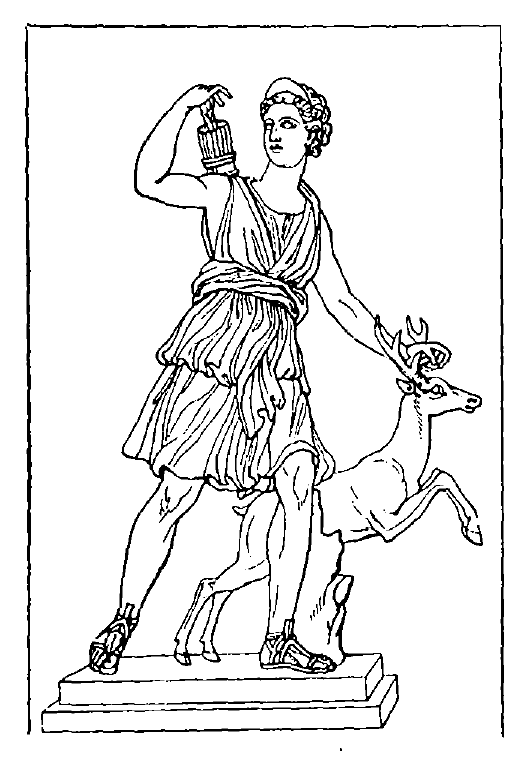

Oeneus, king of Calydon in Ætolia, had incurred the displeasure of Artemis by neglecting to include her in a general sacrifice to the gods which he had offered up, out of gratitude for a bountiful harvest. The goddess, enraged at this neglect, sent a wild boar of extraordinary size and prodigious strength, which destroyed the sprouting grain, laid waste the fields, and threatened the inhabitants with famine and death. At this juncture, Meleager, the brave son of Oeneus, returned from the Argonautic expedition, and finding his country ravaged by this dreadful scourge, entreated the assistance of all the celebrated heroes of the age to join him in hunting the ferocious monster. Among the most famous of those who responded to his call were Jason, Castor and Pollux, Idas and Lynceus, Peleus, Telamon, Admetus, Perithous, and Theseus. The brothers of Althea, wife of Oeneus, joined the hunters, and Meleager also enlisted into his service the fleet-footed huntress Atalanta.

The father of this maiden was Schoeneus, an Arcadian, who, disappointed at the birth of a daughter when he had particularly desired a son, had exposed her on the Parthenian Hill, where he left her to perish. Here she was nursed by a she-bear, and at last found by some hunters, who reared her, and gave her the name of Atalanta. As the maiden grew up, she became an ardent lover of the chase, and was alike distinguished for her beauty and courage. Though often wooed, she led a life of strict celibacy, an oracle having predicted that inevitable misfortune awaited her, should she give herself in marriage to any of her numerous suitors.

Many of the heroes objected to hunt in company with a maiden; but Meleager, who loved Atalanta, overcame their opposition, and the valiant band set out on their expedition. Atalanta was the first to wound the boar with her spear, but not before two of the heroes had met their death from his fierce tusks. After a long and desperate encounter, Meleager succeeded in killing the monster, and presented the head and hide to Atalanta, as trophies of the victory. The uncles of Meleager, however, forcibly took the hide from the maiden, claiming their right to the spoil as next of kin, if Meleager resigned it. Artemis, whose anger was still unappeased, caused a violent quarrel to arise between uncles and nephew, and, in the struggle which ensued, Meleager killed his mother's brothers, and then restored the hide to Atalanta. When Althea beheld the dead bodies of the slain heroes, her grief and anger knew no bounds. She swore to revenge the death of her brothers on her own son, and unfortunately for him, the instrument of vengeance lay ready to her hand.

At the birth of Meleager, the Moirae, or Fates, entered the house of Oeneus, and pointing to a piece of wood then burning on the hearth, declared that as soon as it was consumed the babe would surely die. On hearing this, Althea seized the brand, laid it up carefully in a chest, and henceforth preserved it as her most precious possession. But now, love for her son giving place to the resentment she felt against the murderer of her brothers, she threw the fatal brand into the devouring flames. As it consumed, the vigour of Meleager wasted away, and when it was reduced to ashes, he expired. Repenting too late the terrible effects of her rash deed, Althea, in remorse and despair, took away her own life.

