This philosopher continued saying: “People may envy my writings or refuse them their reward, but they are unable to diminish their reputation; and if they did, what should hinder me from scorning their opinions?”

(68.) It is a good thing to be a philosopher, but it does not much benefit a man to be thought one. It will be considered an insult to call any one a philosopher till the general voice of mankind has declared it otherwise, given its true meaning to this beautiful word, and granted it all the esteem it deserves.

(69.) There is a philosophy which raises us above ambition and fortune, and not only makes us the equals of the rich, the great, and the powerful, but places us above them; makes us contemn office and those who appoint to it; exempts us from wishing, asking, praying, soliciting, and begging for anything, and even restrains our emotion and our excessive exultation when successful. There is another philosophy which inclines and subjects us to all these things for the sake of our relatives and friends; and this is the better of the two.

(70.) It will shorten and rid us of a thousand tedious discussions to take it for granted that some persons are not capable of talking correctly, and to condemn all they have said, do say, or will say.

(71.) We only approve in others those qualities in which we imagine they resemble us; thus, to esteem any one seems to make him an equal of ourselves.

(72.) The same faults which are dull and unbearable in others are in their right place when we have them; they do not weigh us down, and are hardly felt. One man, speaking of another, draws a terrible likeness of him, and does not in the least imagine that at the same time he is painting himself.

If we could see the faults in other people, and could be brought to acknowledge that we possess the same faults, we would more readily amend them; it is when we are at a right distance from them, and when they appear what they really are, that we dislike them as much as they deserve.

(73.) A wise manʼs behaviour turns on two pivots, the past and the future. If he has a good memory and a keen foresight, he runs no danger of censuring in others what perhaps he has done himself, or of condemning an action which, in a parallel case, and in like circumstances, he sees it will be impossible for him to avoid.

(74.) Neither a soldier, a politician, nor a skilful gambler644 create luck, but they prepare it, allure it, and seem almost to fix it. They not only know what a fool and a coward ignore, I mean, to make use of luck when it does come, but by their precautions and measures they know how to take advantage of a lucky chance, or of several chances together. If a certain deal or throw succeeds, they gain; if another happens, they also win; and often profit by one and the same in various ways. These sharp men may be commended both for their good fortune and prudent conduct, and they should be rewarded for their luck as other men are for their virtue.

(75.) I place nobody above a great politician but a man who does not care to become one, and who is more and more convinced that it is not worth troubling himself about what is going on in the world.

(76.) In the best of counsels there is something to displease us; they are not our own thoughts; and, therefore, presumption and caprice at first cause them to be rejected, whilst we only follow them through necessity or after having reflected.

(77.) This favourite has been wonderfully fortunate during his whole lifetime; he enjoyed an uninterrupted good fortune, was never in disgrace, occupied the highest posts, was in the kingʼs confidence, had vast treasures, perfect health, and died quietly. But what an extraordinary account he will have to render of a life spent as a favourite, of advice given, of advice which was not tendered or not listened to, of good deeds omitted, and, on the contrary, of evil ones committed, either by himself or his instruments; in a word, of all his prosperity.645

(78.) When we are dead we are praised by those who survive us, though we frequently have no other merit than that of being no longer alive; the same commendations serve then for Cato and for Piso.646

“There is a report that Piso is dead; it is a great loss; he was an honest man, who deserved to live longer; he was intelligent and agreeable, resolute and courageous, to be depended upon, generous and faithful;” add: “provided he be really dead.”

(79.) The way in which we exclaim about certain persons being distinguished for their good faith, disinterestedness, and honesty is not so much to their praise as to the disrepute of all mankind.

(80.) A certain person relieves the necessitous, but neglects his own family and leaves his son a beggar; another builds a new house though he has not paid for the lead of the one finished ten years before; a third makes presents and is very liberal, but ruins his creditors. I would fain know whether pity, liberality, and magnificence can be the virtues of a man without sense, or whether eccentricity and vanity are not rather the causes of this want of sense.647

(81.) If we wish to be essentially just to others, we should be quick and not dilatory; to let people wait is to commit an injustice.

Those persons do well, or do their duty, who do what they ought. A man who allows the world to speak always of him in the future tense, and to say he will do well, behaves really very badly.

(82.) People say of a great man who has two meals a day, and spends the rest of his time in digesting what he has eaten, that he starves; all that they mean to express by this is that he is not rich, or that his affairs are not very prosperous; the remark about starving might be better applied to his creditors.

(83.) The culture, good manners, and politeness of persons of either sex, advanced in years, give me a good opinion of what we call “former times.”648

(84.) Parents are over-confident in expecting too much from the good education of their children, and commit a grievous error if they expect nothing from it and neglect it.

(85.) Were it true, as several persons affirm, that education does not alter the heart and constitution of man, and that in reality the changes it produces transform nothing and are merely superficial, yet I would still maintain that it is beneficial to him.

(86.) He who speaks little has this advantage, that he is presumed to have some intelligence, and if he really is not deficient in it, it is presumed to be first-rate.

(87.) To think only of ourselves and of the present time is a source of error in politics.

(88.) Next to being convicted of a crime, it is often the greatest misfortune for a man his being accused of having committed one, and being obliged to clear himself from the charge. He may be acquitted in a court of justice and yet be found guilty by the voice of the people.649

(89.) One man faithfully observes certain religious duties and discharges them carefully, yet he is neither commended nor censured, he is not so much as thought of; another, after ten yearsʼ utter neglect of such duties, attends again to them and is commended and extolled. Every person has a right to his own opinion; I, for my part, blame the second man for having so long neglected those duties, and think his reformation fortunate for himself.

(90.) A flatterer has not a sufficiently good opinion of himself or others.

(91.) Some men are forgotten in the distribution of favours, and we ask what can be the reason of this; if they had not been forgotten we should have raised the question why they had received them. Whence proceeds this dissimilitude? Is it from the character of these persons, or the instability of our opinions, or rather from both?

(92.) We often hear the question asked, “Who shall be chancellor, primate,650 pope?” People go even farther, and, according to their own wishes or caprice, often promote persons more aged and infirm than those who at present fill certain posts; and as there is no reason why any post should kill its occupant, but, on the contrary, often makes him young again, and reinvigorates his body and soul, it is not unusual for an official personage to outlive his appointed successor.651

(93.) Disgrace extinguishes hatred and jealousy. As soon as a person is no longer a favourite, and when we do not envy him any more, we admit that his actions are good, and we can pardon in him any merit and a good many virtues; he might even be a hero, and not vex us.

