with full dress ones except that braid, if used at all, should be narrow. "Cuffed" trousers are not good form, nor should a dinner coat be double-breasted.

Fancy ties are bad form. Choose a plain black silk or satin one. Wear a white waistcoat if you can afford the strain on your laundry bill, otherwise a plain black one. By no means wear a gray one nor a gray tie.

The smartest hat for town wear is an opera, but a straw or felt which is proper in the country, is not out of place in town. Otherwise, in the street the accessories are the same as those already given under the previous heading.

The House Suit

The house suit is an extravagance that may be avoided, and an "old" Tuxedo suit worn instead.

A gentleman is always supposed to change his clothes for dinner, whether he is going out or dining at home alone or with his family, and for this latter occasion some inspired person evolved the house, or lounge, suit, which is simply a dinner coat and trousers cut somewhat looser than ordinary evening ones, made of an all-silk or silk and wool fabric in some dark color, and lined with either satin or silk. Nothing more comfortable—or luxurious—could be devised for sitting in a deep easy-chair after dinner, in a reclining position that is ruinous to best evening clothes.

Its purpose is really to save wear on evening clothes, and to avoid some of their discomfort also, because they can not be given hard or careless usage and long survive. A house suit is distinctly what the name implies, and is not an appropriate garment to wear out for dinner or to receive any but intimate guests in at home. The accessories are a pleated shirt, with turndown stiff collar, and black bow tie, or even an unstarched shirt with collar attached (white of course). The coat is made with two buttons instead of one, because no waistcoat is worn with it.

Formal afternoon dress consists of a black cutaway coat with white piqué or black cloth waistcoat, and gray-and-black striped trousers. The coat may be bound with braid, or, even in better taste, plain. A satin-faced lapel is not conservative on a cutaway, but it is the correct facing for the more formal (and elderly) frock coat. Either a cutaway or a frock coat is always accompanied by a silk hat, and best worn with plain black waistcoat and a black bow tie or a black and white four-in-hand tie. A gray silk ascot worn with the frock coat is supposed to be the correct wedding garment of the bride's father. (For details of clothes worn by groom and ushers at a wedding, see chapter on weddings.)

Shoes may be patent leather, although black calfskin are at present the fashion, either with or without spats. If with spats, be sure that they fit close; nothing is worse than a wrinkled spat or one that sticks out over the instep like the opened bill of a duck!

Though gray cutaway suits and gray top hats have always been worn to the races in England, they do not seem suitable here, as races in America are not such full-dress occasions as in France and England. But at a spring wedding or other formal occasions a sand-colored double-breasted linen waistcoat with spats and bow tie to match looks very well with a black cutaway and almost black trousers, on a man who is young.

The Business Suit

The business suit or three-piece sack is made or marred by its cut alone. It is supposed to be an every-day inconspicuous garment and should be. A few rules to follow are:

Don't choose striking patterns of materials; suitable woolen stuffs come in endless variety, and any which look plain at a short distance are "safe," though they may show a mixture of colors or pattern when viewed closely.

Don't get too light a blue, too bright a green, or anything suggesting a horse blanket. At the present moment trousers are made with a cuff; sleeves are not. Lapels are moderately small. Padded shoulders are an abomination. Peg-topped trousers equally bad. If you must be eccentric, save your efforts for the next fancy dress ball, where you may wear what you please, but in your business clothing be reasonable.

Above everything, don't wear white socks, and don't cover yourself with chains, fobs, scarf pins, lodge emblems, etc., and don't wear "horsey" shirts and neckties. You will only make a bad impression on every one you meet. The clothes of a gentleman are always conservative; and it is safe to avoid everything than can possibly come under the heading of "novelty."

Jewelry

In your jewelry let diamonds be conspicuous by their absence. Nothing is more vulgar than a display of "ice" on a man's shirt front, or on his fingers.

