CHAPTER VII.

WAYSIDE WORK.

The town of Trichinopoly, which for the next sixteen years was to be his new sphere, was the second capital of the Nabob of Arcot and his residence. It was here that in 1767 he consented to become chaplain to the English garrison on condition that at any time he might again give himself wholly to the mission.

Once more the air was filled with battle-cries, and Hyder Ali, the despot of Mysore, began to threaten the great provinces of Southern India whose rulers had made an alliance with the English for the common safety. A large army prepared to march against the invader and in one of the heathen temples at Trichinopoly, converted into a hospital, Schwartz preached to the troops, standing for a pulpit upon a heap of black polished stones. He then went on a missionary journey to see the brethren at Tranquebar. On the way he found plenty of opportunity for giving his Gospel message to processions and wayside pilgrims and especially at one place, Ammal-Savadi, where, attached to a palace, was a row of houses nearly a mile long built for the Brahmins. Here he gathered a large crowd unto whom he preached the Word of Life, expounding the parable of the Prodigal Son. One of the Brahmins, much impressed, applied to himself the character of the wandering son which caused Schwartz to exclaim: “O that they would arise and go to their Father!” After ten days with his old friends at Tranquebar, he returned, passing on his way a magnificent banyan tree, in the shade of which the merchants were busy in their booths. To them he spoke of the Supreme Being, the Fall, how Christ came to redeem us, and that now there is a way of salvation and a highway of holiness. They could not do otherwise than agree with his earnest reasoning. “It is so written,” they said, “but who can live thus? Who is able thus to eradicate his desires? We have it also on the palm leaves but it is impossible to keep it.” There appeared no active opposition to his declaration of the truth. He records as regards the way of salvation that he invariably and most justly represented it “by true repentance, faith in the Divine Saviour Jesus Christ and godliness springing from a true faith. Not a single heathen made the least disturbance, they listened in silence. Afterwards I addressed them separately and exhorted them to receive the saving doctrines of the Gospel.”

Nothing seemed to stir the heart of Schwartz more than the abject idolatry of the people. He never missed an opportunity of pointing out that their superstition was no good to them, it could neither help nor comfort them in their need. “We talked ourselves quite weary,” he writes, “with various heathen. When the catechist read to them our Lord’s warning against false prophets and said something in explanation, a Brahmin declared before all present: ‘It is the lust of the eyes and of pleasures that prevents us from embracing the truth.’”

As a result of the continued fight with Hyder Ali, Schwartz found on returning to Trichinopoly a number of sick and wounded soldiers glad to welcome him back again. He makes a note in his journal of several interesting facts with regard to his ministrations among these English soldiers in the hospital.

