CHAPTER XVI.

THE MEMORY OF THE JUST.

By his last will and testament Schwartz left all he had to the mission. He had never married, and had, therefore, no family obligations to consider, but a hundred star pagodas, equal to about £43 in English currency at that time, he directed should be divided amongst his sister’s children. His two gold watches were to be sold and the proceeds given to the poor, thirty star pagodas were to go to his personal servant, and a few silver articles to his friend, Mr. Kohlhoff, as a token of his hearty love. But, apart from these trifling specific bequests, all his savings, together with such property as he had built with his own money, were devoted to the maintenance and support of the work he loved so well. His own personal needs had always been few, his life almost ascetic in its simplicity, so that he was able to put by the allowance from the Government as chaplain to the soldiers, and yet he was generous to the poor, and always ready to help young catechists in their studies. As we have seen, he consistently refused to accept any presents from either European or native rulers to whom he had been of service, and this in a time and place when fortunes were easily made and bribes excused redounds greatly to his credit. A more disinterested and faithful man never served his God and country better than he.

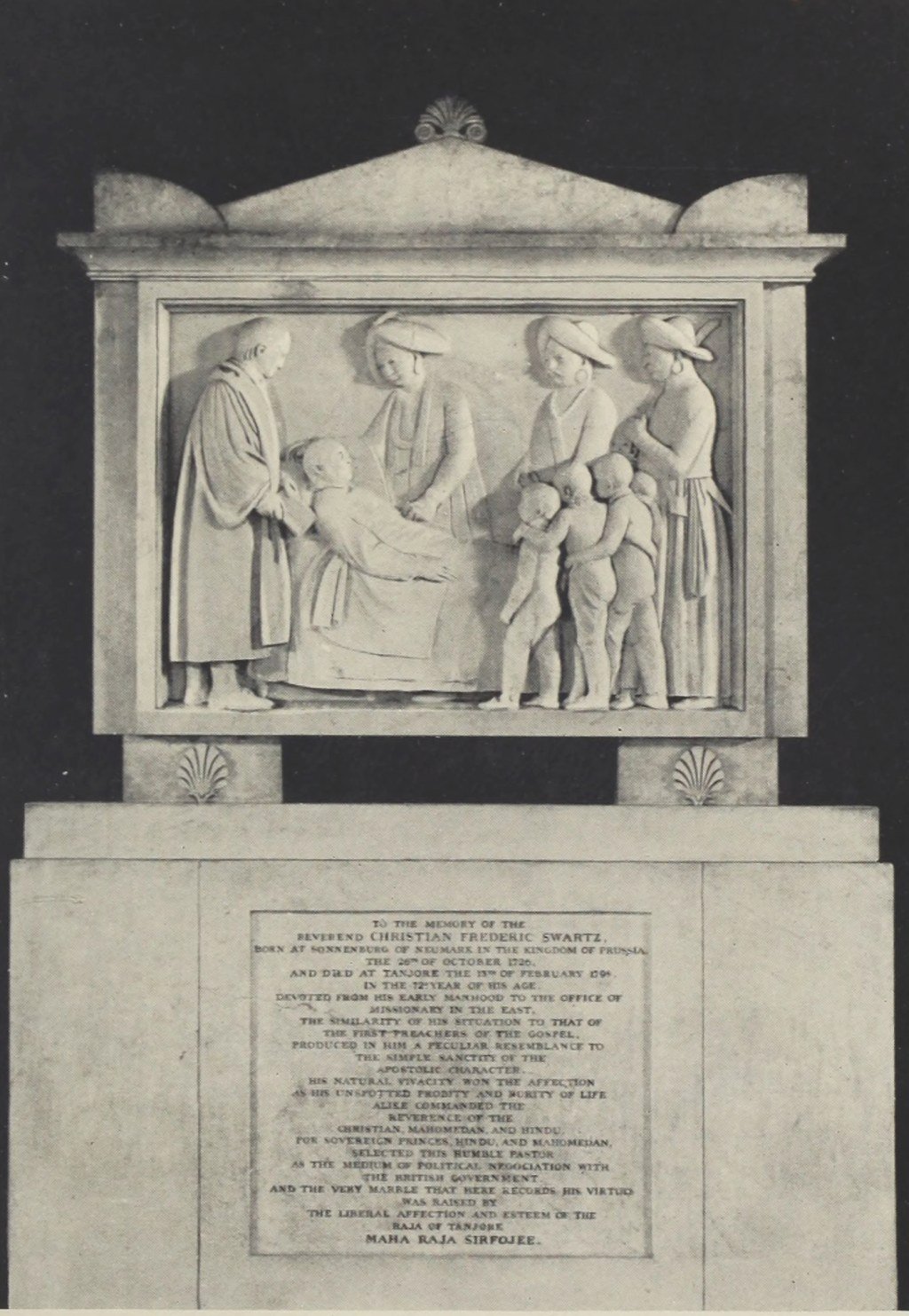

Serfogee Rajah took immediate steps towards the erection of a monument to commemorate the virtues of his beloved friend, and, writing to the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, begged them at his expense to have prepared and send a marble monument to his memory to be placed in the church, and near the pulpit where he preached. He closed his request with the words, “May you, honourable sirs, ever be enabled to send to this country such missionaries as are like the late Rev. Mr. Schwartz!” The work was entrusted to Flaxman, and comprised a beautiful group in bas relief representing the death-bed scene, where among some children and friends Serfogee, the Hindu prince, is holding the hand of his dying friend and receiving his blessing. The inscription is as follows:—

To the memory of the

Reverend Christian Frederic Schwartz,

born at Sonnenburg of Neumark, in the Kingdom of Prussia,

the 26th October, 1726,

and died at Tanjore, the 13th February, 1798,

in the seventy-second year of his age.

Devoted from his early manhood to the office of Missionary in the East, the similarity of his situation to that of the first preachers of the Gospel produced in him a similar resemblance to the simple sanctity of the Apostolic character. His natural vivacity won the affection, as his unspotted probity and purity of life alike commanded the reverence, of the Christian, Mohammedan and Hindu; for Sovereign princes, Hindu and Mohammedan, selected this humble pastor as the medium of political negotiation with the British Government, and the very marble which here records his virtues was raised by the liberal affection and esteem of the Rajah of Tanjore, Maha Raja Serfogee.