Nothing seems right that a man does who has fallen into disgrace; his virtues and merit are slighted, misinterpreted, or called vices. If he is courageous, dreads neither fire nor sword, and faces the enemy with as much bravery as Bayard and Montrevel,652 he is called a “braggadocio,” and they make fun of him, for there is nothing of the true hero about him.

I contradict myself; I own it; do not blame me, but blame those men whose judgments I merely give, and who are the very same persons, though they differ so much and are so variable in their opinions.

(94.) We need not wait twenty years to see a general alter his opinion on the most serious things as well as on those which appear most certain and true. I shall not venture to maintain that fire in its own nature, and independent of our sensations, is void of heat,653 that is to say, nothing like what we feel in ourselves on approaching it, lest some time or other it may become as hot as ever it was thought; nor shall I advance that one straight line falling on another makes two right angles, or two angles equal to two right angles, for fear something more or less be discovered, and my proposition be laughed at; nor, to mention something else, shall I say, with the whole of France, that Vauban is infallible, and that this is an undoubted fact,654 for who will guarantee me but that in a short time it may be hinted that even in sieges, in which lies his peculiar pre-eminence, and of which he is considered the best judge, he does not make some blunders, and is as liable to mistakes as Antiphilus is?655

(95.) If you believe people who are exasperated against one another, and swayed by passion, a scholar is a mere sciolist,656 a magistrate a boor or a pettifogger,657 a financier an extortioner, and a nobleman an upstart; but it is strange these scurrilous names, invented by anger and hatred, should become so familiar to us, and that contempt, though cold and inert, should dare to employ them.

(96.) You agitate yourself, and give yourself a good deal of trouble, especially when the enemy begins to fly, and the victory is no longer doubtful, or when a town has capitulated; in a fight or during a siege you like to be seen everywhere in order to be nowhere; to forestall the orders of the general for fear of obeying them, and to seek opportunities rather than to wait for them or receive them. Is your courage a mere pretence?

(97.) Order your soldiers to keep some post where they may be killed, and where nevertheless they are not killed, and they prove they love both honour and life.

(98.) Can we imagine that men who are so fond of life should love anything better, and that glory, which they prefer to life, is often no more than an opinion of themselves, entertained by a thousand people whom either they do not know or do not esteem?658

(99.) Some persons who are neither soldiers nor courtiers make a campaign and follow the court; they do not assist in besieging a town, but are merely spectators,659 and are soon cured of their curiosity about a fortified place, however wonderful; about trenches; the effects of shells and cannon, about surprises, and the order and success of an attack of which they catch a mere glimpse. The place holds out, bad weather comes on, fatigues increase, the mud has to be waded through, and the seasons have to be encountered as well as the enemy; the lines may be forced, and we may find ourselves between the town and an army, and reduced to dire extremities. The besiegers lose heart, begin to murmur, and ask if the raising of the siege will be of such great consequence, and if the safety of the State depends on one citadel. They further add “that the heavens themselves declare against them; and that it is best to submit, and put off the siege until another season.” They no longer understand the firmness, and, if they may say so, the obstinacy of the general, who is not to be overcome by obstacles, but is stimulated by the difficulty of his undertaking, and watches by night and exposes his life by day to accomplish his design. But as soon as the enemy has capitulated, the very men who lost heart boast of the importance of the conquest, foretell the consequences it will have, exaggerate the necessity there was in undertaking it, as well as the danger and shame there would have been in raising it, and prove that the army opposed to the enemy was invincible.660

They return with the court, and as they pass through the towns and villages, are proud to be looked upon by the inhabitants, who are all at their windows, as the very men who took the place; thus they triumph all along the road and fancy themselves very courageous. When they are home again they deafen you with flanks, redans, ravelins, counter breastworks,661 curtains, and covert-ways; give you an account of the spots where curiosity led them, and where it was pretty dangerous, and of the risks they ran on returning of being killed or made prisoners; but they do not say one word about the mortal terror they were in.

(100.) It is no great disadvantage for a speaker to stop short in the middle of a sermon or a speech; it does not deprive him of his intelligence, good sense, imagination, morals, and learning; it robs him of nothing; but it is very surprising that, though it is considered more or less disgraceful and ridiculous, some men will expose themselves to so great a risk by tedious and often unprofitable discourses.

(101.) Those who make the worst use of their time are the first to complain of its brevity; as they waste it in dressing themselves, in eating and sleeping, in foolish conversations, in making up their minds what to do, and, generally, in doing nothing at all, they want some more for their business or for their pleasures, whilst those who make the best use of it have some to spare.

There is no minister of State so busy but he knows he loses two hours every day, which amounts to a great deal in a long life; and if this waste is still greater among other conditions of men, what a large loss is there of what is most precious in this world, and of which every one complains he has not enough.

(102.) There exist some of Godʼs creatures called men, who have a spiritual soul, and who spend their whole lives in the sawing of marble, and devote all their attention to it; this is a very humble business and of not much consequence; there are other people who are astonished at this, yet who are of no use whatever, and spend their days in doing nothing, which is inferior to sawing marble.

(103.) Most men are so oblivious of their souls, and act and live in such a manner, that to them it seems to be of no use whatever; we therefore deem it no small commendation of any man to say he thinks; this has become a common eulogy, and yet it places a man only above a dog or a horse.

(104.) “How do you amuse yourself? How do you pass your time?” fools and clever people ask you. If I answer, in opening my eyes, in seeing, hearing, and understanding, in enjoying health, rest, and freedom, that is nothing; the solid, the great, and the only advantages of life are of no account. “I gamble, I intrigue,” are the answers they expect.

Is it good for a man to have too great and extensive a freedom, which only induces him to wish for something else, which would be to have less liberty?

Liberty is not indolence; it is a free use of time; it is to choose our labour and our relaxation; in one word, to be free is not to do nothing, but to be the sole judge of what we wish to do and to leave undone; in this sense liberty is a great boon.

