CHAPTER VI. EARTHWORKS—THE MOUNDS.

In connection more or less intimate with the various earthworks already described, are the Tumuli or MOUNDS. Together, these two classes of remains constitute a single system of works, and are the monuments of the same people. And while the enclosures impress us with the number and power of the nations which built them, and enlighten us as to the amount of military knowledge and skill which they possessed, as well as, in some degree, in respect to the nature of their superstitions,—the mounds and their contents, as disclosed by the mattock and the spade, serve to reflect light more particularly upon their customs and the condition of the arts among them. Within these mounds we must look for the only authentic remains of their builders. They are the principal depositories of ancient art; they cover the bones of the distinguished dead of remote ages; and hide from the profane gaze of invading races the altars of the ancient people.

A simple heap of earth or stones seems to have been the first monument which suggested itself to man; the pyramid, the arch, and the obelisk are evidences of a more advanced state. But rude as are these primitive memorials, they have been but little impaired by time, while other more imposing structures have sunk into shapeless ruins. When covered with forests, and their surfaces interlaced with the roots of trees and bushes, or when protected by turf, the humble mound bids defiance to the elements which throw down the temple and crumble the marble into dust. We therefore find them, little changed from their original proportions, side by side with the ruins of those proud edifices which mark the advanced, as the former do the primitive state of the people who built them. They are scattered over p140 India; they dot the steppes of Siberia and the vast region north of the Black Sea; they line the shores of the Bosphorus and Mediterranean; they are found in old Scandinavia, and are singularly numerous in the British islands. In America, they prevail from the great lakes of the north, through the valley of the Mississippi, and the seats of semi-civilization in Mexico, Central America, and Peru, even to the waters of the La Plata on the south. We find them also on the shores of the Pacific ocean, near the mouth of the Columbia river, and on the Colorado of California. With the character of those abroad we have little, at present, to do, except perhaps to note some of the more striking features which they exhibit in common with those of our own valley.

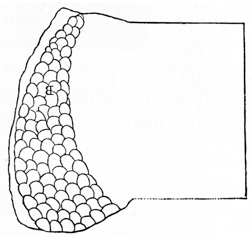

Allusion has already been made to the number and dimensions of the mounds of the West. To say that they are innumerable in the ordinary use of the term would be no exaggeration. They may literally be numbered by thousands and tens of thousands. In form, as observed in a preceding chapter, they are generally simple cones, frequently truncated and sometimes terraced. They are also elliptical, pear-shaped, or of a square pyramidal form,—in the last case always truncated, and most usually having one or more graded ascents to their summits. These varieties are partially illustrated in the cut at the head of this chapter, and will be amply exhibited in the pages which follow. No doubt can be entertained that their forms were, in great part, determined by the purposes for which they were designed, and may therefore be of use to us in ascertaining their character. Thus, if any were designed to serve as the sites of temples, or as “high places” for the performance of religious rites and ceremonies, it is evident they would be constructed with special reference to these objects.

In common with the enclosures, the mounds are for the most part composed of earth, though stone mounds are by no means rare. They are sometimes composed entirely of clay, while the soil all around them, for a long distance, is gravel or loam. The object of this may perhaps be found in the fact that mounds composed of such materials better resist the action of the elements, and preserve their form. There is certainly no difference in their position or contents which would justify the supposition that any peculiar dependence existed between the material composing the mound and the purposes to which it was devoted. Whether any significance may attach to the predominance of stone, in some of the mounds, is a question difficult to answer. It occasionally happens that a mound of stone occurs in the midst of a group composed of earth. Such was the case with one which formerly stood within the limits of Chillicothe. As a general rule, however, the mound is composed of material found upon the spot or taken from pits near by; and stone mounds oftenest occur where, from the hardness of the soil or the abundance of stones, it would be easiest to construct the tumulus of the latter material.

In respect to the position of the mounds, it may be said that those of Ohio occur mostly within or near enclosures; sometimes in groups, but oftener detached and isolated, and seldom with any degree of regularity in respect to each other. Such is believed to be the case generally throughout the entire valley of the Mississippi. A section of the Ohio valley, however, embraced between the mouths of the Guyandotte and Scioto rivers, an extent of sixty miles, which was p141 examined with special reference to this point, exhibited no works of magnitude in the form of enclosures; yet there was an abundance of mounds, though chiefly of small dimensions. Occasional groups of fifteen or twenty were noticed, sometimes occurring in lines, as if placed with design; a circumstance easily accounted for by the nature of the ground, which is here broken into long, low swells, or narrow ridges, with marshy intervals between them,—the mounds occupying the summits of the ridges.

