The consultation ended in the men returning to the windlass, and the pitman going down again, carrying the wine and some other small matters with him. Then the other man came up. In the meantime, under the surgeon’s directions, some men brought a hurdle, on which others made a thick bed of spare clothes covered with loose straw, while he himself contrived some bandages and slings from shawls and handkerchiefs. As these were made, they were hung upon an arm of the pitman who had last come up, with instructions how to use them: and as he stood, shown by the light he carried, leaning his powerful loose hand upon one of the poles, and sometimes glancing down the pit, and sometimes glancing round upon the people, he was not the least conspicuous figure in the scene. It was dark now, and torches were kindled.

It appeared from the little this man said to those about him, which was quickly repeated all over the circle, that the lost man had fallen upon a mass of crumbled rubbish with which the pit was half choked up, and that his fall had been further broken by some jagged earth at the side. He lay upon his back with one arm doubled under him, and according to his own belief had hardly stirred since he fell, except that he had moved his free hand to a side pocket, in which he remembered to have some bread and meat (of which he had swallowed crumbs), and had likewise scooped up a little water in it now and then. He had come straight away from his work, on being written to, and had walked the whole journey; and was on his way to Mr. Bounderby’s country house after dark, when he fell. He was crossing that dangerous country at such a dangerous time, because he was innocent of what was laid to his charge, and couldn’t rest from coming the nearest way to deliver himself up. The Old Hell Shaft, the pitman said, with a curse upon it, was worthy of its bad name to the last; for though Stephen could speak now, he believed it would soon be found to have mangled the life out of him.

When all was ready, this man, still taking his last hurried charges from his comrades and the surgeon after the windlass had begun to lower him, disappeared into the pit. The rope went out as before, the signal was made as before, and the windlass stopped. No man removed his hand from it now. Every one waited with his grasp set, and his body bent down to the work, ready to reverse and wind in. At length the signal was given, and all the ring leaned forward.

For, now, the rope came in, tightened and strained to its utmost as it appeared, and the men turned heavily, and the windlass complained. It was scarcely endurable to look at the rope, and think of its giving way. But, ring after ring was coiled upon the barrel of the windlass safely, and the connecting chains appeared, and finally the bucket with the two men holding on at the sides—a sight to make the head swim, and oppress the heart—and tenderly supporting between them, slung and tied within, the figure of a poor, crushed, human creature.

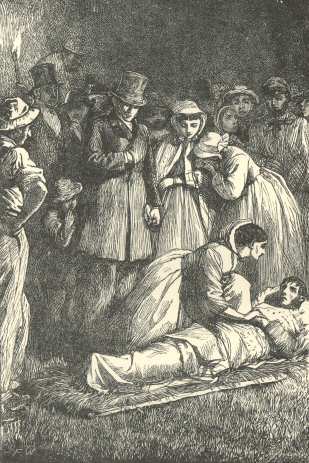

A low murmur of pity went round the throng, and the women wept aloud, as this form, almost without form, was moved very slowly from its iron deliverance, and laid upon the bed of straw. At first, none but the surgeon went close to it. He did what he could in its adjustment on the couch, but the best that he could do was to cover it. That gently done, he called to him Rachael and Sissy. And at that time the pale, worn, patient face was seen looking up at the sky, with the broken right hand lying bare on the outside of the covering garments, as if waiting to be taken by another hand.

They gave him drink, moistened his face with water, and administered some drops of cordial and wine. Though he lay quite motionless looking up at the sky, he smiled and said, ‘Rachael.’ She stooped down on the grass at his side, and bent over him until her eyes were between his and the sky, for he could not so much as turn them to look at her.

‘Rachael, my dear.’

She took his hand. He smiled again and said, ‘Don’t let ’t go.’

‘Thou’rt in great pain, my own dear Stephen?’

‘I ha’ been, but not now. I ha’ been—dreadful, and dree, and long, my dear—but ’tis ower now. Ah, Rachael, aw a muddle! Fro’ first to last, a muddle!’

The spectre of his old look seemed to pass as he said the word.

‘I ha’ fell into th’ pit, my dear, as have cost wi’in the knowledge o’ old fok now livin, hundreds and hundreds o’ men’s lives—fathers, sons, brothers, dear to thousands an’ thousands, an’ keeping ’em fro’ want and hunger. I ha’ fell into a pit that ha’ been wi’ th’ Firedamp crueller than battle. I ha’ read on ’t in the public petition, as onny one may read, fro’ the men that works in pits, in which they ha’ pray’n and pray’n the lawmakers for Christ’s sake not to let their work be murder to ’em, but to spare ’em for th’ wives and children that they loves as well as gentlefok loves theirs. When it were in work, it killed wi’out need; when ’tis let alone, it kills wi’out need. See how we die an’ no need, one way an’ another—in a muddle—every day!’

He faintly said it, without any anger against any one. Merely as the truth.

‘Thy little sister, Rachael, thou hast not forgot her. Thou’rt not like to forget her now, and me so nigh her. Thou know’st—poor, patient, suff’rin, dear—how thou didst work for her, seet’n all day long in her little chair at thy winder, and how she died, young and misshapen, awlung o’ sickly air as had’n no need to be, an’ awlung o’ working people’s miserable homes. A muddle! Aw a muddle!’

Louisa approached him; but he could not see her, lying with his face turned up to the night sky.

‘If aw th’ things that tooches us, my dear, was not so muddled, I should’n ha’ had’n need to coom heer. If we was not in a muddle among ourseln, I should’n ha’ been, by my own fellow weavers and workin’ brothers, so mistook. If Mr. Bounderby had ever know’d me right—if he’d ever know’d me at aw—he would’n ha’ took’n offence wi’ me. He would’n ha’ suspect’n me. But look up yonder, Rachael! Look aboove!’

Following his eyes, she saw that he was gazing at a star.