There is a good deal of jewelry that a gentleman may be allowed to wear, but it must be chosen with discrimination. Pearl shirt-studs (real ones) are correct for full dress only, and not to be worn with a dinner coat unless they are so small as to be entirely inconspicuous. Otherwise you may wear enamel studs (that look like white linen) or black onyx with a rim of platinum, or with a very inconspicuous pattern in diamond chips, but so tiny that they can not be told from a threadlike design in platinum—or others equally moderate.

Waistcoat buttons, studs and cuff links, worn in sets, is an American custom that is permissible. Both waistcoat buttons and cuff links may be jewelled and valuable, but they must not have big precious stones or be conspicuous.

A watch chain should be very thin and a man's ring is usually a seal ring of plain gold or a dark stone. If a man wears a jewel at all it should be sunk into a plain "gypsy hoop" setting that has no ornamentation, and worn on his "little," not his third, finger.

Gay-colored socks and ties are quite appropriate with flannels or golf tweeds. Only in your riding clothes you must again be conservative. If you can get boots built on English lines, wear them; otherwise wear leggings. And remember that all leather must be real leather in the first place and polished until its surface is like glass.

Have your breeches fit you. The coat is less important, in fact, any odd coat will do. Your legs are the cynosure of attention in riding.

Most men in the country wear knickerbockers with golf stockings, with a sack or a belted or a semi-belted coat, and in any variety of homespuns or tweeds or rough worsted materials. Or they wear long trousered flannels. Coats are of the polo or ulster variety. For golf or tennis many men wear sweater coats. Shirts are of cheviot or silk or flannel, all with soft collars attached and to match.

The main thing is to dress appropriately. If you are going to play golf, wear golf clothes; if tennis, wear flannels. Do not wear a yachting cap ashore unless you are living on board a yacht.

White woolen socks are correct with white buckskin shoes in the country, but not in town.

If some semi-formal occasion comes up, such as a country tea, the time-worn conservative blue coat with white flannel trousers is perennially good.

Other Hints

The well-dressed man is always a paradox. He must look as though he gave his clothes no thought and as though literally they grew on him like a dog's fur, and yet he must be perfectly groomed. He must be close-shaved and have his hair cut and his nails in good order (not too polished). His linen must always be immaculate, his clothes "in press," his shoes perfectly "done." His brown shoes must shine like old mahogany, and his white buckskin must be whitened and polished like a prize bull terrier at a bench show. Ties and socks and handkerchief may go together, but too perfect a match betrays an effort for "effect" which is always bad.

The well-dressed man never wears the same suit or the same pair of shoes two days running. He may have only two suits, but he wears them alternately; if he has four suits he should wear each every fourth day. The longer time they have "to recover" their shape, the better.

What To Wear On Various Occasions

The appropriate clothes for various occasions are given below. If ever in doubt what to wear, the best rule is to err on the side of informality. Thus, if you are not sure whether to put on your dress suit or your Tuxedo, wear the latter.

Full Dress

- At the opera.

- At an evening wedding.

- At a dinner to which the invitations are worded in the third person.

- At a ball, or formal evening entertainment.

- At certain State functions on the Continent of Europe in broad daylight.

Tuxedo

- At the theater.

- At most dinners.

- At informal parties.

- Dining at home.

- Dining in a restaurant.

A Cutaway Or Frock Coat With Striped Trousers

- At a noon or afternoon wedding.

- On Sunday for church (in the city).

- At any formal daytime function.

- In England to business.

- As usher at a wedding.

- As pall-bearer.

- All informal daytime occasions.

- Traveling.

- The coat of a blue suit with white flannel or duck trousers for a lunch, or to church, in the country.

- A blue or black sack suit will do in place of a cutaway at a wedding, but not if you are the groom or an usher.

Country Clothes

- Only in the country.

To wear odd tweed coats and flannel trousers in town is not only inappropriate, but bad taste.

