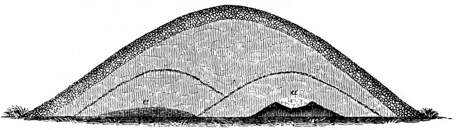

Fig. 43 is a section of mound No. 9, in the plan of the great work on the North fork of Paint creek (Plate X). It will be seen that this mound has several peculiar features. The altar, a, instead of occupying the centre, is placed considerably towards one side, and a layer of charcoal, c, fills the corresponding opposite side. Over the altar curves a stratum of sand, and over the layer of charcoal still another, as exhibited in the section. This altar was the smallest met with. It was round, not measuring more than two feet across the top. It was nevertheless rich in remains. Within it were found—

1st. Several instruments of obsidian. They were considerably broken up, but have been so much restored, as to exhibit pretty nearly their original form. Too large for arrow-heads, and too thin and slender for points of spears, they seem to have been designed for cutting purposes.

2d. Several scrolls tastefully cut from thin sheets of mica. They are perforated with small holes, as if they had been attached as ornaments to a robe of some description.

3d. Traces of cloth; small portions of which, though completely carbonized, were found, still retaining the structure of the thread. This appeared to have been made of some fine vegetable fibre. It was what is technically termed “doubled and twisted,” and was about the size of fine pack-thread.

4th. A considerable number of ivory or bone needles, or graving-tools, about one tenth of an inch thick. Their original length is not known. Several fragments were found two and three inches long. Some have flat cutting points, the points of others were round and sharp; some were straight, others slightly bent. p156

5th. A quantity of pearl beads; an article resembling the cover of a small vessel, carved from stone; also some fragments of copper, in thin narrow slips.

There were no relics of any kind found amongst the charcoal. The layer of this material was not far from six feet square. It had been heaped over while burning.

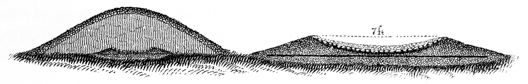

Fig. 44 is a section of a large mound, No. 5, in the same enclosure. In this instance the altar was covered with stones; and instead of the usual sand stratum, there was found a layer of large flat stones, corresponding to it. The altar, A, was composed of earth elevated two and a half feet above the original level of the soil, and was five feet long by three feet four inches broad, the sides sloping at an angle of nearly thirty degrees. It was faced on the top and on the sides with slabs of stone, quite regular in form and thickness, and which, although not cut by any instrument, were closely fitted together, as shown in the supplementary section of the altar, A. The stone is the Waverley sandstone, underlying the coal series, thin strata of which cap the hills bordering these valleys. The altar bore the marks of fire; and a few fragments of the mound-builders’ ornaments, a few pearl beads, etc., were found on and around it. The original deposit had probably been removed by the modern Indians, who had opened the mound and buried one of their dead on the slope of the altar. The stones composing the layer corresponding to the sand stratum were two or three deep, presenting the appearance of a wall which had fallen inwards.

