constructed with a skeleton iron body, having a curved wooden handle; the plane iron is of the finest cast-steel; the cover is fitted with an ingenious trigger at the top, which, with a screw below the iron, admits of the plane iron being removed for sharpening and setting without the aid of the hammer, and with the greatest ease. The extensive varieties of plane iron in use are fitted for every requirement; a very ingenious arrangement is applied to the tools for planing the insides of circles or other curved works, such as stair-rails, etc. The sole of the plane is formed of a plate of tempered steel about the thickness of a handsaw, according to the length required, and this plate is adapted to the curve, and is securely fixed at each end. With this tool the work is not only done better but in less time than formerly. In some exhibits the face of the plane was made of beech or of other hard wood, secured by screws to the stock, and the tool becomes a hybrid, all other parts remaining the same as in the iron plane.[20]

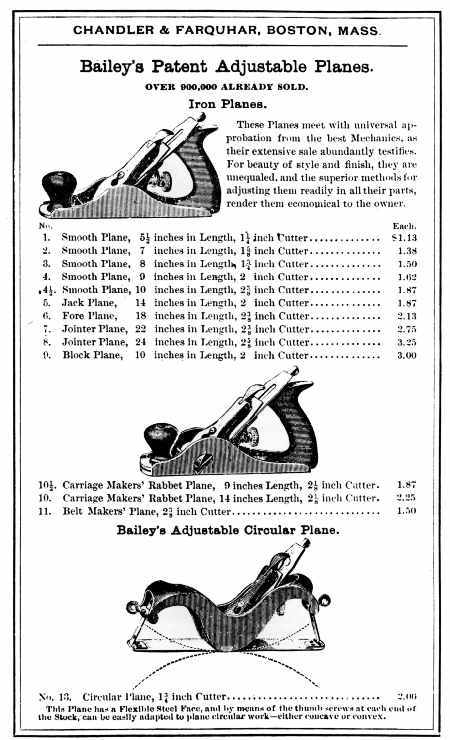

The popularity of Bailey's patented planes (fig. 65), the type so praised above, was by no means transitory. In 1884 the Boston firm of Goodnow & Wightman, "Importers, Manufacturers and Dealers in Tools of all kinds," illustrated the several planes just described and assured prospective buyers that

These tools meet with universal approbation from the best Mechanics. For beauty of style and finish they are unequalled, and the great convenience in operating renders them the cheapest Planes in use; they are SELF-ADJUSTING in every respect; and each part being made INTERCHANGEABLE, can be replaced at a trifling expense.[21]

By 1900 an advertisement for Bailey's planes published in the catalogue of another Boston firm, Chandler and Farquhar, indicated that "over 900,000" had already been sold.[22]

Other mass-produced edge tools—axes, adzes, braces and bits, augers, saws, and chisels—illustrated in the trade literature of the toolmakers became, as had the iron-bodied bench plane, standard forms. In the last quarter of the 19th century the tool catalogue replaced Moxon, Duhamel, Diderot, and the builders' manuals as the primary source for the study and identification of hand tools. The Centennial had called attention to the superiority of certain American tools and toolmakers. The result was that until the end of the century, trade literature faithfully drummed the products that had proven such "an attraction to the numerous artisans who visited the Centennial Exhibition from the United States and other countries."[23]

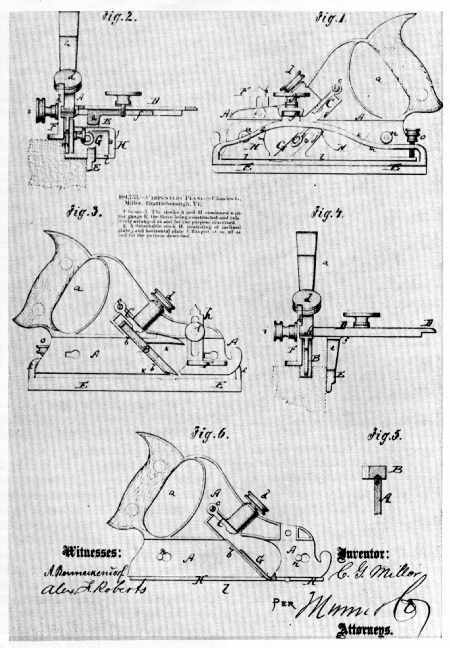

Figure 63.—1870: The metallic version of the plow plane

later produced by Stanley and Company was patented by [Charles] G.

