CHAPTER THE SEVENTIETH.

I had not done speaking, when Trimalchio chimed in, “As I hope to grow

fatter in fortune but not in figure, my cook has made all this out of a

hog! It would be simply impossible to meet up with a more valuable fellow:

he’d make you a fish out of a sow’s coynte, if that’s what you wanted, a

pigeon out of her lard, a turtle-dove out of her ham, and a hen out of a

knuckle of pork: that’s why I named him Daedalus, in a happy moment. I

brought him a present of knives, from Rome, because he’s so smart; they’re

made of Noric steel, too.” He ordered them brought in immediately, and

looked them over, with admiration, even giving us the chance to try their

edges upon our cheeks. Then all of a sudden two slaves came in, carrying

on as if they had been fighting at the fountain, at least; each one had a

water-jar hanging from a yoke around his neck. Trimalchio arbitrated their

difference, but neither would abide by his decision, and each one smashed

the other’s jar with a club. Perturbed at the insolence of these drunken

ruffians, we watched both of them narrowly, while they were fighting, and

then, what should come pouring out of the broken jars but oysters and

scallops, which a slave picked up and passed around in a dish. The

resourceful cook would not permit himself to be outdone by such

refinements, but served us with snails on a silver gridiron, and sang

continually in a tremulous and very discordant voice. I am ashamed to have

to relate what followed, for, contrary to all convention, some long-haired

boys brought in unguents in a silver basin and anointed the feet of the

reclining guests; but before doing this, however, they bound our thighs

and ankles with garlands of flowers. They then perfumed the wine-mixing

vessel with the same unguent and poured some of the melted liquid into the

lamps. Fortunata had, by this time, taken a notion that she wanted to

dance, and Scintilla was doing more hand-clapping than talking, when

Trimalchio called out, “Philargyrus, and you too, Carrio, you can both

come to the table; even if you are green faction fans, and tell your

bedfellow, Menophila, to come too.” What would you think happened then? We

were nearly crowded off the couches by the mob of slaves that crowded into

the dining-room and almost filled it full. As a matter of fact, I noticed

that our friend the cook, who had made a goose out of a hog, was placed

next to me, and he stunk from sauces and pickle. Not satisfied with a

place at the table, he immediately staged an impersonation of Ephesus the

tragedian, and then he suddenly offered to bet his master that the greens

would take first place in the next circus games.

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-FIRST.

Trimalchio was hugely tickled at this challenge. “Slaves are men, my friends,” he observed, “but that’s not all, they sucked the same milk that we did, even if hard luck has kept them down; and they’ll drink the water of freedom if I live: to make a long story short, I’m freeing all of them in my will. To Philargyrus, I’m leaving a farm, and his bedfellow, too. Carrio will get a tenement house and his twentieth, and a bed and bedclothes to boot. I’m making Fortunata my heir and I commend her to all my friends. I announce all this in public so that my household will love me as well now as they will when I’m dead.” They all commenced to pay tribute to the generosity of their master, when he, putting aside his trifling, ordered a copy of his will brought in, which same he read aloud from beginning to end, to the groaning accompaniment of the whole household. Then, looking at Habinnas, “What say you, my dearest friend,” he entreated; “you’ll construct my monument in keeping with the plans I’ve given you, won’t you? I earnestly beg that you carve a little bitch at the feet of my statue, some wreaths and some jars of perfume, and all of the fights of Petraites. Then I’ll be able to live even after I’m dead, thanks to your kindness. See to it that it has a frontage of one hundred feet and a depth of two hundred. I want fruit trees of every kind planted around my ashes; and plenty of vines, too, for it’s all wrong for a man to deck out his house when he’s alive, and then have no pains taken with the one he must stay in for a longer time, and that’s the reason I particularly desire that this notice be added:

--THIS MONUMENT DOES NOT--

--DESCEND TO AN HEIR--

“In any case, I’ll see to it through a clause in my will, that I’m not insulted when I’m dead. And for fear the rabble comes running up into my monument, to crap, I’ll appoint one of my freedmen custodian of my tomb. I want you to carve ships under full sail on my monument, and me, in my robes of office, sitting on my tribunal, five gold rings on my fingers, pouring out coin from a sack for the people, for I gave a dinner and two dinars for each guest, as you know. Show a banquet-hall, too, if you can, and the people in it having a good time. On my right, you can place a statue of Fortunata holding a dove and leading a little bitch on a leash, and my favorite boy, and large jars sealed with gypsum, so the wine won’t run out; show one broken and a boy crying over it. Put a sun-dial in the middle, so that whoever looks to see what time it is must read my name whether he wants to or not. As for the inscription, think this over carefully, and see if you think it’s appropriate:

HERE RESTS G POMPEIUS TRIMALCHIO

FREEDMAN OF MAECENAS DECREED

AUGUSTAL, SEVIR IN HIS ABSENCE

HE COULD HAVE BEEN A MEMBER OF

EVERY DECURIA OF ROME BUT WOULD

NOT CONSCIENTIOUS BRAVE LOYAL

HE GREW RICH FROM LITTLE AND LEFT

THIRTY MILLION SESTERCES BEHIND

HE NEVER HEARD A PHILOSOPHER

FAREWELL TRIMALCHIO

FAREWELL PASSERBY”

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-SECOND.

