“Tom!”

No answer.

“TOM!”

No answer.

“What’s gone with that boy, I wonder? You TOM!”

No answer.

The old lady pulled her spectacles down and looked over them about the room; then she put them up and looked out under them. She seldom or never looked through them for so small a thing as a boy; they were her state pair, the pride of her heart, and were built for “style,” not service—she could have seen through a pair of stove-lids just as well. She looked perplexed for a moment, and then said, not fiercely, but still loud enough for the furniture to hear:

“Well, I lay if I get hold of you I’ll—”

She did not finish, for by this time she was bending down and punching under the bed with the broom, and so she needed breath to punctuate the punches with. She resurrected nothing but the cat.

“I never did see the beat of that boy!”

She went to the open door and stood in it and looked out among the tomato vines and “jimpson” weeds that constituted the garden. No Tom. So she lifted up her voice at an angle calculated for distance and shouted:

“Y-o-u-u TOM!”

There was a slight noise behind her and she turned just in time to seize a small boy by the slack of his roundabout and arrest his flight.

“There! I might ’a’ thought of that closet. What you been doing in there?”

“Nothing.”

“Nothing! Look at your hands. And look at your mouth. What is that truck?”

“I don’t know, aunt.”

“Well, I know. It’s jam—that’s what it is. Forty times I’ve said if you didn’t let that jam alone I’d skin you. Hand me that switch.”

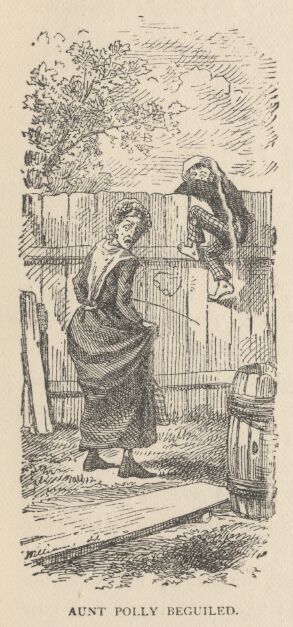

The switch hovered in the air—the peril was desperate—

“My! Look behind you, aunt!”

The old lady whirled round, and snatched her skirts out of danger. The lad fled on the instant, scrambled up the high board-fence, and disappeared over it.

His aunt Polly stood surprised a moment, and then broke into a gentle laugh.

“Hang the boy, can’t I never learn anything? Ain’t he played me tricks enough like that for me to be looking out for him by this time? But old fools is the biggest fools there is. Can’t learn an old dog new tricks, as the saying is. But my goodness, he never plays them alike, two days, and how is a body to know what’s coming? He ’pears to know just how long he can torment me before I get my dander up, and he knows if he can make out to put me off for a minute or make me laugh, it’s all down again and I can’t hit him a lick. I ain’t doing my duty by that boy, and that’s the Lord’s truth, goodness knows. Spare the rod and spile the child, as the Good Book says. I’m a laying up sin and suffering for us both, I know. He’s full of the Old Scratch, but laws-a-me! he’s my own dead sister’s boy, poor thing, and I ain’t got the heart to lash him, somehow. Every time I let him off, my conscience does hurt me so, and every time I hit him my old heart most breaks. Well-a-well, man that is born of woman is of few days and full of trouble, as the Scripture says, and I reckon it’s so. He’ll play hookey this evening,[*] and I’ll just be obleeged to make him work, tomorrow, to punish him. It’s mighty hard to make him work Saturdays, when all the boys is having holiday, but he hates work more than he hates anything else, and I’ve got to do some of my duty by him, or I’ll be the ruination of the child.”

[*] Southwestern for “afternoon”

Tom did play hookey, and he had a very good time. He got back home barely in season to help Jim, the small colored boy, saw next-day’s wood and split the kindlings before supper—at least he was there in time to tell his adventures to Jim while Jim did three-fourths of the work. Tom’s younger brother (or rather half-brother) Sid was already through with his part of the work (picking up chips), for he was a quiet boy, and had no adventurous, trouble-some ways.

While Tom was eating his supper, and stealing sugar as opportunity offered, Aunt Polly asked him questions that were full of guile, and very deep—for she wanted to trap him into damaging revealments. Like many other simple-hearted souls, it was her pet vanity to believe she was endowed with a talent for dark and mysterious diplomacy, and she loved to contemplate her most transparent devices as marvels of low cunning. Said she:

“Tom, it was middling warm in school, warn’t it?”

“Yes’m.”

“Powerful warm, warn’t it?”

“Yes’m.”

“Didn’t you want to go in a-swimming, Tom?”

