The churches in the N.E. Quarter, such as Omnium Sanctorum (Pl. B, 3), San Marcos (Pl. C, 2), and Santa Marina (Pl. B, 2) still possess towers in the Moorish style, which were once the minarets of mosques.—The so-called Casa del Duque de Alba (Pl. C, 2), Calle de las Dueñas 5, a palace built for the Riberas (p. 65) in the Mudejar style after 1483, contains a court planted with palms and a staircase richly adorned with azulejos, but the house itself is not shown.

In the Calle de Santa Paula, a little to the E. of San Marcos, is the Convento de Santa Paula (Pl. C, 1, 2), a nunnery founded in 1476. The forecourt has a superb Gothic portal, with terracotta ornamentation by Franc. Nicoluso of Pisa and reliefs of saints by Pedro Millán (p. 63). The rich mural azulejos (16th cent.) in the church’ are well worth seeing.

In the Ronda de Capuchinos (Pl. A, 1, 2) there are considerable remains of the ancient City Wall, with its external towers and low parapet (‘barbacana’, after Byzantine models).

c. The Western and South-Western Quarters.

Starting from the small Plaza del Pacífico (Pl. D, 4), planted with orange-trees, we follow the Calle de San Pablo to the S.W. as far as the church of Santa Magdalena (Pl. D, 4) and then turn to the right into the Calle de Bailén. From this in turn we again diverge to the right and follow the Calle de Miguel de Carvajal to the Plaza del Museo (Pl. D, 5; officially, Plaza de la Condesa de Casa Galindo), in which rises a Bronze Statue of Murillo.

The *Museo Provincial (Pl. D, 5; adm., see p. 60), occupying an old monastery of Mercenarii (Convento de la Merced), contains the small Museo Arqueológico and the Museo de Pinturas, a famous picture-gallery. The gallery contains several valuable sculptures, but its chief treasure consists in 23 Murillos, mostly from the old Capuchin monastery (Pl. A, B, 1), depicting the legend of St. Francis of Assisi and the foundation of the Franciscan order.

A small court leads to the N. Cloisters, where the antiques (Roman, Visigothic, Moorish), along with some modern works, are exhibited. From the nearer aisle of the cloisters an azulejos-portal leads straight into the—

Great Hall of the picture-gallery, once the convent-church. The **Murillos are all hung on the walls of the nave. On the S. wall, by the entrance, note specially the Concepción, the Annunciation, SS. Leander and Bonaventura, and the ‘Virgen de la Servilleta’, said to have been painted on a table-napkin. On the N. wall we note St. Felix of Cantalicio with the Infant Jesus, the *Almsgiving of St. Thomas of Villanueva, the great Conception, the Adoration or the Shepherds, and Christ on the Cross embracing St. Francis.

On the end-wall of the church is the Martyrdom of St. Andrew by Roelas. The transept and choir are hung with numerous pictures by Zurbarán (notably the Triumph of St. Thomas Aquinas, in the choir). Here, too, are several *Sculptures: Pietro Torrigiani, Virgin and Child, with the penitent St. Jerome (in terracotta); Montañés, wooden figures of the Virgin and Child, John the Baptist, and St. Dominicus.

A room on the Upper Floor contains modern pictures.

The Calle de los Reyes Católicos, in line with the Calle de San Pablo (p. 66), ends at the Puente de Isabel Segunda (Pl. F, 6), the chief bridge crossing to the suburb of Triana.

A little short of the bridge we turn to the left and follow the Paseo de Cristóbal Colón (Pl. E, F, 5, 4), skirting the left bank of the Guadalquivir and the quays. On the left lie the Bull Ring (Pl. F, 4, 5); then the pretty Plaza de Atarazanas (Pl. F, 4; Arabic Dâr as-San῾a, ‘arsenal’, ‘place of work’), on the site of the old Moorish wharf, where the great Artillery Arsenal (Maestranza), the Hospital de la Caridad, and the Custom House (Aduana), are now situated.

The Hospital de la Caridad (Pl. F, 4; adm., see p. 60), erected for the ‘brotherhood of charity’ (Hermandad de la Caridad) in 1661–4, possesses, in its baroque church, six far-famed **Murillos (1660–74). Two of these in particular are the delight and admiration of every beholder: Moses striking the Rock (Cuadro de las Aguas, or La Sed, ‘the thirst’) and the Feeding of the Five Thousand (Pan y Peces, ‘bread and fishes’). Besides these pictures there are, on the left, the Infant Christ, the Annunciation, and San Juan de Dios carrying sick persons into the hospital; on the right, the young John the Baptist. By tho high-choir are two singular but repulsive pictures by Juan Valdés Leal (1630–91), the Raising of the Cross and the Triumph of Death.