Still more expressive and touching are the lines which are inscribed on the granite stone which covers the grave of Schwartz, written and composed by Serfogee himself, a curiosity as being the only specimen of English verse ever attempted by a Hindu prince, at any rate up to that time. After the inscription of name and date, the following are the lines of poetry:

It ought to be placed on record that this grateful prince did not only honour his benefactor by an affectionate epitaph; he showed how much he revered his memory by building an orphanage and school and maintaining by his own generosity many poor children, he also gave every opportunity for his Christian servants to attend the services of their own Church. He never forgot his friend. When Dr. Buchanan visited the Rajah some time afterwards he was led up to where the portrait of Schwartz hung upon the wall of the palace. “He then discoursed,” says the visitor, “for a considerable time concerning ‘that good man,’ whom he ever revered as his father and guardian.”

Ten years later Bishop Middleton was also on a visit to Tanjore, and he also records the fact that “his highness dwelt with evident delight on the blessings which the heavenly lessons and virtues of Schwartz had shed upon him and his people,” and a similar expression of grateful regard occurred on the attendance of Bishop Heber at a durbar when the Rajah talked warmly about Schwartz, “his dear father.”

It is a source of regret that this Indian prince, with all his sincere affection for Schwartz and gratitude for his kindness to himself personally, should not have become a Christian. His attachment to the memory of the venerable missionary, his support and appreciation of the Christian work among his people after the death of Schwartz, is certainly much to his credit so long as it lasted, when we remember that he lived and died a Hindu surrounded by his Brahmins who would scarcely regard his sympathies in the direction of Christianity with any approval. Still, it is disappointing to record that up to the time of his sudden death in 1834 he never renounced his idolatries, and had not apparently received into the darkness of his heathen head the Light of the world.

As a matter of fact there seems good grounds for believing that the Rajah had in his later days so far forgotten the counsels of his venerable friend as to relax his kindly interest in the work he left behind. There is a note in Dr. Brown’s “History of Missions,” vol. i. p. 162, to this effect:

“We regret to find the following statement by Mr. Winstow, one of the American missionaries, who visited Tanjore in 1828: ‘The Rajah has become very unfriendly with the missionaries. He has yielded himself up to dissipation and given immense sums to the Brahmins, and to the temples to make himself a Brahmin. His only son is growing up in ignorance, making no steady application to any study of science.’ (American Missionary Herald, vol. xxv. p. 140.)”