On the tops of the hills, and on the jutting points of the table lands bordering the valleys in which the earthworks are found, mounds occur in considerable numbers. The most elevated and commanding positions are frequently crowned with them, suggesting at once the purposes to which some of the mounds or cairns of the ancient Celts were applied, that of signal or alarm posts. It is not unusual to find detached mounds among the hills back from the valleys and in secluded places, with no other monuments near. The hunter often encounters them in the depths of the forests, when least expected; perhaps overlooking some waterfall, or placed in some narrow valley where the foot of man seldom enters.

Thus much respecting the mounds could not escape observation, and has long been known; but beyond this our information has been extremely limited. And though partial excavations have been made at various times by different individuals, still nothing like a systematic exploration, sufficiently thorough and extensive to warrant any conclusion respecting them, has hitherto been attempted. The few detached observations which have met the light have been too vague, and in many cases too poorly authenticated, to enable the inquirer to make any satisfactory deductions from them.

The popular opinion, however, based in a great degree upon the well ascertained purposes of the barrows and tumuli occurring in certain parts of Europe and Asia, is that they are simple monuments, marking the last resting-place of some great p142 chief or distinguished individual, among the tribes of the builders. Some have supposed them to be the cemeteries, in which were deposited the dead of a tribe or a village for a certain period, and that the size of the mound is an indication of the number inhumed; others, that they mark the sites of great battles, and contain the bones of the slain. On all hands the opinion has been entertained, that they were devoted to sepulture alone. This received opinion is not, however, sustained by the investigations here recorded. The conclusion to which these researches have led, is, that the mounds were constructed for several grand and dissimilar purposes; or rather, that they are of different classes. The conditions upon which the classification is founded are four in number,—namely: position, form, structure, and contents. In this classification, we distinguish—

1st. ALTAR MOUNDS, which occur either within, or in the immediate vicinity of enclosures; which are stratified, and contain altars of burned clay or stone; and which were places of sacrifice.

2d. MOUNDS OF SEPULTURE, which stand isolated or in groups more or less remote from the enclosures; which are not stratified; which contain human remains; and which were the burial places and monuments of the dead.

3d. TEMPLE MOUNDS, which occur most usually within, but sometimes without the walls of enclosures; which possess great regularity of form; which contain neither altars nor human remains; and which were “High Places” for the performance of religious rites and ceremonies, the sites of structures, or in some way connected with the superstitions of the builders.

4th. ANOMALOUS MOUNDS, including mounds of observation and such as were applied to a double purpose, or of which the design and objects are not apparent. This division includes all which do not clearly fall within the preceding three classes.

These classes are broadly marked in the aggregate, though in some instances it is difficult to determine the character of the mounds which fall under notice. Of one hundred mounds examined, sixty were altar or temple mounds; twenty sepulchral; and twenty either places of observation or anomalous in their character. Such, however, is not the proportion in which they occur. From the fact that the altar or sacrificial mounds are most interesting and productive in relics, the largest number excavated was of that class. Excluding the temple mounds, which are not numerous, the remaining mounds of the Scioto valley are distributed between the three other varieties in very nearly equal proportions.

These general observations will serve to introduce plans and sections with accompanying descriptions of each of the above classes of mounds. The sections, for obvious reasons, are not drawn upon a uniform scale, nor are the relative proportions of the mounds always preserved; this however will result in no misunderstanding in any essential particulars. p143

ALTAR OR SACRIFICIAL MOUNDS.

-

The general characteristics of this class of mounds are:

1st. That they occur only within, or in the immediate vicinity of enclosures or sacred places.99 Of the whole number of mounds of this class which were examined, four only were found to be exterior to the walls of enclosures, and these were but a few rods distant from them.

2d. That they are stratified.

3d. That they contain symmetrical altars of burned clay or stone; on which are deposited various remains, which in all cases have been more or less subjected to the action of fire.

The fact of stratification, in these mounds, is one of great interest and importance. This feature has heretofore been remarked, but not described with proper accuracy; and has consequently proved an impediment to the recognition of the artificial origin of the mounds, by those who have never seen them. The stratification, so far as observed, is not horizontal, but always conforms to the convex outline of the mound.100 Nor does it resemble the stratification produced by the action of water, where the layers run into each other, but is defined with the utmost distinctness, and always terminates upon reaching the level of the surrounding earth. That it is artificial will, however, be sufficiently apparent after an examination of one of the mounds in which the feature occurs; for it would be difficult to explain, by what singular combination of “igneous and aqueous” action, stratified mounds were always raised over symmetrical monuments of burned clay or of stone.

