Figure 22.—1756: The highly elaborated stock and

rosette-incised wedge of the smoothing plane recall the decoration on

furniture of the period. The plane is of Dutch origin. (Smithsonian

photo 49792-F.)

Figure 22.—1756: The highly elaborated stock and

rosette-incised wedge of the smoothing plane recall the decoration on

furniture of the period. The plane is of Dutch origin. (Smithsonian

photo 49792-F.)

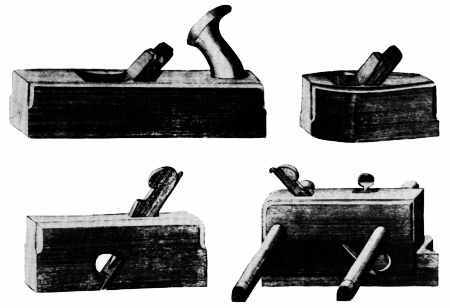

Figure 23.—1809: This bench plane of German origin is

dated 1809. It is of a traditional form that persists to the present

day. The planes pictured in figures 21, 22, and 23 are similar to the

type brought to North America by non-English colonists. (Private

collection. Smithsonian photo 49793-F.)

Figure 23.—1809: This bench plane of German origin is

dated 1809. It is of a traditional form that persists to the present

day. The planes pictured in figures 21, 22, and 23 are similar to the

type brought to North America by non-English colonists. (Private

collection. Smithsonian photo 49793-F.)

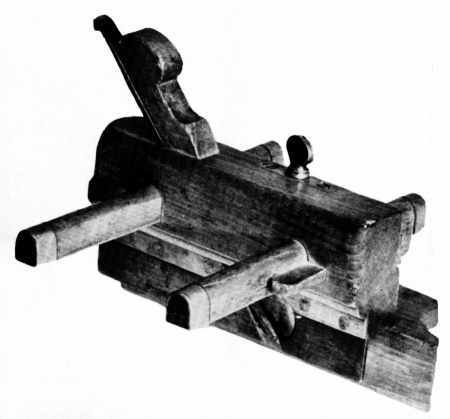

Figure 24.—About 1818: This plow plane, used to cut

narrow channels on the edges of boards, was made by G. White of

Philadelphia in the early 19th century. It is essentially the same tool

depicted in the catalogues of Sheffield manufactures and in the plates

from Martin and Nicholson. The pattern of the basic bench tools used in

America consistently followed British design, at least until the last

quarter of the 19th century. (Private collection. Smithsonian photo

49794-E.)

Figure 24.—About 1818: This plow plane, used to cut

narrow channels on the edges of boards, was made by G. White of

Philadelphia in the early 19th century. It is essentially the same tool

depicted in the catalogues of Sheffield manufactures and in the plates

from Martin and Nicholson. The pattern of the basic bench tools used in

America consistently followed British design, at least until the last

quarter of the 19th century. (Private collection. Smithsonian photo

49794-E.)

Figure 25. 1830–1840: The design of the rabbet plane,

used to cut a groove of fixed width and depth on the edge of a board,

was not improved upon in the 19th century. The carpenter's dependence on

this tool lessened only after the perfection of multipurpose metallic

planes that could be readily converted to cut a "rabbet." (Private

collection. Smithsonian photo 494789-H).

Figure 25. 1830–1840: The design of the rabbet plane,

used to cut a groove of fixed width and depth on the edge of a board,

was not improved upon in the 19th century. The carpenter's dependence on

this tool lessened only after the perfection of multipurpose metallic

planes that could be readily converted to cut a "rabbet." (Private

collection. Smithsonian photo 494789-H).

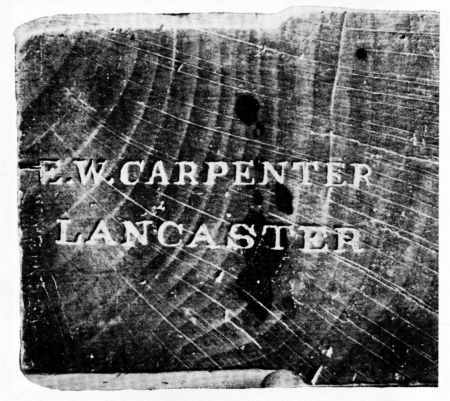

The question of dating arises, since only the Klock piece is firmly fixed. How, for example, is the early 19th-century attribution arrived at for the planes inscribed White and Carpenter? First, the nature of the stamped name "G. White" is of proper character for the period. Second, G. White is listed in the Philadelphia city directories as a "plane-maker" between the years 1818 and 1820, working at the back of 5 Filbert Street and later at 34 Juliana Street. Third, internal evidence on the plane itself gives a clue. In this case, the hardware—rivets and furrels—is similar if not identical to that found on firearms of the period, weapons whose dates of manufacture are known. The decorative molding on the fence of this plane is proper for the period; this is not a reliable guide, however, since similar moldings are retained throughout the century. Finally, the plane is equipped with a fence controlled by slide-arms, fixed with wedges and not by adjustable screw arms. After 1830, tools of high quality, such as White's, invariably have the screw arms. The rabbet plane, made by Carpenter, is traceable via another route, the U.S. Patent Office records. Carpenter, self-designated "toolmaker of Lancaster," submitted patents for the improvement of wood planes between 1831 and 1849. Examples of Carpenter's work, always stamped as shown in figure 27, survive, both dated and undated. There are several of his planes in the collections of the Bucks County Historical Society, and dated pieces are known in private collections.

Inherent in the bench planes is a feeling of motion, particularly in the plow and the rabbet where basic design alone conveys the idea that they were meant to move over fixed surfaces. Of the three examples, only the brass tippings and setscrew of the plow plane suggest any enrichment, and of course these were not intended for decoration; in later years, however, boxwood, fruitwood, and even ivory tips were added to the more expensive factory models. Also unintentional, but pleasing, is the distinctive throat of the rabbet plane—a design that developed to permit easy discharge of shavings, and one that mass manufacture did not destroy.

Figure 26.—1818: The jack plane, used first by the

carpenter for rapid surfacing, is distinguished primarily by the bezeled

and slightly convex edge of its cutting iron. As with the plow and the

rabbet, its shape is ubiquitous. Dated and marked A. Klock, this

American example follows precisely those detailed in Sheffield pattern

books. (Smithsonian photo 49794-C.)

Figure 26.—1818: The jack plane, used first by the

carpenter for rapid surfacing, is distinguished primarily by the bezeled

and slightly convex edge of its cutting iron. As with the plow and the

rabbet, its shape is ubiquitous. Dated and marked A. Klock, this

American example follows precisely those detailed in Sheffield pattern

books. (Smithsonian photo 49794-C.)

Figure 27.—1830–1840: Detail of the rabbet plane (fig.

25) showing the characteristic stamp of E.W. Carpenter. (Smithsonian

photo 49794-D.)

Figure 27.—1830–1840: Detail of the rabbet plane (fig.

25) showing the characteristic stamp of E.W. Carpenter. (Smithsonian

photo 49794-D.)

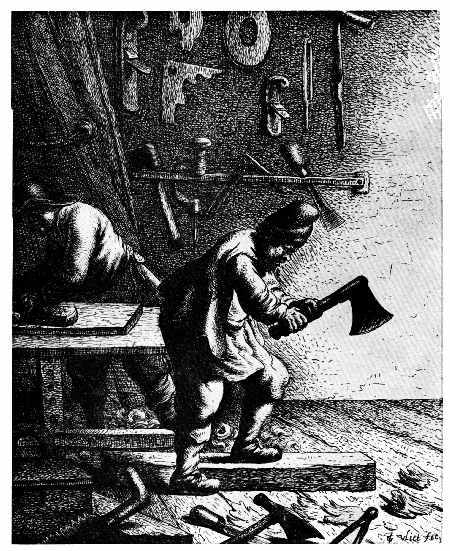

Figure 28.—About 1631: The preceding illustrations

emphasize the divergent appearance of European and Anglo-American tools.