Near the S. angle of the Plaza, close to the river, rises the Torre del Oro (Pl. G, 4), once a fortified tower of the Moorish Alcázar (p. 61), and ever since called the ‘tower of gold’ on account of its brilliant azulejos. The upper part of the tower dates from the Christian period only; the window openings and the balconies were constructed in 1760.

Near the Torre del Oro begin the *Public Gardens of Seville, which, particularly in spring, when roses, camellias, and orange-blossom are in their glory, afford a delightful promenade. The favourite part is the Paseo de las Delicias (Pl. H, 3), beginning at the Palacio de Santelmo (Pl. G, 3; now a priests’ seminary), where the people of fashion drive on fine afternoons. On the way back we may walk through the Parque María Luisa (Pl. H, 2), once part of the Santelmo gardens, and regain the town by the Calle San Fernando, passing the great Tobacco Factory (Pl. G, 3), a huge baroque building of 1757.

8. From Seville to Cordova.

81½ M. Railway (Seville and Madrid Line) in 2¾–4¾ hrs. (fares 16 p. 40, 12 p. 30, 7 p. 40 c.); one train de luxe daily, 1st cl. only, fare 10 per cent higher. Trains start from the Estación de Córdoba.

Seville, see p. 59. We follow the Guadalquivir upstream, at some distance from its lofty reddish banks, which are visible at times. Nearing (13½ M.) Brenes we enjoy a last retrospect of the cathedral of Seville with the Giralda.

22 M. Tocina, the junction for Mérida and Lisbon. Beyond (25½ M.) Guadajoz we cross to the right bank of the Guadalquivir. 46½ M. Peñaflor, adjoining rapids of the river which drive large mills. 49 M. Palma del Río, at the confluence of the Guadalquivir with the Genil (p. 74). 67½ M. Almodóvar, with a loftily situated Moorish castle, now being restored.

81½ M. Cordova.—At the Station (Estación de Madrid, Sevilla y Málaga; Pl. B, C, 1; Rail. Restaur.) are omnibuses from the chief hotels.

Hotels (comp. p. 51; charges should be arranged beforehand). Hot. Suizo (Pl. a; C, 2), corner of Calle Duque de Hornachuelos and the narrow Calle Diego León, pens, from 12½ p., variously judged.—Less expensive: Hot. de Oriente (Pl. c; C, 2), pens. 8–10 p.; Hot. de España & Francia (Pl. b; C, 2), pens. 8 p.; Hot. Simón (Pl. d; C, 2), pens. 5–6 p., very fair; these three are in the Paseo del Gran Capitán; Cuatro Naciones, Calle San Miguel 4.

Cafés. Café-Restaur. Suizo, Calle Ambrosio de Morales (Pl. D, 3); La Perla, Calle del Conde de Gondomar No. 1, Cervecería Alemana No. 8.

Post & Telegraph Office (Pl. D, 3), Plazuela de Seneca.

British Vice-Consul, Richard Eshott Carr.

Half-a-Day, when time presses: Cathedral (open all day, except 12–2; closes 2 hrs. before sunset); visit to the Mihrâb, Renaissance choir, Mudejar chapel, etc., for which a permiso (2 p.) is obtained at the Oficina de la Obrería, adjoining the Puerta del Perdón; then the Guadalquivir Bridge, with the Calahorra; the Paseo del Gran Capitán and Jardines de la Victoria.