Miller as a tool readily "convertible into a grooving, rabbeting, or

smoothing plane." In production this multipurpose plow gained an

elaborate decoration (fig. 51) nowhere suggested in Miller's

specification. (Wash drawing from U.S. Patent Office, June 28, 1870,

Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

Figure 63.—1870: The metallic version of the plow plane

later produced by Stanley and Company was patented by [Charles] G.

Miller as a tool readily "convertible into a grooving, rabbeting, or

smoothing plane." In production this multipurpose plow gained an

elaborate decoration (fig. 51) nowhere suggested in Miller's

specification. (Wash drawing from U.S. Patent Office, June 28, 1870,

Record Group 241, the National Archives.)

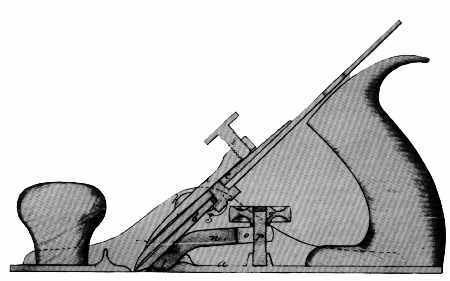

Figure 64.—1867: The drawing accompanying B.A. Blandin's

specification for an "Improvement in Bench Planes" retained only the

familiarly shaped handle or tote of the traditional wood-bodied plane.

This new shape rapidly became the standard form of the tool with later

variations chiefly related to the adjustability of the plane-iron and

sole. (Wash drawing from U.S. Patent Office, May 7, 1867, Record Group

241, the National Archives.)

Figure 64.—1867: The drawing accompanying B.A. Blandin's

specification for an "Improvement in Bench Planes" retained only the

familiarly shaped handle or tote of the traditional wood-bodied plane.

This new shape rapidly became the standard form of the tool with later

variations chiefly related to the adjustability of the plane-iron and

sole. (Wash drawing from U.S. Patent Office, May 7, 1867, Record Group

241, the National Archives.)

Collins and Company of New York City had been given commendation for the excellence of their axes; through the end of the century, Collins' brand felling axes, broad axes, and adzes were standard items, as witness Hammacher, Schlemmer and Company's catalogue of 1896.[24] Disston saws were a byword, and the impact of their exhibit at Philadelphia was still strong, as judged from Baldwin, Robbins' catalogue of 1894. Highly recommended was the Disston no. 76, the "Centennial" handsaw with its "skew back" and "apple handle." Jennings' patented auger bits were likewise standard fare in nearly every tool catalogue.[25] So were bench planes manufactured by companies that had been cited at Philadelphia for the excellence of their product; namely, The Metallic Plane Company, Auburn, New York; The Middletown Tool Company, Middletown, Connecticut; Bailey, Leonard, and Company, Hartford; and The Sandusky Tool Company, Sandusky, Ohio.[26]

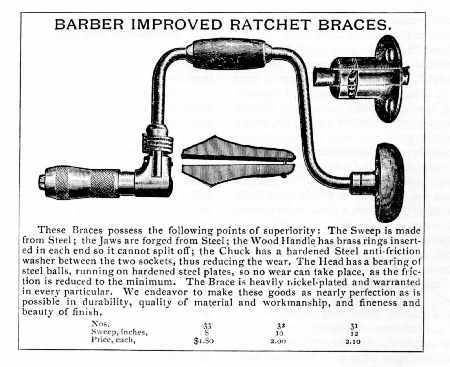

An excellent indication of the persistence of the Centennial influence, and of the tool catalogue as source material, is seen in Chandler and Farquhar's illustrated pamphlet of 1900. Their advertisement for Barber's improved ratchet brace (fig. 66), a tool much admired by the Centennial judges, amply illustrates the evolution of design of a basic implement present in American society since the first years of settlement. The Barber brace represents the ultimate sophistication of a tool, achieved through an expanded industrial technology rather than by an extended or newly found use for the device itself. It is a prime example of the transition of a tool from Moxon to its perfected form in the 20th century:

