A CHRONOLOGY OF THE LIFE OF JOSÉ RIZAL

1848, June 28.—Rizal’s parents married in Kalamba, La Laguna: Francisco Rizal-Mercado y Alejandra (born in Biñan, April 18,1818) and Teodora Morales Alonso-Realonda y Quintos (born in Sta. Cruz, Manila, Nov. 14, 1827).

1861, June 19.—Rizal born, their seventh child.

June 22.—Christened as José Protasio Rizal-Mercado y Alonso-Realonda.

1870, Age 9.—In school at Biñan under Master Justiniano Aquin Cruz.

1871, Age 10.—In Kalamba public school under Master Lucas Padua.

1872, June 10. Age 11.—Examined in San Juan de Letran college, Manila, which, during the Spanish time, as part of Sto. Tomás University, controlled entrance to all higher institutions.

June 26.—Entered the Ateneo Municipal de Manila, then a public school, as a day scholar.

1875, June 14. Age 14.—Became a boarder in the Ateneo.

1876, March 23. Age 15.—Received the Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree, with highest honors, from Ateneo de Manila.

June.—Entered Sto. Tomás University in Philosophy course.

1877, June. Age 16.—Matriculated in medical course. Won Liceo Artístico-Literario prize, in poetical competition for “Indians and Mestizos”, with poem “To Philippine Youth.”

Nov. 29.—Awarded diploma of honorable mention and merit by Royal Economic Society of Friends of the Country, Amigos del País, for prize poem.

1880, April 23. Age 19.—Received Liceo Artístico-Literario diploma of honorable mention for allegory “The Council of the Gods,” in competition open to “Spaniards, mestizos and Indians.” Unjustly deprived of first prize.

Dec. 8.—Operetta “On the Banks of the Pasig” produced.

1881. Age 20.—Submitted winning wax model design for commemorative medal for Royal Economic Society of Friends of the Country centennial.

Wounded in the back for not saluting a Guardia Civil lieutenant whom he had not seen. His complaint was ignored by the authorities.

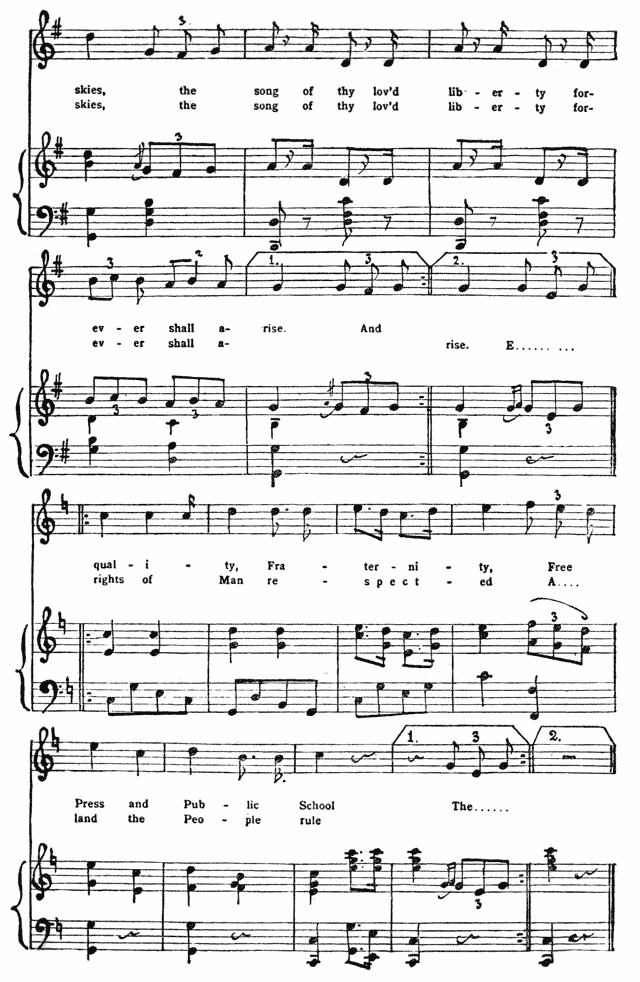

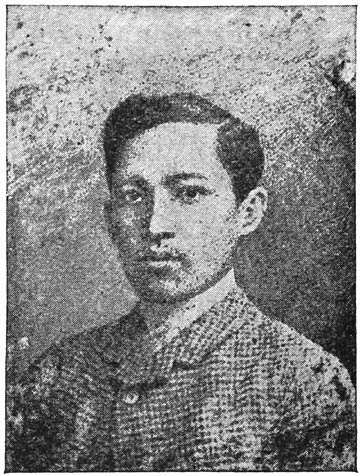

Rizal at 22. From the first photo taken after his arrival in Spain.

