THE SIEGE OF TROY.

Troy or Ilion was the capital of a kingdom in Asia Minor, situated near the Hellespont, and founded by Ilus, son of Tros. At the time of the famous Trojan war this city was under the government of Priam, a direct descendant of Ilus. Priam was married to Hecuba, daughter of Dymas, king of Thrace; and among the most celebrated of their children were the renowned and valiant Hector, the prophetess Cassandra, and Paris, the cause of the Trojan war.

Before the birth of her second son Paris, Hecuba dreamt that she had given birth to a flaming brand, which was interpreted by Æsacus the seer (a son of Priam by a former marriage) to signify that she would bear a son who would cause the destruction of the city of Troy. Anxious to prevent the fulfilment of the prophecy, Hecuba caused her new-born babe to be exposed on Mount Ida to perish; but being found by some kind-hearted shepherds, the child was reared by them, and grew up unconscious of his noble birth.

As the boy approached manhood he became remarkable, not only for his wonderful beauty of form and feature, but also for his strength and courage, which he exercised in defending the flocks from the attacks of robbers and wild beasts; hence he was called Alexander, or helper of men. It was about this time that he settled the famous dispute concerning the golden apple, thrown by the goddess of Discord into the assembly of the gods. As we have already seen, he gave his decision in favour of Aphrodite; thus creating for himself two implacable enemies, for Hera and Athene never forgave the slight.

Paris became united to a beautiful nymph named Œnone, with whom he lived happily in the seclusion and tranquillity of a pastoral life; but to her deep grief this peaceful existence was not fated to be of long duration.

Hearing that some funereal games were about to be held in Troy in honour of a departed relative of the king, Paris resolved to visit the capital and take part in them himself. There he so greatly distinguished himself in a contest with his unknown brothers, Hector and Deiphobus, that the proud young princes, enraged that an obscure shepherd should snatch from them the prize of victory, were about to create a disturbance, when Cassandra, who had been a spectator of the proceedings, stepped forward, and announced to them that the humble peasant who had so signally defeated them was their own brother Paris. He was then conducted to the presence of his parents, who joyfully acknowledged him as their child; and amidst the festivities and rejoicings in honour of their new-found son the ominous prediction of the past was forgotten.

As a proof of his confidence, the king now intrusted Paris with a somewhat delicate mission. As we have already seen in the Legend of Heracles, that great hero conquered Troy, and after killing king Laomedon, carried away captive his beautiful daughter Hesione, whom he bestowed in marriage on his friend Telamon. But although she became princess of Salamis, and lived happily with her husband, her brother Priam never ceased to regret her loss, and the indignity which had been passed upon his house; and it was now proposed that Paris should be equipped with a numerous fleet, and proceed to Greece in order to demand the restoration of the king's sister.

Before setting out on this expedition, Paris was warned by Cassandra against bringing home a wife from Greece, and she predicted that if he disregarded her injunction he would bring inevitable ruin upon the city of Troy, and destruction to the house of Priam.

Under the command of Paris the fleet set sail, and arrived safely in Greece. Here the young Trojan prince first beheld Helen, the daughter of Zeus and Leda, and sister of the Dioscuri, who was the wife of Menelaus, king of Sparta, and the loveliest woman of her time. The most renowned heroes in Greece had sought the honour of her hand; but her stepfather, Tyndareus, king of Sparta, fearing that if he bestowed her in marriage on one of her numerous lovers he would make enemies of the rest, made it a stipulation that all suitors should solemnly swear to assist and defend the successful candidate, with all the means at their command, in any feud which might hereafter arise in connection with the marriage. He at length conferred the hand of Helen upon Menelaus, a warlike prince, devoted to martial exercises and the pleasures of the chase, to whom he resigned his throne and kingdom.

When Paris arrived at Sparta, and sought hospitality at the royal palace, he was kindly received by king Menelaus. At the banquet given in his honour, he charmed both host and hostess by his graceful manner and varied accomplishments, and specially ingratiated himself with the fair Helen, to whom he presented some rare and chaste trinkets of Asiatic manufacture.

Whilst Paris was still a guest at the court of the king of Sparta, the latter received an invitation from his friend Idomeneus, king of Crete, to join him in a hunting expedition; and Menelaus, being of an unsuspicious and easy temperament, accepted the invitation, leaving to Helen the duty of entertaining the distinguished stranger. Captivated by her surpassing loveliness, the Trojan prince forgot every sense of honour and duty, and resolved to rob his absent host of his beautiful wife. He accordingly collected his followers, and with their assistance stormed the royal castle, possessed himself of the rich treasures which it contained, and succeeded in carrying off its beautiful, and not altogether unwilling mistress.

They at once set sail, but were driven by stress of weather to the island of Crania, where they cast anchor; and it was not until some years had elapsed, during which time home and country were forgotten, that Paris and Helen proceeded to Troy.

Preparations for the War.—When Menelaus heard of the violation of his hearth and home he proceeded to Pylos, accompanied by his brother Agamemnon, in order to consult the wise old king Nestor, who was renowned for his great experience and state-craft. On hearing the facts of the case Nestor expressed it as his opinion that only by means of the combined efforts of all the states of Greece could Menelaus hope to regain Helen in defiance of so powerful a kingdom as that of Troy.

Menelaus and Agamemnon now raised the war-cry, which was unanimously responded to from one end of Greece to the other. Many of those who volunteered their services were former suitors of the fair Helen, and were therefore bound by their oath to support the cause of Menelaus; others joined from pure love of adventure, but one and all were deeply impressed with the disgrace which would attach to their country should such a crime be suffered to go unpunished. Thus a powerful army was collected in which few names of note were missing.

Only in the case of two great heroes, Odysseus (Ulysses) and Achilles, did Menelaus experience any difficulty.

Odysseus, famed for his wisdom and great astuteness, was at this time living happily in Ithaca with his fair young wife Penelope and his little son Telemachus, and was loath to leave his happy home for a perilous foreign expedition of uncertain duration. When therefore his services were solicited he feigned madness; but the shrewd Palamedes, a distinguished hero in the suite of Menelaus, detected and exposed the ruse, and thus Odysseus was forced to join in the war. But he never forgave the interference of Palamedes, and, as we shall see, eventually revenged himself upon him in a most cruel manner.

Achilles was the son of Peleus and the sea-goddess Thetis, who is said to have dipped her son, when a babe, in the river Styx, and thereby rendered him invulnerable, except in the right heel, by which she held him. When the boy was nine years old it was foretold to Thetis that he would either enjoy a long life of inglorious ease and inactivity, or that after a brief career of victory he would die the death of a hero. Naturally desirous of prolonging the life of her son, the fond mother devoutly hoped that the former fate might be allotted to him. With this view she conveyed him to the island of Scyros, in the Ægean Sea, where, disguised as a girl, he was brought up among the daughters of Lycomedes, king of the country.