In his case, at any rate, he could not excuse his neglect of salvation on the plea of lack of knowledge.

The directors of the East India Company were equally anxious to perpetuate the memory of one whom they held in conspicuous honour. What Serfogee had done at Tanjore they would do in the Church of St. Mary in Fort St. George, Madras. On 29th October, 1807, by the direction of the court a letter was written to say that a marble monument by Bacon was on its way to be erected there in memory of Mr. Schwartz. “As the most appropriate testimony of the deep sense we entertain of his transcendent merit, of his unwearied and disinterested labours to the cause of religion and piety, and the exercise of the finest and most exalted benevolence, also of his public services at Tanjore, where the influence of his name and character, through the unbounded confidence and veneration which they inspired, was for a long course of years productive of important benefits to the Company.” This beautiful monument, worthy of a sculptor of such eminence, represented also the death scene, with the exception that here Serfogee is absent, but one of the native children is embracing the hand of the dying missionary, his friend Kohlhoff supporting him by his arm, the figure of an angel bearing a cross is depicted above. There is also included below the group, emblems of the pastoral office—the Episcopal Crozier, the Gospel trumpet with the banners of the Cross, and an open Bible, upon which is inscribed the divine mandate of all missionary enterprise, “Go ye unto all the world and preach the gospel to every creature.”

Above is shown the ark of the covenant, and the whole is a most appropriate and artistic piece of work. The inscription was written by Mr. Huddleston, then one of the directors of the Company, and a very intimate and valued friend of Schwartz, and is in these words:

Sacred to the memory of

The Rev. Christian Frederic Schwartz,

whose life was one continued effort to imitate the example of

his Blessed Master.

Employed as a Protestant missionary from the Government of Denmark, and in the same character by the Society in England for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, he, during a period of fifty years, “went about doing good,” manifesting, in respect to himself, the most entire abstraction from temporal views, but embracing every opportunity of promoting both the temporal and eternal welfare of others. In him religion appeared not with a gloomy aspect or forbidding mien, but with a graceful form and placid dignity. Among the many fruits of his indefatigable labours was the Erection of the Church at Tanjore. The savings from a small salary were, for many years, devoted to this pious work, and the remainder of the expense supplied by individuals at his solicitation. The Christian Seminaries of Ramanadporam and in the Tinnevelly province were established by him.

Beloved and Honoured by Europeans,

he was, if possible, held in still deeper reverence by the Natives of this Country, of every degree and every sect; and their unbounded confidence in his integrity and truth was, on many occasions, rendered highly beneficial to the public Service.

The Poor and the Injured

looked up to him as an unfailing friend and advocate.

The Great and Powerful

concurred in yielding him the highest homage ever paid in this quarter of the globe to European virtue.

The Late Hyder Ali Cawn,

in the midst of a bloody and vindictive war with the Carnatic, sent orders to his officers “to permit the venerable father Schwartz to pass unmolested, and show him respect and kindness, for he is a holy man and means no harm to my Government”.

The Late Tuljajee, Rajah of Tanjore,

when on his death-bed, desired to entrust to his protecting care his adopted son, Serfogee, the present Rajah, with the administration of all the affairs of his country. On a spot of ground, granted to him by the same prince, two miles east of Tanjore, he built a house for his residence and made it

An Orphan Asylum.

Here the last twenty years of his life were spent in the Education and Religious Instruction of Children, particularly those of indigent parents, whom he gratuitously maintained and instructed; and here, on the 13th of February, 1798, surrounded by his infant flock and in the presence of several of his disconsolate brethren, entreating them to continue to make religion the first object of their care, and imploring with his last breath the divine blessing on their labours, he closed his truly Christian career in the 72nd year of his age.

The East India Company,

anxious to perpetuate the memory of such transcendent work,

and gratefully sensible of the public benefits which

resulted from his influence,

Caused this monument to be erected Ann. Dom., 1807.