‘It ha’ shined upon me,’ he said reverently, ‘in my pain and trouble down below. It ha’ shined into my mind. I ha’ look’n at ’t and thowt o’ thee, Rachael, till the muddle in my mind have cleared awa, above a bit, I hope. If soom ha’ been wantin’ in unnerstan’in me better, I, too, ha’ been wantin’ in unnerstan’in them better. When I got thy letter, I easily believen that what the yoong ledy sen and done to me, and what her brother sen and done to me, was one, and that there were a wicked plot betwixt ’em. When I fell, I were in anger wi’ her, an’ hurryin on t’ be as onjust t’ her as oothers was t’ me. But in our judgments, like as in our doins, we mun bear and forbear. In my pain an’ trouble, lookin up yonder,—wi’ it shinin on me—I ha’ seen more clear, and ha’ made it my dyin prayer that aw th’ world may on’y coom toogether more, an’ get a better unnerstan’in o’ one another, than when I were in ’t my own weak seln.’

Louisa hearing what he said, bent over him on the opposite side to Rachael, so that he could see her.

‘You ha’ heard?’ he said, after a few moments’ silence. ‘I ha’ not forgot you, ledy.’

‘Yes, Stephen, I have heard you. And your prayer is mine.’

‘You ha’ a father. Will yo tak’ a message to him?’

‘He is here,’ said Louisa, with dread. ‘Shall I bring him to you?’

‘If yo please.’

Louisa returned with her father. Standing hand-in-hand, they both looked down upon the solemn countenance.

‘Sir, yo will clear me an’ mak my name good wi’ aw men. This I leave to yo.’

Mr. Gradgrind was troubled and asked how?

‘Sir,’ was the reply: ‘yor son will tell yo how. Ask him. I mak no charges: I leave none ahint me: not a single word. I ha’ seen an’ spok’n wi’ yor son, one night. I ask no more o’ yo than that yo clear me—an’ I trust to yo to do ’t.’

The bearers being now ready to carry him away, and the surgeon being anxious for his removal, those who had torches or lanterns, prepared to go in front of the litter. Before it was raised, and while they were arranging how to go, he said to Rachael, looking upward at the star:

‘Often as I coom to myseln, and found it shinin’ on me down there in my trouble, I thowt it were the star as guided to Our Saviour’s home. I awmust think it be the very star!’

They lifted him up, and he was overjoyed to find that they were about to take him in the direction whither the star seemed to him to lead.

‘Rachael, beloved lass! Don’t let go my hand. We may walk toogether t’night, my dear!’

‘I will hold thy hand, and keep beside thee, Stephen, all the way.’

‘Bless thee! Will soombody be pleased to coover my face!’

They carried him very gently along the fields, and down the lanes, and over the wide landscape; Rachael always holding the hand in hers. Very few whispers broke the mournful silence. It was soon a funeral procession. The star had shown him where to find the God of the poor; and through humility, and sorrow, and forgiveness, he had gone to his Redeemer’s rest.

CHAPTER VII

WHELP-HUNTING

Before the ring formed round the Old Hell Shaft was broken, one figure had disappeared from within it. Mr. Bounderby and his shadow had not stood near Louisa, who held her father’s arm, but in a retired place by themselves. When Mr. Gradgrind was summoned to the couch, Sissy, attentive to all that happened, slipped behind that wicked shadow—a sight in the horror of his face, if there had been eyes there for any sight but one—and whispered in his ear. Without turning his head, he conferred with her a few moments, and vanished. Thus the whelp had gone out of the circle before the people moved.

When the father reached home, he sent a message to Mr. Bounderby’s, desiring his son to come to him directly. The reply was, that Mr. Bounderby having missed him in the crowd, and seeing nothing of him since, had supposed him to be at Stone Lodge.

‘I believe, father,’ said Louisa, ‘he will not come back to town to-night.’ Mr. Gradgrind turned away, and said no more.

In the morning, he went down to the Bank himself as soon as it was opened, and seeing his son’s place empty (he had not the courage to look in at first) went back along the street to meet Mr. Bounderby on his way there. To whom he said that, for reasons he would soon explain, but entreated not then to be asked for, he had found it necessary to employ his son at a distance for a little while. Also, that he was charged with the duty of vindicating Stephen Blackpool’s memory, and declaring the thief. Mr. Bounderby quite confounded, stood stock-still in the street after his father-in-law had left him, swelling like an immense soap-bubble, without its beauty.

Mr. Gradgrind went home, locked himself in his room, and kept it all that day. When Sissy and Louisa tapped at his door, he said, without opening it, ‘Not now, my dears; in the evening.’ On their return in the evening, he said, ‘I am not able yet—to-morrow.’ He ate nothing all day, and had no candle after dark; and they heard him walking to and fro late at night.

But, in the morning he appeared at breakfast at the usual hour, and took his usual place at the table. Aged and bent he looked, and quite bowed down; and yet he looked a wiser man, and a better man, than in the days when in this life he wanted nothing—but Facts. Before he left the room, he appointed a time for them to come to him; and so, with his gray head drooping, went away.

‘Dear father,’ said Louisa, when they kept their appointment, ‘you have three young children left. They will be different, I will be different yet, with Heaven’s help.’

She gave her hand to Sissy, as if she meant with her help too.

‘Your wretched brother,’ said Mr. Gradgrind. ‘Do you think he had planned this robbery, when he went with you to the lodging?’

‘I fear so, father. I know he had wanted money very much, and had spent a great deal.’

‘The poor man being about to leave the town, it came into his evil brain to cast suspicion on him?’

‘I think it must have flashed upon him while he sat there, father. For I asked him to go there with me. The visit did not originate with him.’

‘He had some conversation with the poor man. Did he take him aside?’

‘He took him out of the room. I asked him afterwards, why he had done so, and he made a plausible excuse; but since last night, father, and when I remember the circumstances by its light, I am afraid I can imagine too truly what passed between them.’

