O give you your lowly Preparations again,

The birds stuffed so sweetly that can’t be expected to come at

your call,

Give you these with the peace of mind dearer than all.

Home, Home, Home, sweet Home!”

—Be it ever,’ added Mr Wegg in prose as he glanced about the shop, ‘ever so ghastly, all things considered there’s no place like it.’

‘You said you’d like to ask something; but you haven’t asked it,’ remarked Venus, very unsympathetic in manner.

‘Your peace of mind,’ said Wegg, offering condolence, ‘your peace of mind was in a poor way that night. How’s it going on? is it looking up at all?’

‘She does not wish,’ replied Mr Venus with a comical mixture of indignant obstinacy and tender melancholy, ‘to regard herself, nor yet to be regarded, in that particular light. There’s no more to be said.’

‘Ah, dear me, dear me!’ exclaimed Wegg with a sigh, but eyeing him while pretending to keep him company in eyeing the fire, ‘such is Woman! And I remember you said that night, sitting there as I sat here—said that night when your peace of mind was first laid low, that you had taken an interest in these very affairs. Such is coincidence!’

‘Her father,’ rejoined Venus, and then stopped to swallow more tea, ‘her father was mixed up in them.’

‘You didn’t mention her name, sir, I think?’ observed Wegg, pensively. ‘No, you didn’t mention her name that night.’

‘Pleasant Riderhood.’

‘In—deed!’ cried Wegg. ‘Pleasant Riderhood. There’s something moving in the name. Pleasant. Dear me! Seems to express what she might have been, if she hadn’t made that unpleasant remark—and what she ain’t, in consequence of having made it. Would it at all pour balm into your wounds, Mr Venus, to inquire how you came acquainted with her?’

‘I was down at the water-side,’ said Venus, taking another gulp of tea and mournfully winking at the fire—‘looking for parrots’—taking another gulp and stopping.

Mr Wegg hinted, to jog his attention: ‘You could hardly have been out parrot-shooting, in the British climate, sir?’

‘No, no, no,’ said Venus fretfully. ‘I was down at the water-side, looking for parrots brought home by sailors, to buy for stuffing.’

‘Ay, ay, ay, sir!’

‘—And looking for a nice pair of rattlesnakes, to articulate for a Museum—when I was doomed to fall in with her and deal with her. It was just at the time of that discovery in the river. Her father had seen the discovery being towed in the river. I made the popularity of the subject a reason for going back to improve the acquaintance, and I have never since been the man I was. My very bones is rendered flabby by brooding over it. If they could be brought to me loose, to sort, I should hardly have the face to claim ‘em as mine. To such an extent have I fallen off under it.’

Mr Wegg, less interested than he had been, glanced at one particular shelf in the dark.

‘Why I remember, Mr Venus,’ he said in a tone of friendly commiseration ‘(for I remember every word that falls from you, sir), I remember that you said that night, you had got up there—and then your words was, “Never mind.”’

‘—The parrot that I bought of her,’ said Venus, with a despondent rise and fall of his eyes. ‘Yes; there it lies on its side, dried up; except for its plumage, very like myself. I’ve never had the heart to prepare it, and I never shall have now.’

With a disappointed face, Silas mentally consigned this parrot to regions more than tropical, and, seeming for the time to have lost his power of assuming an interest in the woes of Mr Venus, fell to tightening his wooden leg as a preparation for departure: its gymnastic performances of that evening having severely tried its constitution.

After Silas had left the shop, hat-box in hand, and had left Mr Venus to lower himself to oblivion-point with the requisite weight of tea, it greatly preyed on his ingenuous mind that he had taken this artist into partnership at all. He bitterly felt that he had overreached himself in the beginning, by grasping at Mr Venus’s mere straws of hints, now shown to be worthless for his purpose. Casting about for ways and means of dissolving the connexion without loss of money, reproaching himself for having been betrayed into an avowal of his secret, and complimenting himself beyond measure on his purely accidental good luck, he beguiled the distance between Clerkenwell and the mansion of the Golden Dustman.

For, Silas Wegg felt it to be quite out of the question that he could lay his head upon his pillow in peace, without first hovering over Mr Boffin’s house in the superior character of its Evil Genius. Power (unless it be the power of intellect or virtue) has ever the greatest attraction for the lowest natures; and the mere defiance of the unconscious house-front, with his power to strip the roof off the inhabiting family like the roof of a house of cards, was a treat which had a charm for Silas Wegg.

As he hovered on the opposite side of the street, exulting, the carriage drove up.

Original

‘There’ll shortly be an end of you,’ said Wegg, threatening it with the hat-box. ‘Your varnish is fading.’

Mrs Boffin descended and went in.

‘Look out for a fall, my Lady Dustwoman,’ said Wegg.

Bella lightly descended, and ran in after her.

‘How brisk we are!’ said Wegg. ‘You won’t run so gaily to your old shabby home, my girl. You’ll have to go there, though.’

A little while, and the Secretary came out.

‘I was passed over for you,’ said Wegg. ‘But you had better provide yourself with another situation, young man.’

Mr Boffin’s shadow passed upon the blinds of three large windows as he trotted down the room, and passed again as he went back.

‘Yoop!’ cried Wegg. ‘You’re there, are you? Where’s the bottle? You would give your bottle for my box, Dustman!’

Having now composed his mind for slumber, he turned homeward. Such was the greed of the fellow, that his mind had shot beyond halves, two-thirds, three-fourths, and gone straight to spoliation of the whole. ‘Though that wouldn’t quite do,’ he considered, growing cooler as he got away. ‘That’s what would happen to him if he didn’t buy us up. We should get nothing by that.’

We so judge others by ourselves, that it had never come into his head before, that he might not buy us up, and might prove honest, and prefer to be poor. It caused him a slight tremor as it passed; but a very slight one, for the idle thought was gone directly.

‘He’s grown too fond of money for that,’ said Wegg; ‘he’s grown too fond of money.’ The burden fell into a strain or tune as he stumped along the pavements. All the way home he stumped it out of the rattling streets, piano with his own foot, and forte with his wooden leg, ‘He’s grown too fond of money for that, he’s grown too fond of money.’

Even next day Silas soothed himself with this melodious strain, when he was called out of bed at daybreak, to set open the yard-gate and admit the train of carts and horses that came to carry off the little Mound. And all day long, as he kept unwinking watch on the slow process which promised to protract itself through many days and weeks, whenever (to save himself from being choked with dust) he patrolled a little cinderous beat he established for the purpose, without taking his eyes from the diggers, he still stumped to the tune: He’s grown too fond of money for that, he’s grown too fond of money.’