When he had repeated these words, Trimalchio began to weep copiously,

Fortunata was crying already, and so was Habinnas, and at last, the whole

household filled the dining-room with their lamentations, just as if they

were taking part in a funeral. Even I was beginning to sniffle, when

Trimalchio said, “Let’s live while we can, since we know we’ve all got to

die. I’d rather see you all happy, anyhow, so let’s take a plunge in the

bath. You’ll never regret it. I’ll bet my life on that, it’s as hot as a

furnace!” “Fine business,” seconded Habinnas, “there’s nothing suits me

better than making two days out of one,” and he got up in his bare feet to

follow Trimalchio, who was clapping his hands. I looked at Ascyltos. “What

do you think about this?” I asked. “The very sight of a bath will be the

death of me.” “Let’s fall in with his suggestion,” he replied, “and while

they are hunting for the bath we will escape in the crowd.” Giton led us

out through the porch, when we had reached this understanding, and we came

to a door, where a dog on a chain startled us so with his barking that

Ascyltos immediately fell into the fish-pond. As for myself, I was tipsy

and had been badly frightened by a dog that was only a painting, and when

I tried to haul the swimmer out, I was dragged into the pool myself. The

porter finally came to our rescue, quieted the dog by his appearance, and

pulled us, shivering, to dry land. Giton had ransomed himself by a very

cunning scheme, for what we had saved for him, from dinner, he threw to

the barking brute, which then calmed its fury and became engrossed with

the food. But when, with chattering teeth, we besought the porter to let

us out at the door, “If you think you can leave by the same door you came

in at,” he replied, “you’re mistaken: no guest is ever allowed to go out

through the same door he came in at; some are for entrance, others for

exit.”

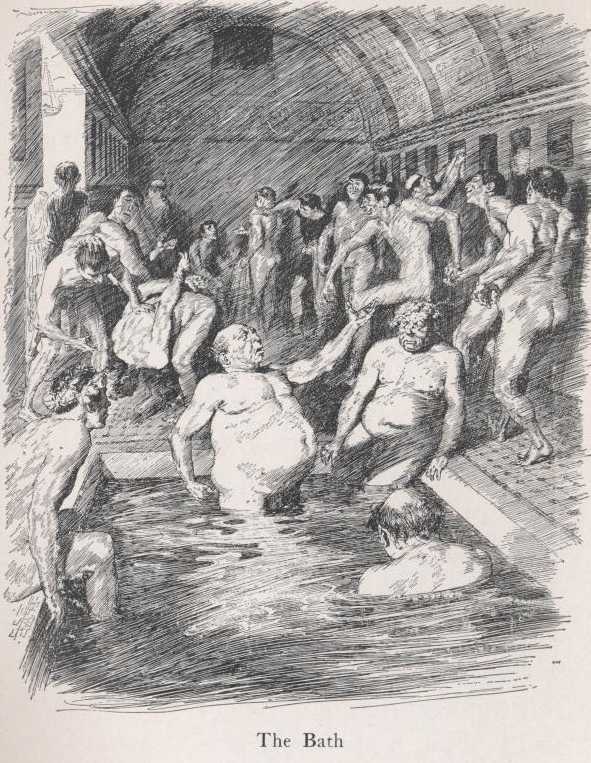

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-THIRD.

What were we miserable wretches to do, shut up in this newfangled

labyrinth. The idea of taking a hot bath had commenced to grow in favor,

so we finally asked the porter to lead us to the place and, throwing off

our clothing, which Giton spread out in the hall to dry, we went in. It

was very small, like a cold water cistern; Trimalchio was standing upright

in it, and one could not escape his disgusting bragging even here. He

declared that there was nothing nicer than bathing without a mob around,

and that a bakery had formerly occupied this very spot. Tired out at last,

he sat down, but when the echoes of the place tempted him, he lifted his

drunken mouth to the ceiling, and commenced murdering the songs of

Menacrates, at least that is what we were told by those who understood his

language. Some of the guests joined hands and ran around the edge of the

pool, making the place ring with their boisterous peals of laughter;

others tried to pick rings up from the floor, with their hands tied behind

them, or else, going down upon their knees, tried to touch the ends of

their toes by bending backwards. We went down into the pool while the rest

were taking part in such amusements. It was being heated for Trimalchio.

When the fumes of the wine had been dissipated, we were conducted into

another dining-room where Fortunata had laid out her own treasures; I

noticed, for instance, that there were little bronze fishermen upon the

lamps, the tables were of solid silver, the cups were porcelain inlaid

with gold; before our eyes wine was being strained through a straining

cloth. “One of my slaves shaves his first beard today,” Trimalchio

remarked, at length, “a promising, honest, thrifty lad; may he have no bad

luck, so let’s get our skins full and stick around till morning.”

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-FOURTH.

He had not ceased speaking when a cock crowed! Alarmed at this omen,

Trimalchio ordered wine thrown under the table and told them to sprinkle

the lamps with it; and he even went so far as to change his ring from his

left hand to his right. “That trumpeter did not sound off without a

reason,” he remarked; “there’s either a fire in the neighborhood, or else

someone’s going to give up the ghost. I hope it’s none of us! Whoever

brings that Jonah in shall have a present.” He had no sooner made this

promise, than a cock was brought in from somewhere in the neighborhood and

Trimalchio ordered the cook to prepare it for the pot. That same versatile

genius who had but a short time before made birds and fish out of a hog,

cut it up; it was then consigned to the kettle, and while Daedalus was

taking a long hot drink, Fortunata ground pepper in a boxwood mill. When

these delicacies had been consumed, Trimalchio looked the slaves over.