The altars, or basins, found in these mounds, are almost invariably of burned clay, though a few of stone have been discovered. They are symmetrical, but not of uniform size and shape. Some are round, others elliptical, and others square, or parallelograms. Some are small, measuring barely two feet across, while others are fifty feet long by twelve or fifteen feet wide. The usual dimensions are from five to eight feet. All appear to have been modelled of fine clay brought to the spot from a distance, and they rest upon the original surface of the p144 earth. In a few instances, a layer or small elevation of sand had been laid down, upon which the altar was formed. The height of the altars, nevertheless, seldom exceeds a foot or twenty inches above the adjacent level. The clay of which they are composed is usually burned hard, sometimes to the depth of ten, fifteen, and even twenty inches. This is hardly to be explained by any degree or continuance of heat, though it is manifest that in some cases the heat was intense. On the other hand, a number of these altars have been noticed, which are very slightly burned; and such, it is a remarkable fact, are destitute of remains.

The characteristics of this class of mounds will be best explained, by reference to the accompanying illustrations. It should be remarked, however, that no two are precisely alike in all their details.

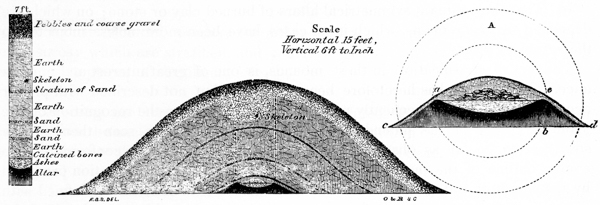

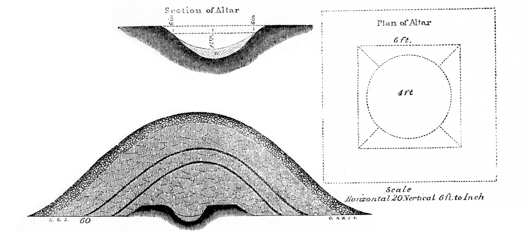

The mound, a section of which is here given, occurs in “Mound City,” a name given to a group of twenty-six mounds, embraced in one enclosure, on the banks of the Scioto river, three miles above the town of Chillicothe. (See Plate XIX, mound No. 1.) It is seven feet high by fifty-five feet base. A shaft, five feet square, was sunk from its apex, with the following results:

1st. Occurred a layer of coarse gravel and pebbles, which appeared to have been taken from deep pits surrounding the enclosure, or from the bank of the river. This layer was one foot in thickness.

-

Fig. 30.

Fig. 30.2d. Beneath this layer of gravel and pebbles, to the depth of two feet, the earth was homogeneous, though slightly mottled, as if taken up and deposited in small loads, from different localities. In one place appeared a deposit of dark-colored surface loam, and by its side, or covering it, there was a mass of the clayey soil from a greater depth. The outlines of these various deposits could be distinctly traced, as shown in Fig. 30.

3d. Below this deposit of earth, occurred a thin and even layer of fine sand, a little over an inch in thickness.

4th. A deposit of earth, as above, eighteen inches in depth.

5th. Another stratum of sand, somewhat thinner than the one above mentioned.

6th. Another deposit of earth, one foot thick; then—

7th. A third stratum of sand; below which was—

8th. Still another layer of earth, a few inches in thickness; which rested on—

9th. An altar, or basin, of burned clay. p145

This altar was perfectly round. Its form and dimensions are best shown by the supplementary plan and section A. The altar, measured from c to d, is nine feet in diameter; from a to e, five feet; height from b to e, twenty inches; dip of curve a r e, nine inches. The sides c a, e d, slope regularly at a given angle. The body of the altar is burned throughout, though in a greater degree within the basin, where it is so hard as to resist the blows of a heavy hatchet,—the instrument rebounding as if struck upon a rock. The basin, or hollow of the altar, was filled up evenly with fine dry ashes, intermixed with which were some fragments of pottery, of an excellent finish, and ornamented with tasteful carvings on the exterior. One of the vases, of elegant model, taken in fragments from this mound, has been very nearly restored, and will be further noticed in the chapter on the Pottery of the Mounds. A few convex copper discs, much resembling the bosses used upon harnesses, were also found.

Above the deposit of ashes, and covering the entire basin, was a layer of silvery or opaque mica, in sheets, overlapping each other; upon which, immediately over the centre of the basin, was heaped a quantity of burned human bones, probably the amount of a single skeleton, in fragments. The position of these is indicated in the section. The layers of mica and calcined bones, it should be remarked, to prevent misapprehension, were peculiar to this individual mound, and were not found in any other of the class.

It will be seen, by the section, that at a point about two feet below the surface of the mound, a human skeleton was found. It was placed a little to the left of the centre, with the head to the east, and was so much decayed as to render it impossible to extract a single bone entire. Above the skeleton, as shown in the section, the layer of earth and the outer stratum of gravel and pebbles were broken up and intermixed. Thus, while on one side of the shaft the strata were clearly marked, on the other they were confused. And, as this was the first mound of the class excavated, it was supposed, from this circumstance, that it had previously been opened by some explorer; and it had been decided to abandon it, when the skeleton was discovered. Afterwards the matter came to be fully understood. No relics were found with this skeleton.