Chapter 8

THE END OF A LONG JOURNEY

The train of carts and horses came and went all day from dawn to nightfall, making little or no daily impression on the heap of ashes, though, as the days passed on, the heap was seen to be slowly melting. My lords and gentlemen and honourable boards, when you in the course of your dust-shovelling and cinder-raking have piled up a mountain of pretentious failure, you must off with your honourable coats for the removal of it, and fall to the work with the power of all the queen’s horses and all the queen’s men, or it will come rushing down and bury us alive.

Yes, verily, my lords and gentlemen and honourable boards, adapting your Catechism to the occasion, and by God’s help so you must. For when we have got things to the pass that with an enormous treasure at disposal to relieve the poor, the best of the poor detest our mercies, hide their heads from us, and shame us by starving to death in the midst of us, it is a pass impossible of prosperity, impossible of continuance. It may not be so written in the Gospel according to Podsnappery; you may not ‘find these words’ for the text of a sermon, in the Returns of the Board of Trade; but they have been the truth since the foundations of the universe were laid, and they will be the truth until the foundations of the universe are shaken by the Builder. This boastful handiwork of ours, which fails in its terrors for the professional pauper, the sturdy breaker of windows and the rampant tearer of clothes, strikes with a cruel and a wicked stab at the stricken sufferer, and is a horror to the deserving and unfortunate. We must mend it, lords and gentlemen and honourable boards, or in its own evil hour it will mar every one of us.

Old Betty Higden fared upon her pilgrimage as many ruggedly honest creatures, women and men, fare on their toiling way along the roads of life. Patiently to earn a spare bare living, and quietly to die, untouched by workhouse hands—this was her highest sublunary hope.

Nothing had been heard of her at Mr Boffin’s house since she trudged off. The weather had been hard and the roads had been bad, and her spirit was up. A less stanch spirit might have been subdued by such adverse influences; but the loan for her little outfit was in no part repaid, and it had gone worse with her than she had foreseen, and she was put upon proving her case and maintaining her independence.

Faithful soul! When she had spoken to the Secretary of that ‘deadness that steals over me at times’, her fortitude had made too little of it. Oftener and ever oftener, it came stealing over her; darker and ever darker, like the shadow of advancing Death. That the shadow should be deep as it came on, like the shadow of an actual presence, was in accordance with the laws of the physical world, for all the Light that shone on Betty Higden lay beyond Death.

The poor old creature had taken the upward course of the river Thames as her general track; it was the track in which her last home lay, and of which she had last had local love and knowledge. She had hovered for a little while in the near neighbourhood of her abandoned dwelling, and had sold, and knitted and sold, and gone on. In the pleasant towns of Chertsey, Walton, Kingston, and Staines, her figure came to be quite well known for some short weeks, and then again passed on.

She would take her stand in market-places, where there were such things, on market days; at other times, in the busiest (that was seldom very busy) portion of the little quiet High Street; at still other times she would explore the outlying roads for great houses, and would ask leave at the Lodge to pass in with her basket, and would not often get it. But ladies in carriages would frequently make purchases from her trifling stock, and were usually pleased with her bright eyes and her hopeful speech. In these and her clean dress originated a fable that she was well to do in the world: one might say, for her station, rich. As making a comfortable provision for its subject which costs nobody anything, this class of fable has long been popular.

In those pleasant little towns on Thames, you may hear the fall of the water over the weirs, or even, in still weather, the rustle of the rushes; and from the bridge you may see the young river, dimpled like a young child, playfully gliding away among the trees, unpolluted by the defilements that lie in wait for it on its course, and as yet out of hearing of the deep summons of the sea. It were too much to pretend that Betty Higden made out such thoughts; no; but she heard the tender river whispering to many like herself, ‘Come to me, come to me! When the cruel shame and terror you have so long fled from, most beset you, come to me! I am the Relieving Officer appointed by eternal ordinance to do my work; I am not held in estimation according as I shirk it. My breast is softer than the pauper-nurse’s; death in my arms is peacefuller than among the pauper-wards. Come to me!’

There was abundant place for gentler fancies too, in her untutored mind. Those gentlefolks and their children inside those fine houses, could they think, as they looked out at her, what it was to be really hungry, really cold? Did they feel any of the wonder about her, that she felt about them? Bless the dear laughing children! If they could have seen sick Johnny in her arms, would they have cried for pity? If they could have seen dead Johnny on that little bed, would they have understood it? Bless the dear children for his sake, anyhow! So with the humbler houses in the little street, the inner firelight shining on the panes as the outer twilight darkened. When the families gathered in-doors there, for the night, it was only a foolish fancy to feel as if it were a little hard in them to close the shutter and blacken the flame. So with the lighted shops, and speculations whether their masters and mistresses taking tea in a perspective of back-parlour—not so far within but that the flavour of tea and toast came out, mingled with the glow of light, into the street—ate or drank or wore what they sold, with the greater relish because they dealt in it. So with the churchyard on a branch of the solitary way to the night’s sleeping-place. ‘Ah me! The dead and I seem to have it pretty much to ourselves in the dark and in this weather! But so much the better for all who are warmly housed at home.’ The poor soul envied no one in bitterness, and grudged no one anything.

But, the old abhorrence grew stronger on her as she grew weaker, and it found more sustaining food than she did in her wanderings. Now, she would light upon the shameful spectacle of some desolate creature—or some wretched ragged groups of either sex, or of both sexes, with children among them, huddled together like the smaller vermin for a little warmth—lingering and lingering on a doorstep, while the appointed evader of the public trust did his dirty office of trying to weary them out and so get rid of them. Now, she would light upon some poor decent person, like herself, going afoot on a pilgrimage of many weary miles to see some worn-out relative or friend who had been charitably clutched off to a great blank barren Union House, as far from old home as the County Jail (the remoteness of which is always its worst punishment for small rural offenders), and in its dietary, and in its lodging, and in its tending of the sick, a much more penal establishment. Sometimes she would hear a newspaper read out, and would learn how the Registrar General cast up the units that had within the last week died of want and of exposure to the weather: for which that Recording Angel seemed to have a regular fixed place in his sum, as if they were its halfpence. All such things she would hear discussed, as we, my lords and gentlemen and honourable boards, in our unapproachable magnificence never hear them, and from all such things she would fly with the wings of raging Despair.

