‘Is there nothing,’ he thought, glancing at her as she sat at the head of the table, where her youthful figure, small and slight, but very graceful, looked as pretty as it looked misplaced; ‘is there nothing that will move that face?’

Yes! By Jupiter, there was something, and here it was, in an unexpected shape. Tom appeared. She changed as the door opened, and broke into a beaming smile.

A beautiful smile. Mr. James Harthouse might not have thought so much of it, but that he had wondered so long at her impassive face. She put out her hand—a pretty little soft hand; and her fingers closed upon her brother’s, as if she would have carried them to her lips.

‘Ay, ay?’ thought the visitor. ‘This whelp is the only creature she cares for. So, so!’

The whelp was presented, and took his chair. The appellation was not flattering, but not unmerited.

‘When I was your age, young Tom,’ said Bounderby, ‘I was punctual, or I got no dinner!’

‘When you were my age,’ resumed Tom, ‘you hadn’t a wrong balance to get right, and hadn’t to dress afterwards.’

‘Never mind that now,’ said Bounderby.

‘Well, then,’ grumbled Tom. ‘Don’t begin with me.’

‘Mrs. Bounderby,’ said Harthouse, perfectly hearing this under-strain as it went on; ‘your brother’s face is quite familiar to me. Can I have seen him abroad? Or at some public school, perhaps?’

‘No,’ she resumed, quite interested, ‘he has never been abroad yet, and was educated here, at home. Tom, love, I am telling Mr. Harthouse that he never saw you abroad.’

‘No such luck, sir,’ said Tom.

There was little enough in him to brighten her face, for he was a sullen young fellow, and ungracious in his manner even to her. So much the greater must have been the solitude of her heart, and her need of some one on whom to bestow it. ‘So much the more is this whelp the only creature she has ever cared for,’ thought Mr. James Harthouse, turning it over and over. ‘So much the more. So much the more.’

Both in his sister’s presence, and after she had left the room, the whelp took no pains to hide his contempt for Mr. Bounderby, whenever he could indulge it without the observation of that independent man, by making wry faces, or shutting one eye. Without responding to these telegraphic communications, Mr. Harthouse encouraged him much in the course of the evening, and showed an unusual liking for him. At last, when he rose to return to his hotel, and was a little doubtful whether he knew the way by night, the whelp immediately proffered his services as guide, and turned out with him to escort him thither.

CHAPTER III

THE WHELP

It was very remarkable that a young gentleman who had been brought up under one continuous system of unnatural restraint, should be a hypocrite; but it was certainly the case with Tom. It was very strange that a young gentleman who had never been left to his own guidance for five consecutive minutes, should be incapable at last of governing himself; but so it was with Tom. It was altogether unaccountable that a young gentleman whose imagination had been strangled in his cradle, should be still inconvenienced by its ghost in the form of grovelling sensualities; but such a monster, beyond all doubt, was Tom.

‘Do you smoke?’ asked Mr. James Harthouse, when they came to the hotel.

‘I believe you!’ said Tom.

He could do no less than ask Tom up; and Tom could do no less than go up. What with a cooling drink adapted to the weather, but not so weak as cool; and what with a rarer tobacco than was to be bought in those parts; Tom was soon in a highly free and easy state at his end of the sofa, and more than ever disposed to admire his new friend at the other end.

Tom blew his smoke aside, after he had been smoking a little while, and took an observation of his friend. ‘He don’t seem to care about his dress,’ thought Tom, ‘and yet how capitally he does it. What an easy swell he is!’

Mr. James Harthouse, happening to catch Tom’s eye, remarked that he drank nothing, and filled his glass with his own negligent hand.

‘Thank’ee,’ said Tom. ‘Thank’ee. Well, Mr. Harthouse, I hope you have had about a dose of old Bounderby to-night.’ Tom said this with one eye shut up again, and looking over his glass knowingly, at his entertainer.

‘A very good fellow indeed!’ returned Mr. James Harthouse.

‘You think so, don’t you?’ said Tom. And shut up his eye again.

Mr. James Harthouse smiled; and rising from his end of the sofa, and lounging with his back against the chimney-piece, so that he stood before the empty fire-grate as he smoked, in front of Tom and looking down at him, observed:

‘What a comical brother-in-law you are!’

‘What a comical brother-in-law old Bounderby is, I think you mean,’ said Tom.

‘You are a piece of caustic, Tom,’ retorted Mr. James Harthouse.

There was something so very agreeable in being so intimate with such a waistcoat; in being called Tom, in such an intimate way, by such a voice; in being on such off-hand terms so soon, with such a pair of whiskers; that Tom was uncommonly pleased with himself.

‘Oh! I don’t care for old Bounderby,’ said he, ‘if you mean that. I have always called old Bounderby by the same name when I have talked about him, and I have always thought of him in the same way. I am not going to begin to be polite now, about old Bounderby. It would be rather late in the day.’

‘Don’t mind me,’ returned James; ‘but take care when his wife is by, you know.’

‘His wife?’ said Tom. ‘My sister Loo? O yes!’ And he laughed, and took a little more of the cooling drink.

James Harthouse continued to lounge in the same place and attitude, smoking his cigar in his own easy way, and looking pleasantly at the whelp, as if he knew himself to be a kind of agreeable demon who had only to hover over him, and he must give up his whole soul if required. It certainly did seem that the whelp yielded to this influence. He looked at his companion sneakingly, he looked at him admiringly, he looked at him boldly, and put up one leg on the sofa.

‘My sister Loo?’ said Tom. ‘She never cared for old Bounderby.’

‘That’s the past tense, Tom,’ returned Mr. James Harthouse, striking the ash from his cigar with his little finger. ‘We are in the present tense, now.’

‘Verb neuter, not to care. Indicative mood, present tense. First person singular, I do not care; second person singular, thou dost not care; third person singular, she does not care,’ returned Tom.

‘Good! Very quaint!’ said his friend. ‘Though you don’t mean it.’

‘But I do mean it,’ cried Tom. ‘Upon my honour! Why, you won’t tell me, Mr. Harthouse, that you really suppose my sister Loo does care for old Bounderby.’

‘My dear fellow,’ returned the other, ‘what am I bound to suppose, when I find two married people living in harmony and happiness?’

Tom had by this time got both his legs on the sofa. If his second leg had not been already there when he was called a dear fellow, he would have put it up at that great stage of the conversation. Feeling it necessary to do something then, he stretched himself out at greater length, and, reclining with the back of his head on the end of the sofa, and smoking with an infinite assumption of negligence, turned his common face, and not too sober eyes, towards the face looking down upon him so carelessly yet so potently.

‘You know our governor, Mr. Harthouse,’ said Tom, ‘and therefore, you needn’t be surprised that Loo married old Bounderby. She never had a lover, and the governor proposed old Bounderby, and she took him.’

‘Very dutiful in your interesting sister,’ said Mr. James Harthouse.

‘Yes, but she wouldn’t have been as dutiful, and it would not have come off as easily,’ returned the whelp, ‘if it hadn’t been for me.’

The tempter merely lifted his eyebrows; but the whelp was obliged to go on.

‘I persuaded her,’ he said, with an edifying air of superiority. ‘I was stuck into old Bounderby’s bank (where I never wanted to be), and I knew I should get into scrapes there, if she put old Bounderby’s pipe out; so I told her my wishes, and she came into them. She would do anything for me. It was very game of her, wasn’t it?’

‘It was charming, Tom!’