It is a fact well known, that the existing tribes of Indians, though possessing no knowledge of the origin or objects of the mounds, were accustomed to regard them with some degree of veneration. It is also known, that they sometimes buried their dead in them, in accordance with their almost invariable custom of selecting elevated points and the brows of hills as their cemeteries. That their remains should be found in the mounds, is therefore a matter of no surprise. They are never discovered at any great depth, not often more than eighteen inches or three feet below the surface. Their position varies in almost every case: most of them are extended at length, others have a sitting posture, while others again seem to have been rudely thrust into their shallow graves without care or arrangement. Rude implements of bone and stone, and coarse vessels of pottery, such as are known to have been in use among the Indians at the period of the earliest European intercourse, occur with some of them, particularly with those of a more ancient date; while modern implements and ornaments, in some cases of p146 European origin, are found with the recent burials. The necessity, therefore, of a careful and rigid discrimination, between these deposits and those of the mound-builders, will be apparent. From the lack of such discrimination, much misapprehension and confusion have resulted. Silver crosses, gun-barrels, and French dial-plates, have been found with skeletons in the mounds; yet it is not to be concluded that the mound-builders were Catholics, or used fire-arms, or understood French. Such a conclusion would, nevertheless, be quite as well warranted, as some which have been deduced from the absolute identity of certain relics taken from the mounds, with articles known to be common among the existing tribes of Indians. The fact of remains occurring in the mounds, is in itself hardly presumptive evidence that they pertained to the builders. The conditions attending them can alone determine their true character. As a general rule, to which there are few exceptions, the only authentic and undoubted remains of the mound-builders are found directly beneath the apex of the mound, on a level with the original surface of the earth; and it may be safely assumed, that whatever deposits occur near the surface of the mounds, are of a date subsequent to their erection.

The French maintained an intercourse, from a very early period, with the Indian tribes of the West. In the way of barter or as presents they distributed amongst them vast quantities of ornaments and implements of various kinds; which, in accordance with the Indian custom, were buried with the possessor at his death. Nothing is therefore more common, in invading the humble sepulchre of the Indian, than to find by the side of his skeleton the copper kettle, the gun, hatchet, and simple ornaments, so valued in his life-time. The latter consist chiefly of small silver crosses and brooches; several of which are sometimes found accompanying a single skeleton.101

In the class of mounds now under consideration we have data that will admit of no doubt, whereby to judge of the origin, as well as of the relative periods, of the various deposits found in them. If the stratification already mentioned as characterizing them is unbroken and undisturbed, if the strata are regular and entire, it p147 is certain that whatever occurs beneath them was placed there at the period of the construction of the mound. But if, on the other hand, these strata are broken up, it is equally certain that the mound has been disturbed, and new deposits made, subsequent to its erection. It is in this view, that the fact of stratification is seen to be important, as well as interesting; for it will serve to fix, beyond all dispute, the origin of many singular relics, having a decisive bearing on some of the leading questions connected with American archæology. The thickness of the exterior layer of gravel, in mounds of this class, varies with the dimensions of the mound, from eight to twenty inches. In a very few instances, the layer, which may have been designed to protect the form of the mound, and which purpose it admirably subserves, is entirely wanting. The number and relative position of the sand strata are variable; in some of the larger mounds, there are as many as six of them, in no case less than one, most usually two or three.

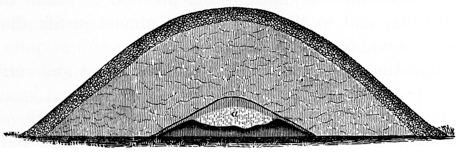

Fig. 31 exhibits a section of mound No. 2 in the plan of “Mound City.” This mound is ninety feet in diameter at the base by seven and a half feet high, being remarkably broad and flat. A shaft six feet square was sunk from the apex with the following results:

1st. Occurred the usual layer of gravel and pebbles, one foot thick.

2d. A layer of earth, three feet thick.

3d. A thin stratum of sand.

4th. Another layer of earth two feet thick.

5th. Another stratum of sand, beneath which, and separated by a few inches of earth, was—

6th. The altar, Fig. 32.

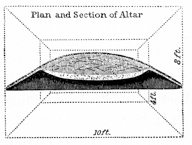

This altar was a parallelogram of the utmost regularity, as shown in the plan and section. At its base, it measures ten feet in length by eight in width; at the top, six feet by four. Its height was eighteen inches, and the dip of the basin nine inches. Within the basin was a deposit of fine ashes, unmixed with charcoal, three inches thick, much compacted by the weight of the superincumbent earth. Amongst the ashes were some fragments of pottery, also a few shell and pearl beads. Enough of the pottery was recovered to restore a beautiful vase, for a drawing and description of which the reader is referred to the paragraphs on Pottery. The second or p148 lower sand stratum in this, as in several other instances, rested directly upon the outer sides of the altar.