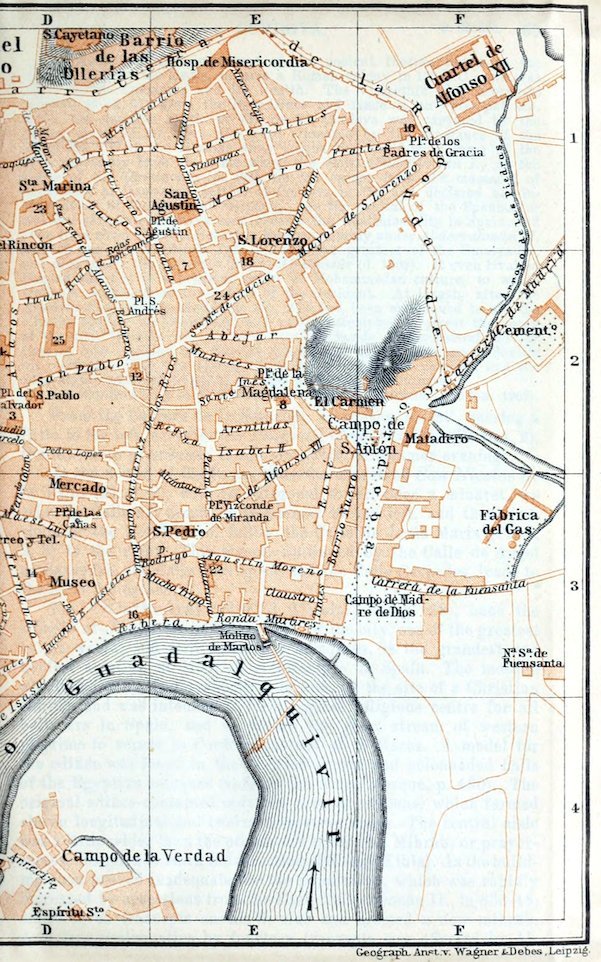

Cordŏva, Span. Córdoba (391 ft.), a provincial capital and the seat of a bishop, with 60,000 inhab., lies at the foot of the Sierra de Córdoba, a spur of the Sierra Morena, in a plain sloping gently down to the Guadalquivir. The town, whose ancient glory has long departed, now contains little or nothing to interest the expectant traveller except the mosque, now the Cathedral, which in spite of many later additions and disfigurements, is still the grandest monument in Spain of the Moorish period. Other memorials of this Mecca of the Occident, once famous as a patroness of science also, now survive only in several portals and inscriptions.

Corduba, the most important of the ancient Iberian towns on the upper course of the Bætis, became a Roman colony in 152 B.C., and was noted for its commerce and its wealth. The Visigothic king Leovigild wrested it in 571 from the Byzantines and made it an episcopal see. After the decisive battle of 711 (p. 51) Cordova was captured by the Moors, aided by the Jews who were alienated by the arrogance of the Visigoths. With the Moorish sway begins the world-wide fame of the city, especially from the time when the emir Abderrahmân I., of the house of the Omaiyades (p. 485), on his escape from the massacre of his family at Damascus, settled at Cordova in 756 and declared his independence of the Oriental caliphate. As the capital of the Spanish or western caliphate, Cordova soon became the wealthiest city in Spain, and even for a short time the richest in Europe, notably under Abderrahmân II. (822–52) and Abderrahmân III. (912–61), the greatest of the Omaiyades, and also under the governor (hâjib) Al-Mansûr (d. 1002). It even rivalled Bagdad and Fez as a brilliant centre of Mohammedan culture, to which students flocked from every part of the Occident. At length, after the Almoravides and Almohades (p. 95), who had been summoned to aid the citizens against the Christians, had vainly attempted to arrest the decay of the city, Cordova fell, in 1236, into the hands of Ferdinand III. of Castile, who expelled the Moorish inhabitants and in 1248 made Seville his residence. The city afterwards fell into decay and poverty, and the once highly extolled Campiña became a desolate wilderness.

See ‘Cordova’, by A. F. Calvert and W. M. Gallichan (London, 1907).

From the Carrera de la Estación, or ‘station street’, bearing a little to the left, we enter the Paseo del Gran Capitán (Pl. C, 1, 2), the favourite promenade of the townsfolk on summer evenings.

At the S. end of the Paseo, near the church of San Nicolás de la Villa (Pl. C, 2), with its octagonal tower, once a minaret, we take the Calle del Conde de Gondomar to the left, and then, just short of the Hotel Suizo, follow the Calle de Jesús María (Pl. C, 2, 3) to the right. This street, continued by the Calle de Angel de Saavedra, the Calle Pedregosa, and the Calle Céspedes, leads to the S. to the cathedral.

The **Cathedral (Pl. C, 3, 4; adm., see p. 68), once the Mesjid al-Jâmia, or ‘chief mosque’ of the city, one of the greatest in the world, and still called La Mezquita, is the grandest and noblest creation of Moorish architecture in Spain. The mosque was founded by Abderrahmân I. in 785, on the site of a Christian church, and was intended to form a great religious centre for all believers in Spain, and to induce the great stream of western pilgrims to repair to Cordova instead of to Mecca. A model for the edifice was found in the arcaded courts and colonnaded halls of the Egyptian mosques (such as the Amru Mosque, p. 460). The original edifice contained only ten rows of columns, which formed eleven longitudinal and twelve transverse aisles. The central aisle was a little wider than the others and ended in a Mihrâb, or prayer-recess, designed to mark the direction of Mecca (Kibla). As the building soon proved inadequate for the population, which was rapidly increased by accessions from the East, Abderrahmân II., in 833–48, added seven transepts on the S. side and erected a new mihrâb. A further prolongation by fourteen transepts was effected by AlHâkim II. (961–76), after which the magnificent third mihrâb (mihrâb nuevo) formed the termination of the building. Though the mosque was now considered the finest in the Occident, rivalling the Kairuin mosque at Fez, it failed to satisfy the ambition of Al-Mansûr (p. 69). As the sloping ground on the S. side precluded extension in that direction, this governor, in 987–90, caused seven new rows of columns to be raised on the E. side, thus increasing the number of aisles to nineteen, but destroying the symmetrical plan of the building, which required the mihrâb, or holy of holies, to be in line with the main axis of the building.