“You haven’t had anything to eat yet, have you?” he asked. “Get out and

let another relay come on duty.” Thereupon a second relay came in.

“Farewell, Gaius,” cried those going off duty, and “Hail, Gaius,” cried

those coming on. Our hilarity was somewhat dampened soon after, for a boy,

who was by no means bad looking, came in among the fresh slaves.

Trimalchio seized him and kissed him lingeringly, whereupon Fortunata,

asserting her rights in the house, began to rail at Trimalchio, styling

him an abomination who set no limits to his lechery, finally ending by

calling him a dog. Trimalchio flew into a rage at her abuse and threw a

wine cup at her head, whereupon she screeched, as if she had had an eye

knocked out and covered her face with her trembling hands. Scintilla was

frightened, too, and shielded the shuddering woman with her garment. An

officious slave presently held a cold water pitcher to her cheek and

Fortunata bent over it, sobbing and moaning. But as for Trimalchio, “What

the hell’s next?” he gritted out, “this Syrian dancing-whore don’t

remember anything! I took her off the auction block and made her a woman

among her equals, didn’t I? And here she puffs herself up like a frog and

pukes in her own nest; she’s a blockhead, all right, not a woman. But

that’s the way it is, if you’re born in an attic you can’t sleep in a

palace I’ll see that this booted Cassandra’s tamed, so help me my Genius,

I will! And I could have married ten million, even if I did only have two

cents: you know I’m not lying! ‘Let me give you a tip,’ said Agatho, the

perfumer to the lady next door, when he pulled me aside: ‘don’t let your

line die out!’ And here I’ve stuck the ax into my own leg because I was a

damned fool and didn’t want to seem fickle. I’ll see to it that you’re

more careful how you claw me up, sure as you’re born, I will! That you may

realize how seriously I take what you’ve done to me-- Habinnas, I don’t

want you to put her statue on my tomb for fear I’ll be nagged even after

I’m dead! And furthermore, that she may know I can repay a bad turn, I

won’t have her kissing me when I’m laid out!”

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-FIFTH.

When Trimalchio had launched this thunderbolt, Habinnas commenced to beg

him to control his anger. “There’s not one of us but goes wrong

sometimes,” argued he; “we’re not gods, we’re men.” Scintilla also cried

out through her tears, calling him “Gaius,” and entreating him by his

guardian angel to be mollified. Trimalchio could restrain the tears no

longer. “Habinnas,” he blubbered, “as you hope to enjoy your money, spit

in my face if I’ve done anything wrong. I kissed him because he’s very

thrifty, not because he’s a pretty boy. He can recite his division table

and read a book at sight: he bought himself a Thracian uniform from his

savings from his rations, and a stool and two dippers, with his own money,

too. He’s worth my attention, ain’t he? But Fortunata won’t see it! Ain’t

that the truth, you high-stepping hussy’? Let me beg you to make the best

of what you’ve got, you shekite, and don’t make me show my teeth, my

little darling, or you’ll find out what my temper’s like! Believe me, when

once I’ve made up my mind, I’m as fixed as a spike in a beam! But let’s

think of the living. I hope you’ll all make yourselves at home, gentlemen:

I was in your fix myself once; but rose to what I am now by my own merit.

It’s the brains that makes the man, all the rest’s bunk. I buy well, I

sell well, someone else will tell you a different story, but as for

myself, I’m fairly busting with prosperity. What, grunting-sow, still

bawling? I’ll see to it that you’ve something to bawl for, but as I

started to say, it was my thrift that brought me to my fortune. I was just

as tall as that candlestick when I came over from Asia; every day I used

to measure myself by it, and I would smear my lips with oil so my beard

would sprout all the sooner. I was my master’s ‘mistress’ for fourteen

years, for there’s nothing wrong in doing what your master orders, and I

satisfied my mistress, too, during that time, you know what I mean, but

I’ll say no more, for I’m not one of your braggarts!”

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-SIXTH.

“At last it came about by the will of the gods that I was master in the

house, and I had the real master under my thumb then. What is there left

to tell? I was made co-heir with Caesar and came into a Senator’s fortune.

But nobody’s ever satisfied with what he’s got, so I embarked in business.

