IN AMERIKEY

San Francisco, night, 21st

“Good-bye, Mr. Belgic!”

I delight in personifying everything as a gentleman.

What does it mean under the sun! Kitsune ni tsukamareta wa! Evil fox, I suppose, got hold of me. “Gentlemen, is this real Amerikey?” I exclaimed.

Oya, ma, my Meriken dream was a complete failure.

Did I ever fancy any sky-invading dragon of smoke in my own America?

The smoke stifled me.

Why did I lock up my perfume bottle in my trunk?

I hardly endured the smell from the wagons at the wharf. Their rattling noise thrust itself into my head. A squad of Chinamen there puffed incessantly the menacing smell of cigars.

Were I the mayor of San Francisco—how romantic “the Mayor, Miss Morning Glory” sounds!—I would not pause a moment before erecting free bath-houses around the wharf.

I never dreamed that human beings could cast such an insulting smell.

The smell of honourable wagon drivers is the smell of a M-O-N-K-E-Y.

Their wild faces also prove their likeness to it.

They must have furnished all the evidence to Mr. Darwin. “The better part lies some distance from here,” said my uncle.

I exclaimed how inhospitable the Americans were to receive visitors from the back door of the city.

We are not empty-stomached tramps rapping the kitchen door for a crust of bread.

We refused hotel carriage.

We walked from the Oriental wharf for the sake of the street sight-seeing.

Tamageta wa! A house was whirling along the street. Look at the horseless car! How could it be possible to pull it with a rope under ground!

Everything reveals a huge scale of measurement.

The continental spectacle is different from that of our islands.

We 40,000,000 Japs must raise our heads from wee bits of land. There’s no room to stretch elbows. We have to stay like dwarf trees.

I shouldn’t be surprised if the Americans exclaim in Japan, “What a petty show!”

Such a riotous rush! What a deafening uproar!

The lazy halt of a moment on the street must have been regarded, I fancied, as a violation of the law.

I wondered whether one dozen were not slain each hour on Market Street by the cars.

Cars! Cars! And cars!

It was no use to look beautiful in such a cyclone city. Not even one gentleman moved his admiring eyes to my face.

How sad!

I thought it must be some festival.

“No, the usual Saturday throng!” my uncle said.

Then I asked myself whether Tokio streets were only like a midnight of this city.

My beloved minister kept his mouth open—what heavy lips he had!—amazed at the high edifices.

“O ho, that’s astonishing!” he cried, throwing his sottish eyes on the clock of the Chronicle building.

“Boys are commenting on you,” I whispered.

I beseeched him not to act so droll.

He tossed out in his careless fashion his everlasting heroic laughter, “Ha, ha, ha——”

A hawkish lad—I have not seen one sleepy fellow yet—drew near the minister shortly after we left the wharf, and begged to carry his bag.

He was only too glad to be assisted. The brown diplomatist thought it a loving deed toward a foreigner.

He bowed after some blocks, thanking the boy with a hearty “arigato.”

“Sir, you have to pay me two bits!”

His hand went to his pocket, when my uncle tapped his stooping back, speaking: “This is the country of eternal ‘pay, pay, pay,’ old man!”

“What does a genuine American beggar look like?” was my old question.

The Meriken beggar my friend saw at Yokohama park was dressed up in a swallow-tail coat. Emerson’s essays were in his hand. He was such a genteel Mr. Beggar, she said.

I often heard that everybody is a millionaire in America. I thought it likely that I should see a swell Mr. Beggar among the Americans.

How many a time had I planned to make a special trip to Yokohama for acquaintance with the honourable Emerson scholar!

Alas, it was merely a fancy!

I have seen Mr. Beggar on the street.

He didn’t appear in the formal dignity of a dress coat.

Where was his Emerson?

He was not unlike his Oriental brothers, after all.

He stood, because he wasn’t used to kneeling like the Japs.

The only difference was that he carried pencils instead of a musical instrument.

He is a merchant,—this is a business country,—while the Japanese Mr. Beggar is an artist, I suppose.

My little gold watch pointed eleven.

I have been writing for some hours about my first impression of the city from the wharf, and my journey from there to this Palace Hotel.

The number of my room is 489.

I fear I may not return if I once go out. It’s so hard to remember the number.

