CHAPTER THE TWENTIETH.

“Pray; madame,” I groaned, “if you have anything worse in store, bring it

on quickly for we have not committed a crime so heinous as to merit death

by torture.” The maid, whose name was Psyche, quickly spread a blanket

upon the floor (and) sought to secure an erection by fondling my member,

which was already a thousand times colder than death. Ascyltos, well aware

by now of the danger of dipping into the secrets of others, covered his

head with his mantle. (In the meantime,) the maid took two ribbons from

her bosom and bound our feet with one and our hands with the other.

(Finding myself trussed up in this fashion, I remarked, “You will not be

able to cure your mistress’ ague in this manner!” “Granted,” the maid

replied, “but I have other and surer remedies at hand,” she brought me a

vessel full of satyrion, as she said this, and so cheerfully did she

gossip about its virtues that I drank down nearly all of the liquor, and

because Ascyltos had but a moment before rejected her advances, she

sprinkled the dregs upon his back, without his knowing it.) When this

repartee had drawn to a close, Ascyltos exclaimed, “Don’t I deserve a

drink?” Given away by my laughter, the maid clapped her hands and cried,

“I put one by you, young man; did you drink so much all by yourself?”

“What’s that you say?”, Quartilla chimed in. “Did Encolpius drink all the

satyrion there was in the house?” And she laughed delightfully until her

sides shook. Finally not even Giton himself could resist a smile,

especially when the little girl caught him around the neck and showered

innumerable kisses upon him, and he not at all averse to it.

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-FIRST.

We would have cried aloud in our misery but there was no one to give us

any help, and whenever I attempted to shout, “Help! all honest citizens,”

Psyche would prick my cheeks with her hairpin, and the little girl would

intimidate Ascyltos with a brush dipped in satyrion. Then a catamite

appeared, clad in a myrtle-colored frieze robe, and girded round with a

belt. One minute he nearly gored us to death with his writhing buttocks,

and the next, he befouled us so with his stinking kisses that Quartilla,

with her robe tucked high, held up her whalebone wand and ordered him to

give the unhappy wretches quarter. Both of us then took a most solemn oath

that so dread a secret should perish with us. Several wrestling

instructors appeared and refreshed us, worn out as we were, by a massage

with pure oil, and when our fatigue had abated, we again donned our dining

clothes and were escorted to the next room, in which were placed three

couches, and where all the essentials necessary to a splendid banquet were

laid out in all their richness. We took our places, as requested, and

began with a wonderful first course. We were all but submerged in

Falernian wine. When several other courses had followed, and we were

endeavoring to keep awake Quartilla exclaimed, “How dare you think of

going to sleep when you know that the vigil of Priapus is to be kept?”

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-SECOND.

Worn out by all his troubles, Ascyltos commenced to nod, and the maid,

whom he had slighted, and of course insulted, smeared lampblack all over

his face, and painted his lips and shoulders with vermillion, while he

drowsed. Completely exhausted by so many untoward adventures, I, too, was

enjoying the shortest of naps, the whole household, within and without,

was doing the same, some were lying here and there asleep at our feet,

others leaned against the walls, and some even slept head to head upon the

threshold itself; the lamps, failing because of a lack of oil, shed a

feeble and flickering light, when two Syrians, bent upon stealing an

amphora of wine, entered the dining-room. While they were greedily pawing

among the silver, they pulled the amphora in two, upsetting the table with

all the silver plate, and a cup, which had flown pretty high, cut the head

of the maid, who was drowsing upon a couch. She screamed at that, thereby

betraying the thieves and wakening some of the drunkards. The Syrians, who

had come for plunder, seeing that they were about to be detected, were so

quick to throw themselves down besides a couch and commence to snore as if

they had been asleep for a long time, that you would have thought they

belonged there. The butler had gotten up and poured oil in the flickering

lamps by this time, and the boys, having rubbed their eyes open, had

returned to their duty, when in came a female cymbal player and the

crashing brass awoke everybody.

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-THIRD.

The banquet began all over again, and Quartilla challenged us to a drinking-bout, the crash of the cymbals lending ardor to her revel. A catamite appeared, the stalest of all mankind, well worthy of that house. Heaving a sigh, he wrung his hands until the joints cracked, and spouted out the following verses,

"Hither, hither quickly gather, pathic companions boon;

Artfully stretch forth your limbs and on with the dance and play!

Twinkling feet and supple thighs and agile buttocks in tune,

Hands well skilled in raising passions, Delian eunuchs gay!”

When he had finished his poetry, he slobbered a most evil-smelling kiss

upon me, and then, climbing upon my couch, he proceeded with all his might

and main to pull all of my clothing off. I resisted to the limit of my

strength. He manipulated my member for a long time, but all in vain. Gummy

streams poured down his sweating forehead, and there was so much chalk in

the wrinkles of his cheeks that you might have mistaken his face for a

roofless wall, from which the plaster was crumbling in a rain.

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-FOURTH.

Driven to the last extremity, I could no longer keep back the tears.

“Madame,” I burst out, “is this the night-cap which you ordered served to

me?” Clapping her hands softly she cried out, “Oh you witty rogue, you are

a fountain of repartee, but you never knew before that a catamite was

called a k-night-cap, now did you?” Then, fearing my companion would come

off better than I, “Madame,” I said, “I leave it to your sense of

fairness: is Ascyltos to be the only one in this dining-room who keeps

holiday?” “Fair enough,” conceded Quartilla, “let Ascyltos have his

k-night-cap too!” On hearing that, the catamite changed mounts, and,

having bestridden my comrade, nearly drove him to distraction with his

buttocks and his kisses. Giton was standing between us and splitting his

sides with laughter when Quartilla noticed him, and actuated by the

liveliest curiosity, she asked whose boy he was, and upon my answering

that he was my “brother,” “Why has he not kissed me then?” she demanded.

Calling him to her, she pressed a kiss upon his mouth, then putting her

hand beneath his robe, she took hold of his little member, as yet so

undeveloped. “This,” she remarked, “shall serve me very well tomorrow, as

a whet to my appetite, but today I’ll take no common fare after choice

fish!”

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-FIFTH.