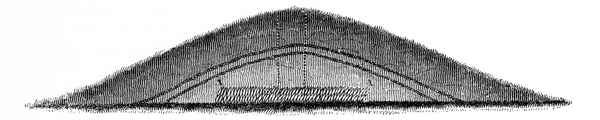

In the centre of the large enclosure, Plate XIX, is a solitary mound, of which a section is here presented, Fig. 45. It is now, after many years of cultivation, about five feet high by forty feet base. Like that last described, it has some novel features, although its purposes can hardly admit of a doubt. It has the casing of pebbles and gravel which characterize the altar-mounds, but has no sand layer, except a thin stratum resting immediately on the deposit contained in the altar. This altar is entirely peculiar. It seems to have been formed, at different intervals of time, as follows: first, a circular space, thirteen feet in diameter and eight inches in depth, was excavated in the original level of the plain; this was filled with fine sand, carefully levelled, and compacted to the utmost degree. Upon the level thus formed, which was perfectly horizontal, offerings by fire were made; at any rate a continuous heat was kept up, and fatty matter of some sort burned, for the sand to the depth of two inches is discolored, and to the depth of one inch is burned hard and black and cemented together. The ashes, etc., resulting from p157 this operation, were then removed, and another deposit of sand, of equal thickness with the former, was placed above it, and in like manner much compacted. This was moulded into the form represented in the plan, which is identical with that of the circular clay altars already described; the basin, in this instance, measuring seven feet in diameter by eight inches in depth. This basin was then carefully paved with small round stones, each a little larger than a hen’s egg, which were laid with the utmost precision, fully rivalling the pavior’s finest work. They were firmly bedded in the sand beneath them, so as to present a regular and uniform surface. Upon the altar thus constructed was found a burnt deposit, carefully covered with a layer of sand, above which was heaped the superstructure of the mound. The deposit consisted of a thin layer of carbonaceous matter, intermingled with which were some burned human bones, but so much calcined as to render recognition extremely difficult. Ten well wrought copper bracelets were also found, placed in two heaps, five in each, and encircling some calcined bones,—probably those of the arms upon which they were originally worn. Besides these were found a couple of thick plates of mica, placed upon the western slope of the altar.

Assuming, what must be very obvious from its form and other circumstances, that this was an altar and not a tomb, we are almost irresistibly led to the conclusion, that human sacrifices were practised by the race of the mounds. This conclusion is sustained by other facts, which have already been presented, and which need not be recapitulated here.

The two mounds last described are the only ones yet discovered possessing altars of stone; and, although it is likely there are others of similar construction, their occurrence must be very rare.

Such are the prevailing characteristics of this class of mounds. It will be remarked that while all have the same general features, no two are alike in their details. They differ in the number and relative position of their sand strata, as well as in the size and shape of their altars and the character of the deposits made on them. One mound covers a deposit made up almost entirely of pipes, another a deposit of spear-heads, or of galena or calcined shells or bones. In a few instances the symmetrical altar, of which so many examples have been given, is wanting, and its place is supplied by a level floor or platform of earth. Such was the case with mound No. 1, in the plan of the great work on the North fork of Paint creek, already referred to. This mound, although one of the richest in contents, was one of the smallest met with, being not over three feet in height. Its deposit was first disturbed by the plough, some years ago, and numerous singular articles were then taken from it. Upon investigation, in place of the altar, a level area ten or fifteen feet broad was found, much burned, on which the relics had been placed. These had been covered over with earth to perhaps the depth of a foot, followed by a stratum of small stones, and an outer layer of earth two feet in thickness. Hundreds of relics, and many of the most interesting and valuable hitherto found, were taken from this mound, among which may be mentioned several coiled serpents, carved in stone, and carefully enveloped in sheet mica and copper; p158 pottery; carved fragments of ivory; a large number of fossil teeth; numerous fine sculptures in stone, etc. Notice will be taken of some of the most remarkable of these, under the appropriate heads.

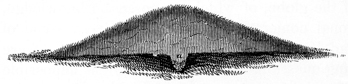

Another singular mound of somewhat anomalous character, of which a section is herewith given, (Fig. 46,) occurred in the same enclosure with the above. It is numbered 2 in Plate X, and is remarkable as being very broad and flat, measuring at least eighty feet in diameter by but six or seven in height. It has two sand strata; but instead of an altar, there are two layers of discs chipped out of hornstone, (A A of the section,) some nearly round, others in the form of spear-heads. They are of various sizes, but are for the most part about six inches long, by four wide, and three quarters of an inch or an inch in thickness. They were placed side by side, a little inclining, and one layer resting immediately on the other. Out of an excavation six feet long by four wide, not far from six hundred were thrown. The deposit extends beyond the limits of the excavation on every side. Supposing it to be twelve feet square, (and it may be twenty or thirty,) we have not far from four thousand of these discs deposited here. If they were thus placed as an offering, we can form some estimate, in view of the facts that they must have been brought from a great distance, and fashioned with great toil, of the devotional fervor which induced the sacrifice, or the magnitude of the calamity which that sacrifice was perhaps intended to avert. The fact, that this description of stone chips most easily when newly quarried, has induced the suggestion that the discs were deposited here for the purpose of protecting them from the hardening influence of the atmosphere, and were intended to be withdrawn and manufactured as occasion warranted or necessity required. It is incredible, however, that so much care should be taken to fashion the mound and introduce the mysterious sand strata, if it was designed to be disturbed at any subsequent period. There is little doubt that the deposit was final, and was made in compliance with some religious requirement. An excavation below these layers discovered traces of fire, but too slight to be worthy of more than a passing remark.