The removal of Schwartz from his earthly sphere of labour was the heaviest blow which Christian missions had yet received. His name is one of the very first to be written in the bede roll of great Indian missionaries. The Church thanks God for their glorious service, and for the splendid spirit with which they did their Master’s will. But in the days when Schwartz closed his great career the missionary cause was still in its infancy, the pioneer example as regards our own country was the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, who had so nobly stood as foster parent to the Danish missionaries in Southern India, and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, who took over the work. But a crisis was rapidly approaching, for the enthusiasm which made Germany hitherto the fount and origin of missionary enterprise was cooling under the spell of a materialistic wave, a change which Schwartz did not fail to feel even at his distance from Europe, and lamented over. He had left behind him some faithful colleagues, in whose hands the work would be safe, but he foresaw difficulties which would arise when in their turn—and they were not young men—the responsibility of pastoral oversight and leading would fall into other hands.

The loss of Schwartz was felt all the more because he was such a remarkable personality, one of those men of whom it is fairly admitted that it is extremely difficult for another to take their place. Many men can do mighty works, but only the few can beget love and inspire, not only amongst their friends and converts, but in the hearts of worldly wise civilians, and the priests of pagan religions, a sincere and respectful confidence. It may be said in truth of Schwartz that in both these directions he had no equal in his day.

He was wont to bewail his own imperfections, and those of his letters which portray the inner reflections of his mind, show his humility, and how little he thought of himself. But we may take with confidence the judgment of his contemporaries, who had not only a personal knowledge of him, but saw with their own eyes the reality of the work he had done in India.

The Rev. Dr. Kerr, the senior chaplain at Fort St. George, who was careful to make the fullest inquiry, and to whom was entrusted the erection of the monument in St. Mary’s Church from the East India Company, paid him a high tribute in a sermon. Speaking of Schwartz, after following his honourable career in the East, he sums up his character in these words:

“Such a course of life, zealously pursued for a long series of years, and accompanied with that sweetly social disposition for which he was remarkable, gained him many friends and thousands of admirers. The blessing of the fatherless and the widow came upon him, and his hope was gladness. He rejoiced evermore in witnessing the divine effect of his honest endeavours, and if he did not make converts of all with whom he associated, he seldom failed to make friends of them with whom he happened to communicate. Not that he ever compromised a paramount duty from any false politeness or deference to superior station; for he decidedly and openly declared the condemnation of all who boldly and openly set gospel rules at defiance, as often as an opportunity for the purpose occurred. His reproof, however, was tempered with so much good nature, the desire of doing good to the offenders was so obviously his intention, that he seldom provoked the smallest ill-will by the strong but fatherly remonstrance which irreligious conversation and conduct frequently drew from him. Indeed, he seemed peculiarly gifted by divine providence with a happy manner, which enabled him to turn almost every occurrence, whether great or trivial, to the praise and glory of God.”

With reference to his services as a peace mediator between the Government and Hyder Ali, and in other similar instances when he was able to assist in the better government and development of the people, Dr. Kerr says:

“Amidst such great public undertakings and the high degree of consideration attached by all ranks of people in this country to Mr. Schwartz’s character, every road to the gratification of ambition and avarice was completely open to him. Courted by the prince of the country in which he resided, reverenced almost to adoration by the people at large, confidentially employed by the English Government in objects of the first political importance—to his honour it must be recorded, that he continued to value those things only as they appeared likely to prove subservient to his missionary work, as they made funds to assist him with building of his churches or the establishment of his schools over the country. With the single eye of the Gospel, he looked only to the effusion of divine truth, and the glad tidings of salvation through faith in Jesus Christ. The same principle which raised him in the public estimation, he continued to cherish in every stage of his devotion; untarnished by the venality and corruption which from various quarters it is well known assailed his virtue, he continued his missionary life carrying his cross and following the steps of his Divine Master to the end of his earthly being.”

Only three days before his own sudden death, Bishop Heber wrote an estimation of Schwartz, which is all the more valuable because it contains a frank admission of a mistaken impression he had previously formed concerning one side of his character.