She was still talking when Psyche, who was giggling, came to her side and

whispered something in her ear. What it was, I did not catch. “By all

means,” ejaculated Quartilla, “a brilliant idea! Why shouldn’t our pretty

little Pannychis lose her maidenhead when the opportunity is so

favorable?” A little girl, pretty enough, too, was led in at once; she

looked to be not over seven years of age, and she was the same one who had

before accompanied Quartilla to our room. Amidst universal applause, and

in response to the demands of all, they made ready to perform the nuptial

rites. I was completely out of countenance, and insisted that such a

modest boy as Giton was entirely unfitted for such a wanton part, and

moreover, that the child was not of an age at which she could receive that

which a woman must take. “Is that so,” Quartilla scoffed, “is she any

younger than I was, when I submitted to my first man? Juno, my patroness,

curse me if I can remember the time when I ever was a virgin, for I

diverted myself with others of my own age, as a child then as the years

passed, I played with bigger boys, until at last I reached my present age.

I suppose that this explains the origin of the proverb, ‘Who carried the

calf may carry the bull,’ as they say.” As I feared that Giton might run

greater risk if I were absent, I got up to take part in the ceremony.

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-SIXTH.

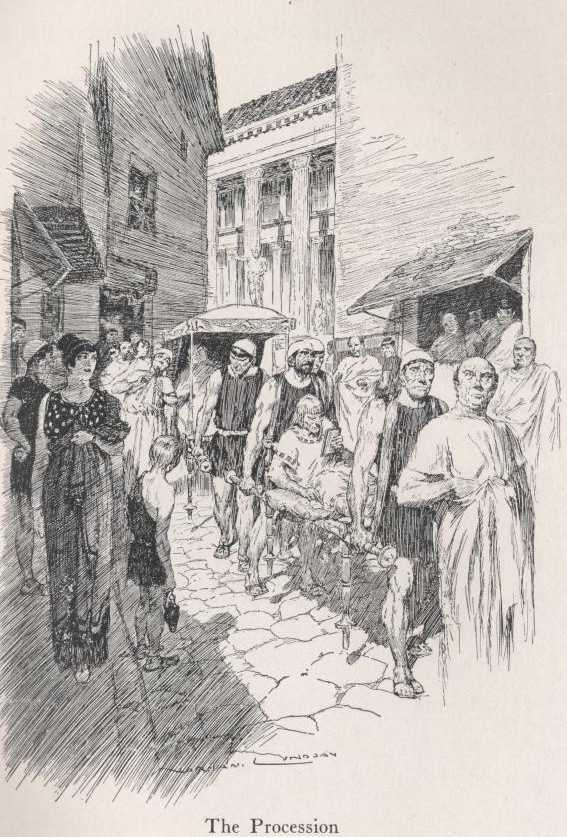

Psyche had already enveloped the child’s head in the bridal-veil, the

catamite, holding a torch, led the long procession of drunken women which

followed; they were clapping their hands, having previously decked out the

bridal-bed with a suggestive drapery. Quartilla, spurred on by the

wantonness of the others, seized hold of Giton and drew him into the

bridal-chamber. There was no doubt of the boy’s perfect willingness to go,

nor was the girl at all alarmed at the name of marriage. When they were

finally in bed, and the door shut, we seated ourselves outside the door of

the bridal-chamber, and Quartilla applied a curious eye to a chink,

purposely made, watching their childish dalliance with lascivious

attention. She then drew me gently over to her side that I might share the

spectacle with her, and when we both attempted to peep our faces were

pressed against each other; whenever she was not engrossed in the

performance, she screwed up her lips to meet mine, and pecked at me

continually with furtive kisses. [A thunderous hammering was heard at the

door, while all this was going on, and everyone wondered what this

unexpected interruption could mean, when we saw a soldier, one of the

night-watch, enter with a drawn sword in his hand, and surrounded by a

crowd of young rowdies. He glared about him with savage eyes and

blustering mien, and, catching sight of Quartilla, presently, “What’s up

now, you shameless woman,” he bawled; “what do you mean by making game of

me with lying promises, and cheating me out of the night you promised me?

But you won’t get off unpunished! You and that lover of yours are going to

find out that I’m a man!” At the soldier’s orders, his companion bound

Quartilla and myself together, mouth to mouth, breast to breast, and thigh

to thigh; and not without a great deal of laughter. Then the catamite,

also at the soldier’s order, began to beslaver me all over with the fetid

kisses of his stinking mouth, a treatment I could neither fly from, nor in

any other way avoid. Finally, he ravished me, and worked his entire

pleasure upon me. In the meantime, the satyrion which I had drunk only a

little while before spurred every nerve to lust and I began to gore

Quartilla impetuously, and she, burning with the same passion,

reciprocated in the game. The rowdies laughed themselves sick, so moved

were they by that ludicrous scene, for here was I, mounted by the stalest

of catamites, involuntarily and almost unconsciously responding with as

rapid a cadence to him as Quartilla did in her wriggling under me. While

this was going on, Pannychis, unaccustomed at her tender years to the

pastime of Venus, raised an outcry and attracted the attention of the

soldier, by this unexpected howl of consternation, for this slip of a girl

was being ravished, and Giton the victor, had won a not bloodless victory.

Aroused by what he saw, the soldier rushed upon them, seizing Pannychis,

then Giton, then both of them together, in a crushing embrace. The virgin

burst into tears and plead with him to remember her age, but her prayers

availed her nothing, the soldier only being fired the more by her childish

charms.

Pannychis covered her head at last, resolved to endure whatever the Fates

had in store for her. At this instant, an old woman, the very same who had

tricked me on that day when I was hunting for our lodging, came to the aid

of Pannychis, as though she had dropped from the clouds. With loud cries,

she rushed into the house, swearing that a gang of footpads was prowling

about the neighborhood and the people invoked the help of “All honest

men,” in vain, for the members of the night-watch were either asleep or

intent upon some carouse, as they were nowhere to be found. Greatly

terrified at this, the soldier rushed headlong from Quartilla’s house. His

companions followed after him, freeing Pannychis from impending danger and

relieving the rest of us from our fear.] (I was so weary of Quartilla’s

lechery that I began to meditate means of escape. I made my intentions

known to Ascyltos, who, as he wished to rid himself of the importunities

of Psyche, was delighted; had not Giton been shut up in the

bridal-chamber, the plan would have presented no difficulties, but we

wished to take him with us, and out of the way of the viciousness of these

prostitutes. We were anxiously engaged in debating this very point, when

Pannychis fell out of bed, and dragged Giton after her, by her own weight.