1882, May 3. Age 21.—Secretly left Manila, with passport of a cousin, taking at Singapore a French mail steamer for Marseilles and entering Spain at Port Bou by railroad. Money furnished. by his brother, Paciano Mercado.

June.—Absence noted at Sto. Tomás University, which owned Kalamba estate. Rizal’s father was compelled to prove that he had had no knowledge of his son’s plan in order to hold the land on which he was the University’s tenant.

July–Nov.—A student in Barcelona.

Nov. 3.—Began studies in Madrid.

1885, June 19. Age 24—Received degree of Licentiate in Medicine with honors from Central University of Madrid.

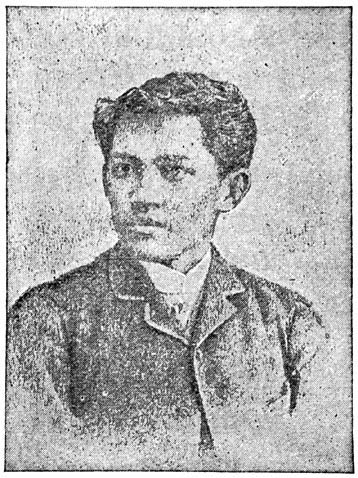

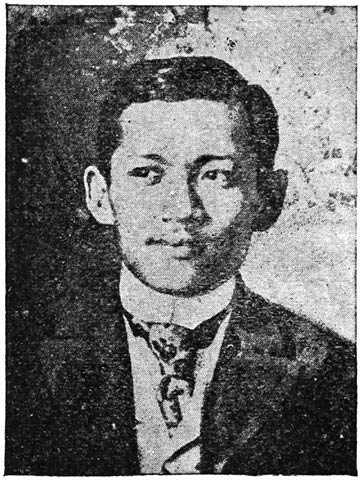

Rizal at 24. The original photograph was taken in Madrid.

1886, June. Age 25—Received degree of Licentiate in Philosophy, with honors and special mention in Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, from Central University of Madrid.

Clinical assistant to Dr. L. de Weckert, a Paris oculist.

Visited Universities of Heidelberg, Leipzig, and Berlin.

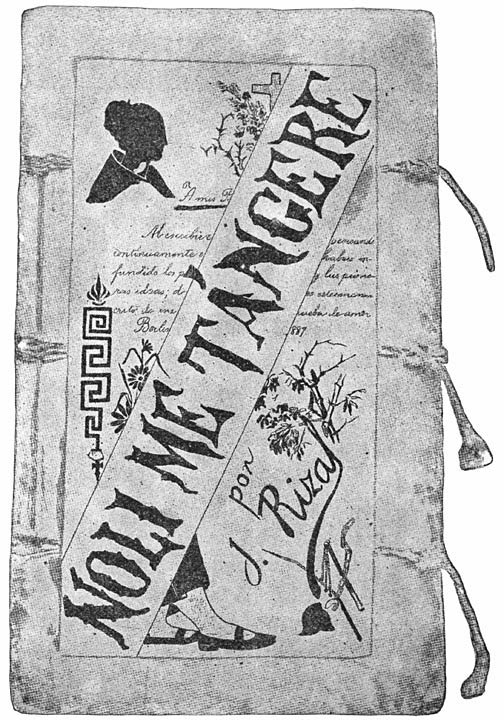

1887, Feb. 21. Age 26—Finished novel Noli Me Tangere in Berlin.

Travelled in Austria, Switzerland and Italy.

July 3.—Sailed from Marseilles.

Aug. 5.—Arrived in Manila. Travelled in nearby provinces with a Spanish lieutenant, detailed by the Governor-General, as escort.

1888, Feb.—Sailed for Japan via Hongkong.

Feb. 28.–Apr. 13. Age 27—A guest at Spanish Legation, Tokyo, and travelling in Japan.