‘Not that it was altogether so important to her as it was to me,’ continued Tom coolly, ‘because my liberty and comfort, and perhaps my getting on, depended on it; and she had no other lover, and staying at home was like staying in jail—especially when I was gone. It wasn’t as if she gave up another lover for old Bounderby; but still it was a good thing in her.’

‘Perfectly delightful. And she gets on so placidly.’

‘Oh,’ returned Tom, with contemptuous patronage, ‘she’s a regular girl. A girl can get on anywhere. She has settled down to the life, and she don’t mind. It does just as well as another. Besides, though Loo is a girl, she’s not a common sort of girl. She can shut herself up within herself, and think—as I have often known her sit and watch the fire—for an hour at a stretch.’

‘Ay, ay? Has resources of her own,’ said Harthouse, smoking quietly.

‘Not so much of that as you may suppose,’ returned Tom; ‘for our governor had her crammed with all sorts of dry bones and sawdust. It’s his system.’

‘Formed his daughter on his own model?’ suggested Harthouse.

‘His daughter? Ah! and everybody else. Why, he formed Me that way!’ said Tom.

‘Impossible!’

‘He did, though,’ said Tom, shaking his head. ‘I mean to say, Mr. Harthouse, that when I first left home and went to old Bounderby’s, I was as flat as a warming-pan, and knew no more about life, than any oyster does.’

‘Come, Tom! I can hardly believe that. A joke’s a joke.’

‘Upon my soul!’ said the whelp. ‘I am serious; I am indeed!’ He smoked with great gravity and dignity for a little while, and then added, in a highly complacent tone, ‘Oh! I have picked up a little since. I don’t deny that. But I have done it myself; no thanks to the governor.’

‘And your intelligent sister?’

‘My intelligent sister is about where she was. She used to complain to me that she had nothing to fall back upon, that girls usually fall back upon; and I don’t see how she is to have got over that since. But she don’t mind,’ he sagaciously added, puffing at his cigar again. ‘Girls can always get on, somehow.’

‘Calling at the Bank yesterday evening, for Mr. Bounderby’s address, I found an ancient lady there, who seems to entertain great admiration for your sister,’ observed Mr. James Harthouse, throwing away the last small remnant of the cigar he had now smoked out.

‘Mother Sparsit!’ said Tom. ‘What! you have seen her already, have you?’

His friend nodded. Tom took his cigar out of his mouth, to shut up his eye (which had grown rather unmanageable) with the greater expression, and to tap his nose several times with his finger.

‘Mother Sparsit’s feeling for Loo is more than admiration, I should think,’ said Tom. ‘Say affection and devotion. Mother Sparsit never set her cap at Bounderby when he was a bachelor. Oh no!’

These were the last words spoken by the whelp, before a giddy drowsiness came upon him, followed by complete oblivion. He was roused from the latter state by an uneasy dream of being stirred up with a boot, and also of a voice saying: ‘Come, it’s late. Be off!’

‘Well!’ he said, scrambling from the sofa. ‘I must take my leave of you though. I say. Yours is very good tobacco. But it’s too mild.’

‘Yes, it’s too mild,’ returned his entertainer.

‘It’s—it’s ridiculously mild,’ said Tom. ‘Where’s the door! Good night!’

He had another odd dream of being taken by a waiter through a mist, which, after giving him some trouble and difficulty, resolved itself into the main street, in which he stood alone. He then walked home pretty easily, though not yet free from an impression of the presence and influence of his new friend—as if he were lounging somewhere in the air, in the same negligent attitude, regarding him with the same look.

The whelp went home, and went to bed. If he had had any sense of what he had done that night, and had been less of a whelp and more of a brother, he might have turned short on the road, might have gone down to the ill-smelling river that was dyed black, might have gone to bed in it for good and all, and have curtained his head for ever with its filthy waters.

CHAPTER IV

MEN AND BROTHERS

‘Oh, my friends, the down-trodden operatives of Coketown! Oh, my friends and fellow-countrymen, the slaves of an iron-handed and a grinding despotism! Oh, my friends and fellow-sufferers, and fellow-workmen, and fellow-men! I tell you that the hour is come, when we must rally round one another as One united power, and crumble into dust the oppressors that too long have battened upon the plunder of our families, upon the sweat of our brows, upon the labour of our hands, upon the strength of our sinews, upon the God-created glorious rights of Humanity, and upon the holy and eternal privileges of Brotherhood!’

‘Good!’ ‘Hear, hear, hear!’ ‘Hurrah!’ and other cries, arose in many voices from various parts of the densely crowded and suffocatingly close Hall, in which the orator, perched on a stage, delivered himself of this and what other froth and fume he had in him. He had declaimed himself into a violent heat, and was as hoarse as he was hot. By dint of roaring at the top of his voice under a flaring gaslight, clenching his fists, knitting his brows, setting his teeth, and pounding with his arms, he had taken so much out of himself by this time, that he was brought to a stop, and called for a glass of water.

As he stood there, trying to quench his fiery face with his drink of water, the comparison between the orator and the crowd of attentive faces turned towards him, was extremely to his disadvantage. Judging him by Nature’s evidence, he was above the mass in very little but the stage on which he stood. In many great respects he was essentially below them. He was not so honest, he was not so manly, he was not so good-humoured; he substituted cunning for their simplicity, and passion for their safe solid sense. An ill-made, high-shouldered man, with lowering brows, and his features crushed into an habitually sour expression, he contrasted most unfavourably, even in his mongrel dress, with the great body of his hearers in their plain working clothes. Strange as it always is to consider any assembly in the act of submissively resigning itself to the dreariness of some complacent person, lord or commoner, whom three-fourths of it could, by no human means, raise out of the slough of inanity to their own intellectual level, it was particularly strange, and it was even particularly affecting, to see this crowd of earnest faces, whose honesty in the main no competent observer free from bias could doubt, so agitated by such a leader.

Good! Hear, hear! Hurrah! The eagerness both of attention and intention, exhibited in all the countenances, made them a most impressive sight. There was no carelessness, no languor, no idle curiosity; none of the many shades of indifference to be seen in all other assemblies, visible for one moment there. That every man felt his condition to be, somehow or other, worse than it might be; that every man considered it incumbent on him to join the rest, towards the making of it better; that every man felt his only hope to be in his allying himself to the comrades by whom he was surrounded; and that in this belief, right or wrong (unhappily wrong then), the whole of that crowd were gravely, deeply, faithfully in earnest; must have been as plain to any one who chose to see what was there, as the bare beams of the roof and the whitened brick walls. Nor could any such spectator fail to know in his own breast, that these men, through their very delusions, showed great qualities, susceptible of being turned to the happiest and best account; and that to pretend (on the strength of sweeping axioms, howsoever cut and dried) that they went astray wholly without cause, and of their own irrational wills, was to pretend that there could be smoke without fire, death without birth, harvest without seed, anything or everything produced from nothing.

The orator having refreshed himself, wiped his corrugated forehead from left to right several times with his handkerchief folded into a pad, and concentrated all his revived forces, in a sneer of great disdain and bitterness.

‘But oh, my friends and brothers! Oh, men and Englishmen, the down-trodden operatives of Coketown! What shall we say of that man—that working-man, that I should find it necessary so to libel the glorious name—who, being practically and well acquainted with the grievances and wrongs of you, the injured pith and marrow of this land, and having heard you, with a noble and majestic unanimity that will make Tyrants tremble, resolve for to subscribe to the funds of the United Aggregate Tribunal, and to abide by the injunctions issued by that body for your benefit, whatever they may be—what, I ask you, will you say of that working-man, since such I must acknowledge him to be, who, at such a time, deserts his post, and sells his flag; who, at such a time, turns a traitor and a craven and a recreant, who, at such a time, is not ashamed to make to you the dastardly and humiliating avowal that he will hold himself aloof, and will not be one of those associated in the gallant stand for Freedom and for Right?’