This, however, was not always the case. The woodworker's shop by the

Dutch engraver Jan Van Vliet suggests the similarity between English and

European tool types in the 17th century. Note in particular the planes,

axe, brace, and auger as compared to Moxon. (Library of Congress,

Division of Prints and Photographs.)

Figure 28.—About 1631: The preceding illustrations

emphasize the divergent appearance of European and Anglo-American tools.

This, however, was not always the case. The woodworker's shop by the

Dutch engraver Jan Van Vliet suggests the similarity between English and

European tool types in the 17th century. Note in particular the planes,

axe, brace, and auger as compared to Moxon. (Library of Congress,

Division of Prints and Photographs.)

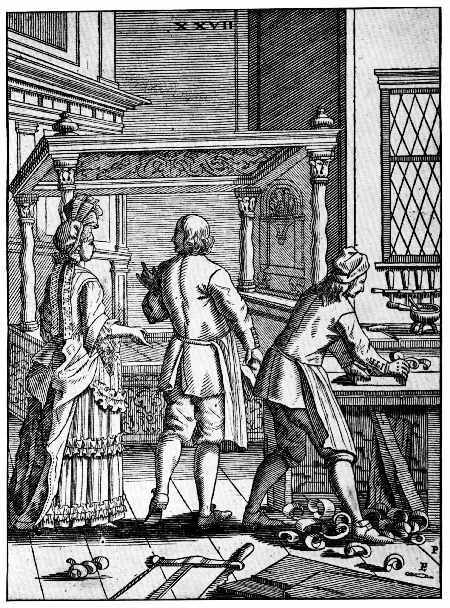

Figure 29.—1690: The cabinetmaker's shop from Elias

Pozelius, Orbus Pictus nach Zeichnugen der Susanna Maria Sandrart,

Nürnberg, 1690. (Library of Congress.)

Figure 29.—1690: The cabinetmaker's shop from Elias

Pozelius, Orbus Pictus nach Zeichnugen der Susanna Maria Sandrart,

Nürnberg, 1690. (Library of Congress.)

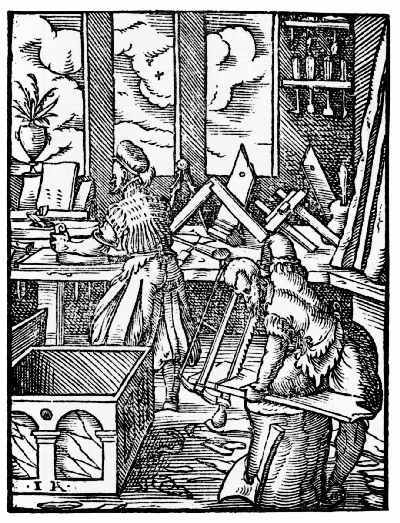

Figure 30.—1568: The woodworker's shop from Hans Sachs,

Eygentliche Beschrerbung Aller Stande ... mit Kunstreichen Figuren [by

Jost Amman], Frankfurt, 1568. (Library of Congress.)

Figure 30.—1568: The woodworker's shop from Hans Sachs,

Eygentliche Beschrerbung Aller Stande ... mit Kunstreichen Figuren [by

Jost Amman], Frankfurt, 1568. (Library of Congress.)

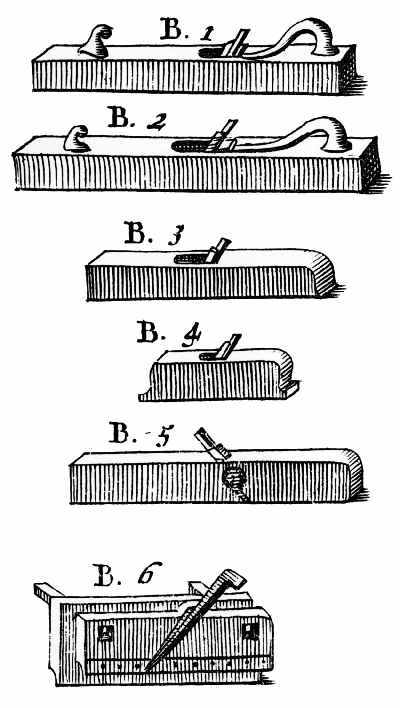

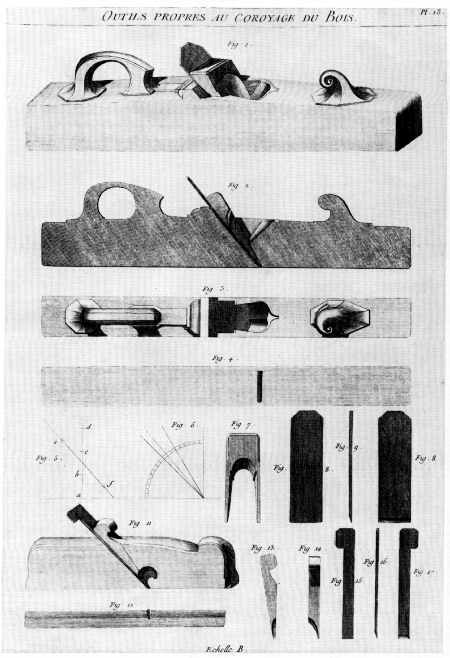

The divergence from European to an Anglo-American hand-tool design and the approximate date that it occurred can be suggested by a comparison of contemporary illustrations. The change in the wooden bench plane can be followed from the early 17th century through its standardization at the end of the 18th century. Examine first the planes as drawn in the 1630's by the Dutchman Jan Van Vliet (fig. 28), an etcher of Rembrandt's school at Leiden, and also the examples illustrated by Porzelius (fig. 29) and by Jost Amman (fig. 30). Compare them to Moxon's plate (fig. 31) from the Mechanick Exercises (3rd ed., 1703) and to the splendid drawing of the bench plane from André-Jacob Roubo's L'Art du menuisier, published in 1769 (fig. 32). In all of them, the rounded handle, or tote, and the fore-horn appear, characteristics of both European and English planes of the period before 1750. The similarity ends with the mass production of hand tools from the shops of the English toolmaking centers, principally Sheffield. An illustration from a pattern and design book of the Castle Hill Works, Sheffield, dating from the last quarter of the 18th century (fig. 33), shows the achieved, familiar form of the bench planes, as well as other tools. The use of this form in America is readily documented in Lewis Miller's self-portrait while working at his trade in York, Pennsylvania, in 1810 (fig. 34) and by the shop sign carved by Isaac Fowle in 1820 for John Bradford (fig. 35). In each example, the bench plane clearly follows the English prototype.

Figure 31.—1703: Detail of the bench planes from Moxon's

Mechanick Exercises.

Figure 31.—1703: Detail of the bench planes from Moxon's

Mechanick Exercises.

Figure 32.—1769: André-Jacob Roubo's precise rendering

of the bench plane retains the essential features shown by Moxon—the

rounded tote or handle and the curved fore-horn. (André-Jacob Roubo,

L'Art du menuisier, 1769.)