I won’t keep you long in suspense; I built five ships and loaded them with

wine--worth its weight in gold, it was then--and sent them to Rome. You’d

think I’d ordered it so, for every last one of them foundered; it’s a

fact, no fairy tale about it, and Neptune swallowed thirty million

sesterces in one day! You don’t think I lost my pep, do you? By Hercules,

no! That was only an appetizer for me, just as if nothing at all had

happened. I built other and bigger ships, better found, too, so no one

could say I wasn’t game. A big ship’s a big venture, you know. I loaded

them up with wine again, bacon, beans, Capuan perfumes, and slaves:

Fortunata did the right thing in this affair, too, for she sold every

piece of jewelry and all her clothes into the bargain, and put a hundred

gold pieces in my hand. They were the nest-egg of my fortune. A thing’s

soon done when the gods will it; I cleared ten million sesterces by that

voyage, all velvet, and bought in all the estates that had belonged to my

patron, right away. I built myself a house and bought cattle to resell,

and whatever I touched grew just like a honeycomb. I chucked the game when

I got to have an income greater than all the revenues of my own country,

retired from business, and commenced to back freedmen. I never liked

business anyhow, as far as that goes, and was just about ready to quit

when an astrologer, a Greek fellow he was, and his name was Serapa,

happened to light in our colony, and he slipped me some information and

advised me to quit. He was hep to all the secrets of the gods: told me

things about myself that I’d forgotten, and explained everything to me

from needle and thread up; knew me inside out, he did, and only stopped

short of telling me what I’d had for dinner the day before. You’d have

thought he’d lived with me always!”

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-SEVENTH.

“Habinnas, you were there, I think, I’ll leave it to you; didn’t he

say--’You took your wife out of a whore-house’? you’re as lucky in your

friends, too, no one ever repays your favor with another, you own broad

estates, you nourish a viper under your wing, and--why shouldn’t I tell

it--I still have thirty years, four months, and two days to live! I’ll

also come into another bequest shortly. That’s what my horoscope tells me.

If I can extend my boundaries so as to join Apulia, I’ll think I’ve

amounted to something in this life! I built this house with Mercury on the

job, anyhow; it was a hovel, as you know, it’s a palace now! Four

dining-rooms, twenty bed-rooms, two marble colonnades, a store-room

upstairs, a bed-room where I sleep myself, a sitting-room for this viper,

a very good room for the porter, a guest-chamber for visitors. As a matter

of fact, Scaurus, when he was here, would stay nowhere else, although he

has a family place on the seashore. I’ll show you many other things, too,

in a jiffy; believe me, if you have an as, you’ll be rated at what you

have. So your humble servant, who was a frog, is now a king. Stychus,

bring out my funereal vestments while we wait, the ones I’ll be carried

out in, some perfume, too, and a draught of the wine in that jar, I mean

the kind I intend to have my bones washed in.”

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-EIGHTH.

It was not long before Stychus brought a white shroud and a

purple-bordered toga into the dining-room, and Trimalchio requested us to

feel them and see if they were pure wool. Then, with a smile, “Take care,

Stychus, that the mice don’t get at these things and gnaw them, or the

moths either. I’ll burn you alive if they do. I want to be carried out in

all my glory so all the people will wish me well.” Then, opening a jar of

nard, he had us all anointed. “I hope I’ll enjoy this as well when I’m

dead,” he remarked, “as I do while I’m alive.” He then ordered wine to be

poured into the punch-bowl. “Pretend,” said he, “that you’re invited to my

funeral feast.” The thing had grown positively nauseating, when

Trimalchio, beastly drunk by now, bethought himself of a new and singular

diversion and ordered some horn- blowers brought into the dining-room.

Then, propped up by many cushions, he stretched himself out upon the

couch. “Let on that I’m dead,” said he, “and say something nice about me.”

The horn-blowers sounded off a loud funeral march together, and one in

particular, a slave belonging to an undertaker, made such a fanfare that

he roused the whole neighborhood, and the watch, which was patrolling the

vicinity, thinking Trimalchio’s house was afire, suddenly smashed in the

door and rushed in with their water and axes, as is their right, raising a

rumpus all their own. We availed ourselves of this happy circumstance and,

leaving Agamemnon in the lurch, we took to our heels, as though we were

running away from a real conflagration.

VOLUME III.

FURTHER ADVENTURES OF ENCOLPIUS AND HIS COMPANIONS

CHAPTER THE SEVENTY-NINTH.

There was no torch to light the way for us, as we wandered around, nor did the silence of midnight give promise of our meeting any wayfarer with a light; in addition to this, we were drunk and unfamiliar with the district, which would confuse one, even in daylight, so for the best part of a mortal hour we dragged our bleeding feet over all the flints and pieces of broken tile, till we were extricated, at last, by Giton’s cleverness. This prudent youngster had been afraid of going astray on the day before, so he had taken care to mark all the pillars and columns with chalk. These marks stood out distinctly, even through the pitchy night, and by their brilliant whiteness pointed out the way for us as we wandered about. Nevertheless, we had no less cause for being in a sweat even when we came to our lodging, for the old woman herself had been sitting and swilling so long with her guests that even if one had set her afire, she would not have known it. We would have spent the night on the door-sill had not Trimalchio’s courier come up in state, with ten wagons; he hammered on the door for a short time, and then smashed it in, giving us an entrance through the same breach. (Hastening to the sleeping-chamber, I went to bed with my “brother” and, burning with passion as I was, after such a magnificent dinner, I surrendered myself wholly to sexual gratification.)

Oh Goddesses and Gods, that purple night

How soft the couch! And we, embracing tight;

With every wandering kiss our souls would meet!

