CHAPTER V—FACTS WHENCE HISTORY SPRINGS AND WHICH HISTORY IGNORES

Towards the end of April, everything had become aggravated. The fermentation entered the boiling state. Ever since 1830, petty partial revolts had been going on here and there, which were quickly suppressed, but ever bursting forth afresh, the sign of a vast underlying conflagration. Something terrible was in preparation. Glimpses could be caught of the features still indistinct and imperfectly lighted, of a possible revolution. France kept an eye on Paris; Paris kept an eye on the Faubourg Saint-Antoine.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine, which was in a dull glow, was beginning its ebullition.

The wine-shops of the Rue de Charonne were, although the union of the two epithets seems singular when applied to wine-shops, grave and stormy.

The government was there purely and simply called in question. There people publicly discussed the question of fighting or of keeping quiet. There were back shops where workingmen were made to swear that they would hasten into the street at the first cry of alarm, and “that they would fight without counting the number of the enemy.” This engagement once entered into, a man seated in the corner of the wine-shop “assumed a sonorous tone,” and said, “You understand! You have sworn!”

Sometimes they went upstairs, to a private room on the first floor, and there scenes that were almost masonic were enacted. They made the initiated take oaths to render service to himself as well as to the fathers of families. That was the formula.

In the tap-rooms, “subversive” pamphlets were read. They treated the government with contempt, says a secret report of that time.

Words like the following could be heard there:—

“I don’t know the names of the leaders. We folks shall not know the day until two hours beforehand.” One workman said: “There are three hundred of us, let each contribute ten sous, that will make one hundred and fifty francs with which to procure powder and shot.”

Another said: “I don’t ask for six months, I don’t ask for even two. In less than a fortnight we shall be parallel with the government. With twenty-five thousand men we can face them.” Another said: “I don’t sleep at night, because I make cartridges all night.” From time to time, men “of bourgeois appearance, and in good coats” came and “caused embarrassment,” and with the air of “command,” shook hands with the most important, and then went away. They never stayed more than ten minutes. Significant remarks were exchanged in a low tone: “The plot is ripe, the matter is arranged.” “It was murmured by all who were there,” to borrow the very expression of one of those who were present. The exaltation was such that one day, a workingman exclaimed, before the whole wine-shop: “We have no arms!” One of his comrades replied: “The soldiers have!” thus parodying without being aware of the fact, Bonaparte’s proclamation to the army in Italy: “When they had anything of a more secret nature on hand,” adds one report, “they did not communicate it to each other.” It is not easy to understand what they could conceal after what they said.

These reunions were sometimes periodical. At certain ones of them, there were never more than eight or ten persons present, and they were always the same. In others, any one entered who wished, and the room was so full that they were forced to stand. Some went thither through enthusiasm and passion; others because it was on their way to their work. As during the Revolution, there were patriotic women in some of these wine-shops who embraced newcomers.

Other expressive facts came to light.

A man would enter a shop, drink, and go his way with the remark: “Wine-merchant, the revolution will pay what is due to you.”

Revolutionary agents were appointed in a wine-shop facing the Rue de Charonne. The balloting was carried on in their caps.

Workingmen met at the house of a fencing-master who gave lessons in the Rue de Cotte. There there was a trophy of arms formed of wooden broadswords, canes, clubs, and foils. One day, the buttons were removed from the foils.

A workman said: “There are twenty-five of us, but they don’t count on me, because I am looked upon as a machine.” Later on, that machine became Quenisset.

The indefinite things which were brewing gradually acquired a strange and indescribable notoriety. A woman sweeping off her doorsteps said to another woman: “For a long time, there has been a strong force busy making cartridges.” In the open street, proclamation could be seen addressed to the National Guard in the departments. One of these proclamations was signed: Burtot, wine-merchant.

