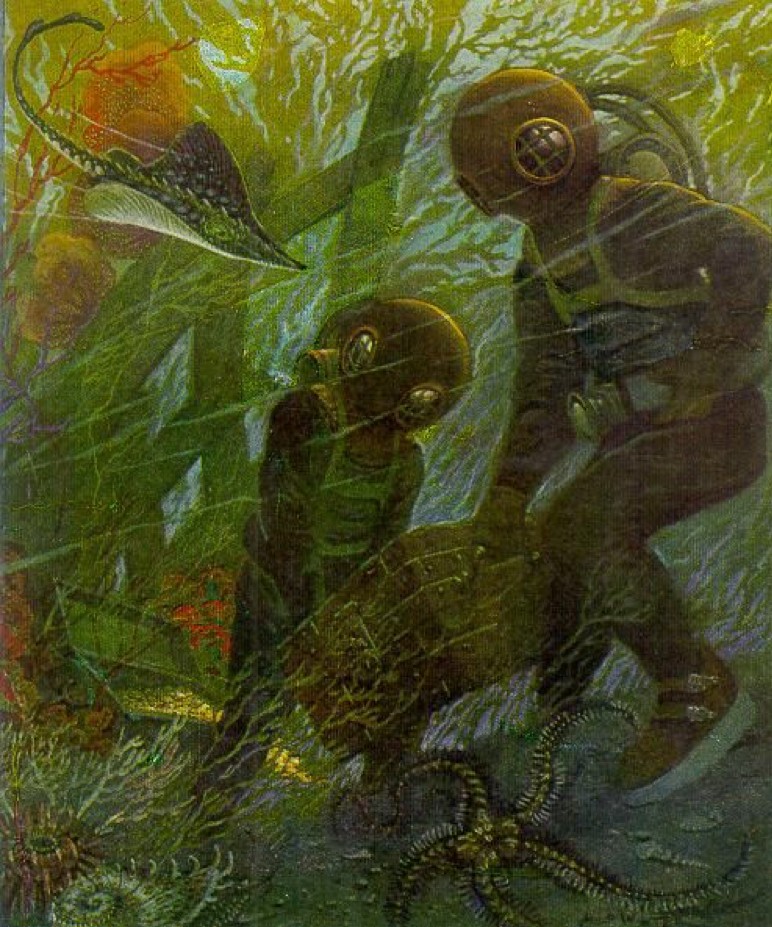

In the midst of the waters, a man appeared, a diver carrying a little leather bag at his belt. It was no corpse lost in the waves. It was a living man, swimming vigorously, sometimes disappearing to breathe at the surface, then instantly diving again.

I turned to Captain Nemo, and in an agitated voice:

“A man! A castaway!” I exclaimed. “We must rescue him at all cost!”

The captain didn’t reply but went to lean against the window.

The man drew near, and gluing his face to the panel, he stared at us.

To my deep astonishment, Captain Nemo gave him a signal. The diver answered with his hand, immediately swam up to the surface of the sea, and didn’t reappear.

“Don’t be alarmed,” the captain told me. “That’s Nicolas from Cape Matapan, nicknamed ‘Il Pesce.’* He’s well known throughout the Cyclades Islands. A bold diver! Water is his true element, and he lives in the sea more than on shore, going constantly from one island to another, even to Crete.”

*Italian: “The Fish.” Ed.

“You know him, captain?”

“Why not, Professor Aronnax?”

This said, Captain Nemo went to a cabinet standing near the lounge’s left panel. Next to this cabinet I saw a chest bound with hoops of iron, its lid bearing a copper plaque that displayed the Nautilus’s monogram with its motto Mobilis in Mobili.

Just then, ignoring my presence, the captain opened this cabinet, a sort of safe that contained a large number of ingots.

They were gold ingots. And they represented an enormous sum of money. Where had this precious metal come from? How had the captain amassed this gold, and what was he about to do with it?

I didn’t pronounce a word. I gaped. Captain Nemo took out the ingots one by one and arranged them methodically inside the chest, filling it to the top. At which point I estimate that it held more than 1,000 kilograms of gold, in other words, close to 5,000,000 francs.

After securely fastening the chest, Captain Nemo wrote an address on its lid in characters that must have been modern Greek.

This done, the captain pressed a button whose wiring was in communication with the crew’s quarters. Four men appeared and, not without difficulty, pushed the chest out of the lounge. Then I heard them hoist it up the iron companionway by means of pulleys.

Just then Captain Nemo turned to me:

“You were saying, professor?” he asked me.

“I wasn’t saying a thing, captain.”

“Then, sir, with your permission, I’ll bid you good evening.”

And with that, Captain Nemo left the lounge.

I reentered my stateroom, very puzzled, as you can imagine. I tried in vain to fall asleep. I kept searching for a relationship between the appearance of the diver and that chest filled with gold. Soon, from certain rolling and pitching movements, I sensed that the Nautilus had left the lower strata and was back on the surface of the water.

Then I heard the sound of footsteps on the platform. I realized that the skiff was being detached and launched to sea. For an instant it bumped the Nautilus’s side, then all sounds ceased.

Two hours later, the same noises, the same comings and goings, were repeated. Hoisted on board, the longboat was readjusted into its socket, and the Nautilus plunged back beneath the waves.

So those millions had been delivered to their address. At what spot on the continent? Who was the recipient of Captain Nemo’s gold?

The next day I related the night’s events to Conseil and the Canadian, events that had aroused my curiosity to a fever pitch. My companions were as startled as I was.

“But where does he get those millions?” Ned Land asked.

To this no reply was possible. After breakfast I made my way to the lounge and went about my work. I wrote up my notes until five o’clock in the afternoon. Just then—was it due to some personal indisposition?—I felt extremely hot and had to take off my jacket made of fan mussel fabric. A perplexing circumstance because we weren’t in the low latitudes, and besides, once the Nautilus was submerged, it shouldn’t be subject to any rise in temperature. I looked at the pressure gauge. It marked a depth of sixty feet, a depth beyond the reach of atmospheric heat.

I kept on working, but the temperature rose to the point of becoming unbearable.

“Could there be a fire on board?” I wondered.

I was about to leave the lounge when Captain Nemo entered. He approached the thermometer, consulted it, and turned to me:

“42 degrees centigrade,” he said.

“I’ve detected as much, captain,” I replied, “and if it gets even slightly hotter, we won’t be able to stand it.”

“Oh, professor, it won’t get any hotter unless we want it to!”

“You mean you can control this heat?”

“No, but I can back away from the fireplace producing it.”

“So it’s outside?”

“Surely. We’re cruising in a current of boiling water.”

“It can’t be!” I exclaimed.

“Look.”

The panels had opened, and I could see a completely white sea around the Nautilus. Steaming sulfurous fumes uncoiled in the midst of waves bubbling like water in a boiler. I leaned my hand against one of the windows, but the heat was so great, I had to snatch it back.

“Where are we?” I asked.

“Near the island of Santorini, professor,” the captain answered me, “and right in the channel that separates the volcanic islets of Nea Kameni and Palea Kameni. I wanted to offer you the unusual sight of an underwater eruption.”

“I thought,” I said, “that the formation of such new islands had come to an end.”

