The copy of Morga’s History in the British Museum used by Rizal.

Besides the copying of the text of Morga’s history, Rizal read many other early writings on the Philippines, and the manifest unfairness of some of these who thought that they could glorify Spain only by disparaging the Filipinos aroused his wrath. Few Spanish writers held up the good name of those who were under their flag, and Rizal had to resort to foreign authorities to disprove their libels. Morga was almost alone among Spanish historians, Page 151Page 152but his assertions found corroboration in the contemporary chronicles of other nationalities. Rizal spent his evenings in the home of Doctor Regidor, and many a time the bitterness and impatience with which his day’s work in the Museum had inspired him, would be forgotten as the older man counseled patience and urged that such prejudices were to be expected of a little educated nation. Then Rizal’s brow would clear as he quoted his favorite proverb, “To understand all is to forgive all.”

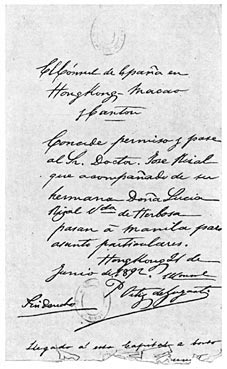

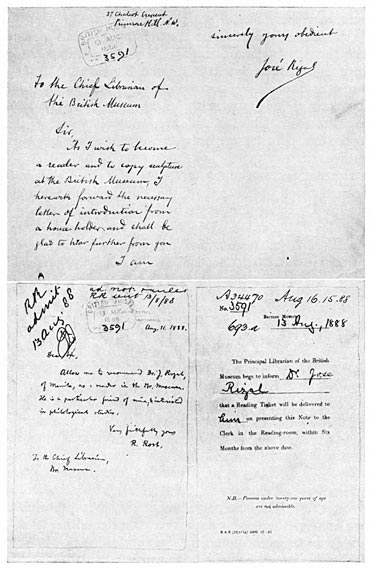

Application, recommendation, and admission of Rizal to the reading-room of the British Museum.

Doctor Rost was editor of Trübner’s Record, a journal devoted to the literature of the East, founded by the famous Oriental Bookseller and Publisher of London, Nicholas Trübner, and Doctor Rizal contributed to it in May, 1889, some specimens of Tagal folklore, an extract from which is appended, as it was then printed:

Specimens of Tagal Folklore

Proverbial Sayings

Malakas ang bulong sa sigaw, Low words are stronger than loud words.

Ang lakí sa layaw karaniwa ’y hubad, A petted child is generally naked (i.e. poor).

Hampasng magulang ay nakatabã, Parents’ punishment makes one fat.

Ibang harī ibang ugaīl, New king, new fashion.

Nagpupútol ang kapus, ang labis ay nagdurugtong, What is short cuts off a piece from itself, what is long adds another on (the poor gets poorer, the rich richer).

Ang nagsasabing tapus ay siyang kinakapus, He who finishes his words finds himself wanting.

Nangangakõ habang napapakõ, Man promises while in need.

Page 153Ang naglalakad ng maráhan, matinik may mababaw, He who walks slowly, though he may put his foot on a thorn, will not be hurt very much (Tagals mostly go barefooted).

Ang maniwalã sa sabi ’y walang bait na sarili, He who believes in tales has no own mind.

Ang may isinuksok sa dingding, ay may titingalain, He who has put something between the wall may afterwards look on (the saving man may afterwards be cheerful).—The wall of a Tagal house is made of palm-leaves and bamboo, so that it can be used as a cupboard.

Walang mahirap gisingin na paris nang nagtutulogtulugan, The most difficult to rouse from sleep is the man who pretends to be asleep.

Labis sa salitã, kapus sa gawã, Too many words, too little work.

Hipong tulog ay nadadalá ng ánod, The sleeping shrimp is carried away by the current.

Sa bibig nahuhuli ang isda, The fish is caught through the mouth.

Puzzles

Isang butil na palay sikip sa buony bahay, One rice-corn fills up all the house.—The light. The rice-corn with the husk is yellowish.

Matapang akó so dalawá, duag akó sa isá, I am brave against two, coward against one.—The bamboo bridge. When the bridge is made of one bamboo only, it is difficult to pass over; but when it is made of two or more, it is very easy.

Dalá akó niya, dalá ko siya, He carries me, I carry him.—The shoes.