In this mound, three feet below the surface, were found two very well preserved skeletons, the presence of which was indicated, at the commencement of the excavation, by the interruption of the layers, as above described. They were placed side by side, the head of one resting at the elbow of the other. Under and about the heads of both were deposited some large rough fragments of greenstone, identical with that of which most of the stone implements of the former Indian tribes of the valley were made. There were also deposited with the skeletons many implements of stone, horn, and bone; among which was a beautiful chip of hornstone, about the size of the palm of one’s hand, which had manifestly been used for cutting purposes. There were several hand-axes and gouges of stone, and some articles made from the horns of the deer or elk, which resemble the handles of large knives; but no traces of iron or other metals were discoverable. Among the implements of bone was one formed from the shoulder-blade of the buffalo, in shape resembling a Turkish scimetar; also a singular notched instrument of bone, evidently intended for insertion in a handle, and designed, in common with similar articles in use by the Indians of the present day, for distributing the paint in lines and other ornamental figures on the faces of the warriors. Another instrument was also found, made by cutting off a section of the main stem of an elk’s horn, leaving one of the principal prongs attached; used perhaps as a hammer or war-club. Besides these there were some gouges made of elk’s horns, and a variety of similar relics; all of exceeding rudeness, and of no great antiquity. The skulls found in this mound possessed no marked features to distinguish them from the crania found in the known burial-places of the Shawanoes and other late Indian tribes.

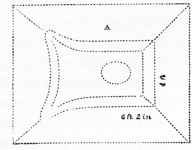

This mound, Fig. 33, is numbered 4 in the plan of “Mound City.” It is oblong in shape, measuring ninety by sixty feet base, and six feet in height. It has two sand strata, as shown in the section. The altar in this mound is remarkable from its depth, which is twenty-two inches, the hollow of the basin sinking a foot or more below the original surface of the soil. Its form and dimensions are best explained by the plan and section. Nothing was contained in the basin, except a white mass or layer five inches thick, a, presenting all the appearances of sharp p149 lime mortar. Mingled with this mass, which was hard and compact, were a few fragments of calcined shells; leading to the inference, that it was formed from the burning of shells. It was afterwards found upon analysis, that the mass was principally carbonate of lime, with a considerable portion of earthy particles, thus sustaining the inference already made. No fragments of bones, however small, were discoverable.

By the side of the mound just mentioned, the bases of the two running into each other, is another mound, No. 5 in the plan of “Mound City.” It is of the same form and dimensions with the one just described, and like that has two sand strata. The altar however more resembles that of Fig. 31, though somewhat smaller in size. It contained a quantity, perhaps thirty pounds in all, of galena in pieces weighing from two ounces to three pounds; also several lumps of fine clay, possessing an unctuous feel. The latter appeared to have originally formed a model over which a vessel of some sort had been fashioned. Around this deposit there was considerable charcoal, apparently of a light wood, but very little ashes. The altar, although the galena was but slightly burned, bore marks of intense heat,—thus evincing that it had been previously subjected for a considerable period, or at frequent intervals, to the action of fire.

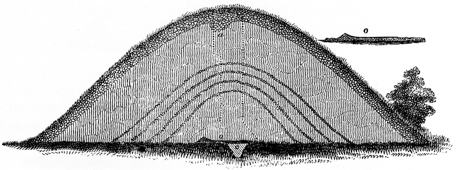

Fig. 34 is a section of the long mound, No. 3, in the plan of “Mound City.” For several reasons,—its shape, the great dimensions of its enclosed altar, and the number and variety of its relics,—this mound was minutely investigated, and is worthy of a detailed description. It is egg-shaped in form, and measures one hundred and forty feet in length, by fifty and sixty respectively at its greater and smaller ends, and is eleven feet high.

Its longitudinal bearing is N. 20° W. Four shafts were sunk at as many different points; between three of which, for a distance of over forty feet, connecting drifts were carried, as indicated in the plan.

The shaft a was first sunk. At the commencement of the excavation the feature already mentioned, viz. the confusion of the layers, was remarked, and care was accordingly taken to uncover carefully the expected recent deposit. This proved to be a single human skeleton, placed in a sitting posture, the head resting on the knees. The top of the skull was eighteen inches below the surface. The skeleton was well preserved, still retaining a large portion of its animal matter. The lower jaw was broken, a circumstance observed in most of the skeletons thus found. No relics were deposited with this skeleton. The sand strata occurred low down, following the curvature of the mound, as represented in the section.

Shaft c was next sunk. On the left side of the excavation a disturbance was p150 remarked; and at about two feet below the surface, a rude earthern vessel holding something over one quart, and the lower jaw of a human skeleton, were discovered. They were side by side, and seemed to have constituted the entire deposit.