“Nothing ever comes to an end in these volcanic waterways,” Captain Nemo replied, “and thanks to its underground fires, our globe is continuously under construction in these regions. According to the Latin historians Cassiodorus and Pliny, by the year 19 of the Christian era, a new island, the divine Thera, had already appeared in the very place these islets have more recently formed. Then Thera sank under the waves, only to rise and sink once more in the year 69 A.D. From that day to this, such plutonic construction work has been in abeyance. But on February 3, 1866, a new islet named George Island emerged in the midst of sulfurous steam near Nea Kameni and was fused to it on the 6th of the same month. Seven days later, on February 13, the islet of Aphroessa appeared, leaving a ten-meter channel between itself and Nea Kameni. I was in these seas when that phenomenon occurred and I was able to observe its every phase. The islet of Aphroessa was circular in shape, measuring 300 feet in diameter and thirty feet in height. It was made of black, glassy lava mixed with bits of feldspar. Finally, on March 10, a smaller islet called Reka appeared next to Nea Kameni, and since then, these three islets have fused to form one single, selfsame island.”

“What about this channel we’re in right now?” I asked.

“Here it is,” Captain Nemo replied, showing me a chart of the Greek Islands. “You observe that I’ve entered the new islets in their place.”

“But will this channel fill up one day?”

“Very likely, Professor Aronnax, because since 1866 eight little lava islets have surged up in front of the port of St. Nicolas on Palea Kameni. So it’s obvious that Nea and Palea will join in days to come. In the middle of the Pacific, tiny infusoria build continents, but here they’re built by volcanic phenomena. Look, sir! Look at the construction work going on under these waves.”

I returned to the window. The Nautilus was no longer moving. The heat had become unbearable. From the white it had recently been, the sea was turning red, a coloration caused by the presence of iron salts. Although the lounge was hermetically sealed, it was filling with an intolerable stink of sulfur, and I could see scarlet flames of such brightness, they overpowered our electric light.

I was swimming in perspiration, I was stifling, I was about to be cooked. Yes, I felt myself cooking in actual fact!

“We can’t stay any longer in this boiling water,” I told the captain.

“No, it wouldn’t be advisable,” replied Nemo the Emotionless.

He gave an order. The Nautilus tacked about and retreated from this furnace it couldn’t brave with impunity. A quarter of an hour later, we were breathing fresh air on the surface of the waves.

It then occurred to me that if Ned had chosen these waterways for our escape attempt, we wouldn’t have come out alive from this sea of fire.

The next day, February 16, we left this basin, which tallies depths of 3,000 meters between Rhodes and Alexandria, and passing well out from Cerigo Island after doubling Cape Matapan, the Nautilus left the Greek Islands behind.

CHAPTER 7

The Mediterranean in Forty-Eight Hours

THE MEDITERRANEAN, your ideal blue sea: to Greeks simply “the sea,” to Hebrews “the great sea,” to Romans mare nostrum.* Bordered by orange trees, aloes, cactus, and maritime pine trees, perfumed with the scent of myrtle, framed by rugged mountains, saturated with clean, transparent air but continuously under construction by fires in the earth, this sea is a genuine battlefield where Neptune and Pluto still struggle for world domination. Here on these beaches and waters, says the French historian Michelet, a man is revived by one of the most invigorating climates in the world.

*Latin: “our sea.” Ed.

But as beautiful as it was, I could get only a quick look at this basin whose surface area comprises 2,000,000 square kilometers. Even Captain Nemo’s personal insights were denied me, because that mystifying individual didn’t appear one single time during our high-speed crossing. I estimate that the Nautilus covered a track of some 600 leagues under the waves of this sea, and this voyage was accomplished in just twenty-four hours times two. Departing from the waterways of Greece on the morning of February 16, we cleared the Strait of Gibraltar by sunrise on the 18th.

It was obvious to me that this Mediterranean, pinned in the middle of those shores he wanted to avoid, gave Captain Nemo no pleasure. Its waves and breezes brought back too many memories, if not too many regrets. Here he no longer had the ease of movement and freedom of maneuver that the oceans allowed him, and his Nautilus felt cramped so close to the coasts of both Africa and Europe.

Accordingly, our speed was twenty-five miles (that is, twelve four-kilometer leagues) per hour. Needless to say, Ned Land had to give up his escape plans, much to his distress. Swept along at the rate of twelve to thirteen meters per second, he could hardly make use of the skiff. Leaving the Nautilus under these conditions would have been like jumping off a train racing at this speed, a rash move if there ever was one. Moreover, to renew our air supply, the submersible rose to the surface of the waves only at night, and relying solely on compass and log, it steered by dead reckoning.

Inside the Mediterranean, then, I could catch no more of its fast-passing scenery than a traveler might see from an express train; in other words, I could view only the distant horizons because the foregrounds flashed by like lightning. But Conseil and I were able to observe those Mediterranean fish whose powerful fins kept pace for a while in the Nautilus’s waters. We stayed on watch before the lounge windows, and our notes enable me to reconstruct, in a few words, the ichthyology of this sea.

Among the various fish inhabiting it, some I viewed, others I glimpsed, and the rest I missed completely because of the Nautilus’s speed. Kindly allow me to sort them out using this whimsical system of classification. It will at least convey the quickness of my observations.

In the midst of the watery mass, brightly lit by our electric beams, there snaked past those one-meter lampreys that are common to nearly every clime. A type of ray from the genus Oxyrhynchus, five feet wide, had a white belly with a spotted, ash-gray back and was carried along by the currents like a huge, wide-open shawl. Other rays passed by so quickly I couldn’t tell if they deserved that name “eagle ray” coined by the ancient Greeks, or those designations of “rat ray,” “bat ray,” and “toad ray” that modern fishermen have inflicted on them. Dogfish known as topes, twelve feet long and especially feared by divers, were racing with each other. Looking like big bluish shadows, thresher sharks went by, eight feet long and gifted with an extremely acute sense of smell. Dorados from the genus Sparus, some measuring up to thirteen decimeters, appeared in silver and azure costumes encircled with ribbons, which contrasted with the dark color of their fins; fish sacred to the goddess Venus, their eyes set in brows of gold; a valuable species that patronizes all waters fresh or salt, equally at home in rivers, lakes, and oceans, living in every clime, tolerating any temperature, their line dating back to prehistoric times on this earth yet preserving all its beauty from those far-off days. Magnificent sturgeons, nine to ten meters long and extremely fast, banged their powerful tails against the glass of our panels, showing bluish backs with small brown spots; they resemble sharks, without equaling their strength, and are encountered in every sea; in the spring they delight in swimming up the great rivers, fighting the currents of the Volga, Danube, Po, Rhine, Loire, and Oder, while feeding on herring, mackerel, salmon, and codfish; although they belong to the class of cartilaginous fish, they rate as a delicacy; they’re eaten fresh, dried, marinated, or salt-preserved, and in olden times they were borne in triumph to the table of the Roman epicure Lucullus.