(105.) Cæsar was not too old to think of conquering the entire world; his sole happiness was to lead a noble life and to leave behind him a great name; being naturally proud and ambitious, and enjoying robust health, he could not better employ his time than in subjugating all nations. Alexander was very young for so serious a design; it is surprising that women or wine did not sooner ruin the undertaking of a man of such tender years.662

(106.) A young prince, of an august race,663 the love and hope of his people, granted by Heaven to prolong the felicity of this earth, greater than his ancestors, the son of a hero who is his exemplar, has by his divine qualities and anticipated virtues already convinced the universe that the sons of heroes are nearer being so than other men.664

(107.) If the world is only to last a hundred million years, it is still in all its freshness, and has but just begun; we ourselves are so near the first men and the patriarchs, that remote ages will not fail to reckon us among them. But if we may judge of what is to come by what is past, what new things will spring up in arts, sciences, in nature, and, I venture to say, even in history, which are as yet unknown to us! What discoveries will be made! What various revolutions will happen in states and empires! What ignorance must be ours, and how slight is an experience of not above six or seven thousand years!

(108.) No way is too tedious for him who travels slowly and without being in a hurry; no advantages are too remote for those who have patience.

(109.) To court nobody, and not to expect to be courted by any one, is a happy condition, a golden age, and the most natural state of man.665

(110.) Those who follow courts or live in towns only care for the world; but those who dwell in the country care for nature, for they alone live, or at least know that they live.

(111.) Why this coldness, and why do you complain of some expressions which escaped me about some of our young courtiers? You are not vicious, Thrasyllus? If you are, it is unknown to me; but you yourself tell me so; what I do know is that you are no longer young.

You are personally offended at what I said of some great men, but you should not cry out when other people are hurt. Are you haughty, wicked, a buffoon, a flatterer, or a hypocrite? I protest I was ignorant of it, and did not think of you; I was speaking of men of high rank.

(112.) Moderation and a certain prudent behaviour leave men unknown; in order to be known and admired they must have great virtues, or perhaps great vices.

(113.) Whether men are of a superior or of an inferior condition, as soon as they are successful, their fellow-men are prejudiced in their favour, delighted and in raptures; a crime which has not failed is almost as much commended as real virtue, and luck supplies the place of all qualities; it must be an atrocious action, a foul and nefarious attempt indeed, which success cannot justify.666

(114.) Men, led away by fair appearances and specious pretences, are easily induced to like and approve an ambitious scheme contrived by some great man; they speak feelingly of it; its boldness or novelty pleases them; it is already familiar to them, and they expect naught but its success. But should it happen to miscarry, they confidently, and without any regard for their former judgment, decide that the plan was rash and could never succeed.667

(115.) Certain designs are of such great splendour and of such enormous consequence, that people talk about them for a long time; that they lead nations to fear or to hope, according to their various interests, and that a man stakes his glory and his entire fortune on them. After appearing on the worldʼs stage with such pomp he cannot slink away in silence; whatever terrible dangers he foresees will be the consequences of his undertaking; he must commence it; the smallest evil he has to expect will be a failure.

(116.) You cannot make a great man of a wicked man; you may commend his plans and contrivances, admire his conduct, extol his skill in employing the surest and shortest means to obtain his end; but if his purpose be bad, prudence has no share in it, and where prudence is wanting no greatness can ever exist.

(117.) An enemy is dead who was at the head of a formidable army, and intended to cross the Rhine; he understood the art of war, and his experience might have been seconded by fortune. What bonfires were lit, and what rejoicings took place! But there are other men, naturally odious, who are disliked by every one; it is therefore not on account of their success, nor because people fear they might be successful, that the voice of the public is lifted up, and that the very childrenʼs hearts leap for joy as soon as it is rumoured abroad that the earth is at length rid of them.668

(118.) “O times! O morals!”669 exclaims Heraclitus.670

“O unfortunate age, rich in bad examples, when virtue

is persecuted and crime is predominant and triumphant!”

I will turn a Lycaon or an Ægistheus,671 for I can never

meet with a better opportunity nor a more favourable conjuncture;

if, at least, I desire to be prosperous and to

flourish. A certain personage672 says, “I will cross the

sea; I will dispossess my father of his patrimony; I will

drive him, his wife, and his heir from their territory and

kingdom;” and he not only says it but does it. What

he had reason to dread was the resentment of many

kings, insulted in the person of one monarch. But they

side with him; they almost have said to him: “Cross

the sea, rob your father; and let the entire world witness

how a king can be driven from his kingdom, as if he

were a petty lord turned out from his castle, or a farmer

from his farm; show them that there is no longer

any difference between private persons and ourselves.

We are tired of these distinctions; teach the world that

the nations whom God has placed underneath our feet

may abandon us, betray us, and give us up, and themselves

as well, into the hands of the stranger, and that they

have less to fear from us than we have to dread them

and their power.”673 What person can behold such a

sad scene without shedding tears or being deeply moved!

Every office has its privileges, and every official speaks,

pleads, and agitates to defend them; the royal dignity

alone enjoys no longer such privileges, and the kings

themselves have renounced them. Only one among

them, ever kind-hearted and magnanimous, opens his

arms to receive an unhappy family;674 all the others

league themselves against him as if to avenge the assistance

he lends to a cause which is theirs as well; spite

and jealousy have more weight with them than considerations

for their honour, religion, and rule, and even

than domestic and personal interests; they do not perceive

that, I will not say their election, but their very

succession, and even their hereditary rights are at stake.

Finally, in every one of them personal feelings prevail

over those of a sovereign. One prince was going to set

Europe free, and free himself as well from an ominous

enemy; he was just on the point of reaping the glory of

having destroyed a mighty empire when he abandoned

his plan, and joined in a war in which success is far from

certain.675 Those rulers who by virtue of their position

are arbitrators and mediators temporise; and when they

could already have interfered and done some good, they

only promise they will do so.676 “O shepherds,” continues

Heraclitus, “O ye rustics who dwell in hovels

and cottages; if the course of events does not affect

you, if your hearts are not pierced by the malice of

men, if man is no longer mentioned among you, but

foxes and lynxes are the only subjects of your conversation,

allow me to dwell with you, to appease my hunger

with your black bread, and to quench my thirst with the

water from your wells.”