“Of Schwartz and his fifty years’ labour among the heathen, the extraordinary influence and popularity which he acquired, both with Mussulmans, Hindus, and contesting European Governments, I need give you no account, except that my idea of him has been raised since I came in the South of India. I used to suspect that, with many admirable qualities, there was too great a mixture of intrigue in his character; that he was too much of a political prophet, and that the veneration which the heathen paid, and still pay, him, and which indeed almost regards him as a superior being, putting crowns and burning lights before his statue, was purchased by some unwarrantable compromise with their prejudices. I find I was quite mistaken. He was really one of the most active and fearless, as he was one of the most successful missionaries who have appeared since the apostles. To say that he was disinterested in regard to money is nothing; he was perfectly regardless of power, and renown never seemed to affect him, even so far as to induce an outward show of humility. His temper was perfectly simple, open, and cheerful; and in his political negotiations (employments which he never sought for, but which fell in his way) he never pretended to impartiality, but acted as the avowed, though certainly the successful and judicious agent of the orphan prince entrusted to his care, and from attempting whose conversion to Christianity he seems to have abstained from a feeling of honour.”

With respect to this closing remark about Serfogee, it is open to question whether the venerable missionary would have quite appreciated the compliment the Bishop pays him. It is always a cause for regret that this Indian prince, the object of so much solicitude on the part of Schwartz, should, after all, have died a pagan. But the fact of his not having died a Christian was scarcely due to any lack of pains taken by Schwartz towards his conversion, and it is still less likely that he would have avoided pressing upon him the claims of religion from a delicate sense of honour as his guardian. The evidence is all the other way, not only as regards Serfogee, but also the old Rajah Tuljajee, who was unhappily very far from being a Christian. In the case of the former the many letters, such as a Christian father would write to a son, from which some quotations have already been given, show that, though the gospel was continually impressed upon the attention of this young prince, he clung to his idolatries in spite of these earnest appeals, backed up, as they were, by a sincere personal affection on both sides. As regards the old Rajah, it was stated by Mr. Huddleston, who knew him well, that at one time he was fully convinced of the truths of the Christian religion, and was on the point of making a public avowal of it, but the harsh and unjust treatment he received from the Madras Government, which, of course, being European, had the reputation of being Christian, entirely turned him against the faith. One might imagine a mind half made up being thus affected, but, whether this held him back or not, we know how much he was under the domination of the Brahmins, and how pathetically he used to address Schwartz as “his padre.” The real reason for this sad condition spiritually was not only his attachment to the gods of his fathers, but his love of those sins which in time broke up his health and ruined his power.

Bishop Wilson of Calcutta in 1839, in giving his charge to his clergy, speaks in strong terms of recommendation of Schwartz, and in doing so gives some very interesting personal touches of his daily life.

“Permit me again to recommend the example of this eminent missionary. The biography of such a man is a study, as the artists speak. I have stood on Schwartz’s grave, I have visited his house, I have been in the room in which he died; I have seen his garden, his burial ground, and his mission schools. I have preached twice in his church. Never can I bless God enough for the honour of being permitted to speak of the unsearchable riches of Christ in this seat of the missionary’s labours. The venerable Kohlhoff was under him thirty-five years. He never knew him angry or indignant, except when any servants of the Lord were acting inconsistently or timidly—then he was all on fire. Once Sattianaden threw difficulties in undertaking a journey. Schwartz was much displeased and dispatched him instantly, with a sharp rebuke for dishonouring the high calling of Christ. His strength for labour was wonderful: five duties he performed every Sunday, one of them being the whole English morning service. He preached twenty or thirty minutes, and was very affectionate in his manner. He read constantly his Hebrew Bible and his Greek Testament. Every day he assembled his catechists and native priests to early prayers, and then sent them out, ‘You go there,’ ‘You visit such a circle,’ ‘You see how such and such families are going on.’ They returned about four, and reported their proceedings. He went himself to the schools, families, residents’ abodes, came in about one and remained at home studying or writing till four, when the catechists returned. He then took them with him, and seated himself in the mission churchyard or in his house, according to the season, and invited the heathen to converse and hear him read the scriptures. He was mild, but very authoritative; very acute also in answering their objections, and never allowed himself to be embarrassed. In the evening he called for his moonshee, and heard him read the Persian poets or historians, hoping particularly to relieve his spirits.

“He always inspired respect, no one dared to trifle with him. He had a good deal of policy and great sagacity on emergencies. His influence was supreme; his word law; his example and conduct consistent, frank and benignant, but with a firmness and almost sternness of purpose which kept all around him in implicit subjection. Mr. Kohlhoff’s strongest impression is of the authority he had acquired—no one dared or dreamt of opposing his various missions. He was master of everything and everybody. He, the father, and all the other missionaries, catechists, children, his family. Schwartz was, in short, father, priest, and judge. He was accustomed to say, ‘Will you prefer my punishment or the Rajah’s?’ ‘Oh, Padre, yours!’ The word was no sooner said than the sentence was awarded. In the science of governing mankind and in habits of business he must have resembled Wesley.