Two sand strata occur in this mound, the first five feet below the surface, the second one foot deeper. The intermediate layers of earth presented the mottled appearance already explained, and were much compacted, rendering excavation exceedingly slow and laborious. The remaining shafts were afterwards sunk for the purpose of ascertaining the size and form of the altar, but disclosed nothing of importance in their course.

Fig. 35.—Longitudinal section of altar.

Although the altar in this mound was not fully exposed, yet enough was uncovered to ascertain very nearly its character and extent. Forty-five feet of its length was exposed, and in one place its entire width, which was eight feet across the top, by fifteen at the base. The portions in the section, extending beyond the line of the excavation, are supplied, giving an entire length to the altar of not far from sixty feet.

Fig. 36.—Cross section of altar.

By attention to the longitudinal section of the altar B C B, it will be seen that it shelves gradually from the ends, forming a basin of not far from eighteen inches in depth. The outer slope is more gradual than the inner one. Near the centre of the altar, two partitions, A A, are carried across it transversely, forming a minor basin or compartment, C, eight feet square. Within this basin the relics deposited in the mound were placed. The outer compartments seemed to have been filled with earth, previous to the final heaping over, so as to present a perfectly level surface, which had been slightly burned. This feature is indicated in the section, which also illustrates another interesting and important peculiarity. Upon penetrating the altar (a task of no little difficulty in consequence of its extreme hardness) to ascertain its thickness, it was found to be burned to the depth of twenty-two inches. This could hardly be accounted for by the application or continuance of any degree of heat from above, and was therefore the occasion of some surprise. A more minute examination furnished the explanation. It was found that one altar had been built upon another; as if one had been used for a time, until, from defect or other causes, it was abandoned, when another was recast upon it. This process, as shown in the section F E, had been repeated three times, the outline of each successive layer being so distinct as to admit of no doubt as to its cause. The partitions A A were constructed subsequently to the erection of the altar, as is evidenced from the fact that they were scarcely burned through, while the altar immediately beneath them was burned to great hardness. Scattered upon the deposit of earth filling the compartments D D, and resting upon p151 the slopes of the altar, were found the traces of a number of pieces of timber, four or five feet long, and six or eight inches thick. They had been somewhat burned, and the carbonized surface had preserved their casts in the hard earth, although the wood had entirely decayed. They had been heaped over while glowing, for the earth around them was slightly baked. In fact the entire hollow of the altar was covered with a thin layer of fine carbonaceous matter, much like that formed by the burning of leaves or straw. These pieces had been of nearly uniform length; and this circumstance, joined to the position in which they occurred in respect to each other and to the altar, would almost justify the inference that they had supported some funeral or sacrificial pile.

The remains found in this mound were, in their number and variety, commensurate with the labor and care bestowed on its construction. A quantity of pottery and many implements of copper and stone were deposited on the altar, intermixed with much coal and ashes. They had all been subjected to a strong heat, which had broken up most of those which could be thus affected by its action. A large number of spear-heads, as they have been termed, beautifully chipped out of quartz and manganese garnet, had been placed here; but, out of a bushel or two of fragments, four specimens only were recovered entire. One of them is faithfully figured under the head of “Implements.” A quantity of the raw material, from which they were manufactured, was also found, consisting of large fragments of quartz and of crystals of garnet. Some of these crystals had been of large size, certainly not less than three or four inches in diameter. A single arrow-point of obsidian was found; also a number of fine arrow-heads of limpid quartz. One of these was four inches in length, and all were finely wrought. Judging from the quantity of fragments, some fifty or a hundred of these were originally deposited on the altar. Among the fragments were some large thin pieces of the same material, shaped like the blade of a knife. Two copper gravers or chisels, one measuring six, the other eight inches in length, (see “Implements,”) also twenty or more tubes formed of thin strips of copper, an inch and a quarter long by three eighths of an inch diameter, (see “Ornaments,”) were found among the remains. A large quantity of pottery, much broken up, enough perhaps to have formed originally a dozen vessels of moderate size, was also discovered. Two vases have been very nearly restored. They resemble, in material and form, those already mentioned, and have similar markings on their exterior. (See “Pottery.”) Also a couple of carved pipes; one of which, of beautiful model and fine finish, is cut out of a stone closely resembling, if indeed not identical with, the Potomac marble, of which the columns of the hall of the House of Representatives at Washington are made. The other is a bold figure of a bird, resembling the toucan, cut in white limestone.

A portion of the contents of this mound were cemented together by a tufa-like substance of a gray color, resembling the scoriæ of a furnace, and of great hardness. It was at first supposed to be carbonate of lime gradually deposited, in the lapse of time, from the water percolating through the outer stratum of limestone gravel and pebbles. The quantity however, covering as it did a large part of the basin to the depth of an inch or two, weighed strongly against such a conclusion; and a subsequent analysis demonstrated that it was made up in part of phosphates. A p152 single fragment of partially calcined bone was found on the altar. It was the patella of the human skeleton.