He was not hurt, but the girl gave her head a slight bump, and raised such

a clamor that Quartilla, in a terrible fright, rushed headlong into the

room, giving us the opportunity of making off. We did not tarry, but flew

back to our inn where,) throwing ourselves upon the bed, we passed the

remainder of the night without fear. (Sallying forth next day, we came

upon two of our kidnappers, one of whom Ascyltos savagely attacked the

moment he set eyes upon him, and, after having thrashed and seriously

wounded him, he ran to my aid against the other. He defended himself so

stoutly, however, that he wounded us both, slightly, and escaped

unscathed.) The third day had now dawned, the date set for the free dinner

(at Trimalchio’s,) but battered as we were, flight seemed more to our

taste than quiet, so (we hastened to our inn and, as our wounds turned out

to be trifling, we dressed them with vinegar and oil, and went to bed. The

ruffian whom we had done for, was still lying upon the ground and we

feared detection.) Affairs were at this pass, and we were framing

melancholy excuses with which to evade the coming revel, when a slave of

Agamemnon’s burst in upon our trembling conclave and said, “Don’t you know

with whom your engagement is today? The exquisite Trimalchio, who keeps a

clock and a liveried bugler in his dining-room, so that he can tell,

instantly, how much of his life has run out!” Forgetting all our troubles

at that, we dressed hurriedly and ordered Giton, who had very willingly

performed his servile office, to follow us to the bath.

VOLUME II.

THE DINNER OF TRIMALCHIO

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-SEVENTH.

Having put on our clothes, in the meantime, we commenced to stroll around

and soon, the better to amuse ourselves, approached the circle of players;

all of a sudden we caught sight of a bald-headed old fellow, rigged out in

a russet colored tunic, playing ball with some long haired boys. It was

not so much the boys who attracted our attention, although they might well

have merited it, as it was the spectacle afforded by this beslippered

paterfamilias playing with a green ball. If one but touched the ground, he

never stooped for it to put it back in play; for a slave stood by with a

bagful from which the players were supplied. We noted other innovations as

well, for two eunuchs were stationed at opposite sides of the ring, one of

whom held a silver chamber-pot, the other counted the balls; not those

which bounced back and forth from hand to hand, in play, but those which

fell to the ground. While we were marveling at this display of refinement,

Menelaus rushed up, “He is the one with whom you will rest upon your

elbow,” he panted, “what you see now, is only a prelude to the dinner.”

Menelaus had scarcely ceased speaking when Trimalchio snapped his fingers;

the eunuch, hearing the signal, held the chamber-pot for him while he

still continued playing. After relieving his bladder, he called for water

to wash his hands, barely moistened his fingers, and dried them upon a

boy’s head.

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-EIGHTH.

To go into details would take too long. We entered the bath, finally, and after sweating for a minute or two in the warm room, we passed through into the cold water. But short as was the time, Trimalchio had already been sprinkled with perfume and was being rubbed down, not with linen towels, however, but with cloths made from the finest wool. Meanwhile, three masseurs were guzzling Falernian under his eyes, and when they spilled a great deal of it in their brawling, Trimalchio declared they were pouring a libation to his Genius. He was then wrapped in a coarse scarlet wrap-rascal, and placed in a litter. Four runners, whose liveries were decorated with metal plates, preceded him, as also did a wheel-chair in which rode his favorite, a withered, blear eyed slave, even more repulsive looking than his master. A singing boy approached the head of his litter, as he was being carried along, and played upon small pipes the whole way, just as if he were communicating some secret to his master’s ear. Marveling greatly, we followed, and met Agamemnon at the outer door, to the post of which was fastened a small tablet bearing this inscription:

NO SLAVE TO LEAVE THE PREMISES

WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE MASTER.

PENALTY ONE HUNDRED LASHES.

In the vestibule stood the porter, clad in green and girded with a

cherry-colored belt, shelling peas into a silver dish. Above the threshold

was suspended a golden cage, from which a black and white magpie greeted

the visitors.

CHAPTER THE TWENTY-NINTH.

I almost fell backwards and broke my legs while staring at all this, for to the left, as we entered, not far from the porter’s alcove, an enormous dog upon a chain was painted upon the wall, and above him this inscription, in capitals:

BEWARE THE DOG.

My companions laughed, but I plucked up my courage and did not hesitate,

but went on and examined the entire wall. There was a scene in a slave

market, the tablets hanging from the slaves’ necks, and Trimalchio

himself, wearing his hair long, holding a caduceus in his hand, entering

Rome, led by the hand of Minerva. Then again the painstaking artist had

depicted him casting up accounts, and still again, being appointed

steward; everything being explained by inscriptions. Where the walls gave

way to the portico, Mercury was shown lifting him up by the chin, to a

tribunal placed on high. Near by stood Fortune with her horn of plenty,

and the three Fates, spinning golden flax. I also took note of a group of

runners, in the portico, taking their exercise under the eye of an

instructor, and in one corner was a large cabinet, in which was a very

small shrine containing silver Lares, a marble Venus, and a golden casket

by no means small, which held, so they told us, the first shavings of

Trimalchio’s beard. I asked the hall-porter what pictures were in the

middle hall. “The Iliad and the Odyssey,” he replied, “and the

gladiatorial games given under Laenas.” There was no time in which to

examine them all.

CHAPTER THE THIRTIETH.

We had now come to the dining-room, at the entrance to which sat a factor, receiving accounts, and, what gave me cause for astonishment, rods and axes were fixed to the door-posts, superimposed, as it were, upon the bronze beak of a ship, whereon was inscribed:

TO GAIUS POMPEIUS TRIMALCHIO

AUGUSTAL, SEVIR

FROM CINNAMUS HIS

STEWARD.

A double lamp, suspended from the ceiling, hung beneath the inscription, and a tablet was fixed to each door-post; one, if my memory serves me, was inscribed,

ON DECEMBER THIRTIETH AND

THIRTY FIRST

OUR

GAIUS DINES OUT

the other bore a painting of the moon in her phases, and the seven

planets, and the days which were lucky and those which were unlucky,

distinguished by distinctive studs. We had had enough of these novelties

and started to enter the dining-room when a slave, detailed to this duty,

cried out, “Right foot first.” Naturally, we were afraid that some of us

might break some rule of conduct and cross the threshold the wrong way;

