CHAPTER THE FORTY-NINTH.

Before he had run out of wind, a tray upon which was an enormous hog was

placed upon the table, almost filling it up. We began to wonder at the

dispatch with which it had been prepared and swore that no cock could have

been served up in so short a time; moreover, this hog seemed to us far

bigger than the boar had been. Trimalchio scrutinized it closely and “What

the hell,” he suddenly bawled out, “this hog hain’t been gutted, has it?

No, it hain’t, by Hercules, it hain’t! Call that cook! Call that cook in

here immediately!” When the crestfallen cook stood at the table and owned

up that he had forgotten to bowel him, “So you forgot, did you?”

Trimalchio shouted, “You’d think he’d only left out a bit of pepper and

cummin, wouldn’t you? Off with his clothes!” The cook was stripped without

delay, and stood with hanging head, between two torturers. We all began to

make excuses for him at this, saying, “Little things like that are bound

to happen once in a while, let us prevail upon you to let him off; if he

ever does such a thing again, not a one of us will have a word to say in

his behalf.” But for my part, I was mercilessly angry and could not help

leaning over towards Agamemnon and whispering in his ear, “It is easily

seen that this fellow is criminally careless, is it not? How could anyone

forget to draw a hog? If he had served me a fish in that fashion I

wouldn’t overlook it, by Hercules, I wouldn’t.” But that was not

Trimalchio’s way: his face relaxed into good humor and he said, “Since

your memory’s so short, you can gut him right here before our eyes!” The

cook put on his tunic, snatched up a carving knife, with a trembling hand,

and slashed the hog’s belly in several places. Sausages and meat-

puddings, widening the apertures, by their own weight, immediately tumbled

out.

CHAPTER THE FIFTIETH.

The whole household burst into unanimous applause at this; “Hurrah for

Gaius,” they shouted. As for the cook, he was given a drink and a silver

crown and a cup on a salver of Corinthian bronze. Seeing that Agamemnon

was eyeing the platter closely, Trimalchio remarked, “I’m the only one

that can show the real Corinthian!” I thought that, in his usual

purse-proud manner, he was going to boast that his bronzes were all

imported from Corinth, but he did even better by saying, “Wouldn’t you

like to know how it is that I’m the only one that can show the real

Corinthian? Well, it’s because the bronze worker I patronize is named

Corinthus, and what’s Corinthian unless it’s what a Corinthus makes? And,

so you won’t think I’m a blockhead, I’m going to show you that I’m well

acquainted with how Corinthian first came into the world. When Troy was

taken, Hannibal, who was a very foxy fellow and a great rascal into the

bargain, piled all the gold and silver and bronze statues in one pile and

set ‘em afire, melting these different metals into one: then the metal

workers took their pick and made bowls and dessert dishes and statuettes

as well. That’s how Corinthian was born; neither one nor the other, but an

amalgam of all. But I prefer glass, if you don’t mind my saying so; it

don’t stink, and if it didn’t break, I’d rather have it than gold, but

it’s cheap and common now.”

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-FIRST.

“But there was an artisan, once upon a time, who made a glass vial that

couldn’t be broken. On that account he was admitted to Caesar with his

gift; then he dashed it upon the floor, when Caesar handed it back to him.

The Emperor was greatly startled, but the artisan picked the vial up off

the pavement, and it was dented, just like a brass bowl would have been!

He took a little hammer out of his tunic and beat out the dent without any

trouble. When he had done that, he thought he would soon be in Jupiter’s

heaven, and more especially when Caesar said to him, ‘Is there anyone else

who knows how to make this malleable glass? Think now!’ And when he denied

that anyone else knew the secret, Caesar ordered his head chopped off,

because if this should get out, we would think no more of gold than we

would of dirt.”

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-SECOND.

“And when it comes to silver, I’m a connoisseur; I have goblets as big as wine-jars, a hundred of ‘em more or less, with engraving that shows how Cassandra killed her sons, and the dead boys are lying so naturally that you’d think ‘em alive. I own a thousand bowls which Mummius left to my patron, where Daedalus is shown shutting Niobe up in the Trojan horse, and I also have cups engraved with the gladiatorial contests of Hermeros and Petraites: they’re all heavy, too. I wouldn’t sell my taste in these matters for any money!” A slave dropped a cup while he was running on in this fashion. Glaring at him, Trimalchio said, “Go hang yourself, since you’re so careless.” The boy’s lip quivered and he immediately commenced to beg for mercy. “Why do you pray to me?” Trimalchio demanded, at this: “I don’t intend to be harsh with you, I’m only warning you against being so awkward.” Finally, however, we got him to give the boy a pardon and no sooner had this been done than the slave started running around the room crying, “Out with the water and in with the wine!” We all paid tribute to this joke, but Agamemnon in particular, for he well knew what strings to pull in order to secure another invitation to dinner. Tickled by our flattery, and mellowed by the wine, Trimalchio was just about drunk. “Why hasn’t one of you asked my Fortunata to dance?” he demanded, “There’s no one can do a better cancan, believe me,” and he himself raised his arms above his head and favored us with an impersonation of Syrus the actor; the whole household chanting:

Oh bravo

Oh bravissimo

in chorus, and he would have danced out into the middle of the room before

us all, had not Fortunata whispered in his ear, telling him, I suppose,

that such low buffoonery was not in keeping with his dignity. But nothing

could be so changeable as his humor, for one minute he stood in awe of

Fortunata, but his natural propensities would break out the next.