This is not to be received as a figure of speech. Old Betty Higden however tired, however footsore, would start up and be driven away by her awakened horror of falling into the hands of Charity. It is a remarkable Christian improvement, to have made a pursuing Fury of the Good Samaritan; but it was so in this case, and it is a type of many, many, many.

Two incidents united to intensify the old unreasoning abhorrence—granted in a previous place to be unreasoning, because the people always are unreasoning, and invariably make a point of producing all their smoke without fire.

One day she was sitting in a market-place on a bench outside an inn, with her little wares for sale, when the deadness that she strove against came over her so heavily that the scene departed from before her eyes; when it returned, she found herself on the ground, her head supported by some good-natured market-women, and a little crowd about her.

‘Are you better now, mother?’ asked one of the women. ‘Do you think you can do nicely now?’

‘Have I been ill then?’ asked old Betty.

‘You have had a faint like,’ was the answer, ‘or a fit. It ain’t that you’ve been a-struggling, mother, but you’ve been stiff and numbed.’

‘Ah!’ said Betty, recovering her memory. ‘It’s the numbness. Yes. It comes over me at times.’

Was it gone? the women asked her.

‘It’s gone now,’ said Betty. ‘I shall be stronger than I was afore. Many thanks to ye, my dears, and when you come to be as old as I am, may others do as much for you!’

They assisted her to rise, but she could not stand yet, and they supported her when she sat down again upon the bench.

‘My head’s a bit light, and my feet are a bit heavy,’ said old Betty, leaning her face drowsily on the breast of the woman who had spoken before. ‘They’ll both come nat’ral in a minute. There’s nothing more the matter.’

‘Ask her,’ said some farmers standing by, who had come out from their market-dinner, ‘who belongs to her.’

‘Are there any folks belonging to you, mother?’ said the woman.

‘Yes sure,’ answered Betty. ‘I heerd the gentleman say it, but I couldn’t answer quick enough. There’s plenty belonging to me. Don’t ye fear for me, my dear.’

‘But are any of ‘em near here?’ said the men’s voices; the women’s voices chiming in when it was said, and prolonging the strain.

‘Quite near enough,’ said Betty, rousing herself. ‘Don’t ye be afeard for me, neighbours.’

‘But you are not fit to travel. Where are you going?’ was the next compassionate chorus she heard.

‘I’m a going to London when I’ve sold out all,’ said Betty, rising with difficulty. ‘I’ve right good friends in London. I want for nothing. I shall come to no harm. Thankye. Don’t ye be afeard for me.’

A well-meaning bystander, yellow-legginged and purple-faced, said hoarsely over his red comforter, as she rose to her feet, that she ‘oughtn’t to be let to go’.

‘For the Lord’s love don’t meddle with me!’ cried old Betty, all her fears crowding on her. ‘I am quite well now, and I must go this minute.’

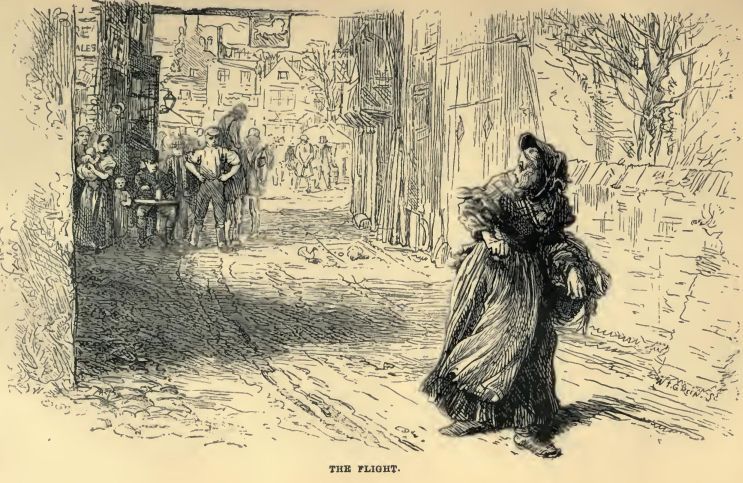

She caught up her basket as she spoke and was making an unsteady rush away from them, when the same bystander checked her with his hand on her sleeve, and urged her to come with him and see the parish-doctor. Strengthening herself by the utmost exercise of her resolution, the poor trembling creature shook him off, almost fiercely, and took to flight. Nor did she feel safe until she had set a mile or two of by-road between herself and the marketplace, and had crept into a copse, like a hunted animal, to hide and recover breath. Not until then for the first time did she venture to recall how she had looked over her shoulder before turning out of the town, and had seen the sign of the White Lion hanging across the road, and the fluttering market booths, and the old grey church, and the little crowd gazing after her but not attempting to follow her.

The second frightening incident was this. She had been again as bad, and had been for some days better, and was travelling along by a part of the road where it touched the river, and in wet seasons was so often overflowed by it that there were tall white posts set up to mark the way. A barge was being towed towards her, and she sat down on the bank to rest and watch it. As the tow-rope was slackened by a turn of the stream and dipped into the water, such a confusion stole into her mind that she thought she saw the forms of her dead children and dead grandchildren peopling the barge, and waving their hands to her in solemn measure; then, as the rope tightened and came up, dropping diamonds, it seemed to vibrate into two parallel ropes and strike her, with a twang, though it was far off. When she looked again, there was no barge, no river, no daylight, and a man whom she had never before seen held a candle close to her face.

‘Now, Missis,’ said he; ‘where did you come from and where are you going to?’

The poor soul confusedly asked the counter-question where she was?

‘I am the Lock,’ said the man.

‘The Lock?’

‘I am the Deputy Lock, on job, and this is the Lock-house. (Lock or Deputy Lock, it’s all one, while the t’other man’s in the hospital.) What’s your Parish?’

‘Parish!’ She was up from the truckle-bed directly, wildly feeling about her for her basket, and gazing at him in affright.

‘You’ll be asked the question down town,’ said the man. ‘They won’t let you be more than a Casual there. They’ll pass you on to your settlement, Missis, with all speed. You’re not in a state to be let come upon strange parishes ‘ceptin as a Casual.’

‘’Twas the deadness again!’ murmured Betty Higden, with her hand to her head.

‘It was the deadness, there’s not a doubt about it,’ returned the man. ‘I should have thought the deadness was a mild word for it, if it had been named to me when we brought you in. Have you got any friends, Missis?’

‘The best of friends, Master.’

‘I should recommend your looking ‘em up if you consider ‘em game to do anything for you,’ said the Deputy Lock. ‘Have you got any money?’

‘Just a morsel of money, sir.’

‘Do you want to keep it?’