nevertheless, we started out, stepping off together with the right foot,

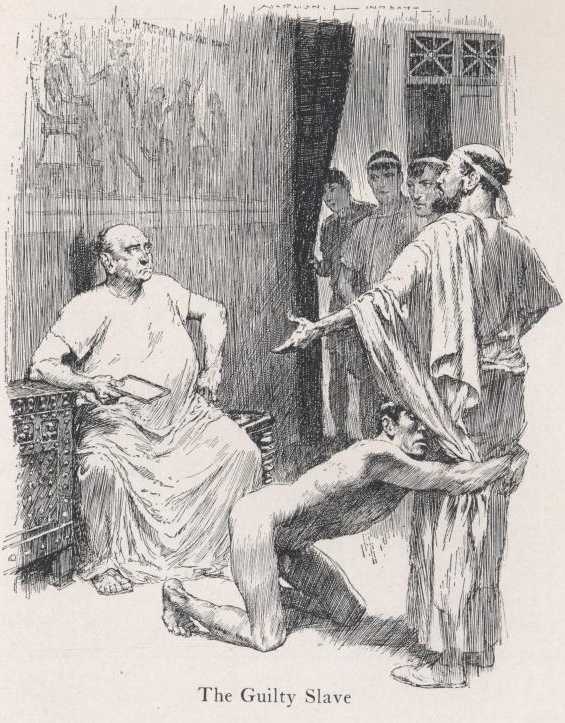

when all of a sudden, a slave who had been stripped, threw himself at our

feet, and commenced begging us to save him from punishment, as it was no

serious offense for which he was in jeopardy; the steward’s clothing had

been stolen from him in the baths, and the whole value could scarcely

amount to ten sesterces. So we drew back our right feet and intervened

with the steward, who was counting gold pieces in the hall, begging him to

remit the slave’s punishment. Putting a haughty face on the matter, “It’s

not the loss I mind so much,” he said, “as it is the carelessness of this

worthless rascal. He lost my dinner clothes, given me on my birthday they

were, by a certain client, Tyrian purple too, but it had been washed once

already. But what does it amount to? I make you a present of the

scoundrel!”

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-FIRST.

We felt deeply obligated by his great condescension, and the same slave for whom we had interceded, rushed up to us as we entered the dining-room, and to our astonishment, kissed us thick and fast, voicing his thanks for our kindness. “You’ll know in a minute whom you did a favor for,” he confided, “the master’s wine is the thanks of a grateful butler!” At length we reclined, and slave boys from Alexandria poured water cooled with snow upon our hands, while others following, attended to our feet and removed the hangnails with wonderful dexterity, nor were they silent even during this disagreeable operation, but they all kept singing at their work. I was desirous of finding out whether the whole household could sing, so I ordered a drink; a boy near at hand instantly repeated my order in a singsong voice fully as shrill, and whichever one you accosted did the same. You would not imagine that this was the dining-room of a private gentleman, but rather that it was an exhibition of pantomimes. A very inviting relish was brought on, for by now all the couches were occupied save only that of Trimalchio, for whom, after a new custom, the chief place was reserved.

On the tray stood a donkey made of Corinthian bronze, bearing panniers

containing olives, white in one and black in the other. Two platters

flanked the figure, on the margins of which were engraved Trimalchio’s

name and the weight of the silver in each. Dormice sprinkled with

poppy-seed and honey were served on little bridges soldered fast to the

platter, and hot sausages on a silver gridiron, underneath which were

damson plums and pomegranate seeds.

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-SECOND.

We were in the midst of these delicacies when, to the sound of music,

Trimalchio himself was carried in and bolstered up in a nest of small

cushions, which forced a snicker from the less wary. A shaven poll

protruded from a scarlet mantle, and around his neck, already muffled with

heavy clothing, he had tucked a napkin having a broad purple stripe and a

fringe that hung down all around. On the little finger of his left hand he

wore a massive gilt ring, and on the first joint of the next finger, a

smaller one which seemed to me to be of pure gold, but as a matter of fact

it had iron stars soldered on all around it. And then, for fear all of his

finery would not be displayed, he bared his right arm, adorned with a

golden arm-band and an ivory circlet clasped with a plate of shining

metal.

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-THIRD.

Picking his teeth with a silver quill, “Friends,” said he, “it was not

convenient for me to come into the dining-room just yet, but for fear my

absence should cause you any inconvenience, I gave over my own pleasure:

permit me, however, to finish my game.” A slave followed with a terebinth

table and crystal dice, and I noted one piece of luxury that was

superlative; for instead of black and white pieces, he used gold and

silver coins. He kept up a continual flow of various coarse expressions.

We were still dallying with the relishes when a tray was brought in, on

which was a basket containing a wooden hen with her wings rounded and

spread out as if she were brooding. Two slaves instantly approached, and

to the accompaniment of music, commenced to feel around in the straw. They

pulled out some pea-hen’s eggs, which they distributed among the diners.

Turning his head, Trimalchio saw what was going on. “Friends,” he

remarked. “I ordered pea-hen’s eggs set under the hen, but I’m afraid

they’re addled, by Hercules I am let’s try them anyhow, and see if they’re

still fit to suck.” We picked up our spoons, each of which weighed not

less than half a pound, and punctured the shells, which were made of flour

and dough, and as a matter of fact, I very nearly threw mine away for it

seemed to me that a chick had formed already, but upon hearing an old

experienced guest vow, “There must be something good here,” I broke open

the shell with my hand and discovered a fine fat fig-pecker, imbedded in a

yolk seasoned with pepper.

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-FOURTH.

Having finished his game, Trimalchio was served with a helping of everything and was announcing in a loud voice his willingness to join anyone in a second cup of honied wine, when, to a flourish of music, the relishes were suddenly whisked away by a singing chorus, but a small dish happened to fall to the floor, in the scurry, and a slave picked it up. Seeing this, Trimalchio ordered that the boy be punished by a box on the ear, and made him throw it down again; a janitor followed with his broom and swept the silver dish away among the litter. Next followed two long-haired Ethiopians, carrying small leather bottles, such as are commonly seen in the hands of those who sprinkle sand in the arena, and poured wine upon our hands, for no one offered us water. When complimented upon these elegant extras, the host cried out, “Mars loves a fair fight: and so I ordered each one a separate table: that way these stinking slaves won’t make us so hot with their crowding.” Some glass bottles carefully sealed with gypsum were brought in at that instant; a label bearing this inscription was fastened to the neck of each one:

OPIMIAN FALERNIAN

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OLD.

While we were studying the labels, Trimalchio clapped his hands and cried, “Ah me! To think that wine lives longer than poor little man. Let’s fill ‘em up! There’s life in wine and this is the real Opimian, you can take my word for that. I offered no such vintage yesterday, though my guests were far more respectable.” We were tippling away and extolling all these elegant devices, when a slave brought in a silver skeleton, so contrived that the joints and movable vertebra could be turned in any direction. He threw it down upon the table a time or two, and its mobile articulation caused it to assume grotesque attitudes, whereupon Trimalchio chimed in:

“Poor man is nothing in the scheme of things

And Orcus grips us and to Hades flings

Our bones! This skeleton before us here

Is as important as we ever were!