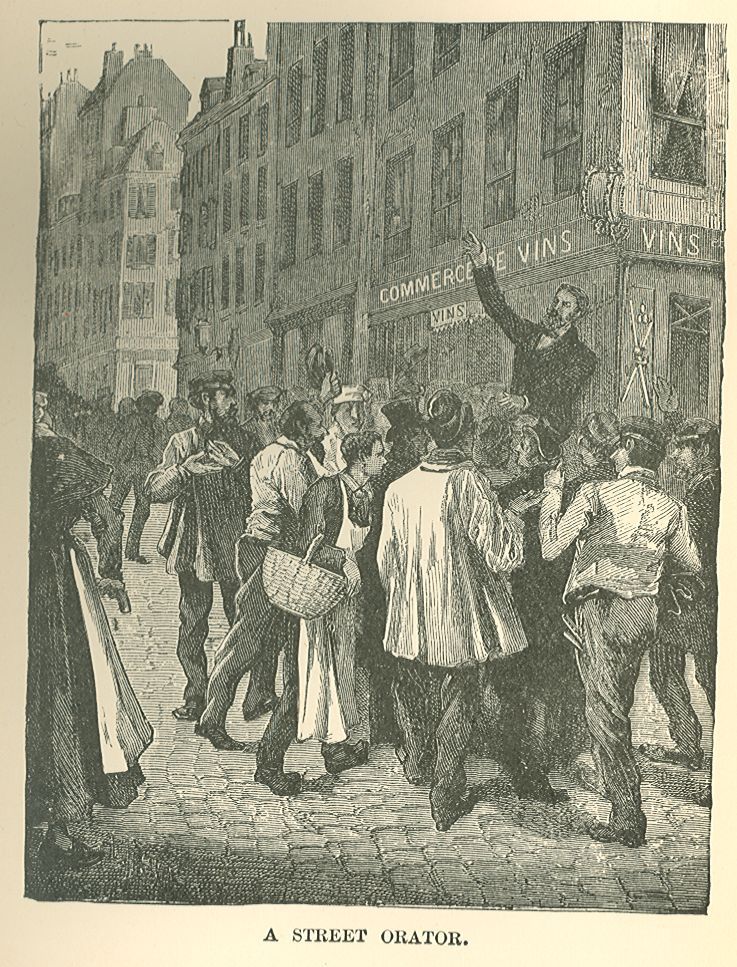

One day a man with his beard worn like a collar and with an Italian accent mounted a stone post at the door of a liquor-seller in the Marché Lenoir, and read aloud a singular document, which seemed to emanate from an occult power. Groups formed around him, and applauded.

The passages which touched the crowd most deeply were collected and noted down. “—Our doctrines are trammelled, our proclamations torn, our bill-stickers are spied upon and thrown into prison.”—“The breakdown which has recently taken place in cottons has converted to us many mediums.”—“The future of nations is being worked out in our obscure ranks.”—“Here are the fixed terms: action or reaction, revolution or counter-revolution. For, at our epoch, we no longer believe either in inertia or in immobility. For the people against the people, that is the question. There is no other.”—“On the day when we cease to suit you, break us, but up to that day, help us to march on.” All this in broad daylight.

Other deeds, more audacious still, were suspicious in the eyes of the people by reason of their very audacity. On the 4th of April, 1832, a passer-by mounted the post on the corner which forms the angle of the Rue Sainte-Marguerite and shouted: “I am a Babouvist!” But beneath Babeuf, the people scented Gisquet.

Among other things, this man said:—

“Down with property! The opposition of the left is cowardly and treacherous. When it wants to be on the right side, it preaches revolution, it is democratic in order to escape being beaten, and royalist so that it may not have to fight. The republicans are beasts with feathers. Distrust the republicans, citizens of the laboring classes.”

“Silence, citizen spy!” cried an artisan.

This shout put an end to the discourse.

Mysterious incidents occurred.

At nightfall, a workingman encountered near the canal a “very well dressed man,” who said to him: “Whither are you bound, citizen?” “Sir,” replied the workingman, “I have not the honor of your acquaintance.” “I know you very well, however.” And the man added: “Don’t be alarmed, I am an agent of the committee. You are suspected of not being quite faithful. You know that if you reveal anything, there is an eye fixed on you.” Then he shook hands with the workingman and went away, saying: “We shall meet again soon.”

The police, who were on the alert, collected singular dialogues, not only in the wine-shops, but in the street.

“Get yourself received very soon,” said a weaver to a cabinet-maker.

“Why?”

“There is going to be a shot to fire.”

Two ragged pedestrians exchanged these remarkable replies, fraught with evident Jacquerie:—

“Who governs us?”

“M. Philippe.”

“No, it is the bourgeoisie.”

The reader is mistaken if he thinks that we take the word Jacquerie in a bad sense. The Jacques were the poor.

On another occasion two men were heard to say to each other as they passed by: “We have a good plan of attack.”

Only the following was caught of a private conversation between four men who were crouching in a ditch of the circle of the Barrière du Trône:—

“Everything possible will be done to prevent his walking about Paris any more.”

Who was the he? Menacing obscurity.

“The principal leaders,” as they said in the faubourg, held themselves apart. It was supposed that they met for consultation in a wine-shop near the point Saint-Eustache. A certain Aug—, chief of the Society aid for tailors, Rue Mondétour, had the reputation of serving as intermediary central between the leaders and the Faubourg Saint-Antoine.