After the conquest of Cordova by the Christians in 1236 (p. 69) the mosque was dedicated to the Virgin (Virgen de la Asunción). The Spaniards at first confined their operations to walling up most of the doors and then fitting up side-chapels along the walls. As the needs of the Christian ritual, however, soon demanded the construction of a choir (primitivo coro), part of the second mihrâb and the adjoining aisles had in 1260 to be demolished. Still greater damage was done by the insertion of the Renaissance choir in the centre of the building, and of the Sala Capitular, or sacristy, in the middle of the S. wall.

The Ground Plan forms an immense rectangle of about 575 by 427 ft., of which fully a third is occupied by the court. Court and church are surrounded by a fortress-like battlemented wall which, on three sides, rests on massive substructions. Nothing indicates the object of the building except the rich portals, flanked with niches and windows, and, on the N. side, adjoining the Calle del Obispo Herrero, the Campanario or bell-tower (305 ft. high), which was substituted for the Moorish minaret in 1593. Ascent of the tower interesting (adm. 25 c.; 255 steps).

The *Puerta del Perdón, the main gateway, restored in 1377 on the model of the gate of that name at Seville (p. 63), adjoins the clock-tower and leads into the—

*Patio de los Naranjos (‘orange-court’), once the court of the mosque, where the faithful performed their ablutions. Light and spacious, yet well-shaded by orange and palm-trees, watered by five fountains, and always enlivened with groups of quiet visitors, it presents a typical scene of Oriental repose. The avenues were originally laid out in line with the colonnades in the interior of the mosque. The old arcades of the court (claustro) are now walled up on the N. side. Of the nineteen gates on the S. side, two only, the Puerta de las Palmas, the chief entrance to the cathedral, and the small doorway of the eastmost colonnade are now open.

The *Interior of the Cathedral, in spite of its moderate height (37 ft.), and in spite of much disfigurement, is singularly impressive. In the subdued light the forest of columns seems endless. They average 13 ft. only in height, and are of the most diverse materials, many of them having been brought from late-Roman buildings or from Christian churches. The capitals show a marvellous wealth of design; their bases are buried in the pavement, the level of which has been raised by 11–14 inches in the course of centuries. The vast number of horseshoe arches which connect the columns, in the direction of the length of the church, and the upper semicircular arches resting on projecting pillars impart peculiar life to the building. The painted timber-ceilings of the different roofs have been restored in their original style. The sumptuous mosaic pavement has disappeared, and so too have the countless chandeliers and lamps which burned perpetually during the Moorish period.

The wealth of artistic decoration was lavished chiefly on the mihrâbs, the first of which has been entirely destroyed. The second and third were each provided with a vestibule and two side-rooms, part of which was formerly shut off to form the Caliph’s maksûra (or court-platform). The vestibule of the *Second Mihrâb, with its superb shell-vaulting, still exists.

The **Third Mihrâb is considered a marvel of art. The front is adorned with two rows of columns, one above the other, and with double toothed arches. The vestibule, now Capilla de San Pedro, and the prayer-niche itself, a kind of heptagonal chapel of barely 13 ft. in diameter, exhibit the most elaborate efforts of early-Moorish art, especially in the rich marble plinth and in the coloured glass mosaics executed by Byzantine artists. The toothed arches of the windows and the boldly interlacing arches of the superb dome point to a later high development of Moorish art.

Of the Christian Additions to the church one of the most noteworthy is the sumptuous Capilla Mudéjar de San Fernando, to the left of the second mihrâb, erected over the old royal vault. The *Renaissance Choir (Coro and Capilla Mayor), designed by Hernán Ruiz the Elder in 1523, was completed, with many alterations, in 1627. Though only 256 by 79 ft. in size, it is crowded with no less than 63 columns, and it rises high above the roof of the mosque. It is considered a masterpiece of the plateresque style, but has ruined the original symmetry of the mosque.

The Alcázar (Pl. C, 4; now a prison), erected in 1328, contains but scanty relics of the ancient Moorish castle.

The Calle Torrijos, on the W. side of the cathedral, descends to the Puerta del Puente, a triumphal arch of the time of Philip II., on the site of the Moorish bridge gateway. The Moorish *Bridge (Pl. C, D, 4) of sixteen arches, resting on Roman foundations, here unites Cordova with the S. suburb of Campo de la Verdad. Halfway across we have a fine view of the cathedral, and of a dam, up the river, with Moorish mills. The massive tête-de-pont, Calahorra (Iberian Calagurris), also is of Moorish origin.

Returning into the town from the bridge, we may next visit the Puerta Almodóvar (Pl. B, 3), a relic of the Moorish city-wall, and then walk through the Jardines de la Victoria to the station.

