Sex Interest And Sex Behavior

Sex Interest and Sex Behavior: To master the important developmental tasks of forming new and more mature relationships with members of the opposite sex and of playing the approved role for one’s sex, the young adolescent must acquire more complete and more mature concepts of sex than he had as a child. The motivation to do so comes partly from his interest in sex. With the development of the sexual capacities at the time of puberty comes a change in the form of interest that adolescents take in members of the opposite sex. No longer are boys and girls primarily interested in physical differences, although this interest never completely vanishes. The new interest that develops during the early part of adolescence is romantic in nature. This is accompanied by a strong desire to win the approval of members of the opposite sex. Knowledge about sex is acquired as a result of the curiosity the individual has about sex. This curiosity, which became pronounced at puberty, provided the individual has been able to get the information he wishes to satisfy his curiosity. There is still, however, a lively interest in sex, though this is not likely to preoccupy the time and interest of young adolescents as much as it did earlier, during the puberty period.

Pattern of Sex Interests: Interest in members of the opposite sex heterosexuality – follows a predictable pattern, with variations in ages at which the adolescent reaches different stages in this pattern partly because of differences in age of sexual maturing and partly because of differences in opportunities to develop this interest. Interest in members of the opposite sex is also markedly influenced by patterns of interest among the adolescent’s friends. Studies of large groups of adolescents have shown what the predictable pattern of heterosexuality is. In the transition from aversion toward members of the opposite sex, characteristic of puberty, to falling in love with members of the opposite sex, it is quite usual for both boys and girls to center their affections first on a member of their own sex, older than they, who has qualities they admire, and then, later, on a member of the opposite sex who is distinctly older then they. When the attachment is for a person whom the adolescent knows and has personal contacts with, it is usually called a “crush”, when the attachment is for a person not known personally but admired from afar, it is generally referred to as “here worshiping”. However, this distinction is worshiping”. However, this distinction is not always made, and the latter attachment is then also called a “crush”. The object of the adolescent’s crush is a person who embodies the qualities the adolescent admires. This person becomes the focal point of the adolescent’s admiration and love. Whether it is a teacher, a camp counselor, a sports star, an actor or actress, a crooner, or even an older relative or friend of the family, there is a strong desire on the adolescent’s part to imitate this individual. If the object of affection is a person known to the adolescent, there is added to the desire to imitate a strong desire to be with the loved person, to do everything possible to win the favor and attention of that person, and to be constantly thinking and talking about the loved one. Crushes and hero-worshiping generally reach their peak around fourteen years of age, after which there is a rapid decline in interest in these love objects. There is no evidence that crushes are a barrier to later heterosexual adjustments. On the other hand, there is evidence that crushes may prove to be a healthy learning experience for the young adolescent. As Rybak has explained, “The main function of the adult in the crush or hero-worship relationship is to help the young person to learn from this experience and then to gradually grow away from it into a more mature relationship”.

Approved Sex Roles:

Even more difficult than learning to get along with age-mates of the opposite sex is the developmental task of learning to play the approved sex roles for one’s sex. For boys, this is not nearly so difficult as it is for girls. The reasons for this are, first, since earliest childhood boys have been told what is the approved behavior for boys and have been encouraged, prodded, or even shamed into conforming to the approved standards, and, second, boys, discover with each passing year that the male female role. Girls, by contrast, reach adolescence with blurred of what the female role is, though their concepts of the male role are clearer and better defined. This is because, as children, they were permitted to look, act, and feel much as boys without constant prodding’s to be “feminine”. Even when they learn what society expects of girls, their motivation to mold their behavior in accordance with the standards outlined in the concept of the traditional female role is week because they realize that this role is far less prestigious than the male role and even less prestigious than the role they played as children. Many young adolescent girls rebel against the “double standard” of behavior on the grounds that the pattern of their lives has been on an equalitarian basis with boys and that they should not be expected to learn a new pattern now, especially when this pattern is less to their liking that the childhood pattern. However, they soon discover that rebellion against accepting the traditional female role is punished by social rejection, not only by members of the opposite sex, but also by members of their own sex. Before early adolescence is over, most girls accept, often reluctantly, the stereotype of the female role as a model for their own behavior and pretend that they are “feminine” even though they prefer an equalitarian role that combines features of both the male and the female roles. This is a price they are willing to pay, temporarily at least, for the social acceptance they crave. In spite of the fact that most girls, as they approach the end of adolescence, maintain that their preference for their adult role is that of wife and mother, they often find it difficult to accept their appropriate sex role. Not only is there ambiguity about what the appropriate sex role is for the woman of today, but also the girl discovers, early in her teens, that boys consider the female role subordinate to that of the male. In one study in which male college students were questioned about the role of the female students, it was found that the male students felt that the female students should take courses in preparation for the domestic role and they felt that, since woman’s place is in the home, school and college work should be a preparation for this role.

Differentiation in Relationship:

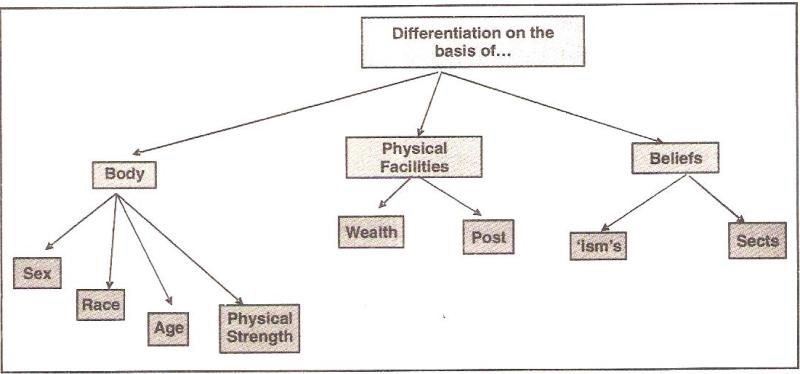

Respect means accepting individuality and doing right evaluation (to be evaluated as I am). Our basis for respect today is largely quite contrary to our discussion above. Instead of respect being a basis of similarity or one of right evaluation, we have made it into something on the basis of which we differentiate i.e. by respecting you mean you are doing something special, because you are special or have something special or are in some special position. Thus, all of us are running around seeking respect from one another by trying to become something special. Today, we are differentiating in the name of respect. We either differentiate people on the basis of their body, on the basis of their wealth and possessions or on the basis of their beliefs. There is no notion of respect in terms of right evaluation. Thus, there is no real feeling of relationship, only one of differentiation.