But whenever the Nautilus drew near the surface, those denizens of the Mediterranean I could observe most productively belonged to the sixty-third genus of bony fish. These were tuna from the genus Scomber, blue-black on top, silver on the belly armor, their dorsal stripes giving off a golden gleam. They are said to follow ships in search of refreshing shade from the hot tropical sun, and they did just that with the Nautilus, as they had once done with the vessels of the Count de La Pérouse. For long hours they competed in speed with our submersible. I couldn’t stop marveling at these animals so perfectly cut out for racing, their heads small, their bodies sleek, spindle-shaped, and in some cases over three meters long, their pectoral fins gifted with remarkable strength, their caudal fins forked. Like certain flocks of birds, whose speed they equal, these tuna swim in triangle formation, which prompted the ancients to say they’d boned up on geometry and military strategy. And yet they can’t escape the Provençal fishermen, who prize them as highly as did the ancient inhabitants of Turkey and Italy; and these valuable animals, as oblivious as if they were deaf and blind, leap right into the Marseilles tuna nets and perish by the thousands.

Just for the record, I’ll mention those Mediterranean fish that Conseil and I barely glimpsed. There were whitish eels of the species Gymnotus fasciatus that passed like elusive wisps of steam, conger eels three to four meters long that were tricked out in green, blue, and yellow, three-foot hake with a liver that makes a dainty morsel, wormfish drifting like thin seaweed, sea robins that poets call lyrefish and seamen pipers and whose snouts have two jagged triangular plates shaped like old Homer’s lyre, swallowfish swimming as fast as the bird they’re named after, redheaded groupers whose dorsal fins are trimmed with filaments, some shad (spotted with black, gray, brown, blue, yellow, and green) that actually respond to tinkling handbells, splendid diamond-shaped turbot that were like aquatic pheasants with yellowish fins stippled in brown and the left topside mostly marbled in brown and yellow, finally schools of wonderful red mullet, real oceanic birds of paradise that ancient Romans bought for as much as 10,000 sesterces apiece, and which they killed at the table, so they could heartlessly watch it change color from cinnabar red when alive to pallid white when dead.

And as for other fish common to the Atlantic and Mediterranean, I was unable to observe miralets, triggerfish, puffers, seahorses, jewelfish, trumpetfish, blennies, gray mullet, wrasse, smelt, flying fish, anchovies, sea bream, porgies, garfish, or any of the chief representatives of the order Pleuronecta, such as sole, flounder, plaice, dab, and brill, simply because of the dizzying speed with which the Nautilus hustled through these opulent waters.

As for marine mammals, on passing by the mouth of the Adriatic Sea, I thought I recognized two or three sperm whales equipped with the single dorsal fin denoting the genus Physeter, some pilot whales from the genus Globicephalus exclusive to the Mediterranean, the forepart of the head striped with small distinct lines, and also a dozen seals with white bellies and black coats, known by the name monk seals and just as solemn as if they were three-meter Dominicans.

For his part, Conseil thought he spotted a turtle six feet wide and adorned with three protruding ridges that ran lengthwise. I was sorry to miss this reptile, because from Conseil’s description, I believe I recognized the leatherback turtle, a pretty rare species. For my part, I noted only some loggerhead turtles with long carapaces.

As for zoophytes, for a few moments I was able to marvel at a wonderful, orange-hued hydra from the genus Galeolaria that clung to the glass of our port panel; it consisted of a long, lean filament that spread out into countless branches and ended in the most delicate lace ever spun by the followers of Arachne. Unfortunately I couldn’t fish up this wonderful specimen, and surely no other Mediterranean zoophytes would have been offered to my gaze, if, on the evening of the 16th, the Nautilus hadn’t slowed down in an odd fashion. This was the situation.

By then we were passing between Sicily and the coast of Tunisia. In the cramped space between Cape Bon and the Strait of Messina, the sea bottom rises almost all at once. It forms an actual ridge with only seventeen meters of water remaining above it, while the depth on either side is 170 meters. Consequently, the Nautilus had to maneuver with caution so as not to bump into this underwater barrier.

I showed Conseil the position of this long reef on our chart of the Mediterranean.

“But with all due respect to master,” Conseil ventured to observe, “it’s like an actual isthmus connecting Europe to Africa.”

“Yes, my boy,” I replied, “it cuts across the whole Strait of Sicily, and Smith’s soundings prove that in the past, these two continents were genuinely connected between Cape Boeo and Cape Farina.”

“I can easily believe it,” Conseil said.

“I might add,” I went on, “that there’s a similar barrier between Gibraltar and Ceuta, and in prehistoric times it closed off the Mediterranean completely.”

“Gracious!” Conseil put in. “Suppose one day some volcanic upheaval raises these two barriers back above the waves!”

“That’s most unlikely, Conseil.”

“If master will allow me to finish, I mean that if this phenomenon occurs, it might prove distressing to Mr. de Lesseps, who has gone to such pains to cut through his isthmus!”

“Agreed, but I repeat, Conseil: such a phenomenon won’t occur. The intensity of these underground forces continues to diminish. Volcanoes were quite numerous in the world’s early days, but they’re going extinct one by one; the heat inside the earth is growing weaker, the temperature in the globe’s lower strata is cooling appreciably every century, and to our globe’s detriment, because its heat is its life.”

“But the sun—”

“The sun isn’t enough, Conseil. Can it restore heat to a corpse?”

“Not that I’ve heard.”

“Well, my friend, someday the earth will be just such a cold corpse. Like the moon, which long ago lost its vital heat, our globe will become lifeless and unlivable.”

“In how many centuries?” Conseil asked.

“In hundreds of thousands of years, my boy.”

“Then we have ample time to finish our voyage,” Conseil replied, “if Ned Land doesn’t mess things up!”

Thus reassured, Conseil went back to studying the shallows that the Nautilus was skimming at moderate speed.

On the rocky, volcanic seafloor, there bloomed quite a collection of moving flora: sponges, sea cucumbers, jellyfish called sea gooseberries that were adorned with reddish tendrils and gave off a subtle phosphorescence, members of the genus Beroe that are commonly known by the name melon jellyfish and are bathed in the shimmer of the whole solar spectrum, free-swimming crinoids one meter wide that reddened the waters with their crimson hue, treelike basket stars of the greatest beauty, sea fans from the genus Pavonacea with long stems, numerous edible sea urchins of various species, plus green sea anemones with a grayish trunk and a brown disk lost beneath the olive-colored tresses of their tentacles.

Conseil kept especially busy observing mollusks and articulates, and although his catalog is a little dry, I wouldn’t want to wrong the gallant lad by leaving out his personal observations.

From the branch Mollusca, he mentions numerous comb-shaped scallops, hooflike spiny oysters piled on top of each other, triangular coquina, three-pronged glass snails with yellow fins and transparent shells, orange snails from the genus Pleurobranchus that looked like eggs spotted or speckled with greenish dots, members of the genus Aplysia also known by the name sea hares, other sea hares from the genus Dolabella, plump paper-bubble shells, umbrella shells exclusive to the Mediterranean, abalone whose shell produces a mother-of-pearl much in demand, pilgrim scallops, saddle shells that diners in the French province of Languedoc are said to like better than oysters, some of those cockleshells so dear to the citizens of Marseilles, fat white venus shells that are among the clams so abundant off the coasts of North America and eaten in such quantities by New Yorkers, variously colored comb shells with gill covers, burrowing date mussels with a peppery flavor I relish, furrowed heart cockles whose shells have riblike ridges on their arching summits, triton shells pocked with scarlet bumps, carniaira snails with backward-curving tips that make them resemble flimsy gondolas, crowned ferola snails, atlanta snails with spiral shells, gray nudibranchs from the genus Tethys that were spotted with white and covered by fringed mantles, nudibranchs from the suborder Eolidea that looked like small slugs, sea butterflies crawling on their backs, seashells from the genus Auricula including the oval-shaped Auricula myosotis, tan wentletrap snails, common periwinkles, violet snails, cineraira snails, rock borers, ear shells, cabochon snails, pandora shells, etc.