Now that the presence of Achilles was required, owing to an oracular prediction that Troy could not be taken without him, Menelaus consulted Calchas the soothsayer, who revealed to him the place of his concealment. Odysseus was accordingly despatched to Scyros, where, by means of a clever device, he soon discovered which among the maidens was the object of his search. Disguising himself as a merchant, Odysseus obtained an introduction to the royal palace, where he offered to the king's daughters various trinkets for sale. The girls, with one exception, all examined his wares with unfeigned interest. Observing this circumstance Odysseus shrewdly concluded that the one who held aloof must be none other than the young Achilles himself. But in order further to test the correctness of his deduction, he now exhibited a beautiful set of warlike accoutrements, whilst, at a given signal, stirring strains of martial music were heard outside; whereupon Achilles, fired with warlike ardour, seized the weapons, and thus revealed his identity. He now joined the cause of the Greeks, accompanied at the request of his father by his kinsman Patroclus, and contributed to the expedition a large force of Thessalian troops, or Myrmidons, as they were called, and also fifty ships.

For ten long years Agamemnon and the other chiefs devoted all their energy and means in preparing for the expedition against Troy. But during these warlike preparations an attempt at a peaceful solution of the difficulty was not neglected. An embassy consisting of Menelaus, Odysseus, &c., was despatched to king Priam demanding the surrender of Helen; but though the embassy was received with the utmost pomp and ceremony, the demand was nevertheless rejected; upon which the ambassadors returned to Greece, and the order was given for the fleet to assemble at Aulis, in Bœotia.

Never before in the annals of Greece had so large an army been collected. A hundred thousand warriors were assembled at Aulis, and in its bay floated over a thousand ships, ready to convey them to the Trojan coast. The command of this mighty host was intrusted to Agamemnon, king of Argos, the most powerful of all the Greek princes.

Before the fleet set sail solemn sacrifices were offered to the gods on the sea-shore, when suddenly a serpent was seen to ascend a plane-tree, in which was a sparrow's nest containing nine young ones. The reptile first devoured the young birds and then their mother, after which it was turned by Zeus into stone. Calchas the soothsayer, on being consulted, interpreted the miracle to signify that the war with Troy would last for nine years, and that only in the tenth would the city be taken.

Departure of the Greek Fleet.—The fleet then set sail; but mistaking the Mysian coast for that of Troy, they landed troops and commenced to ravage the country. Telephus, king of the Mysians, who was a son of the great hero Heracles, opposed them with a large army, and succeeded in driving them back to their ships, but was himself wounded in the engagement by the spear of Achilles. Patroclus, who fought valiantly by the side of his kinsman, was also wounded in this battle; but Achilles, who was a pupil of Chiron, carefully bound up the wound, which he succeeded in healing; and from this incident dates the celebrated friendship which ever after existed between the two heroes, who even in death remained united.

The Greeks now returned to Aulis. Meanwhile, the wound of Telephus proving incurable, he consulted an oracle, and the response was, that he alone who had inflicted the wound possessed the power of curing it. Telephus accordingly proceeded to the Greek camp, where he was healed by Achilles, and, at the solicitation of Odysseus, consented to act as guide in the voyage to Troy.

Just as the expedition was about to start for the second time, Agamemnon had the misfortune to kill a hind sacred to Artemis, who, in her anger, sent continuous calms, which prevented the fleet from setting sail. Calchas on being consulted announced that the sacrifice of Iphigenia, the daughter of Agamemnon, would alone appease the incensed goddess. How Agamemnon at length overcame his feelings as a father, and how Iphigenia was saved by Artemis herself, has been already related in a previous chapter.

A fair wind having at length sprung up, the fleet once more set sail. They first stopped at the island of Tenedos, where the famous archer Philoctetes—who possessed the bow and arrows of Heracles, given to him by the dying hero—was bitten in the foot by a venomous snake. So unbearable was the odour emitted by the wound, that, at the suggestion of Odysseus, Philoctetes was conveyed to the island of Lesbos, where, to his great chagrin, he was abandoned to his fate, and the fleet proceeded on their journey to Troy.

Commencement of Hostilities.—Having received early intelligence of the impending invasion of their country, the Trojans sought the assistance of the neighbouring states, who all gallantly responded to their call for help, and thus ample preparations were made to receive the enemy. King Priam being himself too advanced in years for active service, the command of the army devolved upon his eldest son, the brave and valiant Hector.

At the approach of the Greek fleet the Trojans appeared on the coast in order to prevent their landing. But great hesitation prevailed among the troops as to who should be the first to set foot on the enemy's soil, it having been predicted that whoever did so would fall a sacrifice to the Fates. Protesilaus of Phylace, however, nobly disregarding the ominous prediction, leaped on shore, and fell by the hand of Hector.

The Greeks then succeeded in effecting a landing, and in the engagement which ensued the Trojans were signally defeated, and driven to seek safety behind the walls of their city. With Achilles at their head the Greeks now made a desperate attempt to take the city by storm, but were repulsed with terrible losses. After this defeat the invaders, foreseeing a long and wearisome campaign, drew up their ships on land, erected tents, huts, &c., and formed an intrenched camp on the coast.

Between the Greek camp and the city of Troy was a plain watered by the rivers Scamander and Simois, and it was on this plain, afterwards so renowned in history, that the ever memorable battles between the Greeks and Trojans were fought.

The impossibility of taking the city by storm was now recognized by the leaders of the Greek forces. The Trojans, on their side, being less numerous than the enemy, dared not venture on a great battle in the open field; hence the war dragged on for many weary years without any decisive engagement taking place.

It was about this time that Odysseus carried out his long meditated revenge against Palamedes. Palamedes was one of the wisest, most energetic, and most upright of all the Greek heroes, and it was in consequence of his unflagging zeal and wonderful eloquence that most of the chiefs had been induced to join the expedition. But the very qualities which endeared him to the hearts of his countrymen rendered him hateful in the eyes of his implacable enemy, Odysseus, who never forgave his having detected his scheme to avoid joining the army.

In order to effect the ruin of Palamedes, Odysseus concealed in his tent a vast sum of money. He next wrote a letter, purporting to be from king Priam to Palamedes, in which the former thanked the Greek hero effusively for the valuable information received from him, referring at the same time to a large sum of money which he had sent to him as a reward. This letter, which was found upon the person of a Phrygian prisoner, was read aloud in a council of the Greek princes. Palamedes was arraigned before the chiefs of the army and accused of betraying his country to the enemy, whereupon a search was instituted, and a large sum of money being found in his tent, he was pronounced guilty and sentenced to be stoned to death. Though fully aware of the base treachery practised against him, Palamedes offered not a word in self-defence, knowing but too well that, in the face of such damning evidence, the attempt to prove his innocence would be vain.

Defection of Achilles.—During the first year of the campaign the Greeks ravaged the surrounding country, and pillaged the neighbouring villages. Upon one of these foraging expeditions the city of Pedasus was sacked, and Agamemnon, as commander-in-chief, received as his share of the spoil the beautiful Chrysëis, daughter of Chryses, the priest of Apollo; whilst to Achilles was allotted another captive, the fair Brisëis. The following day Chryses, anxious to ransom his daughter, repaired to the Greek camp; but Agamemnon refused to accede to his proposal, and with rude and insulting words drove the old man away. Full of grief at the loss of his child Chryses called upon Apollo for vengeance on her captor. His prayer was heard, and the god sent a dreadful pestilence which raged for ten days in the camp of the Greeks. Achilles at length called together a council, and inquired of Calchas the soothsayer how to arrest this terrible visitation of the gods. The seer replied that Apollo, incensed at the insult offered to his priest, had sent the plague, and that only by the surrender of Chrysëis could his anger be appeased.