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-THIRD.

But his passion for dancing was interrupted at this stage by a

stenographer who read aloud, as if he were reading the public records, “On

the seventh of the Kalends of July, on Trimalchio’s estates near Cumae,

were born thirty boys and forty girls: five hundred pecks of wheat were

taken from the threshing floors and stored in the granaries: five hundred

oxen were put to yoke: the slave Mithridates was crucified on the same

date for cursing the genius of our master, Gaius: on said date ten million

sesterces were returned to the vaults as no sound investment could be

found: on said date, a fire broke out in the gardens at Pompeii, said fire

originating in the house of Nasta, the bailiff.” “What’s that?” demanded

Trimalchio. “When were the gardens at Pompeii bought for me?” “Why, last

year,” answered the stenographer, “for that reason the item has not

appeared in the accounts.” Trimalchio flew into a rage at this. “If I’m

not told within six months of any real estate that’s bought for me,” he

shouted, “I forbid it’s being carried to my account at all!” Next, the

edicts of his aediles were read aloud, and the wills of some of his

foresters in which Trimalchio was disinherited by a codicil, then the

names of his bailiffs, and that of a freedwoman who had been repudiated by

a night watchman, after she had been caught in bed with a bath attendant,

that of a porter banished to Baioe, a steward who was standing trial, and

lastly the report of a decision rendered in the matter of a lawsuit,

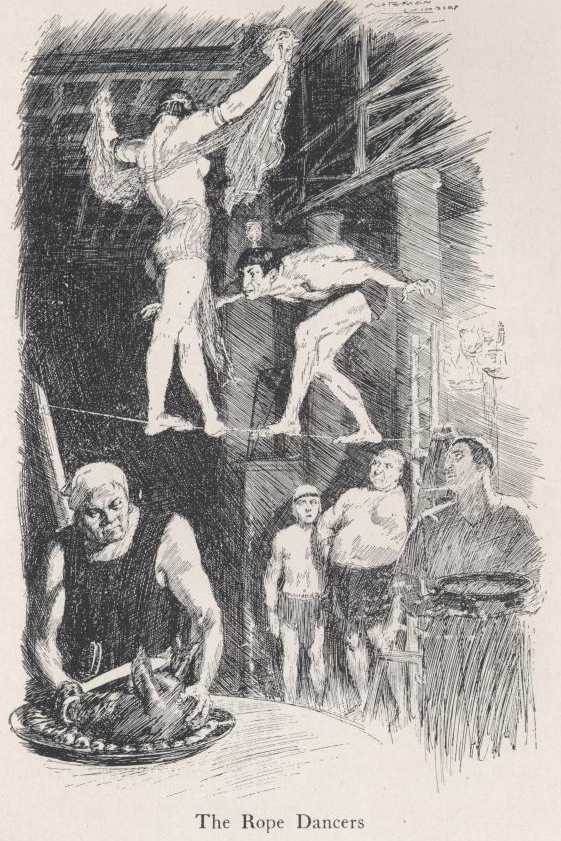

between some valets. When this was over with, some rope dancers came in

and a very boresome fool stood holding a ladder, ordering his boy to dance

from rung to rung, and finally at the top, all this to the music of

popular airs; then the boy was compelled to jump through blazing hoops

while grasping a huge wine jar with his teeth. Trimalchio was the only one

who was much impressed by these tricks, remarking that it was a thankless

calling and adding that in all the world there were just two things which

could give him acute pleasure, rope-dancers and horn blowers; all other

entertainments were nothing but nonsense. “I bought a company of

comedians,” he went on, “but I preferred for them to put on Atellane

farces, and I ordered my flute-player to play Latin airs only.”

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-FOURTH.

While our noble Gaius was still talking away, the boy slipped and fell,

alighting upon Trimalchio’s arm. The whole household cried out, as did

also the guests, not that they bore such a coarse fellow any good will, as

they would gladly have seen his neck broken, but because such an unlucky

ending to the dinner might make it necessary for them to go into mourning

over a total stranger. As for Trimalchio, he groaned heavily and bent over

his arm as though it had been injured: doctors flocked around him, and

Fortunata was among the very first, her hair was streaming and she held a

cup in her hand and screamed out her grief and unhappiness. As for the boy

who had fallen, he was crawling at our feet, imploring pardon. I was

uneasy for fear his prayers would lead up to some ridiculous theatrical

climax, for I had not yet been able to forget that cook who had forgotten

to bowel that hog, and so, for this reason, I began to scan the whole

dining-room very closely, to see if an automaton would come out through

the wall; and all the more so as a slave was beaten for having bound up

his master’s bruised arm in white wool instead of purple. Nor was my

suspicion unjustified, for in place of punishment, Trimalchio ordered that

the boy be freed, so that no one could say that so exalted a personage had

been injured by a slave.

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-FIFTH.

We applauded his action and engaged in a discussion upon the instability of human affairs, which many took sides. “A good reason,” declared Trimalchio, “why such an occasion shouldn’t slip by without an epigram.” He called for his tablets at once, and after racking his brains for a little while, he got off the following:

The unexpected will turn up;

Our whole lives Fortune bungles up.

Falernian, boy, hand round the cup.