Figure 32.—1769: André-Jacob Roubo's precise rendering

of the bench plane retains the essential features shown by Moxon—the

rounded tote or handle and the curved fore-horn. (André-Jacob Roubo,

L'Art du menuisier, 1769.)

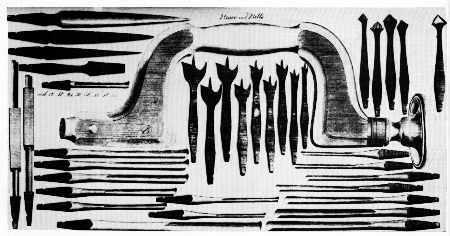

Figure 33.—Early 19th century: The bench plane

illustrated in Roubo or Moxon is seldom seen in American tool

collections. The bench planes, smoothing planes, rabbets, and plows

universally resemble those shown in this illustration from the pattern

book of the Castle Hill Works, Sheffield. (Book 87, Cutler and Company,

Castle Hill Works, Sheffield. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert

Museum.)

Figure 33.—Early 19th century: The bench plane

illustrated in Roubo or Moxon is seldom seen in American tool

collections. The bench planes, smoothing planes, rabbets, and plows

universally resemble those shown in this illustration from the pattern

book of the Castle Hill Works, Sheffield. (Book 87, Cutler and Company,

Castle Hill Works, Sheffield. Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert

Museum.)

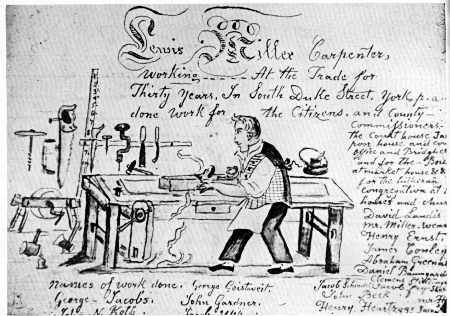

Figure 34.—About 1810: Lewis Miller working at his bench

in York, Pa. In a predominantly Pennsylvania-German settlement, the

plane used by Miller conforms to the Sheffield type illustrated in the

catalogue of the Castle Hill Works as shown in figure 33. (York County

Historical Society, York, Pa.)

Figure 34.—About 1810: Lewis Miller working at his bench

in York, Pa. In a predominantly Pennsylvania-German settlement, the

plane used by Miller conforms to the Sheffield type illustrated in the

catalogue of the Castle Hill Works as shown in figure 33. (York County

Historical Society, York, Pa.)

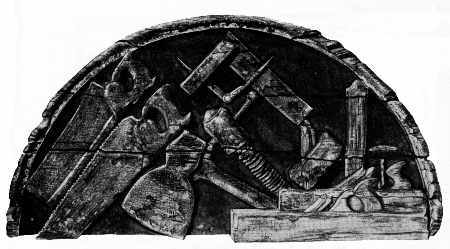

Figure 35.—1820: John Bradford's shop sign carved by

Isaac Fowle is a unique documentary of early 19th-century tool shapes

and is in the Bostonian Society, Boston, Mass. (Index of American

Design, The National Gallery, Washington, D.C.)

Figure 35.—1820: John Bradford's shop sign carved by

Isaac Fowle is a unique documentary of early 19th-century tool shapes

and is in the Bostonian Society, Boston, Mass. (Index of American

Design, The National Gallery, Washington, D.C.)

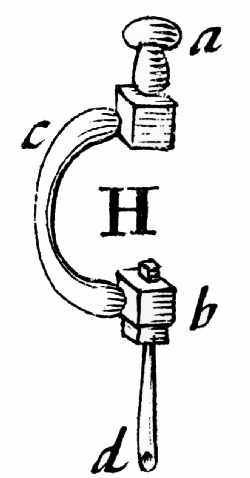

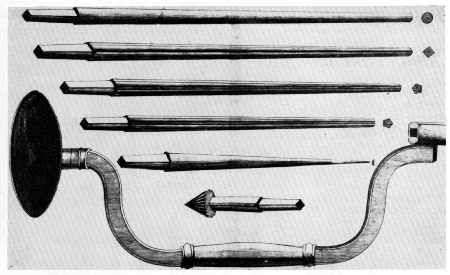

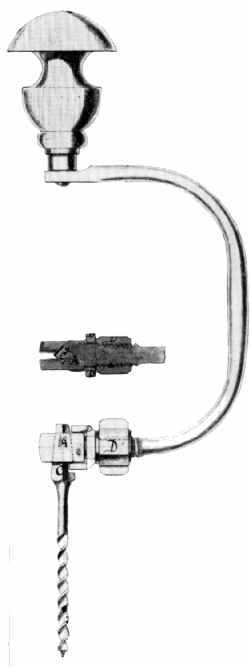

Figure 36.—1703: The joiner's brace and bit—a detail

from Moxon, Mechanick Exercises ..., London, 1703. (Library of

Congress, Smithsonian photo 56635.)

Figure 36.—1703: The joiner's brace and bit—a detail

from Moxon, Mechanick Exercises ..., London, 1703. (Library of

Congress, Smithsonian photo 56635.)

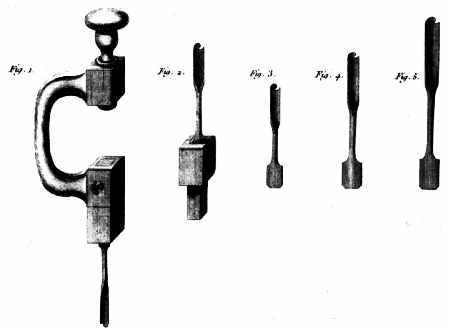

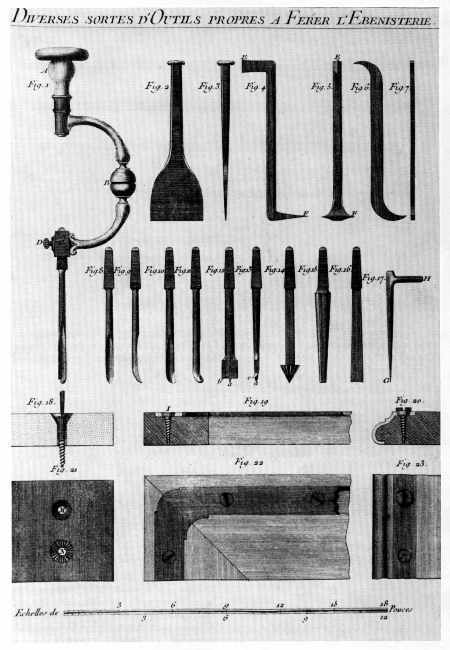

Figure 37.—1769: Roubo's illustration of the brace and

bit differs from Moxon's only in the precision of the delineation.

Contrast this form with that of the standard Sheffield version in figure

38 and the metallic braces illustrated in figures 40 through 44. From

these plates can be seen the progression of the bitstock toward its

ultimate perfection in the late 19th century. (André-Jacob Roubo, L'Art

du menuisier, 1769.)

Figure 37.—1769: Roubo's illustration of the brace and

bit differs from Moxon's only in the precision of the delineation.

Contrast this form with that of the standard Sheffield version in figure

38 and the metallic braces illustrated in figures 40 through 44. From

these plates can be seen the progression of the bitstock toward its

ultimate perfection in the late 19th century. (André-Jacob Roubo, L'Art

du menuisier, 1769.)