Farewell all mortal woes, to die were sweet

But my self-congratulation was premature, for I was overcome with wine,

and when my unsteady hands relaxed their hold, Ascyltos, that

never-failing well-spring of iniquity, stole the boy away from me in the

night and carried him to his own bed, where he wallowed around without

restraint with a “brother” not his own, while the latter, not noticing the

fraud, or pretending not to notice it, went to sleep in a stranger’s arms,

in defiance of all human rights. Awaking at last, I felt the bed over and

found that it had been despoiled of its treasure: then, by all that lovers

hold dear, I swear I was on the verge of transfixing them both with my

sword and uniting their sleep with death. At last, however, I adopted a

more rational plan; I spanked Giton into wakefulness, and, glaring at

Ascyltos, “Since you have broken faith by this outrage,” I gritted out,

with a savage frown, “and severed our friendship, you had better get your

things together at once, and pick up some other bottom for your

abominations!” He raised no objection to this, but after we had divided

everything with scrupulous exactitude, “Come on now,” he demanded, “and

we’ll divide the boy!”

CHAPTER THE EIGHTIETH.

I thought this was a parting joke till he whipped out his sword, with a murderous hand. “You’ll not have this prize you’re brooding over, all to yourself! Since I’ve been rejected, I’ll have to cut off my share with this sword.” I followed suit, on my side, and, wrapping a mantle around my left arm, I put myself on guard for the duel. The unhappy boy, rendered desperate by our unreasoning fury, hugged each of us tightly by the knee, and in tears he humbly begged that this wretched lodging-house should not witness a Theban duel, and that we would not pollute--with mutual bloodshed the sacred rites of a friendship that was, as yet, unstained. “If a crime must be committed,” he wailed, “here is my naked throat, turn your swords this way and press home the points. I ought, to be the one to die, I broke the sacred pledge of friendship.” We lowered our points at these entreaties. “I’ll settle this dispute,” Ascyltos spoke up, “let the boy follow whomsoever he himself wishes to follow. In that way, he, at least, will have perfect freedom in choosing a ‘brother’.” Imagining that a relationship of such long standing had passed into a tie of blood, I was not at all uneasy, so I snatched at this proposition with precipitate eagerness, and submitted the dispute to the judge. He did not deliberate long enough to seem even to hesitate, for he got up and chose Ascyltos for a “brother,” as soon as the last syllable had passed my lips! At this decision I was thunder-struck, and threw myself upon the bed, unarmed and just as I stood. Had I not begrudged my enemy such a triumph, I would have laid violent hands upon myself. Flushed with success, Ascyltos marched out with his prize, and abandoned, in a strange town, a comrade in the depths of despair; one whom, but a little while before, he had loved most unselfishly, one whose destiny was so like his own.

As long as is expedient, the name of friendship lives,

Just as in dicing, Fortune smiles or lowers;

When good luck beckons, then your friend his gleeful service gives

But basely flies when ruin o’er you towers.

The strollers act their farces upon the stage, each one his part,

The father, son, the rich man, all are here,

But soon the page is turned upon the comic actor’s art,

The masque is dropped, the make-ups disappear!

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-FIRST.

Nevertheless, I did not indulge myself very long in tears, being afraid

that Menelaus, the tutor, might drop in upon me all alone in the

lodging-house, and catch me in the midst of my troubles, so I collected my

baggage and, with a heavy heart, sneaked off to an obscure quarter near

the seashore. There, I kept to my room for three days. My mind was

continually haunted by my loneliness and desertion, and I beat my breast,

already sore from blows. “Why could not the earth have opened and

swallowed me,” I wailed aloud, between the many deep-drawn groans, “or the

sea, which rages even against the guiltless? Did I flee from justice,

murder my ghost, and cheat the arena, in order that, after so many proofs

of courage, I might be left lying here deserted, a beggar and an exile, in

a lodging-house in a Greek town? And who condemned me to this desolation’?

A boy stained by every form of vice, who, by his own confession, ought to

be exiled: free, through vice, expert in vice, whose favors came through a

throw of the dice, who hired himself out as a girl to those who knew him

to be a boy! And as to the other, what about him? In place of the manly

toga, he donned the woman’s stola when he reached the age of puberty: he

resolved, even from his mother’s womb, never to become a man; in the

slave’s prison he took the woman’s part in the sexual act, he changed the

instrument of his lechery when he double-crossed me, abandoned the ties of

a long-standing friendship, and, shame upon him, sold everything for a

single night’s dalliance, like any other street-walker! Now the lovers lie

whole nights, locked in each other’s arms, and I suppose they make a

mockery of my desolation when they are resting up from the exhaustion

caused by their mutual excesses. But not with impunity! If I don’t avenge

the wrong they have done me. in their guilty blood, I’m no free man!”

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-SECOND.