9. From Cordova viâ Bobadilla to Granada.

153 M. Railway in 6¼–8½ hrs. (fares 36 p. 30, 28 p. 20, 19 p. 30 c.); express on Mon. & Frid. only; change at Bobadilla (Railway Restaurant). Beyond Bobadilla views to the right.

Cordova, see p. 68.—The train crosses the Guadalquivir and runs through a dreary hill-country (Campiña). Looking back, we see Cordova, the Sierra of Cordova, and Almodóvar (p. 68).

We cross the Guadajoz several times. Beyond (21 M.) Fernán Núñez the vine and olive culture begins. 31 M. Montilla (1165 ft.), once famed for its Amontillado, resembling the wine of Xeres (p. 59). Farther on, to the left, we have a view of the distant Sierra Nevada (p. 49).

47 M. Puente Genil (Rail. Restaur.). The town lies 2 M. to the N.W., and is seen to the right as we cross a lofty bridge over the Genil (see below). The train ascends to the plateau of the Sierra de Yeguas, in view, farther on, of abrupt Jurassic mountains.

62 M. La Roda, junction for Utrera. (Lines to Cadiz and Seville, see R. 6.)

Running to the S.W. the train soon reaches the watershed (1477 ft.) between the Guadalquivir and the Guadalhorce. Beyond (69½ M.) Fuente Piedra we observe on the right the Laguna Salada, a salt-lake resembling the shotts of N. Africa (p. 169).

77 M. Bobadilla, see p. 57.

The Granada train diverges to the N.E. from the Málaga line (R. 11), and ascends the broad valley of the Guadalhorce. On the right soon appears the Sierra de Abdalajis.

87 M. Antequera (1346 ft.; Fonda de la Castaña and others), the Roman Anticaria, lies picturesquely at the N. base of the hills, with a ruined Moorish castle. The Cueva de Menga, 10 min. to the E. of the town, is one of the largest dolmens in Spain.

99½ M. Archidona; the town lies on a hill, 3¾ M. to the S.—We next cross the watershed between the Guadalhorce and the Genil and descend through several tunnels. After the third the snow-covered Sierra Nevada suddenly appears towards the E.

121 M. Loga, the Lôsha of the Moors, together with Alhama, a little town on the hill 12½ M. to the S.E., once ‘the keys of Granada’, were captured by the Catholic kings (p. 75) in 1488.

The country is now hilly and at places sandy; the Genil with its Vega (p. 73) remains on the right. 132 M. Tocón, at the foot of the Sierra de Prugo, On the left rises the bare Sierra de Parapanda, which the natives of Granada regard as a barometer. 144 M. Pinos Puente, at the foot of the barren Sierra de Elvira.

We next enter the fertile Vega, enclosed by olive-clad hills. 148 M. Atarfe, station for Santa Fe, 3 M. to the S.W., on the left bank of the Genil, built in the form of a Roman camp by Isabella the Catholic during the siege of Granada. The capitulation was signed here in 1491 (p. 75), and so too, in 1492, was the contract with Columbus regarding his voyage of discovery (p. 5).

In the foreground appears the lofty Albaicín (p. 74); then, overtopped by the Sierra Nevada, (153 M.) Granada (see below).

10. Granada.

The Station (Estación de los Ferrocarriles Andaluces; Pl. B, 6; no buffet) is 1¾ M. from the hotels in the Puerta Real and nearly 2 M. from those near the Alhambra. Hotel-omnibus to the former 1, to the latter 2 p.; an ‘omnibus general’ (50 c. each pers. or each trunk) plies to the Despacho Central (p. 51), opposite the Hot. Victoria.

Hotels (comp. p. 51). Near the Alhambra, in the Alhambra Park, a beautiful, but in winter a cold situation, ¾ M. above the town (2–3 min. from the hill-tramway station; see below): Hot. Washington Irving (Pl. b; F, 2), with the dépendance Siete Suelos (Pl. c; F, 2), patronized by English and Americans; Alhambra Palace Hotel (Pl. a; F, 3), new, R. 6–12½, pens. 20–35 p.; *Pens. Miss Laird, Carmen de Bella Vista, with garden, 8½–12 p. per day; Hot. del Bosque de la Alhambra, at the N. base of the Alhambra Hill, below the Torre de Comares (Pl. E, 2), pens. 8–15 p., well spoken of.—In the Town (ca. 1¾ M. from the Alhambra): *Hot. Alameda (Pl. d; F, 5), adjoining the shady Carrera del Genil, with view of the Sierra Nevada, pens. 8–20 p.; Hot. de Paris (Pl. e; E, 4), Gran Via de Colón 5, with terrace, restaurant, etc., pens. 9–20 p.; Hot. Victoria, on the W. side of the Puerta Real, with fine view, pens. from 8 p., Spanish, quite good; Hot. Nuevo Oriente (Pl. g; E, 5), Plaza de Cánovas del Castillo 8, pens. 7 p., quite Spanish, very fair; Fonda Navío, Calle Martínez Campos (Pl. E, 5), with a favourite restaurant.—Drinking-water not good.