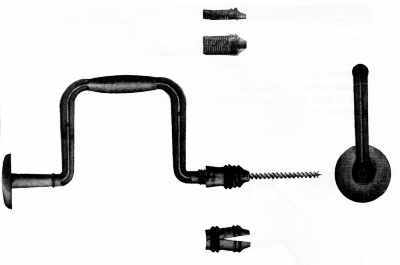

Figure 38.—Early 19th century: The mass-produced version

of the wooden brace and bit took the form illustrated in Book 87 of

Cutler's Castle Hill Works. (Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert

Museum.)

Figure 38.—Early 19th century: The mass-produced version

of the wooden brace and bit took the form illustrated in Book 87 of

Cutler's Castle Hill Works. (Courtesy of the Victoria and Albert

Museum.)

Figure 39.—18th century: The transitional form of the

wooden brace and bit incorporated the overall shape of the mass-produced

version but retained the archaic method of fastening the bit to the

chuck. The tool is of Dutch origin and suggests the influence of

Sheffield design on European tools. (Smithsonian photo 49792-E.)

Figure 39.—18th century: The transitional form of the

wooden brace and bit incorporated the overall shape of the mass-produced

version but retained the archaic method of fastening the bit to the

chuck. The tool is of Dutch origin and suggests the influence of

Sheffield design on European tools. (Smithsonian photo 49792-E.)

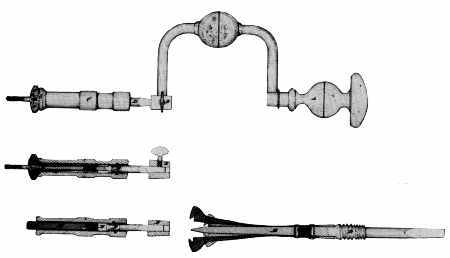

Figure 40.—1769: Roubo illustrated the metallic brace

and, in addition, suggested its use as a screwdriver. (André-Jacob

Roubo, L'Art du menuisier,1769.)

Figure 40.—1769: Roubo illustrated the metallic brace

and, in addition, suggested its use as a screwdriver. (André-Jacob

Roubo, L'Art du menuisier,1769.)

Figure 41.—About 1775: Ford, Whitmore and Brunton made

and sold clockmaker's braces of metal with a sweep and shank that was

imitated by American patentees in the 19th century. (Catalogue of Ford,

Whitmore and Brunton, Birmingham, England. Courtesy of the Birmingham

Reference Library.)

Figure 41.—About 1775: Ford, Whitmore and Brunton made

and sold clockmaker's braces of metal with a sweep and shank that was

imitated by American patentees in the 19th century. (Catalogue of Ford,

Whitmore and Brunton, Birmingham, England. Courtesy of the Birmingham

Reference Library.)

Figure 42.—1852: Nearly one hundred years after Roubo's

plate appeared, Jacob Switzer applied for a patent for an "Improved Self

Holding Screw Driver." The similarity of Switzer's drawing and Roubo's

plate is striking. (Original patent drawing 9,457, U.S. Patent Office,

Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 42.—1852: Nearly one hundred years after Roubo's

plate appeared, Jacob Switzer applied for a patent for an "Improved Self

Holding Screw Driver." The similarity of Switzer's drawing and Roubo's

plate is striking. (Original patent drawing 9,457, U.S. Patent Office,

Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 43.—1866: The simplicity and strength of the

brace proposed by J. Parker Gordon is in sharp contrast to the heavily

splinted sides of the wooden brace commonly used in mid-19th-century

America. (Original patent drawing 52,042, U.S. Patent Office, Record

Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 43.—1866: The simplicity and strength of the

brace proposed by J. Parker Gordon is in sharp contrast to the heavily

splinted sides of the wooden brace commonly used in mid-19th-century

America. (Original patent drawing 52,042, U.S. Patent Office, Record

Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 44.—1865: Milton nobles' patent perfecting the

chuck which held the auger bit was an important step along the path

which led ultimately to the complete acceptance of the metallic brace.

Barber's ratchet brace shown in figure 66 completes the metamorphosis of

this tool form in the United States. (Original patent drawing 51,660,

U.S. Patent Office, Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 44.—1865: Milton nobles' patent perfecting the

chuck which held the auger bit was an important step along the path

which led ultimately to the complete acceptance of the metallic brace.

Barber's ratchet brace shown in figure 66 completes the metamorphosis of

this tool form in the United States. (Original patent drawing 51,660,

U.S. Patent Office, Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

The carpenter's brace is another instance of divergent design after a common origin. Refer again to Van Vliet's etching of the woodworker's shop (fig. 28), to the detail from Moxon (fig. 36), and from Roubo (fig. 37). All show the brace in a form familiar since the Middle Ages, a shape common to both delineators and craftsmen of the Continent and the British Isles. But, as the plane changed, so changed the brace. The standard form of this tool as it was used and produced in the United States in the 19th century can be seen in another plate from the catalogue of the Castle Hill Works at Sheffield (fig. 38). This English influence on American tool design is no surprise, since as early as 1634 William Wood in New England's Prospect suggested that colonists take to the New World "All manner of Ironwares, as all manner of nailes for houses ... with Axes both broad and pitching ... All manners of Augers, piercing bits, Whip-saws, Two handed saws, Froes ..., rings for Bettle heads, and Iron-wedges."

Figure 45.—19th century: The upholsterer's hammer is an

unknown; it is not dated, its maker is anonymous, as is its user. It is

of American origin, yet of a style that might have been used in England

or on the Continent. This lack of provenance need not detract from its

significance as a material survival. This hammer, the brace (fig. 46),

the bevel (fig. 47), and the compass saw (fig. 48) are sufficiently

provocative in their design to conjure some image of a technology

dependent upon the skilled hand of craftsmen working in wood and of the

relationship between the hand, the tool, and the finished product.

(Smithsonian photo 49793-A.)

Figure 45.—19th century: The upholsterer's hammer is an

unknown; it is not dated, its maker is anonymous, as is its user. It is

of American origin, yet of a style that might have been used in England

or on the Continent. This lack of provenance need not detract from its

significance as a material survival. This hammer, the brace (fig. 46),

the bevel (fig. 47), and the compass saw (fig. 48) are sufficiently

provocative in their design to conjure some image of a technology

dependent upon the skilled hand of craftsmen working in wood and of the

relationship between the hand, the tool, and the finished product.

(Smithsonian photo 49793-A.)

Figure 46.—18th century: The brace and bit in its

nonfactory form conforms to a general design pattern in which none of

the components are ever precisely alike. This aspect of variety of

detail—sophistication, crudeness, decorative qualities or the

like—reflects something of the individuality of the toolmaker, a

quality completely lost in the standardization of the carpenter's brace.

(Smithsonian photo 49794-A.)

Figure 46.—18th century: The brace and bit in its

nonfactory form conforms to a general design pattern in which none of

the components are ever precisely alike. This aspect of variety of

detail—sophistication, crudeness, decorative qualities or the

like—reflects something of the individuality of the toolmaker, a

quality completely lost in the standardization of the carpenter's brace.

(Smithsonian photo 49794-A.)