As for the articulates, in his notes Conseil has very appropriately divided them into six classes, three of which belong to the marine world. These classes are the Crustacea, Cirripedia, and Annelida.

Crustaceans are subdivided into nine orders, and the first of these consists of the decapods, in other words, animals whose head and thorax are usually fused, whose cheek-and-mouth mechanism is made up of several pairs of appendages, and whose thorax has four, five, or six pairs of walking legs. Conseil used the methods of our mentor Professor Milne-Edwards, who puts the decapods in three divisions: Brachyura, Macrura, and Anomura. These names may look a tad fierce, but they’re accurate and appropriate. Among the Brachyura, Conseil mentions some amanthia crabs whose fronts were armed with two big diverging tips, those inachus scorpions that—lord knows why—symbolized wisdom to the ancient Greeks, spider crabs of the massena and spinimane varieties that had probably gone astray in these shallows because they usually live in the lower depths, xanthid crabs, pilumna crabs, rhomboid crabs, granular box crabs (easy on the digestion, as Conseil ventured to observe), toothless masked crabs, ebalia crabs, cymopolia crabs, woolly-handed crabs, etc. Among the Macrura (which are subdivided into five families: hardshells, burrowers, crayfish, prawns, and ghost crabs) Conseil mentions some common spiny lobsters whose females supply a meat highly prized, slipper lobsters or common shrimp, waterside gebia shrimp, and all sorts of edible species, but he says nothing of the crayfish subdivision that includes the true lobster, because spiny lobsters are the only type in the Mediterranean. Finally, among the Anomura, he saw common drocina crabs dwelling inside whatever abandoned seashells they could take over, homola crabs with spiny fronts, hermit crabs, hairy porcelain crabs, etc.

There Conseil’s work came to a halt. He didn’t have time to finish off the class Crustacea through an examination of its stomatopods, amphipods, homopods, isopods, trilobites, branchiopods, ostracods, and entomostraceans. And in order to complete his study of marine articulates, he needed to mention the class Cirripedia, which contains water fleas and carp lice, plus the class Annelida, which he would have divided without fail into tubifex worms and dorsibranchian worms. But having gone past the shallows of the Strait of Sicily, the Nautilus resumed its usual deep-water speed. From then on, no more mollusks, no more zoophytes, no more articulates. Just a few large fish sweeping by like shadows.

During the night of February 16-17, we entered the second Mediterranean basin, whose maximum depth we found at 3,000 meters. The Nautilus, driven downward by its propeller and slanting fins, descended to the lowest strata of this sea.

There, in place of natural wonders, the watery mass offered some thrilling and dreadful scenes to my eyes. In essence, we were then crossing that part of the whole Mediterranean so fertile in casualties. From the coast of Algiers to the beaches of Provence, how many ships have wrecked, how many vessels have vanished! Compared to the vast liquid plains of the Pacific, the Mediterranean is a mere lake, but it’s an unpredictable lake with fickle waves, today kindly and affectionate to those frail single-masters drifting between a double ultramarine of sky and water, tomorrow bad-tempered and turbulent, agitated by the winds, demolishing the strongest ships beneath sudden waves that smash down with a headlong wallop.

So, in our swift cruise through these deep strata, how many vessels I saw lying on the seafloor, some already caked with coral, others clad only in a layer of rust, plus anchors, cannons, shells, iron fittings, propeller blades, parts of engines, cracked cylinders, staved-in boilers, then hulls floating in midwater, here upright, there overturned.

Some of these wrecked ships had perished in collisions, others from hitting granite reefs. I saw a few that had sunk straight down, their masting still upright, their rigging stiffened by the water. They looked like they were at anchor by some immense, open, offshore mooring where they were waiting for their departure time. When the Nautilus passed between them, covering them with sheets of electricity, they seemed ready to salute us with their colors and send us their serial numbers! But no, nothing but silence and death filled this field of catastrophes!

I observed that these Mediterranean depths became more and more cluttered with such gruesome wreckage as the Nautilus drew nearer to the Strait of Gibraltar. By then the shores of Africa and Europe were converging, and in this narrow space collisions were commonplace. There I saw numerous iron undersides, the phantasmagoric ruins of steamers, some lying down, others rearing up like fearsome animals. One of these boats made a dreadful first impression: sides torn open, funnel bent, paddle wheels stripped to the mountings, rudder separated from the sternpost and still hanging from an iron chain, the board on its stern eaten away by marine salts! How many lives were dashed in this shipwreck! How many victims were swept under the waves! Had some sailor on board lived to tell the story of this dreadful disaster, or do the waves still keep this casualty a secret? It occurred to me, lord knows why, that this boat buried under the sea might have been the Atlas, lost with all hands some twenty years ago and never heard from again! Oh, what a gruesome tale these Mediterranean depths could tell, this huge boneyard where so much wealth has been lost, where so many victims have met their deaths!

Meanwhile, briskly unconcerned, the Nautilus ran at full propeller through the midst of these ruins. On February 18, near three o’clock in the morning, it hove before the entrance to the Strait of Gibraltar.

There are two currents here: an upper current, long known to exist, that carries the ocean’s waters into the Mediterranean basin; then a lower countercurrent, the only present-day proof of its existence being logic. In essence, the Mediterranean receives a continual influx of water not only from the Atlantic but from rivers emptying into it; since local evaporation isn’t enough to restore the balance, the total amount of added water should make this sea’s level higher every year. Yet this isn’t the case, and we’re naturally forced to believe in the existence of some lower current that carries the Mediterranean’s surplus through the Strait of Gibraltar and into the Atlantic basin.

And so it turned out. The Nautilus took full advantage of this countercurrent. It advanced swiftly through this narrow passageway. For an instant I could glimpse the wonderful ruins of the Temple of Hercules, buried undersea, as Pliny and Avianus have mentioned, together with the flat island they stand on; and a few minutes later, we were floating on the waves of the Atlantic.

CHAPTER 8

The Bay of Vigo

THE ATLANTIC! A vast expanse of water whose surface area is 25,000,000 square miles, with a length of 9,000 miles and an average width of 2,700. A major sea nearly unknown to the ancients, except perhaps the Carthaginians, those Dutchmen of antiquity who went along the west coasts of Europe and Africa on their commercial junkets! An ocean whose parallel winding shores form an immense perimeter fed by the world’s greatest rivers: the St. Lawrence, Mississippi, Amazon, Plata, Orinoco, Niger, Senegal, Elbe, Loire, and Rhine, which bring it waters from the most civilized countries as well as the most undeveloped areas! A magnificent plain of waves plowed continuously by ships of every nation, shaded by every flag in the world, and ending in those two dreadful headlands so feared by navigators, Cape Horn and the Cape of Tempests!