CHAPTER XXXV

THE KINDERGARTEN OF ETIQUETTE

In the houses of the well-to-do where the nursery is in charge of a woman of refinement who is competent to teach little children proper behavior, they are never allowed to come to table in the dining-room until they have learned at least the elements of good manners. But whether in a big house of this description, or in a small house where perhaps the mother alone must be the teacher, children can scarcely be too young to be taught the rudiments of etiquette, nor can the teaching be too patiently or too conscientiously carried out.

Training a child is exactly like training a puppy; a little heedless inattention and it is out if hand immediately; the great thing is not to let it acquire bad habits that must afterward be broken. Any child can be taught to be beautifully behaved with no effort greater than quiet patience and perseverance, whereas to break bad habits once they are acquired is a Herculean task.

Elementary Table Manners

Since a very little child can not hold a spoon properly, and as neatness is the first requisite in table-manners, it should be allowed to hold its spoon as it might take hold of a bar in front of it, back of the hand up, thumb closed over fist. The pusher (a small flat piece of silver at right angles to a handle) is held in the same way, in the left hand. Also in the first eating lessons, a baby must be allowed to put a spoon in its mouth, pointed end foremost. Its first lessons must be to take small mouthfuls, to eat very slowly, to spill nothing, to keep the mouth shut while chewing and not smear its face over. In drinking, a child should use both hands to hold a mug or glass until its hand is big enough so it can easily hold a glass in one. When it can eat without spilling anything or smearing its lips, and drink without making grease "moons" on its mug or tumbler (by always wiping its mouth before drinking), it may be allowed to come to table in the dining-room as a treat, for Sunday lunch or breakfast. Or if it has been taught by its mother at table, she can relax her attention somewhat from its progress. Girls are usually daintier and more easily taught than boys, but most children will behave badly at table if left to their own devices. Even though they may commit no serious offenses, such as making a mess of their food or themselves, or talking with their mouths full, all children love to crumb bread, flop this way and that in their chairs, knock spoons and forks together, dawdle over their food, feed animals—if any are allowed in the room—or become restless and noisy.

Once graduated to the dining-room, any reversion to such tactics must be firmly reprehended, and the child should understand that continued offense means a return to the nursery. But before company it is best to say as little as possible, since too much nagging in the presence of strangers lessens a child's incentive to good behavior before them. If it refuses to behave nicely, much the best thing to do is to say nothing, but get up and quietly lead it from the table back to the nursery. It is not only bad for the child but annoying to a guest to continue instructions before "company," and the child learns much more quickly to be well-behaved if it understands that good behavior is the price of admission to grown-up society. A word or two such as, "Don't lean on the table, darling," or "pay attention to what you are doing, dear," should suffice. But a child that is noisy, that reaches out to help itself to candy or cake, that interrupts the conversation, that eats untidily has been allowed to leave the nursery before it has been properly graduated.

Table manners must, of course, proceed slowly in exactly the same way that any other lessons proceed in school. Having learned when a baby to use the nursery implements of spoon and pusher, the child, when it is a little older, discards them for the fork, spoon and knife.

As soon, therefore, as his hand is dexterous enough, the child must be taught to hold his fork, no longer gripped baby-fashion in his fist, but much as a pencil is held in writing; only the fingers are placed nearer the "top" than the "point," the thumb and two first fingers are closed around the handle two-thirds of the way up the shank, and the food is taken up shovel-wise on the turned-up prongs. At first his little fingers will hold his fork stiffly, but as he grows older his fingers will become more flexible just as they will in holding his pencil. If he finds it hard work to shovel his food, he can, for a while, continue to use his nursery pusher. By and by the pusher is changed for a small piece of bread, which is held in his left hand and between thumb and first two fingers, and against which the fork shovels up such elusive articles as corn, peas, poached egg, etc.