English tool design in the 18th century also influenced the continental toolmakers. This can be seen in figure 39 in a transitional-type bitstock (accession 319556) from the Low Countries. Adopting an English shape, but still preserving the ancient lever device for holding the bit in place, the piece with its grapevine embellishment is a marked contrast to the severely functional brass chucks on braces of English manufacture. No less a contrast are metallic versions of the brace. These begin to appear with some regularity in the U.S. patent specifications of the 1840's; their design is apparently derived from 18th-century precedents. Roubo (fig. 40) illustrated a metal bitstock in 1769, as did Ford, Whitmore & Brunton, makers of jewelers' and watchmakers' tools, of Birmingham, England, in their trade catalogue of 1775 (fig. 41). Each suggests a prototype of the patented forms of the 1840's. For example, in 1852, Jacob Switzer of Basil, Ohio, suggested, as had Roubo a hundred years earlier, that the bitstock be used as a screwdriver (fig. 42); but far more interesting than Switzer's idea was his delineation of the brace itself, which he described as "an ordinary brace and bit stock" (U.S. pat. 9,457). The inference is that such a tool form was already a familiar one among the woodworking trades in the United States. Disregarding the screwdriver attachment, which is not without merit, Switzer's stock represents an accurate rendering of what was then a well-known form if not as yet a rival of the older wooden brace. Likewise, J. Parker Gordon's patent 52,042 of 1866 exemplifies the strengthening of a basic tool by the use of iron (fig. 43) and, as a result, the achievement of an even greater functionalism in design. The complete break with the medieval, however, is seen in a drawing submitted to the Commissioner of Patents in 1865 (pat. 51,660) by Milton V. Nobles of Rochester, New York.[9] Nobles' creation was of thoroughly modern design and appearance in which, unlike earlier types, the bit was held in place by a solid socket, split sleeve, and a tightening ring (fig. 44). In three centuries, three distinct design changes occurred in the carpenter's brace. First, about 1750, the so-called English or Sheffield bitstock appeared. This was followed in the very early 19th century by the reinforced English type whose sides were splinted by brass strips. Not only had the medieval form largely disappeared by the end of the 18th century, but so had the ancient lever-wedge method of fastening the bit in the stock, a device replaced by the pressure-spring button on the side of the chuck. Finally, in this evolution, came the metallic stock, not widely used in America until after the Civil War, that embodied in its design the influence of mass manufacture and in its several early versions all of the features of the modern brace and bit.

Figure 47.—18th century: The visually pleasing qualities

of walnut and brass provide a level of response to this joiner's bevel

quite apart from its technical significance. (Private collection.

Smithsonian photo 49793-B.)

Figure 47.—18th century: The visually pleasing qualities

of walnut and brass provide a level of response to this joiner's bevel

quite apart from its technical significance. (Private collection.

Smithsonian photo 49793-B.)

Figure 48.—18th century: The handle of the compass saw,

characteristically Dutch in shape, is an outstanding example of a

recurring functional design, one which varied according to the hand of

the sawer. (Smithsonian photo 49789-C.)

Figure 48.—18th century: The handle of the compass saw,

characteristically Dutch in shape, is an outstanding example of a

recurring functional design, one which varied according to the hand of

the sawer. (Smithsonian photo 49789-C.)

Henry Ward Beecher, impressed by the growing sophistication of the toolmakers, described the hand tool in a most realistic and objective manner as an "extension of a man's hand." The antiquarian, attuned to more subjective and romantic appraisals, will find this hardly sufficient. Look at the upholsterer's hammer (accession 61.35) seen in figure 45: there is no question that it is a response to a demanding task that required an efficient and not too forceful extension of the workman's hand. But there is another response to this implement: namely, the admiration for an unknown toolmaker who combined in an elementary striking tool a hammerhead of well-weighted proportion to be wielded gently through the medium of an extremely delicate handle. In short, here is an object about whose provenance one need know very little in order to enjoy it aesthetically. In a like manner, the 18th-century bitstock of Flemish origin (fig. 46), the English cabinetmaker's bevel of the same century (fig. 47), and the compass saw (accession 61.52, fig. 48) capture in their basic design something beyond the functional extension of the craftsman's hand. The slow curve of the bitstock, never identical from one early example to another, is lost in later factory-made versions; so too, with the coming of cheap steel, does the combination of wood (walnut) and brass used in the cabinetmaker's bevel slowly disappear; and, finally, in the custom-fitted pistol-like grip of the saw, there is an identity, in feeling at least, between craftsman and tool never quite achieved in later mass-produced versions.

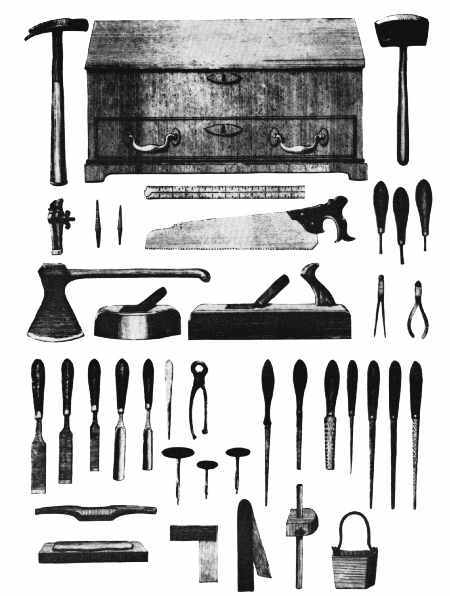

Figure 49.—Early 19th century: The designation

"gentleman's tool chest" required a chest of "high-style" but

necessitated no change in the tools it held. (Book 87, Cutler and

Company, Castle Hill Works, Sheffield. Courtesy of the Victoria and

Albert Museum.)

Figure 49.—Early 19th century: The designation

"gentleman's tool chest" required a chest of "high-style" but

necessitated no change in the tools it held. (Book 87, Cutler and

Company, Castle Hill Works, Sheffield. Courtesy of the Victoria and

Albert Museum.)

Figure 50.—19th century: The screwdriver, which began to

appear regularly on the woodworker's bench after 1800, did not share the

long evolution and tradition of other Anglo-American tool designs. The

screwdriver in its early versions frequently had a scalloped blade for

no other purpose than decoration. (Smithsonian photo 49794.)

Figure 50.—19th century: The screwdriver, which began to

appear regularly on the woodworker's bench after 1800, did not share the

long evolution and tradition of other Anglo-American tool designs. The

screwdriver in its early versions frequently had a scalloped blade for

no other purpose than decoration. (Smithsonian photo 49794.)

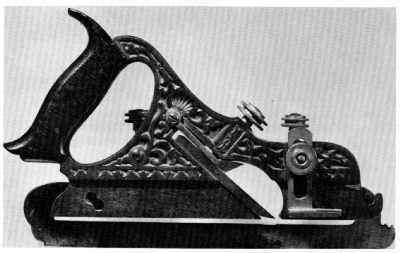

Figure 51.—1870: The use of a new material prompted a

departure from the traditional in shape and encouraged surface

elaboration. The tendency, however, was short lived and the

mass-produced metallic plane rapidly achieved a purity of design as

pleasing as its wooden predecessors. (Private collection. Smithsonian

photo 49789.)

Figure 51.—1870: The use of a new material prompted a

departure from the traditional in shape and encouraged surface

elaboration. The tendency, however, was short lived and the

mass-produced metallic plane rapidly achieved a purity of design as

pleasing as its wooden predecessors. (Private collection. Smithsonian

photo 49789.)

Occasionally, ruling taste is reflected in the design of the carpenter's equipment. Notable is the "gentleman's tool chest" (fig. 49) advertised in the pattern book of the Castle Hill Works. The bracket feet, brass pulls, and inlaid keyholes imitate the style of the domestic chest of drawers of the period 1790 to 1810—undoubtedly, features included by the manufacturer to appeal to a gentleman of refined taste. In contrast to this Sheffield product is the plate from Shaw's The Modern Architect. The concept of the builder-carpenter as a gentleman still prevails, although the idea in this American scene is conveyed in the mid-19th century through fashionable dress. The tools and in particular the tool chest reflect only the severest of functional lines (fig. 19, p. 196).