These Braces possess the following points of superiority: The Sweep is made from Steel; the Jaws are forged from Steel; the Wood Handle has brass rings inserted in each end so it cannot split off; the Chuck has a hardened Steel antifriction washer between the two sockets, thus reducing the wear. The Head has a bearing of steel balls, running on hard steel plates, so no wear can take place, as the friction is reduced to the minimum. The Brace is heavily nickel-plated and warranted in every particular. We endeavor to make these goods as nearly perfection as is possible in durability, quality of material and workmanship, and fineness and beauty of finish.[27]

Figure 65.—1900: American planemakers had been cited at

the Philadelphia Centennial as having introduced a dramatic change in

the nature of the tool. Although wood-bodied planes continued to be

used, they were outdated and in fact anachronistic by the close of the

19th century. From the 1870's forward, it was the iron-bodied plane,

most frequently Bailey's, that enlivened the trade literature.

(Catalogue of Chandler and Farquhar, Boston, 1900. Smithsonian photo

55798.)

Figure 65.—1900: American planemakers had been cited at

the Philadelphia Centennial as having introduced a dramatic change in

the nature of the tool. Although wood-bodied planes continued to be

used, they were outdated and in fact anachronistic by the close of the

19th century. From the 1870's forward, it was the iron-bodied plane,

most frequently Bailey's, that enlivened the trade literature.

(Catalogue of Chandler and Farquhar, Boston, 1900. Smithsonian photo

55798.)

Figure 66.—1900: Few tools suggest more clearly the

influence of modern industrial society upon the design and construction

of traditional implements than Barber's ratchet brace. It is not without

interest that as the tools of the wood craftsman became crisply

efficient, his work declined correspondingly in individuality and

character. The brace and the plane, as followed from Moxon through the

trade literature of the late 19th century, achieved perfection in form

and operation at a time when their basic functions had been usurped by

machines. (Catalogue of Chandler and Farquhar, Boston, 1900. Smithsonian

photo 56626.)

Figure 66.—1900: Few tools suggest more clearly the

influence of modern industrial society upon the design and construction

of traditional implements than Barber's ratchet brace. It is not without

interest that as the tools of the wood craftsman became crisply

efficient, his work declined correspondingly in individuality and

character. The brace and the plane, as followed from Moxon through the

trade literature of the late 19th century, achieved perfection in form

and operation at a time when their basic functions had been usurped by

machines. (Catalogue of Chandler and Farquhar, Boston, 1900. Smithsonian

photo 56626.)

The description of Barber's brace documents a major technical change: wood to steel, leather washers to ball bearings, and natural patina to nickel plate. It is also an explanation for the appearance and shape of craftmen's tools, either hand forged or mass produced. In each case, the sought-after result in the form of a finished product has been an implement of "fineness and beauty." This quest motivated three centuries of toolmakers and brought vitality to hand-tool design. Moxon had advised:

He that will a good Edge win,

Must Forge thick and Grind thin.[28]

If heeded, the result would be an edge tool that assured its owner "ease and delight."[29] Throughout the period considered here, the most praiseworthy remarks made about edge tools were variations of either "unsurpassed in quality, finish, and beauty of style" or, more simply, commendation for "excellent design and superior workmanship."[30] The hand tool thus provoked the same value words in the 19th as in the 17th century.

The aesthetics of industrial art, whether propounded by Moxon or by an official at the Philadelphia Centennial, proved the standard measure by which quality could be judged. Today these values are particularly valid when applied to a class of artifacts that changed slowly and have as their prime characteristics anonymity of maker and date. With such objects the origin, transition, and variation of shape are of primary interest. Consider the common auger whose "Office" Moxon declared "is to make great round holes" and whose importance was so clearly stressed at Philadelphia in 1876.[31] Neither its purpose nor its gross appearance (a T-handled boring tool) had changed. The tool did, however, develop qualitatively through 200 years, from a pod or shell to a spiral bit, from a blunt to a gimlet point, and from a hand-fashioned to a geometrically exact, factory-made implement: innovations associated with Cooke (1770), L'Hommedieu (1809), and Jennings (1850's). In each instance the tool was improved—a double spiral facilitated the discharge of shavings, a gimlet point allowed the direct insertion of the auger, and machine precision brought mathematical accuracy to the degree of twist. Still, overall appearance did not change. At the Centennial, Moxon would have recognized an auger, and, further, his lecture on its uses would have been singularly current. The large-bore spiral auger still denoted a mortise, tenon, and trenail mode of building in a wood-based technology; at the same time its near cousin, the wheelwright's reamer, suggested the reliance upon a transport dependent upon wooden hubs. The auger in its perfected form—fine steel, perfectly machined, and highly finished—contrasted with an auger of earlier vintage will clearly show the advance from forge to factory, but will indicate little new in its method of use or its intended purpose.