‘Sure I do!’

‘Well, you know,’ said the Deputy Lock, shrugging his shoulders with his hands in his pockets, and shaking his head in a sulkily ominous manner, ‘the parish authorities down town will have it out of you, if you go on, you may take your Alfred David.’

‘Then I’ll not go on.’

‘They’ll make you pay, as fur as your money will go,’ pursued the Deputy, ‘for your relief as a Casual and for your being passed to your Parish.’

‘Thank ye kindly, Master, for your warning, thank ye for your shelter, and good night.’

‘Stop a bit,’ said the Deputy, striking in between her and the door. ‘Why are you all of a shake, and what’s your hurry, Missis?’

‘Oh, Master, Master,’ returned Betty Higden, ‘I’ve fought against the Parish and fled from it, all my life, and I want to die free of it!’

‘I don’t know,’ said the Deputy, with deliberation, ‘as I ought to let you go. I’m a honest man as gets my living by the sweat of my brow, and I may fall into trouble by letting you go. I’ve fell into trouble afore now, by George, and I know what it is, and it’s made me careful. You might be took with your deadness again, half a mile off—or half of half a quarter, for the matter of that—and then it would be asked, Why did that there honest Deputy Lock, let her go, instead of putting her safe with the Parish? That’s what a man of his character ought to have done, it would be argueyfied,’ said the Deputy Lock, cunningly harping on the strong string of her terror; ‘he ought to have handed her over safe to the Parish. That was to be expected of a man of his merits.’

As he stood in the doorway, the poor old careworn wayworn woman burst into tears, and clasped her hands, as if in a very agony she prayed to him.

‘As I’ve told you, Master, I’ve the best of friends. This letter will show how true I spoke, and they will be thankful for me.’

The Deputy Lock opened the letter with a grave face, which underwent no change as he eyed its contents. But it might have done, if he could have read them.

‘What amount of small change, Missis,’ he said, with an abstracted air, after a little meditation, ‘might you call a morsel of money?’

Hurriedly emptying her pocket, old Betty laid down on the table, a shilling, and two sixpenny pieces, and a few pence.

‘If I was to let you go instead of handing you over safe to the Parish,’ said the Deputy, counting the money with his eyes, ‘might it be your own free wish to leave that there behind you?’

‘Take it, Master, take it, and welcome and thankful!’

‘I’m a man,’ said the Deputy, giving her back the letter, and pocketing the coins, one by one, ‘as earns his living by the sweat of his brow;’ here he drew his sleeve across his forehead, as if this particular portion of his humble gains were the result of sheer hard labour and virtuous industry; ‘and I won’t stand in your way. Go where you like.’

Original

She was gone out of the Lock-house as soon as he gave her this permission, and her tottering steps were on the road again. But, afraid to go back and afraid to go forward; seeing what she fled from, in the sky-glare of the lights of the little town before her, and leaving a confused horror of it everywhere behind her, as if she had escaped it in every stone of every market-place; she struck off by side ways, among which she got bewildered and lost. That night she took refuge from the Samaritan in his latest accredited form, under a farmer’s rick; and if—worth thinking of, perhaps, my fellow-Christians—the Samaritan had in the lonely night, ‘passed by on the other side’, she would have most devoutly thanked High Heaven for her escape from him.

The morning found her afoot again, but fast declining as to the clearness of her thoughts, though not as to the steadiness of her purpose. Comprehending that her strength was quitting her, and that the struggle of her life was almost ended, she could neither reason out the means of getting back to her protectors, nor even form the idea. The overmastering dread, and the proud stubborn resolution it engendered in her to die undegraded, were the two distinct impressions left in her failing mind. Supported only by a sense that she was bent on conquering in her life-long fight, she went on.

The time was come, now, when the wants of this little life were passing away from her. She could not have swallowed food, though a table had been spread for her in the next field. The day was cold and wet, but she scarcely knew it. She crept on, poor soul, like a criminal afraid of being taken, and felt little beyond the terror of falling down while it was yet daylight, and being found alive. She had no fear that she would live through another night.

Sewn in the breast of her gown, the money to pay for her burial was still intact. If she could wear through the day, and then lie down to die under cover of the darkness, she would die independent. If she were captured previously, the money would be taken from her as a pauper who had no right to it, and she would be carried to the accursed workhouse. Gaining her end, the letter would be found in her breast, along with the money, and the gentlefolks would say when it was given back to them, ‘She prized it, did old Betty Higden; she was true to it; and while she lived, she would never let it be disgraced by falling into the hands of those that she held in horror.’ Most illogical, inconsequential, and light-headed, this; but travellers in the valley of the shadow of death are apt to be light-headed; and worn-out old people of low estate have a trick of reasoning as indifferently as they live, and doubtless would appreciate our Poor Law more philosophically on an income of ten thousand a year.

So, keeping to byways, and shunning human approach, this troublesome old woman hid herself, and fared on all through the dreary day. Yet so unlike was she to vagrant hiders in general, that sometimes, as the day advanced, there was a bright fire in her eyes, and a quicker beating at her feeble heart, as though she said exultingly, ‘The Lord will see me through it!’

By what visionary hands she was led along upon that journey of escape from the Samaritan; by what voices, hushed in the grave, she seemed to be addressed; how she fancied the dead child in her arms again, and times innumerable adjusted her shawl to keep it warm; what infinite variety of forms of tower and roof and steeple the trees took; how many furious horsemen rode at her, crying, ‘There she goes! Stop! Stop, Betty Higden!’ and melted away as they came close; be these things left untold. Faring on and hiding, hiding and faring on, the poor harmless creature, as though she were a Murderess and the whole country were up after her, wore out the day, and gained the night.

‘Water-meadows, or such like,’ she had sometimes murmured, on the day’s pilgrimage, when she had raised her head and taken any note of the real objects about her. There now arose in the darkness, a great building, full of lighted windows. Smoke was issuing from a high chimney in the rear of it, and there was the sound of a water-wheel at the side. Between her and the building, lay a piece of water, in which the lighted windows were reflected, and on its nearest margin was a plantation of trees. ‘I humbly thank the Power and the Glory,’ said Betty Higden, holding up her withered hands, ‘that I have come to my journey’s end!’

She crept among the trees to the trunk of a tree whence she could see, beyond some intervening trees and branches, the lighted windows, both in their reality and their reflection in the water. She placed her orderly little basket at her side, and sank upon the ground, supporting herself against the tree. It brought to her mind the foot of the Cross, and she committed herself to Him who died upon it. Her strength held out to enable her to arrange the letter in her breast, so as that it could be seen that she had a paper there. It had held out for this, and it departed when this was done.