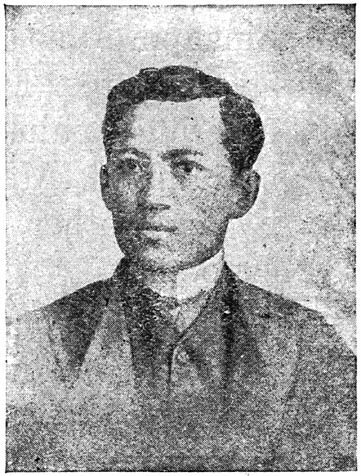

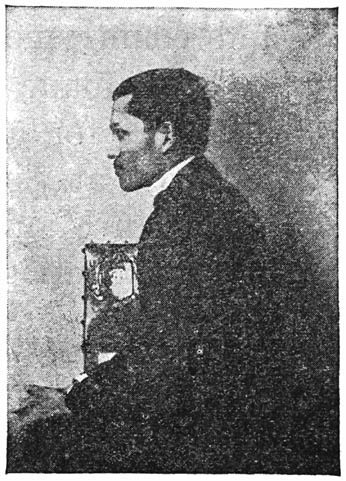

Rizal at 26. From a photo taken in Switzerland.

April–May.—Travelling in the United States.

May 24.—In London, studying in the British Museum to edit Morga’s 1609 Philippine History.

1889, March. Age 28.—In Paris, publishing Morga’s History. Published “The Philippines A Century Hence” in La Solidaridad, a Filipino fortnightly review, first of Barcelona and later of Madrid.

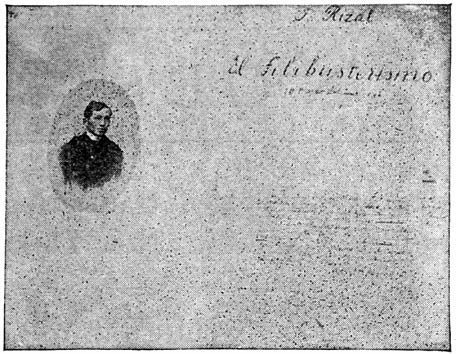

1890, Feb.–July. Age 29.—In Belgium and Holland, finishing El Filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed), which is the sequel to Noli Me Tangere.

Published “The Indolence of the Filipino” in La Solidaridad.

Aug. 4.—Returned to Madrid to confer with countrymen on the Philippine situation, then constantly growing worse.

Rizal at 28. From a group picture, taken in Paris, with the Artist Luna’s family.

1891, Jan. 27.—Left Madrid for France.

Nov. Age 30.—Arranging for a Filipino agricultural colony in British North Borneo.

Practiced medicine in Hongkong.

1892, June 26. Age 31—Returned to Manila under Governor-General Despujol’s safe conduct.

Organized mutual aid economic society Liga Filipina.

July 6.—Ordered deported to Dapitan, but the decree and charges were kept secret from him.

Taught school and conducted a hospital during exile, patients coming from China coast ports for treatment. Fees thus earned were used to beautify the town. Arranged a water system and had the plaza lighted.

1896, Aug. 1. Age 35—Left Dapitan en route to Spain as a volunteer surgeon for the Cuban yellow fever hospitals. Carried letters of recommendation from Governor-General Blanco.

Aug. 7.–Sept. 3.—On Spanish cruiser Castilla in Manila Bay.

Sailed for Spain on Spanish mail steamer and just after leaving Port Said was confined to cabin as a prisoner on cabled order from Manila. (Governor-General Blanco’s promotion had been purchased by Rizal’s enemies to secure appointment of a governor-general subservient to them, the servile Polavieja.)

Oct. 5.—Placed in Montjuich Castle dungeon on arrival in Barcelona and the same day re-embarked for Manila. Friends and countrymen in London by cable made an unsuccessful effort for a Habeas Corpus writ at Singapore. On arrival in Manila was placed in Fort Santiago dungeon.

Dec. 3.—Charged with treason, sedition and forming illegal societies, the prosecution arguing that he was responsible for the deeds of those who read his writings.

Dec. 12.—Wrote poem “My Last Farewell” and concealed it in an alcohol cooking lamp, after appearing in a courtroom where the judges made no effort to check those who cried out for his death.