A bit of a scare shot through Tom—a touch of uncomfortable suspicion. He searched Aunt Polly’s face, but it told him nothing. So he said:

“No’m—well, not very much.”

The old lady reached out her hand and felt Tom’s shirt, and said:

“But you ain’t too warm now, though.” And it flattered her to reflect that she had discovered that the shirt was dry without anybody knowing that that was what she had in her mind. But in spite of her, Tom knew where the wind lay, now. So he forestalled what might be the next move:

“Some of us pumped on our heads—mine’s damp yet. See?”

Aunt Polly was vexed to think she had overlooked that bit of circumstantial evidence, and missed a trick. Then she had a new inspiration:

“Tom, you didn’t have to undo your shirt collar where I sewed it, to pump on your head, did you? Unbutton your jacket!”

The trouble vanished out of Tom’s face. He opened his jacket. His shirt collar was securely sewed.

“Bother! Well, go ’long with you. I’d made sure you’d played hookey and been a-swimming. But I forgive ye, Tom. I reckon you’re a kind of a singed cat, as the saying is—better’n you look. This time.”

She was half sorry her sagacity had miscarried, and half glad that Tom had stumbled into obedient conduct for once.

But Sidney said:

“Well, now, if I didn’t think you sewed his collar with white thread, but it’s black.”

“Why, I did sew it with white! Tom!”

But Tom did not wait for the rest. As he went out at the door he said:

“Siddy, I’ll lick you for that.”

In a safe place Tom examined two large needles which were thrust into the lapels of his jacket, and had thread bound about them—one needle carried white thread and the other black. He said:

“She’d never noticed if it hadn’t been for Sid. Confound it! sometimes she sews it with white, and sometimes she sews it with black. I wish to gee-miny she’d stick to one or t’other—I can’t keep the run of ’em. But I bet you I’ll lam Sid for that. I’ll learn him!”

He was not the Model Boy of the village. He knew the model boy very well though—and loathed him.

Within two minutes, or even less, he had forgotten all his troubles. Not because his troubles were one whit less heavy and bitter to him than a man’s are to a man, but because a new and powerful interest bore them down and drove them out of his mind for the time—just as men’s misfortunes are forgotten in the excitement of new enterprises. This new interest was a valued novelty in whistling, which he had just acquired from a negro, and he was suffering to practise it undisturbed. It consisted in a peculiar bird-like turn, a sort of liquid warble, produced by touching the tongue to the roof of the mouth at short intervals in the midst of the music—the reader probably remembers how to do it, if he has ever been a boy. Diligence and attention soon gave him the knack of it, and he strode down the street with his mouth full of harmony and his soul full of gratitude. He felt much as an astronomer feels who has discovered a new planet—no doubt, as far as strong, deep, unalloyed pleasure is concerned, the advantage was with the boy, not the astronomer.

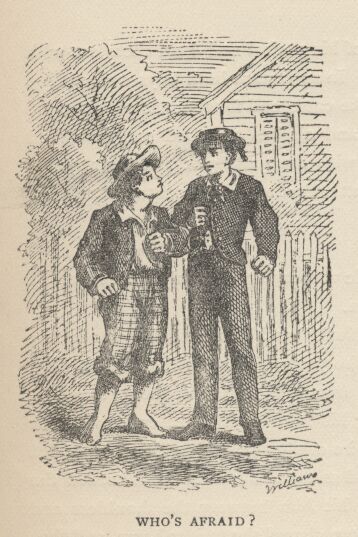

The summer evenings were long. It was not dark, yet. Presently Tom checked his whistle. A stranger was before him—a boy a shade larger than himself. A new-comer of any age or either sex was an impressive curiosity in the poor little shabby village of St. Petersburg. This boy was well dressed, too—well dressed on a week-day. This was simply astounding. His cap was a dainty thing, his close-buttoned blue cloth roundabout was new and natty, and so were his pantaloons. He had shoes on—and it was only Friday. He even wore a necktie, a bright bit of ribbon. He had a citified air about him that ate into Tom’s vitals. The more Tom stared at the splendid marvel, the higher he turned up his nose at his finery and the shabbier and shabbier his own outfit seemed to him to grow. Neither boy spoke. If one moved, the other moved—but only sidewise, in a circle; they kept face to face and eye to eye all the time. Finally Tom said:

“I can lick you!”

“I’d like to see you try it.”

“Well, I can do it.”

“No you can’t, either.”

“Yes I can.”

“No you can’t.”

“I can.”

“You can’t.”

“Can!”

“Can’t!”

An uncomfortable pause. Then Tom said:

“What’s your name?”