‘I am safe here,’ was her last benumbed thought. ‘When I am found dead at the foot of the Cross, it will be by some of my own sort; some of the working people who work among the lights yonder. I cannot see the lighted windows now, but they are there. I am thankful for all!’

The darkness gone, and a face bending down.

‘It cannot be the boofer lady?’

‘I don’t understand what you say. Let me wet your lips again with this brandy. I have been away to fetch it. Did you think that I was long gone?’

It is as the face of a woman, shaded by a quantity of rich dark hair. It is the earnest face of a woman who is young and handsome. But all is over with me on earth, and this must be an Angel.

‘Have I been long dead?’

‘I don’t understand what you say. Let me wet your lips again. I hurried all I could, and brought no one back with me, lest you should die of the shock of strangers.’

‘Am I not dead?’

‘I cannot understand what you say. Your voice is so low and broken that I cannot hear you. Do you hear me?’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you mean Yes?’

‘Yes.’

‘I was coming from my work just now, along the path outside (I was up with the night-hands last night), and I heard a groan, and found you lying here.’

‘What work, deary?’

‘Did you ask what work? At the paper-mill.’

‘Where is it?’

‘Your face is turned up to the sky, and you can’t see it. It is close by. You can see my face, here, between you and the sky?’

‘Yes.’

‘Dare I lift you?’

‘Not yet.’

‘Not even lift your head to get it on my arm? I will do it by very gentle degrees. You shall hardly feel it.’

‘Not yet. Paper. Letter.’

‘This paper in your breast?’

‘Bless ye!’

‘Let me wet your lips again. Am I to open it? To read it?’

‘Bless ye!’

She reads it with surprise, and looks down with a new expression and an added interest on the motionless face she kneels beside.

‘I know these names. I have heard them often.’

‘Will you send it, my dear?’

‘I cannot understand you. Let me wet your lips again, and your forehead. There. O poor thing, poor thing!’ These words through her fast-dropping tears. ‘What was it that you asked me? Wait till I bring my ear quite close.’

‘Will you send it, my dear?’

‘Will I send it to the writers? Is that your wish? Yes, certainly.’

‘You’ll not give it up to any one but them?’

‘No.’

‘As you must grow old in time, and come to your dying hour, my dear, you’ll not give it up to any one but them?’

‘No. Most solemnly.’

‘Never to the Parish!’ with a convulsed struggle.

‘No. Most solemnly.’

‘Nor let the Parish touch me, not yet so much as look at me!’ with another struggle.

‘No. Faithfully.’

A look of thankfulness and triumph lights the worn old face.

The eyes, which have been darkly fixed upon the sky, turn with meaning in them towards the compassionate face from which the tears are dropping, and a smile is on the aged lips as they ask:

‘What is your name, my dear?’

‘My name is Lizzie Hexam.’

‘I must be sore disfigured. Are you afraid to kiss me?’

The answer is, the ready pressure of her lips upon the cold but smiling mouth.

‘Bless ye! Now lift me, my love.’

Lizzie Hexam very softly raised the weather-stained grey head, and lifted her as high as Heaven.

Chapter 9

SOMEBODY BECOMES THE SUBJECT OF A PREDICTION

‘“We give thee hearty thanks for that it hath pleased thee to deliver this our sister out of the miseries of this sinful world.”’ So read the Reverend Frank Milvey in a not untroubled voice, for his heart misgave him that all was not quite right between us and our sister—or say our sister in Law—Poor Law—and that we sometimes read these words in an awful manner, over our Sister and our Brother too.

And Sloppy—on whom the brave deceased had never turned her back until she ran away from him, knowing that otherwise he would not be separated from her—Sloppy could not in his conscience as yet find the hearty thanks required of it. Selfish in Sloppy, and yet excusable, it may be humbly hoped, because our sister had been more than his mother.

The words were read above the ashes of Betty Higden, in a corner of a churchyard near the river; in a churchyard so obscure that there was nothing in it but grass-mounds, not so much as one single tombstone. It might not be to do an unreasonably great deal for the diggers and hewers, in a registering age, if we ticketed their graves at the common charge; so that a new generation might know which was which: so that the soldier, sailor, emigrant, coming home, should be able to identify the resting-place of father, mother, playmate, or betrothed. For, we turn up our eyes and say that we are all alike in death, and we might turn them down and work the saying out in this world, so far. It would be sentimental, perhaps? But how say ye, my lords and gentleman and honourable boards, shall we not find good standing-room left for a little sentiment, if we look into our crowds?

Near unto the Reverend Frank Milvey as he read, stood his little wife, John Rokesmith the Secretary, and Bella Wilfer. These, over and above Sloppy, were the mourners at the lowly grave. Not a penny had been added to the money sewn in her dress: what her honest spirit had so long projected, was fulfilled.

‘I’ve took it in my head,’ said Sloppy, laying it, inconsolable, against the church door, when all was done: ‘I’ve took it in my wretched head that I might have sometimes turned a little harder for her, and it cuts me deep to think so now.’

The Reverend Frank Milvey, comforting Sloppy, expounded to him how the best of us were more or less remiss in our turnings at our respective Mangles—some of us very much so—and how we were all a halting, failing, feeble, and inconstant crew.

‘She warn’t, sir,’ said Sloppy, taking this ghostly counsel rather ill, in behalf of his late benefactress. ‘Let us speak for ourselves, sir. She went through with whatever duty she had to do. She went through with me, she went through with the Minders, she went through with herself, she went through with everythink. O Mrs Higden, Mrs Higden, you was a woman and a mother and a mangler in a million million!’

With those heartfelt words, Sloppy removed his dejected head from the church door, and took it back to the grave in the corner, and laid it down there, and wept alone. ‘Not a very poor grave,’ said the Reverend Frank Milvey, brushing his hand across his eyes, ‘when it has that homely figure on it. Richer, I think, than it could be made by most of the sculpture in Westminster Abbey!’

They left him undisturbed, and passed out at the wicket-gate. The water-wheel of the paper-mill was audible there, and seemed to have a softening influence on the bright wintry scene. They had arrived but a little while before, and Lizzie Hexam now told them the little she could add to the letter in which she had enclosed Mr Rokesmith’s letter and had asked for their instructions. This was merely how she had heard the groan, and what had afterwards passed, and how she had obtained leave for the remains to be placed in that sweet, fresh, empty store-room of the mill from which they had just accompanied them to the churchyard, and how the last requests had been religiously observed.