The large mirror reflected me as being so very small in the big room.

Such a great room with high ceiling!

I don’t feel at home at all.

Not a petal of flower. No inviting picture on the wall!

I was tired of hearing the artificial greeting, “Irasshai mashi,” or “Honourable welcome,” of the eternally bowing Japanese hotel attendants.

But the too simple treatment of ’Merican hotel is hardly to my taste.

Not even one girl to wait on me here!

No “honourable tea and cake.”

22nd—I need repose. The last few weeks have stirred me dreadfully. I will slumber just comfortably day after day, I decided.

But the same feeling as on the ocean returned.

My American bed acted like water, waving at even my slightest motion.

I fancied I was exercising even in sleep.

It is too soft.

Nothing can put me at complete ease like my hereditary lying on the floor.

I was restless all the night long.

I got up, since the bed was no joy.

Oh, the blue sky!

I thought I should never again see a sapphire sky while I am here. I was wrong.

This is church day.

The bells of the street-cars sounded musical.

The sky appeared in best Sunday dress.

I felt happy thinking that I should see the stars from my hotel window to-night.

I made many useless trips up and down the elevator for fun.

What a tickling dizziness I tasted!

I close my eyes when it goes.

It’s an awfully new thing, I reckon.

Something on the same plan, I imagine, as a “seriage” of the Japanese stage for a footless ghost rising to vanish.

It is astonishing to notice what a condescending manner the white gentlemen display toward ladies.

They take off their hats in the elevator—some showing such a great bald head, like a funny O Binzuru, that is as common as spectacled children—if any woman is present. They stand humbly as Japs to the august “Son of Heaven.” They crawl out like lambs after the woman steps away.

It puzzles me to solve how women can be deserving of such honour.

What a goody-goody act!

But I wonder how they behave themselves before God!

23rd—It is delightful to sit opposite the whitest of linen and—to portray on it the face of an imaginary Mr. Sweetheart while eating.

Whiteness is appetising.

And the boldly-marked creases of the linen are so dear. Without them the linen is not half so inviting.

I was taught the beauty of single line in drawing class some years ago.

But now for the first time I fully comprehended it from the Meriken tablecloth.

I wished I could ever stay gazing at it.

If I start my housekeeping in this country—do I ever dream of it?—I shall not hesitate to invest all my money in linen.

I laughed when I fancied that I sat with my husband—where’s he in the world?—spreading a skilfully ironed linen cloth on the Spring grasses (what a gratifying white and green!), and I upset a teapot over the linen, while he ran after water;—then I picked all the buttercups and covered the dark red stain.

The minister makes a ridiculous show of himself in the dining-room.

His laughter draws the attention of every lady.

This morning he exclaimed: “Americans have no courtesy for strangers, except meaning money.”

And he finished his speech with his boisterous “Ha, ha, ha!”

A pale impatient lady, like a trembling winter leaf, sitting at the table next to us, shrugged her shoulders and muttered, “Oh, my!”

I hoped I could invent any scheme to make him hasten to his post—Kara or Tenjiku, whatever place it be.

He is good-natured like a rubber stamp.

But I am sorry to say that he does not fit Amerikey.

I was relieved when he announced that his departure would occur to-morrow.

My dignity was saved.

I cut a square piece of paper. I pencilled on it as follows:

I put it on the large palm of the minister. I warned him that he should never forget to pin it on his breast.

“Mean little thing you are!” he said.

And his great happy “Ha, ha, ha!” followed as usual.

Bye-bye!

The negroes are horrid. I scanned them on the first chance of my life.

What is the standard of beauty of their tribe, I am eager to be informed!

I searched for “coon” in my dictionary. The explanation was unsatisfactory.

The ever-so-kind Americans don’t consider them, I am certain, as “animals allied to the bear.”

Tell me what it means.

24th—Spittoon!

The American spittoon is famous, Uncle says.

From every corner in this nine-story hotel—think of its eight hundred and fifty-one rooms!—you are met by the greeting of the spittoon.

How many thousand are there?

It must be a tremendous task to keep them clean as they are.

I wonder why the proprietor doesn’t give the city the benefit of some of them.

San Francisco ought to place spittoons along the sidewalk.

The ladies wear such a long gaudy skirt.