‘Let me know,’ said her father, ‘if your thoughts present your guilty brother in the same dark view as mine.’

‘I fear, father,’ hesitated Louisa, ‘that he must have made some representation to Stephen Blackpool—perhaps in my name, perhaps in his own—which induced him to do in good faith and honesty, what he had never done before, and to wait about the Bank those two or three nights before he left the town.’

‘Too plain!’ returned the father. ‘Too plain!’

He shaded his face, and remained silent for some moments. Recovering himself, he said:

‘And now, how is he to be found? How is he to be saved from justice? In the few hours that I can possibly allow to elapse before I publish the truth, how is he to be found by us, and only by us? Ten thousand pounds could not effect it.’

‘Sissy has effected it, father.’

He raised his eyes to where she stood, like a good fairy in his house, and said in a tone of softened gratitude and grateful kindness, ‘It is always you, my child!’

‘We had our fears,’ Sissy explained, glancing at Louisa, ‘before yesterday; and when I saw you brought to the side of the litter last night, and heard what passed (being close to Rachael all the time), I went to him when no one saw, and said to him, “Don’t look at me. See where your father is. Escape at once, for his sake and your own!” He was in a tremble before I whispered to him, and he started and trembled more then, and said, “Where can I go? I have very little money, and I don’t know who will hide me!” I thought of father’s old circus. I have not forgotten where Mr. Sleary goes at this time of year, and I read of him in a paper only the other day. I told him to hurry there, and tell his name, and ask Mr. Sleary to hide him till I came. “I’ll get to him before the morning,” he said. And I saw him shrink away among the people.’

‘Thank Heaven!’ exclaimed his father. ‘He may be got abroad yet.’

It was the more hopeful as the town to which Sissy had directed him was within three hours’ journey of Liverpool, whence he could be swiftly dispatched to any part of the world. But, caution being necessary in communicating with him—for there was a greater danger every moment of his being suspected now, and nobody could be sure at heart but that Mr. Bounderby himself, in a bullying vein of public zeal, might play a Roman part—it was consented that Sissy and Louisa should repair to the place in question, by a circuitous course, alone; and that the unhappy father, setting forth in an opposite direction, should get round to the same bourne by another and wider route. It was further agreed that he should not present himself to Mr. Sleary, lest his intentions should be mistrusted, or the intelligence of his arrival should cause his son to take flight anew; but, that the communication should be left to Sissy and Louisa to open; and that they should inform the cause of so much misery and disgrace, of his father’s being at hand and of the purpose for which they had come. When these arrangements had been well considered and were fully understood by all three, it was time to begin to carry them into execution. Early in the afternoon, Mr. Gradgrind walked direct from his own house into the country, to be taken up on the line by which he was to travel; and at night the remaining two set forth upon their different course, encouraged by not seeing any face they knew.

The two travelled all night, except when they were left, for odd numbers of minutes, at branch-places, up illimitable flights of steps, or down wells—which was the only variety of those branches—and, early in the morning, were turned out on a swamp, a mile or two from the town they sought. From this dismal spot they were rescued by a savage old postilion, who happened to be up early, kicking a horse in a fly: and so were smuggled into the town by all the back lanes where the pigs lived: which, although not a magnificent or even savoury approach, was, as is usual in such cases, the legitimate highway.

The first thing they saw on entering the town was the skeleton of Sleary’s Circus. The company had departed for another town more than twenty miles off, and had opened there last night. The connection between the two places was by a hilly turnpike-road, and the travelling on that road was very slow. Though they took but a hasty breakfast, and no rest (which it would have been in vain to seek under such anxious circumstances), it was noon before they began to find the bills of Sleary’s Horse-riding on barns and walls, and one o’clock when they stopped in the market-place.

A Grand Morning Performance by the Riders, commencing at that very hour, was in course of announcement by the bellman as they set their feet upon the stones of the street. Sissy recommended that, to avoid making inquiries and attracting attention in the town, they should present themselves to pay at the door. If Mr. Sleary were taking the money, he would be sure to know her, and would proceed with discretion. If he were not, he would be sure to see them inside; and, knowing what he had done with the fugitive, would proceed with discretion still.

Therefore, they repaired, with fluttering hearts, to the well-remembered booth. The flag with the inscription Sleary’s Horse-riding was there; and the Gothic niche was there; but Mr. Sleary was not there. Master Kidderminster, grown too maturely turfy to be received by the wildest credulity as Cupid any more, had yielded to the invincible force of circumstances (and his beard), and, in the capacity of a man who made himself generally useful, presided on this occasion over the exchequer—having also a drum in reserve, on which to expend his leisure moments and superfluous forces. In the extreme sharpness of his look out for base coin, Mr. Kidderminster, as at present situated, never saw anything but money; so Sissy passed him unrecognised, and they went in.

The Emperor of Japan, on a steady old white horse stencilled with black spots, was twirling five wash-hand basins at once, as it is the favourite recreation of that monarch to do. Sissy, though well acquainted with his Royal line, had no personal knowledge of the present Emperor, and his reign was peaceful. Miss Josephine Sleary, in her celebrated graceful Equestrian Tyrolean Flower Act, was then announced by a new clown (who humorously said Cauliflower Act), and Mr. Sleary appeared, leading her in.

Mr. Sleary had only made one cut at the Clown with his long whip-lash, and the Clown had only said, ‘If you do it again, I’ll throw the horse at you!’ when Sissy was recognised both by father and daughter. But they got through the Act with great self-possession; and Mr. Sleary, saving for the first instant, conveyed no more expression into his locomotive eye than into his fixed one. The performance seemed a little long to Sissy and Louisa, particularly when it stopped to afford the Clown an opportunity of telling Mr. Sleary (who said ‘Indeed, sir!’ to all his observations in the calmest way, and with his eye on the house) about two legs sitting on three legs looking at one leg, when in came four legs, and laid hold of one leg, and up got two legs, caught hold of three legs, and threw ’em at four legs, who ran away with one leg. For, although an ingenious Allegory relating to a butcher, a three-legged stool, a dog, and a leg of mutton, this narrative consumed time; and they were in great suspense. At last, however, little fair-haired Josephine made her curtsey amid great applause; and the Clown, left alone in the ring, had just warmed himself, and said, ‘Now I’ll have a turn!’ when Sissy was touched on the shoulder, and beckoned out.