Let’s live then while we may and life is dear.”

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-FIFTH.

The applause was followed by a course which, by its oddity, drew every

eye, but it did not come up to our expectations. There was a circular tray

around which were displayed the signs of the zodiac, and upon each sign

the caterer had placed the food best in keeping with it. Ram’s vetches on

Aries, a piece of beef on Taurus, kidneys and lamb’s fry on Gemini, a

crown on Cancer, the womb of an unfarrowed sow on Virgo, an African fig on

Leo, on Libra a balance, one pan of which held a tart and the other a

cake, a small seafish on Scorpio, a bull’s eye on Sagittarius, a sea

lobster on Capricornus, a goose on Aquarius and two mullets on Pisces. In

the middle lay a piece of cut sod upon which rested a honeycomb with the

grass arranged around it. An Egyptian slave passed bread around from a

silver oven and in a most discordant voice twisted out a song in the

manner of the mime in the musical farce called Laserpitium. Seeing that we

were rather depressed at the prospect of busying ourselves with such vile

fare, Trimalchio urged us to fall to: “Let us fall to, gentlemen, I beg of

you, this is only the sauce!”

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-SIXTH.

While he was speaking, four dancers ran in to the time of the music, and

removed the upper part of the tray. Beneath, on what seemed to be another

tray, we caught sight of stuffed capons and sows’ bellies, and in the

middle, a hare equipped with wings to resemble Pegasus. At the corners of

the tray we also noted four figures of Marsyas and from their bladders

spouted a highly spiced sauce upon fish which were swimming about as if in

a tide-race. All of us echoed the applause which was started by the

servants, and fell to upon these exquisite delicacies, with a laugh.

“Carver,” cried Trimalchio, no less delighted with the artifice practised

upon us, and the carver appeared immediately. Timing his strokes to the

beat of the music he cut up the meat in such a fashion as to lead you to

think that a gladiator was fighting from a chariot to the accompaniment of

a water-organ. Every now and then Trimalchio would repeat “Carver,

Carver,” in a low voice, until I finally came to the conclusion that some

joke was meant in repeating a word so frequently, so I did not scruple to

question him who reclined above me. As he had often experienced byplay of

this sort he explained, “You see that fellow who is carving the meat,

don’t you? Well, his name is Carver. Whenever Trimalchio says Carver,

carve her, by the same word, he both calls and commands!”

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-SEVENTH.

I could eat no more, so I turned to my whilom informant to learn as much

as I could and sought to draw him out with far-fetched gossip. I inquired

who that woman could be who was scurrying about hither and yon in such a

fashion. “She’s called Fortunata,” he replied. “She’s the wife of

Trimalchio, and she measures her money by the peck. And only a little

while ago, what was she! May your genius pardon me, but you would not have

been willing to take a crust of bread from her hand. Now, without rhyme or

reason, she’s in the seventh heaven and is Trimalchio’s factotum, so much

so that he would believe her if she told him it was dark when it was broad

daylight! As for him, he don’t know how rich he is, but this harlot keeps

an eye on everything and where you least expect to find her, you’re sure

to run into her. She’s temperate, sober, full of good advice, and has many

good qualities, but she has a scolding tongue, a very magpie on a sofa,

those she likes, she likes, but those she dislikes, she dislikes!

Trimalchio himself has estates as broad as the flight of a kite is long,

and piles of money. There’s more silver plate lying in his steward’s

office than other men have in their whole fortunes! And as for slaves,

damn me if I believe a tenth of them knows the master by sight. The truth

is, that these stand-a-gapes are so much in awe of him that any one of

them would step into a fresh dunghill without ever knowing it, at a mere

nod from him!”

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-EIGHTH.

“And don’t you get the idea that he buys anything; everything is produced at home, wool, pitch, pepper, if you asked for hen’s milk you would get it. Because he wanted his wool to rival other things in quality, he bought rams at Tarentum and sent ‘em into his flocks with a slap on the arse. He had bees brought from Attica, so he could produce Attic honey at home, and, as a side issue, so he could improve the native bees by crossing with the Greek. He even wrote to India for mushroom seed one day, and he hasn’t a single mule that wasn’t sired by a wild ass. Do you see all those cushions? Not a single one but what is stuffed with either purple or scarlet wool! He hasn’t anything to worry about! Look out how you criticise those other fellow-freedmen-friends of his, they’re all well heeled. See the fellow reclining at the bottom of the end couch? He’s worth his 800,000 any day, and he rose from nothing. Only a short while ago he had to carry faggots on his own back. I don’t know how true it is, but they say that he snatched off an Incubo’s hat and found a treasure! For my part, I don’t envy any man anything that was given him by a god. He still carries the marks of his box on the ear, and he isn’t wishing himself any bad luck! He posted this notice, only the other day:

CAIUS POMPONIUS DIOGENES HAS

PURCHASED A HOUSE

THIS GARRET FOR RENT AFTER

THE KALENDS OF JULY.

“What do you think of the fellow in the freedman’s place? He has a good front, too, hasn’t he? And he has a right to. He saw his fortune multiplied tenfold, but he lost heavily through speculation at the last. I don’t think he can call his very hair his own, and it is no fault of his either, by Hercules, it isn’t. There’s no better fellow anywhere; his rascally freedmen cheated him out of everything. You know very well how it is; everybody’s business is nobody’s business, and once let business affairs start to go wrong, your friends will stand from under! Look at the fix he’s in, and think what a fine trade he had! He used to be an undertaker. He dined like a king, boars roasted whole in their shaggy Bides, bakers’ pastries, birds, cooks and bakers! More wine was spilled under his table than another has in his wine cellar. His life was like a pipe dream, not like an ordinary mortal’s. When his affairs commenced to go wrong, and he was afraid his creditors would guess that he was bankrupt, he advertised an auction and this was his placard:

JULIUS PROCULUS WILL SELL AT

AUCTION HIS SUPERFLUOUS

FURNITURE”

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-NINTH.