A Paris portrait of Rizal which appears on the 2-centavo stamped envelope. It is the only profile among his known portraits.

Dec. 15.—Wrote an address to insurgent Filipinos to lay down their arms because their insurrection was at that time hopeless. Address not made public but added to the charges against him.

Dec. 26.—Formally condemned to death by Spanish court martial.

Pi y Margall, who had been president of the Spanish Republic, pleaded with the Prime Minister for Rizal’s life, but the Queen Regent could not forgive his having referred in one of his writings to the murder by, and suicide of, her relative, Crown Prince Rudolph of Austria.

Dec. 30.—Married in Fort Santiago death cell to Josephine Bracken, Irish, the adopted daughter of a blind American who came to Dapitan for treatment.

Age 35 years, 6 months, 11 days. Shot on the Luneta, Manila, at 7:30 a. m., and buried in a secret grave in Paco Cemetery. (Entry of death made on back flyleaf of Paco Church Register, among suicides.)

1897, Jan.—Commemorated by Spanish Freemasons who dedicated a tablet to his memory, in their Grand Lodge hall in Madrid, as a martyr to Liberty.

1898, Aug.—Grave sought, immediately after the American capture of Manila, by Filipinos who placed over it, in Paco cemetery, a cross inscribed simply “December 30, 1896.” Since his death his name had never been spoken by his countrymen, but all references had been to “The Dead” (El Difunto).

Dec. 30.—Memorial services held by Filipinos, and American soldiers on duty carried their arms reversed.

1911, June 19.—Birth semi-centennial observed in all public schools by act of Philippine Legislature.

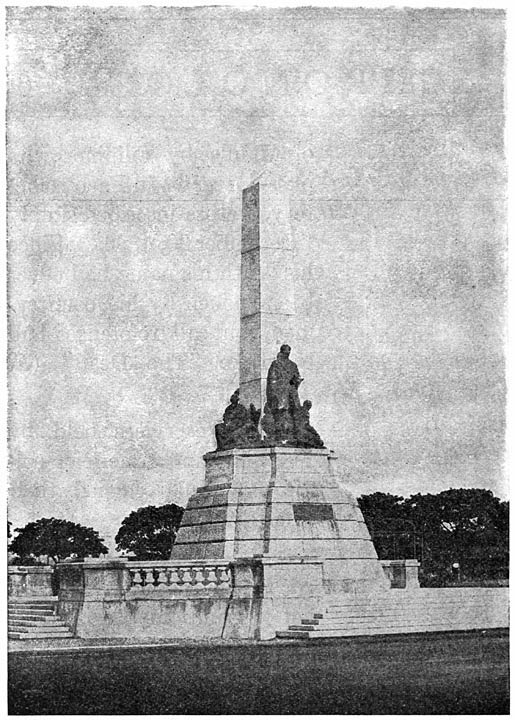

1912, Dec. 30.—Ashes transferred to the Rizal Mausoleum on the Luneta with impressive public ceremonies.

Rizal Mausoleum, Luneta, Manila. Here lies the body of José Rizal on the place of his execution, under a monument designed by the designer of the Swiss National Tell monument.

REFERENCES

A READING LIST

RIZAL, JOSÉ.—The Monkey and the Tortoise. A Tagalog tale told in English and illustrated by Rizal. Manila, 1912.

—Elias and Salome. An unpublished chapter from the original Noli Me Tangere manuscript.

—The Whole Truth. (La Verdad para Todos.) A defense of the Filipinos.

—By Telephone (Por Teléfono). A satire.

—The Philippines A Century Hence (Filipinas Dentro de Cien Años). A forecast of the future.

—The Indolence of the Filipino (La Indolencia de los Filipinos). An answer to criticism.

—My Last Thought and other Poems. Translations by Charles Derbyshire and A. P. Fergusson.

—Mariang Makiling. A folk tale.

(These titles are in the Noli Me Tangere Quarter-Centennial Series, edited by Austin Craig. Translations are by Charles Derbyshire.) Manila, 1912.

—An Eagle Flight: A Filipino Novel. Adapted from Noli Me Tangere, with a short sketch of Rizal’s life. Anonymous translator. New York, 1900.

Manuscript of Rizal’s Great Novel, now in the Philippine Library.