Nevertheless, there was always a great deal of mystery about these leaders, and no certain fact can invalidate the singular arrogance of this reply made later on by a man accused before the Court of Peers:—

“Who was your leader?”

“I knew of none and I recognized none.”

There was nothing but words, transparent but vague; sometimes idle reports, rumors, hearsay. Other indications cropped up.

A carpenter, occupied in nailing boards to a fence around the ground on which a house was in process of construction, in the Rue de Reuilly found on that plot the torn fragment of a letter on which were still legible the following lines:—

The committee must take measures to prevent recruiting in the sections for the different societies.

And, as a postscript:—

We have learned that there are guns in the Rue du Faubourg-Poissonnière, No. 5 [bis], to the number of five or six thousand, in the house of a gunsmith in that court. The section owns no arms.

What excited the carpenter and caused him to show this thing to his neighbors was the fact, that a few paces further on he picked up another paper, torn like the first, and still more significant, of which we reproduce a facsimile, because of the historical interest attaching to these strange documents:—

![[Illustration: Q C D E Learn this list by heart. After so doing you will tear it up. The men admitted will do the same when you have transmitted their orders to them. Health and Fraternity, u og a’ fe L.]](https://bridge.skedbooks.com/contents/sb135/OEBPS/3536207615303723747_4b1-5-a-page26.jpg)

Q C D E

Learn this list by heart. After so doing you will tear it up. The men

admitted will do the same when you have transmitted their orders to them.

Health and Fraternity,

u og a’ fe

L.

It was only later on that the persons who were in the secret of this find at the time, learned the significance of those four capital letters: quinturions, centurions, decurions, éclaireurs [scouts], and the sense of the letters: u og a’ fe, which was a date, and meant April 15th, 1832. Under each capital letter were inscribed names followed by very characteristic notes. Thus: Q. Bannerel. 8 guns, 83 cartridges. A safe man.—C. Boubière. 1 pistol, 40 cartridges.—D. Rollet. 1 foil, 1 pistol, 1 pound of powder.—E. Tessier. 1 sword, 1 cartridge-box. Exact.— Terreur. 8 guns. Brave, etc.

Finally, this carpenter found, still in the same enclosure, a third paper on which was written in pencil, but very legibly, this sort of enigmatical list:—

Unité: Blanchard: Arbre-Sec. 6.

Barra. Soize. Salle-au-Comte.

Kosciusko. Aubry the Butcher?

J. J. R.

Caius Gracchus.

Right of revision. Dufond. Four.

Fall of the Girondists. Derbac. Maubuée.

Washington. Pinson. 1 pistol, 86 cartridges.

Marseillaise.

Sovereignty of the people. Michel. Quincampoix. Sword.

Hoche.

Marceau. Plato. Arbre-Sec.

Warsaw. Tilly, crier of the Populaire.

The honest bourgeois into whose hands this list fell knew its significance. It appears that this list was the complete nomenclature of the sections of the fourth arondissement of the Society of the Rights of Man, with the names and dwellings of the chiefs of sections. To-day, when all these facts which were obscure are nothing more than history, we may publish them. It should be added, that the foundation of the Society of the Rights of Man seems to have been posterior to the date when this paper was found. Perhaps this was only a rough draft.

Still, according to all the remarks and the words, according to written notes, material facts begin to make their appearance.

In the Rue Popincourt, in the house of a dealer in bric-à-brac, there were seized seven sheets of gray paper, all folded alike lengthwise and in four; these sheets enclosed twenty-six squares of this same gray paper folded in the form of a cartridge, and a card, on which was written the following:—

Saltpetre . . . . . . . . . . . 12 ounces.

Sulphur . . . . . . . . . . . 2 ounces.

Charcoal . . . . . . . . . . . 2 ounces and a half.

Water . . . . . . . . . . . 2 ounces.

The report of the seizure stated that the drawer exhaled a strong smell of powder.

A mason returning from his day’s work, left behind him a little package on a bench near the bridge of Austerlitz. This package was taken to the police station. It was opened, and in it were found two printed dialogues, signed Lahautière, a song entitled: “Workmen, band together,” and a tin box full of cartridges.

One artisan drinking with a comrade made the latter feel him to see how warm he was; the other man felt a pistol under his waistcoat.