The news of the courage and intrepidity displayed by Atalanta in the famous boar-hunt, being carried to the ears of her father, caused him to acknowledge his long-lost child. Urged by him to choose one of her numerous suitors, she consented to do so, but made it a condition that he alone, who could outstrip her in the race, should become her husband, whilst those she defeated should be put to death by her, with the lance which she bore in her hand. Thus many suitors had perished, for the maiden was unequalled for swiftness of foot, but at last a beautiful youth, named Hippomenes, who had vainly endeavoured to win her love by his assiduous attentions in the chase, ventured to enter the fatal lists. Knowing that only by stratagem could he hope to be successful, he obtained, by the help of Aphrodite, three golden apples from the garden of the Hesperides, which he threw down at intervals during his course. Atalanta, secure of victory, stooped to pick up the tempting fruit, and, in the meantime, Hippomenes arrived at the goal. He became the husband of the lovely Atalanta, but forgot, in his newly found happiness, the gratitude which he owed to Aphrodite, and the goddess withdrew her favour from the pair. Not long after, the prediction which foretold misfortune to Atalanta, in the event of her marriage, was verified, for she and her husband, having strayed unsanctioned into a sacred grove of Zeus, were both transformed into lions.

The trophies of the ever-memorable boar-hunt had been carried by Atalanta into Arcadia, and, for many centuries, the identical hide and enormous tusks of the Calydonian boar hung in the temple of Athene at Tegea. The tusks were afterwards conveyed to Rome, and shown there among other curiosities.

A forcible instance of the manner in which Artemis resented any intrusion on her retirement, is seen in the fate which befell the famous hunter Actaeon, who happening one day to see Artemis and her attendants bathing, imprudently ventured to approach the spot. The goddess, incensed at his audacity, sprinkled him with water, and transformed him into a stag, whereupon he was torn in pieces and devoured by his own dogs.

EPHESIAN ARTEMIS.

The Ephesian Artemis, known to us as "Diana of the Ephesians," was a very ancient Asiatic divinity of Persian origin called Metra,[33] whose worship the Greek colonists found already established, when they first settled in Asia Minor, and whom they identified with their own Greek Artemis, though she really possessed but one single attribute in common with their home deity.

Metra was a twofold divinity, and represented, in one phase of her character, all-pervading love; in the other she was the light of heaven; and as Artemis, in her character as Selene, was the only Greek female divinity who represented celestial light, the Greek settlers, according to their custom of fusing foreign deities into their own, seized at once upon this point of resemblance, and decided that Metra should henceforth be regarded as identical with Artemis.

In her character as the love which pervades all nature, and penetrates everywhere, they believed her also to be present in the mysterious Realm of Shades, where she exercised her benign sway, replacing to a certain extent that ancient divinity Hecate, and partly usurping also the place of Persephone, as mistress of the lower world. Thus they believed that it was she who permitted the spirits of the departed to revisit the earth, in order to communicate with those they loved, and to give them timely warning of coming evil. In fact, this great, mighty, and omnipresent power of love, as embodied in the Ephesian Artemis, was believed by the great thinkers of old, to be the ruling spirit of the universe, and it was to her influence, that all the mysterious and beneficent workings of nature were ascribed.

There was a magnificent temple erected to this divinity at Ephesus (a city of Asia Minor), which was ranked among the seven wonders of the world, and was unequalled in beauty and grandeur. The interior of this edifice was adorned with statues and paintings, and contained one hundred and twenty-seven columns, sixty feet in height, each column having been placed there by a different king. The wealth deposited in this temple was enormous, and the goddess was here worshipped with particular awe and solemnity. In the interior of the edifice stood a statue of her, formed of ebony, with lions on her arms and turrets on her head, whilst a number of breasts indicated the fruitfulness of the earth and of nature. Ctesiphon was the principal architect of this world-renowned structure, which, however, was not entirely completed till two hundred and twenty years after the foundation-stone was laid. But the labour of centuries was destroyed in a single night; for a man called Herostratus, seized with the insane desire of making his name famous to all succeeding generations, set fire to it and completely destroyed it.[34] So great was the indignation and sorrow of the Ephesians at this calamity, that they enacted a law, forbidding the incendiary's name to be mentioned, thereby however, defeating their own object, for thus the name of Herostratus has been handed down to posterity, and will live as long as the memory of the famous temple of Ephesus.

BRAURONIAN ARTEMIS.

In ancient times, the country which we now call the Crimea, was known by the name of the Taurica Chersonnesus. It was colonized by Greek settlers, who, finding that the Scythian inhabitants had a native divinity somewhat resembling their own Artemis, identified her with the huntress-goddess of the mother-country. The worship of this Taurian Artemis was attended with the most barbarous practices, for, in accordance with a law which she had enacted, all strangers, whether male or female, landing, or shipwrecked on her shores, were sacrificed upon her altars. It is supposed that this decree was issued by the Taurian goddess of Chastity, to protect the purity of her followers, by keeping them apart from foreign influences.