She took Louisa with her; and they were received by Mr. Sleary in a very little private apartment, with canvas sides, a grass floor, and a wooden ceiling all aslant, on which the box company stamped their approbation, as if they were coming through. ‘Thethilia,’ said Mr. Sleary, who had brandy and water at hand, ‘it doth me good to thee you. You wath alwayth a favourite with uth, and you’ve done uth credith thinth the old timeth I’m thure. You mutht thee our people, my dear, afore we thpeak of bithnith, or they’ll break their hearth—ethpethially the women. Here’th Jothphine hath been and got married to E. W. B. Childerth, and thee hath got a boy, and though he’th only three yearth old, he thtickth on to any pony you can bring againtht him. He’th named The Little Wonder of Thcolathtic Equitation; and if you don’t hear of that boy at Athley’th, you’ll hear of him at Parith. And you recollect Kidderminthter, that wath thought to be rather thweet upon yourthelf? Well. He’th married too. Married a widder. Old enough to be hith mother. Thee wath Tightrope, thee wath, and now thee’th nothing—on accounth of fat. They’ve got two children, tho we’re thtrong in the Fairy bithnith and the Nurthery dodge. If you wath to thee our Children in the Wood, with their father and mother both a dyin’ on a horthe—their uncle a retheiving of ’em ath hith wardth, upon a horthe—themthelvth both a goin’ a black-berryin’ on a horthe—and the Robinth a coming in to cover ’em with leavth, upon a horthe—you’d thay it wath the completetht thing ath ever you thet your eyeth on! And you remember Emma Gordon, my dear, ath wath a’motht a mother to you? Of courthe you do; I needn’t athk. Well! Emma, thee lotht her huthband. He wath throw’d a heavy back-fall off a Elephant in a thort of a Pagoda thing ath the Thultan of the Indieth, and he never got the better of it; and thee married a thecond time—married a Cheethemonger ath fell in love with her from the front—and he’th a Overtheer and makin’ a fortun.’

These various changes, Mr. Sleary, very short of breath now, related with great heartiness, and with a wonderful kind of innocence, considering what a bleary and brandy-and-watery old veteran he was. Afterwards he brought in Josephine, and E. W. B. Childers (rather deeply lined in the jaws by daylight), and the Little Wonder of Scholastic Equitation, and in a word, all the company. Amazing creatures they were in Louisa’s eyes, so white and pink of complexion, so scant of dress, and so demonstrative of leg; but it was very agreeable to see them crowding about Sissy, and very natural in Sissy to be unable to refrain from tears.

‘There! Now Thethilia hath kithd all the children, and hugged all the women, and thaken handth all round with all the men, clear, every one of you, and ring in the band for the thecond part!’

As soon as they were gone, he continued in a low tone. ‘Now, Thethilia, I don’t athk to know any thecreth, but I thuppothe I may conthider thith to be Mith Thquire.’

‘This is his sister. Yes.’

‘And t’other on’th daughter. That’h what I mean. Hope I thee you well, mith. And I hope the Thquire’th well?’

‘My father will be here soon,’ said Louisa, anxious to bring him to the point. ‘Is my brother safe?’

‘Thafe and thound!’ he replied. ‘I want you jutht to take a peep at the Ring, mith, through here. Thethilia, you know the dodgeth; find a thpy-hole for yourthelf.’

They each looked through a chink in the boards.

‘That’h Jack the Giant Killer—piethe of comic infant bithnith,’ said Sleary. ‘There’th a property-houthe, you thee, for Jack to hide in; there’th my Clown with a thauthepan-lid and a thpit, for Jack’th thervant; there’th little Jack himthelf in a thplendid thoot of armour; there’th two comic black thervanth twithe ath big ath the houthe, to thtand by it and to bring it in and clear it; and the Giant (a very ecthpenthive bathket one), he an’t on yet. Now, do you thee ’em all?’

‘Yes,’ they both said.

‘Look at ’em again,’ said Sleary, ‘look at ’em well. You thee em all? Very good. Now, mith;’ he put a form for them to sit on; ‘I have my opinionth, and the Thquire your father hath hith. I don’t want to know what your brother’th been up to; ith better for me not to know. All I thay ith, the Thquire hath thtood by Thethilia, and I’ll thtand by the Thquire. Your brother ith one them black thervanth.’

Louisa uttered an exclamation, partly of distress, partly of satisfaction.

‘Ith a fact,’ said Sleary, ‘and even knowin’ it, you couldn’t put your finger on him. Let the Thquire come. I thall keep your brother here after the performanth. I thant undreth him, nor yet wath hith paint off. Let the Thquire come here after the performanth, or come here yourthelf after the performanth, and you thall find your brother, and have the whole plathe to talk to him in. Never mind the lookth of him, ath long ath he’th well hid.’

Louisa, with many thanks and with a lightened load, detained Mr. Sleary no longer then. She left her love for her brother, with her eyes full of tears; and she and Sissy went away until later in the afternoon.

Mr. Gradgrind arrived within an hour afterwards. He too had encountered no one whom he knew; and was now sanguine with Sleary’s assistance, of getting his disgraced son to Liverpool in the night. As neither of the three could be his companion without almost identifying him under any disguise, he prepared a letter to a correspondent whom he could trust, beseeching him to ship the bearer off at any cost, to North or South America, or any distant part of the world to which he could be the most speedily and privately dispatched.