In a ditch on the boulevard, between Père-Lachaise and the Barrière du Trône, at the most deserted spot, some children, while playing, discovered beneath a mass of shavings and refuse bits of wood, a bag containing a bullet-mould, a wooden punch for the preparation of cartridges, a wooden bowl, in which there were grains of hunting-powder, and a little cast-iron pot whose interior presented evident traces of melted lead.

Police agents, making their way suddenly and unexpectedly at five o’clock in the morning, into the dwelling of a certain Pardon, who was afterwards a member of the Barricade-Merry section and got himself killed in the insurrection of April, 1834, found him standing near his bed, and holding in his hand some cartridges which he was in the act of preparing.

Towards the hour when workingmen repose, two men were seen to meet between the Barrière Picpus and the Barrière Charenton in a little lane between two walls, near a wine-shop, in front of which there was a “Jeu de Siam.”33 One drew a pistol from beneath his blouse and handed it to the other. As he was handing it to him, he noticed that the perspiration of his chest had made the powder damp. He primed the pistol and added more powder to what was already in the pan. Then the two men parted.

A certain Gallais, afterwards killed in the Rue Beaubourg in the affair of April, boasted of having in his house seven hundred cartridges and twenty-four flints.

The government one day received a warning that arms and two hundred thousand cartridges had just been distributed in the faubourg. On the following week thirty thousand cartridges were distributed. The remarkable point about it was, that the police were not able to seize a single one.

An intercepted letter read: “The day is not far distant when, within four hours by the clock, eighty thousand patriots will be under arms.”

All this fermentation was public, one might almost say tranquil. The approaching insurrection was preparing its storm calmly in the face of the government. No singularity was lacking to this still subterranean crisis, which was already perceptible. The bourgeois talked peaceably to the working-classes of what was in preparation. They said: “How is the rising coming along?” in the same tone in which they would have said: “How is your wife?”

A furniture-dealer, of the Rue Moreau, inquired: “Well, when are you going to make the attack?”

Another shop-keeper said:—

“The attack will be made soon.”

“I know it. A month ago, there were fifteen thousand of you, now there are twenty-five thousand.” He offered his gun, and a neighbor offered a small pistol which he was willing to sell for seven francs.

Moreover, the revolutionary fever was growing. Not a point in Paris nor in France was exempt from it. The artery was beating everywhere. Like those membranes which arise from certain inflammations and form in the human body, the network of secret societies began to spread all over the country. From the associations of the Friends of the People, which was at the same time public and secret, sprang the Society of the Rights of Man, which also dated from one of the orders of the day: Pluviôse, Year 40 of the republican era, which was destined to survive even the mandate of the Court of Assizes which pronounced its dissolution, and which did not hesitate to bestow on its sections significant names like the following:—

Pikes.

Tocsin.

Signal cannon.

Phrygian cap.

January 21.

The beggars.

The vagabonds.

Forward march.

Robespierre.

Level.

Ça Ira.

The Society of the Rights of Man engendered the Society of Action. These were impatient individuals who broke away and hastened ahead. Other associations sought to recruit themselves from the great mother societies. The members of sections complained that they were torn asunder. Thus, the Gallic Society, and the committee of organization of the Municipalities. Thus the associations for the liberty of the press, for individual liberty, for the instruction of the people against indirect taxes. Then the Society of Equal Workingmen which was divided into three fractions, the levellers, the communists, the reformers. Then the Army of the Bastilles, a sort of cohort organized on a military footing, four men commanded by a corporal, ten by a sergeant, twenty by a sub-lieutenant, forty by a lieutenant; there were never more than five men who knew each other. Creation where precaution is combined with audacity and which seemed stamped with the genius of Venice.

The central committee, which was at the head, had two arms, the Society of Action, and the Army of the Bastilles.

A legitimist association, the Chevaliers of Fidelity, stirred about among these the republican affiliations. It was denounced and repudiated there.

The Parisian societies had ramifications in the principal cities, Lyons, Nantes, Lille, Marseilles, and each had its Society of the Rights of Man, the Charbonnière, and The Free Men. All had a revolutionary society which was called the Cougourde. We have already mentioned this word.

In Paris, the Faubourg Saint-Marceau kept up an equal buzzing with the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, and the schools were no less moved than the faubourgs. A café in the Rue Saint-Hyacinthe and the wine-shop of the Seven Billiards, Rue des Mathurins-Saint-Jacques, served as rallying points for the students. The Society of the Friends of the A B C affiliated to the Mutualists of Angers, and to the Cougourde of Aix, met, as we have seen, in the Café Musain. These same young men assembled also, as we have stated already, in a restaurant wine-shop of the Rue Mondétour which was called Corinthe. These meetings were secret. Others were as public as possible, and the reader can judge of their boldness from these fragments of an interrogatory undergone in one of the ulterior prosecutions: “Where was this meeting held?” “In the Rue de la Paix.” “At whose house?” “In the street.” “What sections were there?” “Only one.” “Which?” “The Manuel section.” “Who was its leader?” “I.” “You are too young to have decided alone upon the bold course of attacking the government. Where did your instructions come from?” “From the central committee.”