And it is quite a fashion of modern gents, it appears, to spit on the pavements.

This Palace Hotel is a palace.

You drop into the toilet room, for instance.

You cannot help exclaiming: “Iya, haya, Japan is three centuries behind!”

Everything presents to you a silent lecture of scientific modernism.

Whenever I am bothered too much by my uncle I lock myself up in the toilet room. There I feel the whole world is mine.

I can take off my shoes. I can play acrobat if I prefer.

Nobody can spy me.

It is the place where you can pray or cry all you desire without one interruption.

My room is great, equipped with every new invention. Numbers of electric globes dazzle with kingly light above my head.

If I enter my room at dusk, I push a button of electricity.

What a satisfaction I earn seeing every light appear to my honourable service!

I look upon my finger wondering how such an Oriental little thing can make itself potent like the mighty thumb of Mr. Edison.

25th—What a novel sensation I felt in writing “San Francisco, U.S.A.,” at the head of my tablet!

(What agitation I shall feel when I write my first “Mrs.” before my name! Woman must grow tired of being addressed “Miss,” sooner or later.)

I have often said that I hardly saw any necessity for corresponding when one lives on such a small island as Japan.

I could see my friends in a day or two, at whatever place I was.

I have now the ocean between me and my home.

Letter writing is worth while.

I did not know it was such a sweet piece of work.

I should declare it to be as legitimate and inexpensive a game as ever woman could indulge in.

I was stepping along the courtyard of this hotel.

I have seen a gentleman kissing a woman.

I felt my face catching fire.

Is it not a shame in a public place?

I returned to my apartment. The mirror showed my cheeks still blushing.

The Japanese consul and his Meriken wife—she is some inches higher than her darling—paid us a call.

I said to myself that they did not match well. It was like a hired haori with a different coat of arms.

The Consul looked proud, as if he carried a crocodile.

Mrs. Consul invited us for luncheon next Sunday.

“Quite a family party—O ho, ho!”

Her voice was unceremonious.

I noticed that one of her hairpins was about to drop. I thought that Meriken woman was as careless as I.

How many hairpins do you suppose I lost yesterday?

Four! Isn’t that awful?

My uncle innocently stated to her I was a great belle of Tokio.

I secretly pinched his arm through his coat-sleeve. My little signal did not influence him at all. He kept on his hyperbolical advertisement of me.

She promised a beautiful girl to meet me on Sunday.

I fancied how she looked.

I thought my performance of the first interview with Meriken woman was excellent. But my rehearsal at home was useless.

26th—I lost my little charm.

It worried me awfully.

It was given me by my old-fashioned mother. She got it after a holy journey of one month to the shrine of Tenno Sama.

I should be safe, Mother said, from water, fire and highwayman (what else, God only knows) as long as I should carry it.

I sought after it everywhere. I begged my uncle to let me examine his trunk.

“Cast off an ancient superstition!” Uncle scorned.

I sat languidly on the large armchair which almost swallowed my small body.

I imagined many a punishment already inflicted on me.

The tick-tack of my watch from my waist encouraged my nervousness.

There is nothing more irritating than a tick-tack.

I locked up my watch in the drawer of the dresser.

I still felt its tick-tack pursuing my ears.

Then I put it under the pillow.

27th—How I wished I could exchange a ten-dollar gold-piece for a tassel of curly hair!

American woman is nothing without it.

Its infirm gesticulation is a temptation.

In Japan I regarded it as bad luck to own waving hair.

But my tastes cannot remain unaltered in Amerikey.

I don’t mind being covered with even red hair.

Red hair is vivacity, fit for Summer’s shiny air.

I remember that I trembled at sight of the red hair of an American woman at Tokio. Japanese regard it as the hair of the red demon in Jigoku.

I sat before the looking-glass, with a pair of curling-tongs.

I tried to manage them with surprising patience. I assure you God doesn’t vouchsafe me much patience.

Such disobedient tools!

They didn’t work at all. I threw them on the floor in indignation.