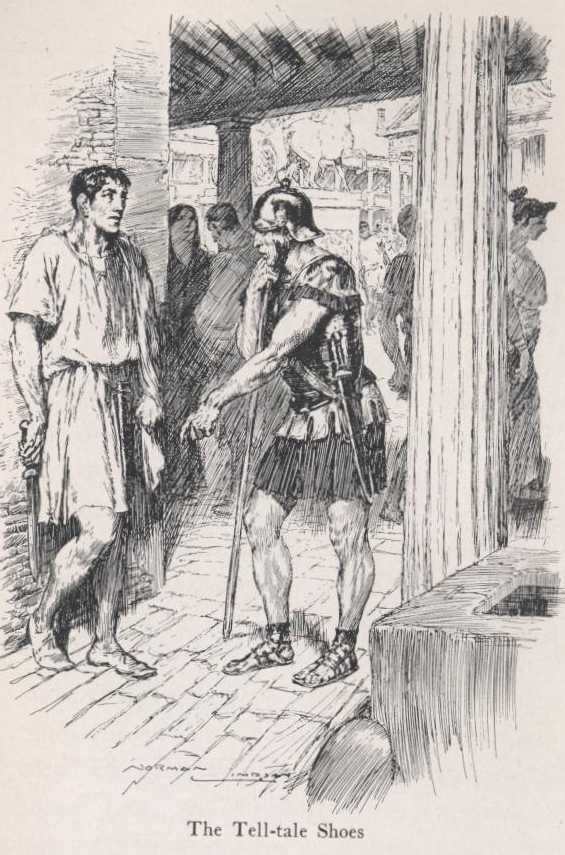

I girded on my sword, when I had said these words, and, fortifying my

strength with a heavy meal, so that weakness would not cause me to lose

the battle, I presently sallied forth into the public streets and rushed

through all the arcades, like a maniac. But while, with my face savagely

convulsed in a frown, I was meditating nothing but bloodshed and

slaughter, and was continually clapping my hand to the hilt of my sword,

which I had consecrated to this, I was observed by a soldier, that is, he

either was a real soldier, or else he was some night-prowling thug, who

challenged me. “Halt! Who goes there? What legion are you from? Who’s your

centurion?” “Since when have men in your outfit gone on pass in white

shoes?” he retorted, when I had lied stoutly about both centurion and

legion. Both my face and my confusion proved that I had been caught in a

lie, so he ordered me to surrender my arms and to take care that I did not

get into trouble. I was held up, as a matter of course, and, my revenge

balked, I returned to my lodging-house and, recovering by degrees from my

fright, I began to be grateful to the boldness of the footpad. It is not

wise to place much reliance upon any scheme, because Fortune has a method

of her own.

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-THIRD.

(Nevertheless, I found it very difficult to stifle my longing for revenge, and after tossing half the night in anxiety, I arose at dawn and, in the hope of mitigating my mental sufferings and of forgetting my wrongs, I took a walk through all the public arcades and) entered a picture-gallery, which contained a wonderful collection of pictures in various styles. I beheld works from the hand of Zeuxis, still undimmed by the passage of the years, and contemplated, not without a certain awe, the crude drawings of Protogenes, which equalled the reality of nature herself; but when I stood before the work of Apelles, the kind which the Greeks call “Monochromatic,” verily, I almost worshipped, for the outlines of the figures were drawn with such subtlety of touch, and were so life-like in their precision, that you would have thought their very souls were depicted. Here, an eagle was soaring into the sky bearing the shepherd of Mount Ida to heaven; there, the comely Hylas was struggling to escape from the embrace of the lascivious Naiad. Here, too, was Apollo, cursing his murderous hand and adorning his unstrung lyre with the flower just created. Standing among these lovers, which were only painted, “It seems that even the gods are wracked by love,” I cried aloud, as if I were in a wilderness. “Jupiter could find none to his taste, even in his own heaven, so he had to sin on earth, but no one was betrayed by him! The nymph who ravished Hylas would have controlled her passion had she thought Hercules was coming to forbid it. Apollo recalled the spirit of a boy in the form of a flower, and all the lovers of Fable enjoyed Love’s embraces without a rival, but I took as a comrade a friend more cruel than Lycurgus!” But at that very instant, as I was telling my troubles to the winds, a white-haired old man entered the picture-gallery; his face was care-worn, and he seemed, I know not why, to give promise of something great, although he bestowed so little care upon his dress that it was easily apparent that he belonged to that class of literati which the wealthy hold in contempt. “I am a poet,” he remarked, when he had approached me and stood at my side, “and one of no mean ability, I hope, that is, if anything is to be inferred from the crowns which gratitude can place even upon the heads of the unworthy! Then why, you demand, are you dressed so shabbily? For that very reason; love or art never yet made anyone rich.”

The trader trusts his fortune to the sea and takes his gains,

The warrior, for his deeds, is girt with gold;

The wily sycophant lies drunk on purple counterpanes,

Young wives must pay debauchees or they’re cold.

But solitary, shivering, in tatters Genius stands

Invoking a neglected art, for succor at its hands.

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-FOURTH.

“It is certainly true that a man is hated when he declares himself an

enemy to all vice, and begins to follow the right road in life, because,

in the first place, his habits are different from those of other people;

for who ever approved of anything to which he took exceptions? Then, they

whose only ambition is to pile up riches, don’t want to believe that men

can possess anything better than that which they have themselves;

therefore, they use every means in their power to so buffet the lovers of

literature that they will seem in their proper place--below the

moneybags.” “I know not why it should be so,” (I said with a sigh), “but

Poverty is the sister of Genius.” (“You have good reason,” the old man

replied, “to deplore the status of men of letters.” “No,” I answered,

“that was not the reason for my sigh, there is another and far weightier

cause for my grief.” Then, in accordance with the human propensity of

pouring one’s personal troubles into another’s ears, I explained my

misfortune to him, and dwelt particularly upon Ascyltos’ perfidy.) “Oh how

I wish that this enemy who is the cause of my enforced continence could be

mollified,” (I cried, with many a groan,) “but he is an old hand at

robbery, and more cunning than the pimps themselves!” (My frankness

pleased the old man, who attempted to comfort me and, to beguile my

sorrow, he related the particulars of an amorous intrigue in which he

himself had played a part.)