(119.) Ye little men, only six feet high, or at most seven, who, as soon as you have reached eight feet, are to be seen for money in booths at the fairs, as giants and wonders; who, without blushing, give yourselves the titles of “highnesses” and “eminences,” which is the utmost that can be granted to those mountain-tops so near the sky that they see the clouds form underneath them; ye haughty, vain-glorious animals who despise all other creatures, and who cannot even be compared to an elephant or a whale, draw near, ye men, and answer Democritus. Do you not commonly speak of “hungry wolves, furious lions, and mischievous monkeys?” Pray, who are you? “Man is a rational creature” is continually dinned in my ears. Who gave you this appellation? Did the wolves, or the lions, or the monkeys do so, or did you take it yourselves? It is already very ridiculous that you should bestow on animals, your fellow-creatures, all the bad epithets, and take the best for yourselves; leave it to them to give names, and you will see that they will not forget themselves, and how you will be treated. I do not mention, O men, your frivolities, your follies and caprices, which place you lower than the mole or the tortoise, who wisely move along quietly and follow invariably their own natural instinct; but listen to me for a moment: You say of a goshawk if it be very swift-winged and swoops well down on a partridge, that it is a good bird; of a greyhound following a hare very close and catching it, that it is a first-rate dog; it is also quite right that you should say of a man who hunts the wild boar, brings it to bay, walks up to it and kills it with a spear, that he is a courageous man. But if you see two dogs barking at each other, provoke, bite, and tear one another to pieces, you say they are foolish creatures, and take a stick to part them. If any one should come and tell you that all the cats of a large country met in a plain in their thousands and tens of thousands, and that after they had squalled to their heartsʼ content they had fallen upon each other tooth and nail; that about ten thousand of them had been left dead on the spot and infected the air for ten leagues round with their evil-smelling carcasses; would you not say that it was the most disgraceful row you ever heard? And if the wolves acted in the same way, what a butchery would there be, and what howls would be heard! Now, if these two kind of animals were to tell you they love glory, would you come to the conclusion that this glory consists in their meeting together in such a way to destroy and annihilate their own species; and if you have come to such a conclusion, would you not laugh heartily at the folly of these poor animals? Like rational creatures, and to distinguish yourselves from those which only make use of their teeth and claws, you have invented spears, pikes, darts, sabres, and scimitars, and, in my opinion, very judiciously; for what could you have done to one another merely with your hands, except tearing your hair, scratching your faces, and, at best, gouging one anotherʼs eyes out; whilst now you are provided with convenient instruments for making large wounds and for letting out the utmost drop of your blood, without there being any fear of your remaining alive? But as you grow more rational from year to year, you have greatly improved the old fashion of destroying yourselves; you use certain little globes677 which kill at once, if they but hit you on the head or chest; you have other globes, heavier and more massive,678 which cleverly cut you in two or disembowel you, without counting those falling on your roof,679 breaking through the floors from the garret to the cellar, which they destroy, and blowing up your wife who is lying-in, and the child, the nurse, and the house as well. And yet this is glory, which delights in all this hurly-burly and mighty hubbub! You have also defensive arms, and according to the rules and regulations, when waging war, you should put on a suit of iron, no doubt a pretty becoming dress, which always puts me in mind of those four famous fleas, formerly shown by a cunning artist, a quack, who knew how to keep them alive in a glass phial; each of those little animals wore a helmet, their bodies were covered by a breastplate; they had vambraces, knee-pieces, and a spear at their side; their accoutrements were quite perfect, and thus they skipped and jumped about in their bottle. Fancy a man of the size of Mount Athos,680 and why not? Would a soul be puzzled to animate such a body, for it would have plenty of room to move about in? If such a manʼs sight were piercing enough to discover you somewhere upon earth, with your offensive and defensive arms, what do you think would be his opinion of a parcel of little marmosets thus equipped, and of what you call war, cavalry, infantry, a memorable siege, a famous battle? Shall I never hear any other sound buzz in my ears? Is the world only filled with regiments and companies? Has everything been changed to battalions and squadrons?—He takes a town, then a second, then a third; he wins a battle, two battles, he drives away the enemy, he conquers by sea, by land.—Do you say these things of one of you, or of a giant, a Mount Athos? There is a remarkable man amongst you, pale and livid,681 with not ten ounces of flesh on his bones, and who would be blown down by the least gust of wind, one would think, and yet he makes more noise than half-a-dozen men, and sets everything in a blaze; he has just now been fishing in troubled waters, and caught a whole island at once; in another place, it is true, he is beaten and pursued, but escapes into the bogs,682 and will hearken neither to peace nor to truce. He began betimes to show what he could do, and so severely bit his nurseʼs breast683 that the poor woman died of it; I know what I mean, and that is sufficient. To conclude: he was born a subject and is no longer one; on the contrary, he is now the master, and those whom he has overcome and brought under his yoke are harnessed to the plough and till the ground with might and main; those good people seem even afraid of being unyoked one day and of becoming free, for they have pulled out the thong and lengthened the handle of the whip of the man who drives them; they forget nothing that can increase their slavery; they let him cross the water so that he may get new vassals and acquire fresh territories; and to succeed in this he has, it is true, only to take his father and mother by the shoulders and throw them out of doors, and they aid him in this virtuous undertaking. The people on this side and that side of the water subscribe, and each pays his share, to render him every day more and more formidable to all; the Picts and the Saxons compel the Batavians to be silent, and the latter act in the same manner to the Picts and Saxons; they may all boast of being his humble slaves, as they wished to be. But what do I hear of certain personages who wear crowns? I do not mean counts or marquesses, who swarm on this earth, but princes and sovereigns. This man does but whistle, and they come at his call; they uncover as soon as they are in his anteroom, and never speak but when he asks them a question.684 Are these the same princes who cavil so much and are so precise about rank and precedence, and who spend whole months in regulating such questions whilst some Diet is assembled? What shall this new ruler685 do to reward so blind a submission, and to satisfy the high opinion they have of him? If a battle is to be fought, he must win it, and in person; if the enemy besieges a town, he must go raise the siege and drive him away with ignominy, unless the ocean be between him and the enemy;686 it is the least he can do to please his courtiers. Cæsar687 himself comes and swells their number; at least he expects important services from him; for either the “archon” and his allies will fail, which is more difficult than impossible to conceive, or, if he succeeds, and nothing resists him, he is ready with his allies, who are jealous of Cæsarʼs religion and greatness, to rush upon him, snatch away his eagle, and reduce him and his heir to the “fasces argent”688 and to his hereditary dominions. But there is no use saying anything more; they have all voluntarily given themselves up to the man whom they should perhaps have distrusted the most. Would Esop not have told them that “the feathered tribe of a certain country got alarmed and frightened at being near a lion, whose mere roar terrified them; they went to the animal, who persuaded them he would come to some arrangement, and take them under his protection. The end of it was that he gobbled them all up one after another.”