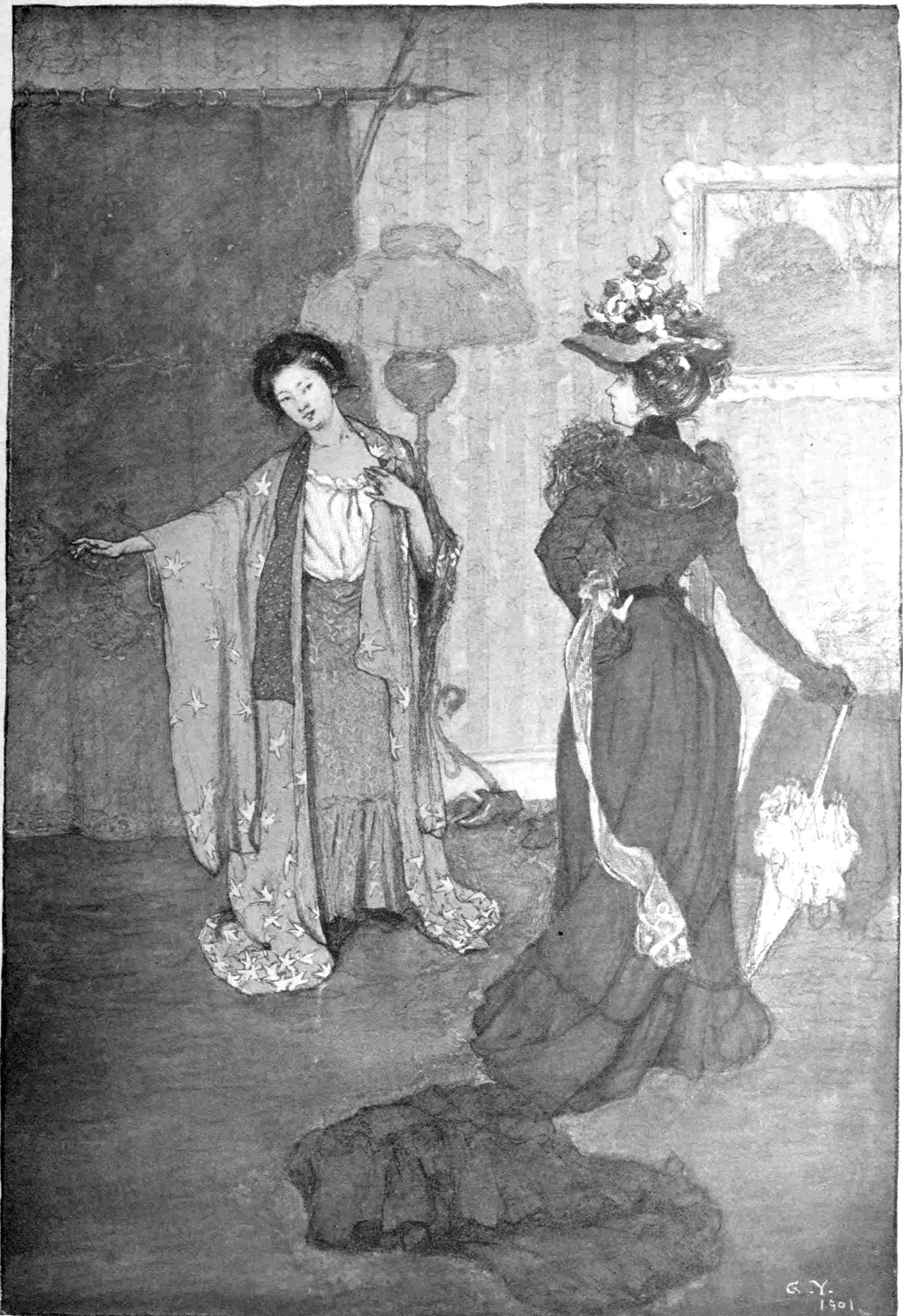

Drawn by Genjiro Yeto

“Such Disobedient Tools!”

My wrists pained.

I sat on the floor, stretching out my legs. My shoe-strings were loosed, but my hand did not hasten to them.

I was exhausted with making my hair curl.

I sent my uncle to fetch a hair-dresser.

28th—How old is she?

I could never suggest the age of a Meriken woman.

That Miss Ada was a beauty.

It’s becoming clearer to me now why California puts so much pride in her own girls.

Ada was a San Franciscan whom Mrs. Consul presented to me.

What was her family name?

Never mind! It is an extra to remember it for girls. We don’t use it.