The assembly was divided at this point. There were some groans and hisses, but the general sense of honour was much too strong for the condemnation of a man unheard. ‘Be sure you’re right, Slackbridge!’ ‘Put him up!’ ‘Let’s hear him!’ Such things were said on many sides. Finally, one strong voice called out, ‘Is the man heer? If the man’s heer, Slackbridge, let’s hear the man himseln, ’stead o’ yo.’ Which was received with a round of applause.

Slackbridge, the orator, looked about him with a withering smile; and, holding out his right hand at arm’s length (as the manner of all Slackbridges is), to still the thundering sea, waited until there was a profound silence.

‘Oh, my friends and fellow-men!’ said Slackbridge then, shaking his head with violent scorn, ‘I do not wonder that you, the prostrate sons of labour, are incredulous of the existence of such a man. But he who sold his birthright for a mess of pottage existed, and Judas Iscariot existed, and Castlereagh existed, and this man exists!’

Here, a brief press and confusion near the stage, ended in the man himself standing at the orator’s side before the concourse. He was pale and a little moved in the face—his lips especially showed it; but he stood quiet, with his left hand at his chin, waiting to be heard. There was a chairman to regulate the proceedings, and this functionary now took the case into his own hands.

‘My friends,’ said he, ‘by virtue o’ my office as your president, I askes o’ our friend Slackbridge, who may be a little over hetter in this business, to take his seat, whiles this man Stephen Blackpool is heern. You all know this man Stephen Blackpool. You know him awlung o’ his misfort’ns, and his good name.’

With that, the chairman shook him frankly by the hand, and sat down again. Slackbridge likewise sat down, wiping his hot forehead—always from left to right, and never the reverse way.

‘My friends,’ Stephen began, in the midst of a dead calm; ‘I ha’ hed what’s been spok’n o’ me, and ’tis lickly that I shan’t mend it. But I’d liefer you’d hearn the truth concernin myseln, fro my lips than fro onny other man’s, though I never cud’n speak afore so monny, wi’out bein moydert and muddled.’

Slackbridge shook his head as if he would shake it off, in his bitterness.

‘I’m th’ one single Hand in Bounderby’s mill, o’ a’ the men theer, as don’t coom in wi’ th’ proposed reg’lations. I canna coom in wi’ ’em. My friends, I doubt their doin’ yo onny good. Licker they’ll do yo hurt.’

Slackbridge laughed, folded his arms, and frowned sarcastically.

‘But ’t an’t sommuch for that as I stands out. If that were aw, I’d coom in wi’ th’ rest. But I ha’ my reasons—mine, yo see—for being hindered; not on’y now, but awlus—awlus—life long!’

Slackbridge jumped up and stood beside him, gnashing and tearing. ‘Oh, my friends, what but this did I tell you? Oh, my fellow-countrymen, what warning but this did I give you? And how shows this recreant conduct in a man on whom unequal laws are known to have fallen heavy? Oh, you Englishmen, I ask you how does this subornation show in one of yourselves, who is thus consenting to his own undoing and to yours, and to your children’s and your children’s children’s?’

There was some applause, and some crying of Shame upon the man; but the greater part of the audience were quiet. They looked at Stephen’s worn face, rendered more pathetic by the homely emotions it evinced; and, in the kindness of their nature, they were more sorry than indignant.

‘’Tis this Delegate’s trade for t’ speak,’ said Stephen, ‘an’ he’s paid for ’t, an’ he knows his work. Let him keep to ’t. Let him give no heed to what I ha had’n to bear. That’s not for him. That’s not for nobbody but me.’

There was a propriety, not to say a dignity in these words, that made the hearers yet more quiet and attentive. The same strong voice called out, ‘Slackbridge, let the man be heern, and howd thee tongue!’ Then the place was wonderfully still.

‘My brothers,’ said Stephen, whose low voice was distinctly heard, ‘and my fellow-workmen—for that yo are to me, though not, as I knows on, to this delegate here—I ha but a word to sen, and I could sen nommore if I was to speak till Strike o’ day. I know weel, aw what’s afore me. I know weel that yo aw resolve to ha nommore ado wi’ a man who is not wi’ yo in this matther. I know weel that if I was a lyin parisht i’ th’ road, yo’d feel it right to pass me by, as a forrenner and stranger. What I ha getn, I mun mak th’ best on.’

‘Stephen Blackpool,’ said the chairman, rising, ‘think on ’t agen. Think on ’t once agen, lad, afore thou’rt shunned by aw owd friends.’

There was an universal murmur to the same effect, though no man articulated a word. Every eye was fixed on Stephen’s face. To repent of his determination, would be to take a load from all their minds. He looked around him, and knew that it was so. Not a grain of anger with them was in his heart; he knew them, far below their surface weaknesses and misconceptions, as no one but their fellow-labourer could.

‘I ha thowt on ’t, above a bit, sir. I simply canna coom in. I mun go th’ way as lays afore me. I mun tak my leave o’ aw heer.’

He made a sort of reverence to them by holding up his arms, and stood for the moment in that attitude; not speaking until they slowly dropped at his sides.

‘Monny’s the pleasant word as soom heer has spok’n wi’ me; monny’s the face I see heer, as I first seen when I were yoong and lighter heart’n than now. I ha’ never had no fratch afore, sin ever I were born, wi’ any o’ my like; Gonnows I ha’ none now that’s o’ my makin’. Yo’ll ca’ me traitor and that—yo I mean t’ say,’ addressing Slackbridge, ‘but ’tis easier to ca’ than mak’ out. So let be.’

He had moved away a pace or two to come down from the platform, when he remembered something he had not said, and returned again.

‘Haply,’ he said, turning his furrowed face slowly about, that he might as it were individually address the whole audience, those both near and distant; ‘haply, when this question has been tak’n up and discoosed, there’ll be a threat to turn out if I’m let to work among yo. I hope I shall die ere ever such a time cooms, and I shall work solitary among yo unless it cooms—truly, I mun do ’t, my friends; not to brave yo, but to live. I ha nobbut work to live by; and wheerever can I go, I who ha worked sin I were no heighth at aw, in Coketown heer? I mak’ no complaints o’ bein turned to the wa’, o’ bein outcasten and overlooken fro this time forrard, but hope I shall be let to work. If there is any right for me at aw, my friends, I think ’tis that.’

Not a word was spoken. Not a sound was audible in the building, but the slight rustle of men moving a little apart, all along the centre of the room, to open a means of passing out, to the man with whom they had all bound themselves to renounce companionship. Looking at no one, and going his way with a lowly steadiness upon him that asserted nothing and sought nothing, Old Stephen, with all his troubles on his head, left the scene.

Then Slackbridge, who had kept his oratorical arm extended during the going out, as if he were repressing with infinite solicitude and by a wonderful moral power the vehement passions of the multitude, applied himself to raising their spirits. Had not the Roman Brutus, oh, my British countrymen, condemned his son to death; and had not the Spartan mothers, oh my soon to be victorious friends, driven their flying children on the points of their enemies’ swords? Then was it not the sacred duty of the men of Coketown, with forefathers before them, an admiring world in company with them, and a posterity to come after them, to hurl out traitors from the tents they had pitched in a sacred and a God-like cause? The winds of heaven answered Yes; and bore Yes, east, west, north, and south. And consequently three cheers for the United Aggregate Tribunal!