This epigram led up to a discussion of the poets, and for a long time, the greatest praise was bestowed upon Mopsus the Thracian, until Trimalchio broke in with: “Professor, I wish you’d tell me how you’d compare Cicero and Publilius. I’m of the opinion that the first was the more eloquent, but that the last moralizes more beautifully, for what can excel these lines?

Insatiable luxury crumbles the walls of war;

To satiate gluttony, peacocks in coops are brought

Arrayed in gold plumage like Babylon tapestry rich.

Numidian guinea-fowls, capons, all perish for thee:

And even the wandering stork, welcome guest that he is,

The emblem of sacred maternity, slender of leg

And gloctoring exile from winter, herald of spring,

Still, finds his last nest in the--cauldron of gluttony base.

India surrenders her pearls; and what mean they to thee?

That thy wife decked with sea-spoils adorning her breast and her head

On the couch of a stranger lies lifting adulterous legs?

The emerald green, the glass bauble, what mean they to thee?

Or the fire of the ruby? Except that pure chastity shine

From the depth of the jewels: in garments of woven wind clad

Our brides might as well take their stand, their game naked to stalk,

As seek it in gossamer tissue transparent as air.”

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-SIXTH.

“What should we say was the hardest calling, after literature?” he asked.

“That of the doctor or that of the money-changer, I would say: the doctor,

because he has to know what poor devils have got in their insides, and

when the fever’s due: but I hate them like the devil, for my part, because

they’re always ordering me on a diet of duck soup: and the

money-changer’s, because he’s got to be able to see the silver through the

copper plating. When we come to the dumb beasts, the oxen and sheep are

the hardest worked, the oxen, thanks to whose labor we have bread to chew

on, the sheep, because their wool tricks us out so fine. It’s the greatest

outrage under the sun for people to eat mutton and then wear a tunic. Then

there’s the bee: in my opinion, they’re divine insects because they puke

honey, though there are folks that claim that they bring it from Jupiter,

and that’s the reason they sting, too, for wherever you find a sweet,

you’ll find a bitter too.” He was just putting the philosophers out of

business when lottery tickets were passed around in a cup. A slave boy

assigned to that duty read aloud the names of the souvenirs: “Silver

s--ham,” a ham was brought in with some silver vinegar cruets on top of

it; “cervical"--something soft for the neck--a piece of the

cervix--neck--of a sheep was brought in; “serisapia"--after wit--“and

contumelia"--insult--we were given must wafers and an apple-melon--and a

phallus--contus--; “porri"--leeks--“and persica,” he picked up a whip and

a knife; “passeres"--sparrows” and a fly--trap,” the answer was

raisins--uva passa--and Attic honey; “cenatoria"--a dinner toga--“and

forensia"--business dress--he handed out a piece of meat--suggestive of

dinner--and a note-book--suggestive of business--; “canale"--chased by a

dog--“and pedale"--pertaining to the foot--, a hare and a slipper were

brought out; “lamphrey"--murena--“and a letter,” he held up a

mouse--mus--and a frog--rana--tied together, and a bundle of

beet--beta--the Greek letter beta--. We laughed long and loud, there were

a thousand of these jokes, more or less, which have now escaped my memory.

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-SEVENTH.

But Ascyltos threw off all restraint and ridiculed everything; throwing up

his hands, he laughed until the tears ran down his cheeks. At last, one of

Trimalchio’s fellow-freedmen, the one who had the place next to me, flew

into a rage, “What’s the joke, sheep’s-head,” he bawled, “Don’t our host’s

swell entertainment suit you? You’re richer than he is, I suppose, and

used to dining better! As I hope the guardian spirit of this house will be

on my side, I’d have stopped his bleating long ago if I’d been sitting

next to him. He’s a peach, he is, laughing at others; some vagabond or

other from who-knows-where, some night-pad who’s not worth his own piss:

just let me piss a ring around him and he wouldn’t know where to run to! I

ain’t easy riled, no, by Hercules, I ain’t, but worms breed in tender

flesh. Look at him laugh! What the hell’s he got to laugh at? Is his

family so damned fine-haired? So you’re a Roman knight! Well, I’m a king’s

son! How’s it come that you’ve been a slave, you’ll ask because I put

myself into service because I’d rather be a Roman citizen than a

tax-paying provincial. And now I hope that my life will be such that no

one can jeer at me. I’m a man among men! I take my stroll bareheaded and

owe no man a copper cent. I never had a summons in my life and no one ever

said to me, in the forum, pay me what you owe me. I’ve bought a few acres

and saved up a few dollars and I feed twenty bellies and a dog. I ransomed

my bedfellow so no one could wipe his hands on her bosom; a thousand

dinars it cost me, too. I was chosen priest of Augustus without paying the

fee, and I hope that I won’t need to blush in my grave after I’m dead. But

you’re so busy that you can’t look behind you; you can spot a louse on

someone else, all right, but you can’t see the tick on yourself. You’re

the only one that thinks we’re so funny; look at your professor, he’s

older than you are, and we’re good enough for him, but you’re only a brat

with the milk still in your nose and all you can prattle is ‘ma’ or ‘mu,’

you’re only a clay pot, a piece of leather soaked in water, softer and

slipperier, but none the better for that. You’ve got more coin than we

have, have you? Then eat two breakfasts and two dinners a day. I’d rather

have my reputation than riches, for my part, and before I make an end of

this--who ever dunned me twice? In all the forty years I was in service,

no one could tell whether I was free or a slave. I was only a long-haired

boy when I came to this colony and the town house was not built then. I

did my best to please my master and he was a digniferous and majestical

gentleman whose nail-parings were worth more than your whole carcass. I

had enemies in his house, too, who would have been glad to trip me up, but

I swam the flood, thanks to his kindness. Those are the things that try

your mettle, for it’s as easy to be born a gentleman as to say, ‘Come

here.’ Well, what are you gaping at now, like a billy-goat in a

vetch-field?”