Isang balong malalim puna ng patalím, A deep well filled with steel blades.—The mouth.

Page 154The Filipino colony in Spain had established a fortnightly review, published first in Barcelona and later in Madrid, to enlighten Spaniards on their distant colony, and Rizal wrote for it from the start. Its name, La Solidaridad, perhaps may be translated Equal Rights, as it aimed at like laws and the same privileges for the Peninsula and the possessions overseas.

Heading of the Filipino-Madrid review “La Solidaridad.”

From the Philippines came news of a contemptible attempt to reach Rizal through his family—one of many similar petty persecutions. His sister Lucia’s husband had died and the corpse was refused interment in consecrated ground, upon the pretext that the dead man, who had been exceptionally liberal to the church and was of unimpeachable character, had been negligent in his religious duties. Another individual with a notorious record of longer absence from confession died about the same time, and his funeral took place from the church without demur. The ugly feature about the refusal to bury Hervosa was that the telegram from the friar parish-priest to the Archbishop at Manila in asking instructions, was careful to mention that the deceased was a brother-in-law of Rizal. Doctor Rizal wrote a scorching article for La Solidaridad under the caption “An Outrage,” and Page 155took the matter up with the Spanish Colonial Minister, then Becerra, a professed Liberal. But that weakling statesman, more liberal in words than in actions, did nothing.

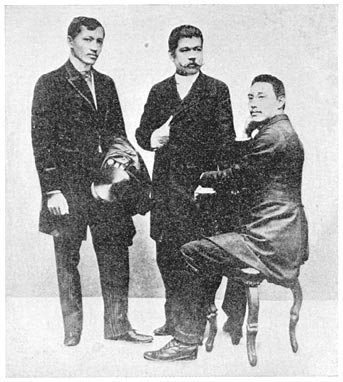

Staff of “La Solidaridad.” José Rizal, Marcelo H. de Pilar, Mariano Ponce.

That the union of Church and State can be as demoralizing to religion as it is disastrous to good government seems sufficiently established by Philippine incidents like this, in which politics was substituted for piety as the test of a good Catholic, making marriage impossible and denying decent burial to the families of those who differed politically with the ministers of the national religion.

Page 156Of all his writings, the article in which Rizal speaks of this indignity to the dead comes nearest to exhibiting personal feeling and rancor. Yet his main point is to indicate generally what monstrous conditions the Philippine mixture of religion and politics made possible.

The following are part of a series of nineteen verses published in La Solidaridad over Rizal’s favorite pen name of Laong Laan:

To my Muse

(translation by Charles Derbyshire)

Invoked no longer is the Muse,

The lyre is out of date;

The poets it no longer use,

And youth its inspiration now imbues

With other form and state.

If today our fancies aught

Of verse would still require,

Helicon’s hill remains unsought;

And without heed we but inquire,

Why the coffee is not brought.

In the place of thought sincere

That our hearts may feel,

We must seize a pen of steel,

And with verse and line severe

Fling abroad a jest and jeer.

Muse, that in the past inspired me,

And with songs of love hast fired me;

Go thou now to dull repose,

For today in sordid prose

I must earn the gold that hired me.

Now must I ponder deep,

Meditate, and struggle on;

E’en sometimes I must weep;

For he who love would keep

Great pain has undergone.

Fled are the days of ease,

The days of Love’s delight;

When flowers still would please

And give to suffering souls surcease

From pain and sorrow’s blight.

One by one they have passed on,

All I loved and moved among;

Dead or married—from me gone,

For all I place my heart upon

By fate adverse are stung.

Go thou, too, O Muse, depart,

Other regions fairer find;

For my land but offers art

For the laurel, chains that bind,

For a temple, prisons blind.

But before thou leavest me, speak:

Tell me with thy voice sublime,

Thou couldst ever from me seek

A song of sorrow for the weak,

Defiance to the tyrant’s crime.

Rizal’s congenial situation in the British capital was disturbed by his discovering a growing interest in the youngest of the three girls whom he daily met. He felt that his career did not permit him to marry, nor was his youthful affection for his cousin in Manila an entirely Page 158forgotten sentiment. Besides, though he never lapsed into such disregard for his feminine friends as the low Spanish standard had made too common among the Filipino students in Madrid, Rizal was ever on his guard against himself. So he suggested to Doctor Regidor that he considered it would be better for him to leave London. His parting gift to the family with whom he had lived so happily was a clay medallion bearing in relief the profiles of the three sisters.