A mound marked E in the plan of the great work, Plate XXI, No. 2, was found to enclose an altar of small dimensions, which contained only a few perforated wolf’s teeth and some fifteen or twenty bones of the deer, all of them much burned. Six or eight inches above the deposit was a stratum of large pebbles.

It has been remarked that some of the mounds of this class contain altars which have been but slightly burned, and that such are destitute of remains. A few altars have been noticed, which have been much burned, but having no deposit upon them, except a thin layer of phosphate of lime, which seems to have incorporated itself with the clay of which they are composed, giving them the appearance of p159 having been plastered with mortar. Nos. 6, 9, and 18, in “Mound City,” are examples of this class. No coals or ashes were found on any of these; they appear to have been carefully cleaned out before being heaped over.

An explanation of this circumstance may probably be found in the character of

a certain class of small mounds, occurring within enclosures and in connection

with the altar mounds. In the plan of “Mound City” so often referred to are

several of these, numbered 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 21 and 23, respectively. They are

very small, the largest not exceeding three feet in height, and are destitute of altars.

In place thereof, on the original level of the earth, was found a quantity, in no case

exceeding the amount of one skeleton, of burned human bones, in small fragments.

That they were not burned on the spot is evident from the absence of all traces of

fire, beyond those furnished by the remains themselves. They appear to have

been collected from the pyre, wherever it was erected, and carefully deposited in

a small heap, and then covered over. In one instance (mound No. 19) a small

Fig. 47.

hole had been dug, in which the remains were found. A section of this mound

is herewith given, Fig. 47. The

deposit is indicated by the letter a.

This feature is analogous to the

cists of the British barrows. That

the burning took place on some of

the altars above mentioned is not only indicated by the presence of the deposit

of phosphate of lime upon them, but is absolutely demonstrated by finding, intermixed

with the calcined bones, fragments of the altars themselves, as if portions

had been scaled up by the instrument used in scraping together and removing the

burned remains.

Fig. 47.

hole had been dug, in which the remains were found. A section of this mound

is herewith given, Fig. 47. The

deposit is indicated by the letter a.

This feature is analogous to the

cists of the British barrows. That

the burning took place on some of

the altars above mentioned is not only indicated by the presence of the deposit

of phosphate of lime upon them, but is absolutely demonstrated by finding, intermixed

with the calcined bones, fragments of the altars themselves, as if portions

had been scaled up by the instrument used in scraping together and removing the

burned remains.

The inference that human sacrifices were made here, and the remains afterwards thus collected and deposited, or that a system of burial of this extraordinary character was practised in certain cases, seems to follow legitimately from the facts and circumstances here presented.103

That the stratified mounds are not burial places seems sufficiently well established by the fact that the greater number have no traces of human remains upon or around the altars. The suggestion that the various relics found upon these altars were the personal effects of deceased chiefs or priests, thus deposited in accordance with the practice common amongst rude people, of consigning the property of the dead to the tomb with them, is controverted by the fact that p160 the deposits are generally homogeneous. That is to say, instead of finding a large variety of relics, ornaments, weapons, and other articles, such as go to make up the possessions of a barbarian dignitary, we find upon one altar pipes only, upon another a simple mass of galena, while the next one has a quantity of pottery, or a collection of spear heads, or else is destitute of remains except perhaps a thin layer of carbonaceous material. Such could not possibly be the case upon the above hypothesis, for the spear, the arrows, the pipe, and the other implements and personal ornaments of the dead, would then be found in connection with each other. Besides the negative evidence here afforded in support of our classification, it is sustained by the circumstance that these mounds are almost invariably found within enclosures, which, for a variety of concurring reasons, we are induced to believe were sacred in their origin, and devoted primarily, if not exclusively, to religious purposes. The circumstance of stratification, exhibiting as it does an extraordinary care and attention, can hardly be supposed to result from any but superstitious notions. It certainly has no exact analogy in any of the monuments of the globe, of which we possess a knowledge, and its significance is beyond rational conjecture. Why these altars, some of which, as we have already seen, had been used for considerable periods, were finally heaped over, is an embarrassing question, and one to which it is impossible to suggest a satisfactory answer. That all were not covered by mounds is quite certain. The “brick hearths,” of which mention has occasionally been made by writers upon our antiquities, were doubtless none other than uncovered altars. Nothing is more likely than that, even though designed to be subsequently covered, some were left exposed by the builders, and afterwards hidden by natural accumulations, to be again exposed by the invading plough or the recession of the banks of streams. The indentations occasioned by the growth of roots over their surfaces, or the cracks resulting from other causes, would naturally suggest the notion of rude brick hearths. One of these “hearths” was discovered some years since near the town of Marietta in Ohio. It was surrounded by a low bank, of about one hundred feet in circumference, which seemed to have been the ground plan or commencement of a mound.