The interesting story of Iphigenia, a priestess in the temple of Artemis at Tauris, forms the subject of one of Schiller's most beautiful plays. The circumstances occurred at the commencement of the Trojan war, and are as follows:—The fleet, collected by the Greeks for the siege of Troy, had assembled at Aulis, in Bœotia, and was about to set sail, when Agamemnon, the commander-in-chief, had the misfortune to kill accidentally a stag which was grazing in a grove, sacred to Artemis. The offended goddess sent continuous calms that delayed the departure of the fleet, and Calchas, the soothsayer, who had accompanied the expedition, declared that nothing less than the sacrifice of Agamemnon's favorite daughter, Iphigenia, would appease the wrath of the goddess. At these words, the heroic heart of the brave leader sank within him, and he declared that rather than consent to so fearful an alternative, he would give up his share in the expedition and return to Argos. In this dilemma Odysseus and other great generals called a council to discuss the matter, and, after much deliberation, it was decided that private feeling must yield to the welfare of the state. For a long time the unhappy Agamemnon turned a deaf ear to their arguments, but at last they succeeded in persuading him that it was his duty to make the sacrifice. He, accordingly, despatched a messenger to his wife, Clytemnæstra, begging her to send Iphigenia to him, alleging as a pretext that the great hero Achilles desired to make her his wife. Rejoicing at the brilliant destiny which awaited her beautiful daughter, the fond mother at once obeyed the command, and sent her to Aulis. When the maiden arrived at her destination, and discovered, to her horror, the dreadful fate which awaited her, she threw herself in an agony of grief at her father's feet, and with sobs and tears entreated him to have mercy on her, and to spare her young life. But alas! her doom was sealed, and her now repentant and heart-broken father was powerless to avert it. The unfortunate victim was bound to the altar, and already the fatal knife was raised to deal the death-blow, when suddenly Iphigenia disappeared from view, and in her place on the altar, lay a beautiful deer ready to be sacrificed. It was Artemis herself, who, pitying the youth and beauty of her victim, caused her to be conveyed in a cloud to Taurica, where she became one of her priestesses, and intrusted with the charge of her temple; a dignity, however, which necessitated the offering of those human sacrifices presented to Artemis.

Many years passed away, during which time the long and wearisome siege of Troy had come to an end, and the brave Agamemnon had returned home to meet death at the hands of his wife and Aegisthus. But his daughter, Iphigenia, was still an exile from her native country, and continued to perform the terrible duties which her office involved. She had long given up all hopes of ever being restored to her friends, when one day two Greek strangers landed on Taurica's inhospitable shores. These were Orestes and Pylades, whose romantic attachment to each other has made their names synonymous for devoted self-sacrificing friendship. Orestes was Iphigenia's brother, and Pylades her cousin, and their object in undertaking an expedition fraught with so much peril, was to obtain the statue of the Taurian Artemis. Orestes, having incurred the anger of the Furies for avenging the murder of his father Agamemnon, was pursued by them wherever he went, until at last he was informed by the oracle of Delphi that, in order to pacify them, he must convey the image of the Taurian Artemis from Tauris to Attica. This he at once resolved to do, and accompanied by his faithful friend Pylades, who insisted on sharing the dangers of the undertaking, he set out for Taurica. But the unfortunate youths had hardly stepped on shore before they were seized by the natives, who, as usual, conveyed them for sacrifice to the temple of Artemis. Iphigenia, discovering that they were Greeks, though unaware of their near relationship to herself, thought the opportunity a favourable one for sending tidings of her existence to her native country, and, accordingly, requested one of the strangers to be the bearer of a letter from her to her family. A magnanimous dispute now arose between the friends, and each besought the other to accept the precious privilege of life and freedom. Pylades, at length overcome by the urgent entreaties of Orestes, agreed to be the bearer of the missive, but on looking more closely at the superscription, he observed, to his intense surprise, that it was addressed to Orestes. Hereupon an explanation followed; the brother and sister recognized each other, amid joyful tears and loving embraces, and assisted by her friends and kinsmen, Iphigenia escaped with them from a country where she had spent so many unhappy days, and witnessed so many scenes of horror and anguish.

The fugitives, having contrived to obtain the image of the Taurian Artemis, carried it with them to Brauron in Attica. This divinity was henceforth known as the Brauronian Artemis, and the rites which had rendered her worship so infamous in Taurica were now introduced into Greece, and human victims bled freely under the sacrificial knife, both in Athens and Sparta. The revolting practice of offering human sacrifices to her, was continued until the time of Lycurgus, the great Spartan lawgiver, who put an end to it by substituting in its place one, which was hardly less barbarous, namely, the scourging of youths, who were whipped on the altars of the Brauronian Artemis in the most cruel manner; sometimes indeed they expired under the lash, in which case their mothers, far from lamenting their fate, are said to have rejoiced, considering this an honourable death for their sons.

SELENE-ARTEMIS.

Hitherto we have seen Artemis only in the various phases of her terrestrial character; but just as her brother Apollo drew into himself by degrees the attributes of that more ancient divinity Helios, the sun-god, so, in like manner, she came to be identified in later times with Selene, the moon-goddess, in which character she is always represented as wearing on her forehead a glittering crescent, whilst a flowing veil, bespangled with stars, reaches to her feet, and a long robe completely envelops her.