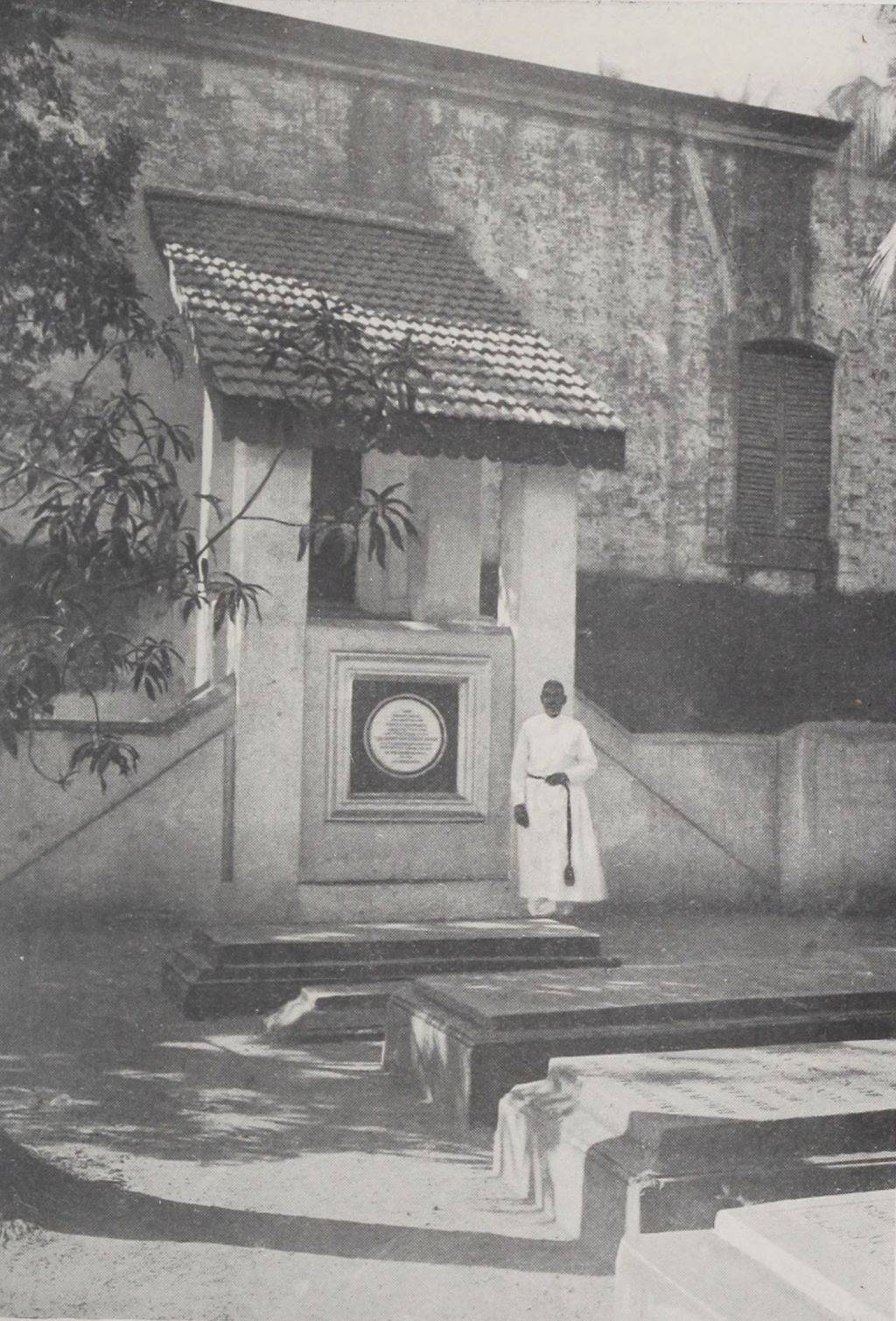

BISHOP HEBER PREACHED HIS LAST SERMON FROM THE STEPS

“Here I have often found,” he writes, “blessed traces of awakening grace. A soldier said he had been such thirty-two years. I asked him how long he had served Christ? He wept and replied, ‘Alas, I have not yet entered His service.’” “An officer who had previously discovered a great inclination to religion and entreated me to instruct him catechetically, just as I would an ignorant heathen, in which we had made a beginning, but were interrupted by the war, was brought in mortally wounded. He expressed a great desire for instruction. I accordingly visited him daily and explained to him the chief points in practical Christianity. After a few days he appeared to be something better. He could occasionally take the fresh air and his appetite returned. Under these circumstances he gradually yielded to indifference as to religion. He listened, indeed, but not with real earnestness. At length I said to him, ‘I see you are quite different. I fear you are deceiving yourself. Your wound is as mortal now as it was fourteen days ago. When you perceive that you are drawing near to your end you will be terrified to think that you have been so foolish as to allow worldly men to draw you off from the chief concern.’ He replied, ‘It is true, they have flattered me with the hope that I shall recover; but it is not so. I know that my wound is mortal.’ After this he became more earnest in prayer and meditation on the Word of God. Before his death I visited him and exhorted him to commit himself in faith into the hands of his Merciful Saviour. Speaking was painful to him, yet he said he hoped to obtain mercy, and thus he departed amid the exhortations and prayers of those around him.”

He went frequently to the river where the Brahmins used to assemble the people and read to them the history of Ram. On his way he met one of the Court officials, called the King’s Ahlikar, whose duty it was to go about the place and among the crowds and then to make a report to his Royal master of anything which he saw of an extraordinary nature.

“Tell the King,” said Schwartz, “that you saw me and that I declared to great and small that they ought to turn from vain idols to the living God, and that from my heart I wish the King would set others in this respect a good example.” “Good, good,” said he, “I will tell him so.”

There was something in the personality of Schwartz which greatly attracted the Brahmins, who were and still are very loth to discuss the Christian religion. But with this missionary at least they had no such reserve; indeed, they often presented themselves as seekers after truth, and quite frankly admitted the force of many arguments advanced against their idolatry to be reasonable. It must be considered that hitherto they had had little opportunity of judging the claims of Christianity, for in the case of the Europeans it was unhappily absent as any moral force, and as presented by the Roman Catholics it contained an element as idolatrous to their mind as their own. For the first time they had come into touch with a man who had a profound knowledge of their own position and had a friendly and sincere sympathy in meeting their difficulties and bringing light where they were in darkness. He met them as a friend and yet never spared their sinfulness, he never rebuffed them as beyond hope, he cheered them with a loving message of peace from One Who could save to the uttermost. These conversations are of the deepest interest; the difficulties they disclose have not changed and the answers which Schwartz gave are just as wise and applicable as if spoken to-day. His journal is rich in these incidents. A little hut of leaves of the palmyra tree at Ureius near the foot had been put up by him as a place of resort for quiet to which any inquirers were always welcome. One day a group of Brahmins came and he opened the conversation by asking them what was their creed and what it all meant when they taught the people.