The Nautilus broke these waters with the edge of its spur after doing nearly 10,000 leagues in three and a half months, a track longer than a great circle of the earth. Where were we heading now, and what did the future have in store for us?

Emerging from the Strait of Gibraltar, the Nautilus took to the high seas. It returned to the surface of the waves, so our daily strolls on the platform were restored to us.

I climbed onto it instantly, Ned Land and Conseil along with me. Twelve miles away, Cape St. Vincent was hazily visible, the southwestern tip of the Hispanic peninsula. The wind was blowing a pretty strong gust from the south. The sea was swelling and surging. Its waves made the Nautilus roll and jerk violently. It was nearly impossible to stand up on the platform, which was continuously buffeted by this enormously heavy sea. After inhaling a few breaths of air, we went below once more.

I repaired to my stateroom. Conseil returned to his cabin; but the Canadian, looking rather worried, followed me. Our quick trip through the Mediterranean hadn’t allowed him to put his plans into execution, and he could barely conceal his disappointment.

After the door to my stateroom was closed, he sat and stared at me silently.

“Ned my friend,” I told him, “I know how you feel, but you mustn’t blame yourself. Given the way the Nautilus was navigating, it would have been sheer insanity to think of escaping!”

Ned Land didn’t reply. His pursed lips and frowning brow indicated that he was in the grip of his monomania.

“Look here,” I went on, “as yet there’s no cause for despair. We’re going up the coast of Portugal. France and England aren’t far off, and there we’ll easily find refuge. Oh, I grant you, if the Nautilus had emerged from the Strait of Gibraltar and made for that cape in the south, if it were taking us toward those regions that have no continents, then I’d share your alarm. But we now know that Captain Nemo doesn’t avoid the seas of civilization, and in a few days I think we can safely take action.”

Ned Land stared at me still more intently and finally unpursed his lips:

“We’ll do it this evening,” he said.

I straightened suddenly. I admit that I was less than ready for this announcement. I wanted to reply to the Canadian, but words failed me.

“We agreed to wait for the right circumstances,” Ned Land went on. “Now we’ve got those circumstances. This evening we’ll be just a few miles off the coast of Spain. It’ll be cloudy tonight. The wind’s blowing toward shore. You gave me your promise, Professor Aronnax, and I’m counting on you.”

Since I didn’t say anything, the Canadian stood up and approached me:

“We’ll do it this evening at nine o’clock,” he said. “I’ve alerted Conseil. By that time Captain Nemo will be locked in his room and probably in bed. Neither the mechanics or the crewmen will be able to see us. Conseil and I will go to the central companionway. As for you, Professor Aronnax, you’ll stay in the library two steps away and wait for my signal. The oars, mast, and sail are in the skiff. I’ve even managed to stow some provisions inside. I’ve gotten hold of a monkey wrench to unscrew the nuts bolting the skiff to the Nautilus’s hull. So everything’s ready. I’ll see you this evening.”

“The sea is rough,” I said.

“Admitted,” the Canadian replied, “but we’ve got to risk it. Freedom is worth paying for. Besides, the longboat’s solidly built, and a few miles with the wind behind us is no big deal. By tomorrow, who knows if this ship won’t be 100 leagues out to sea? If circumstances are in our favor, between ten and eleven this evening we’ll be landing on some piece of solid ground, or we’ll be dead. So we’re in God’s hands, and I’ll see you this evening!”

This said, the Canadian withdrew, leaving me close to dumbfounded. I had imagined that if it came to this, I would have time to think about it, to talk it over. My stubborn companion hadn’t granted me this courtesy. But after all, what would I have said to him? Ned Land was right a hundred times over. These were near-ideal circumstances, and he was taking full advantage of them. In my selfish personal interests, could I go back on my word and be responsible for ruining the future lives of my companions? Tomorrow, might not Captain Nemo take us far away from any shore?

Just then a fairly loud hissing told me that the ballast tanks were filling, and the Nautilus sank beneath the waves of the Atlantic.

I stayed in my stateroom. I wanted to avoid the captain, to hide from his eyes the agitation overwhelming me. What an agonizing day I spent, torn between my desire to regain my free will and my regret at abandoning this marvelous Nautilus, leaving my underwater research incomplete! How could I relinquish this ocean—“my own Atlantic,” as I liked to call it—without observing its lower strata, without wresting from it the kinds of secrets that had been revealed to me by the seas of the East Indies and the Pacific! I was putting down my novel half read, I was waking up as my dream neared its climax! How painfully the hours passed, as I sometimes envisioned myself safe on shore with my companions, or, despite my better judgment, as I sometimes wished that some unforeseen circumstances would prevent Ned Land from carrying out his plans.

Twice I went to the lounge. I wanted to consult the compass. I wanted to see if the Nautilus’s heading was actually taking us closer to the coast or spiriting us farther away. But no. The Nautilus was still in Portuguese waters. Heading north, it was cruising along the ocean’s beaches.

So I had to resign myself to my fate and get ready to escape. My baggage wasn’t heavy. My notes, nothing more.

As for Captain Nemo, I wondered what he would make of our escaping, what concern or perhaps what distress it might cause him, and what he would do in the twofold event of our attempt either failing or being found out! Certainly I had no complaints to register with him, on the contrary. Never was hospitality more wholehearted than his. Yet in leaving him I couldn’t be accused of ingratitude. No solemn promises bound us to him. In order to keep us captive, he had counted only on the force of circumstances and not on our word of honor. But his avowed intention to imprison us forever on his ship justified our every effort.

I hadn’t seen the captain since our visit to the island of Santorini. Would fate bring me into his presence before our departure? I both desired and dreaded it. I listened for footsteps in the stateroom adjoining mine. Not a sound reached my ear. His stateroom had to be deserted.

Then I began to wonder if this eccentric individual was even on board. Since that night when the skiff had left the Nautilus on some mysterious mission, my ideas about him had subtly changed. In spite of everything, I thought that Captain Nemo must have kept up some type of relationship with the shore. Did he himself never leave the Nautilus? Whole weeks had often gone by without my encountering him. What was he doing all the while? During all those times I’d thought he was convalescing in the grip of some misanthropic fit, was he instead far away from the ship, involved in some secret activity whose nature still eluded me?

All these ideas and a thousand others assaulted me at the same time. In these strange circumstances the scope for conjecture was unlimited. I felt an unbearable queasiness. This day of waiting seemed endless. The hours struck too slowly to keep up with my impatience.

As usual, dinner was served me in my stateroom. Full of anxiety, I ate little. I left the table at seven o’clock. 120 minutes—I was keeping track of them—still separated me from the moment I was to rejoin Ned Land. My agitation increased. My pulse was throbbing violently. I couldn’t stand still. I walked up and down, hoping to calm my troubled mind with movement. The possibility of perishing in our reckless undertaking was the least of my worries; my heart was pounding at the thought that our plans might be discovered before we had left the Nautilus, at the thought of being hauled in front of Captain Nemo and finding him angered, or worse, saddened by my deserting him.