“As Mr. Kohlhoff sat by me at dinner, I asked him as to Schwartz’s general habits. He told me that he rose at five, breakfasted at six or seven, on a basin of tea made in an open jug, with hot water poured on it, and some bread cut into it. One half was for himself, the other for Kohlhoff. The meal lasted not five minutes. He dined on broth and curry very much as the natives. He never touched wine, except one glass on a Sunday. What was sometimes sent to him was reserved for the sick. His temperance was extraordinary, habitual, and enjoined on his catechists and brethren. He supped at eight, and after reading a chapter in the Hebrew Bible in private, and his own devotions, retired to rest about ten.”

In making a final estimate of Schwartz, gathering from the elements of evidence before us some means of judging his character, one cannot help feeling that he stood midway between the missionaries who preceded him and those who were to succeed him. The old order was soon to change. For many years the Danish Mission, brave pioneers struggling against many difficulties, had represented, not unworthily, the cause of Christianity in India. They were under disadvantages, limited in the area of their work by the political turmoil of the time, and also a little straitened in themselves. It is not to be expected that these early confessors of the faith could exercise the same judgment and fertility of resource which are the characteristics of the modern missionary. Their training at Halle was thorough enough, they held a sound theology, exercised a simple faith, with great diligence they acquired the Tamil and other languages necessary for their work, and they had a burning zeal for the salvation of the heathen. But they had no missionary literature to lead and instruct them, and, until Schultze came back to Halle, they had no experienced missionary to explain the nature of their work, and how to meet its difficulties. They also lacked that invaluable element of supervision and control which a Committee at the back of the workers affords at home, and which, though not without some disadvantages for which the frailty of human judgment is responsible, is acknowledged to be a strength to missionary enterprise. To a certain extent every man, and they were few, was a law unto himself. We are not forgetful of the fact that in the days of Ziegenbalg, his end was hastened by the arrogance of a missionary board at Copenhagen, under the domination of a self-opinionated tyrant, and that his able coadjutor Gründler also died of a broken heart from the same cause. But until the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge took over the workers, not only providing the sinews of war, but the still more effective counsel and prayer, they went on their way, fighting their battles, bearing their burdens, sometimes making their blunders, doing the best they could on the spot according to their realization of the immediate need. Even when Schwartz came upon the scene the simplicity and independence of the work as a Lutheran Evangelical mission was still maintained. One of the leading missionaries of to-day describes the position of the work in those old days in the following words:

“The missionaries themselves used to confirm and meet together for ordinations. The catechists used to baptize. Each congregation was independent, and ruled by its own missionary, although the missionaries would occasionally meet, as it were, in synod, and were in the habit of accepting guidance of any more prominent men, as, for example, of Schwartz, whom his brother missionaries always regarded as their spiritual father, and created into a quasi-bishop. Each missionary in local affairs was assisted by his catechists, who, under his presidency, formed a sort of disciplinary council, the decisions of which in various matters brought before them were usually confirmed by the civil power. The missionary was, in fact, regarded as the head of the community, in the same principle as native headmen were recognized, and was permitted to fine, flog, and otherwise punish offenders belonging to his community.”

It is not surprising that under this rather complex system of self-government, without lines of direct communication with England, Denmark, and Germany, a born administrator like Schwartz should have been looked up to with reverence and confidence. For he had the faculty of managing men with cheerfulness, and yet, as one had said of him, Schwartz commanded instant respect to his wishes, and made others feel their inferiority without any sense of fear. He had a personal charm, the power of exercising a powerful influence which inspired confidence, even with those natives who were ready to distrust everything European. He never lost touch with his people. One who knew him well in his relation to others reveals the secret of his great influence. “They saw,” he says, “other Europeans in succession lift themselves from obscurity and humble stations to affluence, rank and power, then disappear and others take their places, but none taking any interest in their welfare or making use of them except as a means of accomplishing their own aggrandizement, but Schwartz remained with them. In him they always saw the same unaspiring meekness, and found in him the same kind and disinterested friend. What could the natives of India among whom he lived conclude respecting such a man, but that which they did conclude, and which was a common observation among them when he was spoken of, namely, that he was unlike and superior to all other men!”