“The eldest replied, ‘We teach that God is omnipresent and is to be found in everything.’

“‘It is true,’ I said, ‘God is present everywhere and to every one of his creatures but it does not follow from this that you are to adore and worship every creature. If you regard the heaven, earth, sun, and moon, as evidences of the power, wisdom, and goodness of God and as creatures that lead to the Creator you do well; but if you invoke the creature, you ascribe to it the glory which is due to God alone and fall into idolatry. Besides the creature is not perfect but only a frail image of the Almighty. Can an idol which is unable to see, speak, or move, adequately set forth to you the majesty, greatness, wisdom, and goodness of the living God?’

“They acknowledged that it could not. I next demanded of a Brahmin whether he did not perceive that the world was full of sin and that we should all be found guilty and how he might obtain forgiveness? He answered, ‘Through the mercy of God.’ ‘You say right,’ I resumed, ‘but you know that God is righteous and punishes the wicked, how then can a just God be gracious to such sinful creatures so as fully to pardon us and to make us blessed?’ Upon this I explained to them the doctrine of redemption through Jesus Christ and earnestly exhorted them to embrace it.

“In one of the pagodas at Puttur there resides a learned Pandaram who is generally friendly and does not seem entirely to reject instruction. We both seated ourselves on a bank of earth near a street. This brought together a concourse of inhabitants. The Pandaram said: ‘My chief question to you again and again has been this: How shall I arrive at a knowledge of God whom I cannot see?’ I replied, ‘It has often been stated to you that heaven and earth declare the glory of God. Reflect then attentively on the creation and you will soon be convinced that no other than an Almighty, All-wise and All-gracious Being produced it. This Creator we ought in justice to reverence and adore, but you render this honour to the creature and not to the Creator.’ ‘This,’ said he, ‘is all good but it does not satisfy me, this knowledge is not of the kind I seek.’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘do you desire to have a clearer and more perfect knowledge? God has in great goodness afforded it. He has taken compassion on ignorant man and given freely to him His word and true law, whenever He has revealed all the doctrines which are necessary to the attainment of everlasting happiness. He has made known to men, rebellious, corrupt, and lost, the Saviour of the world, as the restorer of forfeited blessedness and the way in which that salvation is to be attained. In short, all that can make us holy and happy is in this word of God made known to mankind. Read and meditate upon it with prayer to God, so will it become clear to you. Compare it also with your heathen instruction and the superiority of the Divine word will soon be discovered.’

“‘Still,’ said he, ‘this is not enough, for even if I read this I cannot rightly conceive the idea of what God is.’

“‘Well,’ I replied, ‘one thing is wanting to you, namely, experience. Lay your heathenism aside; follow the word of God in every point and pray to Him for light and power. Then I may assure you that you will say “Now I am like one who could not, from any description, understand the nature of honey but now I have tasted it and know what honey really is”.’”

Then as now too often the argument against Christianity is the inconsistency of those who profess to believe in it. This strikes a Mohammedan, for instance, very much, and while it is, of course, no logical excuse, he will make much of it to the detriment of the power of the Gospel. Schwartz met with this on every hand; Anglo-Indian Society was not at a very high moral water mark in the days of the Company, and it did not escape the criticism of those dark and watchful native eyes. There is an incident which illustrates the position at Trichinopoly in the year 1768.

“The Nabob’s second son,” writes Schwartz in his journal, “who is a genuine disciple of Mohammed, that is, inclined to cruelty, watches narrowly the lives of Europeans, and if he remarks anything wrong he generally gives it a malicious construction as if the Mohammedan doctrine rendered people better than the Christian. This young man observing some Europeans, entered into conversation with them. I was the interpreter. ‘It seems remarkable,’ said he, ‘to me that Christians are so inclined to card playing, dancing, and similar amusements which are contrary to the true law.’ One of them answered, ‘We think it no sin, but an innocent pastime.’ ‘Indeed,’ said he, ‘it is singular you do not consider it sin to spend your time in such amusements when even the heathen themselves declare it to be sinful. It is certainly wrong to pursue such things, though you are of opinion that there is nothing sinful in them. You,’ he continued, addressing one of the party, ‘are a cashier, if you do not know the value of money you inquire and inform yourself on the subject. Why then do you not examine into these things? The omitting such an examination is a sin also. Nay, if you do not know whether it is right or wrong and yet continue to play that is still a greater sin. I am sure Padre Schwartz would tell you at once that it is sinful, if you would but receive it.’ The cashier replied, ‘It is better to play a little, than to absorb all one’s thoughts on money.’ But the young Nabob answered him very discreetly on this point, ‘that we are not to justify one sin by another.’ So artful is he that he will accost and converse with a European during divine service and afterwards observe: ‘If the man had the least reverence for the worship of God he would not have allowed himself to be interrupted.’ On the 15th of this month,” continued Schwartz, “in the morning I had a conversation with him. He first asked how God was to be served and how we should pray to Him and censured us for not washing our hands and taking off our shoes before prayer. I answered that this was merely a bodily, outward act which was of no value in the sight of God—that His word requires pure hearts which abhor all and every sin and approach Him in humility and faith—we could then be assured that our prayer was acceptable to Him. One of those present asked, ‘From what must the heart be cleansed?’ I replied, ‘From self-love, from fleshly and worldly lusts which constitute, according to the first commandment, the real inward nature of idolatry.’ The Nabob’s son said, ‘This inward cleansing is very good but the outward is also necessary and God is pleased with it, even though the inward cleansing be not perfect.’ I replied, ‘Not so. You should rather say that God has pleasure in inward purity, though the hands be not washed immediately before prayer.’”