Such were the more important features of this interesting mound. It is evident that the enclosed altar had been often used, and several times remodelled, before it was finally heaped over. Why this was at last done, upon what occasion, and with what strange ceremonies, are questions which will probably forever remain unanswered.

Fig. 37 is a section of mound No. 8 in “Mound City.” In the number and

value of its relics, this mound far exceeds any hitherto explored.

It is small in

size, and in its structure exhibits nothing remarkable.

It had but one sand stratum,

Fig. 38.—Plan of altar.

the edges of which rested on the outer slopes of the altar,

as shown in the section. Between this stratum and the

deposit in the basin occurred a layer, a few inches thick,

of burned loam. The altar itself (Fig. 38) was somewhat

singular, though quite regular in shape. In

length it was six feet two inches, in width four feet.

At the point indicated in the section was a depression

of perhaps six inches below the general level of the

basin.

Fig. 38.—Plan of altar.

the edges of which rested on the outer slopes of the altar,

as shown in the section. Between this stratum and the

deposit in the basin occurred a layer, a few inches thick,

of burned loam. The altar itself (Fig. 38) was somewhat

singular, though quite regular in shape. In

length it was six feet two inches, in width four feet.

At the point indicated in the section was a depression

of perhaps six inches below the general level of the

basin.

The deposit (a) in this altar was large. Intermixed with much ashes, were found not far from two hundred pipes, carved in stone, many pearl and shell beads, numerous discs, tubes, etc., of copper, and a number of other ornaments of copper, covered with silver, etc. etc. The pipes were much broken up,—some of them calcined by the heat, which had been sufficiently strong to melt copper, masses of which were found fused together in the centre of the basin. A large number have nevertheless been restored, at the expense of much labor and no small amount of patience. They are mostly composed of a red porphyritic stone, somewhat resembling the pipe stone of the Coteau des Prairies, excepting that it is of great hardness and interspersed with small variously colored granules. The fragments of this material which had been most exposed to the heat were changed to a brilliant black color, resembling Egyptian marble. Nearly all the articles carved in limestone, of which there had been a number, were calcined.

The bowls of most of the pipes are carved in miniature figures of animals, birds, reptiles, etc. All of them are executed with strict fidelity to nature, and with exquisite skill. Not only are the features of the various objects represented faithfully, but their peculiarities and habits are in some degree exhibited. The otter is shown in a characteristic attitude, holding a fish in his mouth; the heron also holds p153 a fish; and the hawk grasps a small bird in its talons, which it tears with its beak. The panther, the bear, the wolf, the beaver, the otter, the squirrel, the raccoon, the hawk, the heron, crow, swallow, buzzard, paroquet, toucan, and other indigenous and southern birds,—the turtle, the frog, toad, rattlesnake, etc., are recognized at first glance. But the most interesting and valuable in the list, are a number of sculptured human heads, no doubt faithfully representing the predominant physical features of the ancient people by whom they were made. We have this assurance in the minute accuracy of the other sculptures of the same date. For engravings of these as well as of a large series of the other relics here mentioned, the reader is referred to the passages on “Sculptures.” Appropriate notices of the remaining articles discovered in this mound,—the copper discs and tubes, pearl, shell, and silver beads, etc.,—will be found under the head of “Ornaments.”

Fig. 39 is a section of mound No. 18 in “Mound City.” It has three sand

strata, and an altar of the usual form and dimensions. This altar contained no

relics, but was thinly covered with a carbonaceous deposit, resembling burned

leaves. The feature of this mound most worthy of remark was a singular burial

by incremation, which had been made in it at some period subsequent to its erection.

The indications (so often remarked as to need no further specification here) that

the mound had been disturbed were observed at the commencement of the excavation.

Fig. 40.

At the depth of four and a half feet, the deposit

was reached (Fig. 41). A quantity of water-worn stones,

about the size of common paving stones, and evidently taken

from the river close by, had been laid down, forming a rude

pavement six feet long by four broad. Lying diagonally

upon this pavement, as shown in Fig. 40, with its head

to the north-west, was a skeleton. It was remarkably well

preserved, and retained much of its animal matter,—a fact

attributable in some degree to the antiseptic qualities of the

carbonaceous material surrounding it.102

A fire had been built

over the body after it was deposited, its traces being plainly visible on the stones,

all of which were slightly burned. A quantity of carbonaceous

matter, resembling p154

that formed by the sudden covering up of burning twigs or other light materials,

covered the pavement and the skeleton. There were no relics with the skeleton;

although around its head were disposed a number of large fragments of sienite,

identical with that of which many of the instruments of the modern Indians are

known to have been made, previous and for some time subsequent to the introduction

of iron amongst them. After the burial had been performed, and the hole

partly filled, another fire had been kindled, burning the earth of a reddish color,

and leaving a distinctly marked line, as indicated in the section. The hole had

then been completely filled up, so as to leave a scarcely perceptible depression in

the mound.