How envious I was of her long eyelashes lacing around the large eyes of brown hue!

Brown was my preference for the velvet hanao of my wooden clogs.

Long eyelashes are a grace, like the long skirt.

I know that she is a clever young thing.

She was learned in the art of raising and dropping her curtain of eyelashes. That is the art of being enchanting. I had said that nothing could beat the beauty of my black eyes. But I see there are other pretty eyes in this world.

Everything doesn’t grow in Japan. Noses particularly.

My sweet Ada’s nose was an inspiration, like the snow-capped peak of O Fuji San. It rose calmly—how symmetrically!—from between her eyebrows.

I had thought that ’Merican nose was rugged, big of bone.

I see an exception in Ada.

She must be the pattern of Meriken beauty.

I felt that I was so very homely.

I stole a sly glance into the looking-glass, and convinced myself that I was a beauty also, but Oriental.

We had different attractions.

She may be Spring white sunshine, while I am yellow Autumn moonbeams. One is animation, and the other sweetness.

I smiled.

She smiled back promptly.

We promised love in our little smile.

She placed her hand on my shoulder. How her diamond ring flashed! She praised the satin skin of my face.

She was very white, with a few sprinkles of freckles. Their scattering added briskness to the face in her case. (But doesn’t San Francisco produce too many freckles in woman?) The texture of Ada’s skin wasn’t fine. Her face was like a ripe peach with powdery hair.

Is it true that dark skin is gaining popularity in American society?

The Japanese type of beauty is coming to the front then, I am happy.

I repaid her compliment, praising her elegant set of teeth.

Ada is the free-born girl of modern Amerikey.

She need never fear to open her mouth wide.

She must have been using special tooth-powder three times a day.

“We are great friends already, aren’t we?” I said.

And I extended my finger-tips behind her, and pulled some wisps of her chestnut hair.

“Please, don’t!” she said, and raised her sweetly accusing eyes. Then our friendship was confirmed.

Girls don’t take much time to exchange their faith.

I was uneasy at first, thinking that Ada might settle herself in a tête-à-tête with me, in the chit-chat of poetry. I tried to recollect how the first line of the “Psalm of Life” went, for Longfellow would of course be the first one to encounter.

Alas, I had forgotten it all.

I was glad that her query did not roam from the remote corner of poesy.

“Do you play golf?” she asked.

She thinks the same things are going on in Japan.

Ada! Poor Ada!

The honourable consul and my uncle looked stupid at the lunch table.

I thought they were afraid of being given some difficult question by the Meriken ladies.

Mrs. Consul and Ada ate like hungry pigs. (I beg their pardon!)

“You eat like a pussy!” is no adequate compliment to pay to a Meriken woman.

I found out that their English was neither Macaulay’s nor Irving’s.

29th—I ate a tongue and some ox-tail soup.

Think of a suspicious spumy tongue and that dirty bamboo tail!

Isn’t it shocking to even incline to taste them?

My mother would not permit me to step into the holy ground of any shrine in Japan. She would declare me perfectly defiled by such food.

I shall turn into a beast in the jungle by and by, I should say.

My uncle committed a greater indecency. He ate a tripe.

It was cooked in the “western sea egg-plant,” to taste of which brings on the small-pox, as I have been told.

He said that he took a delight in pig’s feet.

Shame on the Nippon gentleman!

Harai tamae! Kiyome tamae!

30th—“Chui, chui, chui!”

A little sparrow was twittering at my hotel window.

I could not believe that the sparrow of large America could be as small as the Nippon-born.

Horses are large here. Woman’s mouth is large, something like that of an alligator. Policeman is too large.

I fancied that little birdie might be one strayed from the bamboo bush of my family’s monastery.

“Sweet vagabond, did you cross the ocean for Meriken Kenbutsu?” I said.

“Chui, chui! Chui, chui, chui!” he chirped.

Is “chui, chui” English, I wonder?

I pushed the window up to receive him.

Oya, ma, he has gone!

I felt so sorry.

I was yearning after my beloved home.

This is the great Chrysanthemum season at home. I missed the show at Dangozaka.

How gracefully the time used to pass in Dai Nippon, while I sat looking at the flowers on a tokonoma.

Every place is a strange gray waste to me without the intimate faces of flowers.