‘I could not have done it all, or nearly all, of myself,’ said Lizzie. ‘I should not have wanted the will; but I should not have had the power, without our managing partner.’

‘Surely not the Jew who received us?’ said Mrs Milvey.

(‘My dear,’ observed her husband in parenthesis, ‘why not?’)

‘The gentleman certainly is a Jew,’ said Lizzie, ‘and the lady, his wife, is a Jewess, and I was first brought to their notice by a Jew. But I think there cannot be kinder people in the world.’

‘But suppose they try to convert you!’ suggested Mrs Milvey, bristling in her good little way, as a clergyman’s wife.

‘To do what, ma’am?’ asked Lizzie, with a modest smile.

‘To make you change your religion,’ said Mrs Milvey.

Lizzie shook her head, still smiling. ‘They have never asked me what my religion is. They asked me what my story was, and I told them. They asked me to be industrious and faithful, and I promised to be so. They most willingly and cheerfully do their duty to all of us who are employed here, and we try to do ours to them. Indeed they do much more than their duty to us, for they are wonderfully mindful of us in many ways.’

‘It is easy to see you’re a favourite, my dear,’ said little Mrs Milvey, not quite pleased.

‘It would be very ungrateful in me to say I am not,’ returned Lizzie, ‘for I have been already raised to a place of confidence here. But that makes no difference in their following their own religion and leaving all of us to ours. They never talk of theirs to us, and they never talk of ours to us. If I was the last in the mill, it would be just the same. They never asked me what religion that poor thing had followed.’

‘My dear,’ said Mrs Milvey, aside to the Reverend Frank, ‘I wish you would talk to her.’

‘My dear,’ said the Reverend Frank aside to his good little wife, ‘I think I will leave it to somebody else. The circumstances are hardly favourable. There are plenty of talkers going about, my love, and she will soon find one.’

While this discourse was interchanging, both Bella and the Secretary observed Lizzie Hexam with great attention. Brought face to face for the first time with the daughter of his supposed murderer, it was natural that John Harmon should have his own secret reasons for a careful scrutiny of her countenance and manner. Bella knew that Lizzie’s father had been falsely accused of the crime which had had so great an influence on her own life and fortunes; and her interest, though it had no secret springs, like that of the Secretary, was equally natural. Both had expected to see something very different from the real Lizzie Hexam, and thus it fell out that she became the unconscious means of bringing them together.

For, when they had walked on with her to the little house in the clean village by the paper-mill, where Lizzie had a lodging with an elderly couple employed in the establishment, and when Mrs Milvey and Bella had been up to see her room and had come down, the mill bell rang. This called Lizzie away for the time, and left the Secretary and Bella standing rather awkwardly in the small street; Mrs Milvey being engaged in pursuing the village children, and her investigations whether they were in danger of becoming children of Israel; and the Reverend Frank being engaged—to say the truth—in evading that branch of his spiritual functions, and getting out of sight surreptitiously.

Bella at length said:

‘Hadn’t we better talk about the commission we have undertaken, Mr Rokesmith?’

‘By all means,’ said the Secretary.

‘I suppose,’ faltered Bella, ‘that we are both commissioned, or we shouldn’t both be here?’

‘I suppose so,’ was the Secretary’s answer.

‘When I proposed to come with Mr and Mrs Milvey,’ said Bella, ‘Mrs Boffin urged me to do so, in order that I might give her my small report—it’s not worth anything, Mr Rokesmith, except for it’s being a woman’s—which indeed with you may be a fresh reason for it’s being worth nothing—of Lizzie Hexam.’

‘Mr Boffin,’ said the Secretary, ‘directed me to come for the same purpose.’

As they spoke they were leaving the little street and emerging on the wooded landscape by the river.

‘You think well of her, Mr Rokesmith?’ pursued Bella, conscious of making all the advances.

‘I think highly of her.’

‘I am so glad of that! Something quite refined in her beauty, is there not?’

‘Her appearance is very striking.’

‘There is a shade of sadness upon her that is quite touching. At least I—I am not setting up my own poor opinion, you know, Mr Rokesmith,’ said Bella, excusing and explaining herself in a pretty shy way; ‘I am consulting you.’

‘I noticed that sadness. I hope it may not,’ said the Secretary in a lower voice, ‘be the result of the false accusation which has been retracted.’

When they had passed on a little further without speaking, Bella, after stealing a glance or two at the Secretary, suddenly said:

‘Oh, Mr Rokesmith, don’t be hard with me, don’t be stern with me; be magnanimous! I want to talk with you on equal terms.’

The Secretary as suddenly brightened, and returned: ‘Upon my honour I had no thought but for you. I forced myself to be constrained, lest you might misinterpret my being more natural. There. It’s gone.’

‘Thank you,’ said Bella, holding out her little hand. ‘Forgive me.’

‘No!’ cried the Secretary, eagerly. ‘Forgive me!’ For there were tears in her eyes, and they were prettier in his sight (though they smote him on the heart rather reproachfully too) than any other glitter in the world.

When they had walked a little further:

‘You were going to speak to me,’ said the Secretary, with the shadow so long on him quite thrown off and cast away, ‘about Lizzie Hexam. So was I going to speak to you, if I could have begun.’

‘Now that you can begin, sir,’ returned Bella, with a look as if she italicized the word by putting one of her dimples under it, ‘what were you going to say?’

‘You remember, of course, that in her short letter to Mrs Boffin—short, but containing everything to the purpose—she stipulated that either her name, or else her place of residence, must be kept strictly a secret among us.’

Bella nodded Yes.

‘It is my duty to find out why she made that stipulation. I have it in charge from Mr Boffin to discover, and I am very desirous for myself to discover, whether that retracted accusation still leaves any stain upon her. I mean whether it places her at any disadvantage towards any one, even towards herself.’

‘Yes,’ said Bella, nodding thoughtfully; ‘I understand. That seems wise, and considerate.’

‘You may not have noticed, Miss Wilfer, that she has the same kind of interest in you, that you have in her. Just as you are attracted by her beaut—by her appearance and manner, she is attracted by yours.’

‘I certainly have not noticed it,’ returned Bella, again italicizing with the dimple, ‘and I should have given her credit for—’

The Secretary with a smile held up his hand, so plainly interposing ‘not for better taste’, that Bella’s colour deepened over the little piece of coquetry she was checked in.