On hearing this Agamemnon agreed to resign the maiden; but being already embittered against Calchas for his prediction with regard to his own daughter Iphigenia, he now heaped insults upon the soothsayer and accused him of plotting against his interests. Achilles espoused the cause of Calchas, and a violent dispute arose, in which the son of Thetis would have killed his chief but for the timely interference of Pallas-Athene, who suddenly appeared beside him, unseen by the rest, and recalled him to a sense of the duty he owed to his commander. Agamemnon revenged himself on Achilles by depriving him of his beautiful captive, the fair Brisëis, who had become so attached to her kind and noble captor that she wept bitterly on being removed from his charge. Achilles, now fairly disgusted with the ungenerous conduct of his chief, withdrew himself to his tent, and obstinately declined to take further part in the war.

Heart-sore and dejected he repaired to the sea-shore, and there invoked the presence of his divine mother. In answer to his prayer Thetis emerged from beneath the waves, and comforted her gallant son with the assurance that she would entreat the mighty Zeus to avenge his wrongs by giving victory to the Trojans, so that the Greeks might learn to realize the great loss which they had sustained by his withdrawal from the army. The Trojans being informed by one of their spies of the defection of Achilles, became emboldened by the absence of this brave and intrepid leader, whom they feared above all the other Greek heroes; they accordingly sallied forth, and made a bold and eminently successful attack upon the Greeks, who, although they most bravely and obstinately defended their position, were completely routed, and driven back to their intrenchments, Agamemnon and most of the other Greek leaders being wounded in the engagement.

Encouraged by this marked and signal success the Trojans now commenced to besiege the Greeks in their own camp. At this juncture Agamemnon, seeing the danger which threatened the army, sunk for the moment all personal grievances, and despatched an embassy to Achilles consisting of many noble and distinguished chiefs, urgently entreating him to come to the assistance of his countrymen in this their hour of peril; promising that not only should the fair Brisëis be restored to him, but also that the hand of his own daughter should be bestowed on him in marriage, with seven towns as her dowry. But the obstinate determination of the proud hero was not to be moved; and though he listened courteously to the arguments and representations of the messengers of Agamemnon, his resolution to take no further part in the war remained unshaken.

In one of the engagements which took place soon afterwards, the Trojans, under the command of Hector, penetrated into the heart of the Greek camp, and had already commenced to burn their ships, when Patroclus, seeing the distress of his countrymen, earnestly besought Achilles to send him to the rescue at the head of the Myrmidons. The better nature of the hero prevailed, and he not only intrusted to his friend the command of his brave band of warriors, but lent him also his own suit of armour.

Patroclus having mounted the war-chariot of the hero, Achilles lifted on high a golden goblet and poured out a libation of wine to the gods, accompanied by an earnest petition for victory, and the safe return of his beloved comrade. As a parting injunction he warned Patroclus against advancing too far into the territory of the enemy, and entreated him to be content with rescuing the galleys.

At the head of the Myrmidons Patroclus now made a desperate attack upon the enemy, who, thinking that the invincible Achilles was himself in command of his battalions, became disheartened, and were put to flight. Patroclus followed up his victory and pursued the Trojans as far as the walls of their city, altogether forgetting in the excitement of battle the injunction of his friend Achilles. But his temerity cost the young hero his life, for he now encountered the mighty Hector himself, and fell by his hands. Hector stripped the armour from his dead foe, and would have dragged the body into the city had not Menelaus and Ajax the Greater rushed forward, and after a long and fierce struggle succeeded in rescuing it from desecration.

Death of Hector.—And now came the mournful task of informing Achilles of the fate of his friend. He wept bitterly over the dead body of his comrade, and solemnly vowed that the funereal rites should not be solemnized in his honour until he had slain Hector with his own hands, and captured twelve Trojans to be immolated on his funeral pyre. All other considerations vanished before the burning desire to avenge the death of his friend; and Achilles, now thoroughly aroused from his apathy, became reconciled to Agamemnon, and rejoined the Greek army. At the request of the goddess Thetis, Hephæstus forged for him a new suit of armour, which far surpassed in magnificence that of all the other heroes.

Thus gloriously arrayed he was soon seen striding along, calling the Greeks to arms. He now led the troops against the enemy, who were defeated and put to flight until, near the gates of the city, Achilles and Hector encountered each other. But here, for the first time throughout his whole career, the courage of the Trojan hero deserted him. At the near approach of his redoubtable antagonist he turned and fled for his life. Achilles pursued him; and thrice round the walls of the city was the terrible race run, in sight of the old king and queen, who had mounted the walls to watch the battle. Hector endeavoured, during each course, to reach the city gates, so that his comrades might open them to admit him or cover him with their missiles; but his adversary, seeing his design, forced him into the open plain, at the same time calling to his friends to hurl no spear upon his foe, but to leave to him the vengeance he had so long panted for. At length, wearied with the hot pursuit, Hector made a stand and challenged his foe to single combat. A desperate encounter took place, in which Hector succumbed to his powerful adversary at the Scæan gate; and with his last dying breath the Trojan hero foretold to his conqueror that he himself would soon perish on the same spot.

The infuriated victor bound the lifeless corse of his fallen foe to his chariot, and dragged it three times round the city walls and thence to the Greek camp. Overwhelmed with horror at this terrible scene the aged parents of Hector uttered such heart-rending cries of anguish that they reached the ears of Andromache, his faithful wife, who, rushing to the walls, beheld the dead body of her husband, bound to the conqueror's car.

Achilles now solemnized the funereal rites in honour of his friend Patroclus. The dead body of the hero was borne to the funeral pile by the Myrmidons in full panoply. His dogs and horses were then slain to accompany him, in case he should need them in the realm of shades; after which Achilles, in fulfilment of his savage vow, slaughtered twelve brave Trojan captives, who were laid on the funeral pyre, which was now lighted. When all was consumed the bones of Patroclus were carefully collected and inclosed in a golden urn. Then followed the funereal games, which consisted of chariot-races, fighting with the cestus (a sort of boxing-glove), wrestling matches, foot-races, and single combats with shield and spear, in all of which the most distinguished heroes took part, and contended for the prizes.

Penthesilea.—After the death of Hector, their great hope and bulwark, the Trojans did not venture beyond the walls of their city. But soon their hopes were revived by the appearance of a powerful army of Amazons under the command of their queen Penthesilea, a daughter of Ares, whose great ambition was to measure swords with the renowned Achilles himself, and to avenge the death of the valiant Hector.

Hostilities now recommenced in the open plain. Penthesilea led the Trojan host; the Greeks on their side being under the command of Achilles and Ajax. Whilst the latter succeeded in putting the enemy to flight, Achilles was challenged by Penthesilea to single combat. With heroic courage she went forth to the fight; but even the strongest men failed before the power of the great Achilles, and though a daughter of Ares, Penthesilea was but a woman. With generous chivalry the hero endeavoured to spare the brave and beautiful maiden-warrior, and only when his own life was in imminent danger did he make a serious effort to vanquish his enemy, when Penthesilea shared the fate of all who ventured to oppose the spear of Achilles, and fell by his hand.