His very abilities and influence drew him within the dangerous zone of political affairs, and the fact that he stood so well with the powers that were the representatives of the British Government, might well have corrupted a man of less principle and sincerity. It may be said of him that he sat at the tables of rich men and talked on equal terms with the ambitious spirits of his time, but he kept his piety and simplicity through it all. They trusted his sagacity and leaned on his judgment in difficult situations, but they knew he was not to be bribed, and that he kept a clean hand. He was a scholar, and had a good knowledge of the classics, of German literature; he was also master of Hebrew, Tamil, Persian, Hindustani, Mahratta, and the Indo-Portuguese languages. There is no doubt that his linguistic powers were very helpful to him, as we have seen, they so often enabled him to get past the crafty Brahmins, and converse with the Rajah or the Pariah alike in their own tongue about the truths of Christianity.

While he promoted the growth of a native ministry and took great pains to train his catechists to a point of efficiency, he was not disposed to believe that India could ever dispense with European missionaries, who carried with them a weight of influence and respect which a native, however worthy, could not successfully obtain. At the same time he foresaw the importance and necessity of a native ministry under the jurisdiction of English leaders. This was shown in the ordination, by the rites of the Lutheran Church, of Sattianaden, who lived to a ripe old age, and was eminently useful in the work, and whose office as minister was cordially sanctioned by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. It is a fact sometimes hardly appreciated that a great part of almost every day was spent by Schwartz in training his catechists for the work of the ministry. There existed then no colleges to undertake this important duty, and the remote possibility that one day in India native clergy would hold their degrees from Oxford and Cambridge never entered into his wildest dreams. He was content and happy to do his part, and in doing this so faithfully he was preparing the way for the wonderful developments in the service of natives which should come in the future.

As a matter of fact, although there was a growing appreciation of the value of utilising native converts as catechists and helpers in the days following Schwartz, there appears to have been a corresponding reluctance to ordain them, save in exceptional cases, to the work of the ministry. The day of a native clergy dawned slowly. We have it on record that, so far nearer our present time as 1851, “although there were over 493 catechists and preachers there were under all the societies at work in India only twenty-one ordained native pastors.”

The extreme care and thoroughness of Schwartz in his training of a native agency was justified, and followed by the higher educational and intellectual preparation set on foot by the wise policy of the missionary societies. However it may answer elsewhere, it was not sufficient for work in India that the native should go forth with the simple equipment of an earnest heart and the Gospel message. Dr. Richter, in his invaluable “History of Missions,” puts the case clearly enough when he says:

“The man who attempted a discussion with either a Hindu or a Mohammedan at a mela or in the bazaar was as good as done for if his intellectual equipments were not equal or superior to that of his adversary; and such an equipment means not only a thorough knowledge of the Scriptures, but also an intimate acquaintance with the sacred literature of his opponents, when possible in the original languages, and sufficient theological and dialectic training to measure the distance against their system of religion. Further, it lay in the very nature of things that converts from high castes, who had only found the pearl of great price after long and sore conflict, should themselves burn with desire to commend this great treasure to their fellow-countrymen, and that as educated men they not only possessed the ability to profit by, but likewise might equitably claim a thorough theological training.”

In the case of a high caste Brahmin convert, we can easily see that the equipment as regards knowledge of his old creed is ready-made, but with a lower caste, say a Pariah, it would be obviously almost as difficult to acquire as with a European missionary. The question is one of great difficulty, and involves issues which affect the true and effective preparation of the western, as well as the eastern worker in India.

No one can, however, read the letters and journals of Schwartz without recognizing that he solved the problem. A trained mind, an unwavering faith in God, a complete mastery of Brahmin literature, a still better knowledge of his Bible, the engaging art of winning the hearts of his hearers, a never flinching denunciation of idolatry and sin, a willingness to listen and to sympathize, an absolute fidelity to the Christian doctrine, a yearning love for the souls of men, a meek yet passionate love for the Saviour, these were the constituents of his character and service. Is it any wonder that they loved and trusted him? They gave him many titles of respect and honour, some very tender, but when with reverence they called him “The Christian,” that name was the best of all.