Other regretful good-bys were said to a number of young Filipinos whom he had gathered around him and formed into a club for the study of the history of their country and the discussion of its politics.

Rizal now went to Paris, where he was glad to be again with his friend Valentin Ventura, a wealthy Pampangan who had been trained for the law. His tastes and ideals were very much those of Rizal, and he had sound sense and a freedom from affectation which especially appealed to Rizal. There Rizal’s reprint of Morga’s rare history was made, at a greater cost but also in better form than his first novel. Copious notes gave references to other authorities and compared present with past conditions, and Doctor Blumentritt contributed a forceful introduction.

When Rizal returned to London to correct the proofsheets, the old original book was in use and the copy could not be checked. This led to a number of errors, misspelled and changed words, and even omissions of sentences, which were afterwards discovered and carefully listed and filed away to be corrected in another edition.

Possibly it has been made clear already that, while Rizal did not work for separation from Spain, he was no admirer of the Castilian character, nor of the Latin type, for that matter. He remarked on Blumentritt’s comparison of the Spanish rulers in the Philippines with the Page 159Czars of Russia, that it is flattering to the Castilians but it is more than they merit, to put them in the same class as Russia. Apparently he had in mind the somewhat similar comparison in Burke’s speech on the conciliation of America, in which he said that Russia was more advanced and less cruel than Spain and so not to be classed with it.

During his stay in Paris, Rizal was a frequent visitor at the home of the two Doctors Pardo de Tavera, sons of the exile of ’72 who had gone to France, the younger now a physician in South America, the elder a former Philippine Commissioner. The interest of the one in art, and of the other in philology, the ideas of progress through education shared by both, and many other common tastes and ideals, made the two young men fast friends of Rizal. Mrs. Tavera, the mother, was an interesting conversationalist, and Rizal profited by her reminiscences of Philippine official life, to the inner circle of which her husband’s position had given her the entrée.

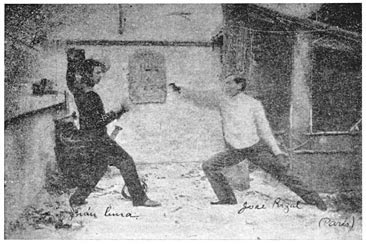

On Sundays Rizal fenced at Juan Luna’s house with his distinguished artist-countryman, or, while the latter was engaged with Ventura, watched their play. It was on one of these afternoons that the Tagalog story of “The Monkey and the Tortoise”1 was hastily sketched as a joke to fill the remaining pages of Mrs. Luna’s autograph album, in which she had been insisting Rizal must write before all its space was used up. A comparison of the Tagalog version with a Japanese counterpart was published by Rizal in English, in Trübner’s Magazine, suggesting that the two people may have had a common origin. This study received considerable attention from other ethnologists, and was among the topics at an ethnological conference.

At times his antagonist was Miss Nellie Baustead, who had great skill with the foils. Her father, himself born Page 160in the Philippines, the son of a wealthy merchant of Singapore, had married a member of the Genato family of Manila. At their villa in Biarritz, and again in their home in Belgium, Rizal was a guest later, for Mr. Baustead had taken a great liking to him.

Rizal fencing with Luna in Paris.

The teaching instinct that led him to act as mentor to the Filipino students in Spain and made him the inspiration of a mutual improvement club of his young countrymen in London, suggested the foundation of a school in Paris. Later a Pampangan youth offered him $40,000 with which to found a Filipino college in Hongkong, where many young men from the Philippines had obtained an education better than their own land could afford but not entirely adapted to their needs. The scheme attracted Rizal, and a prospectus for such an institution which was later found among his papers not only proves how deeply he was interested, but reveals the fact that his ideas of education were essentially like those Page 161carried out in the present public-school course of instruction in the Philippines.

|

General Weyler, known as “Butcher Weyler.” |

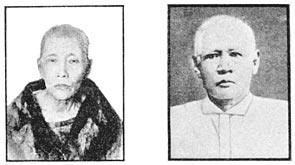

Early in August of 1890 Rizal went to Madrid to seek redress for a wrong done his family by the notorious General Weyler, the “Butcher” of evil memory in Cuba, then Governor-General of the Philippines. Just as the mother’s loss of liberty, years before, was caused by revengeful feelings on the part of an official because for one day she was obliged to omit a customary gift of horse feed, so the father’s loss of land was caused by a revengeful official, and for quite as trivial a cause.