Feeling herself fatally wounded, she remembered the desecration of the dead body of Hector, and earnestly entreated the forbearance of the hero. But the petition was hardly necessary, for Achilles, full of compassion for his brave but unfortunate adversary, lifted her gently from the ground, and she expired in his arms.

On beholding the dead body of their leader in the possession of Achilles, the Amazons and Trojans prepared for a fresh attack in order to wrest it from his hands; but observing their purpose, Achilles stepped forward and loudly called upon them to halt. Then in a few well-chosen words he praised the great valour and intrepidity of the fallen queen, and expressed his willingness to resign the body at once.

The chivalrous conduct of Achilles was fully appreciated by both Greeks and Trojans. Thersites alone, a base and cowardly wretch, attributed unworthy motives to the gracious proceedings of the hero; and, not content with these insinuations, he savagely pierced with his lance the dead body of the Amazonian queen; whereupon Achilles, with one blow of his powerful arm, felled him to the ground, and killed him on the spot.

The well-merited death of Thersites excited no commiseration, but his kinsman Diomedes came forward and claimed compensation for the murder of his relative; and as Agamemnon, who, as commander-in-chief, might easily have settled the difficulty, refrained from interfering, the proud nature of Achilles resented the implied condemnation of his conduct, and he once more abandoned the Greek army and took ship for Lesbos. Odysseus, however, followed him to the island, and, with his usual tact, succeeded in inducing the hero to return to the camp.

Death of Achilles.—A new ally of the Trojans now appeared on the field in the person of Memnon, the Æthiopian, a son of Eos and Tithonus, who brought with him a powerful reinforcement of negroes. Memnon was the first opponent who had yet encountered Achilles on an equal footing; for like the great hero himself he was the son of a goddess, and possessed also, like Achilles, a suit of armour made for him by Hephæstus.

Before the heroes encountered each other in single combat, the two goddesses, Thetis and Eos, hastened to Olympus to intercede with its mighty ruler for the life of their sons. Resolved even in this instance not to act in opposition to the Moiræ, Zeus seized the golden scales in which he weighed the lot of mortals, and placed in it the respective fates of the two heroes, whereupon that of Memnon weighed down the balance, thus portending his death.

Eos abandoned Olympus in despair. Arrived on the battlefield she beheld the lifeless body of her son, who, after a long and brave defence, had at length succumbed to the all-conquering arm of Achilles. At her command her children, the Winds, flew down to the plain, and seizing the body of the slain hero conveyed it through the air safe from the desecration of the enemy.

The triumph of Achilles was not of long duration. Intoxicated with success he attempted, at the head of the Greek army, to storm the city of Troy, when Paris, by the aid of Phœbus-Apollo, aimed a well-directed dart at the hero, which pierced his vulnerable heel, and he fell to the ground fatally wounded before the Scæan gate. But though face to face with death, the intrepid hero, raising himself from the ground, still performed prodigies of valour, and not until his tottering limbs refused their office was the enemy aware that the wound was mortal.

By the combined efforts of Ajax and Odysseus the body of Achilles was wrested from the enemy after a long and terrible fight, and conveyed to the Greek camp. Weeping bitterly over the untimely fate of her gallant son, Thetis came to embrace him for the last time, and mingled her regrets and lamentations with those of the whole Greek army. The funeral pyre was then lighted, and the voices of the Muses were heard chanting his funeral dirge. When, according to the custom of the ancients, the body had been burned on the pyre, the bones of the hero were collected, inclosed in a golden urn, and deposited beside the remains of his beloved friend Patroclus.

In the funereal games celebrated in honour of the fallen hero, the property of her son was offered by Thetis as the prize of victory. But it was unanimously agreed that the beautiful suit of armour made by Hephæstus should be awarded to him who had contributed the most to the rescue of the body from the hands of the enemy. Popular opinion unanimously decided in favour of Odysseus, which verdict was confirmed by the Trojan prisoners who were present at the engagement. Unable to endure the slight, the unfortunate Ajax lost his reason, and in this condition put an end to his existence.

Final Measures.—Thus were the Greeks deprived at one and the same time of their bravest and most powerful leader, and of him also who approached the nearest to this distinction. For a time operations were at a standstill, until Odysseus at length, contrived by means of a cleverly-arranged ambush to capture Helenus, the son of Priam. Like his sister Cassandra, Helenus possessed the gift of prophecy, and the unfortunate youth was now coerced by Odysseus into using this gift against the welfare of his native city.

The Greeks learned from the Trojan prince that three conditions were indispensable to the conquest of Troy:—In the first place the son of Achilles must fight in their ranks; secondly, the arrows of Heracles must be used against the enemy; and thirdly, they must obtain possession of the wooden image of Pallas-Athene, the famous Palladium of Troy.

The first condition was easily fulfilled. Ever ready to serve the interests of the community, Odysseus repaired to the island of Scyros, where he found Neoptolemus, the son of Achilles. Having succeeded in arousing the ambition of the fiery youth, he generously resigned to him the magnificent armour of his father, and then conveyed him to the Greek camp, where he immediately distinguished himself in single combat with Eurypylus, the son of Telephus, who had come to the aid of the Trojans.

To procure the poison-dipped arrows of Heracles was a matter of greater difficulty. They were still in the possession of the much-aggrieved Philoctetes, who had remained in the island of Lemnos, his wound still unhealed, suffering the most abject misery. But the judicious zeal of the indefatigable and ever-active Odysseus, who was accompanied in this undertaking by Diomedes, at length gained the day, and he induced Philoctetes to accompany him to the camp, where the skilful leech Machaon, the son of Asclepias, healed him of his wound.

Philoctetes became reconciled to Agamemnon, and in an engagement which took place soon after, he mortally wounded Paris, the son of Priam. But though pierced by the fatal arrow of the demi-god, death did not immediately ensue; and Paris, calling to mind the prediction of an oracle, that his deserted wife Œnone could alone cure him if wounded, caused himself to be transported to her abode on Mount Ida, where he implored her by the memory of their past love to save his life. But mindful only of her wrongs, Œnone crushed out of her heart every womanly feeling of pity and compassion, and sternly bade him depart. Soon, however, all her former affection for her husband awoke within her. With frantic haste she followed him; but on her arrival in the city she found the dead body of Paris already laid on the lighted funeral pile, and, in her remorse and despair, Œnone threw herself on the lifeless form of her husband and perished in the flames.

The Trojans were now shut up within their walls and closely besieged; but the third and most difficult condition being still unfulfilled, all efforts to take the city were unavailing. In this emergency the wise and devoted Odysseus came once more to the aid of his comrades. Having disfigured himself with self-inflicted wounds, he assumed the disguise of a wretched old mendicant, and then crept stealthily into the city in order to discover where the Palladium was preserved. He succeeded in his object, and was recognized by no one save the fair Helen, who after the death of Paris had been given in marriage to his brother Deiphobus. But since death had robbed her of her lover, the heart of the Greek princess had turned yearningly towards her native country and her husband Menelaus, and Odysseus now found in her a most unlooked-for ally. On his return to the camp Odysseus called to his aid the valiant Diomedes, and with his assistance the perilous task of abstracting the Palladium from its sacred precincts was, after some difficulty, effected.