DIANA.

The Diana of the Romans was identified with the Greek Artemis, with whom she shares that peculiar tripartite character, which so strongly marks the individuality of the Greek goddess. In heaven she was Luna (the moon), on earth Diana (the huntress-goddess), and in the lower world Proserpine; but, unlike the Ephesian Artemis, Diana, in her character as Proserpine, carries with her into the lower world no element of love or sympathy; she is, on the contrary, characterized by practices altogether hostile to man, such as the exercise of witchcraft, evil charms, and other antagonistic influences, and is, in fact, the Greek Hecate, in her later development.

The statues of Diana were generally erected at a point where three roads met, for which reason she is called Trivia (from tri, three, and via, way).

A temple was dedicated to her on the Aventine hill by Servius Tullius, who is said to have first introduced the worship of this divinity into Rome.

The Nemoralia, or Grove Festivals, were celebrated in her honour on the 13th of August, on the Lacus Nemorensis, or forest-buried lake, near Aricia. The priest who officiated in her temple on this spot, was always a fugitive slave, who had gained his office by murdering his predecessor, and hence was constantly armed, in order that he might thus be prepared to encounter a new aspirant.

HEPHÆSTUS (Vulcan).

Hephæstus, the son of Zeus and Hera, was the god of fire in its beneficial aspect, and the presiding deity over all workmanship accomplished by means of this useful element. He was universally honoured, not only as the god of all mechanical arts, but also as a house and hearth divinity, who exercised a beneficial influence on civilized society in general. Unlike the other Greek divinities, he was ugly and deformed, being awkward in his movements, and limping in his gait. This latter defect originated, as we have already seen, in the wrath of his father Zeus, who hurled him down from heaven[35] in consequence of his taking the part of Hera, in one of the domestic disagreements, which so frequently arose between this royal pair. Hephæstus was a whole day falling from Olympus to the earth, where he at length alighted on the island of Lemnos. The inhabitants of the country, seeing him descending through the air, received him in their arms; but in spite of their care, his leg was broken by the fall, and he remained ever afterwards lame in one foot. Grateful for the kindness of the Lemnians, he henceforth took up his abode in their island, and there built for himself a superb palace, and forges for the pursuit of his avocation. He instructed the people how to work in metals, and also taught them other valuable and useful arts.

It is said that the first work of Hephæstus was a most ingenious throne of gold, with secret springs, which he presented to Hera. It was arranged in such a manner that, once seated, she found herself unable to move, and though all the gods endeavoured to extricate her, their efforts were unavailing. Hephæstus thus revenged himself on his mother for the cruelty she had always displayed towards him, on account of his want of comeliness and grace. Dionysus, the wine god, contrived, however, to intoxicate Hephæstus, and then induced him to return to Olympus, where, after having released the queen of heaven from her very undignified position, he became reconciled to his parents.

He now built for himself a glorious palace on Olympus, of shining gold, and made for the other deities those magnificent edifices which they inhabited. He was assisted in his various and exquisitely skilful works of art, by two female statues of pure gold, formed by his own hand, which possessed the power of motion, and always accompanied him wherever he went. With the assistance of the Cyclops, he forged for Zeus his wonderful thunderbolts, thus investing his mighty father with a new power of terrible import. Zeus testified his appreciation of this precious gift, by bestowing upon Hephæstus the beautiful Aphrodite in marriage,[36] but this was a questionable boon; for the lovely Aphrodite, who was the personification of all grace and beauty, felt no affection for her ungainly and unattractive spouse, and amused herself by ridiculing his awkward movements and unsightly person. On one occasion especially, when Hephæstus good-naturedly took upon himself the office of cup-bearer to the gods, his hobbling gait and extreme awkwardness created the greatest mirth amongst the celestials, in which his disloyal partner was the first to join, with unconcealed merriment.

Aphrodite greatly preferred Ares to her husband, and this preference naturally gave rise to much jealousy on the part of Hephæstus, and caused them great unhappiness.

Hephæstus appears to have been an indispensable member of the Olympic Assembly, where he plays the part of smith, armourer, chariot-builder, &c. As already mentioned, he constructed the palaces where the gods resided, fashioned the golden shoes with which they trod the air or water, built for them their wonderful chariots, and shod with brass the horses of celestial breed, which conveyed these glittering equipages over land and sea. He also made the tripods which moved of themselves in and out of the celestial halls, formed for Zeus the far-famed ægis, and erected the magnificent palace of the sun. He also created the brazen-footed bulls of Aetes, which breathed flames from their nostrils, sent forth clouds of smoke, and filled the air with their roaring.

Among his most renowned works of art for the use of mortals were: the armour of Achilles and Æneas, the beautiful necklace of Harmonia, and the crown of Ariadne; but his masterpiece was Pandora, of whom a detailed account has already been given.

There was a temple on Mount Etna erected in his honour, which none but the pure and virtuous were permitted to enter. The entrance to this temple was guarded by dogs, which possessed the extraordinary faculty of being able to discriminate between the righteous and the unrighteous, fawning upon and caressing the good, whilst they rushed upon all evil-doers and drove them away.

Hephæstus is usually represented as a powerful, brawny, and very muscular man of middle height and mature age; his strong uplifted arm is raised in the act of striking the anvil with a hammer, which he holds in one hand, whilst with the other he is turning a thunderbolt, which an eagle beside him is waiting to carry to Zeus. The principal seat of his worship was the island of Lemnos, where he was regarded with peculiar veneration.

VULCAN.

The Roman Vulcan was merely an importation from Greece, which never at any time took firm root in Rome, nor entered largely into the actual life and sympathies of the nation, his worship being unattended by the devotional feeling and enthusiasm which characterized the religious rites of the other deities. He still, however, retained in Rome his Greek attributes as god of fire, and unrivalled master of the art of working in metals, and was ranked among the twelve great gods of Olympus, whose gilded statues were arranged consecutively along the Forum. His Roman name, Vulcan, would seem to indicate a connection with the first great metal-working artificer of Biblical history, Tubal-Cain.

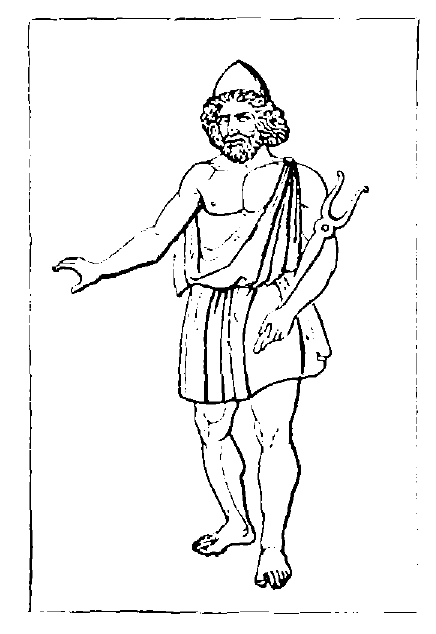

POSEIDON (Neptune).

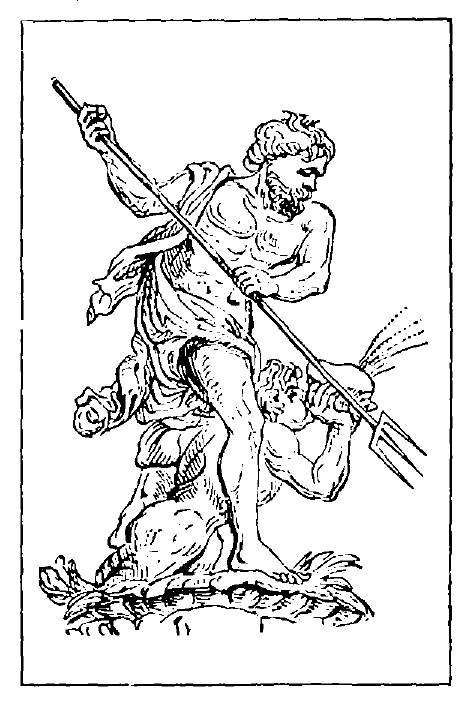

Poseidon was the son of Kronos and Rhea, and the brother of Zeus. He was god of the sea, more particularly of the Mediterranean, and, like the element over which he presided, was of a variable disposition, now violently agitated, and now calm and placid, for which reason he is sometimes represented by the poets as quiet and composed, and at others as disturbed and angry.

In the earliest ages of Greek mythology, he merely symbolized the watery element; but in later times, as navigation and intercourse with other nations engendered greater traffic by sea, Poseidon gained in importance, and came to be regarded as a distinct divinity, holding indisputable dominion over the sea, and over all sea-divinities, who acknowledged him as their sovereign ruler. He possessed the power of causing at will, mighty and destructive tempests, in which the billows rise mountains high, the wind becomes a hurricane, land and sea being enveloped in thick mists, whilst destruction assails the unfortunate mariners exposed to their fury. On the other hand, his alone was the power of stilling the angry waves, of soothing the troubled waters, and granting safe voyages to mariners. For this reason, Poseidon was always invoked and propitiated by a libation before a voyage was undertaken, and sacrifices and thanksgivings were gratefully offered to him after a safe and prosperous journey by sea.

The symbol of his power was the fisherman's fork or trident,[37] by means of which he produced earthquakes, raised up islands from the bottom of the sea, and caused wells to spring forth out of the earth.

Poseidon was essentially the presiding deity over fishermen, and was on that account, more particularly worshipped and revered in countries bordering on the sea-coast, where fish naturally formed a staple commodity of trade. He was supposed to vent his displeasure by sending disastrous inundations, which completely destroyed whole countries, and were usually accompanied by terrible marine monsters, who swallowed up and devoured those whom the floods had spared. It is probable that these sea-monsters are the poetical figures which represent the demons of hunger and famine, necessarily accompanying a general inundation.

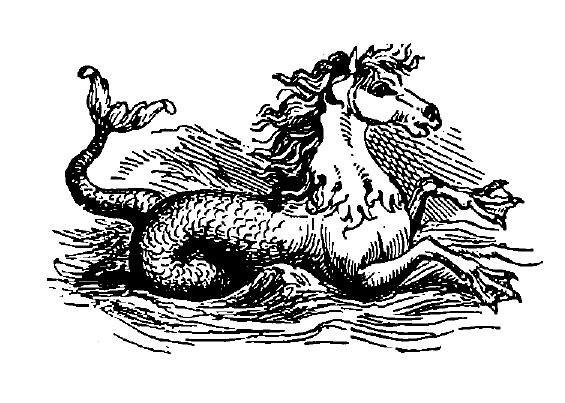

Poseidon is generally represented as resembling his brother Zeus in features, height, and general aspect; but we miss in the countenance of the sea-god the kindness and benignity which so pleasingly distinguish his mighty brother. The eyes are bright and piercing, and the contour of the face somewhat sharper in its outline than that of Zeus, thus corresponding, as it were, with his more angry and violent nature. His hair waves in dark, disorderly masses over his shoulders; his chest is broad, and his frame powerful and stalwart; he wears a short, curling beard, and a band round his head. He usually appears standing erect in a graceful shell-chariot, drawn by hippocamps, or sea-horses, with golden manes and brazen hoofs, who bound over the dancing waves with such wonderful swiftness, that the chariot scarcely touches the water. The monsters of the deep, acknowledging their mighty lord, gambol playfully around him, whilst the sea joyfully smooths a path for the passage of its all-powerful ruler.

He inhabited a beautiful palace at the bottom of the sea at Ægea in Eubœa, and also possessed a royal residence on Mount Olympus, which, however, he only visited when his presence was required at the council of the gods.

His wonderful palace beneath the waters was of vast extent; in its lofty and capacious halls thousands of his followers could assemble. The exterior of the building was of bright gold, which the continual wash of the waters preserved untarnished; in the interior, lofty and graceful columns supported the gleaming dome. Everywhere fountains of glistening, silvery water played; everywhere groves and arbours of feathery-leaved sea-plants appeared, whilst rocks of pure crystal glistened with all the varied colours of the rainbow. Some of the paths were strewn with white sparkling sand, interspersed with jewels, pearls, and amber. This delightful abode was surrounded on all sides by wide fields, where there were whole groves of dark purple coralline, and tufts of beautiful scarlet-leaved plants, and sea-anemones of every tint. Here grew bright, pinky sea-weeds, mosses of all hues and shades, and tall grasses, which, growing upwards, formed emerald caves and grottoes such as the Nereides love, whilst fish of various kinds playfully darted in and out, in the full enjoyment of their native element. Nor was illumination wanting in this fairy-like region, which at night was lit up by the glow-worms of the deep.

But although Poseidon ruled with absolute power over the ocean and its inhabitants, he nevertheless bowed submissively to the will of the great ruler of Olympus, and appeared at all times desirous of conciliating him. We find him coming to his aid when emergency demanded, and frequently rendering him valuable assistance against his opponents. At the time when Zeus was harassed by the attacks of the Giants, he proved himself a most powerful ally, engaging in single combat with a hideous giant named Polybotes, whom he followed over the sea, and at last succeeded in destroying, by hurling upon him the island of Cos.

These amicable relations between the brothers were, however, sometimes interrupted. Thus, for instance, upon one occasion Poseidon joined Hera and Athene in a secret conspiracy to seize upon the ruler of heaven, place him in fetters, and deprive him of the sovereign power. The conspiracy being discovered, Hera, as the chief instigator of this sacrilegious attempt on the divine person of Zeus, was severely chastised, and even beaten, by her enraged spouse, as a punishment for her rebellion and treachery, whilst Poseidon was condemned, for the space of a whole year, to forego his dominion over the sea, and it was at this time that, in conjunction with Apollo, he built for Laomedon the walls of Troy.

Poseidon married a sea-nymph named Amphitrite, whom he wooed under the form of a dolphin. She afterwards became jealous of a beautiful maiden called Scylla, who was beloved by Poseidon, and in order to revenge herself she threw some herbs into a well where Scylla was bathing, which had the effect of metamorphosing her into a monster of terrible aspect, having twelve feet, six heads with six long necks, and a voice which resembled the bark of a dog. This awful monster is said to have inhabited a cave at a very great height in the famous rock which still bears her name,[38] and was supposed to swoop down from her rocky eminence upon every ship that passed, and with each of her six heads to secure a victim.

Amphitrite is often represented assisting Poseidon in attaching the sea-horses to his chariot.

The Cyclops, who have been already alluded to in the history of Cronus, were the sons of Poseidon and Amphitrite. They were a wild race of gigantic growth, similar in their nature to the earth-born Giants, and had only one eye each in the middle of their foreheads. They led a lawless life, possessing neither social manners nor fear of the gods, and were the workmen of Hephæstus, whose workshop was supposed to be in the heart of the volcanic mountain Ætna.

Here we have another striking instance of the manner in which the Greeks personified the powers of nature, which they saw in active operation around them. They beheld with awe, mingled with astonishment, the fire, stones, and ashes which poured forth from the summit of this and other volcanic mountains, and, with their vivacity of imagination, found a solution of the mystery in the supposition, that the god of Fire must be busy at work with his men in the depths of the earth, and that the mighty flames which they beheld, issued in this manner from his subterranean forge.

The chief representative of the Cyclops was the man-eating monster Polyphemus, described by Homer as having been blinded and outwitted at last by Odysseus. This monster fell in love with a beautiful nymph called Galatea; but, as may be supposed, his addresses were not acceptable to the fair maiden, who rejected them in favour of a youth named Acis, upon which Polyphemus, with his usual barbarity, destroyed the life of his rival by throwing upon him a gigantic rock. The blood of the murdered Acis, gushing out of the rock, formed a stream which still bears his name.

Triton, Rhoda,[39] and Benthesicyme were also children of Poseidon and Amphitrite.

The sea-god was the father of two giant sons called Otus and Ephialtes.[40] When only nine years old they were said to be twenty-seven cubits[41] in height and nine in breadth. These youthful giants were as rebellious as they were powerful, even presuming to threaten the gods themselves with hostilities. During the war of the Gigantomachia, they endeavoured to scale heaven by piling mighty mountains one upon another. Already had they succeeded in placing Mount Ossa on Olympus and Pelion on Ossa, when this impious project was frustrated by Apollo, who destroyed them with his arrows. It was supposed that had not their lives been thus cut off before reaching maturity, their sacrilegious designs would have been carried into effect.

Pelias and Neleus were also sons of Poseidon. Their mother Tyro was attached to the river-god Enipeus, whose form Poseidon assumed, and thus won her love. Pelias became afterwards famous in the story of the Argonauts, and Neleus was the father of Nestor, who was distinguished in the Trojan War.

The Greeks believed that it was to Poseidon they were indebted for the existence of the horse, which he is said to have produced in the following manner: Athene and Poseidon both claiming the right to name Cecropia (the ancient name of Athens), a violent dispute arose, which was finally settled by an assembly of the Olympian gods, who decided that whichever of the contending parties presented mankind with the most useful gift, should obtain the privilege of naming the city. Upon this Poseidon struck the ground with his trident, and the horse sprang forth in all his untamed strength and graceful beauty. From the spot which Athene touched with her wand, issued the olive-tree, whereupon the gods unanimously awarded to her the victory, declaring her gift to be the emblem of peace and plenty, whilst that of Poseidon was thought to be the symbol of war and bloodshed. Athene accordingly called the city Athens, after herself, and it has ever since retained this name.

Poseidon tamed the horse for the use of mankind, and was believed to have taught men the art of managing horses by the bridle. The Isthmian games (so named because they were held on the Isthmus of Corinth), in which horse and chariot races were a distinguishing feature, were instituted in honour of Poseidon.

He was more especially worshipped in the Peloponnesus, though universally revered throughout Greece and in the south of Italy. His sacrifices were generally black and white bulls, also wild boars and rams. His usual attributes are the trident, horse, and dolphin.

In some parts of Greece this divinity was identified with the sea-god Nereus, for which reason the Nereides, or daughters of Nereus, are represented as accompanying him.

NEPTUNE.

The Romans worshipped Poseidon under the name of Neptune, and invested him with all the attributes which belong to the Greek divinity.

The Roman commanders never undertook any naval expedition without propitiating Neptune by a sacrifice.

His temple at Rome was in the Campus Martius, and the festivals commemorated in his honour were called Neptunalia.

SEA DIVINITIES.

OCEANUS.

Oceanus was the son of Uranus and Gæa. He was the personification of the ever-flowing stream, which, according to the primitive notions of the early Greeks, encircled the world, and from which sprang all the rivers and streams that watered the earth. He was married to Tethys, one of the Titans, and was the father of a numerous progeny called the Oceanides, who are said to have been three thousand in number. He alone, of all the Titans, refrained from taking part against Zeus in the Titanomachia, and was, on that account, the only one of the primeval divinities permitted to retain his dominion under the new dynasty.

NEREUS.

Nereus appears to have been the personification of the sea in its calm and placid moods, and was, after Poseidon, the most important of the sea-deities. He is represented as a kind and benevolent old man, possessing the gift of prophecy, and presiding more particularly over the Ægean Sea, of which he was considered to be the protecting spirit. There he dwelt with his wife Doris and their fifty blooming daughters, the Nereides, beneath the waves in a beautiful grotto-palace, and was ever ready to assist distressed mariners in the hour of danger.

PROTEUS.

Proteus, more familiarly known as "The Old Man of the Sea," was a son of Poseidon, and gifted with prophetic power. But he had an invincible objection to being consulted in his capacity as seer, and those who wished him to foretell events, watched for the hour of noon, when he was in the habit of coming up to the island of Pharos,[42] with Poseidon's flock of seals, which he tended at the bottom of the sea. Surrounded by these creatures of the deep, he used to slumber beneath the grateful shade of the rocks. This was the favourable moment to seize the prophet, who, in order to avoid importunities, would change himself into an infinite variety of forms. But patience gained the day; for if he were only held long enough, he became wearied at last, and, resuming his true form, gave the information desired, after which he dived down again to the bottom of the sea, accompanied by the animals he tended.

TRITON and the TRITONS.

Triton was the only son of Poseidon and Amphitrite, but he possessed little influence, being altogether a minor divinity. He is usually represented as preceding his father and acting as his trumpeter, using a conch-shell for this purpose. He lived with his parents in their beautiful golden palace beneath the sea at Ægea, and his favourite pastime was to ride over the billows on horses or sea-monsters. Triton is always represented as half man, half fish, the body below the waist terminating in the tail of a dolphin. We frequently find mention of Tritons who are either the offspring or kindred of Triton.

GLAUCUS.

Glaucus is said to have become a sea-divinity in the following manner. While angling one day, he observed that the fish he caught and threw on the bank, at once nibbled at the grass and then leaped back into the water. His curiosity was naturally excited, and he proceeded to gratify it by taking up a few blades and tasting them. No sooner was this done than, obeying an irresistible impulse, he precipitated himself into the deep, and became a sea-god.

Like most sea-divinities he was gifted with prophetic power, and each year visited all the islands and coasts with a train of marine monsters, foretelling all kinds of evil. Hence fishermen dreaded his approach, and endeavoured, by prayer and fasting, to avert the misfortunes which he prophesied. He is often represented floating on the billows, his body covered with mussels, sea-weed, and shells, wearing a full beard and long flowing hair, and bitterly bewailing his immortality.

THETIS.

The silver-footed, fair-haired Thetis, who plays an important part in the mythology of Greece, was the daughter of Nereus, or, as some assert, of Poseidon. Her grace and beauty were so remarkable that Zeus and Poseidon both sought an alliance with her; but, as it had been foretold that a son of hers would gain supremacy over his father, they relinquished their intentions, and she became the wife of Peleus, son of Æacus. Like Proteus, Thetis possessed the power of transforming herself into a variety of different shapes, and when wooed by Peleus she exerted this power in order to elude him. But, knowing that persistence would eventually succeed, he held her fast until she assumed her true form. Their nuptials were celebrated with the utmost pomp and magnificence, and were honoured by the presence of all the gods and goddesses, with the exception of Eris. How the goddess of discord resented her exclusion from the marriage festivities has already been shown.

Thetis ever retained great influence over the mighty lord of heaven, which, as we shall see hereafter, she used in favour of her renowned son, Achilles, in the Trojan War.

When Halcyone plunged into the sea in despair after the shipwreck and death of her husband King Ceyx, Thetis transformed both husband and wife into the birds called kingfishers (halcyones), which, with the tender affection which characterized the unfortunate couple, always fly in pairs. The idea of the ancients was that these birds brought forth their young in nests, which float on the surface of the sea in calm weather, before and after the shortest day, when Thetis was said to keep the waters smooth and tranquil for their especial benefit; hence the term "halcyon-days," which signifies a period of rest and untroubled felicity.

THAUMAS, PHORCYS, and CETO.

The early Greeks, with their extraordinary power of personifying all and every attribute of Nature, gave a distinct personality to those mighty wonders of the deep, which, in all ages, have afforded matter of speculation to educated and uneducated alike. Among these personifications we find Thaumas, Phorcys, and their sister Ceto, who were the offspring of Pontus.

Thaumas (whose name signifies Wonder) typifies that peculiar, translucent condition of the surface of the sea when it reflects, mirror-like, various images, and appears to hold in its transparent embrace the flaming stars and illuminated cities, which are so frequently reflected on its glassy bosom.

Thaumas married the lovely Electra (whose name signifies the sparkling light produced by electricity), daughter of Oceanus. Her amber-coloured hair was of such rare beauty that none of her fair-haired sisters could compare with her, and when she wept, her tears, being too precious to be lost, formed drops of shining amber.

Phorcys and Ceto personified more especially the hidden perils and terrors of the ocean. They were the parents of the Gorgons, the Græa, and the Dragon which guarded the golden apples of the Hesperides.