Cafés. Café Colón, Calle de los Reyes Católicos (Pl. E, 4); Imperial, Carrera del Genil (Pl. F, 5).

Tramways. 1. Plaza Nueva (Pl. E, 4)-Cocheras (red disc): through the Calle de los Reyes Católicos (Pl. E, 4, 5) to the Puerta Real, the University (Pl. D, 5), and the Rail. Station (Pl. B, A, 6).—2. Plaza Nueva-Cervantes (yellow): viâ the Puerta Real and the Carrera del Genil to the Paseo de la Bomba (Pl. G, H, 4).—3. Puerta Real (Pl. E, 5)-Vistillas-Alhambra (green): viâ the Plaza Nueva to the Puerta de los Molinos (Pl. G, 3; change), then by the hill-tramway (rack-and-pinion) to the Alhambra Park (Cuesta de las Cruces; Pl. F, 2, 3), in ¼ hr.; fare 30 c.

Cabs (stationed in the Carrera del Genil). Drive in the town, with one horse 1, with two horses 2½ p.; per hour 2 or 3 p.—To the Alhambra, Albaicín (p. 79), and Sacro Monte (p. 78) 5 p. extra (but bargain advisable). Carr. and pair may be had also from the Despacho Central or the Alhambra hotels (3 p. per hour).

Post & Telegraph Office (Correo; Pl. E, 4), Calle de los Reyes Católicos. Post-office open 10–12 and after 2; poste restante letters delivered 1 hr. after arrival of trains.

British Vice-Consul, Chas. E. S. Davenhill.

Sights. Alhambra (p. 79), daily, 9–12 and 1–6, adm. 50 c.–1 p., on Sun. free; some rooms specially shown by the custodian.—Generalife (p. 87), best by morning light; tickets (papeletas) at the Casa de los Tiros (p. 77), on week-days, 9–11, free.—The Cathedral (p. 76), daily, closed between 11 and 2.30; the Capilla Real (p. 76), either in the morning before high-mass (in winter at 10, in summer at 9), or 2.30 to 4, in summer 3–5 p.m.—The smaller churches are usually open from an early hour till 8.30 or 9 only, but are shown later by the sacristan (fee).—The usual hours for other sights are 8–12 and 2–6; between 12 and 2 a substantial fee is exacted.

Promenades. In winter, Carrera del Genil (p. 77), 3–5; in summer, Paseo del Salón (p. 77) and Paseo de la Bomba, 5–7. Band on Sun. and Thurs.

Guides at the hotels, needless except when time presses. Those who pester strangers in the streets and at the entrance to the Alhambra, as well as gipsy beggars, should be disregarded.

Chief Attractions (two days). 1st. Forenoon: the Cathedral (p. 76); Placeta de la Lonja (p. 77); Casa de los Tiros (p. 77); Carrera del Genil; *Paseo del Salón; afternoon: Alameda del Darro (p. 78); *View from San Nicolás (p. 79) or from San Miguel el Alto (p. 79).—2nd. *Alhambra (p. 79) and Generalife (p. 87).

Granáda (2195 ft.; pop. 69,000), once the capital of the Moorish kingdom, and now that of the province of Granada, the residence of an archbishop and seat of a university, lies most picturesquely at the foot of two hills (about 490 ft. high), which gradually slope to the E. up to the Cerro del Sol, and descend abruptly to the fertile, well-watered river-plain of the Vega. The Albaicín, the northmost of the two hills, the oldest quarter of Granada, once the residence of the Moorish aristocracy, but now inhabited chiefly by gipsies, forms a town by itself. The deep ravine of the Darro, which is generally dry as its water is much diverted for irrigation purposes, separates the Albaicín from the Monte de la Assabica, or Alhambra Hill to the S. (comp. p. 79). The Darro, descending from the N.E., turns to the S. near the Alhambra Hill and falls into the more important Genil.