El Filibusterismo is the second part, or sequel, of the novel Noli me tangere. Rizal’s first novel told the Filipinos of their faults; this book warned Spain of the danger of losing her colony unless the colonial government became better. “Filibusterer” was the name given to Filipinos who wanted reforms in the government.

House where El Filibusterismo was begun. This sketch, made in pencil was enclosed in a letter from Los Baños to Prof. Blumentritt.

—Friars and Filipinos. An abridged translation of Noli Me Tangere by F.E. Gannett. New York, 1900.

—The Social Cancer. Charles Derbyshire’s translation of Noli Me Tangere. Manila and New York, 1912.

—The Reign of Greed. Charles Derbyshire’s translation of El Filibusterismo. Manila and New York, 1912.

BLUMENTRITT, F.—Life of José Rizal. Translated from the German by H.W. Bray. Singapore, 1898.

—Views of Doctor Rizal, the Filipino Scholar, upon Race Differences. Translated from the German by R.L. Packard. Popular Science Monthly, Vol. 61 (July, 1902), pages 222–229.

HALSTEAD, MURAT.—The Story of the Philippines. Pages 190–201 give a translation of Rizal’s “The Vision of Friar Rodriguez” (La Visión de Fray Rodriguez) by F.M. de Rivas. Chicago, 1898.

CLIFFORD, Sir HUGH.—The Story of José Rizal, the Filipino. In Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Vol. 172 (Nov., 1902), pages 620–638.

CRAIG, AUSTIN.—Readings from Rizal. A series of selections from Rizal’s novels, in volume 1 of “The Philippine Teacher.” Manila, 1905.

—The Rizal Story in Pictures. A series of twenty-one post cards with authentic illustrations and explanations. Manila, 1908.

—The Story of José Rizal, the Greatest Man of the Brown Race. Manila, 1909.

—Lineage, Life and Labors of José Rizal. Manila and Yonkers-on-Hudson, 1912.

—Particulars of the Philippines’ Pre-Spanish Past. Dr. Rizal’s “Ibn Batutu’s Tawalisi the Northern Part of the Philippines” appears on pages 20–22. Manila, 1916.

CRAIG-FEE.—Rizal, the Martyr-Hero of the Philippines. An imaginative account, expanding the known facts, for youthful readers. In “Philippine Education.” Manila, 1913.

BLAIR-ROBERTSON.—The Philippine Islands 1493–1898. Rizal’s annotations to Morga’s 1609 History of the Philippines appear among the notes in Vols. XV and XVI. Cleveland, Ohio, 1904.

Brief sketches of Rizal’s life and work may be found in every encyclopedia published since 1898, the modern histories of the Philippines have extended references to him and the numerous recent works on the Philippines all attempt estimates of his influence upon his countrymen.

Diploma of Merit won by José Rizal

In a literary competition in honor of Spain’s greatest writer, Cervantes, held in Manila in 1880, the Liceo Artistico-Literario offered a gold ring as first prize and the Economic Society of the Friends of the Country gave the winner a diploma of merit. Rizal’s allegory, “The Council of the Gods” was preferred by the judges, all Spaniards. But when the envelopes containing the contestants’ names were opened, there was objection to giving first prize to a Filipino when prominent Spaniards had taken part in the contest. Rizal says that he was hissed off the stage when he appeared in answer to the reading of his name. Manila newspapers of that period dared not speak of the incident openly but there were several veiled allusions to it. One writer sarcastically said that medical students should be forbidden to write poetry.

THE COUNCIL OF THE GODS

“We gods and goddesses, met on Mount Olympus, find that the greatest three authors in the world’s history are of equal merit. So in justice equal respect must be paid them. To Homer we award fame’s trumpet, to Vergil the lyre of glory, and to Cervantes the laurel wreath of immortal honor.”

To the Philippine Youth

“Hold high the brow serene,

O youth, where now you stand;

Let the bright sheen,

Of your grace be seen,

Fair hope of my Fatherland!”

Prize, and the first verse of the winning poem, won by Rizal at the age of 17 in a public competition open to “Indians and Mestizos”. By these two names, the Spaniard called, and divided, the Filipinos.

My Last Thought

“Farewell, beloved Fatherland, thou sunny clime of ours,

Pearl of the Orient Ocean, our lost Paradise!