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-EIGHTH.

Giton, who had been standing at my feet, and who had for some time been holding in his laughter, burst into an uproarious guffaw, at this last figure of speech, and when Ascyltos’ adversary heard it, he turned his abuse upon the boy. “What’s so funny, you curly-headed onion,” he bellowed, “are the Saturnalia here, I’d like to know? Is it December now?

“When did you pay your twentieth? What’s this to you, you gallows-bird,

you crow’s meat? I’ll call the anger of Jupiter down on you and that

master of yours, who don’t keep you in better order. If I didn’t respect

my fellow-freedmen, I’d give you what is coming to you right here on the

spot, as I hope to get my belly full of bread, I would. We’ll get along

well enough, but those that can’t control you are fools; like master like

man’s a true saying. I can hardly hold myself in and I’m not hot-headed by

nature, but once let me get a start and I don’t care two cents for my own

mother. All right, I’ll catch you in the street, you rat, you toadstool.

May I never grow an inch up or down if I don’t push your master into a

dunghill, and I’ll give you the same medicine, I will, by Hercules, I

will, no matter if you call down Olympian Jupiter himself! I’ll take care

of your eight inch ringlets and your two cent master into the bargain.

I’ll have my teeth into you, either you’ll cut out the laughing, or I

don’t know myself. Yes, even if you had a golden beard. I’ll bring the

wrath of Minerva down on you and on the fellow that first made a come-here

out of you. No, I never learned geometry or criticism or other foolishness

like that, but I know my capital letters and I can divide any figure by a

hundred, be it in asses, pounds or sesterces. Let’s have a show-down, you

and I will make a little bet, here’s my coin; you’ll soon find out that

your father’s money was wasted on your education, even if you do know a

little rhetoric. How’s this--what part of us am I? I come far, I come

wide, now guess me! I’ll give you another. What part of us runs but never

moves from its place? What part of us grows but always grows less? But you

scurry around and are as flustered and fidgeted as a mouse in a piss-pot.

Shut up and don’t annoy your betters, who don’t even know that you’ve been

born. Don’t think that I’m impressed by those boxwood armlets that you did

your mistress out of. Occupo will back me! Let’s go into the forum and

borrow money, then you’ll see whether this iron ring means credit! Bah! A

draggled fox is a fine sight, ain’t it’? I hope I never get rich and die

decently so that the people will swear by my death, if I don’t hound you

everywhere with my toga turned inside out. And the fellow that taught you

such manners did a good job too, a chattering ape, all right, no

schoolmaster. We were better taught. ‘Is everything in its place?’ the

master would ask; go straight home and don’t stop and stare at everything

and don’t be impudent to your elders. Don’t loiter along looking in at the

shops. No second raters came out of that school. I’m what you see me and I

thank the gods it’s all due to my own cleverness.”

CHAPTER THE FIFTY-NINTH.

Ascyltos was just starting in to answer this indictment when Trimalchio,

who was delighted with his fellow-freedman’s tirade, broke in, “Cut out

the bickering and let’s have things pleasant here. Let up on the young

fellow, Hermeros, he’s hot-blooded, so you ought to be more reasonable.

The loser’s always the winner in arguments of this kind. And as for you,

even when you were a young punk you used to go ‘Co-co co-co,’ like a hen

after a rooster, but you had no pep. Let’s get to better business and

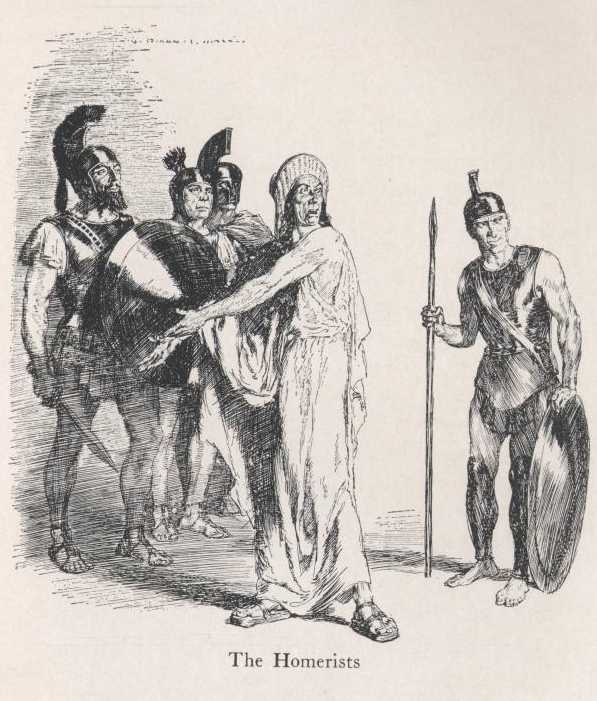

start the fun all over again and watch the Homerists.” A troupe filed in,

immediately, and clashed spears against shields. Trimalchio sat himself up

on his cushion and intoned in Latin, from a book, while the actors, in

accordance with their conceited custom, recited their parts in the Greek

language. There came a pause, presently, and “You don’t any of you know

the plot of the skit they’re putting on, do you?” he asked, “Diomedes and

Ganymede were two brothers, and Helen was their sister; Agamemnon ran away

with her and palmed off a doe on Diana, in her place, so Homer tells how

the Trojans and Parentines fought among themselves. Of course Agamemnon

was victorious, and gave his daughter Iphigenia, to Achilles, for a wife:

This caused Ajax to go mad, and he’ll soon make the whole thing plain to

you.” The Homerists raised a shout, as soon as Trimalchio had done

speaking, and, as the whole familia stepped back, a boiled calf with a

helmet on its head was brought in on an enormous platter. Ajax followed

and rushed upon it with drawn sword, as if he were insane, he made passes

with the flat, and again with the edge, and then, collecting the slices,

he skewered them, and, much to our astonishment, presented them to us on

the point of his sword.

CHAPTER THE SIXTIETH.

But we were not given long in which to admire the elegance of such

service, for all of a sudden the ceiling commenced to creak and then the

whole dining-room shook. I leaped to my feet in consternation, for fear

some rope-walker would fall down, and the rest of the company raised their

faces, wondering as much as I what new prodigy was to be announced from on

high. Then lo and behold! the ceiling panels parted and an enormous hoop,

which appeared to have been knocked off a huge cask, was lowered from the

dome above; its perimeter was hung with golden chaplets and jars of

alabaster filled with perfume. We were asked to accept these articles as

souvenirs. When my glance returned to the table, I noticed that a dish

containing cakes had been placed upon it, and in the middle an image of

Priapus, made by the baker, and he held apples of all varieties and

bunches of grapes against his breast, in the conventional manner. We

applied ourselves wholeheartedly to this dessert and our joviality was

suddenly revived by a fresh diversion, for, at the slightest pressure, all

the cakes and fruits would squirt a saffron sauce upon us, and even

spurted unpleasantly into our faces. Being convinced that these perfumed

dainties had some religious significance, we arose in a body and shouted,

“Hurrah for the Emperor, the father of his country!” However, as we

perceived that even after this act of veneration, the others continued

helping themselves, we filled our napkins with the apples. I was

especially keen on this, for I thought I could never put enough good

things into Giton’s lap. Three slaves entered, in the meantime, dressed in

white tunics well tucked up, and two of them placed Lares with amulets

hanging from their necks, upon the table, while the third carried round a

bowl of wine and cried, “May the gods be propitious!” One was called

Cerdo--business--, Trimalchio informed us, the other Lucrio--luck--and the

third Felicio--profit--and, when all the rest had kissed a true likeness

of Trimalchio, we were ashamed to pass it by.

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-FIRST.

After they had all wished each other sound minds and good health,

Trimalchio turned to Niceros. “You used to be better company at dinner,”

he remarked, “and I don’t know why you should be dumb today, with never a

word to say. If you wish to make me happy, tell about that experience you

had, I beg of you.” Delighted at the affability of his friend, “I hope I

lose all my luck if I’m not tickled to death at the humor I see you in,”

Niceros replied. “All right, let’s go the limit for a good time, though

I’m afraid these scholars’ll laugh at me, but I’ll tell my tale and they

can go as far as they like. What t’hell do I care who laughs? It’s better

to be laughed at than laughed down.” These words spake the hero, and began

the following tale: “We lived in a narrow street in the house Gavilla now

owns, when I was a slave. There, by the will of the gods, I fell in love

with the wife of Terentius, the innkeeper; you knew Melissa of Tarentum,

that pretty round-checked little wench. It was no carnal passion, so hear

me, Hercules, it wasn’t; I was not in love with her physical charms. No,

it was because she was such a good sport. I never asked her for a thing

and had her deny me; if she had an as, I had half. I trusted her with

everything I had and never was done out of anything. Her husband up and

died on the place, one day, so I tried every way I could to get to her,

for you know friends ought to show up when anyone’s in a pinch.

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-SECOND.