The Spoon

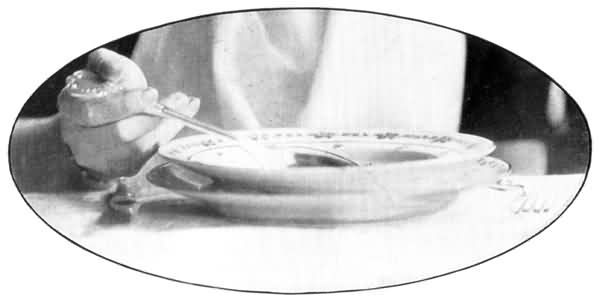

In using the spoon, he holds it in his right hand like the fork. In eating cereal or dessert, he may be allowed to dip the bowl of the spoon toward him and eat from the end, but in eating soup he must dip his spoon away from him—turning the outer rim of the bowl down as he does so—fill the bowl not more than three-quarters full and sip it, without noise, out of the side (not the end) of the bowl. The reason why the bowl must not be filled full is because it is impossible to lift a brimming spoonful of liquid to his mouth without spilling some, or in the case of porridge without filling his mouth too full. While still very young he may be taught never to leave the spoon in a cup while drinking out of it, but after stirring the cocoa, or whatever it is, to lay the spoon in the saucer.

A very ugly table habit, which seems to be an impulse among all children, is to pile a great quantity of food on a fork and then lick or bite it off piecemeal. This must on no account be permitted. It is perfectly correct, however, to sip a little at a time, of hot liquid from a spoon. In taking any liquid either from a spoon or drinking vessel, no noise must ever be made.

"In Eating Soup The Child Must Dip His Spoon Away From Him—turning The Outer Rim Of The Spoon Down As He Does So...." [Page 573.]

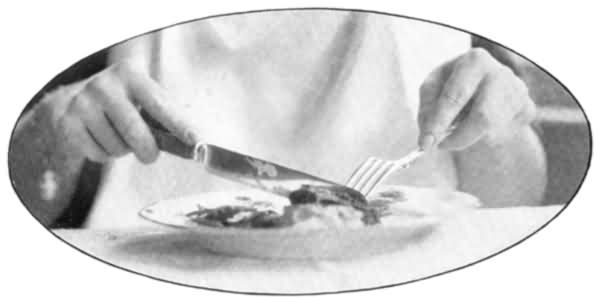

"In Being Taught To Use Knife And Fork Together, The Child Should At First Cut Only Something Very Easy, Such As A Slice Of Chicken...." [Page 574.]

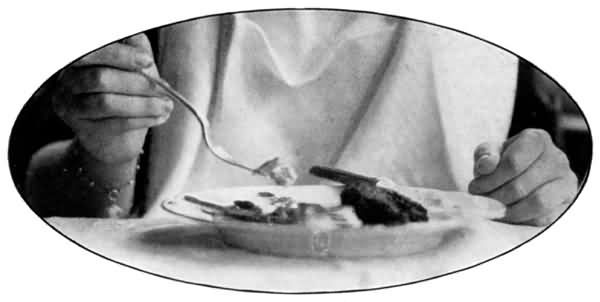

"Having Cut Off A Mouthful, He Thrusts The Fork Through It, With Prongs Pointed Downward And Conveys It To His Mouth With His Left Hand. He Must Learn To Cut Off And Eat One Mouthful At A Time." [Page 574.]

"When No Knife Is Being Used, The Fork Is Held In The Right Hand, Whether Used 'Prongs Down' To Impale The Meat, Or 'Prongs Up' To Lift Vegetables." [Page 575.]

"Bread Should Always Be Broken Into Small Pieces With The Fingers Before Being Buttered." [Page 583.]

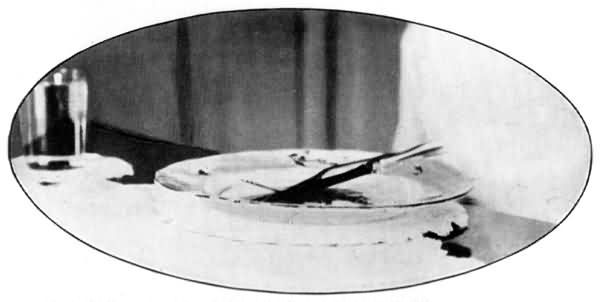

"When He Has Finished Eating, The Child Should Lay His Knife And Fork Close Together, Side By Side, With Handles Toward The Right Side Of His Plate...." [Page 575.]