Trimalchio broke in upon this entertaining gossip, for the course had been

removed and the guests, happy with wine, had started a general

conversation: lying back upon his couch, “You ought to make this wine go

down pleasantly,” he said, “the fish must have something to swim in. But I

say, you didn’t think I’d be satisfied with any such dinner as you saw on

the top of that tray? ‘Is Ulysses no better known?’ Well, well, we

shouldn’t forget our culture, even at dinner. May the bones of my patron

rest in peace, he wanted me to become a man among men. No one can show me

anything new, and that little tray has proved it. This heaven where the

gods live, turns into as many different signs, and sometimes into the Ram:

therefore, whoever is born under that sign will own many flocks and much

wool, a hard head, a shameless brow, and a sharp horn. A great many

school-teachers and rambunctious butters-in are born under that sign.” We

applauded the wonderful penetration of our astrologer and he ran on, “Then

the whole heaven turns into a bull-calf and the kickers and herdsmen and

those who see to it that their own bellies are full, come into the world.

Teams of horses and oxen are born under the Twins, and well-hung wenchers

and those who bedung both sides of the wall. I was born under the Crab and

therefore stand on many legs and own much property on land and sea, for

the crab is as much at home on one as he is in the other. For that reason,

I put nothing on that sign for fear of weighing down my own destiny.

Bulldozers and gluttons are born under the Lion, and women and fugitives

and chain-gangs are born under the Virgin. Butchers and perfumers are born

under the Balance, and all who think that it is their business to

straighten things out. Poisoners and assassins are born under the

Scorpion. Cross-eyed people who look at the vegetables and sneak away with

the bacon, are born under the Archer. Horny-handed sons of toil are born

under Capricorn. Bartenders and pumpkin-heads are born under the

Water-Carrier. Caterers and rhetoricians are born under the Fishes: and so

the world turns round, just like a mill, and something bad always comes to

the top, and men are either being born or else they’re dying. As to the

sod and the honeycomb in the middle, for I never do anything without a

reason, Mother Earth is in the centre, round as an egg, and all that is

good is found in her, just like it is in a honeycomb.”

CHAPTER THE FORTIETH.

“Bravo!” we yelled, and, with hands uplifted to the ceiling, we swore that

such fellows as Hipparchus and Aratus were not to be compared with him. At

length some slaves came in who spread upon the couches some coverlets upon

which were embroidered nets and hunters stalking their game with

boar-spears, and all the paraphernalia of the chase. We knew not what to

look for next, until a hideous uproar commenced, just outside the

dining-room door, and some Spartan hounds commenced to run around the

table all of a sudden. A tray followed them, upon which was served a wild

boar of immense size, wearing a liberty cap upon its head, and from its

tusks hung two little baskets of woven palm fibre, one of which contained

Syrian dates, the other, Theban. Around it hung little suckling pigs made

from pastry, signifying that this was a brood-sow with her pigs at suck.

It turned out that these were souvenirs intended to be taken home. When it

came to carving the boar, our old friend Carver, who had carved the

capons, did not appear, but in his place a great bearded giant, with bands

around his legs, and wearing a short hunting cape in which a design was

woven. Drawing his hunting- knife, he plunged it fiercely into the boar’s

side, and some thrushes flew out of the gash. fowlers, ready with their

rods, caught them in a moment, as they fluttered around the room and

Trimalchio ordered one to each guest, remarking, “Notice what fine acorns

this forest-bred boar fed on,” and as he spoke, some slaves removed the

little baskets from the tusks and divided the Syrian and Theban dates

equally among the diners.

CHAPTER THE FORTY-FIRST.

Getting a moment to myself, in the meantime, I began to speculate as to

why the boar had come with a liberty cap upon his head. After exhausting

my invention with a thousand foolish guesses, I made bold to put the

riddle which teased me to my old informant. “Why, sure,” he replied, “even

your slave could explain that; there’s no riddle, everything’s as plain as

day! This boar made his first bow as the last course of yesterday’s dinner

and was dismissed by the guests, so today he comes back as a freedman!” I

damned my stupidity and refrained from asking any more questions for fear

I might leave the impression that I had never dined among decent people

before. While we were speaking, a handsome boy, crowned with vine leaves

and ivy, passed grapes around, in a little basket, and impersonated

Bacchus-happy, Bacchus-drunk, and Bacchus-dreaming, reciting, in the

meantime, his master’s verses, in a shrill voice. Trimalchio turned to him

and said, “Dionisus, be thou Liber,” whereupon the boy immediately

snatched the cap from the boar’s head, and put it upon his own. At that

Trimalchio added, “You can’t deny that my father’s middle name was Liber!”

We applauded Trimalchio’s conceit heartily, and kissed the boy as he went

around. Trimalchio retired to the close-stool, after this course, and we,

having freedom of action with the tyrant away, began to draw the other

guests out. After calling for a bowl of wine, Dama spoke up, “A day’s

nothing at all: it’s night before you can turn around, so you can’t do

better than to go right to the dining-room from your bed. It’s been so

cold that I can hardly get warm in a bath, but a hot drink’s as good as an

overcoat: I’ve had some long pegs, and between you and me, I’m a bit

groggy; the booze has gone to my head.”

CHAPTER THE FORTY-SECOND.

Here Seleucus took up the tale. “I don’t bathe every day,” he confided, “a

bath uses you up like a fuller: water’s got teeth and your strength wastes

away a little every day; but when I’ve downed a pot of mead, I tell the

cold to suck my cock! I couldn’t bathe today anyway, because I was at a

funeral; dandy fellow, he was too, good old Chrysanthus slipped his wind!

Why, only the other day he said good morning’ to me, and I almost think

I’m talking to him now! Gawd’s truth, we’re only blown-up bladders

strutting around, we’re less than flies, for they have some good in them,

but we’re only bubbles. And supposing he had not kept to such a low diet!

Why, not a drop of water or a crumb of bread so much as passed his lips

for five days; and yet he joined the majority! Too many doctors did away

with him, or rather, his time had come, for a doctor’s not good for

anything except for a consolation to your mind! He was well carried out,

anyhow, in the very bed he slept in during his lifetime. And he was

covered with a splendid pall: the mourning was tastefully managed; he had

freed some slaves; even though his wife was sparing with her tears: and

what if he hadn’t treated her so well! But when you come to women, women

all belong to the kite species: no one ought to waste a good turn upon one

of them; it’s just like throwing it down a well! An old love’s like a

cancer!”

CHAPTER THE FORTY-THIRD.

He was becoming very tiresome, and Phileros cried out, “Let’s think about

the living! He has what was coming to him, he lived respectably, and

respectably he died. What’s he got to kick about’? He made his pile from

an as, and would pick a quadrans out of a dunghill with his teeth, any old

time. And he grew richer and richer, of course: just like a honeycomb. I

expect that he left all of a hundred thousand, by Hercules, I do! All in

cold cash, too; but I’ve eaten dog’s tongue and must speak the truth: he

was foul-mouthed, had a ready tongue, he was a trouble maker and no man.