Fig. 40.

At the depth of four and a half feet, the deposit

was reached (Fig. 41). A quantity of water-worn stones,

about the size of common paving stones, and evidently taken

from the river close by, had been laid down, forming a rude

pavement six feet long by four broad. Lying diagonally

upon this pavement, as shown in Fig. 40, with its head

to the north-west, was a skeleton. It was remarkably well

preserved, and retained much of its animal matter,—a fact

attributable in some degree to the antiseptic qualities of the

carbonaceous material surrounding it.102

A fire had been built

over the body after it was deposited, its traces being plainly visible on the stones,

all of which were slightly burned. A quantity of carbonaceous

matter, resembling p154

that formed by the sudden covering up of burning twigs or other light materials,

covered the pavement and the skeleton. There were no relics with the skeleton;

although around its head were disposed a number of large fragments of sienite,

identical with that of which many of the instruments of the modern Indians are

known to have been made, previous and for some time subsequent to the introduction

of iron amongst them. After the burial had been performed, and the hole

partly filled, another fire had been kindled, burning the earth of a reddish color,

and leaving a distinctly marked line, as indicated in the section. The hole had

then been completely filled up, so as to leave a scarcely perceptible depression in

the mound.

Fig. 41 is a section of mound No. 7 in “Mound City.” This mound is much the

largest within the enclosure, measuring seventeen and a half feet in height by ninety

feet base. From its top a full view of the entire group is commanded. A shaft

nine feet square was sunk from the apex. The outer layer of gravel, which in

this case was twenty inches thick, was found to be broken up, and at the depth

of three feet (at a point indicated by a in the section) were found two copper

axes, weighing respectively two, and two and one fourth pounds. At the depth of

seven feet occurred the first sand stratum, below which, at intervals of little more

than a foot, were three more,—four in all. At the depth of nineteen feet was found

a smooth level floor of clay,

Fig. 42.

slightly burned, which was covered with a thin layer

of sand an inch in thickness. This sand had a marked ferruginous

appearance,

and seemed to be cemented together, breaking up into large fragments a foot or

two square. At one side of the shaft, and resting on the sand, was noticed a

layer of silvery mica, as shown in the plan of the

excavation, Fig. 42. It was formed of round sheets,

ten inches or a foot in diameter, overlapping each

other like the scales of a fish. Lateral excavations

were made to determine its extent, with the result

indicated in the plan. The portion uncovered exhibited

something over one half of a large and regular

crescent, the outer edge of which rested on an elevation

or ridge of sand six inches in height, as shown

in the supplementary section o. The entire

length of p155

the crescent from horn to horn could not have been less than twenty feet, and its

greatest width five. The clay floor of this mound was but a few inches in thickness;

a small shaft, c, was sunk three feet below it, but it disclosed only a mass

of coarse ferruginous sand. The earth composing the mound was incredibly compact,

rendering excavation exceedingly slow and laborious. Two active men were

employed more than a week in making the excavation here indicated. It is not

absolutely certain that the mound was raised over the simple deposit above

mentioned, and it may yet be subjected to a more rigid investigation.

Fig. 42.

slightly burned, which was covered with a thin layer

of sand an inch in thickness. This sand had a marked ferruginous

appearance,

and seemed to be cemented together, breaking up into large fragments a foot or

two square. At one side of the shaft, and resting on the sand, was noticed a

layer of silvery mica, as shown in the plan of the

excavation, Fig. 42. It was formed of round sheets,

ten inches or a foot in diameter, overlapping each

other like the scales of a fish. Lateral excavations

were made to determine its extent, with the result

indicated in the plan. The portion uncovered exhibited

something over one half of a large and regular

crescent, the outer edge of which rested on an elevation

or ridge of sand six inches in height, as shown

in the supplementary section o. The entire

length of p155

the crescent from horn to horn could not have been less than twenty feet, and its

greatest width five. The clay floor of this mound was but a few inches in thickness;

a small shaft, c, was sunk three feet below it, but it disclosed only a mass

of coarse ferruginous sand. The earth composing the mound was incredibly compact,

rendering excavation exceedingly slow and laborious. Two active men were

employed more than a week in making the excavation here indicated. It is not

absolutely certain that the mound was raised over the simple deposit above

mentioned, and it may yet be subjected to a more rigid investigation.

Although this mound is classed as a mound of sacrifice, it presents some features peculiar to itself. Were we to yield to the temptation to speculation which the presence of the mica crescent holds out, we might conclude that the mound-builders worshipped the moon, and that this mound was dedicated, with unknown rites and ceremonies, to that luminary. It may be remarked that some of the mica sheets were of that peculiar variety known as “hieroglyphic” or “graphic mica.”