“It so happened that our master had gone to Capua to attend to some odds

and ends of business and I seized the opportunity, and persuaded a guest

of the house to accompany me as far as the fifth mile-stone. He was a

soldier, and as brave as the very devil. We set out about cock-crow, the

moon was shining as bright as midday, and came to where the tombstones

are. My man stepped aside amongst them, but I sat down, singing, and

commenced to count them up. When I looked around for my companion, he had

stripped himself and piled his clothes by the side of the road. My heart

was in my mouth, and I sat there while he pissed a ring around them and

was suddenly turned into a wolf! Now don’t think I’m joking, I wouldn’t

lie for any amount of money, but as I was saying, he commenced to howl

after he was turned into a wolf, and ran away into the forest. I didn’t

know where I was for a minute or two, then I went to his clothes, to pick

them up, and damned if they hadn’t turned to stone! Was ever anyone nearer

dead from fright than me? Then I whipped out my sword and cut every shadow

along the road to bits, till I came to the house of my mistress. I looked

like a ghost when I went in, and I nearly slipped my wind. The sweat was

pouring down my crotch, my eyes were staring, and I could hardly be

brought around. My Melissa wondered why I was out so late. “Oh, if you’d

only come sooner,” she said, “you could have helped us: a wolf broke into

the folds and attacked the sheep, bleeding them like a butcher. But he

didn’t get the laugh on me, even if he did get away, for one of the slaves

ran his neck through with a spear!” I couldn’t keep my eyes shut any

longer when I heard that, and as soon as it grew light, I rushed back to

our Gaius’ house like an innkeeper beaten out of his bill, and when I came

to the place where the clothes had been turned into stone, there was

nothing but a pool of blood! And moreover, when I got home, my soldier was

lying in bed, like an ox, and a doctor was dressing his neck! I knew then

that he was a werewolf, and after that, I couldn’t have eaten a crumb of

bread with him, no, not if you had killed me. Others can think what they

please about this, but as for me, I hope your geniuses will all get after

me if I lie.”

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-THIRD.

We were all dumb with astonishment, when “I take your story for granted,”

said Trimalchio, “and if you’ll believe me, my hair stood on end, and all

the more, because I know that Niceros never talks nonsense: he’s always

level-headed, not a bit gossipy. And now I’ll tell you a hair-raiser

myself, though I’m like a jackass on a slippery pavement compared to him.

When I was a long-haired boy, for I lived a Chian life from my youth up,

my master’s minion died. He was a jewel, so hear me Hercules, he was,

perfect in every facet. While his sorrow-stricken mother was bewailing his

loss, and the rest of us were lamenting with her, the witches suddenly

commenced to screech so loud that you would have thought a hare was being

run down by the hounds! At that time, we had a Cappadocian slave, tall,

very bold, and he had muscle too; he could hold a mad bull in the air! He

wrapped a mantle around his left arm, boldly rushed out of doors with

drawn sword, and ran a woman through the middle about here, no harm to

what I touch. We heard a scream, but as a matter of fact, for I won’t lie

to you, we didn’t catch sight of the witches themselves. Our simpleton

came back presently, and threw himself upon the bed. His whole body was

black and blue, as if he had been flogged with whips, and of course the

reason of that was she had touched him with her evil hand! We shut the

door and returned to our business, but when the mother put her arms around

the body of her son, it turned out that it was only a straw bolster, no

heart, no guts, nothing! Of course the witches had swooped down upon the

lad and put the straw changeling in his place! Believe me or not, suit

yourselves, but I say that there are women that know too much, and

night-hags, too, and they turn everything upside down! And as for the

long-haired booby, he never got back his own natural color and he died,

raving mad, a few days later.”

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-FOURTH.

Though we wondered greatly, we believed none the less implicitly and,

kissing the table, we besought the night-hags to attend to their own

affairs while we were returning home from dinner. As far as I was

concerned, the lamps already seemed to burn double and the whole

dining-room was going round, when “See here, Plocamus,” Trimalchio spoke

up, “haven’t you anything to tell us? You haven’t entertained us at all,

have you? And you used to be fine company, always ready to oblige with a

recitation or a song. The gods bless us, how the green figs have fallen!”

“True for you,” the fellow answered, “since I’ve got the gout my sporting

days are over; but in the good old times when I was a young spark, I

nearly sang myself into a consumption. How I used to dance! And take my

part in a farce, or hold up my end in the barber shops! Who could hold a

candle to me except, of course, the one and only Apelles?” He then put his

hand to his mouth and hissed out some foul gibberish or other, and said

afterwards that it was Greek. Trimalchio himself then favored us with an

impersonation of a man blowing a trumpet, and when he had finished, he

looked around for his minion, whom he called Croesus, a blear-eyed slave

whose teeth were very disagreeably discolored. He was playing with a

little black bitch, disgustingly fat, wrapping her up in a leek-green

scarf and teasing her with a half-loaf of bread which he had put on the

couch; and when from sheer nausea, she refused it, he crammed it down her

throat. This sight put Trimalchio in mind of his own dog and he ordered

Scylax, “the guardian of his house and home,” to be brought in. An

enormous dog was immediately led in upon a chain and, obeying a kick from

the porter, it lay down beside the table. Thereupon Trimalchio remarked,

as he threw it a piece of white bread, “No one in all my house loves me

better than Scylax.” Enraged at Trimalchio’s praising Scylax so warmly,

the slave put the bitch down upon the floor and sicked her on to fight.

Scylax, as might have been expected from such a dog, made the whole room

ring with his hideous barking and nearly shook the life out of the little

bitch which the slave called Pearl. Nor did the uproar end in a dog fight,

a candelabrum was upset upon the table, breaking the glasses and

spattering some of the guests with hot oil. As Trimalchio did not wish to

seem concerned at the loss, he kissed the boy and ordered him to climb

upon his own back. The slave did not hesitate but, mounting his

rocking-horse, he beat Trimalchio’s shoulders with his open palms, yelling

with laughter, “Buck! Buck! How many fingers do I hold up!” When

Trimalchio had, in a measure, regained his composure, which took but a

little while, he ordered that a huge vessel be filled with mixed wine, and

that drinks be served to all the slaves sitting around our feet, adding as

an afterthought, “If anyone refuses to drink, pour it on his head:

business is business, but now’s the time for fun.”

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-FIFTH.