I wanted to see the lounge one last time. I went down the gangways and arrived at the museum where I had spent so many pleasant and productive hours. I stared at all its wealth, all its treasures, like a man on the eve of his eternal exile, a man departing to return no more. For so many days now, these natural wonders and artistic masterworks had been central to my life, and I was about to leave them behind forever. I wanted to plunge my eyes through the lounge window and into these Atlantic waters; but the panels were hermetically sealed, and a mantle of sheet iron separated me from this ocean with which I was still unfamiliar.

Crossing through the lounge, I arrived at the door, contrived in one of the canted corners, that opened into the captain’s stateroom. Much to my astonishment, this door was ajar. I instinctively recoiled. If Captain Nemo was in his stateroom, he might see me. But, not hearing any sounds, I approached. The stateroom was deserted. I pushed the door open. I took a few steps inside. Still the same austere, monastic appearance.

Just then my eye was caught by some etchings hanging on the wall, which I hadn’t noticed during my first visit. They were portraits of great men of history who had spent their lives in perpetual devotion to a great human ideal: Thaddeus Kosciusko, the hero whose dying words had been Finis Poloniae;* Markos Botzaris, for modern Greece the reincarnation of Sparta’s King Leonidas; Daniel O’Connell, Ireland’s defender; George Washington, founder of the American Union; Daniele Manin, the Italian patriot; Abraham Lincoln, dead from the bullet of a believer in slavery; and finally, that martyr for the redemption of the black race, John Brown, hanging from his gallows as Victor Hugo’s pencil has so terrifyingly depicted.

*Latin: “Save Poland’s borders.” Ed.

What was the bond between these heroic souls and the soul of Captain Nemo? From this collection of portraits could I finally unravel the mystery of his existence? Was he a fighter for oppressed peoples, a liberator of enslaved races? Had he figured in the recent political or social upheavals of this century? Was he a hero of that dreadful civil war in America, a war lamentable yet forever glorious . . . ?

Suddenly the clock struck eight. The first stroke of its hammer on the chime snapped me out of my musings. I shuddered as if some invisible eye had plunged into my innermost thoughts, and I rushed outside the stateroom.

There my eyes fell on the compass. Our heading was still northerly. The log indicated a moderate speed, the pressure gauge a depth of about sixty feet. So circumstances were in favor of the Canadian’s plans.

I stayed in my stateroom. I dressed warmly: fishing boots, otter cap, coat of fan-mussel fabric lined with sealskin. I was ready. I was waiting. Only the propeller’s vibrations disturbed the deep silence reigning on board. I cocked an ear and listened. Would a sudden outburst of voices tell me that Ned Land’s escape plans had just been detected? A ghastly uneasiness stole through me. I tried in vain to recover my composure.

A few minutes before nine o’clock, I glued my ear to the captain’s door. Not a sound. I left my stateroom and returned to the lounge, which was deserted and plunged in near darkness.

I opened the door leading to the library. The same inadequate light, the same solitude. I went to man my post near the door opening into the well of the central companionway. I waited for Ned Land’s signal.

At this point the propeller’s vibrations slowed down appreciably, then they died out altogether. Why was the Nautilus stopping? Whether this layover would help or hinder Ned Land’s schemes I couldn’t have said.

The silence was further disturbed only by the pounding of my heart.

Suddenly I felt a mild jolt. I realized the Nautilus had come to rest on the ocean floor. My alarm increased. The Canadian’s signal hadn’t reached me. I longed to rejoin Ned Land and urge him to postpone his attempt. I sensed that we were no longer navigating under normal conditions.

Just then the door to the main lounge opened and Captain Nemo appeared. He saw me, and without further preamble:

“Ah, professor,” he said in an affable tone, “I’ve been looking for you. Do you know your Spanish history?”

Even if he knew it by heart, a man in my disturbed, befuddled condition couldn’t have quoted a syllable of his own country’s history.

“Well?” Captain Nemo went on. “Did you hear my question? Do you know the history of Spain?”

“Very little of it,” I replied.

“The most learned men,” the captain said, “still have much to learn. Have a seat,” he added, “and I’ll tell you about an unusual episode in this body of history.”

The captain stretched out on a couch, and I mechanically took a seat near him, but half in the shadows.

“Professor,” he said, “listen carefully. This piece of history concerns you in one definite respect, because it will answer a question you’ve no doubt been unable to resolve.”

“I’m listening, captain,” I said, not knowing what my partner in this dialogue was driving at, and wondering if this incident related to our escape plans.

“Professor,” Captain Nemo went on, “if you’re amenable, we’ll go back in time to 1702. You’re aware of the fact that in those days your King Louis XIV thought an imperial gesture would suffice to humble the Pyrenees in the dust, so he inflicted his grandson, the Duke of Anjou, on the Spaniards. Reigning more or less poorly under the name King Philip V, this aristocrat had to deal with mighty opponents abroad.

“In essence, the year before, the royal houses of Holland, Austria, and England had signed a treaty of alliance at The Hague, aiming to wrest the Spanish crown from King Philip V and to place it on the head of an archduke whom they prematurely dubbed King Charles III.

“Spain had to withstand these allies. But the country had practically no army or navy. Yet it wasn’t short of money, provided that its galleons, laden with gold and silver from America, could enter its ports. Now then, late in 1702 Spain was expecting a rich convoy, which France ventured to escort with a fleet of twenty-three vessels under the command of Admiral de Chateau-Renault, because by that time the allied navies were roving the Atlantic.

“This convoy was supposed to put into Cadiz, but after learning that the English fleet lay across those waterways, the admiral decided to make for a French port.

“The Spanish commanders in the convoy objected to this decision. They wanted to be taken to a Spanish port, if not to Cadiz, then to the Bay of Vigo, located on Spain’s northwest coast and not blockaded.

“Admiral de Chateau-Renault was so indecisive as to obey this directive, and the galleons entered the Bay of Vigo.

“Unfortunately this bay forms an open, offshore mooring that’s impossible to defend. So it was essential to hurry and empty the galleons before the allied fleets arrived, and there would have been ample time for this unloading, if a wretched question of trade agreements hadn’t suddenly come up.

“Are you clear on the chain of events?” Captain Nemo asked me.

“Perfectly clear,” I said, not yet knowing why I was being given this history lesson.

“Then I’ll continue. Here’s what came to pass. The tradesmen of Cadiz had negotiated a charter whereby they were to receive all merchandise coming from the West Indies. Now then, unloading the ingots from those galleons at the port of Vigo would have been a violation of their rights. So they lodged a complaint in Madrid, and they obtained an order from the indecisive King Philip V: without unloading, the convoy would stay in custody at the offshore mooring of Vigo until the enemy fleets had retreated.

“Now then, just as this decision was being handed down, English vessels arrived in the Bay of Vigo on October 22, 1702. Despite his inferior forces, Admiral de Chateau-Renault fought courageously. But when he saw that the convoy’s wealth was about to fall into enemy hands, he burned and scuttled the galleons, which went to the bottom with their immense treasures.”

Captain Nemo stopped. I admit it: I still couldn’t see how this piece of history concerned me.

“Well?” I asked him.

“Well, Professor Aronnax,” Captain Nemo answered me, “we’re actually in that Bay of Vigo, and all that’s left is for you to probe the mysteries of the place.”