The conditions of conquest being now fulfilled, a council was called to decide on final proceedings. Epeios, a Greek sculptor, who had accompanied the expedition, was desired to construct a colossal wooden horse large enough to contain a number of able and distinguished heroes. On its completion a band of warriors concealed themselves within, whereupon the Greek army broke up their camp, and then set fire to it, as though, wearied of the long and tedious ten years' siege, they had abandoned the enterprise as hopeless.

Accompanied by Agamemnon and the sage Nestor, the fleet set sail for the island of Tenedos, where they cast anchor, anxiously awaiting the torch signal to hasten back to the Trojan coast.

Destruction of Troy.—When the Trojans saw the enemy depart, and the Greek camp in flames, they believed themselves safe at last, and streamed in great numbers out of the town in order to view the site where the Greeks had so long encamped. Here they found the gigantic wooden horse, which they examined with wondering curiosity, various opinions being expressed with regard to its utility. Some supposed it to be an engine of war, and were in favour of destroying it, others regarded it as a sacred idol, and proposed that it should be brought into the city. Two circumstances which now occurred induced the Trojans to incline towards the latter opinion.

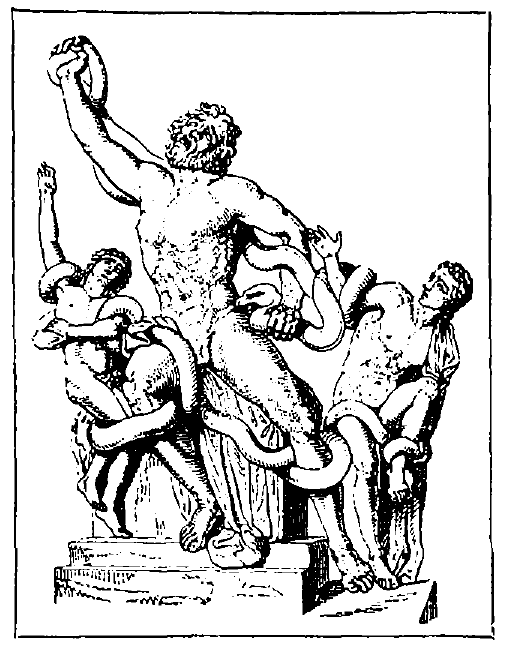

Chief among those who suspected a treacherous design in this huge contrivance was Laocoon, a priest of Apollo, who, in company with his two young sons, had issued from the city with the Trojans in order to offer a sacrifice to the gods. With all the eloquence at his command he urged his countrymen not to place confidence in any gift of the Greeks, and even went so far as to pierce the side of the horse with a spear which he took from a warrior beside him, whereupon the arms of the heroes were heard to rattle. The hearts of the brave men concealed inside the horse quailed within them, and they had already given themselves up for lost, when Pallas-Athene, who ever watched over the cause of the Greeks, now came to their aid, and a miracle occurred in order to blind and deceive the devoted Trojans;—for the fall of Troy was decreed by the gods.

Whilst Laocoon with his two sons stood prepared to perform the sacrifice, two enormous serpents suddenly rose out of the sea, and made direct for the altar. They entwined themselves first round the tender limbs of the helpless youths, and then encircled their father who rushed to their assistance, and thus all three were destroyed in sight of the horrified multitude. The Trojans naturally interpreted the fate of Laocoon and his sons to be a punishment sent by Zeus for his sacrilege against the wooden horse, and were now fully convinced that it must be consecrated to the gods.

The crafty Odysseus had left behind his trusty friend Sinon with full instructions as to his course of action. Assuming the rôle assigned to him, he now approached king Priam with fettered hands and piteous entreaties, alleging that the Greeks, in obedience to the command of an oracle, had attempted to immolate him as a sacrifice; but that he had contrived to escape from their hands, and now sought protection from the king.

The kind-hearted monarch, believing his story, released his bonds, assured him of his favour, and then begged him to explain the true meaning of the wooden horse. Sinon willingly complied. He informed the king that Pallas-Athene, who had hitherto been the hope and stay of the Greeks throughout the war, was so deeply offended at the removal of her sacred image, the Palladium, from her temple in Troy, that she had withdrawn her protection from the Greeks, and refused all further aid till it was restored to its rightful place. Hence the Greeks had returned home in order to seek fresh instructions from an oracle. But before leaving, Calchas the seer had advised their building this gigantic wooden horse as a tribute to the offended goddess, hoping thereby to appease her just anger. He further explained that it had been constructed of such colossal proportions in order to prevent its being brought into the city, so that the favour of Pallas-Athene might not be transferred to the Trojans.

Hardly had the crafty Sinon ceased speaking when the Trojans, with one accord, urged that the wooden horse should be brought into their city without delay. The gates being too low to admit its entrance, a breach was made in the walls, and the horse was conveyed in triumph into the very heart of Troy; whereupon the Trojans, overjoyed at what they deemed the successful issue of the campaign, abandoned themselves to feasting and rioting.

Amidst the universal rejoicing the unhappy Cassandra, foreseeing the result of the admission of the wooden horse into the city, was seen rushing through the streets with wild gestures and dishevelled hair, warning her people against the dangers which awaited them. But her eloquent words fell on deaf ears; for it was ever the fate of the unfortunate prophetess that her predictions should find no credence.

When, after the day's excitement, the Trojans had retired to rest, and all was hushed and silent, Sinon, in the dead of night, released the heroes from their voluntary imprisonment. The signal was then given to the Greek fleet lying off Tenedos, and the whole army in unbroken silence once more landed on the Trojan coast.

To enter the city was now an easy matter, and a fearful slaughter ensued. Aroused from their slumbers, the Trojans, under the command of their bravest leaders, made a gallant defence, but were easily overcome. All their most valiant heroes fell in the fight, and soon the whole city was wrapt in flames.

Priam fell by the hand of Neoptolemus, who killed him as he lay prostrate before the altar of Zeus, praying for divine assistance in this awful hour of peril. The unfortunate Andromache with her young son Astyanax had taken refuge on the summit of a tower, where she was discovered by the victors, who, fearing lest the son of Hector might one day rise against them to avenge the death of his father, tore him from her arms and hurled him over the battlements.

Æneas alone, the son of Aphrodite, the beloved of gods and men, escaped the universal carnage with his son and his old father Anchises, whom he carried on his shoulders out of the city. He first sought refuge on Mount Ida, and afterwards fled to Italy, where he became the ancestral hero of the Roman people.

Menelaus now sought Helen in the royal palace, who, being immortal, still retained all her former beauty and fascination. A reconciliation took place, and she accompanied her husband on his homeward voyage. Andromache, the widow of the brave Hector, was given in marriage to Neoptolemus, Cassandra fell to the share of Agamemnon, and Hecuba, the gray-haired and widowed queen, was made prisoner by Odysseus.

The boundless treasures of the wealthy Trojan king fell into the hands of the Greek heroes, who, after having levelled the city of Troy to the ground, prepared for their homeward voyage.

RETURN OF THE GREEKS FROM TROY.

During the sacking of the city of Troy the Greeks, in the hour of victory, committed many acts of desecration and cruelty, which called down upon them the wrath of the gods, for which reason their homeward voyage was beset with manifold dangers and disasters, and many perished before they reached their native land.

