FROM JAPAN TO ENGLAND ACROSS AMERICA

From letters written en route to his friend Mariano Ponce and first published in Manuel Artigas’ Biblioteca Nacional Filipina, Manila, June, 1910.

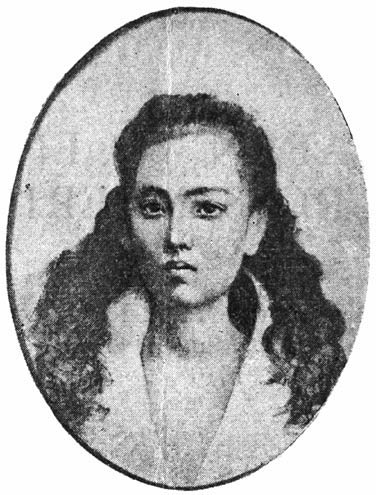

Crayon portrait of Rizal’s cousin, Leonore Rivera, to whom he was engaged. The drawing was made in 1882, just before he sailed for Spain. During his absence, his letters were kept from her and she was told that Rizal had forgotten her in the gay life of Europe. This was done because her mother’s advisers thought Rizal’s political ideas made him unsuitable for a husband. Leonore finally consented to the marriage urged upon her instead, and when too late, through Rizal’s return in 1887, learned how she had been deceived. She died not long afterwards, of a broken heart, it was said.

On February 28th, 1888, I arrived in Yokohama. A few moments after reaching the hotel, I received the card of the official in charge at the Spanish legation. I had not even had a chance to brush up when he called. He was very pleasant and offered to assist me in my work. He even invited me to live at the legation, and I accepted. If, at the bottom, there was a desire to watch me, I was not afraid to let them know all about myself. I lived at the legation a little over a month, and traveled in some of the nearby provinces of Japan. At times, I was alone; at others, with the Spanish official himself, or with the interpreter. While there, I learned to speak Japanese, and made a slight study of the Japanese theatre. After many offers of employment, which I refused, I sailed at last for America, about April 13th.

On the steamer, I met a half-Filipino family, the wife being a mestiza, the daughter of an Englishman named Jackson. They had with them a servant from Pangasinan. The son asked me if I knew “Richal,” the author of Noli Me Tangere. Smiling, I answered that I did; and, as he began to speak well of me, I had to make myself known and say that I was the author. The mother paid me compliments, too. I made the acquaintance of a Japanese who was going to Europe. He had been a prisoner for being a radical and editor of an independent newspaper. As the Japanese spoke only Japanese, I acted as interpreter for him until we arrived in London.

During this voyage I was not seasick.

I visited the larger cities of America, where I saw splendid buildings. The Americans have magnificent ideals. America is a homeland for the poor who are willing to work.

I traveled across America, and saw the majestic cascade of Niagara. I was in New York, the great city, but there everything is new. I went to see some relics of Washington, that great man whom I fear has not his equal in this century.

I embarked for Europe on the “City of Rome”, said to be the second largest steamer in the world. On board, a newspaper was published up to the end of the voyage.

I made the acquaintance of many people. They wondered at my taking about with me a foreigner who could not make himself understood. The Europeans and Americans were astonished to see how I got along with him. I could speak to every one in his own language and understand what he said.