Persons neither skilled in the use of tools nor interested in technical history will find that there is another response to the common auger, as there was to the upholsterer's hammer, the 18th-century brace, or the saw with the custom-fitted grip. This is a subjective reaction to a pleasing form. It is the same reaction that prompted artists to use tools as vehicles to help convey lessons in perspective, a frequent practice in 19th-century art manuals. The harmony of related parts—the balance of shaft and handle or the geometry of the twist—makes the auger a decorative object. This is not to say that the ancient woodworker's tool is not a document attesting a society's technical proficiency—ingenuity, craftsmanship, and productivity. It is only to suggest again that it is something more; a survival of the past whose intrinsic qualities permit it to stand alone as a bridge between the craftsman's hand and his work; an object of considerable appeal in which integrity of line and form is not dimmed by the skill of the user nor by the quality of the object produced by it.

In America, this integrity of design is derived from three centuries of experience: one of heterogeneous character, the mid-17th to the mid-18th; one of predominately English influence, from 1750 to 1850; and one that saw the perfection of basic tools, by native innovators, between 1850 and the early 20th century. In the two earlier periods, the woodworking tool and the products it finished had a natural affinity owing largely to the harmony of line that both the tool and finished product shared. The later period, however, presents a striking contrast. Hand-tool design, with few exceptions, continued vigorous and functional amidst the confusion of an eclectic architecture, a flurry of rival styles, the horrors of the jigsaw, and the excesses of Victorian taste. In conclusion, it would seem that whether seeking some continuous thread in the evolution of a national style, or whether appraising American contributions to technology, such a search must rest, at least in part, upon the character and quality of the hand tools the society has made and used, because they offer a continuity largely unknown to other classes of material survivals.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] W.M. Flinders Petrie, "History in Tools," Annual Report Smithsonian Institution, 1918, pp. 563–572 [reprint].

[2] Johann Amos Comenius, Orbis Sensualium Pictus, transl. Charles Hoole (London, 1685), pp. 130, 143.

[3] Joseph Moxon, Mechanick Exercises or the Doctrine of Handy-Works, 3rd. ed. (London, 1703), pp. 63, 119.

[4] Martin, Circle of the Mechanical Arts (1813), p. 123.

[5] Peter Nicholson, The Mechanic's Companion (Philadelphia, 1832), pp. 31, 89–90.

[6] Catalog, Book 87, Cutler and Co., Castle Hill Works, Sheffield [in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London]; and Illustrated Supplement to the Catalogue of Bench Planes, Arrowmammett Works (Middletown, Conn., 1857) [in the Smithsonian Institution Library].

[7] York County Records, Virginia Deeds, Orders, and Wills, no. 13 (1706–1710), p. 248; and the inventory of Amasa Thompson in Lawrence B. Romaine, "A Yankee Carpenter and His Tools," The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association (July 1953), vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 33–34.

[8] Reports by the Juries: Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, 1851 (London, 1852), p. 485.

[9] U.S. patent specifications cited in this paragraph may be found at the U.S. Patent Office, Washington, D.C.

[10] In 1865 George Parr in his application for an improved screwdriver stated categorically that the scalloped blade served no purpose other than decoration. See U.S. patent 45,854, dated January 10, 1865.

[11] Francis A. Walker, ed., United States Centennial Commission, International Exhibition, 1876, Reports and Awards, Group XV (Philadelphia, 1877), p. 5.

[12] Ibid., p. 6.

[13] Ibid., pp. 9–10.

[14] Ibid., pp. 11–12.

[15] Ibid., pp. 14, 44, 5.

[16] Ibid., p. 13.

[17] Restored patent 4,859X, August 24, 1827, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

[18] U.S. pat. 16,889, U.S. Patent Office, Washington, D.C. The numbered specifications that follow may be found in the same place.