Slackbridge acted as fugleman, and gave the time. The multitude of doubtful faces (a little conscience-stricken) brightened at the sound, and took it up. Private feeling must yield to the common cause. Hurrah! The roof yet vibrated with the cheering, when the assembly dispersed.

Thus easily did Stephen Blackpool fall into the loneliest of lives, the life of solitude among a familiar crowd. The stranger in the land who looks into ten thousand faces for some answering look and never finds it, is in cheering society as compared with him who passes ten averted faces daily, that were once the countenances of friends. Such experience was to be Stephen’s now, in every waking moment of his life; at his work, on his way to it and from it, at his door, at his window, everywhere. By general consent, they even avoided that side of the street on which he habitually walked; and left it, of all the working men, to him only.

He had been for many years, a quiet silent man, associating but little with other men, and used to companionship with his own thoughts. He had never known before the strength of the want in his heart for the frequent recognition of a nod, a look, a word; or the immense amount of relief that had been poured into it by drops through such small means. It was even harder than he could have believed possible, to separate in his own conscience his abandonment by all his fellows from a baseless sense of shame and disgrace.

The first four days of his endurance were days so long and heavy, that he began to be appalled by the prospect before him. Not only did he see no Rachael all the time, but he avoided every chance of seeing her; for, although he knew that the prohibition did not yet formally extend to the women working in the factories, he found that some of them with whom he was acquainted were changed to him, and he feared to try others, and dreaded that Rachael might be even singled out from the rest if she were seen in his company. So, he had been quite alone during the four days, and had spoken to no one, when, as he was leaving his work at night, a young man of a very light complexion accosted him in the street.

‘Your name’s Blackpool, ain’t it?’ said the young man.

Stephen coloured to find himself with his hat in his hand, in his gratitude for being spoken to, or in the suddenness of it, or both. He made a feint of adjusting the lining, and said, ‘Yes.’

‘You are the Hand they have sent to Coventry, I mean?’ said Bitzer, the very light young man in question.

Stephen answered ‘Yes,’ again.

‘I supposed so, from their all appearing to keep away from you. Mr. Bounderby wants to speak to you. You know his house, don’t you?’

Stephen said ‘Yes,’ again.

‘Then go straight up there, will you?’ said Bitzer. ‘You’re expected, and have only to tell the servant it’s you. I belong to the Bank; so, if you go straight up without me (I was sent to fetch you), you’ll save me a walk.’

Stephen, whose way had been in the contrary direction, turned about, and betook himself as in duty bound, to the red brick castle of the giant Bounderby.

CHAPTER V

MEN AND MASTERS

‘Well, Stephen,’ said Bounderby, in his windy manner, ‘what’s this I hear? What have these pests of the earth been doing to you? Come in, and speak up.’

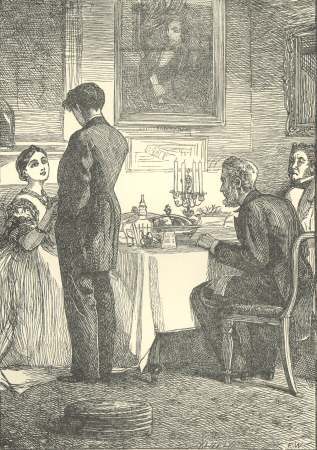

It was into the drawing-room that he was thus bidden. A tea-table was set out; and Mr. Bounderby’s young wife, and her brother, and a great gentleman from London, were present. To whom Stephen made his obeisance, closing the door and standing near it, with his hat in his hand.

‘This is the man I was telling you about, Harthouse,’ said Mr. Bounderby. The gentleman he addressed, who was talking to Mrs. Bounderby on the sofa, got up, saying in an indolent way, ‘Oh really?’ and dawdled to the hearthrug where Mr. Bounderby stood.

‘Now,’ said Bounderby, ‘speak up!’

After the four days he had passed, this address fell rudely and discordantly on Stephen’s ear. Besides being a rough handling of his wounded mind, it seemed to assume that he really was the self-interested deserter he had been called.

‘What were it, sir,’ said Stephen, ‘as yo were pleased to want wi’ me?’

‘Why, I have told you,’ returned Bounderby. ‘Speak up like a man, since you are a man, and tell us about yourself and this Combination.’

‘Wi’ yor pardon, sir,’ said Stephen Blackpool, ‘I ha’ nowt to sen about it.’

Mr. Bounderby, who was always more or less like a Wind, finding something in his way here, began to blow at it directly.

‘Now, look here, Harthouse,’ said he, ‘here’s a specimen of ’em. When this man was here once before, I warned this man against the mischievous strangers who are always about—and who ought to be hanged wherever they are found—and I told this man that he was going in the wrong direction. Now, would you believe it, that although they have put this mark upon him, he is such a slave to them still, that he’s afraid to open his lips about them?’

‘I sed as I had nowt to sen, sir; not as I was fearfo’ o’ openin’ my lips.’

‘You said! Ah! I know what you said; more than that, I know what you mean, you see. Not always the same thing, by the Lord Harry! Quite different things. You had better tell us at once, that that fellow Slackbridge is not in the town, stirring up the people to mutiny; and that he is not a regular qualified leader of the people: that is, a most confounded scoundrel. You had better tell us so at once; you can’t deceive me. You want to tell us so. Why don’t you?’

‘I’m as sooary as yo, sir, when the people’s leaders is bad,’ said Stephen, shaking his head. ‘They taks such as offers. Haply ’tis na’ the sma’est o’ their misfortuns when they can get no better.’

The wind began to get boisterous.

‘Now, you’ll think this pretty well, Harthouse,’ said Mr. Bounderby. ‘You’ll think this tolerably strong. You’ll say, upon my soul this is a tidy specimen of what my friends have to deal with; but this is nothing, sir! You shall hear me ask this man a question. Pray, Mr. Blackpool’—wind springing up very fast—‘may I take the liberty of asking you how it happens that you refused to be in this Combination?’

‘How ’t happens?’

‘Ah!’ said Mr. Bounderby, with his thumbs in the arms of his coat, and jerking his head and shutting his eyes in confidence with the opposite wall: ‘how it happens.’

‘I’d leefer not coom to ’t, sir; but sin you put th’ question—an’ not want’n t’ be ill-manner’n—I’ll answer. I ha passed a promess.’

‘Not to me, you know,’ said Bounderby. (Gusty weather with deceitful calms. One now prevailing.)

‘O no, sir. Not to yo.’

‘As for me, any consideration for me has had just nothing at all to do with it,’ said Bounderby, still in confidence with the wall. ‘If only Josiah Bounderby of Coketown had been in question, you would have joined and made no bones about it?’

‘Why yes, sir. ’Tis true.’

‘Though he knows,’ said Mr. Bounderby, now blowing a gale, ‘that there are a set of rascals and rebels whom transportation is too good for! Now, Mr. Harthouse, you have been knocking about in the world some time. Did you ever meet with anything like that man out of this blessed country?’ And Mr. Bounderby pointed him out for inspection, with an angry finger.