In deference to ruling taste, some tools lost for a time the clean lines that had long distinguished them. The screwdriver, simple in shape (accession 61.46) but in little demand until the 1840's, occasionally became most elaborate in its factory-made form (fig. 50) and departed noticeably from the unadorned style of traditional English and American tools. The scalloped blade, influenced by the rival styles rather than a technical need, seemed little related to the purpose of the tool.[10] No less archaic in decoration was the iron-bodied version of the plow plane (fig. 51). The Anglo-American tradition seems completely put aside. In its place is a most functional object, but one elaborately covered with a shell and vine motif! Patented in 1870 by Charles Miller and manufactured by the Stanley Rule and Level Company, this tool in its unadorned version is of a type that was much admired by the British experts at Philadelphia's Centennial Exhibition in 1876. What prompted such superfluous decoration on the plow plane? Perhaps it was to appeal to the flood of newly arrived American craftsmen who might find in the rococo something reminiscent of the older tools they had known in Europe. Perhaps it was simply the transference to the tool itself of the decorative work then demanded of the wood craftsmen. Or was it mainly a compulsion to dress, with little effort, a lackluster material that seemed stark and cold to Victorians accustomed to the ornateness being achieved elsewhere with the jigsaw and wood? Whatever the cause, the result did not persist long as a guide to hand-tool design. Instead, the strong, plain lines that had evolved over two centuries won universal endorsement at the Centennial Exhibition. The prize tools reflected little of the ornateness apparent in the wares of most of the other exhibitors. American makers of edge tools exhibiting at the Centennial showed the world not only examples of quality but of attractiveness as well.

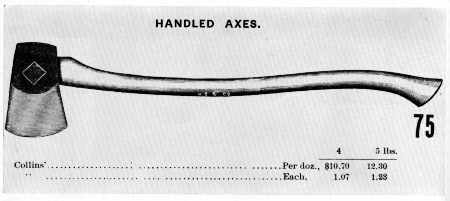

Figure 52.—19th century: The American axe was unexcelled

in design and ease of use. European observers praised it as distinctly

American. At the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 Collins and Company of

New York City was singled out as one of the outstanding manufacturers

exhibiting these axes, a reputation that persisted. (Tools for all

Trades, Hammacher, Schlemmer and Company, New York, 1896. Smithsonian

photo 56625.)

Figure 52.—19th century: The American axe was unexcelled

in design and ease of use. European observers praised it as distinctly

American. At the Centennial Exhibition in 1876 Collins and Company of

New York City was singled out as one of the outstanding manufacturers

exhibiting these axes, a reputation that persisted. (Tools for all

Trades, Hammacher, Schlemmer and Company, New York, 1896. Smithsonian

photo 56625.)

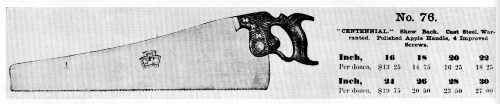

Figure 53.—1876: Disston and Sons long continued to

remind prospective buyers of the company's success at the Philadelphia

Centennial Exhibition by retaining the "Centennial Saw, No. 76" as a

brand name. (Illustrated Catalogue, Baldwin, Robbins and Company,

Boston, 1894. Smithsonian photo 56627.)

Figure 53.—1876: Disston and Sons long continued to

remind prospective buyers of the company's success at the Philadelphia

Centennial Exhibition by retaining the "Centennial Saw, No. 76" as a

brand name. (Illustrated Catalogue, Baldwin, Robbins and Company,

Boston, 1894. Smithsonian photo 56627.)

Change

American hand tools in 1876 did not achieve the popular acclaim accorded the Corliss engine, yet few products shown by American exhibitors were more highly praised by foreign experts. It seems justified to suggest that American edge tools displayed at the Centennial had reached their high point of development—a metamorphosis that began with the medieval European tool forms, moved through a period of reliance on English precedents, and ended, in the last quarter of the 19th century, with the production of American hand tools "occupying an enviable position before the world."[11]

Figure 54.—1809: The introduction of the gimlet-pointed

auger followed Ezra L'Hommedieu's patent of 1809. From this date until

its general disuse in the early 20th century, the conformation of the

tool remained unchanged, although the quality of steel and the precision

of the twist steadily improved. (Wash drawing from the restored patent

drawings awarded July 31, 1809, U.S. Patent Office, Record Group 241,

the National Archives. Smithsonian photo 49790-A.)

Figure 54.—1809: The introduction of the gimlet-pointed

auger followed Ezra L'Hommedieu's patent of 1809. From this date until

its general disuse in the early 20th century, the conformation of the

tool remained unchanged, although the quality of steel and the precision

of the twist steadily improved. (Wash drawing from the restored patent

drawings awarded July 31, 1809, U.S. Patent Office, Record Group 241,

the National Archives. Smithsonian photo 49790-A.)

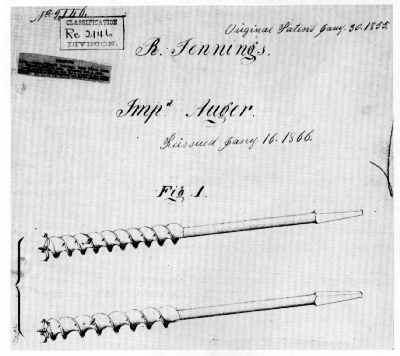

Figure 55.—1855: Russell Jennings' improved auger bits,

first patented in 1855, received superior citation at the Philadelphia

Centennial; in the years following, the trade name "Jennings" was seldom

omitted from trade catalogues. (Original wash drawing, patent drawing

submitted by R. Jennings, U.S. Patent Office, Record Group 241, the

National Archives.)

Figure 55.—1855: Russell Jennings' improved auger bits,

first patented in 1855, received superior citation at the Philadelphia

Centennial; in the years following, the trade name "Jennings" was seldom

omitted from trade catalogues. (Original wash drawing, patent drawing

submitted by R. Jennings, U.S. Patent Office, Record Group 241, the

National Archives.)

The tool most highly praised at Philadelphia was the American felling axe (fig. 52) "made out of a solid piece of cast steel" with the eye "punched out of the solid." When compared to other forms, the American axe was "more easily worked," and its shape permitted an easier withdrawal after striking.[12]

Sawmakers, too, were singled out for praise—in particular Disston & Sons (fig. 53) for "improvements in the form of the handles, and in the mode of fixing them to the saw." The Disston saw also embodied an improved blade shape which made it "lighter and more convenient by giving it a greater taper to the point." Sheffield saws, once supplied to most of the world, were not exhibited at Philadelphia, and the British expert lamented that our "monopoly remains with us no longer."[13]

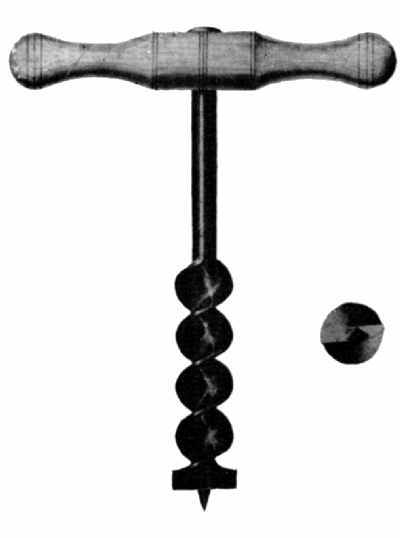

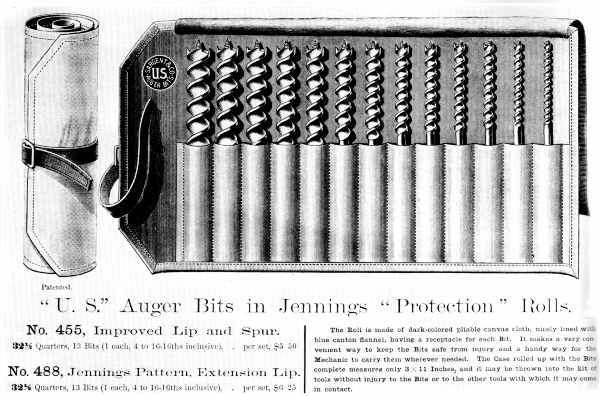

Figure 56.—1894: The Persistence of "jennings" As a

Trade Name is suggested by the vignette from the "Illustrated Catalogue"

of Baldwin, Robbins and Company, published in 1894. (Smithsonian photo

56628.)