The two hills were once occupied by Iberian and then by Roman settlements, the one on the Albaicín having perhaps already borne the name of Garnata. Soon after 711 the Moors built the ‘Old Castle’ (Al-Kasaba al-Kadîma) on the site of Garnata. After the decline of the caliphate of Cordova (p. 69) Zâwi ibn Zîri, the governor of Granada, declared himself independent in 1031, and founded here the dynasty of the Zirites, which, however, was overthrown by the Almoravides (p. 95) in 1090. As the power of the Almohades (p. 95) declined the native governors revolted anew. At length in 1246 Granada became the seat of the Nasride Dynasty founded by Al-Ahmar (‘Mohammed I.‘), which, after the fall of Seville, succeeded, in alliance alternately with the Castilians and the Merinides (p. 95), in retaining possession of Granada, Málaga, and Almería for nearly 250 years. Mohammed I. offered an asylum in Granada to the Moors who were expelled from Cordova, Valencia, and Seville, and began the building of the ‘New Castle’ (Al-Kasaba al-Jedîda) on the hill of the Alhambra. His successors afterwards created the Alhambra Palace, the most sumptuous of royal residences. Thanks to their fostering care for agriculture and industry, for science, art and architecture, Granada attained such brilliant prosperity as even to eclipse the fame of the old caliphate of Cordova.

The downfall of the kingdom of Granada was at length brought about by party struggles between the Zegri, the Beni Serrâj (the Abencerrages of legend; comp. p. 84), and other noble families, and by quarrels between king Mulei Abu’l-Hasan (d. 1485) and his son Boabdil; a welcome opportunity was thus afforded to Ferdinand and Isabella, the so-called ‘Catholic Kings’, of intervening and thus gaining their life-long object of destroying the last Moorish kingdom in Spain. After the death of his father Boabdil remained inactive when Ferdinand proceeded to besiege Málaga (p. 90); he made one despairing attempt at resistance when the Spaniards demanded the evacuation of Granada, but in 1491 had to conclude a humiliating peace. He soon afterwards crossed the Sierra Nevada and retired to Tlemcen in N. Africa (p. 187), where he ended his inglorious career. With the Spanish domination began the decay of the city; it was depopulated by the decrees of the Catholic Kings, the Inquisition held fearful sway here, and ere long Granada became a ‘living ruin’. Within the last few years, however, the busy tourist traffic, the establishment of sugar-factories, and the prosperous mining industry of the Sierra Nevada have somewhat repaired the fortunes of the city, and several of the old quarters have been entirely modernized. But its picturesque history, its memorials of the most glorious period of Moorish culture and art, and the striking view of the snow-mountains it affords will ever render it the most fascinating goal of travellers in Andalusia.

See ‘Granada: Memories, Adventures, Studies, and Impressions’, by Leonard Williams (London, 1906); and ‘Granada and the Alhambra’, by A. F. Calvert (London, 1907).

a. The Lower Town.

Leaving the railway-station (Pl. B, 6; tramway No. 1, see p. 73), we follow the Calle Real de San Lázaro to the S.E. to the Paseo del Triunfo (Pl. C, 4), so named from the column in honour of the Virgin (triunfo). Here, by the half-ruined Puerta de Elvira (Pl. C, 4), begin the old Calle de Elvira and the new Gran Via de Colón (Pl. C-E, 4), both leading to the chief artery of traffic, the narrow—

Calle de los Reyes Católicos (Pl. E, 4, 5), which is built above the Darro, and connects the busy Puerta Real (Pl. E, 5), to the S.W., with the Plaza Nueva (Pl. E, 4; officially, Plaza Rodriguez Bolivar), to the N.E., at the foot of the Alhambra Hill (p. 79).

In the Calle de Lopez Rubio, a side-street, is the so-called Casa del Carbón, once a Moorish granary, with picturesque horseshoe arches and stalactite vaulting. To the S.W. of it is the modern town-hall (Ayuntamiento).

The short streets on the opposite side lead to the Alcaicería, (Pl. E, 4, 5), with its numerous columns, which was burned down in 1843, once a Moorish market-hall (Al-Kaisariya), resembling the Oriental sûks (p. 335), and to the modernized Plaza de Bibarrambla (Pl. E, 5), named after a Moorish city-gate which once stood here. A few paces from these lies the Placeta de las Pasiegas. Here, surrounded by buildings which mar its effect, rises the—

*Cathedral (Pl. D, E, 4, 5), an imposing memorial of the conquest of Spain, and the finest Renaissance church in the kingdom. It was begun in 1523 by Enrique de Egas in the Gothic style, continued in 1525 by Diego de Siloe (d. 1533) in the plateresque style (p. 51), and consecrated, while still unfinished, in 1561. The N. tower only, which is now 187 ft. high, has been erected; the huge façade was begun in 1667 by Alonso Cano, who was also the chief author of the sculpture and painting in the church; the interior was not completed till 1703.

Two of the Side Portals, the Puerta de San Jerónimo, the first entrance to the N. in the Calle de Jiménez de Cisneros, and the Puerta del Colegio, on the E. side of the ambulatory, are adorned with sculptures by Siloe and others. The *Puerta del Perdón, the second portal to the N., also owes the beautiful ornamentation of its lower part to Siloe.