‘And so,’ resumed the Secretary, ‘if you would speak with her alone before we go away from here, I feel quite sure that a natural and easy confidence would arise between you. Of course you would not be asked to betray it; and of course you would not, if you were. But if you do not object to put this question to her—to ascertain for us her own feeling in this one matter—you can do so at a far greater advantage than I or any else could. Mr Boffin is anxious on the subject. And I am,’ added the Secretary after a moment, ‘for a special reason, very anxious.’

‘I shall be happy, Mr Rokesmith,’ returned Bella, ‘to be of the least use; for I feel, after the serious scene of to-day, that I am useless enough in this world.’

‘Don’t say that,’ urged the Secretary.

‘Oh, but I mean that,’ said Bella, raising her eyebrows.

‘No one is useless in this world,’ retorted the Secretary, ‘who lightens the burden of it for any one else.’

‘But I assure you I don’t, Mr Rokesmith,’ said Bella, half-crying.

‘Not for your father?’

‘Dear, loving, self-forgetting, easily-satisfied Pa! Oh, yes! He thinks so.’

‘It is enough if he only thinks so,’ said the Secretary. ‘Excuse the interruption: I don’t like to hear you depreciate yourself.’

‘But you once depreciated me, sir,’ thought Bella, pouting, ‘and I hope you may be satisfied with the consequences you brought upon your head!’ However, she said nothing to that purpose; she even said something to a different purpose.

‘Mr Rokesmith, it seems so long since we spoke together naturally, that I am embarrassed in approaching another subject. Mr Boffin. You know I am very grateful to him; don’t you? You know I feel a true respect for him, and am bound to him by the strong ties of his own generosity; now don’t you?’

‘Unquestionably. And also that you are his favourite companion.’

‘That makes it,’ said Bella, ‘so very difficult to speak of him. But—. Does he treat you well?’

‘You see how he treats me,’ the Secretary answered, with a patient and yet proud air.

‘Yes, and I see it with pain,’ said Bella, very energetically.

The Secretary gave her such a radiant look, that if he had thanked her a hundred times, he could not have said as much as the look said.

‘I see it with pain,’ repeated Bella, ‘and it often makes me miserable. Miserable, because I cannot bear to be supposed to approve of it, or have any indirect share in it. Miserable, because I cannot bear to be forced to admit to myself that Fortune is spoiling Mr Boffin.’

‘Miss Wilfer,’ said the Secretary, with a beaming face, ‘if you could know with what delight I make the discovery that Fortune isn’t spoiling you, you would know that it more than compensates me for any slight at any other hands.’

‘Oh, don’t speak of me,’ said Bella, giving herself an impatient little slap with her glove. ‘You don’t know me as well as—’

‘As you know yourself?’ suggested the Secretary, finding that she stopped. ‘Do you know yourself?’

‘I know quite enough of myself,’ said Bella, with a charming air of being inclined to give herself up as a bad job, ‘and I don’t improve upon acquaintance. But Mr Boffin.’

‘That Mr Boffin’s manner to me, or consideration for me, is not what it used to be,’ observed the Secretary, ‘must be admitted. It is too plain to be denied.’

‘Are you disposed to deny it, Mr Rokesmith?’ asked Bella, with a look of wonder.

‘Ought I not to be glad to do so, if I could: though it were only for my own sake?’

‘Truly,’ returned Bella, ‘it must try you very much, and—you must please promise me that you won’t take ill what I am going to add, Mr Rokesmith?’

‘I promise it with all my heart.’

‘—And it must sometimes, I should think,’ said Bella, hesitating, ‘a little lower you in your own estimation?’

Assenting with a movement of his head, though not at all looking as if it did, the Secretary replied:

‘I have very strong reasons, Miss Wilfer, for bearing with the drawbacks of my position in the house we both inhabit. Believe that they are not all mercenary, although I have, through a series of strange fatalities, faded out of my place in life. If what you see with such a gracious and good sympathy is calculated to rouse my pride, there are other considerations (and those you do not see) urging me to quiet endurance. The latter are by far the stronger.’

‘I think I have noticed, Mr Rokesmith,’ said Bella, looking at him with curiosity, as not quite making him out, ‘that you repress yourself, and force yourself, to act a passive part.’

‘You are right. I repress myself and force myself to act a part. It is not in tameness of spirit that I submit. I have a settled purpose.’

‘And a good one, I hope,’ said Bella.

‘And a good one, I hope,’ he answered, looking steadily at her.

‘Sometimes I have fancied, sir,’ said Bella, turning away her eyes, ‘that your great regard for Mrs Boffin is a very powerful motive with you.’

‘You are right again; it is. I would do anything for her, bear anything for her. There are no words to express how I esteem that good, good woman.’

‘As I do too! May I ask you one thing more, Mr Rokesmith?’

‘Anything more.’

‘Of course you see that she really suffers, when Mr Boffin shows how he is changing?’

‘I see it, every day, as you see it, and am grieved to give her pain.’

‘To give her pain?’ said Bella, repeating the phrase quickly, with her eyebrows raised.

‘I am generally the unfortunate cause of it.’

‘Perhaps she says to you, as she often says to me, that he is the best of men, in spite of all.’

‘I often overhear her, in her honest and beautiful devotion to him, saying so to you,’ returned the Secretary, with the same steady look, ‘but I cannot assert that she ever says so to me.’

Bella met the steady look for a moment with a wistful, musing little look of her own, and then, nodding her pretty head several times, like a dimpled philosopher (of the very best school) who was moralizing on Life, heaved a little sigh, and gave up things in general for a bad job, as she had previously been inclined to give up herself.

But, for all that, they had a very pleasant walk. The trees were bare of leaves, and the river was bare of water-lilies; but the sky was not bare of its beautiful blue, and the water reflected it, and a delicious wind ran with the stream, touching the surface crisply. Perhaps the old mirror was never yet made by human hands, which, if all the images it has in its time reflected could pass across its surface again, would fail to reveal some scene of horror or distress. But the great serene mirror of the river seemed as if it might have reproduced all it had ever reflected between those placid banks, and brought nothing to the light save what was peaceful, pastoral, and blooming.

So, they walked, speaking of the newly filled-up grave, and of Johnny, and of many things. So, on their return, they met brisk Mrs Milvey coming to seek them, with the agreeable intelligence that there was no fear for the village children, there being a Christian school in the village, and no worse Judaical interference with it than to plant its garden. So, they got back to the village as Lizzie Hexam was coming from the paper-mill, and Bella detached herself to speak with her in her own home.

‘I am afraid it is a poor room for you,’ said Lizzie, with a smile of welcome, as she offered the post of honour by the fireside.