In being taught to use his knife, the child should at first cut only something very easy, such as a slice of chicken; he should not attempt anything with bones or gristle, or anything that is tough. In his left hand is put his fork with the prongs downward, held near the top of the handle. His index finger is placed on the shank so that it points to the prongs, and is supported at the side by his thumb. His other fingers close underneath and hold the handle tight. He must never be allowed to hold his fork emigrant fashion, perpendicularly clutched in the clenched fist, and to saw across the food at its base with his knife.

The Knife

The knife is held in his right hand exactly as the fork is held in his left, firmly and at the end of the handle, with the index finger pointing down the back of the blade. In cutting he should learn not to scrape the back of the fork prongs with the cutting edge of the knife. Having cut off a mouthful, he thrusts the fork through it, with prongs pointed downward and conveys it to his mouth with his left hand. He must learn to cut off and eat one mouthful at a time.

It is unnecessary to add that the knife must never be put in his mouth; nor is it good form to use the knife unnecessarily. Soft foods, like croquettes, hash on toast, all eggs and vegetables, should be cut or merely broken apart with the edge of the fork held like the knife, after which the fork is turned in the hand to first (or shovel) position. The knife must never be used to scoop baked potato out of the skin, or to butter potato. A fork must be used for all manipulations of vegetables; butter for baked potatoes taken on the tip of the fork shovel fashion, laid on the potato, and then pressed down and mixed with the prongs held points curved up.

When no knife is being used, the fork is held in the right hand, whether used "prongs down" to impale the meat or "prongs up" to lift vegetables.

To pile mashed potato and other vegetables on the convex side of the fork on top of the meat for two or more inches of its length, is a disgusting habit dear to school boys, and one that is more easily prevented than corrected. In fact, taking a big mouthful (next to smearing his face and chewing with mouth open) is the worst offense at table.

When he has finished eating, he should lay his knife and fork close together, side by side, with handles toward the right side of his plate, the handles projecting an inch or two beyond the rim of the plate. They must be placed far enough on the plate so that there is no danger of their over-balancing on to the table or floor when removed at the end of the course.

Other Table Matters

The distance from the table at which it is best to sit, is a matter of personal comfort. A child should not be allowed to be so close that his elbows are bent like a grasshopper's, nor so far back that food is apt to be spilled in transit from plate to mouth. Children like to drink very long and rapidly, all in one breath, until they are pink around the eyes, and are literally gasping. They also love to put their whole hands in their finger-bowls and wiggle their fingers.

A baby of two, or at least by the time he is three, should be taught to dip the tips of his fingers in the finger-bowl, without playing, draw the fingers of the right hand across his mouth, and then wipe his lips and fingers on the apron of his bib.

No small child can be expected to use a napkin instead of a bib. No matter how nicely behaved he may be, there is always danger of his spilling something, some time. Soft boiled egg is hideously difficult to eat without ever getting a drop of it down the front, and it is much easier to supply him with a clean bib for the next meal than to change his dress for the next moment.

Very little children usually have "hot water plates" that are specially made like a double plate with hot water space between, on which the meat is cut up and the vegetables "fixed" in the pantry, and brought to the children before other people at the table are served. Not only because it is hard for them to be made to wait, and have their attention attracted by food not for them, but because they take so long to eat. As soon as they are old enough to eat everything on the table, they are served, not last, but in the regular rotation at table in which they come.

Table Tricks That Must Be Corrected

To sit up straight and keep their hands in their laps when not occupied with eating, is very hard for a child, but should be insisted upon in order to prevent a careless attitude that all too readily degenerates into flopping this way and that, and into fingering whatever is in reach. He must not be allowed to warm his hands on his plate, or drum on the table, or screw his napkin into a rope or make marks on the tablecloth. If he shows talent as an artist, give him pencils or modeling wax in his playroom, but do not let him bite his slice of bread into the silhouette of an animal, or model figures in soft bread at the table. And do not allow him to construct a tent out of two forks, or an automobile chassis out of tumblers and knives. Food and table implements are not playthings, nor is the dining-room a playground.