This done, they walked about, waiting for the Circus to be quite vacated; not only by the audience, but by the company and by the horses. After watching it a long time, they saw Mr. Sleary bring out a chair and sit down by the side-door, smoking; as if that were his signal that they might approach.

‘Your thervant, Thquire,’ was his cautious salutation as they passed in. ‘If you want me you’ll find me here. You muthn’t mind your thon having a comic livery on.’

They all three went in; and Mr. Gradgrind sat down forlorn, on the Clown’s performing chair in the middle of the ring. On one of the back benches, remote in the subdued light and the strangeness of the place, sat the villainous whelp, sulky to the last, whom he had the misery to call his son.

In a preposterous coat, like a beadle’s, with cuffs and flaps exaggerated to an unspeakable extent; in an immense waistcoat, knee-breeches, buckled shoes, and a mad cocked hat; with nothing fitting him, and everything of coarse material, moth-eaten and full of holes; with seams in his black face, where fear and heat had started through the greasy composition daubed all over it; anything so grimly, detestably, ridiculously shameful as the whelp in his comic livery, Mr. Gradgrind never could by any other means have believed in, weighable and measurable fact though it was. And one of his model children had come to this!

At first the whelp would not draw any nearer, but persisted in remaining up there by himself. Yielding at length, if any concession so sullenly made can be called yielding, to the entreaties of Sissy—for Louisa he disowned altogether—he came down, bench by bench, until he stood in the sawdust, on the verge of the circle, as far as possible, within its limits from where his father sat.

‘How was this done?’ asked the father.

‘How was what done?’ moodily answered the son.

‘This robbery,’ said the father, raising his voice upon the word.

‘I forced the safe myself over night, and shut it up ajar before I went away. I had had the key that was found, made long before. I dropped it that morning, that it might be supposed to have been used. I didn’t take the money all at once. I pretended to put my balance away every night, but I didn’t. Now you know all about it.’

‘If a thunderbolt had fallen on me,’ said the father, ‘it would have shocked me less than this!’

‘I don’t see why,’ grumbled the son. ‘So many people are employed in situations of trust; so many people, out of so many, will be dishonest. I have heard you talk, a hundred times, of its being a law. How can I help laws? You have comforted others with such things, father. Comfort yourself!’

The father buried his face in his hands, and the son stood in his disgraceful grotesqueness, biting straw: his hands, with the black partly worn away inside, looking like the hands of a monkey. The evening was fast closing in; and from time to time, he turned the whites of his eyes restlessly and impatiently towards his father. They were the only parts of his face that showed any life or expression, the pigment upon it was so thick.

‘You must be got to Liverpool, and sent abroad.’

‘I suppose I must. I can’t be more miserable anywhere,’ whimpered the whelp, ‘than I have been here, ever since I can remember. That’s one thing.’

Mr. Gradgrind went to the door, and returned with Sleary, to whom he submitted the question, How to get this deplorable object away?

‘Why, I’ve been thinking of it, Thquire. There’th not muth time to lothe, tho you muth thay yeth or no. Ith over twenty mileth to the rail. There’th a coath in half an hour, that goeth to the rail, ‘purpothe to cath the mail train. That train will take him right to Liverpool.’

‘But look at him,’ groaned Mr. Gradgrind. ‘Will any coach—’

‘I don’t mean that he thould go in the comic livery,’ said Sleary. ‘Thay the word, and I’ll make a Jothkin of him, out of the wardrobe, in five minutes.’

‘I don’t understand,’ said Mr. Gradgrind.

‘A Jothkin—a Carter. Make up your mind quick, Thquire. There’ll be beer to feth. I’ve never met with nothing but beer ath’ll ever clean a comic blackamoor.’

Mr. Gradgrind rapidly assented; Mr. Sleary rapidly turned out from a box, a smock frock, a felt hat, and other essentials; the whelp rapidly changed clothes behind a screen of baize; Mr. Sleary rapidly brought beer, and washed him white again.

‘Now,’ said Sleary, ‘come along to the coath, and jump up behind; I’ll go with you there, and they’ll thuppothe you one of my people. Thay farewell to your family, and tharp’th the word.’ With which he delicately retired.

‘Here is your letter,’ said Mr. Gradgrind. ‘All necessary means will be provided for you. Atone, by repentance and better conduct, for the shocking action you have committed, and the dreadful consequences to which it has led. Give me your hand, my poor boy, and may God forgive you as I do!’

The culprit was moved to a few abject tears by these words and their pathetic tone. But, when Louisa opened her arms, he repulsed her afresh.

‘Not you. I don’t want to have anything to say to you!’

‘O Tom, Tom, do we end so, after all my love!’

‘After all your love!’ he returned, obdurately. ‘Pretty love! Leaving old Bounderby to himself, and packing my best friend Mr. Harthouse off, and going home just when I was in the greatest danger. Pretty love that! Coming out with every word about our having gone to that place, when you saw the net was gathering round me. Pretty love that! You have regularly given me up. You never cared for me.’

‘Tharp’th the word!’ said Sleary, at the door.

They all confusedly went out: Louisa crying to him that she forgave him, and loved him still, and that he would one day be sorry to have left her so, and glad to think of these her last words, far away: when some one ran against them. Mr. Gradgrind and Sissy, who were both before him while his sister yet clung to his shoulder, stopped and recoiled.

For, there was Bitzer, out of breath, his thin lips parted, his thin nostrils distended, his white eyelashes quivering, his colourless face more colourless than ever, as if he ran himself into a white heat, when other people ran themselves into a glow. There he stood, panting and heaving, as if he had never stopped since the night, now long ago, when he had run them down before.

‘I’m sorry to interfere with your plans,’ said Bitzer, shaking his head, ‘but I can’t allow myself to be done by horse-riders. I must have young Mr. Tom; he mustn’t be got away by horse-riders; here he is in a smock frock, and I must have him!’

