CHAPTER IV—A ROSE IN MISERY

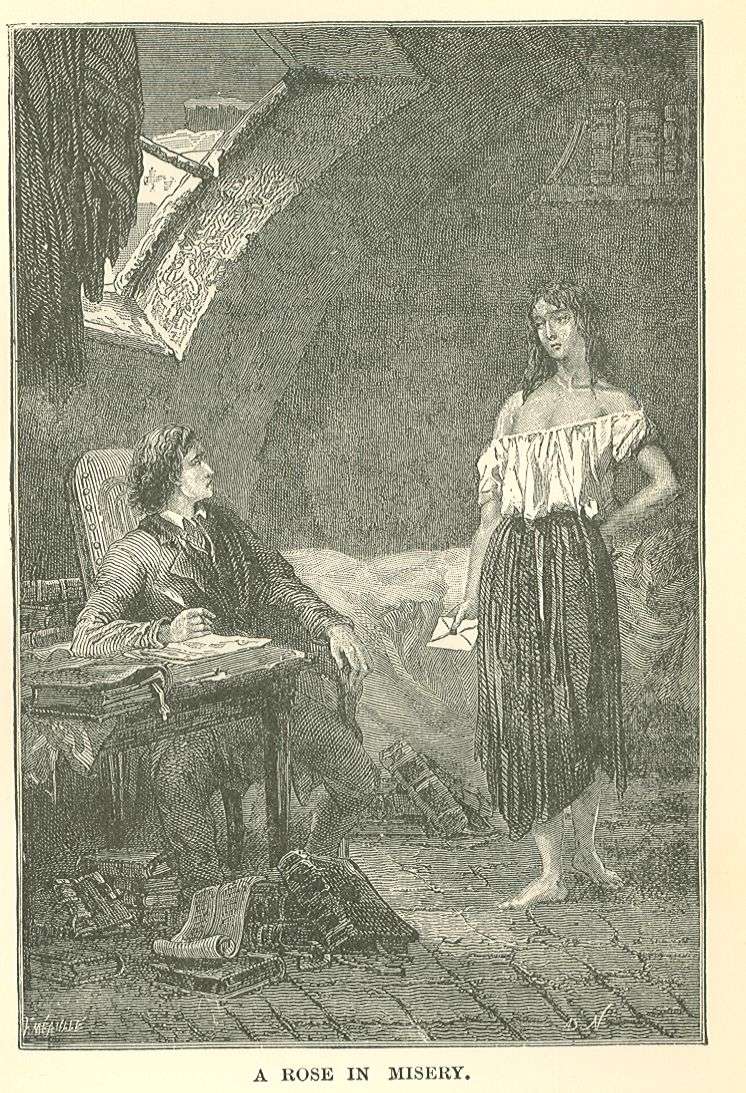

A very young girl was standing in the half-open door. The dormer window of the garret, through which the light fell, was precisely opposite the door, and illuminated the figure with a wan light. She was a frail, emaciated, slender creature; there was nothing but a chemise and a petticoat upon that chilled and shivering nakedness. Her girdle was a string, her head ribbon a string, her pointed shoulders emerged from her chemise, a blond and lymphatic pallor, earth-colored collar-bones, red hands, a half-open and degraded mouth, missing teeth, dull, bold, base eyes; she had the form of a young girl who has missed her youth, and the look of a corrupt old woman; fifty years mingled with fifteen; one of those beings which are both feeble and horrible, and which cause those to shudder whom they do not cause to weep.

Marius had risen, and was staring in a sort of stupor at this being, who was almost like the forms of the shadows which traverse dreams.

The most heart-breaking thing of all was, that this young girl had not come into the world to be homely. In her early childhood she must even have been pretty. The grace of her age was still struggling against the hideous, premature decrepitude of debauchery and poverty. The remains of beauty were dying away in that face of sixteen, like the pale sunlight which is extinguished under hideous clouds at dawn on a winter’s day.

That face was not wholly unknown to Marius. He thought he remembered having seen it somewhere.

“What do you wish, Mademoiselle?” he asked.

The young girl replied in her voice of a drunken convict:—

“Here is a letter for you, Monsieur Marius.”

She called Marius by his name; he could not doubt that he was the person whom she wanted; but who was this girl? How did she know his name?

Without waiting for him to tell her to advance, she entered. She entered resolutely, staring, with a sort of assurance that made the heart bleed, at the whole room and the unmade bed. Her feet were bare. Large holes in her petticoat permitted glimpses of her long legs and her thin knees. She was shivering.

She held a letter in her hand, which she presented to Marius.

Marius, as he opened the letter, noticed that the enormous wafer which sealed it was still moist. The message could not have come from a distance. He read:—

MY AMIABLE NEIGHBOR,

YOUNG MAN: I have learned of your goodness to me,

that you paid my rent six months ago. I bless you, young man. My eldest

daughter will tell you that we have been without a morsel of bread for two

days, four persons and my spouse ill. If I am not deseaved in my opinion, I

think I may hope that your generous heart will melt at this statement and the

desire will subjugate you to be propitious to me by daigning to lavish on me a

slight favor.