XIII.

OF FASHION.

(1.)IT is very foolish, and betrays what a small mind we have, to allow fashion to sway us in everything that regards taste, in our way of living, our health, and our conscience. Game is out of fashion, and therefore insipid, and fashion forbids to cure a fever by bleeding. This long while it has also not been fashionable to depart this life shriven by Theotimus; now none but the common people are saved by his pious exhortations, and he has already beheld his successor.689

(2.) To have a hobby is not to have a taste for what is good and beautiful, but for what is rare and singular, and for what no one else can match; it is not to like things which are perfect, but those which are most sought after and fashionable. It is not an amusement but a passion, and often so violent that in the meanness of its object it only yields to love and ambition. Neither is it a passion for everything scarce and in vogue, but only for some particular object which is rare, and yet in fashion.

The lover of flowers has a garden in the suburbs, where he spends all his time from sunrise till sunset. You see him standing there, and would think he had taken root in the midst of his tulips before his “Solitaire;” he opens his eyes wide, rubs his hands, stoops down and looks closer at it; it never before seemed to him so handsome; he is in an ecstasy of joy, and leaves it to go to the “Orient,” then to the “Veuve,” from thence to the “Cloth of Gold,” on to the “Agatha,” and at last returns to the “Solitaire,” where he remains, is tired out, sits down, and forgets his dinner; he looks at the tulip and admires its shade, shape, colour, sheen, and edges, its beautiful form and calix; but God and nature are not in his thoughts, for they do not go beyond the bulb of his tulip, which he would not sell for a thousand crowns, though he will give it to you for nothing when tulips are no longer in fashion, and carnations are all the rage. This rational being, who has a soul and professes some religion, comes home tired and half-starved, but very pleased with his dayʼs work; he has seen some tulips.690

Talk to another of the healthy look of the crops, of a plentiful harvest, of a good vintage, and you will find he only cares for fruit, and understands not a single word you say; then turn to figs and melons; tell him that this year the pear-trees are so heavily laden with fruit that the branches almost break, that there are abundance of peaches, and you address him in a language he completely ignores, and he will not answer you, for his sole hobby is plum-trees. Do not even speak to him of your plum-trees, for he only is fond of a certain kind, and laughs and sneers at the mention of any others; he takes you to his tree and cautiously gathers this exquisite plum, divides it, gives you one half, keeps the other himself, and exclaims: “How delicious! do you like it? is it not heavenly? You cannot find its equal anywhere;” and then his nostrils dilate, and he can hardly contain his joy and pride under an appearance of modesty. What a wonderful person, never enough praised and admired, whose name will be handed down to future ages! Let me look at his mien and shape whilst he is still in the land of the living, that I may study the features and the countenance of a man who, alone amongst mortals, is the happy possessor of such a plum.691

Visit a third, and he will talk to you about his brother collectors, but especially of Diognetes.692 He admits that he admires him, but that he understands him less than ever. “Perhaps you imagine,” he continues, “that he endeavours to learn something of his medals, and considers them speaking evidences of certain facts that have happened, fixed and unquestionable monuments of ancient history. If you do, you are wholly wrong. Perhaps you think that all the trouble he takes to become master of a medallion with a certain head on it is because he will be delighted to possess an uninterrupted series of emperors. If you do, you are more hopelessly wrong than ever. Diognetes knows when a coin is worn, when the edges are rougher than they ought to be, or when it looks as if it had been newly struck; all the drawers of his cabinet are full, and there only is room for one coin; this vacancy so shocks him that in reality he spends all his property and literally devotes his whole lifetime to fill it.”

“Will you look at my prints?” asks Democedes,693 and in a moment he brings them out and shows them to you. You see one among them neither well printed nor well engraved, and badly drawn, and, therefore, more fit on a public holiday to be stuck against the wall of some house on the “Petit-Pont” or in the “Rue Neuve”694 than to be kept in a collection. He allows it to be badly engraved and worse drawn; but assures you it was done by an Italian who produced very little, and that hardly any of these prints have been struck off, so that he has the only one in France, for which he paid a very heavy price, and would not part with it for the very best print to be got. “I labour under a very serious affliction,” he continues, “which will one day or other cause me to give up collecting engravings; I have all Callotʼs etchings,695 except one, which, to tell the truth, so far from being the best, is the worst he ever did, but which would complete my collection; I have hunted after this print these twenty years, and now I despair of ever getting it; it is very trying!”

Another man criticises those people who make long voyages either through nervousness or to gratify their curiosity; who write no narrative or memoirs, and do not even keep a journal; who go to see and see nothing, or forget what they have seen; who only wish to get a look at towers or steeples they never saw before, and to cross other rivers than the Seine or the Loire; who leave their own country merely to return again, and like to be absent, so that one day it may be said they have come from afar; so far this critic is right and is worth listening to.

But when he adds that books are more instructive than travelling, and gives me to understand he has a library, I wish to see it. I call on this gentleman, and at the very foot of the stairs I almost faint with the smell of the Russia leather bindings of his books. In vain he shouts in my ears, to encourage me, that they are all with gilt edges and hand-tooled, that they are the best editions, and he names some of them one after another, and that his library is full of them, except a few places painted so carefully that everybody takes them for shelves and real books, and is deceived. He also informs me that he never reads nor sets foot in this library, and now only accompanies me to oblige me. I thank him for his politeness, but feel as he does on the subject, and would not like to visit the tan-pit which he calls a library.

Some people immoderately thirst after knowledge, and are unwilling to ignore any branch of it, so they study them all and master none; they are fonder of knowing much than of knowing some things well, and had rather be superficial smatterers in several sciences than be well and thoroughly acquainted with one. They everywhere meet with some person who enlightens and corrects them; they are deceived by their idle curiosity, and often, after very long and painful efforts, can but just extricate themselves from the grossest ignorance.