‘Nay, ma’am,’ said Stephen Blackpool, staunchly protesting against the words that had been used, and instinctively addressing himself to Louisa, after glancing at her face. ‘Not rebels, nor yet rascals. Nowt o’ th’ kind, ma’am, nowt o’ th’ kind. They’ve not doon me a kindness, ma’am, as I know and feel. But there’s not a dozen men amoong ’em, ma’am—a dozen? Not six—but what believes as he has doon his duty by the rest and by himseln. God forbid as I, that ha’ known, and had’n experience o’ these men aw my life—I, that ha’ ett’n an’ droonken wi’ ’em, an’ seet’n wi’ ’em, and toil’n wi’ ’em, and lov’n ’em, should fail fur to stan by ’em wi’ the truth, let ’em ha’ doon to me what they may!’

He spoke with the rugged earnestness of his place and character—deepened perhaps by a proud consciousness that he was faithful to his class under all their mistrust; but he fully remembered where he was, and did not even raise his voice.

‘No, ma’am, no. They’re true to one another, faithfo’ to one another, ’fectionate to one another, e’en to death. Be poor amoong ’em, be sick amoong ’em, grieve amoong ’em for onny o’ th’ monny causes that carries grief to the poor man’s door, an’ they’ll be tender wi’ yo, gentle wi’ yo, comfortable wi’ yo, Chrisen wi’ yo. Be sure o’ that, ma’am. They’d be riven to bits, ere ever they’d be different.’

‘In short,’ said Mr. Bounderby, ‘it’s because they are so full of virtues that they have turned you adrift. Go through with it while you are about it. Out with it.’

‘How ’tis, ma’am,’ resumed Stephen, appearing still to find his natural refuge in Louisa’s face, ‘that what is best in us fok, seems to turn us most to trouble an’ misfort’n an’ mistake, I dunno. But ’tis so. I know ’tis, as I know the heavens is over me ahint the smoke. We’re patient too, an’ wants in general to do right. An’ I canna think the fawt is aw wi’ us.’

‘Now, my friend,’ said Mr. Bounderby, whom he could not have exasperated more, quite unconscious of it though he was, than by seeming to appeal to any one else, ‘if you will favour me with your attention for half a minute, I should like to have a word or two with you. You said just now, that you had nothing to tell us about this business. You are quite sure of that before we go any further.’

‘Sir, I am sure on ’t.’

‘Here’s a gentleman from London present,’ Mr. Bounderby made a backhanded point at Mr. James Harthouse with his thumb, ‘a Parliament gentleman. I should like him to hear a short bit of dialogue between you and me, instead of taking the substance of it—for I know precious well, beforehand, what it will be; nobody knows better than I do, take notice!—instead of receiving it on trust from my mouth.’

Stephen bent his head to the gentleman from London, and showed a rather more troubled mind than usual. He turned his eyes involuntarily to his former refuge, but at a look from that quarter (expressive though instantaneous) he settled them on Mr. Bounderby’s face.

‘Now, what do you complain of?’ asked Mr. Bounderby.

‘I ha’ not coom here, sir,’ Stephen reminded him, ‘to complain. I coom for that I were sent for.’

‘What,’ repeated Mr. Bounderby, folding his arms, ‘do you people, in a general way, complain of?’

Stephen looked at him with some little irresolution for a moment, and then seemed to make up his mind.

‘Sir, I were never good at showin o ’t, though I ha had’n my share in feeling o ’t. ’Deed we are in a muddle, sir. Look round town—so rich as ’tis—and see the numbers o’ people as has been broughten into bein heer, fur to weave, an’ to card, an’ to piece out a livin’, aw the same one way, somehows, ’twixt their cradles and their graves. Look how we live, an’ wheer we live, an’ in what numbers, an’ by what chances, and wi’ what sameness; and look how the mills is awlus a goin, and how they never works us no nigher to ony dis’ant object—ceptin awlus, Death. Look how you considers of us, and writes of us, and talks of us, and goes up wi’ yor deputations to Secretaries o’ State ’bout us, and how yo are awlus right, and how we are awlus wrong, and never had’n no reason in us sin ever we were born. Look how this ha growen an’ growen, sir, bigger an’ bigger, broader an’ broader, harder an’ harder, fro year to year, fro generation unto generation. Who can look on ’t, sir, and fairly tell a man ’tis not a muddle?’

‘Of course,’ said Mr. Bounderby. ‘Now perhaps you’ll let the gentleman know, how you would set this muddle (as you’re so fond of calling it) to rights.’

‘I donno, sir. I canna be expecten to ’t. ’Tis not me as should be looken to for that, sir. ’Tis them as is put ower me, and ower aw the rest of us. What do they tak upon themseln, sir, if not to do’t?’

‘I’ll tell you something towards it, at any rate,’ returned Mr. Bounderby. ‘We will make an example of half a dozen Slackbridges. We’ll indict the blackguards for felony, and get ’em shipped off to penal settlements.’

Stephen gravely shook his head.

‘Don’t tell me we won’t, man,’ said Mr. Bounderby, by this time blowing a hurricane, ‘because we will, I tell you!’

‘Sir,’ returned Stephen, with the quiet confidence of absolute certainty, ‘if yo was t’ tak a hundred Slackbridges—aw as there is, and aw the number ten times towd—an’ was t’ sew ’em up in separate sacks, an’ sink ’em in the deepest ocean as were made ere ever dry land coom to be, yo’d leave the muddle just wheer ’tis. Mischeevous strangers!’ said Stephen, with an anxious smile; ‘when ha we not heern, I am sure, sin ever we can call to mind, o’ th’ mischeevous strangers! ’Tis not by them the trouble’s made, sir. ’Tis not wi’ them ’t commences. I ha no favour for ’em—I ha no reason to favour ’em—but ’tis hopeless and useless to dream o’ takin them fro their trade, ’stead o’ takin their trade fro them! Aw that’s now about me in this room were heer afore I coom, an’ will be heer when I am gone. Put that clock aboard a ship an’ pack it off to Norfolk Island, an’ the time will go on just the same. So ’tis wi’ Slackbridge every bit.’

Reverting for a moment to his former refuge, he observed a cautionary movement of her eyes towards the door. Stepping back, he put his hand upon the lock. But he had not spoken out of his own will and desire; and he felt it in his heart a noble return for his late injurious treatment to be faithful to the last to those who had repudiated him. He stayed to finish what was in his mind.

‘Sir, I canna, wi’ my little learning an’ my common way, tell the genelman what will better aw this—though some working men o’ this town could, above my powers—but I can tell him what I know will never do ’t. The strong hand will never do ’t. Vict’ry and triumph will never do ’t. Agreeing fur to mak one side unnat’rally awlus and for ever right, and toother side unnat’rally awlus and for ever wrong, will never, never do ’t. Nor yet lettin alone will never do ’t. Let thousands upon thousands alone, aw leading the like lives and aw faw’en into the like muddle, and they will be as one, and yo will be as anoother, wi’ a black unpassable world betwixt yo, just as long or short a time as sich-like misery can last. Not drawin nigh to fok, wi’ kindness and patience an’ cheery ways, that so draws nigh to one another in their monny troubles, and so cherishes one another in their distresses wi’ what they need themseln—like, I humbly believe, as no people the genelman ha seen in aw his travels can beat—will never do ’t till th’ Sun turns t’ ice. Most o’ aw, rating ’em as so much Power, and reg’latin ’em as if they was figures in a soom, or machines: wi’out loves and likens, wi’out memories and inclinations, wi’out souls to weary and souls to hope—when aw goes quiet, draggin on wi’ ’em as if they’d nowt o’ th’ kind, and when aw goes onquiet, reproachin ’em for their want o’ sitch humanly feelins in their dealins wi’ yo—this will never do ’t, sir, till God’s work is onmade.’

Stephen stood with the open door in his hand, waiting to know if anything more were expected of him.