For thee my life I give, nor mourn its saddened hours;

And were’t more bright, strewn less with thorns and more with flowers,

For thee I still would give it, a welcome sacrifice.”

The alcohol lamp in which Rizal hid the poem, called “My Last Thought,” which he wrote in the night after he learned that he was to die. The original poem, whose ink shows the effects of the alcohol, is now in the Philippine Library.

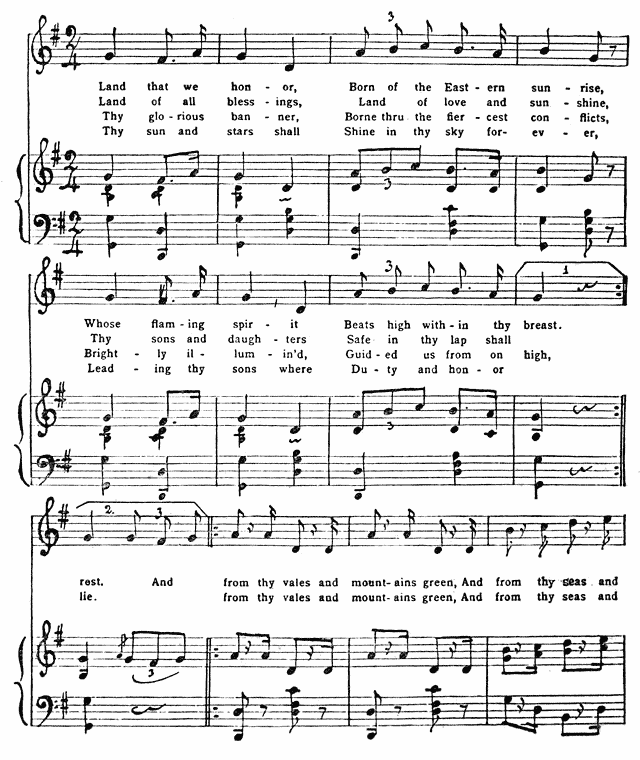

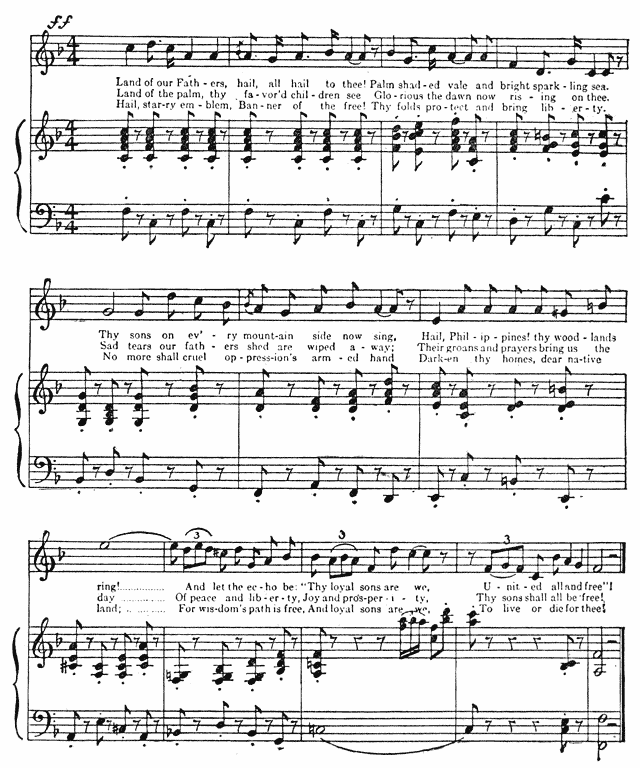

HAIL, PHILIPPINES!

Words by L. H. Theobald

Music arranged from the Toreador’s song in the opera “CARMEN”

Colophon

Availability

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org.

This eBook is produced by the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at www.pgdp.net.

Encoding

Revision History

- 2015-03-03 Started.

External References

This eBook contains external references. These links may not work for you.

Corrections

The following corrections have been applied to the text:

| Page | Source | Correction |

|---|---|---|

| 1, 12, 25, 27, 29, 30, 30, 33, 46, 57, 60, 62, 62, 69, 100, 104, 106, 108, 110, 114, 118, 120, 121, 121, 123, 125, 125 | [Not in source] | . |

| 11, 101 | Jose | José |