Flowers have no price in Japan, just as a poet is nothing, for everybody there is poet. But they have a big value in this city—although I am not positive that an American poet creates wealth.

I purchased a select bouquet of violets.

I passed by several young gentlemen. Were their eyes set on my flowers or my hands?

I don’t wear gloves. I don’t wish my hands to be touched harshly by them. Truly I am vain of showing my small hands.

I love the violet, because it was the favorite of dear John—Keats, of course.

It may not be a flower. It is decidedly a perfume, anyhow.

31st—I have heard a sad piece of news from Mrs. Consul about Mr. Longfellow.

She says that he has ceased to be an idol of American ladies.

He has retired to a comfortable fireside to take care of school children.

Poor old poet!

Nov. 1st—American chair is too high.

Are my legs too short?

It was uncomfortable to sit erect on a chair all the time as if one were being presented before the judge.

And those corsets and shoes!

They seized me mercilessly.

I said that I would spend a few hours in Japan style, reclining on the floor like an eloped angel.

I brought out a crape kimono and my girdle with the phœnix embroidery, after having locked the entrance of my room.

“Kotsu, kotsu, kotsu!”

Somebody was fisting on my door.

Oya, she was Ada, my “Rose of Frisco” or “Butterfly of Van Ness.”

(She was quartered in Van Ness Avenue, the most elegant street of a whole bunch.)

She was sprightly as a runaway princess. She blew her sunlight and fragrance into my face.

I was grateful that I chanced to be acquainted with such a delightful Meriken lady.

“O ho, Japanese kimono! If I might only try it on!” she said.

I told her she could.

“How lovely!” she ejaculated.

We promised to spend a gala day together.

Drawn by Genjiro Yeto

“O ho, Japanese kimono!”

“We will rehearse,” I said, “a one-act Japanese play entitled ‘Two Cherry Blossom Musumes.’”

I assisted her to dress up. She was utterly ignorant of Oriental attire.

What a superb development she had in body! Her chest was abundant, her shoulders gracefully commanding. Her rather large rump, however, did not show to advantage in waving dress. Japs prefer a small one.

My physical state is in poverty.

I was wrong to believe that the beauty of woman is in her face.

It is so, of course, in Japan. The brown woman eternally sits. The face is her complete exhibition.

The beauty of Meriken woman is in her shape.

I pray that my body may grow.

The Japanese theatre never begins without three rappings of time-honoured wooden blocks.

I knocked on the pitcher.

Miss Ada appeared from the dressing room, fluttering an open fan.

How ridiculously she stepped!

It was the way Miss What’s-her-name acted in “The Geisha,” she said.

She was much taller than little me. The kimono scarcely reached to her shoes. I have never seen such an absurd show in my life.

I was tittering.

The charming Ada fanned and giggled incessantly in supposed-to-be Japanese chic.

“What have I to say, Morning Glory?” she said, looking up.

“I don’t know, dear girl!” I jerked.

Then we both laughed.

Ada caught my neck by her arm. She squandered her kisses on me.

(It was my first taste of the kiss.)

We two young ladies in wanton garments rolled down happily on the floor.

2nd—If I could be a gentleman for just one day!

I would rest myself on the hospitable chair of a barber shop—barber shop, drug store and candy store are three beauties on the street—like a prince of leisure, and dream something great, while the man is busy with a razor.

I am envious of the gentleman who may bathe in such a purple hour.

I never rest.

American ladies neither!

Each one of them looks worried as if she expected the door-bell any moment.

I suppose it is the penalty of being a woman.

3rd—My little heart was flooded with patriotism.

It is our Mikado’s birthday.

I sang “The Age of Our Sovereign.” I shouted “Ten thousand years! Banzai! Ban banzai!”

My uncle and I hurried to the Japanese Consulate to celebrate this grand day.

4th—The gentlemen of San Francisco are gallant.

They never permit the ladies—even a black servant is in the honourable list of “ladies”—to stand in the car.

If Oriental gentlemen could demean themselves like that for just one day!

I should not mind a bit if one proposed to me even.

I love a handsome face.

They part their hair in the middle. They have inherited no bad habit of biting their finger-nails. I suppose they offer a grace before each meal. Their smile isn’t sardonic, and their laughter is open.