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-FIFTH.

“When I was attached to the Quaestor’s staff, in Asia, I was quartered

with a family at Pergamus. I found things very much to my liking there,

not only on account of the refined comfort of my apartments, but also

because of the extreme beauty of my host’s son. For the latter reason, I

had recourse to strategy, in order that the father should never suspect me

of being a seducer. So hotly would I flare up, whenever the abuse of

handsome boys was even mentioned at the table, and with such

uncompromising sternness would I protest against having my ears insulted

by such filthy talk, that I came to be looked upon, especially by the

mother, as one of the philosophers. I was conducting the lad to the

gymnasium before very long, and superintending his conduct, taking

especial care, all the while, that no one who could debauch him should

ever enter the house. Then there came a holiday, the school was closed,

and our festivities had rendered us too lazy to retire properly, so we lay

down in the dining-room. It was just about midnight, and I knew he was

awake, so I murmured this vow, in a very low voice, ‘Oh Lady Venus, could

I but kiss this lad, and he not know it, I would give him a pair of

turtle-doves tomorrow!’ On hearing the price offered for this favor, the

boy commenced to snore! Then, bending over the pretending sleeper, I

snatched a fleeting kiss or two. Satisfied with this beginning, I arose

early in the morning, brought a fine pair of turtle-doves to the eager

lad, and absolved myself from my vow.”

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-SIXTH.

“Next night, when the same opportunity presented itself, I changed my

petition, ‘If I can feel him all over with a wanton hand,’ I vowed, ‘and

he not know it, I will give him two of the gamest fighting-cocks, for his

silence.’ The lad nestled closer to me of his own accord, on hearing this

offer, and I truly believe that he was afraid that I was asleep. I made

short work of his apprehensions on that score, however, by stroking and

fondling his whole body. I worked myself into a passionate fervor that was

just short of supreme gratification. Then, when day dawned, I made him

happy with what I had promised him. When the third night gave me my

chance, I bent close to the ear of the rascal, who pretended to be asleep.

‘Immortal gods,’ I whispered, ‘if I can take full and complete

satisfaction of my love, from this sleeping beauty, I will tomorrow

present him with the best Macedonian pacer in the market, in return for

this bliss, provided that he does not know it.’ Never had the lad slept so

soundly! First I filled my hands with his snowy breasts, then I pressed a

clinging kiss upon his mouth, but I finally focused all my energies upon

one supreme delight! Early in the morning, he sat up in bed, awaiting my

usual gift. It is much easier to buy doves and game-cocks than it is to

buy a pacer, as you know, and aside from that, I was also afraid that so

valuable a present might render my motive subject to suspicion, so, after

strolling around for some hours, I returned to the house, and gave the lad

nothing at all except a kiss. He looked all around, threw his arms about

my neck. ‘Tell me, master,’ he cried, ‘where’s the pacer?’ (‘The

difficulty of getting one fine enough has compelled me to defer the

fulfillment of my promise,’ I replied, ‘but I will make it good in a few

days.’ The lad easily understood the true meaning of my answer, and his

countenance betrayed his secret resentment.)”

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-SEVENTH.

“(In the meantime,) by breaking this vow, I had cut myself off from the

avenue of access which I had contrived, but I returned to the attack, all

the same, when the opportunity came. In a few days, a similar occasion

brought about the very same conditions as before, and the instant I heard

his father snoring, I began pleading with the lad to receive me again into

his good graces, that is to say, that he ought to suffer me to satisfy

myself with him, and he in turn could do whatever his own distended member

desired. He was very angry, however, and would say nothing at all except,

‘Either you go to sleep, or I’ll call father!’ But no obstacle is so

difficult that depravity cannot twist around it and even while he

threatened ‘I’ll call father,’ I slipped into his bed and took my pleasure

in spite of his half-hearted resistance. Nor was he displeased with my

improper conduct for, although he complained for a while, that he had been

cheated and made a laughing- stock, and that his companions, to whom he

had bragged of his wealthy friend, had made sport of him. ‘But you’ll see

that I’ll not be like you,’ he whispered; ‘do it again, if you want to!’

All misunderstandings were forgotten and I was readmitted into the lad’s

good graces. Then I slipped off to sleep, after profiting by his

complaisance. But the youth, in the very flower of maturity, and just at

the best age for passive pleasure, was by no means satisfied with only one

repetition, so he roused me out of a heavy sleep. ‘Isn’t there something

you’d like to do?’ he whispered! The pastime had not begun to cloy, as

yet, and, somehow or other, what with panting and sweating and wriggling,

he got what he wanted and, worn out with pleasure, I dropped off to sleep

again. Less than an hour had passed when he began to punch me with his

hand. ‘Why are we not busy,’ he whispered! I flew into a violent rage at

being disturbed so many times, and threatened him in his own words,

‘Either you go to sleep, or I’ll call father!’”

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-EIGHTH.