Figure 56.—1894: The Persistence of "jennings" As a

Trade Name is suggested by the vignette from the "Illustrated Catalogue"

of Baldwin, Robbins and Company, published in 1894. (Smithsonian photo

56628.)

Augers, essential to "the heavier branches of the building trade ... [and] in the workshops of joiners, carpenters, cabinetmakers, turners, carvers, and by amateurs and others," were considered a "most important exhibit" at the Centennial. The auger had attained a perfection in "the accuracy of the twist, the various forms of the cutters, the quality of the steel, and fine finish of the twist and polish." The ancient pod or shell auger had nearly disappeared from use, to be replaced by "the screwed form of the tool" considerably refined by comparison to L'Hommedieu's prototype, patented in 1809 (fig. 54). Russell Jennings' patented auger bits (figs. 55–56) were cited for their "workmanship and quality," and, collectively, the Exhibition "fully established the reputation of American augers."[14] Likewise, makers of braces and bits were commended for the number of excellent examples shown. Some were a departure from the familiar design with "an expansive chuck for the bit," but others were simply elegant examples of the traditional brace, in wood, japanned and heavily reinforced with highly polished brass sidings. An example exhibited by E. Mills and Company, of Philadelphia, received a certification from the judges as being "of the best quality and finish" (fig. 57). The Mills brace, together with other award-winning tools of the company—drawknives, screwdrivers, and spokeshaves—is preserved in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution (accession 319326). Today as a group they confirm "the remarkably fine quality of ... both iron and steel" that characterized the manufacture of American edge tools in the second half of the 19th century.[15]

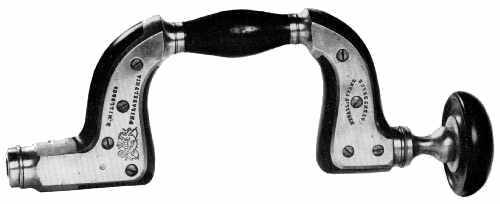

Figure 57.—1876: Japanned and splinted with heavy brass,

this brace was among the award-winning tools exhibited at the Centennial

by E. Mills and Company of Philadelphia. (Smithsonian photo 49792-D.)

Figure 57.—1876: Japanned and splinted with heavy brass,

this brace was among the award-winning tools exhibited at the Centennial

by E. Mills and Company of Philadelphia. (Smithsonian photo 49792-D.)

Figure 58.—1827: The bench planes exhibited at

Philadelphia in 1876 were a radical departure from the traditional. In

1827 H. Knowles patented an iron-bodied bench plane that portended a

change in form that would witness a substitution of steel for wood in

all critical areas of the tool's construction, and easy adjustment of

the cutting edge by a setscrew, and an increased flexibility that

allowed one plane to be used for several purposes. (Wash drawing from

the restored patent drawings, August 24, 1827, U.S. Patent Office,

Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 58.—1827: The bench planes exhibited at

Philadelphia in 1876 were a radical departure from the traditional. In

1827 H. Knowles patented an iron-bodied bench plane that portended a

change in form that would witness a substitution of steel for wood in

all critical areas of the tool's construction, and easy adjustment of

the cutting edge by a setscrew, and an increased flexibility that

allowed one plane to be used for several purposes. (Wash drawing from

the restored patent drawings, August 24, 1827, U.S. Patent Office,

Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

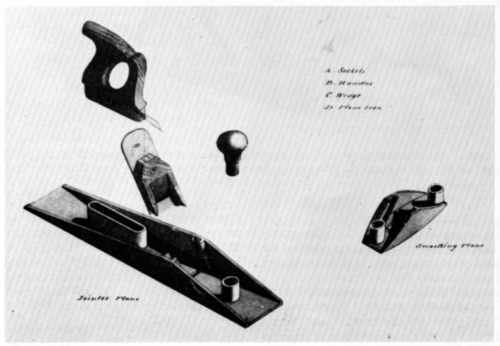

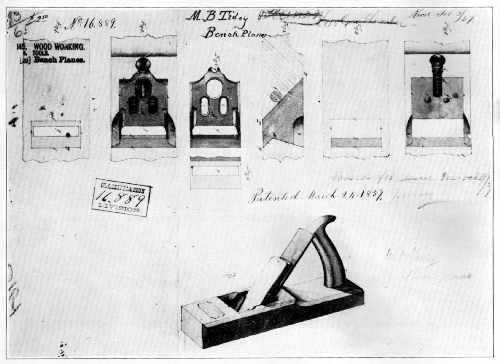

Figure 59.—1857: The addition of metallic parts to

critical areas of wear as suggested by M.B. Tidey did not at first

radically alter the design of the bench plane. (Wash drawing from U.S.

Patent Office, March 24, 1857, Record Group 241, the National

Archives.)

Figure 59.—1857: The addition of metallic parts to

critical areas of wear as suggested by M.B. Tidey did not at first

radically alter the design of the bench plane. (Wash drawing from U.S.

Patent Office, March 24, 1857, Record Group 241, the National

Archives.)

It is the plane, however, that best exemplifies the progress of tool design. In 1876, American planemakers were enthusiastically credited with having achieved "an important change in the structure of the tool."[16] Although change had been suggested by American patentees as early as the 1820's, mass production lagged until after the Civil War, and the use of this new tool form was not widespread outside of the United States. Hazard Knowles of Colchester, Connecticut, in 1827, patented a plane stock of cast iron which in many respects was a prototype of later Centennial models (fig. 58).[17] It is evident, even in its earliest manifestation, that the quest for improvement of the bench plane did not alter its sound design. In 1857, M.B. Tidey (fig. 59) listed several of the goals that motivated planemakers:

First to simplify the manufacturing of planes; second to render them more durable; third to retain a uniform mouth; fourth to obviate their clogging; and fifth the retention of the essential part of the plane when the stock is worn out.[18]

By far the greatest number of patents was concerned with perfecting an adjustable plane iron and methods of constructing the sole of a plane so that it would always be "true." Obviously the use of metal rather than the older medium, wood, was a natural step, but in the process of changing from the wood to the iron-bodied bench plane there were many transitional suggestions that combined both materials. Seth Howes of South Chatham, Massachusetts, in U.S. patent 37,694, specified:

This invention relates to an improvement in that class of planes which are commonly termed "bench-planes," comprising the foreplane, smoothing plane, jack plane, jointer, &c.

The invention consists in a novel and improved mode of adjusting the plane-iron to regulate the depth of the cut of the same, in connection with an adjustable cap, all being constructed and arranged in such a manner that the plane-iron may be "set" with the greatest facility and firmly retained in position by the adjustment simply of the cap to the plane-iron, after the latter is set, and the cap also rendered capable of being adjusted to compensate for the wear of the "sole" or face of the plane stock.