I am with the distinguished consideration which is due to the

benefactors of humanity,—

JONDRETTE.

P.S. My eldest daughter will await your orders, dear Monsieur Marius.

This letter, coming in the very midst of the mysterious adventure which had occupied Marius’ thoughts ever since the preceding evening, was like a candle in a cellar. All was suddenly illuminated.

This letter came from the same place as the other four. There was the same writing, the same style, the same orthography, the same paper, the same odor of tobacco.

There were five missives, five histories, five signatures, and a single signer. The Spanish Captain Don Alvarès, the unhappy Mistress Balizard, the dramatic poet Genflot, the old comedian Fabantou, were all four named Jondrette, if, indeed, Jondrette himself were named Jondrette.

Marius had lived in the house for a tolerably long time, and he had had, as we have said, but very rare occasion to see, to even catch a glimpse of, his extremely mean neighbors. His mind was elsewhere, and where the mind is, there the eyes are also. He had been obliged more than once to pass the Jondrettes in the corridor or on the stairs; but they were mere forms to him; he had paid so little heed to them, that, on the preceding evening, he had jostled the Jondrette girls on the boulevard, without recognizing them, for it had evidently been they, and it was with great difficulty that the one who had just entered his room had awakened in him, in spite of disgust and pity, a vague recollection of having met her elsewhere.

Now he saw everything clearly. He understood that his neighbor Jondrette, in his distress, exercised the industry of speculating on the charity of benevolent persons, that he procured addresses, and that he wrote under feigned names to people whom he judged to be wealthy and compassionate, letters which his daughters delivered at their risk and peril, for this father had come to such a pass, that he risked his daughters; he was playing a game with fate, and he used them as the stake. Marius understood that probably, judging from their flight on the evening before, from their breathless condition, from their terror and from the words of slang which he had overheard, these unfortunate creatures were plying some inexplicably sad profession, and that the result of the whole was, in the midst of human society, as it is now constituted, two miserable beings who were neither girls nor women, a species of impure and innocent monsters produced by misery.

Sad creatures, without name, or sex, or age, to whom neither good nor evil were any longer possible, and who, on emerging from childhood, have already nothing in this world, neither liberty, nor virtue, nor responsibility. Souls which blossomed out yesterday, and are faded to-day, like those flowers let fall in the streets, which are soiled with every sort of mire, while waiting for some wheel to crush them. Nevertheless, while Marius bent a pained and astonished gaze on her, the young girl was wandering back and forth in the garret with the audacity of a spectre. She kicked about, without troubling herself as to her nakedness. Occasionally her chemise, which was untied and torn, fell almost to her waist. She moved the chairs about, she disarranged the toilet articles which stood on the commode, she handled Marius’ clothes, she rummaged about to see what there was in the corners.

“Hullo!” said she, “you have a mirror!”

And she hummed scraps of vaudevilles, as though she had been alone, frolicsome refrains which her hoarse and guttural voice rendered lugubrious.

An indescribable constraint, weariness, and humiliation were perceptible beneath this hardihood. Effrontery is a disgrace.

Nothing could be more melancholy than to see her sport about the room, and, so to speak, flit with the movements of a bird which is frightened by the daylight, or which has broken its wing. One felt that under other conditions of education and destiny, the gay and over-free mien of this young girl might have turned out sweet and charming. Never, even among animals, does the creature born to be a dove change into an osprey. That is only to be seen among men.

Marius reflected, and allowed her to have her way.

She approached the table.

“Ah!” said she, “books!”

A flash pierced her glassy eye. She resumed, and her accent expressed the happiness which she felt in boasting of something, to which no human creature is insensible:—

“I know how to read, I do!”

She eagerly seized a book which lay open on the table, and read with tolerable fluency:—

“—General Bauduin received orders to take the château of Hougomont which stands in the middle of the plain of Waterloo, with five battalions of his brigade.”

She paused.

“Ah! Waterloo! I know about that. It was a battle long ago. My father was there. My father has served in the armies. We are fine Bonapartists in our house, that we are! Waterloo was against the English.”

She laid down the book, caught up a pen, and exclaimed:—

“And I know how to write, too!”

She dipped her pen in the ink, and turning to Marius:—

“Do you want to see? Look here, I’m going to write a word to show you.”

And before he had time to answer, she wrote on a sheet of white paper, which lay in the middle of the table: “The bobbies are here.”

Then throwing down the pen:—

“There are no faults of orthography. You can look. We have received an education, my sister and I. We have not always been as we are now. We were not made—”

Here she paused, fixed her dull eyes on Marius, and burst out laughing, saying, with an intonation which contained every form of anguish, stifled by every form of cynicism:—

“Bah!”

And she began to hum these words to a gay air:—

“J’ai faim, mon père.”

Pas de fricot.

J’ai froid, ma mère.

Pas de tricot.

