Beyond the white Râs el-Nâkûra, the ancient Scala Tyriorum, and Râs el-Abyad, the Promontorium Album of Pliny, we sight a low headland on which lies the poor little town of Sûr, with a ruined church of the Crusaders, ruins of their fortifications, and a lighthouse. This was the ancient seaport of Tyre, once situated on two islands, but connected with the mainland by an embankment built by Alexander during his famous siege (332 B.C.).

Farther on we pass the mouth of the Nahr el-Lîtânî (p. 483), here called Nahr el-Kâsimîyeh, and obtain a fine view of the coast-region in front of Lebanon; to the E. rise Jebel er-Rihân and Tômât Nîhâ (6070 ft.; ‘twins of Nîhâ’), snow-capped in winter, and to the N.E. the distant Jebel Sannîn (p. 483).

Beyond Sarafant (ancient Zarpath or Sarepta) opens the broad bay of Saida, formerly Sidon, the oldest and, next to Tyre, greatest port of the Phœnicians, now girdled by rich vegetation.

Passing the mouth of the Nahr el-Auwâlî (ancient Bostrenus) and the Râs er-Rumeileh, the N. limit of the bay of Saida, we come to the far-projecting Râs ed-Dâmûr and the Nahr ed-Dâmûr, the ancient Tamyras, which in winter is one of the most copious rivers in the Lebanon region. Near Beirut begin the mulberry and olive groves and the vineyards of the fertile coast-plain.

We round the reddish hills of Râs Beirût (p. 483), with the pigeons’ grottoes and lighthouse, and enter Beirut harbour (p. 481).

73. From Jaffa to Jerusalem.

54½ M. Railway. Two trains daily in 3 hrs. 40 min. (1st cl. 70½ pias.; 2nd, inferior to good Engl. 3rd, 25 pias.). Railway rates of exchange: 1 mejidieh = 20 pias.; 20 fr. = 94 pias.; £ 1 = 124 pias.; £ 1 Turkish = 108 pias. (comp. p. 536).

Jaffa, see p. 467. The train skirts the orchards around Jaffa (with Sarona on the left) and turns to the S.E. through the plain of Sharon (p. 468), following the depression of the Wâdi Miserâra. On the right is the agricultural colony of the Alliance Israélite. To the E. rise the bluish hills of ancient Judaea.

12 M. Lydda, Arabic Ludd, Old Test. Lod, Gr.-Rom. Diospolis, was severed from Samaria by the Maccabees (p. 472) in 145 B.C. and annexed to Judæa.

14 M. Er-Ramleh (accommodation at the Franciscan convent; pop. exceeding 7000, incl. 2500 Christians), founded by the Omaiyades (p. 485) in 716, was the Ramula of the era of the Crusades, when it was even more important than Jerusalem. The chief sight is the *Minaret of the oldest mosque (Jâmi el-Abyad, ‘white mosque’), famed also for its view. It was erected by En-Nâsir (p. 448) in 1318, in a style recalling the Romanesque transition buildings of the Crusaders (p. 474), but has lost its original summit.

The train crosses the Jerusalem road and runs to the S. through marshy flats to (18 M.) the village of Nâaneh. At some distance from the railway Akir, once Ekron, one of the five chief cities of the Philistines (p. 466), lies on the right (W.), and on the left (E.) are the famous ruins of Tell Jezer, mentioned in the letters found at Tell el-Amarna (p. 456), originally the Canaanitish (Phœnician) city of Gezer (a drive of 1 hr. from Er-Ramleh).

24½ M. Sejed. Soon turning to the E., we ascend the Wâdi es-Sarâr (‘valley of Sorek’, Judg. xvi. 4), which beyond (31 M.) Deir Abân narrows to a wild rocky gorge.

47½ M. Bittir, the ancient Baither or Bethar, was heroically defended against the Romans during the revolt of Bar Cochba (p. 472). The train then ascends in the Wâdi el-Werd (‘valley of roses’) and crosses the plain of El-Bukeia to (54½ M.) Jerusalem.

Jerusalem.—The Station (2451 ft.; see Pl. C, 9) lies ¾ M. to the S. of the Jaffa Gate; carr. into the town 2–5 fr., according to the season.

Hotels. *Fast’s Hotel (Pl. a; C, 4, 5), Jaffa Road; Grand New Hotel (Pl. c; D, 5), New Bazaar; Hôt. Hughes (Pl. d; C, 4), Jaffa Road; Olivet House (Pl. e; C, 2); Hôt. Kaminitz (Pl. b; C, 4), Jaffa Road. Pension at all 12–15 (out of season 8–10) fr. per day. Agreement advisable. Wine of the country 1–2, French wine from 3 fr. a bottle.

Hospices. Prussian Johanniter-Hospiz (Pl. g; F, 4), pens. 5 fr.; German Catholic Hospice St. Paulus (Pl. h; E, 2), outside the Damascus Gate; Austrian (Pl. i; F, 3), Via Dolorosa; Casa Nuova (Pl. k; D 4, 5), of the Franciscans; all good, pens. 5–8 fr.

Restaurants. Deutsche Bierhalle, Jaffa Road; Lendhold (brewery), in the German Temple colony.

Post Offices. Turkish (Pl. C, 5: with the International Telegraph), outside the Jaffa Gate; French (Pl. C, 5), adjoining it; German (Pl. D, 5), etc.

Tourist Offices. Thos. Cook & Son, inside Jaffa Gate; Clark, Hamburg-American Line, Dr. Benzinger (North German Lloyd), N. Tadros, all in Jaffa Road.

Carriages at the Jaffa Gate. Drive ¼ hour, ½ mejidieh. Excursions are best arranged for by tourist-agent or landlord of hotel. So also Horses, half-day 5, whole day 8 fr.; donkey per day 4–5, half-day 2–3 fr.

Consulates. British (Pl. 5; A, 1), H. E. Satow.—United States (Pl. 13; E, 5): consul, W. Coffin.

Banks. Anglo-Palestine Co. (Pl. 1; E, 6), opposite the citadel; Crédit Lyonnais (Pl. 2; D, 5) and Banque Ottomane (Pl. D, 5), Jaffa Road; German Palaestina-Bank (Pl. 3; D, 5), inside Jaffa Gate.

Photographs. The best are those of the American Colony, of Bonfils of Beirut, and (coloured) of the Photoglob of Zürich, to be obtained from Vester (American Colony Store), Boulus Meo, Sfeir, and Shammas, all in the Grand New Hotel; A. Attallah, at the Bâb el-Jedîd; Salman & Co., Jaffa Road.—Other favourite Souvenirs of Jerusalem are carved olive-wood and mother-of-pearl objects, in which there is a brisk trade; the largest choice is to be found in the square in front of St. Sepulchre’s, but half at most of the price asked should be offered; higher class work is best purchased at the shops mentioned above.

Churches, convents, missions, schools, etc. abound (see Baedeker’s Palestine & Syria). Among them may be mentioned the Collegiate Church of St. George (with the Bishop’s House; services at 9 a.m. and 4.30 p.m.), to the N. of the town; Christ Church (Pl. E, 6; services at 10 a.m. and 4 p.m.); St. Paul’s (Pl. C, 1, 2; Arabic services at 9.30 a.m. and 3 p.m.).

Two Days (when time is limited). 1st. Forenoon, Mt. of Olives (p. 479), Kidron and Hinnom Valleys (p. 480); afternoon, Church of the Holy Sepulchre (p. 474), Mûristân (p. 475), and Zion (p. 473).—2nd. Forenoon, Haram esh-Sherîf (p. 476); afternoon, excursion to Bethlehem (p. 480).

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is open before 11.30 and after 3; a forenoon visit may usually be prolonged by giving a fee to the Moslem custodian (1 fr.).

Leave to visit the Haram esh-Sherîf must be obtained from the Turkish authorities through the visitor’s consulate (see above). He is then escorted by a Turkish soldier and usually by a cavass of the consulate also. The cavass receives 8–10 fr., or 4–5 fr. from each member of a party, which covers all fees and outlays. On Fridays and during the Moslem festival of Nebi-Mûsâ (Wed. of Holy Week to Easter Mon.) the mosque is closed to strangers.

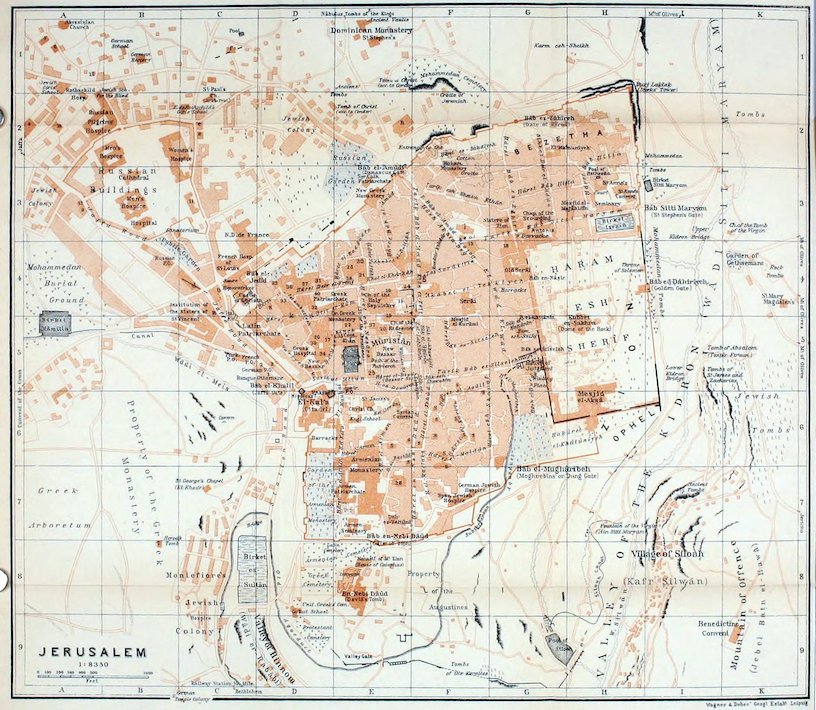

Key to Plan of Jerusalem. Banks, see above.—Bazaars, Old (Sûks) and New, F 5; E 5.—Churches. Christ Church (English), E 6; Church of the Redeemer (German Prot.), E 5; Holy Sepulchre, E 4; St. Anne’s, H 3; St. George’s (English), with Bishop’s House, a little to the N. of E 1; St. Mary’s, K 3; St. Mary Magdalen’s, K 4; St. Paul’s (Arab.-Prot.), C 1, 2.— Consulates, see above.—Monasteries. Abraham’s (Greek), Pl. 19, E 4, 5; Abyssinian, Pl. 14, E 4; Armenian Catholic, Pl. 15, F 4; Coptic, Pl. 16, E 4; Gethsemane, Pl. 20, E 5; Greek (Great), D E 4, 5; Panagia (Greek), Pl. 21, E 4; Panagia Melæna (Gr.), Pl. 22, E 5; St. Basil (Gr.), Pl. 23, D 4; St. Caralombos (Gr.), Pl. 24, E 4; St. Catharine (Gr.), Pl. 25, E 4; St. Demetrius (Gr.), Pl. 26, D 5; St. George’s (Coptic), Pl. 17, D 5; St. George’s (Greek), Pl. 27 & 28, D 4 & E 7; St. John the Baptist’s (Gr.), Pl. 29, E 5; St. John Euthymius (Gr.), Pl. 30, E 4; St. Michael’s (Gr.), Pl. 31, D 4; St. Nicholas (Gr.), Pl. 32, D 4; St. Salvator’s (Latin), Pl. 36, D 4; St. Stephen’s (Dominican), E 1; St. Theodore’s (Greek), Pl. 33, D 4.—Mosques. El-Aksâ, H 5, 6; Kubbet es-Sakhra (Dome of the Rock), H 4, 5; Sîdni Omar, Pl. 37, E 5.—Synagogues (indicated by the letter ‘S’ on the Plan), many, E, F 5–7.

Jerusalem (Hebrew Yerushalayim, Gr. and Lat. Hierosolyma, Arabic El-Kuds) lies in 31°46′ N. lat. and 35°13′ E. long., on an arid limestone plateau (cold in winter) which rises in the form of a peninsula from the Kidron Valley (Wâdi Sitti Maryam, ‘Mary’s Valley’), on the E., and from the Valley of Hinnom (Wâdi er-Rabâbi), on the S. side. The narrow E. height (2441 ft.), the ancient Temple Hill, is separated from the W. hill, that of the old Upper Town (2550 ft.), by a depression, now very slight, called Tyropoeon (‘dung valley’) by Josephus, the Jewish historian. Still higher is the N.W. angle of the present town (2591 ft.).

The population is estimated at 70,000, of whom 45,000 are Jews, living mostly on alms bestowed by the charitable institutions of their European co-religionists; of the 15,000 Christians nearly half are Syrians of the Greek orthodox faith; the Moslems number about 10,000. In spring, especially at the time of the Greek Easter, the town is flooded with pilgrims, the majority being Russians. As a centre of the three chief religions of the world, Jerusalem has quite a religious atmosphere and is historically a city of overwhelming interest, but its tranquillity is sadly marred by the dissensions and jealousies of its numerous religious communities. Careful and patient study alone will reveal to the traveller something of the departed glory of the venerable capital of the Jewish empire.

History. From the tablets of Tell el-Amarna (p. 456) it appears that Urusalim was the capital of a small principality dependent on Egypt about 1400 B.C. When the Israelites under David conquered the town in the 11th cent. (2 Sam. v. 6–10) it was the chief stronghold of the Jebusites, a Canaanitish tribe. David made it his residence and built a castle known as the City of David. His son Solomon, with the aid of Phœnician artificers, afterwards built his palace and the Temple of Jehovah on Mt. Zion (the E. hill). On the bi-partition of the kingdom after his death Jerusalem became the capital of Judah. The kingdom of Israel in N. Palestine was subjugated by the Assyrians in 722 B.C., and in 597 Jerusalem, under Jehoiachin, shared a like fate at the hands of Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. In 586 the revolt under Zedekiah led to the destruction of the city. On the return of the Jews from captivity in 538 the city and Temple were gradually rebuilt, and the new town-wall was completed in 444. On the death of Alexander the Great in 323 Jerusalem fell into the hands of the Ptolemies (p. 433) and often suffered severely from conflicts with the Diadochi of Syria. The last royal dynasty, that of the Maccabees (167–63), was overthrown by the Romans when Pompey conquered the city. As the residence of Herod the Great (37–4 B.C., according to the accepted chronology), in the last year of whose reign Christ was born, Jerusalem prospered anew. A new palace in the Roman style was erected at the N.W. angle of the upper town, and the rebuilding of the Temple was begun. But a revolt of the Zealots, or Jewish national party, led to embittered struggles with the Romans in 67 A.D., with the result that Jerusalem was stormed by Titus in 70, the Temple burned down, and the city was completely destroyed as Carthage had once been. Another rising of the Jews under Trajan (117) extended as far as the Cyrenaica (comp. p. 413) in N. Africa. On the ruins of the city, on a site almost coinciding with that enclosed by the present city-walls, Emp. Hadrian erected the new pagan colony of Ælia Capitolina, from which, after the last revolt, that of Bar Cochba (132–5), Jews were excluded.

The modern history of Christian Jerusalem begins with the building of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre by Emp. Constantine (about 326–36). Pilgrims soon flocked to the holy places, and in 570 there were already hospices with 3000 beds for their use. In 614 the Persians under Chosroes II. (p. 485) sacked the city, but when it was captured by caliph Omar in 637 it was treated with clemency, being regarded as a sacred place by Moslems as well as by Christians. In 691 began the erection of the famous Dome of the Rock, on the sacred rock (p. 477), the site of the ancient Jewish Temple, the greatest sanctuary of Islam after the Kaaba of Mecca. Jerusalem fell into the hands of the Egyptian Fatimites in 969, but was wrested from them by the Seljuks in 1077. It was chiefly the maltreatment of the Christian pilgrims by the Seljuks that gave rise to the First Crusade. In 1099 the Crusaders conquered Jerusalem, which under Godfrey de Bouillon (d. 1100) became the capital of the Christian kingdom of Jerusalem. The city was retaken by Saladin in 1187, but in 1229 was voluntarily ceded by Melik el-Kâmil to Emp. Frederick II. Lastly, in 1244, it was stormed by the Kharezmians, and has been under Moslem rule ever since.

Books. Among the best of the numerous works on Jerusalem are Barclay’s ‘City of the Great King’, Besant & Palmer’s ‘Jerusalem, the City of Herod and Saladin’ (5th ed., London, 1908), Warren’s ‘Underground Jerusalem’ (London, 1876), and Wilson & Warren’s ‘Recovery of Jerusalem’ (London, 1871). Miss A. Goodrich-Freer’s ‘Inner Jerusalem’ (1904), Laurence Hutton’s ‘Literary Landmarks of Jerusalem’, and C. R. Conder’s ‘The City of Jerusalem’ (London, 1909) also may be mentioned.

The *Old Town is enclosed by a *Wall of the 13–14th cent., restored by Suleiman the Great (p. 542) in 1537–41; it is 40 ft. high and about 2½ M. long. The two main streets lead to the W. from the Jaffa Gate (Pl. D, 5, 6; Arabic Bâb el-Khalîl), and N. from the handsome Damascus Gate (Pl. D, 5, 6; Bâb el-Amûd) respectively. They divide the town into four quarters, to the N.W. the Greek-Frank, S.W. the Armenian, S.E. the Jewish, and N.E. the Moslem. The streets are crooked, often vaulted over, and, in the Jewish quarter especially, very dirty. All the houses have rain-water cisterns, besides which there are several reservoirs.

The Jaffa Suburb, situated to the N.W., is the most important, in style the most European. It is the chief seat of the European or ‘Frank’ inhabitants and contains the consulates, several churches, and the extensive Russian Buildings (Pl. A-C, 2, 3).—Outside the Gate of Zion (Pl. E, 7, 8; Bâb en-Nebi Dâûd, ‘gate of the prophet David’), but originally within the town-walls, lies the so-called Zion Suburb. It contains the Christian cemeteries, the German Benedictine monastery Dormitio Sanctae Mariae (Pl. E, 8; ‘death-sleep of Mary’), with the new Church of St. Mary, and the now Mohammedan buildings of En-Nebi Dâûd (Pl. E, 8; with ‘David’s Tomb’ and the ‘Room of the Last Supper’). Near the railway-station (p. 470) is the substantial German Temple Colony (comp. p. 468).

We begin our visit to the old town at the Jaffa Gate, a busy centre of traffic, to which the road from the station leads (p. 480). To the S.E. of the gate, and partly on the site of Herod’s palace, rises the citadel El-Kala (Pl. D, 6; 14th and 16th cent.); the N.E. tower probably corresponds to the Phasaël Tower of the time of Herod.

David Street, one of the chief business streets, under different names (Sueikat Allân, Hâret el-Bizâr, and Tarîk Bâb es-Silseleh; Pl. D-G, 5), connects the Jaffa Gate with the Silseleh Gate of the Haram esh-Sherîf (p. 476). On the left, opposite the citadel, is the well-stocked New Bazaar (Pl. D, 5).

At St. John’s Monastery (Pl. 29; E, 5), the Greek pilgrims’ hospice at the S.W. angle of the Mûristân (p. 475), we first turn to the left into the Hâret en-Nâsara (Pl. E, 5, 4; Christians’ Street). On the left is the very ancient Patriarch’s Pool (Birket Hammâm el-Batrak; Pl. E, 5), assigned by tradition to king Hezekiah (about 700 B.C.); on the right is the Patriarch’s Bath. Opposite the Great Greek Monastery (Deir er-Rûm el-Kebîr; Pl. D, E, 4, 5), is, on the right, the entrance to the—

*Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Pl. E, 4; adm., see p. 471), whose principal dome, crowned with a gilded cross, is everywhere conspicuous. This, especially at Easter, is the great goal of the pilgrims. The discovery of the Holy Sepulchre, which Eusebius, Bishop of Cæsarea, the father of church history (314–40), tells us was made by Constantine, induced that emperor to build a round church here, the so-called Anastasis (church of the resurrection), and a five-aisled basilica, dedicated to the sign of the Cross (Martyrion). These churches having been burned down by the Persians (p. 473), Abbot Modestus, under Emp. Heraclius, began to build, in 629, a new church of the resurrection, the prototype of the Dome of the Rock (p. 477), a new church of the Cross, and a small Calvary church on the supposed site of the Crucifixion (Golgotha). A fourth church, that of St. Mary, is said to have existed here in 670. Between 1140 and 1149, the period of the Second Crusade, the Crusaders caused a great new church to be built by the architect Jourdain, in the Romanesque transition style, under Arabian influence, an edifice intended to embrace almost all the holy places. On the E. side of the new double church a chapel was dedicated to St. Helena (d. about 326), the mother of Constantine, who, according to later historians, once made a pilgrimage to the holy places and discovered the true Cross near the Sepulchre. On the S. side of the double church a Gothic clock-tower, originally detached, was erected in 1160–80. After the destructions of 1187 and 1244 (see p. 473), we hear of a handsome new church existing here in 1310. At length in 1719 a great part of the church was rebuilt, and at the joint cost of the Greeks and the Armenians, again in 1810 by the architect Komnenos Kalfa. Since then the Greek cathedral, the dome-roofed ‘Catholicon’, has occupied the nave of what was once the Crusaders’ basilica. Among the many additions the chapel of the Apparition (p. 475) is one of the oldest (14th cent.).

In the N.W. corner of the Quadrangle, or outer court, over the Chapel of the Forty Martyrs, rises the Bell Tower, the upper part of which has been destroyed. The Façade, dating from the era of the Crusades, has fine reliefs of the French school over the portals.

A vestibule, where the custodians (p. 471) sit, leads to the Stone of Unction (John xix. 38–40), last renewed in 1808.

The great Rotunda of the Sepulchre still has the foundation pillars, the massive outer wall of the W. semicircle, and the three apses of the Crusaders’ church. The round central structure embraces the Chapel of the Sepulchre and the Angels’ Chapel. Adjoining the Sepulchre is the 14th station of the Via Dolorosa (see below).

From the N.E. side of the ambulatory an ante-room leads to the Chapel of the Apparition, the chief Latin (Rom. Cath.) sanctuary, on the spot where Christ is said to have appeared to his mother. In a niche is shown a fragment of the ‘Column of Scourging’.

The Nave, which we next visit, has suffered greatly from the introduction of the Catholicon. The pointed windows, the clustered pillars, and the groined vaulting still bear traces of their origin in the Crusaders’ era. The southmost of the three chapels in the apse, in the outer wall of the choir ambulatory, contains the ‘Column of the Derision’.

To the left of this chapel a flight of 29 steps descends to St. Helena’s Chapel, belonging to the Armenians, on the site of Constantine’s basilica, with foundations of the period of Modestus; 13 more steps descend thence to the Chapel of the Finding of the Cross.

We now return to the ambulatory and ascend from it, to the left (S.), to the higher-lying Golgotha Chapels, the 10–13th stations on the Via Dolorosa (see below).

On the S. side of the quadrangle, in front of the Holy Sepulchre Church, lies the Mûristân (Pl. E, F, 5), an open space of 170 by 150 yds., which contained, from the days of Charlemagne onwards, the hostels and hospitals of the European pilgrims and, from 1140, the grand buildings of the Knights of St. John. Saladin (p. 443) granted it as a charitable endowment (wakf) to the Dome of the Rock (p. 477), but allowed the old hostels to remain. The larger W. half, with modern shops, now belongs to the Greek patriarchate; the E. half was presented by the sultan to Prussia. At the N.E. corner, next to the street called Hâret ed-Dabbârîn, is the German Prot. Church of the Redeemer (Pl. E, 5).

The Mûristân is bounded on the E. by the now unimportant Old Bazaar, or sûk, the three parallel streets of which form part of the great thoroughfare between the Damascus and Zion gates (p. 473). The middle street, the Sûk el-Attârin (p. 335), is continued to the N. by the Khân ez-Zeit (Pl. F, 4), from which an alley on the left leads to the Abyssinian and Coptic Monasteries.

At the Coptic Monastery is the 9th station on the Via Dolorosa, the ‘route of suffering’, mentioned for the first time in the 16th cent., on which Christ is said to have borne the Cross from Pilate’s house to Golgotha. The last five stations are within the Holy Sepulchre Church (see above). The other stations lie between the Greek Monastery of St. Caralombos (Pl. 24, E F, 4; 8th station) and the Barracks (Pl. G, 3; 1st station) in the Tarîk Bâb Sitti Maryam (street of the Virgin Mary’s gate).

This street leads to the E. to St. Stephen’s Gate (Pl. H, I, 3; 2405 ft.), the only E. gate of the city, called by the natives Bâb Sitti Maryam, or Lady Mary’s Gate, from its proximity to the Virgin’s Tomb (see p. 480).

Within the gate a passage leads to the N. to the fine old Church of St. Anne (Pl. H, 3; Arabic Es-Salâhiyeh), on the supposed site of the house of Joachim and Anna, the parents of the Virgin. It is mentioned as already existing in the 7th cent., but in its present form dates chiefly from the 12th. The crypt hewn in the rock is the traditional birthplace of the Virgin, and the tombs of Joachim and Anna also are now pointed out.

We now retrace our steps towards the W., and halfway along the Via Dolorosa follow the El-Wâd street (Pl. F, G, 4, 5) to the left, through the hollow of the ancient Tyropœon (p. 472), to the Sûk el-Kattânîn (see below), near the entrance to the Haram esh-Sherîf; or starting from the Old Bazaar, we reach the same point by the Tarîk Bâb es-Silseleh (Pl. F, G, 5).

The *Haram esh-Sherîf (Pl. G-I, 4–6; ‘noble sanctuary’), the ancient site of the Temple, is the most interesting place in Jerusalem. Adm., see p. 471. The usual entrance is by the Bâb el-Kattânîn (Pl. G, 4, 5), the central W. gate, built by En-Nâsir (p. 448) in 1318, behind the now deserted Sûk el-Kattânîn (cotton-market).

On this site king David erected an altar (2 Sam. xxiv. 25), and Solomon built his palace and Temple. Here stood also the second Temple, erected about 520–516 after the Babylonish captivity, and the third Temple, begun by Herod the Great (p. 472) in 20 B.C. but never completed on the grand scale projected. On the same spot Hadrian erected a temple of Jupiter as the chief sanctuary of Ælia Capitolina (p. 472), and near the S. wall of the great quadrangle Justinian built a basilica in honour of the Virgin, which afterwards became the mosque of El-Aksâ. Beyond these facts little or nothing is known of the history of this memorable site during the early centuries of the Christian era.

Mohammed, who claimed to have visited this spot, evinced great reverence for the ancient Temple, and before he had broken off his relations with the Jews he even enjoined believers to turn towards Jerusalem in prayer. About the year 637 caliph Omar converted the church of St. Mary into a mosque, and the Omaiyade Abd el-Melik (685–705) erected the famous Dome of the Rock on a platform in the centre of the sacred precincts, a building which the Crusaders took to be Solomon’s Temple. Adjoining the mosque of El-Aksâ, then called the Porticus or Palatium Salomonis, probably stood the royal palace of the Franks and the castle of the Knights Templar.

The huge substructions of the Temple plateau, the surface of which was much altered by Saladin, still date from the reign of Herod. The plateau itself forms an immense quadrangle of irregular shape (W. side 536, E. side 518, N. side 351, S. side 310 yds. long). In the N.W. corner, once perhaps the site of Baris, the castle of the Maccabees, and of the Roman castle of Antonia, rises the highest Minaret of the Haram. The buildings by the W. and N. walls, Koran schools, dwellings, etc., with open arcades on the groundfloor, are unimportant. The great quadrangle, now partly planted with trees, is studded with numerous mastabas, raised platforms with prayer-niches (mihrâbs), and sebîls, or fountains for the religious ablutions. Especially to the S.W. of the Dome the ground is honeycombed with deep Cisterns, some of which are very ancient.

Entering the precincts and passing the pretty Sebîl of Kâït Bey (p. 458) we mount one of the flights of steps of the time of Abd el-Melik to the Platform, 10 ft. in height.

The so-called **Dome of the Rock (Kubbet es-Sakhra; Pl. H, 4, 5), usually but erroneously called Omar’s Mosque, was built, according to the Arabian historians, by Abd el-Melik for political reasons, the Omaiyades being at that period denied access to the Kaaba at Mecca. The year 72 of the Hegira (691–2) is mentioned as the date of its erection. The chief restorations in the middle ages were undertaken by the Fatimite Ez-Zâhir (1021–36), who rebuilt the dome in 1022, and by Saladin, to whom is due the superb stucco decoration of the dome. Most of the later additions were made by the Turkish sultan Suleiman the Great (1520–66). The W. porch alone is quite modern.

The building, in the late-Roman and Byzantine style (comp. p. 548), is in the form of an octagon, 50 yds. in diameter, with sides 22½ yds. in length, and with two concentric aisles. Above the inner aisle rises the boldly designed *Dome (98 ft. high), consisting of two wooden vaults placed one inside the other and roofed with plates of copper. The external walls are still incrusted below with their old slabs of marble, while above the window-sills the ancient glass mosaics were replaced in the time of Suleiman by superb Persian porcelain-tiles (kishâni). The keel-arches of the windows are of the same period.

The two aisles are separated by two series of supports. Between the eight pillars of the outer octagonal aisle, which are incrusted with marble dating from the time of Suleiman, rise sixteen columns with late-Roman or early-Byzantine capitals, and the round-arched arcades are connected, above the Byzantine imposts, by tie-beams overlaid with copper. The inner row of supports, bearing the dome, consists of four large pillars and twelve antique monolith columns. The pointed arches of the vaulting here, dating from Suleiman’s restoration, rest immediately on the capitals. The wrought-iron screen is of French workmanship of the Crusaders’ era.

The glass *Mosaics in the spandrels of the outer aisle, executed by Byzantine artificers, all belong to the earliest building; those in the drum of the dome are partly of the time of Ez-Zâhir and of Saladin. The stucco decoration of the dome was restored under Mohammed en-Nâsir (p. 448) in 1318, and again in 1830. The *Windows, dating from Suleiman’s restoration, present a marvellous wealth of colouring.

Enclosed by the inner aisle, and best viewed from the high bench beside the N.W. gate of the screen, is the Sacred Rock, measuring 18½ by 14½ yds., and rising 4–6½ ft. above the pavement of the church. Under it is a cavity, probably once a cistern. The rock is supposed to have been the site of the great Jewish altar of burnt-offering. The Jews and the Moslems believe it to have been also the scene of Abraham’s sacrifice. From this spot Mohammed is said to have been translated to heaven on his miraculous steed Burâk, while an angel restrained the rock in its attempt to follow him; here too, they believe, will be erected the throne of God on the Day of Judgment.

Outside the E. gate of the Dome of the Rock, and probably as old, is the so-called Dome of the Chain (Kubbet es-Silseleh, or Mehkemet Dâûd, ‘David’s Place of Judgment’). This structure consists of two concentric rows of columns, the outer forming a hexagon, the inner an endecagon. The large prayer-recess on the S. side, facing Mecca, is of the 13th century. The arcades, connected by tie-beams, and the drum of the dome are richly adorned with fayence tiles of Suleiman’s period. Across the dome, it is said, will be stretched a chain (silseleh) on the Day of Judgment, from which the awful scales will be suspended.

We now descend from the platform by the steps near the ‘Summer Pulpit’ (15th cent.), at the S.E. angle, and walk past the round basin of El-Kâs to the—

*Mesjid el-Aksâ (Pl. H, 5, 6), the sanctuary ‘farthest’ from Mecca and one of the holy places of Proto-Islam, to which God is said to have brought Mohammed from Mecca in one night (Sureh xvii. 1). The mosque without its additions is now 88 yds. long and 60 yds. wide. Of the church of Justinian nothing apparently has survived except the columns of the nave and two inner aisles. The capitals perhaps date from caliph Omar’s period (637). The broad transept was probably constructed by the Abbaside El-Mehdi (775–95); the wooden dome is now covered with lead outside. The transept gave the edifice the form of a ⟙, which was converted later into a rectangle by the two rows of aisles added on the E. and W. These, in their present shape, and the pointed arcades of the nave and inner aisles, connected by tie-beams, belong to a late period of restoration. The so-called White Mosque, now set apart for women, a long double corridor to the W. of the transept, probably once belonged to the castle of the Knights Templar. The latest addition is the porch built by Melik el-Muazzam Isâ (d. 1227) and restored at a later period. Its middle arcades imitate Frank Gothic.

The interior was once almost as sumptuously decorated as the Dome of the Rock. The *Pulpit (mimbar), carved in wood and inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl, executed by order of Nûreddîn (p. 485) in 1169 for the great mosque of Aleppo, was presented by Saladin. To him also the mosque owes the prayer-recess, with its graceful little marble columns, the superb mosaics of the mihrâb-wall, and the drum of the dome. The author or at least restorer of the decorations of the dome is said to have been Mohammed en-Nâsir (p. 448). The windows date only from the time of Suleiman.

In the S.E. corner of the Haram area a staircase descends to a small Moslem Oratory with the ‘Cradle of Christ’ and to 13 vaulted galleries, part of the old substructure of the Haram, known as Solomon’s Stables. In the sixth gallery, counting from the E., there is a small door in the S. wall called the ‘Single Gate‘, an old entrance to the Haram.

The roof of the ‘Golden Gate’ (Pl. H, I, 4; Bâb ed-Dâhirîyeh), the only E. gate of the Haram, dating from the reign of Justinian (?) but now built up, affords a survey of the whole great quadrangle. At our feet lies the Kidron valley (p. 480), with its rock-tombs, and opposite rises the Mt. of Olives (see below).

Time permitting, we may now visit the Wailing Place of the Jews (Kautal Maarbei; Pl. G, 5), to the W. of the Haram, reached by descending (to the S.) the eastmost side-street of the Tarîk Bâb es-Silseleh. It is probable that the Jews, who never enter the Haram precincts for fear of desecrating the holy of holies, were in the habit of repairing hither as early as the middle ages to bewail the downfall of Jerusalem. The scene is most touching on Friday afternoons (after 4 p.m.), when crowds of mourners flock to the place and litanies are chanted.

The Mount of Olives (Mons Oliveti, Jebel et-Tûr), running parallel to the Temple hill, is closely associated with the last days of Christ on earth. It is visited (best in the forenoon) either by carriage from the Jaffa or the Damascus Gate (10–12 fr.; ascent ½ hr.), or on horseback (p. 471) or on foot from St. Stephen’s Gate (p. 475). Those who return by the valley of the Kidron should order their carriage to meet them at the Garden of Gethsemane.

From the Damascus Gate (p. 473) the road leads past the Dominican Monastery of St. Stephen (on the right; Pl. E, 1) and then, beyond the Anglican Bishop’s House, past the so-called Tombs of the Kings (on the right). This large subterranean burial-ground, with its tomb-chambers and shaft-tombs, probably belonged to queen Helena of Adiabene and her family (1st cent. A.D.). The road to Nâbulus soon diverges to the left; ours ascends in a wide curve northwards to the top of the Scopus and to the Mt. of Olives.

On the N. height of the Mt. of Olives, to the left of the road, is the new German Augusta Victoria Institute (sanatorium and church).

On the E. summit (2665 ft.) are the Russian Buildings, a pilgrims’ hospice, the Russian Church of the Ascension, and a six-storied Belvedere Tower (214 steps). The *Panorama embraces the city and the hills around Jerusalem and Bethlehem (the latter itself not visible). Towards the E. lie the Dead Sea (1293 ft. below sea-level) and the Jordan valley (Arabic El-Ghôr), and among the bluish Mts. of Moab rises Mt. Nebo (2644 ft.), whence Moses beheld the promised land before his death (Deut. xxxiv. 1–4).

A little to the W. of the Russian Buildings lies the poor village Kafr et-Tûr. Near it is the Chapel of the Ascension, built in 1834–5, to mark the scene of the Ascension (in contradiction to Luke xxiv. 50, ‘He led them out as far as Bethany’). Of the earlier churches here, one a round building of Emp. Constantine, the other built by the Crusaders, few traces are left.

To the S. of the village are the Latin Buildings, including the Credo and Paternoster Churches (1898).

A steep path descends hence, to the W., to the Garden of Gethsemane (Pl. K, 4), now the property of the Franciscans. Near the entrance (E. side) a rock marks the spot where Peter, James, and John are said to have slept (Mark xiv. 32 et seq.), and the fragment of a column close by indicates the traditional scene of the Betrayal. (A monk acts as guide; fee 3–6 pias.) A little higher up the Greeks have their own Garden of Gethsemane, containing the many-domed Church of Mary Magdalen (Pl. K, 4).

A few paces to the N.W., on the road to the upper bridge over the Kidron (Pl. I, 3) and to St. Stephen’s Gate, rises St. Mary’s Church (Pl. K, 3; Arabic Kenîset Sitti Maryam), built by queen Milicent or Melisendis (d. 1161) on the site of an ancient church mentioned as early as the 5th cent.; it contains the ‘coffin of the Virgin’, in which she lay until her Assumption.

The Valley of the Kidron, identified from a very early age with the Valley of Jehoshaphat, has been supposed, ever since pre-Christian times, owing to a misinterpretation of Joel iii. 2, to be the future scene of the Last Judgment. The Moslems bury their dead on the E. slope of the Haram esh-Sherîf, and the Jews on the W. slope of the Mt. of Olives.

From the Jericho road, to the S. of the Garden of Gethsemane, a path diverges to the right to the lower bridge over the Kidron (Pl. I, 5). To the left of the path are the so-called Tomb of Absalom, a cube of rock, with a curious conical roof expanding at the top; St. James’s Cavern, a rock-tomb; and the Pyramid of Zacharias. All these date from the Græco-Roman period.

Farther on, to the S.E., passing below the hill-village of Siloah (Pl. H, I, 7–9; Arabic Kafr Silwân), we come to St. Mary’s Fountain (Pl. H, 7; Aïn Sitti Maryam), an intermittent spring, probably the Gihon of the Old Testament. Since the time of Hezekiah (about 700 B.C.) its water has flowed through the underground Siloah Conduit to the Pool of Siloam (Pl. G, H, 9), within the Jewish town-wall.

Farther down the valley we reach in a few minutes ‘Job’s Well’ (about 2035 ft.; Bîr Eiyûb).

We return thence to the town by the Valley of Hinnom (p. 472). The ‘Zion Suburb’ (p. 473) rises steeply on the N.W.; to the left is the slope of Jebel Abû Tôr, covered with rock-tombs. Near (12 min.) the Sultan’s Pond (see below) we join the Bethlehem road.

The Excursion to Bethlehem, by a good road (half-a-day; carr. about 12 fr.; horse, see p. 471), will even repay walkers.

The road descends to the S. from the Jaffa Gate (p. 473) into the Valley of Hinnom (see above). Beyond the Birket es-Sultân (Pl. C, D, 8), an old Jewish reservoir restored by Suleiman the Great (16th cent.), the station-road diverges to the right.

Our road leads to the S.W. across the tableland of El-Bukeia (p. 470), past the traditional Well of the Magi (Matth. ii. 9), to the (3 M.) Greek convent of Mâr Elyâs (left). Bethlehem appears in the foreground. Fine view of the Dead Sea (p. 479) to the left.

At (4 M.) ‘Rachel’s Tomb’ (Kubbet Râhîl), built like the welis or tombs of Moslem saints, the Hebron road diverges to the right.