The captain stood up and invited me to follow him. I’d had time to collect myself. I did so. The lounge was dark, but the sea’s waves sparkled through the transparent windows. I stared.

Around the Nautilus for a half-mile radius, the waters seemed saturated with electric light. The sandy bottom was clear and bright. Dressed in diving suits, crewmen were busy clearing away half-rotted barrels and disemboweled trunks in the midst of the dingy hulks of ships. Out of these trunks and kegs spilled ingots of gold and silver, cascades of jewels, pieces of eight. The sand was heaped with them. Then, laden with these valuable spoils, the men returned to the Nautilus, dropped off their burdens inside, and went to resume this inexhaustible fishing for silver and gold.

I understood. This was the setting of that battle on October 22, 1702. Here, in this very place, those galleons carrying treasure to the Spanish government had gone to the bottom. Here, whenever he needed, Captain Nemo came to withdraw these millions to ballast his Nautilus. It was for him, for him alone, that America had yielded up its precious metals. He was the direct, sole heir to these treasures wrested from the Incas and those peoples conquered by Hernando Cortez!

“Did you know, professor,” he asked me with a smile, “that the sea contained such wealth?”

“I know it’s estimated,” I replied, “that there are 2,000,000 metric tons of silver held in suspension in seawater.”

“Surely, but in extracting that silver, your expenses would outweigh your profits. Here, by contrast, I have only to pick up what other men have lost, and not only in this Bay of Vigo but at a thousand other sites where ships have gone down, whose positions are marked on my underwater chart. Do you understand now that I’m rich to the tune of billions?”

“I understand, captain. Nevertheless, allow me to inform you that by harvesting this very Bay of Vigo, you’re simply forestalling the efforts of a rival organization.”

“What organization?”

“A company chartered by the Spanish government to search for these sunken galleons. The company’s investors were lured by the bait of enormous gains, because this scuttled treasure is estimated to be worth 500,000,000 francs.”

“It was 500,000,000 francs,” Captain Nemo replied, “but no more!”

“Right,” I said. “Hence a timely warning to those investors would be an act of charity. Yet who knows if it would be well received? Usually what gamblers regret the most isn’t the loss of their money so much as the loss of their insane hopes. But ultimately I feel less sorry for them than for the thousands of unfortunate people who would have benefited from a fair distribution of this wealth, whereas now it will be of no help to them!”

No sooner had I voiced this regret than I felt it must have wounded Captain Nemo.

“No help!” he replied with growing animation. “Sir, what makes you assume this wealth goes to waste when I’m the one amassing it? Do you think I toil to gather this treasure out of selfishness? Who says I don’t put it to good use? Do you think I’m unaware of the suffering beings and oppressed races living on this earth, poor people to comfort, victims to avenge? Don’t you understand . . . ?”

Captain Nemo stopped on these last words, perhaps sorry that he had said too much. But I had guessed. Whatever motives had driven him to seek independence under the seas, he remained a human being before all else! His heart still throbbed for suffering humanity, and his immense philanthropy went out both to downtrodden races and to individuals!

And now I knew where Captain Nemo had delivered those millions, when the Nautilus navigated the waters where Crete was in rebellion against the Ottoman Empire!

CHAPTER 9

A Lost Continent

THE NEXT MORNING, February 19, I beheld the Canadian entering my stateroom. I was expecting this visit. He wore an expression of great disappointment.

“Well, sir?” he said to me.

“Well, Ned, the fates were against us yesterday.”

“Yes! That damned captain had to call a halt just as we were going to escape from his boat.”

“Yes, Ned, he had business with his bankers.”

“His bankers?”

“Or rather his bank vaults. By which I mean this ocean, where his wealth is safer than in any national treasury.”

I then related the evening’s incidents to the Canadian, secretly hoping he would come around to the idea of not deserting the captain; but my narrative had no result other than Ned’s voicing deep regret that he hadn’t strolled across the Vigo battlefield on his own behalf.

“Anyhow,” he said, “it’s not over yet! My first harpoon missed, that’s all! We’ll succeed the next time, and as soon as this evening, if need be . . .”

“What’s the Nautilus’s heading?” I asked.

“I’ve no idea,” Ned replied.

“All right, at noon we’ll find out what our position is!”

The Canadian returned to Conseil’s side. As soon as I was dressed, I went into the lounge. The compass wasn’t encouraging. The Nautilus’s course was south-southwest. We were turning our backs on Europe.

I could hardly wait until our position was reported on the chart. Near 11:30 the ballast tanks emptied, and the submersible rose to the surface of the ocean. I leaped onto the platform. Ned Land was already there.

No more shore in sight. Nothing but the immenseness of the sea. A few sails were on the horizon, no doubt ships going as far as Cape São Roque to find favorable winds for doubling the Cape of Good Hope. The sky was overcast. A squall was on the way.

Furious, Ned tried to see through the mists on the horizon. He still hoped that behind all that fog there lay those shores he longed for.

At noon the sun made a momentary appearance. Taking advantage of this rift in the clouds, the chief officer took the orb’s altitude. Then the sea grew turbulent, we went below again, and the hatch closed once more.

When I consulted the chart an hour later, I saw that the Nautilus’s position was marked at longitude 16 degrees 17’ and latitude 33 degrees 22’, a good 150 leagues from the nearest coast. It wouldn’t do to even dream of escaping, and I’ll let the reader decide how promptly the Canadian threw a tantrum when I ventured to tell him our situation.

As for me, I wasn’t exactly grief-stricken. I felt as if a heavy weight had been lifted from me, and I was able to resume my regular tasks in a state of comparative calm.

Near eleven o’clock in the evening, I received a most unexpected visit from Captain Nemo. He asked me very graciously if I felt exhausted from our vigil the night before. I said no.

“Then, Professor Aronnax, I propose an unusual excursion.”

“Propose away, captain.”

“So far you’ve visited the ocean depths only by day and under sunlight. Would you like to see these depths on a dark night?”

“Very much.”

“I warn you, this will be an exhausting stroll. We’ll need to walk long hours and scale a mountain. The roads aren’t terribly well kept up.”

“Everything you say, captain, just increases my curiosity. I’m ready to go with you.”

“Then come along, professor, and we’ll go put on our diving suits.”

Arriving at the wardrobe, I saw that neither my companions nor any crewmen would be coming with us on this excursion. Captain Nemo hadn’t even suggested my fetching Ned or Conseil.

In a few moments we had put on our equipment. Air tanks, abundantly charged, were placed on our backs, but the electric lamps were not in readiness. I commented on this to the captain.

“They’ll be useless to us,” he replied.

I thought I hadn’t heard him right, but I couldn’t repeat my comment because the captain’s head had already disappeared into its metal covering. I finished harnessing myself, I felt an alpenstock being placed in my hand, and a few minutes later, after the usual procedures, we set foot on the floor of the Atlantic, 300 meters down.

Midnight was approaching. The waters were profoundly dark, but Captain Nemo pointed to a reddish spot in the distance, a sort of wide glow shimmering about two miles from the Nautilus. What this fire was, what substances fed it, how and why it kept burning in the liquid mass, I couldn’t say. Anyhow it lit our way, although hazily, but I soon grew accustomed to this unique gloom, and in these circumstances I understood the uselessness of the Ruhmkorff device.