Talking At Table

When older people are present at table and a child wants to say something, he must be taught to stop eating momentarily and look at his mother, who at the first pause in the conversation will say, "What is it, dear?" And the child then has his say. If he wants merely to launch forth on a long subject of his own conversation, his mother says, "Not now, darling, we will talk about that by and by," or "Don't you see that mother is talking to Aunt Mary?"

When children are at table alone with their mother, they should not only be allowed to talk but unconsciously trained in table conversation as well as in table manners. Children are all more or less little monkeys in that they imitate everything they see. If their mother treats them exactly as she does her visitors they in turn play "visitor" to perfection. Nothing hurts the feelings of children more than not being allowed to behave like grown persons when they think they are able. To be helped, to be fed, to have their food cut up, all have a stultifying effect upon their development as soon as they have become expert enough to attempt these services for themselves.

Children should be taught from the time they are little not to talk about what they like and don't like. A child who is not allowed to say anything but "No, thank you," at home, will not mortify his mother in public by screaming, "I hate steak, I won't eat potato, I want ice cream!"

Quietness At Table

Older children should not be allowed to jerk out their chairs, to flop down sideways, to flick their napkins by one corner, to reach out for something, or begin to eat nuts, fruit or other table decorations. A child as well as a grown person should sit down quietly in the center of his chair and draw it up to the table (if there is no one to push it in for him) by holding the seat in either hand while momentarily lifting himself on his feet. He must not "jump" or "rock" his chair into place at the table. In getting up from the table, again he must push his chair back quietly, using his hands on either side of the chair seat, and not by holding on to the table edge and giving himself, chair and all, a sudden shove! There should never be a sound made by the pushing in or out of chairs at table.

The bad manners of American children, which unfortunately are supposed by foreigners to be typical, are nearly always the result of their being given "star" parts by over-fond but equally over-foolish mothers. It is only necessary to bring to mind the most irritating and objectionable child one knows, and the chances are that its mother continually throws the spotlight on it by talking to it, and about it, and by calling attention to its looks or its cunning ways or even, possibly, its naughtiness.

It is humanly natural to make a fuss over little children, particularly if they are pretty, and it takes quite super-human control for a young mother not to "show off" her treasure, but to say instead, "Please do not pay any attention to her." Some children, who are especially free from self-consciousness, stand "stardom" better than others who are more readily spoiled; but in nine cases out of ten, the old-fashioned method that assigned children to inconspicuous places in the background and decreed they might be seen but not heard, produced men and women of far greater charm than the modern method of encouraging public self-expression from infancy upward.

Chief Virtue: Obedience

No young human being, any more than a young dog, has the least claim to attractiveness unless it is trained to manners and obedience. The child that whines, interrupts, fusses, fidgets, and does nothing that it is told to do, has not the least power of attraction for any one, even though it may have the features of an angel and be dressed like a picture. Another that may have no claim to beauty whatever, but that is sweet and nicely behaved, exerts charm over every one.

When possible, a child should be taken away the instant it becomes disobedient. It soon learns that it can not "stay with mother" unless it is well-behaved. This means that it learns self-control in babyhood. Not only must children obey, but they must never be allowed to "show off" or become pert, or to contradict or to answer back; and after having been told "no," they must never be allowed by persistent nagging to win "yes."

A child that loses its temper, that teases, that is petulant and disobedient, and a nuisance to everybody, is merely a victim, poor little thing, of parents who have been too incompetent or negligent to train it to obedience. Moreover, that same child when grown will be the first to resent and blame the mother's mistaken "spoiling" and lack of good sense.