I have no dispute with their mustaches and their blue eyes. But I am far from being an admirer of their red faces.

Japs are pygmies. I fear that the Americans are too tall. My future husband is not allowed to be over five feet five inches. His nose should be of the cast of Robert Stevenson’s.

Each one of them carries a high look. He may be the President at the next election, he seems to say. How mean that only one head is in demand!

A directory and a dictionary are kind. The ’Merican husband is like them, I imagine.

I have no gentleman friend yet.

To pace alone on the street is a melancholy discarded sight.

What do you do if your shoe-string comes untied?

I have seen a gentleman fingering the shoestrings of a lady. How glad he was to serve again, when she said, “That’s too tight!”

Shall my uncle fill such a part?

Poor uncle!

Old company, however, isn’t style.

He is forty-five.

Why can I not choose one to hire from among the “bully” young men loitering around a cigar-stand?

5th—My uncle was going out in a black frock-coat and tea-coloured trousers. I insisted that his coat and trousers didn’t match.

How can a man be so ridiculous?

I declared that it was as poor taste as for a darkey to wear a red ribbon in her smoky hair.

Uncle surrendered.

He said, “Hei, hei, hei!”

Goo’ boy!

He dismissed the great tea-colour.

6th—We had a shower.

The city dipped in a bath.

The pedestrians threw their vaguely delicate shadows on the pavements. The ladies voluntarily permitted the gentlemen to review their legs. If I were in command, I would not permit the ladies to raise an umbrella under the “para para” of a shower. Their hastening figures are so fascinating.

The shower stopped. The pavements were glossed like a looking-glass. The windows facing the sun scattered their sparkling laughter.

How beautiful!

I am perfectly delighted by this city.

One thing that disappoints me, however, is that Frisco is eternally snowless,

Without snow the year is incomplete, like a departure without sayonara.

Dear snow! O Yuki San!

Many Winters ago I modelled a doll of snow, which was supposed to be a gentleman.

How proud I used to be when I stamped the first mark with my high ashida on the white ground before anyone else!

I wonder how Santa Claus will array himself to call on this town.

His fur coat is not appropriate at all.

7th—Why didn’t I come to Amerikey earlier—in the Summer season?

I was staring sadly at my purple parasol against the wall by my dresser.

I have no chance to show it.

I have often been told that I look so beautiful under it.

8th—My darling O Ada came in a carriage. Her two-horsed carriage was like that of our Japanese premier.

She is the daughter of a banker.

The sun shone in yellow.

Ada’s complexion added a brilliancy. I was shocked, fearing that I looked awfully brown.

Ada said that I was “perfectly lovely.” Can I trust a woman’s eulogy?

I myself often use flattery.

A jewel and face-powder were not the only things, I said, essential to woman.

We drove to the Golden Gate Park and then to the Cliff House.

What a triumphant sound the hoofs of the bay horses struck! I fancied the horses were a poet, they were rhyming.

I don’t like the automobile.

Ada was sweet as could be.

“Tell me your honourable love story!” she chattered.

I did only blush.

I hadn’t the courage to burst my secrecy.

I loved once truly.

It was an innocent love as from a fairy book.

If true love could be realised!

In the park I noticed a lady who scissored the “don’t touch” flowers and stepped away with a saintly air. The comical fancy came to me that she was the mother of a policeman guarding against intruders.

We found ourselves in the Japanese tea garden.

A tiny musume in wooden clogs brought us an honourable tea and o’senbe.

The grounds were an imitation of Japanese landscape gardening.

Homesickness ran through my fibre.

The decorative bridge, a stork by the brook, and the dwarf plants hinted to me of my home garden.

A sudden vibration of shamisen was flung from the Japanese cottage close by.

“Tenu, tenu! Tenu, tsunn shann!”

Who was the player?

When I sat myself by the ocean on the beach I found some packages of peanuts right before me.

The beautiful Ada began to snap them.

She hummed a jaunty ditty. Her head inclined pathetically against my shoulder. My hair, stirred by the sea zephyrs, patted her cheek.

She said the song was “My Gal’s a High-Born Lady.”

Who was its author? Emerson did not write it surely.

When I returned to the hotel, I undertook to place on the wall the weather-torn fragment of cotton which I had picked up at the park.

These words were printed on it: