5 M. Bethlehem (2550 ft.; pop. about 11,000, almost all Christians), the home of David and the birthplace of our Saviour, has a situation resembling that of Jerusalem. It consists of eight different quarters, containing many monasteries, hospitals, and schools. Fine view from the German Prot. Weihnachtskirche (‘Christmas Church’, 1893), on the W. outskirts.

Over the traditional birthplace of Christ rises *St. Mary’s Church, now occupied by the Greeks, Latins, and Armenians jointly. The original columnar basilica of the time of Constantine, with its double aisles, is still the nucleus of the present church. It was thoroughly renovated by the Crusaders, and the superb wallmosaics were restored by the Byzantine Emp. Manuel Comnenos (1143–80). The Greeks, who were in sole possession from 1672 to 1852, unfortunately added the transept wall.

Interior. The entrance is by the old central portal, approached from an open space once occupied by an atrium. Three passages lead through the transept, with semicircular apses at either end, to the semicircular choir. Among the almost obliterated mosaics is a quaint representation of the Entry into Jerusalem in the S. apse.

Adjoining the choir are two flights of steps descending into the Crypt, or Chapel of the Nativity, and to the ‘Chapel of the Manger’, the ‘dwelling of St. Jerome’ (b. about 340 in Dalmatia, d. in 420 at Bethlehem), and his tomb, which also are highly revered.

The stairs on the N. side ascend to the Latin Church of St. Catharine, through which we return to the principal church.

For full details, see Baedeker’s Palestine and Syria.

74. Beirut. Excursion to Damascus.

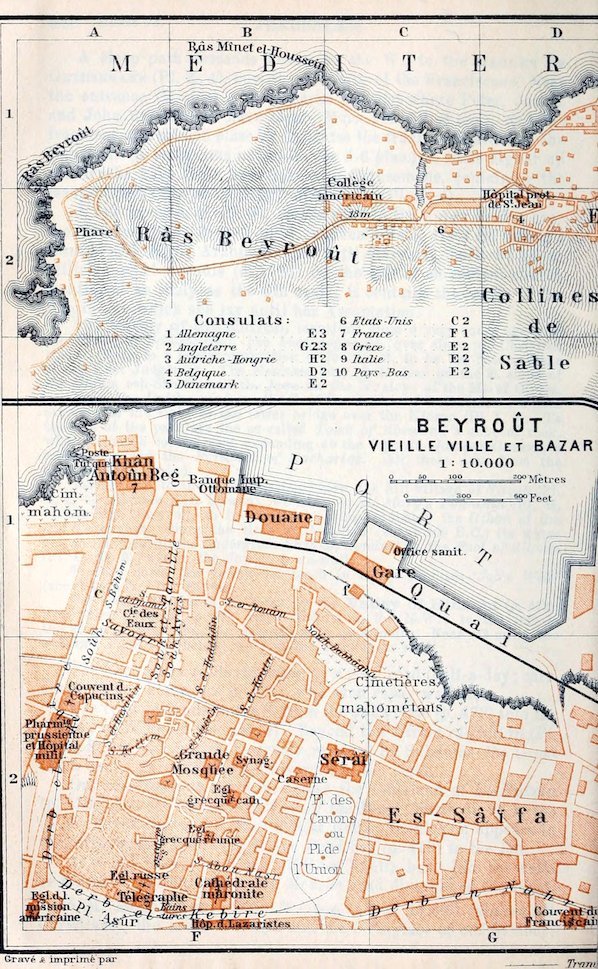

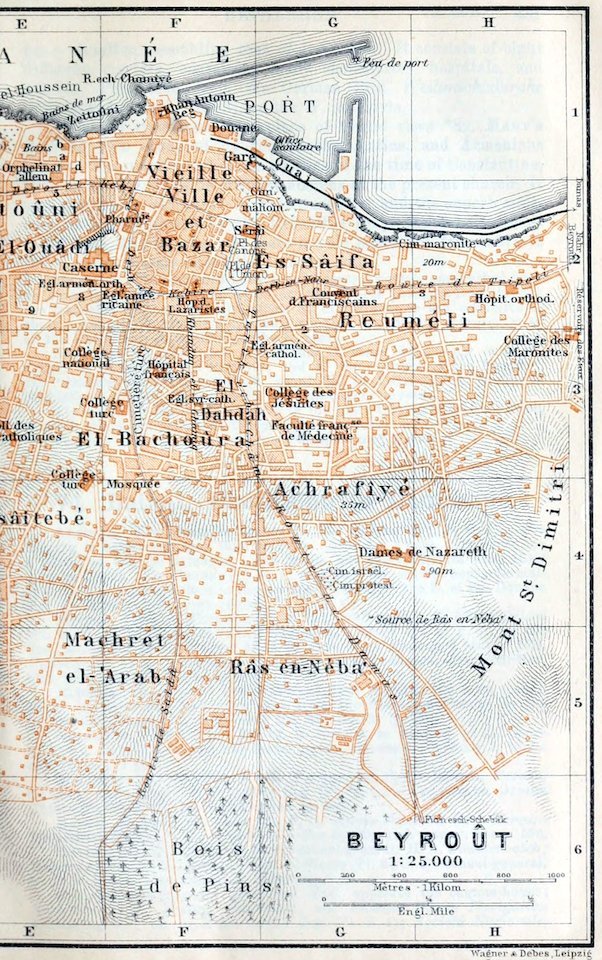

Arrival. The steamers anchor in the harbour (Pl. F, G, 1). The landing is better managed than at Jaffa. Boat for 1 pers. 2 fr.; less for a party, as may be arranged. The hotels and tourist-agents send their men on board. The Douane (Pl. F, 1; passport and custom-house formalities; comp. p. 537) is close to the landing-place.—To the E. of the Douane lies the Railway Station (Gare; Pl. F, G, 1).

Hotels. *Hôt. d’Allemagne (Pl. a; E, 1), well spoken of, Hôt. d’Orient (Pl. b; E, 1), both near the sea; Gassmann’s Hotel (Pl. c; F, 1), in the Sûk ed-Jemîl; pens. at these 12–15 fr. (less for a prolonged stay); Hôt. Victoria (Pl. d; E, 1), plainer, etc.—Restaurants. Blaich, Jean Schröter, both near the Hôt. d’Allemagne.

Electric Tramways. Four different lines traverse the town (comp. Plan); of these the Blue Line runs from the Place des Canons to the Lighthouse (Phare; Pl. A, 2), near the Râs Beirût (p. 483).

Carriages. Drive 1 fr.; per hr. in town 2, in country 2–3 fr. (more on Sun.). Longer drives as may be arranged.—Horses. Half-day 1, whole day 1½ mejidieh.

Post Offices. Turkish (Poste Turque; Pl. F, 1); British, French, German, and others, Khân Antûn Beg (Pl. F, 1).—Telegraph Office (Internat.; Pl. F, 2), Derb el-Kebîreh (p. 483).

Banks. Banque Ottomane (Pl. F, 1), Anglo-Palestine Co., German Palaestina-Bank, all at the harbour.—For the Turkish money, see p. 536.

Consulates. British (Pl. 2; G, 2): consul-general, H. A. Cumberbatch; vice-consul, H. E. W. Young.—United States (Pl. 6; C, 2): consul-general, G. B. Ravndal; vice-consul, L. Memminger.

Steamboat Agencies. Khedivial Mail, opposite the custom-house; Austrian Lloyd, Messag. Maritimes, and Russian Steam Navigation & Trading Co., all in Khân Antûn Beg (Pl. F, 1); Società Nazionale, opposite the German Bank.—Tourist Agents. Thos. Cook & Son, in the Hôtel d’Orient; Agence Lubin, Khân Antûn Beg (Pl. F, 1).

Churches. American Presbyterian Mission (Pl. F, 2); services on Sun. at 11 a.m. in English and at 9 a.m. in Arabic. Among the many other missions and schools are the British Syrian, the Ch. of Scotland Jewish, the Syrian Prot., and a number of German, French, etc.

Beirut (Fr. Beyrout, Arab. Beirût; pop. 190,000), the chief commercial place in Syria (Esh-Shâm), and the capital of the Turkish vilayet (province of a vali or governor) of that name, is beautifully situated, in 33° 50′ N. lat. and 35° 30′ E. long., on the S. shore of St. George’s Bay, between Râs Beirût (p. 483) and Mt. St. Dimitri. To the E. rises Lebanon (p. xxxiv), with Jebel Keneiseh and Jebel Sannîn (p. 483). The climate is mild and pleasant (mean temperature of Jan. 56° Fahr., of Aug. 81°), and the rainfall is considerable (34 in.). The sea-breezes render the summer bearable, but they are apt to fail in August and September. Many of the citizens then seek refuge in the summer quarters of Lebanon, to which Egyptians and Cypriotes also resort.

Berytus (‘fountain’) is mentioned in the tablets of Tell el-Amarna (p. 456) as the seat of the Egyptian vassal Ammunira. It lay in the territory of the Giblites, a northern branch of the Phœnicians. In 140 B.C., during the wars of the Diadochi, the town was entirely destroyed. The Romans rebuilt it and named it Colonia Julia Augusta Felix Berytus, after the daughter of Emp. Augustus. In the 3rd cent. its school of Roman law became renowned. From that time down to the present day it has been noted also for its silk-industry, which was transplanted to Greece and to Sicily. In 529 the prosperity of the town was destroyed by an earthquake. Since its conquest by the Arabs in 635 it has been in the possession of the Moslems, except during the brief Crusaders’ occupation. Like Saida (p. 469) it was a favourite residence of the able Druse prince Fakhreddîn (1595–1634), who in league with the Venetians wrested Central Syria from the Turks. They, however, later recaptured Beirut. During the 19th cent. Beirut gradually attained a new lease of prosperity. Under the Egyptian rule its sea-borne commerce increased, while Saida and Tripoli declined. In 1840 the town was bombarded by the British fleet and recaptured for the Turks. After the massacre of Christians in 1860 (see p. 485) many Christians from central Syria settled at Beirut.

The Moslem inhabitants (about 65,000) are in a considerable minority. Among the Christians there are 64,000 Greeks, 40,000 Maronites, and 2100 Protestants. The Jews number about 5500. An unusually large percentage of the natives can read and write. The chief language is Arabic.

Beirut offers few sights. The poor and closely built Old Town contains the Great Mosque (Pl. F, 2), once a Crusader’s church, the Greek Churches, and the Maronite Cathedral (Pl. F, 2).

The Sûks or markets have lost much of their Oriental character. Most of the genuine native products come from Lebanon (keffîyehs or head-cloths, embroidery, woven stuffs, slippers, bridal chests, etc.). The filigree-work has long been noted (sold by weight).

The native population may be studied also in the large Place des Canons or Place de l’Union (Pl. F, 2), on the S. side of the Serâi or government-buildings. The numerous Arabian cafés are for men only.

The broad streets of the New Town skirt the picturesque hill-sides. Palm, orange, and lemon trees abound in the beautiful gardens. The Damascus Road (tramway; Pl. G, 4, 5) leads to the S. in ½ hr. to the Bois de Pins (Pl. G, F, 6), a pine-wood planted by Fakhreddîn for protection against the sand of the dunes.

The finest point of view is *Mt. St. Dimitri (Pl. H, 3–5; best by evening light), ½ hr. to the S.E. of the old town. From the Place des Canons we follow the Derb en-Nahr (Pl. G, 2) and the Tripoli road, turn to the right beyond the Greek Orthodox Hospital (Pl. H, 2), and then ascend to the left.

From the Place des Canons (tramway, see p. 481) the Derb el-Kebîreh (Pl. F, E, 2) and Derb el-Prusiani lead to the W., below the dunes, to the Râs Beirût. After ½ hr. we reach the Lighthouse (Phare or Fanâr; Pl. A, 2). Thence the road descends in windings to the sea and farther on to the ‘Pigeons’ Grottoes’ (reached by boat from the harbour in ½ hr.; 1½ mej.). The light is best near sunset.

From Beirut to Damascus, 91½ M., narrow-gauge railway (20 M. being on Abt’s rack-and-pinion system). Two trains daily in 9¼–11 hrs. (fare 110 pias. 10 or 75 pias.). The passenger should have the exact fare ready before booking. Reyâk is the diningstation for the day-train.

This Railway Company (French) has its own rate of exchange: 1 napoleon = 87 pias.; 1 sovereign = 110 pias.; 1 mejidieh = 18½ pias.

The train runs from the harbour to the E., close to the sea, to the (1½ M.) Chief Station, and through the valley of the Nahr Beirût at the E. base of Mt. St. Dimitri, soon turning to the S. to (4½ M.) El-Hadet. It then rapidly ascends the slopes of Lebanon.

10½ M. Areiya, 13 M. Aleih (2460 ft.), two summer resorts in the Lebanon. The train threads a tunnel to the highest point of the line (4879 ft.). We then descend, enjoying fine views, to the right and left, of Jebel el-Barûk (6749 ft.) and Jebel Keneiseh (6660 ft.), to (35 M.) El-Muallaka, a large village, and station for the Christian town of Zahleh (3101 ft.) on the S. spurs of Jebel Sannîn (8556 ft.; snow-capped in early summer).

We next traverse the lofty valley of El-Bikâ, the ancient Bucca Vallis, watered by the Nahr el-Lîtânî (Leontes), once the most fertile part of Coelesyria (‘hollow Syria’).

41 M. Reyâk or Rayak (Buffet; halt of ½ hr.), junction for Baalbek (Heliopolis) and Aleppo (Haleb).

Passing through the narrow Wâdi Yahfûfeh we next ascend the Anti-Lebanon Mts.; 54½ M. Sarrâyâ or Zerghaya (4610 ft.) lies between their two main ranges, on the watershed between the Bikâ and the plain of Damascus.

Beyond (61 M.) Ez-Zebedâni (3888 ft.) the train enters the valley of that name, famed for its fruit and watered by the Nahr Baradâ (Gr. Chrysorrhoas, ‘gold stream’). 71½ M. Sûk Wâdi Baradâ (‘market of Baradâ vale’), at the end of a defile.

76½ M. Aïn Fîjeh, the chief source of the Baradâ, has remains of a Roman Nymphæum (see p. 241). 85 M. Dummar, a villa-suburb of Damascus. The city with its minarets soon comes in sight.

The floor of the Baradâ valley, between (left and right) Jebel Kâsyûn (p. 489) and the hills of Kalabât el-Mezzeh, is well planted with trees. At the mouth of the valley the river divides into seven branches which water the great plain of Damascus.

Skirting large meadows (merj), then orchards, and a Roman Aqueduct, the train reaches (89½ M.) Damascus-Beramkeh (see below), where it is usual to alight, and lastly runs past the W. side of El-Meidân (p. 487) to (91½ M.) Damascus-Meidân.

Damascus.—Railway Stations. 1. Beramkeh or Baramki, near the hotels and the Serâi.—2. Meidân, near the Bauwâbet Allah, chief station of the Beirut line.—3. Kadem, for the Hejâz line (p. 469; no cabs).—Cabs and tramway, see below.

Hotels. Hôt. Victoria, Hôt. d’Orient, Palace Hotel, all near the Beramkeh Station and the Serâi; Hôt. d’Angleterre, to the E. of the Serâi Square; pens. 10–15 fr. (or more when crowded), in the quiet season 6–10 fr.; good wine of the country (from Shtôra) 1½–5 fr.

Arabian Cafés, the largest and most interesting in the East, mostly on an arm of the Baradâ, in the Serâi Square, on the Beirut road, the Aleppo road, etc.—Visitors should beware of the cold night-air from the river after a hot day.

Cabs in the Serâi Square, 6–7 pias, per drive, or 10–12 pias. per hr. (always to be agreed upon beforehand); but more on holidays and in the height of the season.—Electric Tramway (3¼ M.) from the El-Meidân quarter viâ the Serâi Square to the suburb of Es-Sâlehîyeh (p. 489).

Post Office and International Telegraph Office, Serâi Square.

Consuls. British, G. P. Devey, near the Beramkeh Station.—United States Consular Agent, N. Meshâka, in the Christian quarter.

Dragomans (Arabic terjumân), about 10 fr. a day during the season, desirable for new-comers (comp. p. xxvi), and essential in visiting the Omaiyade Mosque. Travellers should beware of trusting them with money or purchases.

Banks. Banque Ottomane, German Palaestina-Bank, both in the Sûk el-Asrunîyeh (p. 486).—Photographs sold by Suleimân Hakîm, at the E. end of the Straight Street (p. 487).—Baths. The Hammâm el-Khaiyâtin and the Hammâm ed-Derwîshîyeh or el-Malikeh, among others, are worth seeing.

Churches. English Church (St. John’s), of the London Jews Society, in the Hammâm el-Kari Quarter; Rev. J. E. Hanauer; Sun. service at 10.30. Also Edinburgh Medical, British Syrian Mission, Irish Presbyterian, and other missions, with excellent schools, hospitals, etc.—The Latins, the Greeks, and the Jews also have their own schools.

Sights (when time is limited). 1st Day, in the forenoon, Serâi Square, the Bazaars, and Meidân (pp. 486, 487); afternoon, Es-Sâlehîyeh and Jebel Kâsyûn (p. 489).—2nd Day. Mosque of the Omaiyades (p. 488).

Damascus (2268 ft.), formerly called Dimishk, a name still sometimes used, but commonly called by the natives Esh-Shâm (a term applied also to the whole of Syria; p. 482), lies on the borders of the Syrian Desert (p. xxxiii) in the Rûta, a beautiful oasis between Anti-Lebanon and the ‘Meadow Lakes‘, into which fall all the branches and canals of the Baradâ. As the Koran pictures paradise as a garden, where luscious fruits drop into the mouth, the Arabs have ever regarded Damascus, with its luxuriant orchards, as the prototype of that blissful abode. The Rûta does not, however, and least of all in winter, impress Europeans quite so favourably. Yet in May, when the walnut-tree is in full leaf and the vine climbs exuberantly from tree to tree, or still later, when the apricot-trees in the midst of their rich carpet of green herbage bear their countless golden fruits and the pomegranates are in the perfection of their blossom, the gardens are truly beautiful.

History. With regard to the foundation of Damascus, which like the whole of Syria belonged from about 1500 B. C. onwards to Egypt and to the Hittite empire (p. 547) alternately, countless traditions are current among the Jews, Christians, and Mohammedans. After David had temporarily extended his sway to Damascus, there arose here, in Solomon’s time, an independent Aramæan kingdom under Rezon (1 Kings, xi. 23–25). In the protracted struggles between the neighbouring kingdoms of Israel and Judah the Syrian kings generally succeeded, by means of judicious alliances, in maintaining their independence. In the annals of the Assyrians, who destroyed Damascus in 732, the town is called Dimaski and the kingdom Imîrisu. From that time onwards Damascus lost its political importance; but it continued, especially under the sway of the Seleucides of Antioch during the period of the Diadochi, to prosper as a trading and industrial city and as the starting-point of the caravan traffic with Mesopotamia and Persia. When it became a Roman provincial city it formed a political bulwark against the Arabs (Nabatæans) and Parthians. In 611 A. D., under the Byzantine emperor Heraclius, many of its inhabitants were carried into captivity by the Sassanide Chosroes II.

With its conquest by the Arabs in 635 begins the most brilliant period in the history of the city. Under Mûawiya (661–79), founder of the dynasty of the Omaiyades, the greatest of Arabian princes, it became the seat of the caliphate. But when the Abbasides removed their residence to Mesopotamia in 750 Damascus again sank to the position of a provincial town. It fell successively into the hands of the Egyptian Tulunides and Fatimites (p. 443), and at length in 1075 succumbed to the Seljuks (p. 542). In 1148 it was unsuccessfully besieged by Conrad III. Under Nûreddîn and Saladin (p. 443) Damascus was the chief base of all the wars against the Crusaders. During the conflicts between the Mongols, who under Hûlagû had captured the city in 1260, and the Egyptian Mameluke sultans, Damascus was specially favoured by Beybars (1260–77). During the great predatory expedition of the Mongols under Timur (1399–1400) many scholars and artists, including the city’s famous armourers, were exiled to Samarkand. In 1516 the Turkish sultan Selim I. (p. 542) entered the city as its final conqueror. In 1860 there took place a great massacre of Christians in which the Christian quarter was utterly destroyed and about 6000 Christians killed.

Damascus consists of several different quarters. The Jews’ Quarter, as in the time of the Apostles, adjoins the ‘Straight Street’ (p. 487), on the S.E. side of the city; to the N.E. of it is the poor Christian Quarter. The other parts of the town are Moslem. Far towards the S. stretches the suburb of Meidân, inhabited by peasants. The Arabian houses in the old town are noted for their splendour. They usually contain a spacious court, adorned with fountains, flower-beds, orange-trees, etc., and flanked on the S. side by a lofty open arcade (lîwân) with pointed arches.

The population is roughly estimated at 300,000, of whom four-fifths are Moslems, and there is a garrison of 12,000 men. The Damascenes are notorious for their ignorance and fanaticism. The city was once a great centre of learning, but of about a hundred old medresehs or colleges five only now remain. The famous old weaving industry of the place (still employing about 10,000 primitive looms for silk, woollen, and cotton stuffs) is being steadily ousted by European competition. The busy bazaar traffic here is hardly less picturesque than at Cairo.

We begin our visit at the Serâi Square, the centre of business, built over the main branch of the Baradâ (p. 484). A Monument here commemorates the opening of telegraphic communication with Mecca.

To the E. of the square are the *Bazaars. Through the covered Sûk Ali Pasha (fruit and tobacco) we reach the Sûk el-Hamîr (donkey-market), beyond which is an open street where corn is sold.

At a large plane-tree here we turn to the right to visit the interesting Sûk es-Surûjîyeh (saddlers’ market), which ends near the citadel at the Sûk en-Nahhâsîn. This is the bazaar of the coppersmiths, who make the handsome kursi, or trays placed on wooden stands (p. 487) to serve as tables.

The Citadel (no admittance), a huge castle in the style introduced by the Crusaders, was built in 1219 and was afterwards restored by Beybars (p. 485). The thick walls stand on ancient substructures of massive blocks. At the corners rise square towers with bartisans. The chief gate is on the W. side.

From the W. side of the Citadel the chief thoroughfare of the city (tramway, see p. 484) leads past the Military Serâi and the Hammâm el-Malikeh (or ed-Derwîshîyeh) to the Meidân suburb (p. 487). On the left is the Sûk el-Kharrâtin, or Turners’ Market.

Opposite the Military Serâi is the entrance to the ‘Greek Bazaar‘, a covered market restored in 1893, one of the largest in the city. Among the wares, for which buyers can hardly offer too little, are weapons, antiquities, clothing, pipe-stems, and ‘damascened’ daggers (made in Germany).

Straight through the Greek Bazaar we come to the Sûk elHamîdîyeh, also renovated, with its attractive Arabian sweetmeatshops. A side-street leads thence (l.) to the bazaar for Water Pipes (a kind of hookah smoked by the peasants) and the Sûk el-Asrunîyeh, for utensils, glass, henna (p. 108), and attar of roses (p. 335).

Beyond the Sûk Bâb el-Berîd (on the left) we pass the almost deserted bazaar-street of the Booksellers (leading to the Omaiyade mosque, p. 488), with an old Triumphal Arch; whence a double row of columns once led to the ancient temple (see p. 488). We then turn out of the Hamîdîyeh, to the right, into the Cloth Bazaar (chiefly imported goods). On the right is the Tomb of Nûreddîn (p. 485; unbelievers not admitted).

Adjoining the S. side of the mosque are the bazaar of the Joiners, where we note the kabkâbs, a kind of patten, the kursistands, and the bridal chests, and that of the Goldsmiths.

To the S. of the great mosque is the region of the Khâns (p. 445). We come first to the Khân el-Harîr, or silk-bazaar, now that of the furriers. Near it is the House of Asad Pasha, one of the finest in the city (admittance with the aid of a dragoman). The *Khân Asad Pasha, with its superb stalactite portal, is the largest of all.

Near this point runs the ancient ‘Straight Street’ (Acts ix. 11; now Sûk et-Tawîleh, or ‘long market’), connecting the Meidân road with the Bâb esh-Sherki (see below). A few paces to the W., towards the Meidân road, on the left, is the Khân Suleimân Pasha, for Persian carpets and silks. On the right, where the cloth-bazaar (see above) diverges, is the Silk Bazaar proper, for the sale of keffîyehs (head-cloths, ‘kerchiefs’), table-covers, embroidery, woollen cloaks (abâyehs) for peasants and Bedouins, etc.—We next come to the Sûk el-Attârîn, or spice-market, and to the Meidân Road.

At the point where we join this road rises the Jâmi es-Sinânîyeh, one of the most sumptuous mosques in Damascus. The chief portal (E. side), with its rich stalactites, and the minaret enriched with fayencetiles (kishâni, p. 477) are interesting.

The road forks farther on. We follow the Meidân Road (at first called Sûk es-Sinânîyeh) to the S. Close to the Jâmi el-Idein, where the Meidân Road trends somewhat to the right, we pass, on the left, the Moslem cemetery Makbaret Bâb es-Sarîr, where women weep at the tombs on Thursdays.

The poor suburb of Meidân is modern. Its numerous mosques, including the fine Kâat el-Ûla, are in a ruinous state. The sûk is frequented by corn-dealers, whose grain is heaped up in open barns, and by smiths. The arrival of caravans here presents a picturesque scene. The long strings of camels are attended by ragged Bedouins. Among them are seen Haurânians, bringing their corn to market, and here and there a Kurd shepherd with his square felt-mantle driving his sheep to the shambles. The Bedouins, armed with guns or with long lances, sometimes ride beautiful horses. The wealthy Druses from Lebanon have a most imposing appearance. Twice a year almost all these types may be seen together: on the departure, and again, better still, on the return of the Mecca pilgrims.

If time permit we may now retrace our steps to the cemetery Makbâret Bâb es-Sarîr (see above) whence we take a short walk along the City Wall, on the S.E. side of the old town, beyond the Jewish and Christian quarters (p. 485). Its foundations are Roman, the central part dates from the days of Nûreddîn and the Egyptian sultan El-Ashraf Khalîl (1291), and the upper part from the Turkish period. Passing the camping-ground of the caravans from Bagdad and the Bâb esh-Sherki (E. Gate, originally Roman), we come to the well-preserved Bâb Tûmâ (St. Thomas’s Gate). [About ¾ M. to the S. of the Bâb esh-Sherki are Christian burial-grounds; in one of which Henry Thomas Buckle, the eminent English historian (d. 1862), is interred.]

Near the Bâb Tûmâ on the Aleppo road, beyond the Baradâ, are public gardens and pleasant cafés patronized by Christians. We return thence to the Citadel (p. 486), passing between the Baradâ and the N. side of the town-wall, here probably Byzantine.

The great *Omaiyade Mosque (Jâmi el-Umawî), the finest monument of that dynasty in Syria next to the Dome of the Rock (p. 477), deserves close inspection. Entrance by the W. gate (Bâb el-Berîd), at the end of the booksellers’ sûk (p. 486). Gratuity to the sheikh who acts as guide ca. 1 mejidieh each person; addit. charge for slippers 1–2 pias. each person.

On the site of the mosque there once stood a Roman temple within a large quadrangle. This was succeeded by the church of St. John, a three-aisled basilica built by Emp. Theodosius I. (379–95), and so named from the ‘head of John the Baptist’ (Arabic Yahyâ) preserved in the Confessio, by which the Damascenes still swear. After the conquest of the city by the Arabs (p. 485) the E. half of the church was assigned to the Moslems. Caliph Welîd (705–15) deprived the Christians of the W. half also; and in 708, with the help, it is said, of 1200 Byzantine artificers, he transformed the church into the present mosque, which was so magnificent that Arabian authors extolled it as one of the wonders of the world. Adjacent to it the earliest school of learning was built by caliph Omar II. (717–20). The mosque was carefully restored after fires in 1069, 1400, and 1893, but its ancient glory has departed for ever.

We enter the great Court, which with the mosque itself forms an immense rectangle of 143 by 104 yds., and is flanked by two-storied arcades in the Byzantine style. Behind these are the sleeping-apartments and studies of the teachers and students. The old marble pavement of the court, the mosaic incrustation of the walls, and the crown of pinnacles have disappeared. The fountain of ablution (Kubbet en-Naufara) and the two smaller domed buildings are modern.

Of the three Towers the ‘bride’s minaret’ (Mâdinet el-Arûs; now being rebuilt) on the N. side of the court is said to date from the time of Welîd. The ‘minaret of Jesus’ (Mâdinet Isâ), at the S.E. angle of the mosque, recalls the Crusaders’ edifices. The Mâdinet el-Rarbîyeh, at the S.W. angle, in the Egypto-Arabian style and famed for its view, was added by Kâït Bey (p. 458).

The Interior (143 by 41 yds.), with its three span-roofs, still has the form of an early-Christian basilica. Above each of the two rows of columns, 23 ft. high, which separate the aisles, rises a row of ‘colonnettes’ with round-arch openings, to which similar round-arched windows in the outer walls correspond. In the centre a threefold transept, with four huge pillars supporting the dome (Kubbet en-Nisr, eagle’s dome), indicates the direction of Mecca. The Byzantine glass-mosaics of the time of Welîd, the superb timber ceiling, and the mihrâb and mimbar (15th cent.) were all sadly damaged by the fire of 1893. In the central aisle on the E., over the ‘head of John the Baptist’, rises a modern dome in wood.

On the N. side of the mosque, near the Bâb el-Amâra, are the handsome Tomb of Saladin (Kabr Salâheddîn; adm. 6 pias.) and the Medreseh and Tomb Mosque of Sultan Beybars (p. 485), the latter, according to the inscription, built by his son in 1279.

The suburb of Es-Sâlehîyeh (tramway, see p. 484), l–1/4 M. to the N.W. of the Serâi Square, has about 25,000 inhab., mostly descended from Seljuks, reinforced later by Kurds and by Moslem refugees from Crete. The finest of the ruinous mosques, but not readily shown, is the tomb-mosque of Muhieddîn ibn el-Arâbi (d. 1240), adjoined by the tomb of Abd el-Kâder (p. 221).

From the Cretan quarter at the W. end of the suburb we may ascend, past a platform affording a good view, to the (1¼ hr.) top of the Jebel Kâsyûn (3718 ft.). The *View at the small Kubbet en-Nasr (‘dome of victory’) embraces the city, encircled by the broad green belt of the oasis of the Rûta, the barren heights of Anti-Lebanon, with the long chain of Mt. Hermon (9052 ft.; generally snow-capped) to the S.W.; and to the S.E., beyond Jebel Mâni, the distant hill-country of the Haurân.

Fuller details in Baedeker’s Palestine and Syria.

75. From Beirut to Smyrna (and Constantinople).

713 M. Steamers (agents at Beirut, see p. 481; at Smyrna, p. 531; at Constantinople, pp. 538, 539). 1. Messageries Maritimes (N. Mediterranean Marseilles and Beirut line), from Beirut every alternate Sat. (from Constantinople on Thurs.) viâ Rhodes, Vathy, and Smyrna to Constantinople in 4 days (fare 205 or 140 fr.).—2. Russian Steam Navigation & Trading Co. (see also R. 72; Syria-Egypt circular line, coming from Alexandria) from Beirut on Thurs. night (in the reverse direction Thurs. aft.) viâ Tripoli, Alexandretta, Mersina, Chios, and Smyrna to Constantinople in 8½ days (fare 284 or 212 fr.; to Smyrna 198 or 148 fr.).—3. Khedivial Mail Steamship Co. (comp. also R. 72; from Alexandria and calling at Port Said) leaves Beirut every alternate Wed. foren. (returning Sat. aft.) for Constantinople (in 7 days) viâ Tripoli, Alexandretta, Mersina, Rhodes, Chios, Smyrna, Mytilini, the Dardanelles, and Gallipoli (fare £E 9¼ or £E 6½; see p. 431).

Beirut, see p. 481. The French steamers make straight out to sea in a W. direction. Astern Lebanon remains long in sight.

About half-a-day’s steaming brings us in view of the mountains of Cyprus (Turk. Kibris; pop. ca. 243,000), culminating in the bare Troodos (6408 ft.). Under the Phœnicians and Greeks Kypros, the third-largest island in the Mediterranean (3613 sq. M.), was the seat of the cult of Aphrodite and the scene of a peculiar civilization, the product of Egyptian, Phœnician, and Greek influences in succession. In the middle ages the island was governed by kings of the house of Lusignan and was for a time the seat of the Knights of St. John (1292–1308; see pp. 475, 469, 490). Since 1878 it has been under British protectorate and only nominally Turkish.

Far away to the right we see the table-shaped Capo Greco and the bays of Larnaka and Limassol. We then pass, on the S. coast of Cyprus, the prominent peninsula of Akrotiri, with Cape Gata (lighthouse) and Cape Zevgari. Beyond Port Paphos (lighthouse) we skirt the rocky W. coast of the island.

On the coast of Asia Minor (Anatolia), on a clear day, we sight the beautiful ranges of the Lycian Taurus (10,500 ft.; p. xxxiii); at night the lighthouse on the island of Kasteloryzo (ancient Megiste), with the seaport of Mandraki, is sometimes visible.

To the S.E. of Rhodes we cross one of the deepest parts of the Mediterranean (12,683 ft.).

Nearing Rhodes (562 sq. M.; ca. 30,000 inhab.), the eastmost island of the Greek Archipelago, we sight its S.E. coast as far as Attáiros (4068 ft.; formerly Atabyrion) and Cape Lartos. The latter rises beyond the small bay of Lindos, which together with Ialysos and Kamiros, ancient Greek towns on the N. coast, and with Cnidus, Cos, and Halicarnassus, once formed the league of the Doric Hexapolis.

The French steamers call at Rhodes (Hôt. Karayannis, good; Brit. vice-cons.), the capital of the island, picturesquely situated at its N.E. point. Founded in 408 B. C. by the three older towns (see above) it became famous in later Greek times for its navy and for the Colossus of Rhodes, a bronze statue of Helios 112 ft. high, which was accounted one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The ruinous mediæval *Fortifications and the Strada dei Cavalieri, with the old ‘Houses’ (places of assembly) of the different nations, recall the mediæval glory of Rhodes under the sway of the Knights of St. John (1308–1522) after their expulsion from Cyprus (p. 489).

We next steer through the Ægean Sea, where the scenery and the historic associations are alike most attractive. We pass the S. Sporades, Greek islands off the coast of ancient Caria and Lydia, once ruled by the Knights of St. John, and now called Dodekanesos (‘twelve islands’), which enjoy autonomy under Turkish suzerainty.

Steaming to the W.N.W. we cross the inland sea of the ancient Doris, between Rhodes and Cos, noted for its sponge-fishery. On our right lies the Anatolian peninsula of the ancient Chersonesus Rhodia, with Cape Alupo (Cynossema) and the island of Symi (Syme); to the W. rise the precipitous and fissured island of Telos (Tilos; 2008 ft.) and the volcanic island of Nisyros (2268 ft.), with its huge, still smoking crater and its hot springs. To the N.W. stretch the long outlines of Chersonesus Cnidia, with the ruins of Cnidos and Cape Krio (Triopium Promontorium).

The steamer rounds the E. coast of Cos (2871 ft.; Turk. Istankiöi; not one of the Dodekanesos group), once the seat of the most ancient shrine of Æsculapius and of a famous medical school (Hippocrates), and passes the peninsula of Budrum (Halicarnassus). To the W. appear in succession the islands of Kalymnos (2248 ft.), Leros (1086 ft.), Lipso (902 ft.; Lepsia), and Arki (Acrite).

To the E. of the island of Gaïdaronisi (696 ft.; Tragia), where Cæsar was captured by pirates in 76 B. C., opens the Latmian Bay, belonging to the ancient Ionia, now silted up by the deposits of the Mæander. A little inland are the ruins of Miletus and Priene.

The French steamers now pass through the Straits of Samos, between the Samsun Dagh (4150 ft.; Mykale) and the island of Samos, whose old capital, Samos, now Tigani, with its walls of the age of Polycrates and its new harbour (1908), is seen in the distance.

Vathy (Xenodochion Hegemonia tēs Samu, a good inn; pop. 9500), the new capital of Samos, lies in the bay of Scalanova (set below), on the N. coast. Above the narrow bay rises the distant Samsun Dagh. On the shore stands the plain palace of the Samian princes. Since 1832 the island has formed a Christian-Greek state under Turkey. The Museum, in the court of the high school, contains antiquities from the famous shrine of Hera and from Tigani.

The French vessels, soon after starting, offer a retrospect of Mt. Kerki (4725 ft.; Cerceteus Mons), the highest in Samos, and then cross the Bay of Scalanova (Sinus Caystrius). In the hill-country on the mainland, to the E. of this bay, near the mouth of the Cayster or Kaystros, once lay the rich Ionian towns of Ephesus and Colophon and, to the N. of these, Lebedus and Teos.

Passing the Bay of Sighajik and Cape Koraca (Carycium Promontorium) we soon reach the Straits of Chios (comp. p. 492).

Smyrna, see p. 530; voyage thence to Constantinople, see p. 533.

76. From Alexandria to Athens and Smyrna (and Constantinople).

From Alexandria to the Piræus (Athens: 590 M.): 1. Khedivial Mail Steamship Co. (Alexandria and Constantinople line), from Alexandria on Wed. (returning from the Piræus Thurs.) aft., in 42 hrs. (fare £ E 5 or £ 3 E 25 pias.).—2. Rumanian Mail Line (Alexandria and Constantza line), from Alexandria on Frid. aft. (returning from the Piræus Sat. aft.), in 2 days.—3. Russian Steam Navigation & Trading Co. (Odessa, Constantinople, and Alexandria line), from Alexandria on Frid. aft. (from the Piræus Tues.), in 2 days (130 or 90 fr.).

From Alexandria to Smyrna (623 M.), steamers of the Belgian company La Phocéenne (between Alexandria and Constantinople), every Sat. aft. viâ Rhodes, Leros, and Chios.

Agents in Alexandria, see p. 432; at the Piræus, p. 494; at Smyrna, p. 531. Passports for Turkey should be visés before starting, or a Turkish passport (teskeré) may be obtained at the government buildings (p. 434).

Alexandria, see p. 431. The Athens Steamers steer to the N.W. to the Strait of Kasos, 28 M. broad, lying between Kasos (1706 ft.; one of the Dodekanesos group, p. 490) and Crete (p. 415). Behind Kasos rises the lofty island of Kárpathos (4003 ft.; Ital. Scarpanto, Turk. Kerpe), like the former one of the southmost of the Sporades. Fine view of the Sitía Mts. (4852 ft.), continued by the Lasithi Mts., together called Dikte in ancient times. Off the E. coast of Crete we see the flat islet of Elasa.

We steer close by Cape Sídero (lighthouse), the N.E. point of Crete, and past the Gianitsades (Insulae Dionysiades). As we steam across the Cretan Sea (Mare Creticum) the high mountains of Crete long remain visible.

We next pass Askania (469 ft.) and Christiana (916 ft.), the southmost islets of the Cyclades (p. xxxii), which belong to Greece, and which, like the S. Sporades (p. 490) in the Ægean Sea, rise from a submarine barrier running between the extremities of Attica and Eubœa (p. 529) and the coast of Asia Minor.

Beyond Christiana we have a striking view of the immense prehistoric crater-basin formed by the islands of Therasía (952 ft.) and Santorin (p. 417). To the N. appear the wild rocky island of Síkinos (1480 ft.) and the distant Iós or Niós (p. 417), and to the N.W. Pholégandros (1349 ft.) and the large volcanic island of Melos or Milos (2537 ft.).

We steer between Pholégandros on the right and Polinos (1171 ft.) on the left, a broad passage marked by lighthouses at night, and then through the strait between Kímolos (1306 ft.) on the left and Siphnos (2280 ft.; lighthouse) on the right, both of which, like Sériphos (1585 ft.; on the right; with iron-mines), have retained their ancient Greek names.

Passing at some distance from Thermiá (1148 ft.; the ancient Kythnos) and Kea (p. 529) we steer close by the islet of Hágios Georgios and through the Bay of Ægina to the Piraeus (p. 494).

On the Voyage to Smyrna we steam to the N.N.W., 370 M. from Alexandria, to Rhodes (p. 490).

Beyond Rhodes on the left are the island of Charki (1954 ft.), off its N.W. coast, and then Telos and Nisyros (p. 490). A little farther on we pass through the strait between the Syrina Group, on the left, and the islets of Kandelëusa and Pantelëusa (181 ft.; lighthouse), adjoining Nisyros, on the right.

To the W. we sight the double-peaked island of Astropalia (1660 ft.; ancient Astypalaea) and Amorgós (p. 417), and to the E. Cos and Kalymnos (p. 490). Beyond the lights on the islet of Lévitha (548 ft.) and beyond Leros (p. 490), at which the steamer calls, the rocky isle of Patmos or Patínos (870 ft.), St. John’s place of exile, becomes more conspicuous.

We next steer round Cape Papas, the W. point of the bold island of Nikaria or Ikaria (3422 ft.), and then to the N.N.E. through the Straits of Chios, 4½ M. in breadth, between the island of Chios (Turk. Sakis Adasi; 318 sq. M. in area) and the mainland of Anatolia or Asia Minor. The S. entrance of the straits, beyond Capo Bianco (right; once Argennon), is flanked with the islets of Páspargon (lighthouse) and Panagia. On the right lies the harbour of Cheshmeh, a little town with a mediæval castle.

We now enter the harbour of Kastro, or Chios (Xenodochion Nea Chios, a good inn; pop. about 14,000, mostly Greeks), the capital of the island, on the E. coast. Once a most important member of the Ionian league of cities, Chios belonged in the middle ages to the Venetians (1204–1345), and then to the Genoese (1346–1566), and only became Turkish under Suleiman the Great (p. 542). The fruitless Greek struggle for independence ended with the massacre of Chios in 1832. The hill-country of Chios is extremely fertile. A valuable export is the gum of the mastic-shrub.

We next pass close to the Goni Islands, lying in front of the bay of Lytri (Erythrae), and the Spalmatori Islets (Œnussae Insulae), at the N. end of the straits of Chios.

Sail up the Gulf of Smyrna, see p. 530.

77. From (Marseilles, Genoa) Naples to Athens (and Constantinople).

774 M. From Naples to Athens (steamboat-agents at Marseilles, see p. 120; at Genoa, p. 114; at Naples, p. 137; at the Piræus, pp. 494, 495). 1. North German Lloyd (Mediterranean & Levant Service, RR. 23, 24, 80) from Marseilles every other Thurs. viâ Genoa (Sat.), Naples (Mon.), and Catania (Tues.) to the Piræus in 6 days (fare from Marseilles 180 or 120 marks, from Genoa 168 or 112 marks, from Naples 120 or 84 marks, from Catania 96 or 64 marks).—2. Messageries Maritimes (Marseilles, Constantinople, and Beirut line), from Marseilles every second Thurs. viâ Naples (Sat.) to the Piræus in 4 days (fare 225 or 150 fr.); also (Marseilles, Constantinople, and Black Sea line) every second Sat. viâ Kalamata and Canea (p. 415) to the Piræus in 5 days.—3. Società Nazionale, lines X and XI (Genoa, Constantinople, and Odessa line), from Genoa, Tues. night, viâ Leghorn (p. 143), Naples (Frid.), Palermo (p. 147), Messina, Catania, and Canea (p. 415) to the Piræus in 11 days (fare from Naples 155 fr. 50 c. or 109 fr.).

From Marseilles and Genoa to Naples, see RR. 23, 24.

From Naples (see R. 27), after half-a-day’s sail, we reach the superb Straits of Messina. On the right, at the foot of the Monti Peloritani, lie the ruins of Messina (p. 156); to the left is Reggio (p. 159); to the S.W. towers Mt. Ætna (p. 159).

The German and Italian boats steer to the S.S.W. to Catania (p. 160).

Sailing to the E.S.E., and gradually leaving Ætna behind, we lose sight of land for a whole day. At length, on the left, we sight the Messenian Peninsula of the Peloponnesus, flanked by the Œnussae Islands; beyond it, the Bay of Koronē, the ancient Messenian Bay, runs far inland. We then steer to the E. towards Cape Taenaron or Matapán (p. xxxii), the S. point of the peninsula of Mani. To the N.E. looms the bold rocky crest of Mt. Taygetos (7903 ft.), whose top is free from snow in summer only.

Beyond Cape Tænaron the Bay of Marathonisi, the ancient Sinus Laconicus, opens to the N. We next pass between Cape Maléa, notorious for its storms, and the island of Kythera (1660 ft.; Ital. Cerigo), and turn towards the N. For a short time we see the mountains of Crete (p. 415) to the S.E. The bleak S.E. coast of the Peloponnesus is now gradually left behind, while to the right a few small rocky islands, belonging to the Cyclades (p. 492), come into sight.

Off Hydra (1942 ft.; lighthouse), near the peninsula of Argolis, opens the Bay of Ægina, the ancient Saronic Gulf. To the left is the island of Poros; in the background rises Mt. Hágios Elias (1748 ft.), the highest hill in Ægina. On the right, beyond the islet of Hagios Geōrgios (1050 ft.; lighthouse), the ancient Belbina, appears the hilly S. extremity of Attica with Cape Colonna (p. 529). The barren rounded hill in Attica, much foreshortened at first, is Mt. Hymettos; straight in front of us is Mt. Parnes, forming the N. boundary of the Attic plain.

Before us are the ancient Mt. Ægaleos (now Skaramangá Mts.) and the indented coast of the island of Salamis, which appears at both ends to join the mainland. Above Salamis towers the lofty peak of Geraneia in Megaris. A hill jutting into the sea in front of Mt. Ægaleos now becomes visible. This is the Piraeus Peninsula (comp. Map, p. 528). The hill a short way inland is the Munychia (p. 495), and to the right of it lies the shallow bay of Phálēron (p. 528). Between Hymettus and Parnes the gable-shaped Pentelikon appears. We now have a beautiful view of Athens; in the centre rises the Acropolis, on the left the monument of Philopappos. The large white building on the right is the royal palace, beyond which rises Lykabettos (p. 528).

As we near the Piræus we observe the rocky islet of Lipsokutáli (Psyttaleia; lighthouse), lying off the E. tongue of Salamis, and masking the entrance to the straits of Salamis, the scene of the famous battle of 480 B. C. (p. 506). The steamer rounds the headland of Aktē and slowly enters the harbour of the Piræus.

Piræus.—The Commissionnaires of the chief Athens hotels come on board (those of the smaller, only when written for). Arrangements for landing (boat 1 dr., with baggage 2 dr.) and for a carriage to Athens (p. 495) had better be left to them. Heavier baggage is briefly examined at the Teloníon, at the S. E. angle of the harbour.

Station of the electric railway to Athens (comp. p. 503), to the N. of the town (opposite the station of the Peloponnesus line).

Hotel. Hot. & Restaurant Continental, Karaïskakis Sq., to the N. of the harbour, R. from 2 dr.; but better quarters are to be had in Athens.—Cafés in and near the garden to the S. of the Dēmarchía, 3 min. to the E. of Karaïskakis Sq., on the harbour.

Electric Tramways from the custom-house to the Athens station; from the station to the Zea harbour; also from the station, from the harbour (Karaïskakis Sq.), or from the Rue de Socrate to New Phálēron (p. 528).

Steamboat Agents. Messageries Maritimes, Vamvakaris, Rue de Miaulis 30 b; North German Lloyd, Roth & Co., Rue de Tsamadú 21; German Levant, Frangopulos; Austrian Lloyd, S. Calucci, Quai de Tshelebi, to the W. of Karaïskakis Sq.; Società Nazionale, A. Vellas; Russian Steam Navigation & Trading Co., Mussuris.

British Consul, C. J. Cooke; vice-consul, J. Joannidis.

The Piraeus, Gr. Peiraieus (pronounced Piræévs; pop. 71,500), the time-honoured seaport of Athens (comp. p. 506), became a mere village after its destruction by Sulla in 86 B. C., and in the middle ages even lost its name, but within the last few decades has developed into a prosperous town. Its trade now exceeds that of Patras. The harbour, the ancient Kantharos, admits the largest vessels. Spacious quays, an exchange, a theatre, wide and regular streets, and over a hundred factories have been constructed.

Its antiquities are few compared with those of Athens. The chief are parts of the fortifications, such as a wall defended by towers, ascending the peninsula of Eétioneia, to the W. of the harbour. It is reached from the station in 8 min. by walking round the shallow N. arm of the harbour (the ‘blind harbour’ of antiquity). On the hill it is pierced by a gateway between two round towers.

A broad and easy path ascends the Munychia Hill (280 ft.), to the E. of the town (20 min.), whence we overlook the various basins of the Great Harbour, the round Zea Bay at the S.W. foot of the hill, the Munychia Harbour at the S.E. base, and to the E. of the latter the broad Phaleron Bay, where the Athenian ships lay down to the time of the Persian wars. We may return by the Zea Bay, noticing remains of ancient boat-houses at the beginning of the Rue du Serangeion, and regain the station by tramway.

From the Piræus to Athens (5 M.) the electric Railway (p. 503) is the quickest conveyance, but as it lies low and runs through cuttings and tunnels near the city it affords little view.

New-comers had better take a Carriage. The new route (1½ hr.; fare, with luggage, 8–10 dr.), though longer, is in better condition, and is therefore preferred by the drivers. At first running alongside the railway it reaches New Phaleron (p. 528); it then skirts the bay of Phaleron at some little distance from the shore. Later proceeding inland it follows the broad new Boulevard Syngrós, which commands an excellent view of the Acropolis and leads in a straight line as far as the Olympieion (p. 509).—The old route (1¼ hr.; fare, with luggage, 6–7 dr.) follows the ‘Long Walls’ (p. 506) which once connected the Piræus with Athens. On the left is Mt. Ægaleos (p. 494), while on the right appears the bay of Phaleron. We cross the generally dry bed of the Kephisos (p. 505), and then pass the limits of the ancient olive-grove that occupies the plain of the Kephisos. Leaving behind a hill which conceals the Acropolis we at once come in sight of the Theseion, the Areopagus, and the Acropolis. The houses of the city, which we reach at the Dipylon (p. 522), all too soon exclude this splendid view. Athens, see p. 502.