Fair Play

Nothing appeals to children more than justice, and they should be taught in the nursery to "play fair" in games, to respect each other's property and rights, to give credit to others, and not to take too much credit to themselves. Every child must be taught never to draw attention to the meagre possessions of another child whose parents are not as well off as her own. A purse-proud, overbearing child who says to a playmate, "My clothes were all made in Paris, and my doll is ever so much handsomer than yours," or "Is that real lace on your collar?" is not impressing her young friend with her grandeur and discrimination but with her disagreeableness and rudeness. A boy who brags about what he has, and boasts of what he can do, is only less objectionable because other boys are sure to "take it out of him" promptly and thoroughly! Nor should a bright, observing child be encouraged to pick out other people's failings, or to tell her mother how inferior other children are compared with herself. If she wins a race or a medal or is praised, she naturally tells her mother, and her mother naturally rejoices with her, and it is proper that she should; but a wise mother directs her child's mental attitude to appreciate the fact that arrogance, selfishness and conceit can win no place worth having in the world.

Children At Afternoon Tea

A custom in many fashionable houses is to allow children as soon as they are old enough, to come into the drawing-room or library at tea-time, as nothing gives them a better opportunity to learn how to behave in company. Little boys are always taught to bow to visitors; little girls to curtsy. Small boys are taught to place the individual tables, hand plates and tea, and pass sandwiches and cakes. If there are no boys, girls perform this office; very often they both do. When everybody has been helped, the children are perhaps allowed a piece of cake, which they put on a tea-plate, and sit down, and eat nicely. But as the tea-hour is very near their supper time, they are often allowed nothing, and after making themselves useful, go out of the room again. If many people are present and the children are not spoken to, they leave the room unobtrusively and quietly. If only one or two are present, especially those whom the children know well, they shake hands, and say "Good-by," and walk (not run) out of the room.

This is one of the ways in which well-bred people become used from childhood to instinctive good manners. Unless they are spoken to, they would not think of speaking or making themselves noticed in any way. Very little children who have not reached the age of "discretion," which may be placed at about five, possibly not until six, usually go in the drawing-room at tea-time only when near relatives or intimate friends of the family are there. Needless to say that they are always washed and dressed. Some children wear special afternoon clothes, but usually the clean clothes put on at tea-time go on again the next morning, except the thin socks and house slippers which are reserved for the "evening hour" of their day.

Children's Parties

A small girl (or boy) giving a party should receive with her mother at the door and greet all her friends as they come in. If it is her birthday and other children bring her gifts, she must say "Thank you" politely. On no account must she be allowed to tell a child "I hate dolls," if a friend has brought her one. She must learn at an early age that as hostess she must think of her guests rather than herself, and not want the best toys in the grab-bag or scream because another child gets the prize that is offered in a contest. If beaten in a game, a little girl, no less than her brothers, must never cry, or complain that the contest is "not fair" when she loses. She must try to help her guests have a good time, and not insist on playing the game she likes instead of those which the other children suggest.

When she herself goes to a party, she must say, "How do you do," when she enters the room, and curtsy to the lady who receives. A boy makes a bow. They should have equally good manners as when at home, and not try to grab more than their share of favors or toys. When it is time to go home, they must say, "Good-by, I had a very good time," or, "Good-by, thank you ever so much."

The Child's Reply

If the hostess says, "Good-by, give my love to your mother!" the child answers, "Yes, Mrs. Smith." In all monosyllabic replies a child must not say "Yes" or "No" or "What?" A boy in answering a gentleman still uses the old-fashioned "Yes, sir," "No, sir," "I think so, sir," but ma'am has gone out of style. Both boys and girls must therefore answer, "No, Mrs. Smith," "Yes, Miss Jones." A girl says "Yes, Mr. Smith," rather than "sir." All children should say, "What did you say, mother?" "No, father," "Thank you, Aunt Kate," "Yes, Uncle Fred," etc.

They need not insert a name in a long sentence nor with "please," or "thank you." "Yes, please," or "No, thank you," is quite sufficient. Or in answering, "I just saw Mary down in the garden," it is not necessary to add "Mrs. Smith" at the end.