Grelotte,

Lolotte!

Sanglote,

Jacquot!”

I am hungry, father.

I have no food.

I am cold, mother.

I have no clothes.

Lolotte!

Shiver,

Sob,

Jacquot!”

She had hardly finished this couplet, when she exclaimed:—

“Do you ever go to the play, Monsieur Marius? I do. I have a little brother who is a friend of the artists, and who gives me tickets sometimes. But I don’t like the benches in the galleries. One is cramped and uncomfortable there. There are rough people there sometimes; and people who smell bad.”

Then she scrutinized Marius, assumed a singular air and said:—

“Do you know, Mr. Marius, that you are a very handsome fellow?”

And at the same moment the same idea occurred to them both, and made her smile and him blush. She stepped up to him, and laid her hand on his shoulder: “You pay no heed to me, but I know you, Mr. Marius. I meet you here on the staircase, and then I often see you going to a person named Father Mabeuf who lives in the direction of Austerlitz, sometimes when I have been strolling in that quarter. It is very becoming to you to have your hair tumbled thus.”

She tried to render her voice soft, but only succeeded in making it very deep. A portion of her words was lost in the transit from her larynx to her lips, as though on a piano where some notes are missing.

Marius had retreated gently.

“Mademoiselle,” said he, with his cool gravity, “I have here a package which belongs to you, I think. Permit me to return it to you.”

And he held out the envelope containing the four letters.

She clapped her hands and exclaimed:—

“We have been looking everywhere for that!”

Then she eagerly seized the package and opened the envelope, saying as she did so:—

“Dieu de Dieu! how my sister and I have hunted! And it was you who found it! On the boulevard, was it not? It must have been on the boulevard? You see, we let it fall when we were running. It was that brat of a sister of mine who was so stupid. When we got home, we could not find it anywhere. As we did not wish to be beaten, as that is useless, as that is entirely useless, as that is absolutely useless, we said that we had carried the letters to the proper persons, and that they had said to us: ‘Nix.’ So here they are, those poor letters! And how did you find out that they belonged to me? Ah! yes, the writing. So it was you that we jostled as we passed last night. We couldn’t see. I said to my sister: ‘Is it a gentleman?’ My sister said to me: ‘I think it is a gentleman.’”

In the meanwhile she had unfolded the petition addressed to “the benevolent gentleman of the church of Saint-Jacques-du-Haut-Pas.”

“Here!” said she, “this is for that old fellow who goes to mass. By the way, this is his hour. I’ll go and carry it to him. Perhaps he will give us something to breakfast on.”

Then she began to laugh again, and added:—

“Do you know what it will mean if we get a breakfast today? It will mean that we shall have had our breakfast of the day before yesterday, our breakfast of yesterday, our dinner of to-day, and all that at once, and this morning. Come! Parbleu! if you are not satisfied, dogs, burst!”

This reminded Marius of the wretched girl’s errand to himself. He fumbled in his waistcoat pocket, and found nothing there.

The young girl went on, and seemed to have no consciousness of Marius’ presence.

“I often go off in the evening. Sometimes I don’t come home again. Last winter, before we came here, we lived under the arches of the bridges. We huddled together to keep from freezing. My little sister cried. How melancholy the water is! When I thought of drowning myself, I said to myself: ‘No, it’s too cold.’ I go out alone, whenever I choose, I sometimes sleep in the ditches. Do you know, at night, when I walk along the boulevard, I see the trees like forks, I see houses, all black and as big as Notre Dame, I fancy that the white walls are the river, I say to myself: ‘Why, there’s water there!’ The stars are like the lamps in illuminations, one would say that they smoked and that the wind blew them out, I am bewildered, as though horses were breathing in my ears; although it is night, I hear hand-organs and spinning-machines, and I don’t know what all. I think people are flinging stones at me, I flee without knowing whither, everything whirls and whirls. You feel very queer when you have had no food.”

And then she stared at him with a bewildered air.

By dint of searching and ransacking his pockets, Marius had finally collected five francs sixteen sous. This was all he owned in the world for the moment. “At all events,” he thought, “there is my dinner for to-day, and to-morrow we will see.” He kept the sixteen sous, and handed the five francs to the young girl.

She seized the coin.

“Good!” said she, “the sun is shining!”

And, as though the sun had possessed the property of melting the avalanches of slang in her brain, she went on:—

“Five francs! the shiner! a monarch! in this hole! Ain’t this fine! You’re a jolly thief! I’m your humble servant! Bravo for the good fellows! Two days’ wine! and meat! and stew! we’ll have a royal feast! and a good fill!”

She pulled her chemise up on her shoulders, made a low bow to Marius, then a familiar sign with her hand, and went towards the door, saying:—

“Good morning, sir. It’s all right. I’ll go and find my old man.”

As she passed, she caught sight of a dry crust of bread on the commode, which was moulding there amid the dust; she flung herself upon it and bit into it, muttering:—

“That’s good! it’s hard! it breaks my teeth!”

Then she departed.