By the collar, too, it seemed. For, so he took possession of him.

CHAPTER VIII

PHILOSOPHICAL

They went back into the booth, Sleary shutting the door to keep intruders out. Bitzer, still holding the paralysed culprit by the collar, stood in the Ring, blinking at his old patron through the darkness of the twilight.

‘Bitzer,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, broken down, and miserably submissive to him, ‘have you a heart?’

‘The circulation, sir,’ returned Bitzer, smiling at the oddity of the question, ‘couldn’t be carried on without one. No man, sir, acquainted with the facts established by Harvey relating to the circulation of the blood, can doubt that I have a heart.’

‘Is it accessible,’ cried Mr. Gradgrind, ‘to any compassionate influence?’

‘It is accessible to Reason, sir,’ returned the excellent young man. ‘And to nothing else.’

They stood looking at each other; Mr. Gradgrind’s face as white as the pursuer’s.

‘What motive—even what motive in reason—can you have for preventing the escape of this wretched youth,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, ‘and crushing his miserable father? See his sister here. Pity us!’

‘Sir,’ returned Bitzer, in a very business-like and logical manner, ‘since you ask me what motive I have in reason, for taking young Mr. Tom back to Coketown, it is only reasonable to let you know. I have suspected young Mr. Tom of this bank-robbery from the first. I had had my eye upon him before that time, for I knew his ways. I have kept my observations to myself, but I have made them; and I have got ample proofs against him now, besides his running away, and besides his own confession, which I was just in time to overhear. I had the pleasure of watching your house yesterday morning, and following you here. I am going to take young Mr. Tom back to Coketown, in order to deliver him over to Mr. Bounderby. Sir, I have no doubt whatever that Mr. Bounderby will then promote me to young Mr. Tom’s situation. And I wish to have his situation, sir, for it will be a rise to me, and will do me good.’

‘If this is solely a question of self-interest with you—’ Mr. Gradgrind began.

‘I beg your pardon for interrupting you, sir,’ returned Bitzer; ‘but I am sure you know that the whole social system is a question of self-interest. What you must always appeal to, is a person’s self-interest. It’s your only hold. We are so constituted. I was brought up in that catechism when I was very young, sir, as you are aware.’

‘What sum of money,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, ‘will you set against your expected promotion?’

‘Thank you, sir,’ returned Bitzer, ‘for hinting at the proposal; but I will not set any sum against it. Knowing that your clear head would propose that alternative, I have gone over the calculations in my mind; and I find that to compound a felony, even on very high terms indeed, would not be as safe and good for me as my improved prospects in the Bank.’

‘Bitzer,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, stretching out his hands as though he would have said, See how miserable I am! ‘Bitzer, I have but one chance left to soften you. You were many years at my school. If, in remembrance of the pains bestowed upon you there, you can persuade yourself in any degree to disregard your present interest and release my son, I entreat and pray you to give him the benefit of that remembrance.’

‘I really wonder, sir,’ rejoined the old pupil in an argumentative manner, ‘to find you taking a position so untenable. My schooling was paid for; it was a bargain; and when I came away, the bargain ended.’

It was a fundamental principle of the Gradgrind philosophy that everything was to be paid for. Nobody was ever on any account to give anybody anything, or render anybody help without purchase. Gratitude was to be abolished, and the virtues springing from it were not to be. Every inch of the existence of mankind, from birth to death, was to be a bargain across a counter. And if we didn’t get to Heaven that way, it was not a politico-economical place, and we had no business there.

‘I don’t deny,’ added Bitzer, ‘that my schooling was cheap. But that comes right, sir. I was made in the cheapest market, and have to dispose of myself in the dearest.’

He was a little troubled here, by Louisa and Sissy crying.

‘Pray don’t do that,’ said he, ‘it’s of no use doing that: it only worries. You seem to think that I have some animosity against young Mr. Tom; whereas I have none at all. I am only going, on the reasonable grounds I have mentioned, to take him back to Coketown. If he was to resist, I should set up the cry of Stop thief! But, he won’t resist, you may depend upon it.’

Mr. Sleary, who with his mouth open and his rolling eye as immovably jammed in his head as his fixed one, had listened to these doctrines with profound attention, here stepped forward.

‘Thquire, you know perfectly well, and your daughter knowth perfectly well (better than you, becauthe I thed it to her), that I didn’t know what your thon had done, and that I didn’t want to know—I thed it wath better not, though I only thought, then, it wath thome thkylarking. However, thith young man having made it known to be a robbery of a bank, why, that’h a theriouth thing; muth too theriouth a thing for me to compound, ath thith young man hath very properly called it. Conthequently, Thquire, you muthn’t quarrel with me if I take thith young man’th thide, and thay he’th right and there’th no help for it. But I tell you what I’ll do, Thquire; I’ll drive your thon and thith young man over to the rail, and prevent expothure here. I can’t conthent to do more, but I’ll do that.’

Fresh lamentations from Louisa, and deeper affliction on Mr. Gradgrind’s part, followed this desertion of them by their last friend. But, Sissy glanced at him with great attention; nor did she in her own breast misunderstand him. As they were all going out again, he favoured her with one slight roll of his movable eye, desiring her to linger behind. As he locked the door, he said excitedly:

‘The Thquire thtood by you, Thethilia, and I’ll thtand by the Thquire. More than that: thith ith a prethiouth rathcal, and belongth to that bluthtering Cove that my people nearly pitht out o’ winder. It’ll be a dark night; I’ve got a horthe that’ll do anything but thpeak; I’ve got a pony that’ll go fifteen mile an hour with Childerth driving of him; I’ve got a dog that’ll keep a man to one plathe four-and-twenty hourth. Get a word with the young Thquire. Tell him, when he theeth our horthe begin to danthe, not to be afraid of being thpilt, but to look out for a pony-gig coming up. Tell him, when he theeth that gig clothe by, to jump down, and it’ll take him off at a rattling pathe. If my dog leth thith young man thtir a peg on foot, I give him leave to go. And if my horthe ever thtirth from that thpot where he beginth a danthing, till the morning—I don’t know him?—Tharp’th the word!’