‘Just stop a moment,’ said Mr. Bounderby, excessively red in the face. ‘I told you, the last time you were here with a grievance, that you had better turn about and come out of that. And I also told you, if you remember, that I was up to the gold spoon look-out.’

‘I were not up to ’t myseln, sir; I do assure yo.’

‘Now it’s clear to me,’ said Mr. Bounderby, ‘that you are one of those chaps who have always got a grievance. And you go about, sowing it and raising crops. That’s the business of your life, my friend.’

Stephen shook his head, mutely protesting that indeed he had other business to do for his life.

‘You are such a waspish, raspish, ill-conditioned chap, you see,’ said Mr. Bounderby, ‘that even your own Union, the men who know you best, will have nothing to do with you. I never thought those fellows could be right in anything; but I tell you what! I so far go along with them for a novelty, that I’ll have nothing to do with you either.’

Stephen raised his eyes quickly to his face.

‘You can finish off what you’re at,’ said Mr. Bounderby, with a meaning nod, ‘and then go elsewhere.’

‘Sir, yo know weel,’ said Stephen expressively, ‘that if I canna get work wi’ yo, I canna get it elsewheer.’

The reply was, ‘What I know, I know; and what you know, you know. I have no more to say about it.’

Stephen glanced at Louisa again, but her eyes were raised to his no more; therefore, with a sigh, and saying, barely above his breath, ‘Heaven help us aw in this world!’ he departed.

CHAPTER VI

FADING AWAY

It was falling dark when Stephen came out of Mr. Bounderby’s house. The shadows of night had gathered so fast, that he did not look about him when he closed the door, but plodded straight along the street. Nothing was further from his thoughts than the curious old woman he had encountered on his previous visit to the same house, when he heard a step behind him that he knew, and turning, saw her in Rachael’s company.

He saw Rachael first, as he had heard her only.

‘Ah, Rachael, my dear! Missus, thou wi’ her!’

‘Well, and now you are surprised to be sure, and with reason I must say,’ the old woman returned. ‘Here I am again, you see.’

‘But how wi’ Rachael?’ said Stephen, falling into their step, walking between them, and looking from the one to the other.

‘Why, I come to be with this good lass pretty much as I came to be with you,’ said the old woman, cheerfully, taking the reply upon herself. ‘My visiting time is later this year than usual, for I have been rather troubled with shortness of breath, and so put it off till the weather was fine and warm. For the same reason I don’t make all my journey in one day, but divide it into two days, and get a bed to-night at the Travellers’ Coffee House down by the railroad (a nice clean house), and go back Parliamentary, at six in the morning. Well, but what has this to do with this good lass, says you? I’m going to tell you. I have heard of Mr. Bounderby being married. I read it in the paper, where it looked grand—oh, it looked fine!’ the old woman dwelt on it with strange enthusiasm: ‘and I want to see his wife. I have never seen her yet. Now, if you’ll believe me, she hasn’t come out of that house since noon to-day. So not to give her up too easily, I was waiting about, a little last bit more, when I passed close to this good lass two or three times; and her face being so friendly I spoke to her, and she spoke to me. There!’ said the old woman to Stephen, ‘you can make all the rest out for yourself now, a deal shorter than I can, I dare say!’

Once again, Stephen had to conquer an instinctive propensity to dislike this old woman, though her manner was as honest and simple as a manner possibly could be. With a gentleness that was as natural to him as he knew it to be to Rachael, he pursued the subject that interested her in her old age.

‘Well, missus,’ said he, ‘I ha seen the lady, and she were young and hansom. Wi’ fine dark thinkin eyes, and a still way, Rachael, as I ha never seen the like on.’

‘Young and handsome. Yes!’ cried the old woman, quite delighted. ‘As bonny as a rose! And what a happy wife!’

‘Aye, missus, I suppose she be,’ said Stephen. But with a doubtful glance at Rachael.

‘Suppose she be? She must be. She’s your master’s wife,’ returned the old woman.

Stephen nodded assent. ‘Though as to master,’ said he, glancing again at Rachael, ‘not master onny more. That’s aw enden ’twixt him and me.’

‘Have you left his work, Stephen?’ asked Rachael, anxiously and quickly.

‘Why, Rachael,’ he replied, ‘whether I ha lef’n his work, or whether his work ha lef’n me, cooms t’ th’ same. His work and me are parted. ’Tis as weel so—better, I were thinkin when yo coom up wi’ me. It would ha brought’n trouble upon trouble if I had stayed theer. Haply ’tis a kindness to monny that I go; haply ’tis a kindness to myseln; anyways it mun be done. I mun turn my face fro Coketown fur th’ time, and seek a fort’n, dear, by beginnin fresh.’

‘Where will you go, Stephen?’

‘I donno t’night,’ said he, lifting off his hat, and smoothing his thin hair with the flat of his hand. ‘But I’m not goin t’night, Rachael, nor yet t’morrow. ’Tan’t easy overmuch t’ know wheer t’ turn, but a good heart will coom to me.’

Herein, too, the sense of even thinking unselfishly aided him. Before he had so much as closed Mr. Bounderby’s door, he had reflected that at least his being obliged to go away was good for her, as it would save her from the chance of being brought into question for not withdrawing from him. Though it would cost him a hard pang to leave her, and though he could think of no similar place in which his condemnation would not pursue him, perhaps it was almost a relief to be forced away from the endurance of the last four days, even to unknown difficulties and distresses.

So he said, with truth, ‘I’m more leetsome, Rachael, under ’t, than I could’n ha believed.’ It was not her part to make his burden heavier. She answered with her comforting smile, and the three walked on together.

Age, especially when it strives to be self-reliant and cheerful, finds much consideration among the poor. The old woman was so decent and contented, and made so light of her infirmities, though they had increased upon her since her former interview with Stephen, that they both took an interest in her. She was too sprightly to allow of their walking at a slow pace on her account, but she was very grateful to be talked to, and very willing to talk to any extent: so, when they came to their part of the town, she was more brisk and vivacious than ever.

‘Come to my poor place, missus,’ said Stephen, ‘and tak a coop o’ tea. Rachael will coom then; and arterwards I’ll see thee safe t’ thy Travellers’ lodgin. ’T may be long, Rachael, ere ever I ha th’ chance o’ thy coompany agen.’

They complied, and the three went on to the house where he lodged. When they turned into a narrow street, Stephen glanced at his window with a dread that always haunted his desolate home; but it was open, as he had left it, and no one was there. The evil spirit of his life had flitted away again, months ago, and he had heard no more of her since. The only evidence of her last return now, were the scantier moveables in his room, and the grayer hair upon his head.

He lighted a candle, set out his little tea-board, got hot water from below, and brought in small portions of tea and sugar, a loaf, and some butter from the nearest shop. The bread was new and crusty, the butter fresh, and the sugar lump, of course—in fulfilment of the standard testimony of the Coketown magnates, that these people lived like princes, sir. Rachael made the tea (so large a party necessitated the borrowing of a cup), and the visitor enjoyed it mightily. It was the first glimpse of sociality the host had had for many days. He too, with the world a wide heath before him, enjoyed the meal—again in corroboration of the magnates, as exemplifying the utter want of calculation on the part of these people, sir.

‘I ha never thowt yet, missus,’ said Stephen, ‘o’ askin thy name.’

The old lady announced herself as ‘Mrs. Pegler.’

‘A widder, I think?’ said Stephen.

‘Oh, many long years!’ Mrs. Pegler’s husband (one of the best on record) was already dead, by Mrs. Pegler’s calculation, when Stephen was born.