Other people have a master-key to all sciences, but never enter there; they spend their lives in trying to decipher the Eastern and Northern languages, those of both the Indies, of the two poles, nay, the language spoken in the moon itself. The most useless idioms, the oddest and most hieroglyphical-looking characters, are just those which awaken their passion and induce them to study; they pity those persons who ingenuously content themselves with knowing their own language, or, at most, the Greek and Latin tongues. Such men read all historians and know nothing of history; they run through all books, but are not the wiser for any; they are absolutely ignorant of all facts and principles, but they possess as abundant a store and garner-house of words and phrases as can well be imagined, which weighs them down, and with which they overload their memory, whilst their mind remains a blank.

A certain citizen loves building, and had a mansion erected so handsome, noble, and splendid that no one can live in it.696 The proprietor is ashamed to occupy it, and as he cannot make up his mind to let it to a prince or a man of business, he retires to the garret, where he spends his life, whilst the suite of rooms and the inlaid floors are the prey of travelling Englishmen and Germans, who come to visit it after having seen the Palais-Royal, the palace L ... G ...697 and the Luxembourg. There is a continual knocking going on at these handsome doors, and all visitors ask to see the house, but none the master.

There are other persons who have grown-up daughters, but they cannot afford to give them a dowry, nay, these girls are scarcely clothed and fed; they are so poor that they have not even a bed to lie upon nor a change of linen. The cause of their misery is not very far to seek; it is a collection crowded with rare busts, covered with dust and filth, of which the sale would bring in a goodly sum; but the owners cannot be prevailed upon to part with them.

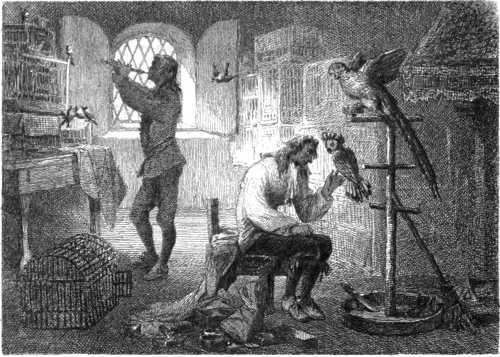

Diphilus is a lover of birds, he begins with one and ends with a thousand; his house is not enlivened, but infested by them; the courtyard, the parlour, the staircase, the hall, all the rooms, and even the private study are so many aviaries; we no longer hear warbling, but a perfect discord; the autumnal winds and the most rapid cataracts do not produce so shrill and piercing a noise; there is no hearing one another speak but in those apartments set apart for visitors, where people will have to wait until some little curs have yelped, before there is a chance of seeing the master of the house. These birds are no longer an agreeable amusement for Diphilus, but a toilsome fatigue, for which he can scarcely find leisure; he spends his days—days which pass away and never come back—in feeding his birds and cleaning them; he pays a man a salary698 for teaching his birds to sing with a bird-organ, and for attending to the hatching of his young canaries. It is true that what he spends on the one hand he spares on the other, for his children have neither teachers nor education. In the evening, worn out by his hobby, he shuts himself up, without being able to enjoy any rest until his birds have gone to roost, and these little creatures, on which he dotes only for their song, have ceased to warble. He dreams of them whilst asleep, and imagines he is himself a tufted bird, chirping on his perch; during the night he even fancies he is moulting and brooding.

Who can describe all the different kinds of hobbies? Can you imagine when you hear a certain person speak of his “Panther Cowry,” his “Pen Shell,” and his “Music Shell,”699 and brag of them as something very rare and marvellous, that he intends to sell these shells? Why not? He has bought them for their weight in gold.

Another is an admirer of insects, and augments his collection every day; in Europe he is the best judge of butterflies, and has some of all sizes and colours.700 What an unfortunate time you have chosen to pay him a visit! He is overwhelmed with grief, and in a fearful temper, which he vents on his family; he has suffered an irreparable loss; draw near him and observe what he shows you on his finger; it is a caterpillar, but such a caterpillar, lifeless, and but just expired.

(3.) Duelling is the triumph of fashion, which it sways tyrannically and most conspicuously. This custom does not allow a coward to live, but compels him to go and be killed by a man of more valour than himself, and to be mistaken for a man of courage. The maddest and most absurd action has been called honourable and glorious; it has been sanctioned by the presence of kings; in some cases it has even been considered a sort of duty to countenance it; it has decided the innocence of some persons,701 and the truth or falsity of certain accusations of capital crimes; it was so deeply rooted in the opinion of all nations, and had obtained such a complete possession of the feelings and minds of men, that to cure them of this folly has been one of the most glorious actions of the greatest of monarchs.702

(4.) Some persons were formerly in high repute for commanding armies, for diplomacy, for pulpit eloquence, or for poetry, and now they are no longer fashionable. Do certain men degenerate from what they formerly were, and have their merits become antiquated, or is our liking for them worn out?

(5.) A fashionable man is not long the rage, for fashions are ephemeral; but if he happens to be a man of merit, he is not totally eclipsed, but something or other of him will still survive; he is as estimable as he formerly was, but only less esteemed.

Virtue is fortunate enough to be able to do without any help, and can exist without admirers, partisans, and protectors; lack of support and approbation does not harm it, but, on the contrary, strengthens, purifies, and perfects it; whether in or out of fashion, it is still virtue.

(6.) If you tell some men, and especially the great, that a certain person is virtuous, they will say to you, “they trust he may long remain so;” that he is very clever, and above all, agreeable and entertaining, they will answer you, “that it is so much the better for him;” that he is a man of culture and knows a great deal, they will ask you “what oʼclock it is, or what sort of weather we have?” But if you inform them that a Tigellinus703 has been gulping down a glass of brandy,704 and, wonderful to relate, that he has repeated this several times during his repast, they will ask where he is, and tell you to bring him with you the next day, or that same evening, if possible. We bring him with us, and that very man, only fit for a fair or to be shown for money, is treated by them as a familiar acquaintance.

(7.) Nothing brings a man sooner into fashion and renders him of greater importance than gambling;705 it is almost as good as getting fuddled.706 I should like to see any polished, lively, witty gentleman, even if he were Catullus himself or his disciple,707 dare to compare himself with a man who loses eight hundred pistoles708 at a sitting.