‘Not so poor as you think, my dear,’ returned Bella, ‘if you knew all.’ Indeed, though attained by some wonderful winding narrow stairs, which seemed to have been erected in a pure white chimney, and though very low in the ceiling, and very rugged in the floor, and rather blinking as to the proportions of its lattice window, it was a pleasanter room than that despised chamber once at home, in which Bella had first bemoaned the miseries of taking lodgers.

The day was closing as the two girls looked at one another by the fireside. The dusky room was lighted by the fire. The grate might have been the old brazier, and the glow might have been the old hollow down by the flare.

‘It’s quite new to me,’ said Lizzie, ‘to be visited by a lady so nearly of my own age, and so pretty, as you. It’s a pleasure to me to look at you.’

‘I have nothing left to begin with,’ returned Bella, blushing, ‘because I was going to say that it was a pleasure to me to look at you, Lizzie. But we can begin without a beginning, can’t we?’

Lizzie took the pretty little hand that was held out in as pretty a little frankness.

‘Now, dear,’ said Bella, drawing her chair a little nearer, and taking Lizzie’s arm as if they were going out for a walk, ‘I am commissioned with something to say, and I dare say I shall say it wrong, but I won’t if I can help it. It is in reference to your letter to Mr and Mrs Boffin, and this is what it is. Let me see. Oh yes! This is what it is.’

With this exordium, Bella set forth that request of Lizzie’s touching secrecy, and delicately spoke of that false accusation and its retraction, and asked might she beg to be informed whether it had any bearing, near or remote, on such request. ‘I feel, my dear,’ said Bella, quite amazing herself by the business-like manner in which she was getting on, ‘that the subject must be a painful one to you, but I am mixed up in it also; for—I don’t know whether you may know it or suspect it—I am the willed-away girl who was to have been married to the unfortunate gentleman, if he had been pleased to approve of me. So I was dragged into the subject without my consent, and you were dragged into it without your consent, and there is very little to choose between us.’

‘I had no doubt,’ said Lizzie, ‘that you were the Miss Wilfer I have often heard named. Can you tell me who my unknown friend is?’

‘Unknown friend, my dear?’ said Bella.

‘Who caused the charge against poor father to be contradicted, and sent me the written paper.’

Bella had never heard of him. Had no notion who he was.

‘I should have been glad to thank him,’ returned Lizzie. ‘He has done a great deal for me. I must hope that he will let me thank him some day. You asked me has it anything to do—’

‘It or the accusation itself,’ Bella put in.

‘Yes. Has either anything to do with my wishing to live quite secret and retired here? No.’

As Lizzie Hexam shook her head in giving this reply and as her glance sought the fire, there was a quiet resolution in her folded hands, not lost on Bella’s bright eyes.

‘Have you lived much alone?’ asked Bella.

‘Yes. It’s nothing new to me. I used to be always alone many hours together, in the day and in the night, when poor father was alive.’

‘You have a brother, I have been told?’

‘I have a brother, but he is not friendly with me. He is a very good boy though, and has raised himself by his industry. I don’t complain of him.’

As she said it, with her eyes upon the fire-glow, there was an instantaneous escape of distress into her face. Bella seized the moment to touch her hand.

‘Lizzie, I wish you would tell me whether you have any friend of your own sex and age.’

‘I have lived that lonely kind of life, that I have never had one,’ was the answer.

‘Nor I neither,’ said Bella. ‘Not that my life has been lonely, for I could have sometimes wished it lonelier, instead of having Ma going on like the Tragic Muse with a face-ache in majestic corners, and Lavvy being spiteful—though of course I am very fond of them both. I wish you could make a friend of me, Lizzie. Do you think you could? I have no more of what they call character, my dear, than a canary-bird, but I know I am trustworthy.’

The wayward, playful, affectionate nature, giddy for want of the weight of some sustaining purpose, and capricious because it was always fluttering among little things, was yet a captivating one. To Lizzie it was so new, so pretty, at once so womanly and so childish, that it won her completely. And when Bella said again, ‘Do you think you could, Lizzie?’ with her eyebrows raised, her head inquiringly on one side, and an odd doubt about it in her own bosom, Lizzie showed beyond all question that she thought she could.

‘Tell me, my dear,’ said Bella, ‘what is the matter, and why you live like this.’

Lizzie presently began, by way of prelude, ‘You must have many lovers—’ when Bella checked her with a little scream of astonishment.

‘My dear, I haven’t one!’

‘Not one?’

‘Well! Perhaps one,’ said Bella. ‘I am sure I don’t know. I had one, but what he may think about it at the present time I can’t say. Perhaps I have half a one (of course I don’t count that Idiot, George Sampson). However, never mind me. I want to hear about you.’

‘There is a certain man,’ said Lizzie, ‘a passionate and angry man, who says he loves me, and who I must believe does love me. He is the friend of my brother. I shrank from him within myself when my brother first brought him to me; but the last time I saw him he terrified me more than I can say.’ There she stopped.

‘Did you come here to escape from him, Lizzie?’

‘I came here immediately after he so alarmed me.’

‘Are you afraid of him here?’

‘I am not timid generally, but I am always afraid of him. I am afraid to see a newspaper, or to hear a word spoken of what is done in London, lest he should have done some violence.’

‘Then you are not afraid of him for yourself, dear?’ said Bella, after pondering on the words.

‘I should be even that, if I met him about here. I look round for him always, as I pass to and fro at night.’

‘Are you afraid of anything he may do to himself in London, my dear?’

‘No. He might be fierce enough even to do some violence to himself, but I don’t think of that.’

‘Then it would almost seem, dear,’ said Bella quaintly, ‘as if there must be somebody else?’

Lizzie put her hands before her face for a moment before replying: ‘The words are always in my ears, and the blow he struck upon a stone wall as he said them is always before my eyes. I have tried hard to think it not worth remembering, but I cannot make so little of it. His hand was trickling down with blood as he said to me, “Then I hope that I may never kill him!’

Rather startled, Bella made and clasped a girdle of her arms round Lizzie’s waist, and then asked quietly, in a soft voice, as they both looked at the fire:

‘Kill him! Is this man so jealous, then?’

‘Of a gentleman,’ said Lizzie. ‘—I hardly know how to tell you—of a gentleman far above me and my way of life, who broke father’s death to me, and has shown an interest in me since.’

‘Does he love you?’

Lizzie shook her head.

‘Does he admire you?’

Lizzie ceased to shake her head, and pressed her hand upon her living girdle.