“’Tisn’t any of your business, maybe.”

“Well I ’low I’ll make it my business.”

“Well why don’t you?”

“If you say much, I will.”

“Much—much—much. There now.”

“Oh, you think you’re mighty smart, don’t you? I could lick you with one hand tied behind me, if I wanted to.”

“Well why don’t you do it? You say you can do it.”

“Well I will, if you fool with me.”

“Oh yes—I’ve seen whole families in the same fix.”

“Smarty! You think you’re some, now, don’t you? Oh, what a hat!”

“You can lump that hat if you don’t like it. I dare you to knock it off—and anybody that’ll take a dare will suck eggs.”

“You’re a liar!”

“You’re another.”

“You’re a fighting liar and dasn’t take it up.”

“Aw—take a walk!”

“Say—if you give me much more of your sass I’ll take and bounce a rock off’n your head.”

“Oh, of course you will.”

“Well I will.”

“Well why don’t you do it then? What do you keep saying you will for? Why don’t you do it? It’s because you’re afraid.”

“I ain’t afraid.”

“You are.”

“I ain’t.”

“You are.”

Another pause, and more eying and sidling around each other. Presently they were shoulder to shoulder. Tom said:

“Get away from here!”

“Go away yourself!”

“I won’t.”

“I won’t either.”

So they stood, each with a foot placed at an angle as a brace, and both shoving with might and main, and glowering at each other with hate. But neither could get an advantage. After struggling till both were hot and flushed, each relaxed his strain with watchful caution, and Tom said:

“You’re a coward and a pup. I’ll tell my big brother on you, and he can thrash you with his little finger, and I’ll make him do it, too.”

“What do I care for your big brother? I’ve got a brother that’s bigger than he is—and what’s more, he can throw him over that fence, too.” [Both brothers were imaginary.]

“That’s a lie.”

“Your saying so don’t make it so.”

Tom drew a line in the dust with his big toe, and said:

“I dare you to step over that, and I’ll lick you till you can’t stand up. Anybody that’ll take a dare will steal sheep.”

The new boy stepped over promptly, and said:

“Now you said you’d do it, now let’s see you do it.”

“Don’t you crowd me now; you better look out.”

“Well, you said you’d do it—why don’t you do it?”

“By jingo! for two cents I will do it.”

The new boy took two broad coppers out of his pocket and held them out with derision. Tom struck them to the ground. In an instant both boys were rolling and tumbling in the dirt, gripped together like cats; and for the space of a minute they tugged and tore at each other’s hair and clothes, punched and scratched each other’s nose, and covered themselves with dust and glory. Presently the confusion took form, and through the fog of battle Tom appeared, seated astride the new boy, and pounding him with his fists. “Holler ’nuff!” said he.

The boy only struggled to free himself. He was crying—mainly from rage.

“Holler ’nuff!”—and the pounding went on.

At last the stranger got out a smothered “’Nuff!” and Tom let him up and said:

“Now that’ll learn you. Better look out who you’re fooling with next time.”

The new boy went off brushing the dust from his clothes, sobbing, snuffling, and occasionally looking back and shaking his head and threatening what he would do to Tom the “next time he caught him out.” To which Tom responded with jeers, and started off in high feather, and as soon as his back was turned the new boy snatched up a stone, threw it and hit him between the shoulders and then turned tail and ran like an antelope. Tom chased the traitor home, and thus found out where he lived. He then held a position at the gate for some time, daring the enemy to come outside, but the enemy only made faces at him through the window and declined. At last the enemy’s mother appeared, and called Tom a bad, vicious, vulgar child, and ordered him away. So he went away; but he said he “’lowed” to “lay” for that boy.

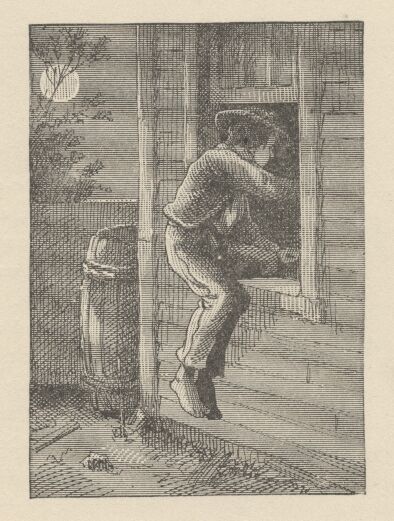

He got home pretty late that night, and when he climbed cautiously in at the window, he uncovered an ambuscade, in the person of his aunt; and when she saw the state his clothes were in her resolution to turn his Saturday holiday into captivity at hard labor became adamantine in its firmness.