(8.) A fashionable person is like a certain blue flower which grows wild in the fields, chokes the corn, spoils the crops, and takes up the room of something better; it has no beauty nor value but what is owing to a momentary caprice, which dies out almost as soon as sprung up. To-day it is all the rage, and the ladies are decked with it; to-morrow it is neglected and left to the common herd.709

A person of merit, on the contrary, is a flower we do not describe by its colour, but call by its name, which we cultivate for its beauty or fragrance, such as a lily or a rose; one of the charms of nature, one of those things which beautify the world, belonging to all times, admired and popular for centuries, valued by our fathers, and by us in imitation of them, and not at all harmed by the dislike or antipathy of a few.

(9.) Eustrates is seated in his small boat, delighted with the fresh air and a clear sky; he is seen sailing with a fair wind, likely to last for some time, but a lull comes on all of a sudden, the sky becomes overcast, a storm bursts forth, the boat is caught by a whirlwind, and is upset. Eustrates rises to the surface of the waters and exerts himself; it is to be hoped he will at least save himself and get hold of the boat; but another wave sinks him, and he is considered lost: a second time he appears above the water, and hope revives, when a billow all of a sudden swallows him up; he is never more seen again, he is drowned.

(10.) Voiture and Sarrazin710 just suited the age they lived in, and appeared at the right time, when it seems they were expected; if they had not made such haste they would have come too late; and I question if, at present, they would have been what they were then. Light conversation, literary society, delicate raillery, lively and familiar epistolary interchange, and a select circle of friends, where intelligence was the only passport of admittance, have all disappeared. To say that these authors would have revived them is too much; all I can venture to admit in favour of their intellect is, that perhaps they might have excelled in another way. But the ladies of the present time are either devotees, coquettes, fond of gambling, or ambitious, and some of them all these together; court favour, gambling, gallants, and spiritual directors, have taken their places, and they defend them against men of culture.711

(11.) A coxcomb, who makes himself ridiculous as well, wears a tall hat, a doublet with puffs on the shoulders, breeches with ribbons or tags, and jackboots; at night he dreams what he shall do to be taken notice of the following day. A wise man leaves the fashion of his clothes to his tailor; it shows as much weakness to run counter to the fashion as to affect to follow it.

(12.) We blame a fashion that divides the shape of a man into two equal parts, and takes one of it for the waist, whilst leaving the other for the rest of the body; we condemn the fashion of making of a ladyʼs head the basis of an edifice of several heights, the build and shape of which change according to fancy; which removes the hair from the face, though Nature designed it to adorn it; and ties it up and makes it bristle so that the ladies look like Bacchantes; this fashion seems to have been intended to make the fair sex change its mild and modest air for one much more haughty and bold. People exclaim against certain fashions as ridiculous; but they adopt them as long as they last, to adorn and embellish themselves, and they derive from them all the advantages they can expect, namely, to please. Methinks the inconstancy and fickle-mindedness of men is to be admired; for they successively call agreeable and ornamental things directly opposed to one another; they use in plays and masquerades those same dresses and ornaments which, until then, were considered as denoting gravity and sedateness; a short time makes all the difference.712

(13.) N ... is wealthy; she eats and sleeps well; but the fashion of head-dresses alters, and whilst she does not think anything at all about it, and believes herself quite happy, her head-dress has quite grown out of fashion.

(14.) Iphis attends church, and sees there a new-fashioned shoe; he looks upon his own with a blush, and no longer believes he is well dressed. He only comes to hear mass to show himself, but now he refuses to go out, and keeps his room all day on account of his foot. He has a soft hand, which he preserves so by scented paste, laughs often to show his teeth, purses up his mouth, and is perpetually smiling; he looks at his legs and surveys himself in the glass, and no man can have a better opinion of his personal appearance than he has; he has adopted a clear and delicate voice, but fortunately lisps;713 he moves his head about and has a sort of sweetness in his eyes which he does not forget to use to set himself off; his gait is indolent, and his attitudes are as pretty as he can contrive them; he sometimes rouges his face, but not very often, and does not do so habitually. In truth, he always wears breeches and a hat, but neither earrings nor a pearl necklace; therefore I have not given him a place in my chapter “Of Women.”

(15.) Those very fashions which men so willingly adopt to adorn themselves are apt to be laid aside when their portraits are taken, as if they felt and foresaw how crude714 and ridiculous these would look when they had lost the bloom and charm of novelty; they prefer to be depicted with some fancy ornaments, some imaginary drapery, just as it pleases the artist, and which often are as little suited to their air and face as they recall their character and personage. They affect strained or indecent attitudes, harsh, uncultivated, and foreign manners, which transform a young abbé into a swaggerer, and a magistrate into a swashbuckler, a Diana into a woman of the town, an amazon or a Pallas into a simple and timid woman, a Laïs into a respectable girl, and a Scythian, an Attila,715 into a just and magnanimous prince.

Such is our giddiness, that one fashion has hardly destroyed another, when it is driven away by a newer one, again to make way for its successor, which will not be the last. Whilst these changes are going on, a century elapses, and all these gewgaws are ranked amongst things of the past, and exist no longer. Then the oldest fashion becomes again the most elegant, and charms the eye the most, it pleases as much in portraits as the sagum or the Roman dress on the stage, as a long black veil, an ordinary veil, and a tiara716 do on our hangings and our pictures.

Our fathers have transmitted to us the history of their lives as well as a knowledge of their dresses, their arms,717 and their favourite ornaments; a benefit for which we can make no other return than by doing our posterity the same service.

(16.) Formerly a courtier wore his own hair, breeches, and doublet, as well as large canions,718 and was a freethinker;719 but this is no longer becoming; now he wears a wig, a tight suit, plain stockings, and is devout. All this because it is the fashion.

(17.) Any man who, after having dwelt for a considerable time at court, remains devout, and contrary to all reason, narrowly escapes being thought ridiculous, can never flatter himself with becoming the fashion.

(18.) What will not a courtier do for the sake of advancing his interests? Rather than not advance them he will turn pious.720

(19.) The colours are all prepared, and the canvas is stretched, but how shall I fix this restless, giddy, and variable man, who adopts so many thousand different shapes? I depict him as devout, and I think I have caught his likeness; but I have missed it, and he is already a freethinker. Let him remain even in this bad position, and I shall succeed in portraying his irregularity of heart and mind so that he will be known; but another fashion is in vogue, and again he becomes devout.