Nestor, Diomedes, Philoctetes, and Neoptolemus were among those who arrived safely in Greece after a prosperous voyage. The vessel which carried Menelaus and Helen was driven by violent tempests to the coast of Egypt, and only after many years of weary wanderings and vicissitudes did they succeed in reaching their home at Sparta.

Ajax the Lesser having offended Pallas-Athene by desecrating her temple on the night of the destruction of Troy, was shipwrecked off Cape Caphareus. He succeeded, however, in clinging to a rock, and his life might have been spared but for his impious boast that he needed not the help of the gods. No sooner had he uttered the sacrilegious words than Poseidon, enraged at his audacity, split with his trident the rock to which the hero was clinging, and the unfortunate Ajax was overwhelmed by the waves.

Fate of Agamemnon.—The homeward voyage of Agamemnon was tolerably uneventful and prosperous; but on his arrival at Mycenæ misfortune and ruin awaited him.

His wife Clytemnestra, in revenge for the sacrifice of her beloved daughter Iphigenia, had formed a secret alliance during his absence with Ægisthus, the son of Thyestes, and on the return of Agamemnon they both conspired to compass his destruction. Clytemnestra feigned the greatest joy on beholding her husband, and in spite of the urgent warnings of Cassandra, who was now a captive in his train, he received her protestations of affection with the most trusting confidence. In her well-assumed anxiety for the comfort of the weary traveller, she prepared a warm bath for his refreshment, and at a given signal from the treacherous queen, Ægisthus, who was concealed in an adjoining chamber, rushed upon the defenceless hero and slew him.

During the massacre of the retainers of Agamemnon which followed, his daughter Electra, with great presence of mind, contrived to save her young brother Orestes. He fled for refuge to his uncle Strophius, king of Phocis, who educated him with his own son Pylades, and an ardent friendship sprung up between the youths, which, from its constancy and disinterestedness, has become proverbial.

As Orestes grew up to manhood, his one great all-absorbing desire was to avenge the death of his father. Accompanied by his faithful friend Pylades, he repaired in disguise to Mycenæ, where Ægisthus and Clytemnestra reigned conjointly over the kingdom of Argos. In order to disarm suspicion he had taken the precaution to despatch a messenger to Clytemnestra, purporting to be sent by king Strophius, to announce to her the untimely death of her son Orestes through an accident during a chariot-race at Delphi.

Arrived at Mycenæ, he found his sister Electra so overwhelmed with grief at the news of her brother's death that to her he revealed his identity. When he heard from her lips how cruelly she had been treated by her mother, and how joyfully the news of his demise had been received, his long pent-up passion completely overpowered him, and rushing into the presence of the king and queen, he first pierced Clytemnestra to the heart, and afterwards her guilty partner.

But the crime of murdering his own mother was not long unavenged by the gods. Hardly was the fatal act committed when the Furies appeared and unceasingly pursued the unfortunate Orestes wherever he went. In this wretched plight he sought refuge in the temple of Delphi, where he earnestly besought Apollo to release him from his cruel tormentors. The god commanded him, in expiation of his crime, to repair to Taurica-Chersonnesus and convey the statue of Artemis from thence to the kingdom of Attica, an expedition fraught with extreme peril. We have already seen in a former chapter how Orestes escaped the fate which befell all strangers who landed on the Taurian coast, and how, with the aid of his sister Iphigenia, the priestess of the temple, he succeeded in conveying the statue of the goddess to his native country.

But the Furies did not so easily relinquish their prey, and only by means of the interposition of the just and powerful goddess Pallas-Athene was Orestes finally liberated from their persecution. His peace of mind being at length restored, Orestes assumed the government of the kingdom of Argos, and became united to the beautiful Hermione, daughter of Helen and Menelaus. On his faithful friend Pylades he bestowed the hand of his beloved sister, the good and faithful Electra.

Homeward Voyage of Odysseus.—With his twelve ships laden with enormous treasures, captured during the sacking of Troy, Odysseus set sail with a light heart for his rocky island home of Ithaca. At length the happy hour had arrived which for ten long years the hero had so anxiously awaited, and he little dreamt that ten more must elapse before he would be permitted by the Fates to clasp to his heart his beloved wife and child.

During his homeward voyage his little fleet was driven by stress of weather to a land whose inhabitants subsisted entirely on a curious plant called the lotus, which was sweet as honey to the taste, but had the effect of causing utter oblivion of home and country, and of creating an irresistible longing to remain for ever in the land of the lotus-eaters. Odysseus and his companions were hospitably received by the inhabitants, who regaled them freely with their peculiar and very delicious food; after partaking of which, however, the comrades of the hero refused to leave the country, and it was only by sheer force that he at length succeeded in bringing them back to their ships.

Polyphemus.—Continuing their journey, they next arrived at the country of the Cyclops, a race of giants remarkable for having only one eye, which was placed in the centre of their foreheads. Here Odysseus, whose love of adventure overcame more prudent considerations, left his fleet safely anchored in the bay of a neighbouring island, and with twelve chosen companions set out to explore the country.

Near the shore they found a vast cave, into which they boldly entered. In the interior they saw to their surprise huge piles of cheese and great pails of milk ranged round the walls. After partaking freely of these provisions his companions endeavoured to persuade Odysseus to return to the ship; but the hero being curious to make the acquaintance of the owner of this extraordinary abode, ordered them to remain and await his pleasure.

Towards evening a fierce giant made his appearance, bearing an enormous load of wood upon his shoulders, and driving before him a large flock of sheep. This was Polyphemus, the son of Poseidon, the owner of the cave. After all his sheep had entered, the giant rolled before the entrance to the cave an enormous rock, which the combined strength of a hundred men would have been powerless to move.

Having kindled a fire of great logs of pine-wood he was about to prepare his supper when the flames revealed to him, in a corner of the cavern, its new occupants, who now came forward and informed him that they were shipwrecked mariners, and claimed his hospitality in the name of Zeus. But the fierce monster railed at the great ruler of Olympus—for the lawless Cyclops knew no fear of the gods—and hardly vouchsafed a reply to the demand of the hero. To the consternation of Odysseus the giant seized two of his companions, and, after dashing them to the ground, consumed their remains, washing down the ghastly meal with huge draughts of milk. He then stretched his gigantic limbs on the ground, and soon fell fast asleep beside the fire.

Thinking the opportunity a favourable one to rid himself and his companions of their terrible enemy, Odysseus drew his sword, and, creeping stealthily forward, was about to slay the giant when he suddenly remembered that the aperture of the cave was effectually closed by the immense rock, which rendered egress impossible. He therefore wisely determined to wait until the following day, and set his wits to work in the meantime to devise a scheme by which he and his companions might make their escape.

When, early next morning, the giant awoke, two more unfortunate companions of the hero were seized by him and devoured; after which Polyphemus leisurely drove out his flock, taking care to secure the entrance of the cave as before.

Next evening the giant devoured two more of his victims, and when he had finished his revolting meal Odysseus stepped forward and presented him with a large measure of wine which he had brought with him from his ship in a goat's skin. Delighted with the delicious beverage the giant inquired the name of the donor. Odysseus replied that his name was Noman, whereupon Polyphemus, graciously announced that he would evince his gratitude by eating him the last.

The monster, thoroughly overcome with the powerful old liquor, soon fell into a heavy sleep, and Odysseus lost no time in putting his plans into execution. He had cut during the day a large piece of the giant's own olive-staff, which he now heated in the fire, and, aided by his companions, thrust it into the eye-ball of Polyphemus, and in this manner effectually blinded him.

The giant made the cave resound with his howls of pain and rage. His cries being heard by his brother Cyclops, who lived in caves not far distant from his own, they soon came trooping over the hills from all sides, and assailed the door of the cave with inquiries concerning the cause of his cries and groans. But as his only reply was, "Noman has injured me," they concluded that he had been playing them a trick, and therefore abandoned him to his fate.

The blinded giant now groped vainly round his cave in hopes of laying hands on some of his tormentors; but wearied at length of these fruitless exertions he rolled away the rock which closed the aperture, thinking that his victims would rush out with the sheep, when it would be an easy matter to capture them. But in the meantime Odysseus had not been idle, and the subtlety of the hero was now brought into play, and proved more than a match for the giant's strength. The sheep were very large, and Odysseus, with bands of willow taken from the bed of Polyphemus, had cleverly linked them together three abreast, and under each centre one had secured one of his comrades. After providing for the safety of his companions, Odysseus himself selected the finest ram of the flock, and, by clinging to the wool of the animal, made his escape. As the sheep passed out of the cave the giant felt carefully among them for his victims, but not finding them on the backs of the animals he let them pass, and thus they all escaped.

They now hastened on board their vessel, and Odysseus, thinking himself at a safe distance, shouted out his real name and mockingly defied the giant; whereupon Polyphemus seized a huge rock, and, following the direction of the voice, hurled it towards the ship, which narrowly escaped destruction. He then called upon his father Poseidon to avenge him, entreating him to curse Odysseus with a long and tedious voyage, to destroy all his ships and all his companions, and to make his return as late, as unhappy, and as desolate as possible.

Further Adventures.—After sailing about over unknown seas for some time the hero and his followers cast anchor at the island of Æolus, king of the Winds, who welcomed them cordially, and sumptuously entertained them for a whole month.

When they took their leave he gave Odysseus the skin of an ox, into which he had placed all the contrary winds in order to insure to them a safe and speedy voyage, and then, having cautioned him on no account to open it, caused the gentle Zephyrus to blow so that he might waft them to the shores of Greece.

On the evening of the tenth day after their departure they arrived in sight of the watch-fires of Ithaca. But here, unfortunately, Odysseus, being completely wearied out, fell asleep, and his comrades, thinking Æolus had given him a treasure in the bag which he so sedulously guarded, seized this opportunity of opening it, whereupon all the adverse winds rushed out, and drove them back to the Æolian island. This time, however, Æolus did not welcome them as before, but dismissed them with bitter reproaches and upbraidings for their disregard of his injunctions.

After a six days' voyage they at length sighted land. Observing what appeared to be the smoke from a large town, Odysseus despatched a herald, accompanied by two of his comrades, in order to procure provisions. When they arrived in the city they discovered to their consternation that they had set foot in the land of the Læstrygones, a race of fierce and gigantic cannibals, governed by their king Antiphates. The unfortunate herald was seized and killed by the king; but his two companions, who took to flight, succeeded in reaching their ship in safety, and urgently entreated their chief to put to sea without delay.

But Antiphates and his fellow-giants pursued the fugitives to the sea-shore, where they now appeared in large numbers. They seized huge rocks, which they hurled upon the fleet, sinking eleven of the ships with all hands, on board; the vessel under the immediate command of Odysseus being the only one which escaped destruction. In this ship, with his few remaining followers, Odysseus now set sail, but was driven by adverse winds to an island called Ææa.

Circe.—The hero and his companions were in sore need of provisions, but, warned by previous disasters, Odysseus resolved that only a certain number of the ship's crew should be despatched to reconnoitre the country; and on lots being drawn by Odysseus and Eurylochus, it fell to the share of the latter to fill the office of conductor to the little band selected for this purpose.

They soon came to a magnificent marble palace, which was situated in a charming and fertile valley. Here dwelt a beautiful enchantress called Circe, daughter of the sun-god and the sea-nymph Perse. The entrance to her abode was guarded by wolves and lions, who, however, to the great surprise of the strangers, were tame and harmless as lambs. These were, in fact, human beings who, by the wicked arts of the sorceress, had been thus transformed. From within they heard the enchanting voice of the goddess, who was singing a sweet melody as she sat at her work, weaving a web such as immortals alone could produce. She graciously invited them to enter, and all save the prudent and cautious Eurylochus accepted the invitation.

As they trod the wide and spacious halls of tesselated marble objects of wealth and beauty met their view on all sides. The soft and luxuriant couches on which she bade them be seated were studded with silver, and the banquet which she provided for their refreshment was served in vessels of pure gold. But while her unsuspecting guests were abandoning themselves to the pleasures of the table the wicked enchantress was secretly working their ruin; for the wine-cup which was presented to them was drugged with a potent draught, after partaking of which the sorceress touched them with her magic wand, and they were immediately transformed into swine, still, however, retaining their human senses.

When Odysseus heard from Eurylochus of the terrible fate which had befallen his companions he set out, regardless of personal danger, resolved to make an effort to rescue them. On his way to the palace of the sorceress he met a fair youth bearing a wand of gold, who revealed himself to him as Hermes, the divine messenger of the gods. He gently reproached the hero for his temerity in venturing to enter the abode of Circe unprovided with an antidote against her spells, and presented him with a peculiar herb called Moly, assuring him that it would inevitably counteract the baneful arts of the fell enchantress. Hermes warned Odysseus that Circe would offer him a draught of drugged wine with the intention of transforming him as she had done his companions. He bade him drink the wine, the effect of which would be completely nullified by the herb which he had given him, and then rush boldly at the sorceress as though he would take her life, whereupon her power over him would cease, she would recognize her master, and grant him whatever he might desire.

Circe received the hero with all the grace and fascination at her command, and presented him with a draught of wine in a golden goblet. This he readily accepted, trusting to the efficacy of the antidote. Then, in obedience to the injunction of Hermes, he drew his sword from its scabbard and rushed upon the sorceress as though he would slay her.

When Circe found that her fell purpose was for the first time frustrated, and that a mortal had dared to attack her, she knew that it must be the great Odysseus who stood before her, whose visit to her abode had been foretold to her by Hermes. At his solicitation she restored to his companions their human form, promising at the same time that henceforth the hero and his comrades should be free from her enchantments.

But all warnings and past experience were forgotten by Odysseus when Circe commenced to exercise upon him her fascinations and blandishments. At her request his companions took up their abode in the island, and he himself became the guest and slave of the enchantress for a whole year; and it was only at the earnest admonition of his friends that he was at length induced to free himself from her toils.

Circe had become so attached to the gallant hero that it cost her a great effort to part with him, but having vowed not to exercise her magic spells against him she was powerless to detain him further. The goddess now warned him that his future would be beset with many dangers, and commanded him to consult the blind old seer Tiresias,[52] in the realm of Hades, concerning his future destiny. She then loaded his ship with provisions for the voyage, and reluctantly bade him farewell.

The Realm of Shades.—Though somewhat appalled at the prospect of seeking the weird and gloomy realms inhabited by the spirits of the dead, Odysseus nevertheless obeyed the command of the goddess, who gave him full directions with regard to his course, and also certain injunctions which it was important that he should carry out with strict attention to detail.

He accordingly set sail with his companions for the dark and gloomy land of the Cimmerians, which lay at the furthermost end of the world, beyond the great stream Oceanus. Favoured by gentle breezes they soon reached their destination in the far west. On arriving at the spot indicated by Circe, where the turbid waters of the rivers Acheron and Cocytus mingled at the entrance to the lower world, Odysseus landed, unattended by his companions.

Having dug a trench to receive the blood of the sacrifices he now offered a black ram and ewe to the powers of darkness, whereupon crowds of shades rose up from the yawning gulf, clustering round him, eager to quaff the blood of the sacrifice, which would restore to them for a time their mental vigour. But mindful of the injunction of Circe, Odysseus brandished his sword, and suffered none to approach until Tiresias had appeared. The great prophet now came slowly forward leaning on his golden staff, and after drinking of the sacrifice proceeded to impart to Odysseus the hidden secrets of his future fate. Tiresias also warned him of the numerous perils which would assail him, not only during his homeward voyage but also on his return to Ithaca, and then instructed him how to avoid them.

Meanwhile numbers of other shades had quaffed the sense-awakening draught of the sacrifice, among whom Odysseus recognized to his dismay his tenderly-loved mother Anticlea. From her he learned that she had died of grief at her son's protracted absence, and that his aged father Laertes was wearing his life away in vain and anxious longings for his return. He also conversed with the ill-fated Agamemnon, Patroclus, and Achilles. The latter bemoaned his shadowy and unreal existence, and plaintively assured his former companion-in-arms that rather would he be the poorest day-labourer on earth than reign supreme as king over the realm of shades. Ajax alone, who still brooded over his wrongs, held aloof, refusing to converse with Odysseus, and sullenly retired when the hero addressed him.

But at last so many shades came swarming round him that the courage of Odysseus failed him, and he fled in terror back to his ship. Having rejoined his companions they once more put to sea, and proceeded on their homeward voyage.

The Sirens.—After some days' sail their course led them past the island of the Sirens.

Now Circe had warned Odysseus on no account to listen to the seductive melodies of these treacherous nymphs; for that all who gave ear to their enticing strains felt an unconquerable desire to leap overboard and join them, when they either perished at their hands, or were engulfed by the waves.

In order that his crew should not hear the song of the Sirens, Odysseus had filled their ears with melted wax; but the hero himself so dearly loved adventure that he could not resist the temptation of braving this new danger. By his own desire, therefore, he was lashed to the mast, and his comrades had strict orders on no account to release him until they were out of sight of the island, no matter how he might implore them to set him free.

As they neared the fatal shore they beheld the Sirens seated side by side on the verdant slopes of their island; and as their sweet and alluring strains fell upon his ear the hero became so powerfully affected by them, that, forgetful of all danger, he entreated his comrades to release him; but the sailors, obedient to their orders, refused to unbind him until the enchanted island had disappeared from view. The danger past, the hero gratefully acknowledged the firmness of his followers, which had been the means of saving his life.

The Island of Helios.—They now approached the terrible dangers of Scylla and Charybdis, between which Circe had desired them to pass. As Odysseus steered the vessel beneath the great rock, Scylla swooped down and seized six of his crew from the deck, and the cries of her wretched victims long rang in his ears. At length they reached the island of Trinacria (Sicily), whereon the sun-god pastured his flocks and herds, and Odysseus, calling to mind the warning of Tiresias to avoid this sacred island, would fain have steered the vessel past and left the country unexplored. But his crew became mutinous, and insisted on landing. Odysseus was therefore obliged to yield, but before allowing them to set foot on shore he made them take an oath not to touch the sacred herds of Helios, and to be ready to sail again on the following morning.

It happened, unfortunately, however, that stress of weather compelled them to remain a whole month at Trinacria, and the store of wine and food given to them by Circe at parting being completely exhausted, they were obliged to subsist on what fish and birds the island afforded. Frequently there was not sufficient to satisfy their hunger, and one evening when Odysseus, worn out with anxiety and fatigue, had fallen asleep, Eurylochus persuaded the hungry men to break their vows and kill some of the sacred oxen.

Dreadful was the anger of Helios, who caused the hides of the slaughtered animals to creep and the joints on the spits to bellow like living cattle, and threatened that unless Zeus punished the impious crew he would withdraw his light from the heavens and shine only in Hades. Anxious to appease the enraged deity Zeus assured him that his cause should be avenged. When, therefore, after feasting for seven days Odysseus and his companions again set sail, the ruler of Olympus caused a terrible storm to overtake them, during which the ship was struck with lightning and went to pieces. All the crew were drowned except Odysseus, who, clinging to a mast, floated about in the open sea for nine days, when, after once more escaping being sucked in by the whirlpool of Charybdis, he was cast ashore on the island of Ogygia.

Calypso.—Ogygia was an island covered with dense forests, where, in the midst of a grove of cypress and poplar, stood the charming grotto-palace of the nymph Calypso, daughter of the Titan Atlas. The entrance to the grotto was entwined with a leafy trellis-work of vine-branches, from which depended clusters of purple and golden grapes; the plashing of fountains gave a delicious sense of coolness to the air, which was filled with the songs of birds, and the ground was carpeted with violets and mosses.

Calypso cordially welcomed the forlorn and shipwrecked hero, and hospitably ministered to his wants. In the course of time she became so greatly attached to him that she offered him immortality and eternal youth if he would consent to remain with her for ever. But the heart of Odysseus turned yearningly towards his beloved wife Penelope and his young son. He therefore refused the boon, and earnestly entreated the gods to permit him to revisit his home. But the curse of Poseidon still followed the unfortunate hero, and for seven long years he was detained on the island by Calypso, sorely against his will.

At length Pallas-Athene interceded with her mighty father on his behalf, and Zeus, yielding to her request, forthwith despatched the fleet-footed Hermes to Calypso, commanding her to permit Odysseus to depart and to provide him with the means of transport.

The goddess, though loath to part with her guest, dared not disobey the commands of the mighty Zeus. She therefore instructed the hero how to construct a raft, for which she herself wove the sails. Odysseus now bade her farewell, and alone and unaided embarked on the frail little craft for his native land.

Nausicaa.—For seventeen days Odysseus contrived to pilot the raft skilfully through all the perils of the deep, directing his course according to the directions of Calypso, and guided by the stars of heaven. On the eighteenth day he joyfully hailed the distant outline of the Phæacian coast, and began to look forward hopefully to temporary rest and shelter. But Poseidon, still enraged with the hero who had blinded and insulted his son, caused an awful tempest to arise, during which the raft was swamped by the waves, and Odysseus only saved himself by clinging for bare life to a portion of the wreck.

For two days and nights he floated about, drifted hither and thither by the angry billows, till at last, after many a narrow escape of his life, the sea-goddess Leucothea came to his aid, and he was cast ashore on the coast of Scheria, the island of the luxurious Phæaces. Worn out with the hardships and dangers he had passed through he crept into a thicket for security, and, lying down on a bed of dried leaves, soon fell fast asleep.