The word was so sharp, that in ten minutes Mr. Childers, sauntering about the market-place in a pair of slippers, had his cue, and Mr. Sleary’s equipage was ready. It was a fine sight, to behold the learned dog barking round it, and Mr. Sleary instructing him, with his one practicable eye, that Bitzer was the object of his particular attentions. Soon after dark they all three got in and started; the learned dog (a formidable creature) already pinning Bitzer with his eye, and sticking close to the wheel on his side, that he might be ready for him in the event of his showing the slightest disposition to alight.

The other three sat up at the inn all night in great suspense. At eight o’clock in the morning Mr. Sleary and the dog reappeared: both in high spirits.

‘All right, Thquire!’ said Mr. Sleary, ‘your thon may be aboard-a-thip by thith time. Childerth took him off, an hour and a half after we left there latht night. The horthe danthed the polka till he wath dead beat (he would have walthed if he hadn’t been in harneth), and then I gave him the word and he went to thleep comfortable. When that prethiouth young Rathcal thed he’d go for’ard afoot, the dog hung on to hith neck-hankercher with all four legth in the air and pulled him down and rolled him over. Tho he come back into the drag, and there he that, ’till I turned the horthe’th head, at half-patht thixth thith morning.’

Mr. Gradgrind overwhelmed him with thanks, of course; and hinted as delicately as he could, at a handsome remuneration in money.

‘I don’t want money mythelf, Thquire; but Childerth ith a family man, and if you wath to like to offer him a five-pound note, it mightn’t be unactheptable. Likewithe if you wath to thtand a collar for the dog, or a thet of bellth for the horthe, I thould be very glad to take ’em. Brandy and water I alwayth take.’ He had already called for a glass, and now called for another. ‘If you wouldn’t think it going too far, Thquire, to make a little thpread for the company at about three and thixth ahead, not reckoning Luth, it would make ’em happy.’

All these little tokens of his gratitude, Mr. Gradgrind very willingly undertook to render. Though he thought them far too slight, he said, for such a service.

‘Very well, Thquire; then, if you’ll only give a Horthe-riding, a bethpeak, whenever you can, you’ll more than balanthe the account. Now, Thquire, if your daughter will ethcuthe me, I thould like one parting word with you.’

Louisa and Sissy withdrew into an adjoining room; Mr. Sleary, stirring and drinking his brandy and water as he stood, went on:

‘Thquire,—you don’t need to be told that dogth ith wonderful animalth.’

‘Their instinct,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, ‘is surprising.’

‘Whatever you call it—and I’m bletht if I know what to call it’—said Sleary, ‘it ith athtonithing. The way in whith a dog’ll find you—the dithtanthe he’ll come!’

‘His scent,’ said Mr. Gradgrind, ‘being so fine.’

‘I’m bletht if I know what to call it,’ repeated Sleary, shaking his head, ‘but I have had dogth find me, Thquire, in a way that made me think whether that dog hadn’t gone to another dog, and thed, “You don’t happen to know a perthon of the name of Thleary, do you? Perthon of the name of Thleary, in the Horthe-Riding way—thtout man—game eye?” And whether that dog mightn’t have thed, “Well, I can’t thay I know him mythelf, but I know a dog that I think would be likely to be acquainted with him.” And whether that dog mightn’t have thought it over, and thed, “Thleary, Thleary! O yeth, to be thure! A friend of mine menthioned him to me at one time. I can get you hith addreth directly.” In conthequenth of my being afore the public, and going about tho muth, you thee, there mutht be a number of dogth acquainted with me, Thquire, that I don’t know!’

Mr. Gradgrind seemed to be quite confounded by this speculation.

‘Any way,’ said Sleary, after putting his lips to his brandy and water, ‘ith fourteen month ago, Thquire, thinthe we wath at Chethter. We wath getting up our Children in the Wood one morning, when there cometh into our Ring, by the thtage door, a dog. He had travelled a long way, he wath in a very bad condithon, he wath lame, and pretty well blind. He went round to our children, one after another, as if he wath a theeking for a child he know’d; and then he come to me, and throwd hithelf up behind, and thtood on hith two forelegth, weak ath he wath, and then he wagged hith tail and died. Thquire, that dog wath Merrylegth.’

‘Sissy’s father’s dog!’

‘Thethilia’th father’th old dog. Now, Thquire, I can take my oath, from my knowledge of that dog, that that man wath dead—and buried—afore that dog come back to me. Joth’phine and Childerth and me talked it over a long time, whether I thould write or not. But we agreed, “No. There’th nothing comfortable to tell; why unthettle her mind, and make her unhappy?” Tho, whether her father bathely detherted her; or whether he broke hith own heart alone, rather than pull her down along with him; never will be known, now, Thquire, till—no, not till we know how the dogth findth uth out!’

‘She keeps the bottle that he sent her for, to this hour; and she will believe in his affection to the last moment of her life,’ said Mr. Gradgrind.

‘It theemth to prethent two thingth to a perthon, don’t it, Thquire?’ said Mr. Sleary, musing as he looked down into the depths of his brandy and water: ‘one, that there ith a love in the world, not all Thelf-interetht after all, but thomething very different; t’other, that it hath a way of ith own of calculating or not calculating, whith thomehow or another ith at leatht ath hard to give a name to, ath the wayth of the dogth ith!’

Mr. Gradgrind looked out of window, and made no reply. Mr. Sleary emptied his glass and recalled the ladies.