Now his brother was a good fellow, a friend to his friend, free-handed,

and he kept a liberal table. He picked a loser at the start, but his first

vintage set him upon his legs, for he sold his wine at the figure he

demanded, and, what made him hold his head higher still, he came into a

legacy from which he stole more than had been left to him. Then that fool

friend of yours, in a fit of anger at his brother, willed his property

away to some son-of-a-bitch or other, who he was, I don’t know, but when a

man runs away from his own kin, he has a long way to go! And what’s more,

he had some slaves who were ear-specialists at the keyhole, and they did

him a lot of harm, for a man won’t prosper when he believes, on the spot,

every tale that he hears; a man in business, especially. Still, he had a

good time as long as he lived: for happy’s the fellow who gets the gift,

not the one it was meant for. He sure was Fortune’s son! Lead turned to

gold in his hands. It’s easy enough when everything squares up and runs on

schedule. How old would you think he was? Seventy and over, but he was as

tough as horn, carried his age well, and was as black as a crow. I knew

the fellow for years and years, and he was a lecher to the very last. I

don’t believe that even the dog in his house escaped his attentions, by

Hercules, I don’t; and what a boy-lover he was! Saw a virgin in every one

he met! Not that I blame him though, for it’s all he could take with him.”

CHAPTER THE FORTY-FOURTH.

Phileros had his say and Ganymedes exclaimed, “You gabble away about

things that don’t concern heaven or earth: and none of you cares how the

price of grain pinches. I couldn’t even get a mouthful of bread today, by

Hercules, I couldn’t. How the drought does hang on! We’ve had famine for a

year. If the damned AEdiles would only get what’s coming to them. They

graft with the bakers, scratch-my-arse-and-I’ll-scratch-yours! That’s the

way it always is, the poor devils are out of luck, but the jaws of the

capitalists are always keeping the Saturnalia. If only we had such

lion-hearted sports as we had when I first came from Asia! That was the

life! If the flour was not the very best, they would beat up those

belly-robbing grafters till they looked like Jupiter had been at them. How

well I remember Safinius; he lived near the old arch, when I was a boy.

For a man, he was one hot proposition! Wherever he went, the ground

smoked! But he was square, dependable, a friend to a friend, you could

safely play mora with him, in the dark. But how he did peel them in the

town hall: he spoke no parables, not he! He did everything straight from

the shoulder and his voice roared like a trumpet in the forum. He never

sweat nor spat. I don’t know, but I think he had a strain of the Asiatic

in him. And how civil and friendly-like he was, in returning everyone’s

greeting; called us all by name, just like he was one of us! And so

provisions were cheap as dirt in those days. The loaf you got for an as,

you couldn’t eat, not even if someone helped you, but you see them no

bigger than a bull’s eye now, and the hell of it is that things are

getting worse every day; this colony grows backwards like a calf’s tall!

Why do we have to put up with an AEdile here, who’s not worth three

Caunian figs and who thinks more of an as than of our lives? He has a good

time at home, and his daily income’s more than another man’s fortune. I

happen to know where he got a thousand gold pieces. If we had any nuts,

he’d not be so damned well pleased with himself! Nowadays, men are lions

at home and foxes abroad. What gets me is, that I’ve already eaten my old

clothes, and if this high cost of living keeps on, I’ll have to sell my

cottages! What’s going to happen to this town, if neither gods nor men

take pity on it? May I never have any luck if I don’t believe all this

comes from the gods! For no one believes that heaven is heaven, no one

keeps a fast, no one cares a hang about Jupiter: they all shut their eyes

and count up their own profits. In the old days, the married women, in

their stolas, climbed the hill in their bare feet, pure in heart, and with

their hair unbound, and prayed to Jupiter for rain! And it would pour down

in bucketfuls then or never, and they’d all come home, wet as drowned

rats. But the gods all have the gout now, because we are not religious;

and so our fields are burning up!”

CHAPTER THE FORTY-FIFTH.

“Don’t be so down in the mouth,” chimed in Echion, the ragman; “if it

wasn’t that it’d be something else, as the farmer said, when he lost his

spotted pig. If a thing don’t happen today, it may tomorrow. That’s the

way life jogs along. You couldn’t name a better country, by Hercules, you

couldn’t, if only the men had any brains. She’s in hot water right now,

but she ain’t the only one. We oughtn’t to be so particular; heaven’s as

far away everywhere else. If you were somewhere else, you’d swear that

pigs walked around here already roasted. Think of what’s coming! We’ll

soon have a fine gladiator show to last for three days, no training-school

pupils; most of them will be freedmen. Our Titus has a hot head and plenty

of guts and it will go to a finish. I’m well acquainted with him, and

he’ll not stand for any frame-ups. It will be cold steel in the best

style, no running away, the shambles will be in the middle of the

amphitheatre where all the crowd can see. And what’s more, he has the

coin, for he came into thirty million when his father had the bad luck to

die. He could blow in four hundred thousand and his fortune never feel it,

but his name would live forever. He has some dwarfs already, and a woman

to fight from a chariot. Then, there’s Glyco’s steward; he was caught

screwing Glyco’s wife. You’ll see some battle between jealous husbands and

favored lovers. Anyhow, that cheap screw of a Glyco condemned his steward

to the beasts and only published his own shame. How could the slave go

wrong when he only obeyed orders? It would have been better if that

she-piss- pot, for that’s all she’s fit for, had been tossed by the bull,

but a fellow has to beat the saddle when he can’t beat the jackass. How

could Glyco ever imagine that a sprig of Hermogenes’ planting could turn

out well? Why, Hermogenes could trim the claws of a flying hawk, and no

snake ever hatched out a rope yet! And look at Glyco! He’s smoked himself

out in fine shape, and as long as he lives, he’ll carry that stain! No one

but the devil himself can wipe that out, but chickens always come home to

roost. My nose tells me that Mammaea will set out a spread: two bits

apiece for me and mine! And he’ll nick Norbanus out of his political pull

if he does; you all know that it’s to his interest to hump himself to get

the best of him. And honestly, what did that fellow ever do for us? He

exhibited some two cent gladiators that were so near dead they’d have

fallen flat if you blew your breath at them. I’ve seen better thugs sent

against wild beasts! And the cavalry he killed looked about as much like

the real thing as the horsemen on the lamps; you would have taken them for

dunghill cocks! One plug had about as much action as a jackass with a

pack-saddle; another was club-footed; and a third who had to take the

place of one that was killed, was as good as dead, and hamstrung into the

bargain. There was only one that had any pep, and he was a Thracian, but

he only fought when we egged him on. The whole crowd was flogged

afterwards. How the mob did yell ‘Lay it on!’ They were nothing but

runaways. And at that he had the nerve to say, ‘I’ve given you a show.’