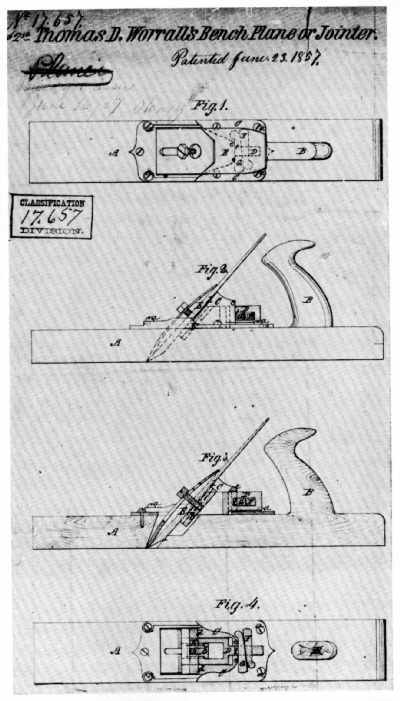

The stock of Howes' plane was wood combined with metal plates, caps, and screws. Thomas Worrall of Lowell was issued patent 17,657 for a plane based on the same general principle (fig. 60). Worrall claimed in his specifications of June 23, 1857:

the improved manufacture of [the] carpenter's bench plane or jointer as made with its handle, its wooden stock to which said handle is affixed, and a separate metallic cutter holder, and cutter clamping devices arranged together substantially as specified.

Finally patentees throughout the 19th century, faced with an increasing proliferation of tool types, frequently sought to perfect multipurpose implements of a type best represented later by the ubiquitous Stanley plane. The evolution of the all-purpose idea, which is incidentally not peculiar to hand tools alone, can be seen from random statements selected from U.S. patents for the improvement of bench planes. In 1864 Stephen Williams in the specifications of his patent 43,360 stated:

I denominate my improvement the "universal smoothing plane," because it belongs to that variety of planes in which the face is made changeable, so that it may be conveniently adapted to the planing of curved as well as straight surfaces. By the use of my improvement surfaces that are convex, concave, or straight may be easily worked, the face of the tool being readily changed from one form to another to suit the surface to which it is to be applied.

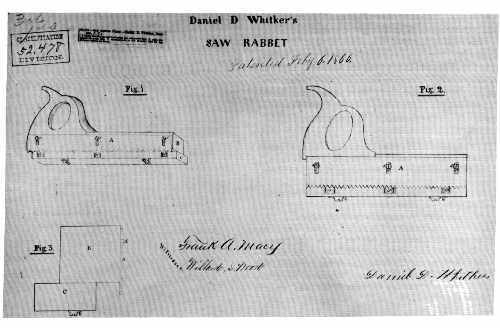

The announced object of Theodore Duval's improved grooving plane (pat. 97,177) was "to produce in one tool all that is required to form grooves of several different widths." None was more appealing than Daniel D. Whitker's saw-rabbet plane (pat. 52,478) which combined "an adjustable saw with an adjustable fence or gage, both being attached to a stock with handle similar to a plane, forming together a tool combining the properties of the joiner's plow and fillister" (fig. 61). Nor was Whitker's idea simply a drawing-board exercise. It was produced commercially and was well advertised, as seen in the circular reproduced in figure 62.

Figure 60.—1857: In a variety of arrangements, the

addition of metal plates, caps, and screws at the mouth of the plane, as

shown in Thomas Worrall's drawing, proved a transitional device that

preserved the ancient shape of the tool and slowed the introduction of

bench planes made entirely of iron. (Wash drawing from U.S. Patent

Office, June 23, 1857, Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 60.—1857: In a variety of arrangements, the

addition of metal plates, caps, and screws at the mouth of the plane, as

shown in Thomas Worrall's drawing, proved a transitional device that

preserved the ancient shape of the tool and slowed the introduction of

bench planes made entirely of iron. (Wash drawing from U.S. Patent

Office, June 23, 1857, Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 61.—1865: Not all multipurpose innovations

resulted from the use of new materials. Daniel D. Whitker patented a

combination saw and rabbet plane little different from one illustrated

by André-Jacob Roubo in his L'Art du menuisier in 1769. (Wash drawing

from U.S. Patent Office, October 4, 1865, Record Group 241, the National

Archives.)

Figure 61.—1865: Not all multipurpose innovations

resulted from the use of new materials. Daniel D. Whitker patented a

combination saw and rabbet plane little different from one illustrated

by André-Jacob Roubo in his L'Art du menuisier in 1769. (Wash drawing

from U.S. Patent Office, October 4, 1865, Record Group 241, the National

Archives.)

In sum, these ideas produced a major break with the traditional shape of the bench plane. William Foster in 1843 (pat. 3,355), Birdsill Holly in 1852 (pat. 9,094), and W.S. Loughborough in 1859 (pat. 23,928) are particularly good examples of the radical departure from the wooden block. And, in the period after the Civil War, C.G. Miller (discussed on p. 213 and in fig. 63), B.A. Blandin (fig. 64), and Russell Phillips (pat. 106,868) patented multipurpose metallic bench planes of excellent design. It should be pointed out that the patentees mentioned above represent only a few of the great number that tried to improve the plane. Only the trend of change is suggested by the descriptions and illustrations presented here. The cumulative effect awaited a showcase, and the planemakers found it at the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 held in Philadelphia.

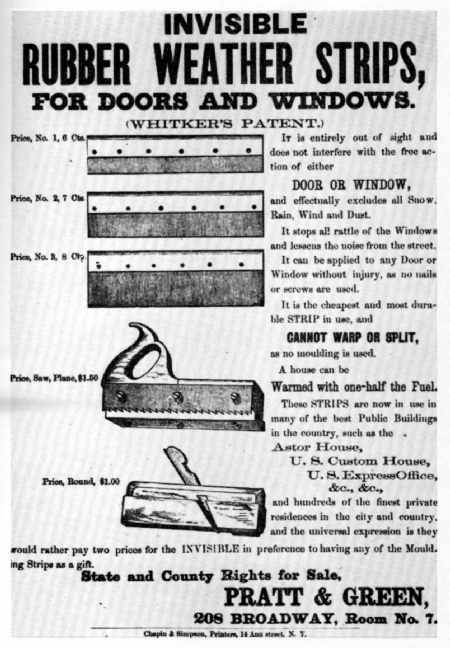

Figure 62.—About 1865: The progress of an idea from an

18th-century encyclopedia through an American patentee to commercial

reality can be seen in this flier advertising Whitker's saw-rabbet.

(Smithsonian Institution Library. Smithsonian photo 56629.)

Figure 62.—About 1865: The progress of an idea from an

18th-century encyclopedia through an American patentee to commercial

reality can be seen in this flier advertising Whitker's saw-rabbet.

(Smithsonian Institution Library. Smithsonian photo 56629.)

The impact of these new planes at the Exhibition caused some retrospection among the judges:

The planes manufactured in Great Britain and in other countries fifty years ago were formed of best beech-wood; the plane irons were of steel and iron welded together; the jointer plane, about 21 inches long, was a bulky tool; the jack and hand planes were of the same materials. Very little change has been made upon the plane in Great Britain, unless in the superior workmanship and higher quality of the plane iron.[19]

The solid wood-block plane, varying from country to country only in the structure of its handles and body decoration, had preserved its integrity of design since the Middle Ages. At the Centennial, however, only a few examples of the old-type plane were exhibited. A new shape dominated the cases. Designated by foreign observers as the American plane, it received extended comment. Here was a tool