The *Interior (adm., see p. 74) has double aisles with two rows of chapels, a lofty transept which does not project beyond the side-walls, a central choir, and a Capilla Mayor with ambulatory. The vaulting, 100 ft. in height, is borne by massive pillars and half-columns. Total length 380, breadth 220 ft. The decoration in white and gold harmonizes well with the fine marble pavement (1775).

The *Capilla Mayor, 148 ft. long and 154 ft. high, is crowned with a dome resting on Corinthian columns. On the pillars in front of the marble high-altar are kneeling statues of the ‘Catholic Kings’, by Pedro de Mena and Medrano (1677); above them are painted *Busts of Adam and Eve, in oak, by Alonso Cano, who painted also the representation of the Seven Joys of Mary.

Side Chapels. The Capilla de San Miguel, on the right, lavishly decorated in 1807, contains a picture by Al. Cano, the Mater Dolorosa (after Gasp. Becerra).—In the Capilla de la Trinidad, beyond the door of the Sagrario (p. 77), is a painting of the Trinity by Al. Cano.—The Altar de Jesús Nazareno contains *Pictures by Dom. Theotocópuli (St. Francis) and Ribera; the fine Bearing of the Cross is by Al. Cano.—By the same artist are also the fine oaken busts of St. Paul and John the Baptist in the Capilla de Nuestra Señora del Carmen, adjoining the N. aisles.

From the first chapel in the ambulatory, to the right of the Puerta del Colegio, a portal by Siloe leads through an ante-room (antesacristía) into the Sacristy (18th cent.), containing a crucifix by Montañés (p. 61) and an Annunciation and a Conception (a sculpture) by Al. Cano.

A handsome portal leads from the right transept into the late-Gothic *Capilla Real, the burial-chapel of the ‘Catholic Kings’, where Charles V. caused his parents Philip of Austria and Juana the Insane also to be interred. The marble *Monuments are in the Italian early-Renaissance style: on the right those of Ferdinand and Isabella, by the Florentine Domenico Fancelli; on the left, Philip and Juana, by Bartolomé Ordóñez. The high-altar, with the kneeling statuettes of the ‘Catholic Kings’, is by Philip Vigarní, a Burgundian; the reliefs in wood, historically interesting, represent (left) the surrender of the Alhambra keys and (right) the compulsory baptism of the Moors. Behind the reliquary altars, which are opened on four festival-days only, are hung Madonnas by Dierick Bouts, altar-wings by Roger van der Weyden, a Madonna and a Descent from the Cross by Memling, and other pictures. Over an altar in the right aisle is a *Winged Picture by D. Bouts.

The third great addition to the cathedral, the Sagrario, erected as a parish church in 1705–59, occupies the site of the ancient mosque, with its eleven aisles, which was used for Christian worship down to 1661.

The picturesque Placeta de la Lonja (Pl. E, 4), on the S. side of the cathedral, affords a good view of the Lonja (Exchange), built in 1518–22, which stands before the Sagrario, of the rich architecture of the Capilla Real, and of the—

Casa del Cabildo Antigua, once the seat of the Moorish university founded here after the downfall of Cordova and Seville, afterwards the residence of the ‘Catholic Kings’, and now a cloth magazine. Its fantastic exterior dates from the 18th cent.; in the interior are two interesting rooms of the Moorish period (fee 50 c.).

From the E. end of the Calle de los Reyes Católicos (p. 75) the Calle Castro y Serrano and Calle Doctor Eximio lead to the right to the Casa de los Tiros (Pl. E, 4), a building in the Moorish castellated style, dating from the 15th cent., and now owned by the Marquesa de Campotéjar. The court contains a venerable tree-like vine. Tickets for the Generalife (comp. p. 74) are issued here.

The Calle de Santa Escolástica leads hence to the Plaza de Santo Domingo (Pl. F, 4) and the old monastery of Santo Domingo (now a military school), with its pleasing church (15–17th cent.).—A little to the S.W. is the—

Cuarto Real de Santa Domingo (Pl. F, 4; admittance seldom granted), the Al-Majarra of the Moors, now named after a tower of the 13th cent., a superb villa with a Moorish portal and a hall whose charming decoration is older than the Alhambra. The beautiful garden is said to have been laid out in Moorish times.

We now cross the Plaza Bailén to the N.W. to the favourite winter promenade (p. 74), the Carrera del Genil (Pl. E-G, 5), shaded with plane-trees, which begins at the Puerta Real (p. 75) and now comprises the former Alameda. Adjoining the Carrera on the left is the—

*Paseo del Salón (Pl. G, 5, 4). planted with elms and adorned with a bronze statue of Isabella the Catholic. Delightful view to the N.E. of Monte Mauror with the Torres Bermejas (p. 80); to the S.E. towers the majestic Sierra Nevada, from whose rocky crest the Picacho de la Veleta (11,148 ft.), the grandest point of view in all Andalusia, alone rises conspicuously.