-

FOOTNOTES TO CHAPTER VI.

-

99 It is not assumed to say that all the mounds occurring within enclosures are altar or sacrificial mounds. On the contrary, some are found which, to say the least, are anomalous; while others were clearly the sites of structures, or temple mounds.

-

100 Some of the mounds on the lower Mississippi, as we have already seen in the chapter on the aboriginal monuments of the Southern States, are horizontally stratified, exhibiting numerous layers, from base to summit. These mounds differ in form from the conical structures here referred to, and were perhaps constructed for a different purpose. Some are represented as composed of layers of earth, two or three feet thick, each one of which is surmounted by a burned surface, which has been mistaken for a rude brick pavement. Others are composed of alternate layers of earth and human remains. The origin of the latter is doubtless to be found in the annual bone burials of the Cherokees and other southern Indians, of which accounts are given by Bartram and the early writers.

-

101 In the construction of the Ohio canal, a mound was partially excavated, in which were found a dial-plate and other articles of European origin. The circumstances are detailed in a private letter from WILLIAM H. PRICE, Esq., of Chillicothe, late member of the Board of Public Works of Ohio, under whose direction the mound was removed:

“In the year 1827, during the excavation of a part of the Ohio canal in the township of Benton, Cuyahoga county, a short distance north of the mouth of Brandywine creek, it became necessary to remove part of a small mound, so situated in the valley of a small rivulet as, at first, to induce doubts as to its being artificial. However, in the process of excavation, the remains of one or more human skeletons were found, also a gun barrel, and perhaps some of the mountings of the stock. In relation to the last I am not positive, but distinctly remember a circular brass plate or disc perhaps one sixteenth of an inch in thickness, with (I think) raised letters and figures on one side, which exhibited a French calendar, so arranged as to serve for a century. I may mistake the duration for which it was intended, but give the above as my decided impression. I do not recollect the date, but think it was near the middle of the seventeenth century,—say 1640 or thereabouts.”

Several silver crosses, a number of small bags of vermilion, and other relics, were discovered not long since by Mr. C. A. VAUGHN, of Cincinnati, in some mounds excavated by that gentleman in the vicinity of Beardstown, Ill. They were found with skeletons, a few feet below the surface.

-

102 The skull of this skeleton, which is singularly large and massive, is now in the possession of Samuel G. Morton, M.D., of Philadelphia. It is of the same conformation with those of the recent Indians which surround it in his extensive collection.

-

103 Amongst the Mexicans, burial by fire was generally practised. Clavigero mentions a fact, in connection with their funeral rites, which may serve to elucidate the point here raised, viz that burial in the vicinity of some altar or temple, or in the sacred places where sacrifices were made, was often sought by the Mexicans:

“There was no fixed place for burials. Many ordered their ashes to be buried near some temple or altar, some in the fields, and others in their sacred places in the mountains where sacrifices used to be made. The ashes of the kings and lords were, for the most part, deposited in the towers of the temples, especially those of the greater temple.”—Clavigero, American Edition, vol ii. p. 108; Acosta in Purchas, vol. iii. p. 1029.

-