Side by side, Captain Nemo and I walked directly toward this conspicuous flame. The level seafloor rose imperceptibly. We took long strides, helped by our alpenstocks; but in general our progress was slow, because our feet kept sinking into a kind of slimy mud mixed with seaweed and assorted flat stones.

As we moved forward, I heard a kind of pitter-patter above my head. Sometimes this noise increased and became a continuous crackle. I soon realized the cause. It was a heavy rainfall rattling on the surface of the waves. Instinctively I worried that I might get soaked! By water in the midst of water! I couldn’t help smiling at this outlandish notion. But to tell the truth, wearing these heavy diving suits, you no longer feel the liquid element, you simply think you’re in the midst of air a little denser than air on land, that’s all.

After half an hour of walking, the seafloor grew rocky. Jellyfish, microscopic crustaceans, and sea-pen coral lit it faintly with their phosphorescent glimmers. I glimpsed piles of stones covered by a couple million zoophytes and tangles of algae. My feet often slipped on this viscous seaweed carpet, and without my alpenstock I would have fallen more than once. When I turned around, I could still see the Nautilus’s whitish beacon, which was starting to grow pale in the distance.

Those piles of stones just mentioned were laid out on the ocean floor with a distinct but inexplicable symmetry. I spotted gigantic furrows trailing off into the distant darkness, their length incalculable. There also were other peculiarities I couldn’t make sense of. It seemed to me that my heavy lead soles were crushing a litter of bones that made a dry crackling noise. So what were these vast plains we were now crossing? I wanted to ask the captain, but I still didn’t grasp that sign language that allowed him to chat with his companions when they went with him on his underwater excursions.

Meanwhile the reddish light guiding us had expanded and inflamed the horizon. The presence of this furnace under the waters had me extremely puzzled. Was it some sort of electrical discharge? Was I approaching some natural phenomenon still unknown to scientists on shore? Or, rather (and this thought did cross my mind), had the hand of man intervened in that blaze? Had human beings fanned those flames? In these deep strata would I meet up with more of Captain Nemo’s companions, friends he was about to visit who led lives as strange as his own? Would I find a whole colony of exiles down here, men tired of the world’s woes, men who had sought and found independence in the ocean’s lower depths? All these insane, inadmissible ideas dogged me, and in this frame of mind, continually excited by the series of wonders passing before my eyes, I wouldn’t have been surprised to find on this sea bottom one of those underwater towns Captain Nemo dreamed about!

Our path was getting brighter and brighter. The red glow had turned white and was radiating from a mountain peak about 800 feet high. But what I saw was simply a reflection produced by the crystal waters of these strata. The furnace that was the source of this inexplicable light occupied the far side of the mountain.

In the midst of the stone mazes furrowing this Atlantic seafloor, Captain Nemo moved forward without hesitation. He knew this dark path. No doubt he had often traveled it and was incapable of losing his way. I followed him with unshakeable confidence. He seemed like some Spirit of the Sea, and as he walked ahead of me, I marveled at his tall figure, which stood out in black against the glowing background of the horizon.

It was one o’clock in the morning. We arrived at the mountain’s lower gradients. But in grappling with them, we had to venture up difficult trails through a huge thicket.

Yes, a thicket of dead trees! Trees without leaves, without sap, turned to stone by the action of the waters, and crowned here and there by gigantic pines. It was like a still-erect coalfield, its roots clutching broken soil, its boughs clearly outlined against the ceiling of the waters like thin, black, paper cutouts. Picture a forest clinging to the sides of a peak in the Harz Mountains, but a submerged forest. The trails were cluttered with algae and fucus plants, hosts of crustaceans swarming among them. I plunged on, scaling rocks, straddling fallen tree trunks, snapping marine creepers that swayed from one tree to another, startling the fish that flitted from branch to branch. Carried away, I didn’t feel exhausted any more. I followed a guide who was immune to exhaustion.

What a sight! How can I describe it! How can I portray these woods and rocks in this liquid setting, their lower parts dark and sullen, their upper parts tinted red in this light whose intensity was doubled by the reflecting power of the waters! We scaled rocks that crumbled behind us, collapsing in enormous sections with the hollow rumble of an avalanche. To our right and left there were carved gloomy galleries where the eye lost its way. Huge glades opened up, seemingly cleared by the hand of man, and I sometimes wondered whether some residents of these underwater regions would suddenly appear before me.

But Captain Nemo kept climbing. I didn’t want to fall behind. I followed him boldly. My alpenstock was a great help. One wrong step would have been disastrous on the narrow paths cut into the sides of these chasms, but I walked along with a firm tread and without the slightest feeling of dizziness. Sometimes I leaped over a crevasse whose depth would have made me recoil had I been in the midst of glaciers on shore; sometimes I ventured out on a wobbling tree trunk fallen across a gorge, without looking down, having eyes only for marveling at the wild scenery of this region. There, leaning on erratically cut foundations, monumental rocks seemed to defy the laws of balance. From between their stony knees, trees sprang up like jets under fearsome pressure, supporting other trees that supported them in turn. Next, natural towers with wide, steeply carved battlements leaned at angles that, on dry land, the laws of gravity would never have authorized.

And I too could feel the difference created by the water’s powerful density—despite my heavy clothing, copper headpiece, and metal soles, I climbed the most impossibly steep gradients with all the nimbleness, I swear it, of a chamois or a Pyrenees mountain goat!

As for my account of this excursion under the waters, I’m well aware that it sounds incredible! I’m the chronicler of deeds seemingly impossible and yet incontestably real. This was no fantasy. This was what I saw and felt!

Two hours after leaving the Nautilus, we had cleared the timberline, and 100 feet above our heads stood the mountain peak, forming a dark silhouette against the brilliant glare that came from its far slope. Petrified shrubs rambled here and there in sprawling zigzags. Fish rose in a body at our feet like birds startled in tall grass. The rocky mass was gouged with impenetrable crevices, deep caves, unfathomable holes at whose far ends I could hear fearsome things moving around. My blood would curdle as I watched some enormous antenna bar my path, or saw some frightful pincer snap shut in the shadow of some cavity! A thousand specks of light glittered in the midst of the gloom. They were the eyes of gigantic crustaceans crouching in their lairs, giant lobsters rearing up like spear carriers and moving their claws with a scrap-iron clanking, titanic crabs aiming their bodies like cannons on their carriages, and hideous devilfish intertwining their tentacles like bushes of writhing snakes.

What was this astounding world that I didn’t yet know? In what order did these articulates belong, these creatures for which the rocks provided a second carapace? Where had nature learned the secret of their vegetating existence, and for how many centuries had they lived in the ocean’s lower strata?

But I couldn’t linger. Captain Nemo, on familiar terms with these dreadful animals, no longer minded them. We arrived at a preliminary plateau where still other surprises were waiting for me. There picturesque ruins took shape, betraying the hand of man, not our Creator. They were huge stacks of stones in which you could distinguish the indistinct forms of palaces and temples, now arrayed in hosts of blossoming zoophytes, and over it all, not ivy but a heavy mantle of algae and fucus plants.