‘’Twere a bad job, too, to lose so good a one,’ said Stephen. ‘Onny children?’

Mrs. Pegler’s cup, rattling against her saucer as she held it, denoted some nervousness on her part. ‘No,’ she said. ‘Not now, not now.’

‘Dead, Stephen,’ Rachael softly hinted.

‘I’m sooary I ha spok’n on ’t,’ said Stephen, ‘I ought t’ hadn in my mind as I might touch a sore place. I—I blame myseln.’

While he excused himself, the old lady’s cup rattled more and more. ‘I had a son,’ she said, curiously distressed, and not by any of the usual appearances of sorrow; ‘and he did well, wonderfully well. But he is not to be spoken of if you please. He is—’ Putting down her cup, she moved her hands as if she would have added, by her action, ‘dead!’ Then she said aloud, ‘I have lost him.’

Stephen had not yet got the better of his having given the old lady pain, when his landlady came stumbling up the narrow stairs, and calling him to the door, whispered in his ear. Mrs. Pegler was by no means deaf, for she caught a word as it was uttered.

‘Bounderby!’ she cried, in a suppressed voice, starting up from the table. ‘Oh hide me! Don’t let me be seen for the world. Don’t let him come up till I’ve got away. Pray, pray!’ She trembled, and was excessively agitated; getting behind Rachael, when Rachael tried to reassure her; and not seeming to know what she was about.

‘But hearken, missus, hearken,’ said Stephen, astonished. ‘’Tisn’t Mr. Bounderby; ’tis his wife. Yo’r not fearfo’ o’ her. Yo was hey-go-mad about her, but an hour sin.’

‘But are you sure it’s the lady, and not the gentleman?’ she asked, still trembling.

‘Certain sure!’

‘Well then, pray don’t speak to me, nor yet take any notice of me,’ said the old woman. ‘Let me be quite to myself in this corner.’

Stephen nodded; looking to Rachael for an explanation, which she was quite unable to give him; took the candle, went downstairs, and in a few moments returned, lighting Louisa into the room. She was followed by the whelp.

Rachael had risen, and stood apart with her shawl and bonnet in her hand, when Stephen, himself profoundly astonished by this visit, put the candle on the table. Then he too stood, with his doubled hand upon the table near it, waiting to be addressed.

For the first time in her life Louisa had come into one of the dwellings of the Coketown Hands; for the first time in her life she was face to face with anything like individuality in connection with them. She knew of their existence by hundreds and by thousands. She knew what results in work a given number of them would produce in a given space of time. She knew them in crowds passing to and from their nests, like ants or beetles. But she knew from her reading infinitely more of the ways of toiling insects than of these toiling men and women.

Something to be worked so much and paid so much, and there ended; something to be infallibly settled by laws of supply and demand; something that blundered against those laws, and floundered into difficulty; something that was a little pinched when wheat was dear, and over-ate itself when wheat was cheap; something that increased at such a rate of percentage, and yielded such another percentage of crime, and such another percentage of pauperism; something wholesale, of which vast fortunes were made; something that occasionally rose like a sea, and did some harm and waste (chiefly to itself), and fell again; this she knew the Coketown Hands to be. But, she had scarcely thought more of separating them into units, than of separating the sea itself into its component drops.

She stood for some moments looking round the room. From the few chairs, the few books, the common prints, and the bed, she glanced to the two women, and to Stephen.

‘I have come to speak to you, in consequence of what passed just now. I should like to be serviceable to you, if you will let me. Is this your wife?’

Rachael raised her eyes, and they sufficiently answered no, and dropped again.

‘I remember,’ said Louisa, reddening at her mistake; ‘I recollect, now, to have heard your domestic misfortunes spoken of, though I was not attending to the particulars at the time. It was not my meaning to ask a question that would give pain to any one here. If I should ask any other question that may happen to have that result, give me credit, if you please, for being in ignorance how to speak to you as I ought.’

As Stephen had but a little while ago instinctively addressed himself to her, so she now instinctively addressed herself to Rachael. Her manner was short and abrupt, yet faltering and timid.

‘He has told you what has passed between himself and my husband? You would be his first resource, I think.’

‘I have heard the end of it, young lady,’ said Rachael.

‘Did I understand, that, being rejected by one employer, he would probably be rejected by all? I thought he said as much?’

‘The chances are very small, young lady—next to nothing—for a man who gets a bad name among them.’

‘What shall I understand that you mean by a bad name?’

‘The name of being troublesome.’

‘Then, by the prejudices of his own class, and by the prejudices of the other, he is sacrificed alike? Are the two so deeply separated in this town, that there is no place whatever for an honest workman between them?’

Rachael shook her head in silence.

‘He fell into suspicion,’ said Louisa, ‘with his fellow-weavers, because—he had made a promise not to be one of them. I think it must have been to you that he made that promise. Might I ask you why he made it?’

Rachael burst into tears. ‘I didn’t seek it of him, poor lad. I prayed him to avoid trouble for his own good, little thinking he’d come to it through me. But I know he’d die a hundred deaths, ere ever he’d break his word. I know that of him well.’

Stephen had remained quietly attentive, in his usual thoughtful attitude, with his hand at his chin. He now spoke in a voice rather less steady than usual.

‘No one, excepting myseln, can ever know what honour, an’ what love, an’ respect, I bear to Rachael, or wi’ what cause. When I passed that promess, I towd her true, she were th’ Angel o’ my life. ’Twere a solemn promess. ’Tis gone fro’ me, for ever.’

Louisa turned her head to him, and bent it with a deference that was new in her. She looked from him to Rachael, and her features softened. ‘What will you do?’ she asked him. And her voice had softened too.

‘Weel, ma’am,’ said Stephen, making the best of it, with a smile; ‘when I ha finished off, I mun quit this part, and try another. Fortnet or misfortnet, a man can but try; there’s nowt to be done wi’out tryin’—cept laying down and dying.’

‘How will you travel?’

‘Afoot, my kind ledy, afoot.’

Louisa coloured, and a purse appeared in her hand. The rustling of a bank-note was audible, as she unfolded one and laid it on the table.

‘Rachael, will you tell him—for you know how, without offence—that this is freely his, to help him on his way? Will you entreat him to take it?’

‘I canna do that, young lady,’ she answered, turning her head aside. ‘Bless you for thinking o’ the poor lad wi’ such tenderness. But ’tis for him to know his heart, and what is right according to it.’

Louisa looked, in part incredulous, in part frightened, in part overcome with quick sympathy, when this man of so much self-command, who had been so plain and steady through the late interview, lost his composure in a moment, and now stood with his hand before his face. She stretched out hers, as if she would have touched him; then checked herself, and remained still.

‘Not e’en Rachael,’ said Stephen, when he stood again with his face uncovered, ‘could mak sitch a kind offerin, by onny words, kinder. T’ show that I’m not a man wi’out reason and gratitude, I’ll tak two pound. I’ll borrow ’t for t’ pay ’t back. ’Twill be the sweetest work as ever I ha done, that puts it in my power t’ acknowledge once more my lastin thankfulness for this present action.’

She was fain to take up the note again, and to substitute the much smaller sum he had named. He was neither courtly, nor handsome, nor picturesque, in any respect; and yet his manner of accepting it, and of expressing his thanks without more words, had a grace in it that Lord Chesterfield could not have taught his son in a century.

Tom had sat upon the bed, swinging one leg and sucking his walking-stick with sufficient unconcern, until the visit had attained this stage. Seeing his sister ready to depart, he got up, rather hurriedly, and put in a word.