The dainties that followed this display of affability were of such a

nature that, if any reliance is to be placed in my word, the very mention

of them makes me sick at the stomach. Instead of thrushes, fattened

chickens were served, one to each of us, and goose eggs with pastry caps

on them, which same Trimalchio earnestly entreated us to eat, informing us

that the chickens had all been boned. Just at that instant, however, a

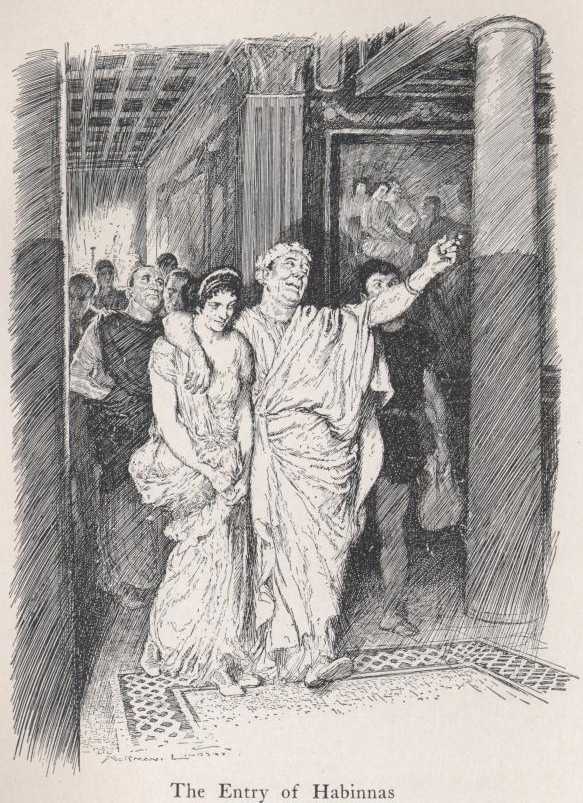

lictor knocked at the dining-room door, and a reveler, clad in white

vestments, entered, followed by a large retinue. Startled at such pomp, I

thought that the Praetor had arrived, so I put my bare feet upon the floor

and started to get up, but Agamemnon laughed at my anxiety and said, “Keep

your seat, you idiot, it’s only Habinnas the sevir; he’s a stone mason,

and if report speaks true, he makes the finest tombstones imaginable.”

Reassured by this information, I lay back upon my couch and watched

Habinnas’ entrance with great curiosity. Already drunk and wearing several

wreaths, his forehead smeared with perfume which ran down into his eyes,

he advanced with his hands upon his wife’s shoulders, and, seating himself

in the Praetor’s place, he called for wine and hot water. Delighted with

his good humor, Trimalchio called for a larger goblet for himself, and

asked him, at the same time, how he had been entertained. “We had

everything except yourself, for my heart and soul were here, but it was

fine, it was, by Hercules. Scissa was giving a Novendial feast for her

slave, whom she freed on his death-bed, and it’s my opinion she’ll have a

large sum to split with the tax gatherers, for the dead man was rated at

50,000, but everything went off well, even if we did have to pour half our

wine on the bones of the late lamented.”

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-SIXTH.

“But,” demanded Trimalchio, “what did you have for dinner’?” “I’ll tell

you if I can,” answered he, “for my memory’s so good that I often forget

my own name. Let’s see, for the first course, we had a hog, crowned with a

wine cup and garnished with cheese cakes and chicken livers cooked well

done, beets, of course, and whole-wheat bread, which I’d rather have than

white, because it puts strength into you, and when I take a crap

afterwards, I don’t have to yell. Following this, came a course of tarts,

served cold, with excellent Spanish wine poured over warm honey; I ate

several of the tarts and got the honey all over myself. Then there were

chick-peas and lupines, all the smooth-shelled nuts you wanted, and an

apple apiece, but I got away with two, and here they are, tied up in my

napkin; for I’ll have a row on my hands if I don’t bring some kind of a

present home to my favorite slave. Oh yes, my wife has just reminded me,

there was a haunch of bear-meat as a side dish, Scintilla ate some of it

without knowing what it was, and she nearly puked up her guts when she

found out. But as for me, I ate more than a pound of it, for it tasted

exactly like wild boar and, says I, if a bear eats a man, shouldn’t that

be all the more reason for a man to eat a bear? The last course was soft

cheese, new wine boiled thick, a snail apiece, a helping of tripe, liver

pate, capped eggs, turnips and mustard. But that’s enough. Pickled olives

were handed around in a wooden bowl, and some of the party greedily

snatched three handfuls, we had ham, too, but we sent it back.”

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-SEVENTH.

“But why isn’t Fortunata at the table, Gaius? Tell me.” “What’s that,” Trimalchio replied; “don’t you know her better than that? She wouldn’t touch even a drop of water till after the silver was put away and the leftovers divided among the slaves.” “I’m going to beat it if she don’t take her place,” Habinnas threatened, and started to get up; and then, at a signal, the slaves all called out together “Fortunata,” four times or more.