[19] Walker, ed., Reports and Awards, group 15, p. 13.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Tools (Boston, 1884), p. 54 [in the Smithsonian Institution Library].

[22] Tools and Supplies (June 1900), no. 85 [in the Smithsonian Institution Library].

[23] Walker, op. cit. (footnote 19), p. 14.

[24] Tools for All Trades (New York, 1896), item 75 [in the Smithsonian Institution Library].

[25] See Baldwin, Robbins & Co.: Illustrated Catalogue (Boston, 1894), pp. 954, 993 [in the Smithsonian Institution Library].

[26] Walker, op. cit. (footnote 19), p. 14.

[27] Tools and Supplies, op. cit. (footnote 22).

[28] Mechanick Exercise ..., p. 62.

[29] Ibid., p. 95.

[30] Walker, op. cit. (footnote 19), pp. 31–49.

[31] Mechanick Exercises ..., p. 94.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Book of trades, or library of the useful arts. 1st Amer. ed. Whitehall, N.Y., 1807.

Boy's book of trades. London, 1866.

The cabinetmaker in eighteenth-century Williamsburg. (Williamsburg Craft Series.)

Williamsburg, Va., 1963.

Comenius, Johann Amos. Orbis sensualium pictus. Transl. Charles Hoole. London,

1664, 1685, 1777, et al.

Cotter, John L. Archeological excavations at Jamestown, Virginia. (No. 4 in Archeological

Research Series.) Washington: National Park Service, 1958.

Diderot, Denis. L'encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers.

Paris, 1751–1765.

Early American Industries Association. Chronicle. Williamsburg, Va., 1933+.

Gillispie, Charles Coulston, ed. A Diderot pictorial encyclopedia of trades and industry.

New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1959.

Goodman, W.L. The history of woodworking tools. London: G. Bell and Sons, Ltd.,

1964.

Holtzapffel, Charles. Turning and mechanical manipulations. London [1846].

Knight, Edward Henry. Knight's American mechanical dictionary. New York, 1874–1876.

Martin, Thomas. The circle of the mechanical arts. London, 1813.

Mercer, Henry C. Ancient carpenters' tools. Doylestown, Pennsylvania: The Bucks

County Historical Society, 1951.

Moxon, Joseph. Mechanick exercises. 3rd ed. London, 1703.

Nicholson, Peter. The mechanic's companion. Philadelphia, 1832.

Petersen, Eugene T. Gentlemen on the frontier: A pictorial record of the culture of Michilimackinac.

Mackinac Island, Mich., 1964.

Petrie, Sir William Matthew Flinders. Tools and weapons illustrated by the Egyptian

collection in University College, London. London, 1917.

Roubo, André-Jacob. L'art du menuisier. (In Henri-Louis Duhamel du Monceau,

Descriptions des arts et métiers.) Paris, 1761–1788.

Sachs, Hans. Das Ständebuch: 114 Holzschnitte von Jost Amman, mit Reimen von Hans

Sachs. Leipzig: Insel-Verlag, 1934.

Singer, Charles, et al. A history of technology. 5 vols. New York and London:

Oxford University Press, 1954–1958.

Sloane, Eric. A museum of early American tools. New York: Wilfred Funk, Inc.,

1964.

Tomlinson, Charles. Illustrations of trades. 2nd ed. London, 1867.

Welsh, Peter C. "The Decorative Appeal of Hand Tools," Antiques, vol. 87, no. 2,

February 1965, pp. 204–207.

---- U.S. patents, 1790–1870: New uses for old ideas. Paper 48 in Contributions

from the Museum of History and Technology: Papers 45–53 (U.S. National

Museum Bulletin 241), by various authors; Washington: Smithsonian Institution,

1965.

Wildung, Frank H. Woodworking tools at Shelburne Museum. (No. 3 in Museum

Pamphlet Series.) Shelburne, Vermont: The Shelburne Museum, 1957.

U.S. Government Printing Office: 1966

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C., 20402—Price 70 cents

Paper 51, pages 178–228, from UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM BULLETIN

CONTRIBUTIONS FROM

THE MUSEUM OF HISTORY

AND TECHNOLOGY

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION · WASHINGTON, D.C.