We have no means of knowing whether this young quibbler was in the end awakened to a sense of his own deficiencies. But we can judge by these conversations that in Schwartz he had a patient as well as a faithful listener who did not fail to show him the way of life and the only source of grace and truth.

On one of the occasions when he could hold conversations with the Nabob’s son over religious matters, Schwartz impressed upon him the law of brotherly love, even to enemies, which Christ enjoined on His disciples. The answer he received was a remarkable instance how in the poetical books of the Hindus the same principle of meekness towards enemies was laid down. “Of the behaviour of men in regard to meekness,” said he, “four kinds were mentioned of which he gave the following explanation: Schariat, Terikat, Marifat, Hakikat, are four ways which men go.” “A young man,” he said, “once asked a priest what he understood by these four ways? The priest desired him to go into the market and give a blow (or box on the ear) to each one he met. The young man did as the priest desired. He struck the first man who met him; now he was evil and returned like for like and struck him again. The second whom the young man met, was indeed wicked, and raised his hand to strike him in return, but changed his mind, and went away quietly. The third who was beaten was not wicked and did not threaten to return like for like, in that he thought the blow came from God. The fourth when he was beaten was full of love and kissed the hand that smote him. The first who when he was beaten struck again, is an emblem of Schariat, or the way of the world. The second felt wrath but overcame it and is an emblem of Terikat. The third endured the blow with patience and is an example of Marifat, or mature knowledge. The fourth who kissed the hand that smote him is an example of Hakikat, or inward union with God, in that he regarded all the injustice that was done to him as love on account of this union with God.”

Following the example of his Divine Master, Schwartz turned from the arguments and equivocations of the wise and prudent and looked with infinite compassion on the sincere seekers after good, those who were poor and simple, and were pitiful in their need and darkness. Can anything be more touching or expressive of the yearning of a loving heart than these words which Schwartz addressed to such?

“At length I said, as I often do to them, ‘Do not suppose that I reprove you out of scorn, no, you are my brethren, we are by creation the children of one common Father. It grieves us Christians that you have forsaken that almighty gracious Father and have turned to idols who cannot profit you. You know, because you have often heard, that a day of judgment is before us, when we must render up an account. Should you persist in remaining enemies to God and on that day hear with dismay the sentence of condemnation I fear you will accuse us Christians of not warning you with sufficient earnestness. Suffer yourselves then to be persuaded, since you see that He wants nothing of you but that you turn with us to God and be happy!’ They all declared that they were convinced of our sincere intentions and that they would speak further with us.”

His hands were full but his work was the very joy of his heart. One thought stirs him continually, the need of these poor heathen and the sufficiency of Christ for it all. He rejoices that in the midst of all his labours he has such a measure of good health and he has signs on every hand that he has not laboured in vain. “Affliction, both from without and from within, has not failed us but God has been our helper” is his testimony. He finds that the natives are not ready to show the same respect to his catechists as to Europeans, so here is opportunity for encouraging the weak and he stands by his native helpers like the strong good man he was. He thanks God for Europeans, military and civil, who have been led to make a stand for Christ, specially of one young visitor. “He visited me several evenings and acknowledged that he was stirred up to greater concern for his salvation. I testified my joy but observed that he was at present trusting to the sandy foundation of his own righteousness, from which he could derive neither rest nor power. He received all that I said in good part and began to read his New Testament better; that is with prayer. Shortly afterwards he was invited to a gay party but declined it, which had a good effect on others. He soon learned how the Gospel becomes saving and communicates to man more power unto salvation than any considerations derived merely from the law. He went boldly forth, and when many were displeased that a young man should speak so freely, he gladly bore the cross and his example has been a blessing to others.”