She appeared, girded round with a sash of greenish yellow, below which a

cherry-colored tunic could be seen, and she had on twisted anklets and

sandals worked in gold. Then, wiping her hands upon a handkerchief which

she wore around her neck, she seated herself upon the couch, beside

Scintilla, Habinnas’ wife, and clapping her hands and kissing her, “My

dear,” she gushed, “is it really you?” Fortunata then removed the

bracelets from her pudgy arms and held them out to the admiring Scintilla,

and by and by she took off her anklets and even her yellow hair-net, which

was twenty-four carats fine, she would have us know! Trimalchio, who was

on the watch, ordered every trinket to be brought to him. “You see these

things, don’t you?” he demanded; “they’re what women fetter us with.

That’s the way us poor suckers are done! These ought to weigh six pounds

and a half. I have an arm-band myself, that don’t weigh a grain under ten

pounds; I bought it out of Mercury’s thousandths, too.” Finally, for fear

he would seem to be lying, he ordered the scales to be brought in and

carried around to prove the weights. And Scintilla was no better. She took

off a small golden vanity case which she wore around her neck, and which

she called her Lucky Box, and took from it two eardrops, which, in her

turn, she handed to Fortunata to be inspected. “Thanks to the generosity

of my husband,” she smirked, “no woman has better.” “What’s that?”

Habinnas demanded. “You kept on my trail to buy that glass bean for you;

if I had a daughter, I’ll be damned if I wouldn’t cut off her little ears.

We’d have everything as cheap as dirt if there were no women, but we have

to piss hot and drink cold, the way things are now.” The women, angry

though they were, were laughing together, in the meantime, and exchanging

drunken kisses, the one running on about her diligence as a housekeeper,

and the other about the infidelities and neglect of her husband. Habinnas

got up stealthily, while they were clinging together in this fashion and,

seizing Fortunata by the feet, he tipped her over backwards upon the

couch. “Let go!” she screeched, as her tunic slipped above her knees;

then, after pulling down her clothing, she threw herself into Scintilla’s

lap, and hid, with her handkerchief, a face which was none the more

beautiful for its blushes.

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-EIGHTH.

After a short interval, Trimalchio gave orders for the dessert to be

served, whereupon the slaves took away all the tables and brought in

others, and sprinkled the floor with sawdust mixed with saffron and

vermilion, and also with powdered mica, a thing I had never seen done

before. When all this was done Trimalchio remarked, “I could rest content

with this course, for you have your second tables, but, if you’ve

something especially nice, why bring it on.” Meanwhile an Alexandrian

slave boy, who had been serving hot water, commenced to imitate a

nightingale, and when Trimalchio presently called out, “Change your tune,”

we had another surprise, for a slave, sitting at Habinnas’ feet, egged on,

I have no doubt, by his own master, bawled suddenly in a singsong voice,

“Meanwhile AEneas and all of his fleet held his course on the billowy

deep”; never before had my ears been assailed by a sound so discordant,

for in addition to his barbarous pronunciation, and the raising and

lowering of his voice, he interpolated Atellane verses, and, for the first

time in my life, Virgil grated on my nerves. When he had to quit, finally,

from sheer want of breath, “Did he ever have any training,” Habinnas

exclaimed, “no, not he! I educated him by sending him among the grafters

at the fair, so when it comes to taking off a barker or a mule driver,

there’s not his equal, and the rogue’s clever, too, he’s a shoemaker, or a

cook, or a baker a regular jack of all trades. But he has two faults, and

if he didn’t have them, he’d be beyond all price: he snores and he’s been

circumcised. And that’s the reason he never can keep his mouth shut and

always has an eye open. I paid three hundred dinars for him.”

CHAPTER THE SIXTY-NINTH.

“Yes,” Scintilla broke in, “and you’ve not mentioned all of his

accomplishments either; he’s a pimp too, and I’m going to see that he’s

branded,” she snapped. Trimalchio laughed. “There’s where the Cappadocian

comes out,” he said; “never cheats himself out of anything and I admire

him for it, so help me Hercules, I do. No one can show a dead man a good

time. Don’t be jealous, Scintilla; we’re next to you women, too, believe

me. As sure as you see me here safe and sound, I used to play at thrust

and parry with Mamma, my mistress, and finally even my master got

suspicious and sent me back to a stewardship; but keep quiet, tongue, and

I’ll give you a cake.” Taking all this as praise, the wretched slave

pulled a small earthen lamp from a fold in his garment, and impersonated a

trumpeter for half an hour or more, while Habinnas hummed with him,

holding his finger pressed to his lips. Finally, the slave stepped out

into the middle of the floor and waved his pipes in imitation of a

flute-player; then, with a whip and a smock, he enacted the part of a

mule-driver. At last Habinnas called him over and kissed him and said, as

he poured a drink for him, “You get better all the time, Massa. I’m going

to give you a pair of shoes.” Had not the dessert been brought in, we

would never have gotten to the end of these stupidities. Thrushes made of

pastry and stuffed with nuts and raisins, quinces with spines sticking out

so that they looked like sea-urchins. All this would have been endurable

enough had it not been for the last dish that was served; so revolting was

this, that we would rather have died of starvation than to have even

touched it. We thought that a fat goose, flanked with fish and all kinds

of birds, had been served, until Trimalchio spoke up. “Everything you see

here, my friends,” said he, “was made from the same stuff.” With my usual

keen insight, I jumped to the conclusion that I knew what that stuff was

and, turning to Agamemnon, I said, “I shall be greatly surprised, if all

those things are not made out of excrement, or out of mud, at the very

least: I saw a like artifice practiced at Rome during the Saturnalia.”