(20.) A man who thoroughly knows the court is well aware what virtue and what piety is;721 there is no imposing upon him.

(21.) To neglect going to vespers as obsolete and not fashionable; to keep oneʼs place for morning service; to know all the ins and outs of the chapel at Versailles, and who sits in the seats next722 to the royal tribune, and what is the best place where a man can be seen or remain unobserved; to be thinking at church of God and business; to receive visits there; to order people about and send them on messages or wait for answers; to trust more to the advice of a spiritual director than to the teachings of the Gospel; to derive all sanctity and notoriety from the reputation of our director; to despise all people whose director is not fashionable, and scarcely allow them to be in a state of salvation; to like the word of God only when preached at home or from the mouth of our own director; to prefer hearing a mass said by him to any other mass, and the sacraments administered by him to any others, which are considered of less value; to satiate ourselves with mystical books, as if there were neither Gospels, Epistles of the Apostles, nor morals of the fathers; to read or speak a jargon unknown in the early centuries;723 to be very circumstantial in amplifying the sins of others and in palliating our own; to enlarge on our own sufferings and patience; to lament our small progress in heroism as a sin; to be in a secret alliance with some persons against others; to value only ourselves and our own set; to suspect even virtue itself; to enjoy and relish prosperity and favour, and to wish to keep them only for ourselves; never to assist merit; to make piety subservient to ambition; to obtain our salvation through fortune and dignities; these are, at least in our days, the greatest efforts of the piety of this age.

A pious person724 is one who, under an atheistical king, would be an atheist.

(22.) Devout people know no other crime but incontinence, or, to speak more exactly, the scandal and appearance of incontinence. If Pherecides passes for a man who is cured of his fondness for women, or Pherenicia for a wife who is faithful to her husband, they are quite satisfied; allow these devotees to continue a game that finally will be their undoing; it is their business to ruin their creditors, to rejoice at the misfortunes of other people and take advantage of it, to idolise the great, to despise their inferiors, to get intoxicated with their own merit, to pine away with vexation, to lie, slander, intrigue, and do as much harm as they can. Would you like them to usurp the functions of those honest men725 who avoid pride and injustice as well as the more latent vices?

(23.) When a courtier shall be humble, divested of pride and ambition, cease to advance his own interests by ruining his rivals, be just and relieve the misery of his vassals, pay his creditors, be neither a knave nor a slanderer, shall abandon luxurious feasting and unlawful amours, pray not only with his lips, and even when the prince is not present, shall not be morose and inaccessible, not show an austere countenance and a sour mien, shall not be lazy and buried in thought, reconcile a multiplicity of employments by conscientious application, shall be able and willing to devote his whole mind and all his attention to those great and arduous affairs which especially concern the welfare of the people and of the entire state; when his character shall make me afraid of mentioning him in this paragraph, and his modesty prevent him from knowing himself, if I should not give his name; then I shall say of such a man that he is devout, or rather that he is a man given to this age as an example of sincere virtue as well as to detect hypocrites.726

(24.) Onuphriusʼ bed727 has only grey serge valances, but he sleeps on flock and down; he also wears plain but comfortable clothes, I mean, made of a light material in summer, and of very soft cloth in winter; his body-linen is very fine, but he takes very good care not to show it; he does not call out for his “hair-shirt and scourge,”728 for then he would show himself in his true colours, as a hypocrite, whilst he intends to pass for what he is not, for a religious man; however, he acts in such a way that people believe, without his telling it them, that he wears a hair-shirt and scourges himself. Several books lie about his apartments, such as the “Spiritual Fight,” the “Inward Christian,” the “Holy Year;”729 his other books are under lock and key; if he goes along the streets and perceives from afar a man to whom he ought to seem devout, downcast looks, a slow and demure gait, and a contemplative air are at his command; he plays his part. If he enters a church, he observes whose eyes are upon him, and accordingly kneels down and prays, or else, never thinks of kneeling down and praying; if he sees an honest man and a man of authority approach him, by whom he is sure to be perceived, and who, perhaps, may hear him, he not only prays but meditates, has outbursts of devotion, and sighs aloud; but as soon as this honest man is gone, he becomes calm, and does not say a single word more. Another time he enters a chapel, rushes through the crowd, and chooses a spot to commune with himself, and where everybody may see how he humbles himself;730 if he hears any courtiers speaking or laughing loud, and behave in chapel more boisterously than they would in an ante-chamber,731 he makes a greater noise than they to silence them, and returns to his meditations, in which he always disdainfully compares those persons to himself, to his own advantage. He avoids an empty church where he could hear two masses one after another, as well as a sermon, vespers, and compline, with no one between God and himself, without any other witnesses, and without any one thanking him for it; but he likes his own parish, and frequents those churches where the greatest number of people congregate, for there he does not labour in vain and is observed. He chooses two or three days of the year to fast in or to abstain from meat, without any occasion; but at the end of the winter he coughs; there is something wrong with his chest, he is more or less splenetic,732 and feels very feverish; people entreat him, urge him, and even quarrel with him to compel him to break his fast as soon as it has begun, and he obeys them out of politeness. If Onuphrius is chosen as an umpire by relatives who have quarrelled, or in a lawsuit amongst members of one and the same family, he always takes the side of the strongest, I mean the wealthiest, and cannot be convinced that any person of property can ever be in the wrong. If he is comfortable at the house of a rich man whom he can deceive, whose parasite he is, and from whom he may derive great advantages, he never cajoles his patronʼs wife, nor makes the least advances to her, nor declares his love;733 but rather avoids her, and will leave his cloak behind,734 unless he is as sure of her as he is of himself; still less will he make use of devotional735 cant to flatter and seduce her, for he does not employ it habitually, but intentionally, when it suits him, and never when it would only make him ridiculous. He knows where to find ladies more sociable and pliable than his friendʼs wife; and very seldom absents himself from these ladies for any length of time, if it were only to have it publicly stated that he has gone into religious retirement; for who can doubt the truth of this report, when people see him reappear quite emaciated, like one who has, not spared himself?