Mr. Mercado was a great poultry fancier and especially prided himself upon his fine stock of turkeys. He had been accustomed to respond to the frequent requests of the estate agent for presents of birds. But at one time disease had so reduced the number of turkeys that all that remained were needed for breeding purposes and Mercado was obliged to refuse him. In a rage the agent insisted, and when that proved unavailing, threats followed.

Page 162But Francisco Mercado was not a man to be moved by threats, and when the next rent day came round he was notified that his rent had been doubled. This was paid without protest, for the tenants were entirely at the mercy of the landlords, no fixed rate appearing either in contracts or receipts. Then the rent-raising was kept on till Mercado was driven to seek the protection of the courts. Part of his case led to exactly the same situation as that of the Biñan tenantry in his grandfather’s time, when the landlords were compelled to produce their title-deeds, and these proved that land of others had been illegally included in the estate. Other tenants, emboldened by Mercado’s example also refused to pay the exorbitant rent increases.

Rizal’s parents during the land troubles.

The justice of the peace of Kalamba, before whom the case first came, was threatened by the provincial governor for taking time to hear the testimony, and the case was turned over to the auxiliary justice, who promptly decided in the manner desired by the authorities. Mercado at once took an appeal, but the venal Weyler moved a force of artillery to Kalamba and quartered it upon the town as if rebellion openly existed there. Then the court representatives evicted the people from their homes and Page 163directed them to remove all their buildings from the estate lands within twenty-four hours. In answer to the plea that they had appealed to the Supreme Court the tenants were told their houses could be brought back again if they Page 164won their appeal. Of course this was impossible and some 150,000 pesos’ worth of property was consequently destroyed by the court agents, who were worthy estate employees. Twenty or more families were made homeless and the other tenants were forbidden to shelter them under pain of their own eviction. This is the proceeding in which Retana suggests that the governor-general and the landlords were legally within their rights. If so, Spanish law was a disgrace to the nation. Fortunately the Rizal-Mercado family had another piece of property at Los Baños, and there they made their home.

The Writ of eviction against Rizal’s father. (Facsimile.)

Weyler’s motives in this matter do not have to be surmised, for among the (formerly) secret records of the government there exists a letter which he wrote when he first denied the petition of the Kalamba residents. It is marked “confidential” and is addressed to the landlords, expressing the pleasure which this action gave him. Then the official adds that it cannot have escaped their notice that the times demand diplomacy in handling the situation but that, should occasion arise, he will act with energy. Just as Weyler had favored the landlords at first so he kept on and when he had a chance to do something for them he did it.

Finally, when Weyler left the Islands an investigation was ordered into his administration, owing to rumors of extensive and systematic frauds on the government, but nothing more came of the case than that Retana, later Rizal’s biographer, wrote a book in the General’s defense, “extensively documented,” and also abusively anti-Filipino. It has been urged (not by Retana, however) that the Weyler régime was unusually efficient, because he would allow no one but himself to make profits out of the public, and therefore, while his gains were greater than those of his predecessors, the Islands really received more attention from him.

Page 165During the Kalamba discussion in Spain, Retana, until 1899 always scurrilously anti-Filipino, made the mistake of his life, for he charged Rizal’s family with not paying their rent, which was not true. While Rizal believed that duelling was murder, to judge from a pair of pictures preserved in his album, he evidently considered that homicide of one like Retana was justifiable. After the Spanish custom, his seconds immediately called upon the author of the libel. Retana notes in his “Vida del Dr. Rizal” that the incident closed in a way honorable to both Rizal and himself—he, Retana, published an explicit retraction and abject apology in the Madrid papers. Another time, in Madrid, Rizal risked a duel when he challenged Antonio Luna, later the General, because of a slighting allusion to a lady at a public banquet. He had a nicer sense of honor in such matters than prevailed in Madrid, and Luna promptly saw the matter from Rizal’s point of view and withdrew the offensive remark. This second incident complements the first, for it shows that Rizal was as willing to risk a duel with his superior in arms as with one not so skilled as he. Rizal was an exceptional pistol shot and a fair swordsman, while Retana was inferior with either sword or pistol, but Luna, who would have had the choice of weapons, was immeasurably Rizal’s superior with the sword.

Owing to a schism a rival arose against the old Masonry and finally the original organization succumbed to the offshoot. Doctor Miguel Morayta, Professor of History in the Central University at Madrid, was the head of the new institution and it had grown to be very popular among students. Doctor Morayta was friendly to the Filipinos and a lodge of the same name as their paper was organized among them. For their outside work they had a society named the Hispano-Filipino Association, of which Morayta was president, with convenient clubrooms Page 166and a membership practically the same as the Lodge La Solidaridad.

Just before Christmas of 1890, this Hispano-Filipino Association gave a largely attended banquet at which there were many prominent speakers. Rizal stayed away, not because of growing pessimism, as Retana suggests, but because one of the speakers was the same Becerra who had feared to act when the outrage against the body of Rizal’s brother-in-law had been reported to him. Now out of office, the ex-minister was again bold in words, but Rizal for one was not again to be deceived by them.

The propaganda carried on by his countrymen in the Peninsula did not seem to Rizal effective, and he found his suggestions were not well received by those at its head. The story of Rizal’s separation from La Solidaridad, however, is really not material, but the following quotation from a letter written to Carlos Oliver, speaking of the opposition of the Madrid committee of Filipinos to himself, is interesting as showing Rizal’s attitude of mind:

“I regret exceedingly that they war against me, attempting to discredit me in the Philippines, but I shall be content provided only that my successor keeps on with the work. I ask only of those who say that I created discord among the Filipinos: Was there any effective union before I entered political life? Was there any chief whose authority I wanted to oppose? It is a pity that in our slavery we should have rivalries over leadership.”

And in Rizal’s letter from Hongkong, May 24, 1892, to Zulueta, commenting on an article by Leyte in La Solidaridad, he says:

“Again I repeat, I do not understand the reason of the attack, since now I have dedicated myself to preparing for our countrymen a safe refuge in case of persecution Page 167and to writing some books, championing our cause, which shortly will appear. Besides, the article is impolitic in the extreme and prejudicial to the Philippines. Why say that the first thing we need is to have money? A wiser man would be silent and not wash soiled linen in public.”

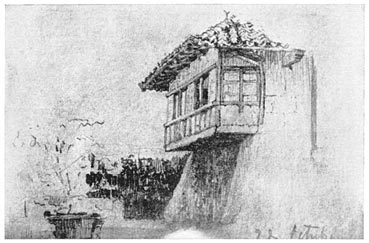

Room in which “El Filibusterismo” was begun.

(Pencil sketch by Rizal.)

Early in ’91 Rizal went to Paris, visiting Mr. Baustead’s villa in Biarritz en route, and he was again a guest of his hospitable friend when, after the winter season was over, the family returned to their home in Brussels.

During most of the year Rizal’s residence was in Ghent, where he had gathered around him a number of Filipinos. Doctor Blumentritt suggested that he should devote himself to the study of Malay-Polynesian languages, and as it appeared that thus he could earn a living in Holland he thought to make his permanent home there. But his parents were old and reluctant to leave their native land to pass their last years in a strange country, and that plan failed. Page 168

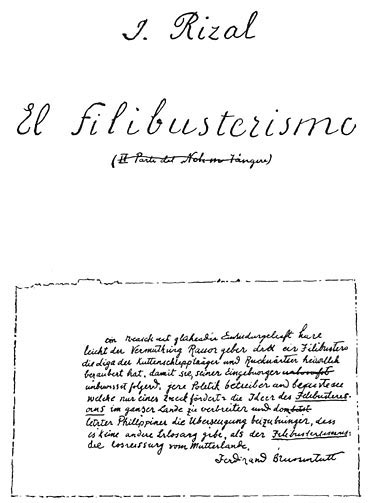

Facsimile of the first page of the MS. of “El Filibusterismo.”

(Property of Mr. Valentin Ventura, of Barcelona.)

He now occupied himself in finishing the sequel to “Noli Me Tangere,” the novel “El Filibusterismo,” which he had begun in October of 1887 while on his visit to the Philippines. The bolder painting of the evil effects Page 169of the Spanish culture upon the Filipinos may well have been inspired by his unfortunate experiences with his countrymen in Madrid who had not seen anything of Europe outside of Spain. On the other hand, the confidence of the author in those of his countrymen who had not been contaminated by the so-called Spanish civilization, is even more noticeable than in “Noli Me Tangere.”

Cover of the MS. of “El Filibusterismo.”

Rizal had now done all that he could for his country; he had shown them by Morga what they were when Spain found them; through “Noli Me Tangere” he had painted their condition after three hundred years of Spanish influence; and in “El Filibusterismo” he had pictured what their future must be if better counsels did not prevail in the colony.

These works were for the instruction of his countrymen, the fulfilment of the task he set for himself when he first read Doctor Jagor’s criticism fifteen years before; time only was now needed for them to accomplish their work and for education to bring forth its fruits. Page 170

Chapter VIII

Despujol’s Duplicity

As soon as he had set in motion what influence he possessed in Europe for the relief of his relatives, Rizal hurried to Hongkong and from there wrote to his parents asking their permission to join them. Some time before, his brother-in-law, Manuel Hidalgo, had been deported upon the recommendation of the governor of La Laguna, “to prove to the Filipinos that they were mistaken in thinking that the new Civil Code gave them any rights” in cases where the governor-general agreed with his subordinate’s reason for asking for the deportation as well as in its desirability. The offense was having buried a child, who had died of cholera, without church ceremonies. The law prescribed and public health demanded it. But the law was a dead letter and the public health was never considered when these cut into church revenues, as Hidalgo ought to have known.

Upon Rizal’s arrival in Hongkong, in the fall of 1891, he received notice that his brother Paciano had been returned from exile in Mindoro, but that three of his sisters had been summoned, with the probability of deportation.

A trap to get Rizal into the hands of the government by playing upon his affection for his mother was planned at this time, but it failed. Mrs. Rizal and one of her daughters were arrested in Manila for “falsification of cedula” because they no longer used the name Realonda, which the mother had dropped fifteen years before. Then, though there were frequently boats running to Kalamba, the two women were ordered to be taken there for trial on foot. As when Mrs. Rizal had been a prisoner before, the humane guards disobeyed their orders Page 171and the elderly lady was carried in a hammock. The family understood the plans of their persecutors, and Rizal was told by his parents not to come to Manila. Then the persecution of the mother and the sister dropped.

In Hongkong, Rizal was already acquainted with most of the Filipino colony, including Jose M. Basa, a ’72 exile of great energy, for whom he had the greatest respect. The old man was an unceasing enemy of all the religious orders and was constantly getting out “proclamations,” as the handbills common in the old-time controversies were called. One of these, against the Jesuits, figures in the case against Rizal and bears some minor corrections in his handwriting. Nevertheless, his participation in it was probably no more than this proofreading for his friend, whose motives he could appreciate, but whose plan of action was not in harmony with his own ideas.

Letters of introduction from London friends secured for Rizal the acquaintance of Mr. H. L. Dalrymple, a justice of the peace—which is a position more coveted and honored in English lands than here—and a member of the public library committee, as well as of the board of medical examiners. He was a merchant, too, and agent for the British North Borneo Company, which had recently secured a charter as a semi-independent colony for the extensive cession which had originally been made to the American Trading Company and later transferred to them.

Rizal spent much of his time in the library, reading especially the files of the older newspapers, which contained frequent mention of the Philippines. As an old-time missionary had left his books to the library, the collection was rich in writings of the fathers of the early Church, as well as in philology and travel. He spent much time also in long conversations with Editor Frazier-Smith Page 172of the Hongkong Telegraph, the most enterprising of the daily newspapers. He was the master of St. John’s Masonic lodge (Scotch constitution), which Rizal had visited upon his first arrival, intensely democratic and a close student of world politics. The two became fast friends and Rizal contributed to the Telegraph several articles on Philippine matters. These were printed in Spanish, ostensibly for the benefit of the Filipino colony in Hongkong, but large numbers of the paper were mailed to the Philippines and thus at first escaped the vigilance of the censors. Finally the scheme was discovered and the Telegraph placed on the prohibited list, but, like most Spanish actions, this was just too late to prevent the circulation of what Rizal had wished to say to his countrymen.

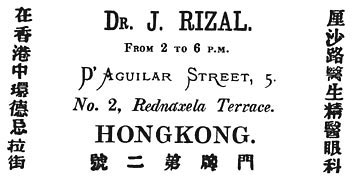

Rizal’s professional card when in Hongkong.

With the first of the year 1892 the free portion of Rizal’s family came to Hongkong. He had been licensed to practice medicine in the colony, and opened an office, specializing as an oculist with notable success.

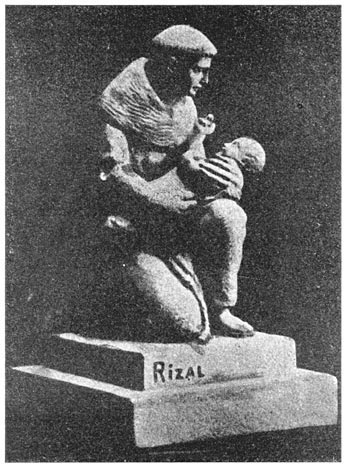

Statuette modelled by Rizal.

Another congenial companion was a man of his own profession, Doctor L. P. Marquez, a Portuguese who had received his medical education in Dublin and was a naturalized British subject. He was a leading member of Page 173the Portuguese club, Lusitania, which was of radically republican proclivities and possessed an excellent library of books on modern political conditions. An inspection of the colonial prison with him inspired Rizal’s article, “A Visit to Victoria Gaol,” through which runs a pathetic contrast of the English system of imprisonment for reformation Page 174with the Spanish vindictive methods of punishment. A souvenir of one of their many conferences was a dainty modeling in clay made by Rizal with that astonishing quickness that resulted from his Uncle Gabriel’s training during his early childhood.

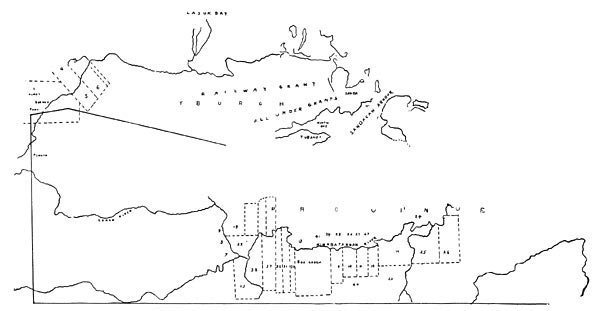

In the spring, Rizal took a voyage to British North Borneo and with Mr. Pryor, the agent, looked over vacant lands which had been offered him by the Company for a Filipino colony. The officials were anxious to grow abaca, cacao, sugar cane and coconuts, all products of the Philippines, the soil of which resembled theirs. So they welcomed the prospect of the immigration of laborers skilled in such cultivation, the Kalambans and other persecuted people of the Luzon lake region, whom Doctor Rizal hoped to transplant there to a freer home.

|

Don Eulogio Despujol. |

A different kind of governor-general had succeeded Weyler in the Philippines; the new man was Despujol, a friend of the Jesuits and a man who at once gave the Filipinos hope of better days, for his promises were quickly backed up by the beginnings of their performance. Rizal witnessed this novel experience for his country with gratification, though he had seen too many disappointments to confide in the continuance of reform, and he remembered that the like liberal term of De la Torre had ended in the Cavite reaction.

He wrote early to the new chief executive, applauding Despujol’s policy and offering such coöperation as he might be able to give toward making it a complete success. No reply had been received, but after Rizal’s return from his Borneo trip the Spanish consul in Hongkong Page 175Page 176assured him that he would not be molested should he go to Manila.

Proposed settlement in Borneo.

Rizal therefore made up his mind to visit his home once more. He still cherished the plan of transferring those of his relatives and friends who were homeless through the land troubles, or discontented with their future in the Philippines, to the district offered to him by the British North Borneo Company. There, under the protection of the British flag, but in their accustomed climate, with familiar surroundings amid their own people, a New Kalamba would be established. Filipinos would there have a chance to prove to the world what they were capable of, and their free condition would inevitably react on the neighboring Philippines and help to bring about better government there.

Rizal had no intention of renouncing his Philippine allegiance, for he always regretted the naturalization of his countrymen abroad, considering it a loss to the country which needed numbers to play the influential part he hoped it would play in awakening Asia. All his arguments were for British justice and “Equality before the Law,” for he considered that political power was only a means of securing and assuring fair treatment for all, and in itself of no interest.

With such ideas he sailed for home, bearing the Spanish consul’s passport. He left two letters in Hongkong with his friend Doctor Marquez marked, “To be opened after my death,” and their contents indicate that he was not unmindful of how little regard Spain had had in his country for her plighted honor.

One was to his beloved parents, brother and sisters, and friends:

“The affection that I have ever professed for you suggests this step, and time alone can tell whether or not it Page 177is sensible. Their outcome decides things by results, but whether that be favorable or unfavorable, it may always be said that duty urged me, so if I die in doing it, it will not matter.

“I realize how much suffering I have caused you, still I do not regret what I have done. Rather, if I had to begin over again, still I should do just the same, for it has been only duty. Gladly do I go to expose myself to peril, not as any expiation of misdeeds (for in this matter I believe myself guiltless of any), but to complete my work and myself offer the example of which I have always preached.

“A man ought to die for duty and his principles. I hold fast to every idea which I have advanced as to the condition and future of our country, and shall willingly die for it, and even more willingly to procure for you justice and peace.

“With pleasure, then, I risk life to save so many innocent persons—so many nieces and nephews, so many children of friends, and children, too, of others who are not even friends—who are suffering on my account. What am I? A single man, practically without family, and sufficiently undeceived as to life. I have had many disappointments and the future before me is gloomy, and will be gloomy if light does not illuminate it, the dawn of a better day for my native land. On the other hand, there are many individuals, filled with hope and ambition, who perhaps all might be happy were I dead, and then I hope my enemies would be satisfied and stop persecuting so many entirely innocent people. To a certain extent their hatred is justifiable as to myself, and my parents and relatives.

“Should fate go against me, you will all understand that I shall die happy in the thought that my death will Page 178end all your troubles. Return to our country and may you be happy in it.

“Till the last moment of my life I shall be thinking of you and wishing you all good fortune and happiness.”

* * * * *

The other letter was directed “To the Filipinos,” and said:

“The step which I am taking, or rather am about to take, is undoubtedly risky, and it is unnecessary to say that I have considered it some time. I understand that almost every one is opposed to it; but I know also that hardly anybody else comprehends what is in my heart. I cannot live on seeing so many suffer unjust persecutions on my account; I cannot bear longer the sight of my sisters and their numerous families treated like criminals. I prefer death and cheerfully shall relinquish life to free so many innocent persons from such unjust persecution.

“I appreciate that at present the future of our country gravitates in some degree around me, that at my death many will feel triumphant, and, in consequence, many are wishing for my fall. But what of it? I hold duties of conscience above all else, I have obligations to the families who suffer, to my aged parents whose sighs strike me to the heart; I know that I alone, only with my death, can make them happy, returning them to their native land and to a peaceful life at home. I am all my parents have, but our country has many, many more sons who can take my place and even do my work better.

“Besides I wish to show those who deny us patriotism that we know how to die for duty and principles. What matters death, if one dies for what one loves, for native land and beings held dear?

“If I thought that I were the only resource for the policy of progress in the Philippines and were I convinced that my countrymen were going to make use of my services, Page 179perhaps I should hesitate about taking this step; but there are still others who can take my place, who, too, can take my place with advantage. Furthermore, there are perchance those who hold me unneeded and my services are not utilized, resulting that I am reduced to inactivity.

“Always have I loved our unhappy land, and I am sure that I shall continue loving it till my latest moment, in case men prove unjust to me. My career, my life, my happiness, all have I sacrificed for love of it. Whatever my fate, I shall die blessing it and longing for the dawn of its redemption.”

|

Rizal’s passport, or “safe-conduct.” |

And then followed the note; “Make these letters public after my death.”

Suspicion of the Spanish authorities was justified. The consul’s cablegram notifying Governor-General Despujol. that Rizal had fallen into their trap, sent the day of issuing the “safe-conduct” or special passport, bears the same date as the secret case filed against him in Manila, “for anti religious and anti patriotic agitation.” On that same day the deceitful Despujol was confidentially inquiring of his executive secretary whether it was true Page 180that Rizal had been naturalized as a German subject, and, if so, what effect would that have on the governor-general’s right to take executive action; that is, could he deport one who had the protection of a strong nation with the same disregard for the forms of justice that he could a Filipino?