Heartened up by this story, I began to draw upon his more comprehensive

knowledge as to the ages of the pictures and as to certain of the stories

connected with them, upon which I was not clear; and I likewise inquired

into the causes of the decadence of the present age, in which the most

refined arts had perished, and among them painting, which had not left

even the faintest trace of itself behind. “Greed of money,” he replied,

“has brought about these unaccountable changes. In the good old times,

when virtue was her own reward, the fine arts flourished, and there was

the keenest rivalry among men for fear that anything which could be of

benefit to future generations should remain long undiscovered. Then it was

that Democritus expressed the juices of all plants and spent his whole

life in experiments, in order that no curative property should lurk

unknown in stone or shrub. That he might understand the movements of

heaven and the stars, Eudoxus grew old upon the summit of a lofty

mountain: three times did Chrysippus purge his brain with hellebore, that

his faculties might be equal to invention. Turn to the sculptors if you

will; Lysippus perished from hunger while in profound meditation upon the

lines of a single statue, and Myron, who almost embodied the souls of men

and beasts in bronze, could not find an heir. And we, sodden with wine and

women, cannot even appreciate the arts already practiced, we only

criticise the past! We learn only vice, and teach it, too. What has become

of logic? of astronomy? Where is the exquisite road to wisdom? Who even

goes into a temple to make a vow, that he may achieve eloquence or bathe

in the fountain of wisdom? And they do not pray for good health and a

sound mind; before they even set foot upon the threshold of the temple,

one promises a gift if only he may bury a rich relative; another, if he

can but dig up a treasure, and still another, if he is permitted to amass

thirty millions of sesterces in safety! The Senate itself, the exponent of

all that should be right and just, is in the habit of promising a thousand

pounds of gold to the capitol, and that no one may question the propriety

of praying for money, it even decorates Jupiter himself with spoils’. Do

not hesitate, therefore, at expressing your surprise at the deterioration

of painting, since, by all the gods and men alike, a lump of gold is held

to be more beautiful than anything ever created by those crazy little

Greek fellows, Apelles and Phydias!”

CHAPTER THE EIGHTY-NINTH.

“But I see that your whole attention is held by that picture which portrays the destruction of Troy, so I will attempt to unfold the story in verse:

And now the tenth harvest beheld the beleaguered of Troia

Worn out with anxiety, fearing: the honor of Calchas

The prophet, hung wavering deep in the blackest despair.

Apollo commanded! The forested peaks of Mount Ida

Were felled and dragged down; the hewn timbers were fitted to fashion

A war-horse. Unfilled is a cavity left, and this cavern,

Roofed over, capacious enough for a camp. Here lie hidden

The raging impetuous valor of ten years of warfare.

Malignant Greek troops pack the recess, lurk in their own offering.

Alas my poor country! We thought that their thousand grim war-ships

Were beaten and scattered, our arable lands freed from warfare!

Th’ inscription cut into the horse, and the crafty behavior

Of Sinon, his mind ever powerful for evil, affirmed it.

Delivered from war, now the crowd, carefree, hastens to worship

And pours from the portals. Their cheeks wet with weeping, the joy

Of their tremulous souls brings to eyes tears which terror

Had banished. Laocoon, priest unto Neptune, with hair loosed,

An outcry evoked from the mob: he drew back his javelin

And launched it! The belly of wood was his target. The weapon

Recoiled, for the fates stayed his hand, and this artifice won us.

His feeble hand nerved he anew, and the lofty sides sounded,

His two-edged ax tried them severely. The young troops in ambush

Gasped. And as long as the reverberations re-echoed

The wooden mass breathed out a fear that was not of its own.

Imprisoned, the warriors advance to take Troia a captive

And finish the struggle by strategem new and unheard of.

Behold! Other portents: Where Tenedos steep breaks the ocean

Where great surging billows dash high; to be broken, and leap back

To form a deep hollow of calm, and resemble the plashing

Of oars, carried far through the silence of night, as when ships pass

And drive through the calm as it smashes against their fir bows.

Then backward we look: towards the rocks the tide carries two serpents

That coil and uncoil as they come, and their breasts, which are swollen

Aside dash the foam, as the bows of tall ships; and the ocean

Is lashed by their tails, their manes, free on the water, as savage

As even their eyes: now a blinding beam kindles the billows,

The sea with their hissing is sibilant! All stare in terror!

Laocoon’s twin sons in Phrygian raiment are standing

With priests wreathed for sacrifice. Them did the glistening serpents

Enfold in their coils! With their little hands shielding their faces,

The boys, neither thinking of self, but each one of his brother!

Fraternal love’s sacrifice! Death himself slew those poor children

By means of their unselfish fear for each other! The father,

A helper too feeble, now throws himself prone on their bodies:

The serpents, now glutted with death, coil around him and drag him

To earth! And the priest, at his altar a victim, lies beating

The ground. Thus the city of Troy, doomed to sack and destruction,

First lost her own gods by profaning their shrines and their worship.

The full moon now lifted her luminous beam and the small stars

Led forth, with her torch all ablaze; when the Greeks drew the bolts

And poured forth their warriors, on Priam’s sons, buried in darkness

And sodden with wine. First the leaders made trial of their weapons

Just as the horse, when unhitched from Thessalian neck-yoke,

First tosses his head and his mane, ere to pasture he rushes.

They draw their swords, brandish their shields and rush into the battle.

One slays the wine-drunken Trojans, prolonging their dreams

To death, which ends all. Still another takes brands from the altars,

And calls upon Troy’s sacred temples to fight against Trojans.”