‘And I’ve applauded,’ I answered; ‘count it up and you’ll find that I gave

more than I got! One hand washes the other.’”

CHAPTER THE FORTY-SIXTH

“Agamemnon, your looks seem to say, What’s this boresome nut trying to

hand us?’ Well, I’m talking because you, who can talk book-foolishness,

won’t. You don’t belong to our bunch, so you laugh in your sleeve at the

way us poor people talk, but we know that you’re only a fool with a lot of

learning. Well, what of it? Some day I’ll get you to come to my country

place and take a look at my little estate. We’ll have fresh eggs and

spring chicken to chew on when we get there; it will be all right even if

the weather has kept things back this year. We’ll find enough to satisfy

us, and my kid will soon grow up to be a pupil of yours; he can divide up

to four, now, and you’ll have a little servant at your side, if he lives.

When he has a minute to himself, he never takes his eyes from his tablets;

he’s smart too, and has the right kind of stuff in him, even if he is

crazy about birds. I’ve had to kill three of his linnets already. I told

him that a weasel had gotten them, but he’s found another hobby, now he

paints all the time. He’s left the marks of his heels on his Greek

already, and is doing pretty well with his Latin, although his master’s

too easy with him; won’t make him stick to one thing. He comes to me to

get me to give him something to write when his master don’t want to work.

Then there’s another tutor, too, no scholar, but very painstaking, though;

he can teach you more than he knows himself. He comes to the house on

holidays and is always satisfied with whatever you pay him. Some little

time ago, I bought the kid some law books; I want him to have a smattering

of the law for home use. There’s bread in that! As for literature, he’s

got enough of that in him already; if he begins to kick, I’ve concluded

that I’ll make him learn some trade; the barber’s, say, or the

auctioneer’s, or even the lawyer’s. That’s one thing no one but the devil

can do him out of! ‘Believe what your daddy says, Primigenius,’ I din into

his ears every day, ‘whenever you learn a thing, it’s yours. Look at

Phileros the attorney; he’d not be keeping the wolf from the door now if

he hadn’t studied. It’s not long since he had to carry his wares on his

back and peddle them, but he can put up a front with Norbanus himself now!

Learning’s a fine thing, and a trade won’t starve.’”

CHAPTER THE FORTY-SEVENTH.

Twaddle of this sort was being bandied about when Trimalchio came in;

mopping his forehead and washing his hands in perfume, he said, after a

short pause, “Pardon me, gentlemen, but my stomach’s been on strike for

the past few days and the doctors disagreed about the cause. But

pomegranate rind and pitch steeped in vinegar have helped me, and I hope

that my belly will get on its good behavior, for sometimes there’s such a

rumbling in my guts that you’d think a bellowing bull was in there. So if

anyone wants to do his business, there’s no call to be bashful about it.

None of us was born solid! I don’t know of any worse torment than having

to hold it in, it’s the one thing Jupiter himself can’t hold in. So you’re

laughing, are you, Fortunata? Why, you’re always keeping me awake at night

yourself. I never objected yet to anyone in my dining-room relieving

himself when he wanted to, and the doctors forbid our holding it in.

Everything’s ready outside, if the call’s more serious, water,

close-stool, and anything else you’ll need. Believe me, when this rising

vapor gets to the brain, it puts the whole body on the burn. Many a one

I’ve known to kick in just because he wouldn’t own up to the truth.” We

thanked him for his kindness and consideration, and hid our laughter by

drinking more and oftener. We had not realized that, as yet, we were only

in the middle of the entertainment, with a hill still ahead, as the saying

goes. The tables were cleared off to the beat of music, and three white

hogs, muzzled, and wearing bells, were brought into the dining-room. The

announcer informed us that one was a two-year-old, another three, and the

third just turned six. I had an idea that some rope-dancers had come in

and that the hogs would perform tricks, just as they do for the crowd on

the streets, but Trimalchio dispelled this illusion by asking, “Which one

will you have served up immediately, for dinner? Any country cook can

manage a dunghill cock, a pentheus hash, or little things like that, but

my cooks are well used to serving up calves boiled whole, in their

cauldrons!” Then he ordered a cook to be called in at once, and without

awaiting our pleasure, he directed that the oldest be butchered, and

demanded in a loud voice, “What division do you belong too?” When the

fellow made answer that he was from the fortieth, “Were you bought, or

born upon my estates?” Trimalchio continued. “Neither,” replied the cook,

“I was left to you by Pansa’s will.” “See to it that this is properly

done,” Trimalchio warned, “or I’ll have you transferred to the division of

messengers!” and the cook, bearing his master’s warning in mind, departed

for the kitchen with the next course in tow.

CHAPTER THE FORTY-EIGHTH.

Trimalchio’s threatening face relaxed and he turned to us, “If the wine don’t please you,” he said, “I’ll change it; you ought to do justice to it by drinking it. I don’t have to buy it, thanks to the gods. Everything here that makes your mouths water, was produced on one of my country places which I’ve never yet seen, but they tell me it’s down Terracina and Tarentum way. I’ve got a notion to add Sicily to my other little holdings, so in case I want to go to Africa, I’ll be able to sail along my own coasts. But tell me the subject of your speech today, Agamemnon, for, though I don’t plead cases myself, I studied literature for home use, and for fear you should think I don’t care about learning, let me inform you that I have three libraries, one Greek and the others Latin. Give me the outline of your speech if you like me.”

“A poor man and a rich man were enemies,” Agamemmon began, when: “What’s a

poor man?” Trimalchio broke in. “Well put,” Agamemnon conceded and went

into details upon some problem or other, what it was I do not know.

Trimalchio instantly rendered the following verdict, “If that’s the case,

there’s nothing to dispute about; if it’s not the case, it don’t amount to

anything anyhow.” These flashes of wit, and others equally scintillating,

we loudly applauded, and he went on: “Tell me, my dearest Agamemnon, do

you remember the twelve labors of Hercules or the story of Ulysses, how

the Cyclops threw his thumb out of joint with a pig-headed crowbar? When I

was a boy, I used to read those stories in Homer. And then, there’s the

Sibyl: with my own eyes I saw her, at Cumae, hanging up in a jar; and

whenever the boys would say to her ‘Sibyl, Sibyl, what would you?’ she

would answer, ‘I would die.’”