‘Thethilia my dear, kith me and good-bye! Mith Thquire, to thee you treating of her like a thithter, and a thithter that you trutht and honour with all your heart and more, ith a very pretty thight to me. I hope your brother may live to be better detherving of you, and a greater comfort to you. Thquire, thake handth, firtht and latht! Don’t be croth with uth poor vagabondth. People mutht be amuthed. They can’t be alwayth a learning, nor yet they can’t be alwayth a working, they an’t made for it. You mutht have uth, Thquire. Do the withe thing and the kind thing too, and make the betht of uth; not the wurtht!’

‘And I never thought before,’ said Mr. Sleary, putting his head in at the door again to say it, ‘that I wath tho muth of a Cackler!’

CHAPTER IX

FINAL

It is a dangerous thing to see anything in the sphere of a vain blusterer, before the vain blusterer sees it himself. Mr. Bounderby felt that Mrs. Sparsit had audaciously anticipated him, and presumed to be wiser than he. Inappeasably indignant with her for her triumphant discovery of Mrs. Pegler, he turned this presumption, on the part of a woman in her dependent position, over and over in his mind, until it accumulated with turning like a great snowball. At last he made the discovery that to discharge this highly connected female—to have it in his power to say, ‘She was a woman of family, and wanted to stick to me, but I wouldn’t have it, and got rid of her’—would be to get the utmost possible amount of crowning glory out of the connection, and at the same time to punish Mrs. Sparsit according to her deserts.

Filled fuller than ever, with this great idea, Mr. Bounderby came in to lunch, and sat himself down in the dining-room of former days, where his portrait was. Mrs. Sparsit sat by the fire, with her foot in her cotton stirrup, little thinking whither she was posting.

Since the Pegler affair, this gentlewoman had covered her pity for Mr. Bounderby with a veil of quiet melancholy and contrition. In virtue thereof, it had become her habit to assume a woful look, which woful look she now bestowed upon her patron.

‘What’s the matter now, ma’am?’ said Mr. Bounderby, in a very short, rough way.

‘Pray, sir,’ returned Mrs. Sparsit, ‘do not bite my nose off.’

‘Bite your nose off, ma’am?’ repeated Mr. Bounderby. ‘Your nose!’ meaning, as Mrs. Sparsit conceived, that it was too developed a nose for the purpose. After which offensive implication, he cut himself a crust of bread, and threw the knife down with a noise.

Mrs. Sparsit took her foot out of her stirrup, and said, ‘Mr. Bounderby, sir!’

‘Well, ma’am?’ retorted Mr. Bounderby. ‘What are you staring at?’

‘May I ask, sir,’ said Mrs. Sparsit, ‘have you been ruffled this morning?’

‘Yes, ma’am.’

‘May I inquire, sir,’ pursued the injured woman, ‘whether I am the unfortunate cause of your having lost your temper?’

‘Now, I’ll tell you what, ma’am,’ said Bounderby, ‘I am not come here to be bullied. A female may be highly connected, but she can’t be permitted to bother and badger a man in my position, and I am not going to put up with it.’ (Mr. Bounderby felt it necessary to get on: foreseeing that if he allowed of details, he would be beaten.)

Mrs. Sparsit first elevated, then knitted, her Coriolanian eyebrows; gathered up her work into its proper basket; and rose.

‘Sir,’ said she, majestically. ‘It is apparent to me that I am in your way at present. I will retire to my own apartment.’

‘Allow me to open the door, ma’am.’

‘Thank you, sir; I can do it for myself.’

‘You had better allow me, ma’am,’ said Bounderby, passing her, and getting his hand upon the lock; ‘because I can take the opportunity of saying a word to you, before you go. Mrs. Sparsit, ma’am, I rather think you are cramped here, do you know? It appears to me, that, under my humble roof, there’s hardly opening enough for a lady of your genius in other people’s affairs.’

Mrs. Sparsit gave him a look of the darkest scorn, and said with great politeness, ‘Really, sir?’

‘I have been thinking it over, you see, since the late affairs have happened, ma’am,’ said Bounderby; ‘and it appears to my poor judgment—’

‘Oh! Pray, sir,’ Mrs. Sparsit interposed, with sprightly cheerfulness, ‘don’t disparage your judgment. Everybody knows how unerring Mr. Bounderby’s judgment is. Everybody has had proofs of it. It must be the theme of general conversation. Disparage anything in yourself but your judgment, sir,’ said Mrs. Sparsit, laughing.

Mr. Bounderby, very red and uncomfortable, resumed:

‘It appears to me, ma’am, I say, that a different sort of establishment altogether would bring out a lady of your powers. Such an establishment as your relation, Lady Scadgers’s, now. Don’t you think you might find some affairs there, ma’am, to interfere with?’

‘It never occurred to me before, sir,’ returned Mrs. Sparsit; ‘but now you mention it, should think it highly probable.’

‘Then suppose you try, ma’am,’ said Bounderby, laying an envelope with a cheque in it in her little basket. ‘You can take your own time for going, ma’am; but perhaps in the meanwhile, it will be more agreeable to a lady of your powers of mind, to eat her meals by herself, and not to be intruded upon. I really ought to apologise to you—being only Josiah Bounderby of Coketown—for having stood in your light so long.’

‘Pray don’t name it, sir,’ returned Mrs. Sparsit. ‘If that portrait could speak, sir—but it has the advantage over the original of not possessing the power of committing itself and disgusting others,—it would testify, that a long period has elapsed since I first habitually addressed it as the picture of a Noodle. Nothing that a Noodle does, can awaken surprise or indignation; the proceedings of a Noodle can only inspire contempt.’

Thus saying, Mrs. Sparsit, with her Roman features like a medal struck to commemorate her scorn of Mr. Bounderby, surveyed him fixedly from head to foot, swept disdainfully past him, and ascended the staircase. Mr. Bounderby closed the door, and stood before the fire; projecting himself after his old explosive manner into his portrait—and into futurity.