The army was mined at the same time as the population, as was proved subsequently by the operations of Béford, Luneville, and Épinard. They counted on the fifty-second regiment, on the fifth, on the eighth, on the thirty-seventh, and on the twentieth light cavalry. In Burgundy and in the southern towns they planted the liberty tree; that is to say, a pole surmounted by a red cap.

Such was the situation.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine, more than any other group of the population, as we stated in the beginning, accentuated this situation and made it felt. That was the sore point. This old faubourg, peopled like an ant-hill, laborious, courageous, and angry as a hive of bees, was quivering with expectation and with the desire for a tumult. Everything was in a state of agitation there, without any interruption, however, of the regular work. It is impossible to convey an idea of this lively yet sombre physiognomy. In this faubourg exists poignant distress hidden under attic roofs; there also exist rare and ardent minds. It is particularly in the matter of distress and intelligence that it is dangerous to have extremes meet.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine had also other causes to tremble; for it received the counter-shock of commercial crises, of failures, strikes, slack seasons, all inherent to great political disturbances. In times of revolution misery is both cause and effect. The blow which it deals rebounds upon it. This population full of proud virtue, capable to the highest degree of latent heat, always ready to fly to arms, prompt to explode, irritated, deep, undermined, seemed to be only awaiting the fall of a spark. Whenever certain sparks float on the horizon chased by the wind of events, it is impossible not to think of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and of the formidable chance which has placed at the very gates of Paris that powder-house of suffering and ideas.

The wine-shops of the Faubourg Antoine, which have been more than once drawn in the sketches which the reader has just perused, possess historical notoriety. In troublous times people grow intoxicated there more on words than on wine. A sort of prophetic spirit and an afflatus of the future circulates there, swelling hearts and enlarging souls. The cabarets of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine resemble those taverns of Mont Aventine erected on the cave of the Sibyl and communicating with the profound and sacred breath; taverns where the tables were almost tripods, and where was drunk what Ennius calls the sibylline wine.

The Faubourg Saint-Antoine is a reservoir of people. Revolutionary agitations create fissures there, through which trickles the popular sovereignty. This sovereignty may do evil; it can be mistaken like any other; but, even when led astray, it remains great. We may say of it as of the blind cyclops, Ingens.

In ’93, according as the idea which was floating about was good or evil, according as it was the day of fanaticism or of enthusiasm, there leaped forth from the Faubourg Saint-Antoine now savage legions, now heroic bands.

Savage. Let us explain this word. When these bristling men, who in the early days of the revolutionary chaos, tattered, howling, wild, with uplifted bludgeon, pike on high, hurled themselves upon ancient Paris in an uproar, what did they want? They wanted an end to oppression, an end to tyranny, an end to the sword, work for men, instruction for the child, social sweetness for the woman, liberty, equality, fraternity, bread for all, the idea for all, the Edenizing of the world. Progress; and that holy, sweet, and good thing, progress, they claimed in terrible wise, driven to extremities as they were, half naked, club in fist, a roar in their mouths. They were savages, yes; but the savages of civilization.

They proclaimed right furiously; they were desirous, if only with fear and trembling, to force the human race to paradise. They seemed barbarians, and they were saviours. They demanded light with the mask of night.

Facing these men, who were ferocious, we admit, and terrifying, but ferocious and terrifying for good ends, there are other men, smiling, embroidered, gilded, beribboned, starred, in silk stockings, in white plumes, in yellow gloves, in varnished shoes, who, with their elbows on a velvet table, beside a marble chimney-piece, insist gently on demeanor and the preservation of the past, of the Middle Ages, of divine right, of fanaticism, of innocence, of slavery, of the death penalty, of war, glorifying in low tones and with politeness, the sword, the stake, and the scaffold. For our part, if we were forced to make a choice between the barbarians of civilization and the civilized men of barbarism, we should choose the barbarians.

But, thank Heaven, still another choice is possible. No perpendicular fall is necessary, in front any more than in the rear.

Neither despotism nor terrorism. We desire progress with a gentle slope.

God takes care of that. God’s whole policy consists in rendering slopes less steep.