‘Just wait a moment, Loo! Before we go, I should like to speak to him a moment. Something comes into my head. If you’ll step out on the stairs, Blackpool, I’ll mention it. Never mind a light, man!’ Tom was remarkably impatient of his moving towards the cupboard, to get one. ‘It don’t want a light.’

Stephen followed him out, and Tom closed the room door, and held the lock in his hand.

‘I say!’ he whispered. ‘I think I can do you a good turn. Don’t ask me what it is, because it may not come to anything. But there’s no harm in my trying.’

His breath fell like a flame of fire on Stephen’s ear, it was so hot.

‘That was our light porter at the Bank,’ said Tom, ‘who brought you the message to-night. I call him our light porter, because I belong to the Bank too.’

Stephen thought, ‘What a hurry he is in!’ He spoke so confusedly.

‘Well!’ said Tom. ‘Now look here! When are you off?’

‘T’ day’s Monday,’ replied Stephen, considering. ‘Why, sir, Friday or Saturday, nigh ’bout.’

‘Friday or Saturday,’ said Tom. ‘Now look here! I am not sure that I can do you the good turn I want to do you—that’s my sister, you know, in your room—but I may be able to, and if I should not be able to, there’s no harm done. So I tell you what. You’ll know our light porter again?’

‘Yes, sure,’ said Stephen.

‘Very well,’ returned Tom. ‘When you leave work of a night, between this and your going away, just hang about the Bank an hour or so, will you? Don’t take on, as if you meant anything, if he should see you hanging about there; because I shan’t put him up to speak to you, unless I find I can do you the service I want to do you. In that case he’ll have a note or a message for you, but not else. Now look here! You are sure you understand.’

He had wormed a finger, in the darkness, through a button-hole of Stephen’s coat, and was screwing that corner of the garment tight up round and round, in an extraordinary manner.

‘I understand, sir,’ said Stephen.

‘Now look here!’ repeated Tom. ‘Be sure you don’t make any mistake then, and don’t forget. I shall tell my sister as we go home, what I have in view, and she’ll approve, I know. Now look here! You’re all right, are you? You understand all about it? Very well then. Come along, Loo!’

He pushed the door open as he called to her, but did not return into the room, or wait to be lighted down the narrow stairs. He was at the bottom when she began to descend, and was in the street before she could take his arm.

Mrs. Pegler remained in her corner until the brother and sister were gone, and until Stephen came back with the candle in his hand. She was in a state of inexpressible admiration of Mrs. Bounderby, and, like an unaccountable old woman, wept, ‘because she was such a pretty dear.’ Yet Mrs. Pegler was so flurried lest the object of her admiration should return by chance, or anybody else should come, that her cheerfulness was ended for that night. It was late too, to people who rose early and worked hard; therefore the party broke up; and Stephen and Rachael escorted their mysterious acquaintance to the door of the Travellers’ Coffee House, where they parted from her.

They walked back together to the corner of the street where Rachael lived, and as they drew nearer and nearer to it, silence crept upon them. When they came to the dark corner where their unfrequent meetings always ended, they stopped, still silent, as if both were afraid to speak.

‘I shall strive t’ see thee agen, Rachael, afore I go, but if not—’

‘Thou wilt not, Stephen, I know. ’Tis better that we make up our minds to be open wi’ one another.’

‘Thou’rt awlus right. ’Tis bolder and better. I ha been thinkin then, Rachael, that as ’tis but a day or two that remains, ’twere better for thee, my dear, not t’ be seen wi’ me. ’T might bring thee into trouble, fur no good.’

‘’Tis not for that, Stephen, that I mind. But thou know’st our old agreement. ’Tis for that.’

‘Well, well,’ said he. ‘’Tis better, onnyways.’

‘Thou’lt write to me, and tell me all that happens, Stephen?’

‘Yes. What can I say now, but Heaven be wi’ thee, Heaven bless thee, Heaven thank thee and reward thee!’

‘May it bless thee, Stephen, too, in all thy wanderings, and send thee peace and rest at last!’

‘I towd thee, my dear,’ said Stephen Blackpool—‘that night—that I would never see or think o’ onnything that angered me, but thou, so much better than me, should’st be beside it. Thou’rt beside it now. Thou mak’st me see it wi’ a better eye. Bless thee. Good night. Good-bye!’

It was but a hurried parting in a common street, yet it was a sacred remembrance to these two common people. Utilitarian economists, skeletons of schoolmasters, Commissioners of Fact, genteel and used-up infidels, gabblers of many little dog’s-eared creeds, the poor you will have always with you. Cultivate in them, while there is yet time, the utmost graces of the fancies and affections, to adorn their lives so much in need of ornament; or, in the day of your triumph, when romance is utterly driven out of their souls, and they and a bare existence stand face to face, Reality will take a wolfish turn, and make an end of you.

Stephen worked the next day, and the next, uncheered by a word from any one, and shunned in all his comings and goings as before. At the end of the second day, he saw land; at the end of the third, his loom stood empty.

He had overstayed his hour in the street outside the Bank, on each of the two first evenings; and nothing had happened there, good or bad. That he might not be remiss in his part of the engagement, he resolved to wait full two hours, on this third and last night.

There was the lady who had once kept Mr. Bounderby’s house, sitting at the first-floor window as he had seen her before; and there was the light porter, sometimes talking with her there, and sometimes looking over the blind below which had Bank upon it, and sometimes coming to the door and standing on the steps for a breath of air. When he first came out, Stephen thought he might be looking for him, and passed near; but the light porter only cast his winking eyes upon him slightly, and said nothing.

Two hours were a long stretch of lounging about, after a long day’s labour. Stephen sat upon the step of a door, leaned against a wall under an archway, strolled up and down, listened for the church clock, stopped and watched children playing in the street. Some purpose or other is so natural to every one, that a mere loiterer always looks and feels remarkable. When the first hour was out, Stephen even began to have an uncomfortable sensation upon him of being for the time a disreputable character.

Then came the lamplighter, and two lengthening lines of light all down the long perspective of the street, until they were blended and lost in the distance. Mrs. Sparsit closed the first-floor window, drew down the blind, and went up-stairs. Presently, a light went up-stairs after her, passing first the fanlight of the door, and afterwards the two staircase windows, on its way up. By and by, one corner of the second-floor blind was disturbed, as if Mrs. Sparsit’s eye were there; also the other corner, as if the light porter’s eye were on that side. Still, no communication was made to Stephen. Much relieved when the two hours were at last accomplished, he went away at a quick pace, as a recompense for so much loitering.

He had only to take leave of his landlady, and lie down on his temporary bed upon the floor; for his bundle was made up for to-morrow, and all was arranged for his departure. He meant to be clear of the town very early; before the Hands were in the streets.

It was barely daybreak, when, with a parting look round his room, mournfully wondering whether he should ever see it again, he went out. The town was as entirely deserted as if the inhabitants had abandoned it, rather than hold communication with him. Everything looked wan at that hour. Even the coming sun made but a pale waste in the sky, like a sad sea.

By the place where Rachael lived, though it was not in his way; by the red brick streets; by the great silent factories, not trembling yet; by the railway, where the danger-lights were waning in the strengthening day; by the railway’s crazy neighbourhood, half pulled down and half built up; by scattered red brick villas, where the besmoked evergreens were sprinkled with a dirty powder, like untidy snuff-takers; by coal-dust paths and many varieties of ugliness; Stephen got to the top of the hill, and looked back.